Right, after running a poll victory belonged to "In Defence of the Republic", and after experimenting a bit I've decided to run this timeline with some of the elements we saw on "Sons of Neptune", although at least for the first chapters I'll refrain from writing them like a novel considering just how much is there to establish. I hope you will enjoy it!

In Defence of the Republic:

Index:

Prologue

Introduction

Dramatis Personae

A Note on Sources

Book One: Triumvirs and Liberatores

Part I: Octavianus, Divi Filius

Part II: Cassius Aegyptiacus

Part III: Brutus in Asia

Part IV: The Second Triumvirate

Part V: Sextus Pompeius Magnus

Part VI: The War of the Triumvirs

Part VII: The Pact of Neapolis

Book Two: Concordia Ordinum

Part VIII: The Consulate of Brutus and Cassius

Part IX: The Antonian Revolt (being worked on)

Part X: Cicero's Constitution (being worked on)

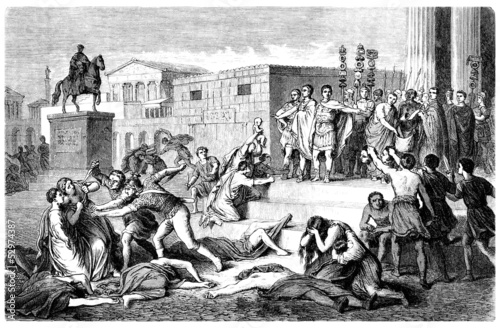

More than a year had passed since Caesar had been stabbed to death by the Senators at Pompey’s Theatre, and the specter of civil war had expanded to the whole of the Republic. The past year itself had been a monstrous doubt altogether as the Liberatores and the heirs of Caesar had fought their own political battles, and the current one had made it clear one of them would necessarily have to prevail by military force. Some had hoped for an arrangement, for Rome to continue its life without restoring to another war… and such hopes were over.

The Liberatores were struck the first blows, fleeing Rome as some of their more capable Generals fell one by one: Gaius Trebonius as the treasonous hands of Dolabella, Lucius Minucius Basilus killed by his own slaves, and Decimus Brutus killed while fleeing a desperate situation in the Cisalpine Gaul. The war had forced endless changes of positions between those who had stayed in the west, as Cicero tried to steer the Senate as an independent force once again and Lepidus, Plancus, Antonius and the unexpected force Octavian had proved to be fought each other in a seemingly endless cat and mouse. To the shock of many, what should have been a monstrous battle turned into the most unlikely of arrangements, for Lepidus, Octavian and Antonius had joined forces as the new Triumvirs, marching on Rome to correct a Senate which had proved too independent.

The west left to the heirs of Caesar, the Liberatores split across the East and step by step their power grew. Gaius Cassius, left as the best of their generals on account of Trebonius and Decimus’s deaths, led the fight against Dolabella in Syria, not only being hailed as Imperator as he utterly defeated his rival, but also amassing a fearsome fighting force. Marcus Brutus, never the man of action others were, would also amass his own power as Macedonia, Asia, Achaea and Bithynia would slowly fall to his lieutenants. If that was to be added to the fleets of the great naval renegades Ahenobarbus and Sextus Pompeius, it was a fearsome war machine not to be underestimated, far stronger than anything the Optimates had put in place against Caesar.

In the timeline we know as our history Cicero would be killed as the Triumvirs instituted proscription across Rome, and Cassius would return early to join Brutus at his request, forcing a tense campaign that would end in Philippi as the Liberatores were crushed and dozens of Rome’s most influent aristocrats met their end. It would be a victory that would eventually fall under the propaganda of that most ruthless of Caesar’s heirs, the future Caesar Augustus; victor over his colleagues in the Triumvirate. But what if? What if, in a different scenario, Cicero was to escape this bloody proscription? What if Brutus had assessed the situation differently and not called for Cassius too early? What if, as Octavian would always insist, Lepidus had been messaging Sextus Pompeius to craft a backup plan of his own?

What would have been of the Roman Republic on this different world?

Liberatores:

Gaius Cassius Longinus

The energetic general who saved the day after Carrhae, one of the heads behind the Ides of March and current master of Syria after his triumph over Dolabella.

Marcus Junius Brutus

Far more of a political man than Cassius, currently the richest man in Rome and sole heir to the Junii Bruti and the Servili Caepionis, slowly gaining control over the East.

Sextus Pompeius Magnus Pius

The “Son of Neptune”, Pompey Magnus’s surviving son and unparalleled admiral, his fleets control Sicily and Sardinia and gives Pompeius full power over the grain supply.

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Pater Patriae, the man who saved the Republic from Catiline only to go through a humiliation conga thanks to Clodius, Curio, Caesar, Pompeius, and company. Now trying to destroy Antonius by manipulating the Senate.

Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus

Noblest of his family according to Suetonius and son of one of Caesar’s most bitter enemies, about to be made admiral of Brutus’s fleets to try his luck on the sea.

Caesarians:

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

OTL Triumvir, Lepidus’s own role has been less important that many would have expected after the Ides of March, but the war is young and killing the man would be sacrilege as he is Pontifex Maximus.

Lucius Munatius Plancus

Our OTL would deem him Ancient Talleyrand, as Plancus, formerly a loyal legate of Caesar, would change his allegiances towards Cicero and the Senate, then to Decimus Brutus, then to Lepidus, and now to Antony. Will he change sides yet again?

Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus

Current master of Rome after outmaneuvering Antony and the Senate, Octavianus has proved to be obsessed with avenging Caesar, as he is now his legal heir.

Marcus Antonius

OTL Triumvir, he has seen defeat and victory embrace him and change sides far too many times since the last year, but he’s still going strong and has a massive army.

Lucius Antonius

Antonius's brother, experience politician and a passable demagogue aiming to aid his brother on his quest for power. Tends to be controlled by Fulvia, his brother's wife.

[FONT="]

[/FONT]

One of the advantages one has about writing on this period is the large amount sources one can use, although the loss that represents the death of Cicero is a noticeable one. In that sense, I’ve tried to keep a balance with the use of classical sources and modern studies in order to craft my interpretation of the facts. Mind you, a lot of what happened during this period of time is open to a certain degree of interpretation, so it is perfectly possible that some might disagree with my approach. That said I’ve tried to keep it as realistic as I possibly can with limited knowledge.

My classical sources will heavy borrow from Cassius Dio, with a lot of effort put as well on Appian, Veleius Paterculus and, of course, Plutarch. Cicero’s correspondence has also been helpful in many aspects, just like his fiery speeches against Mark Antony. Suetonius also came in handy for aspects of Caesar and Octavianus, but personally I’m not a fan of his. Regarding modern sources I’ve used Ludwig, Wertheimer and Fletcher’s biographies for Cleopatra, Weigel’s biography for Lepidus, Seager’s biography for Pompeius Magnus and Rogers and Syme’s studies for Sextus Pompey and the Pompeians in general (along with several Spanish studies on the Pompeian influence in Hispania), Goltz Huzar’s Mark Antony’s biography, and for certain issues Kelly’s History of Exile in the Roman Republic, Gruen’s The Last Generation of the Roman Republic, Wiseman’s New Men in the Roman Senate and David Rafferty’s studies on the Princeps Senatus.

In terms of references and info, my limited knowledge on roman officeholders comes from Broughton’s brilliant The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, the chronology is often sustained by Venning’s A Chronology of the Roman Empire, and the finer details of some of the minor characters are sustained by the venerable William Smith´s Dictionary of Roman and Greek Biography. All in all, the sheer scope of characters and wildcards one can find can be very daunting, and in keeping track of dates and people I am bound to make mistakes. Please do let me know if something looks implausible or is incorrect!

Prologue

Introduction

Dramatis Personae

A Note on Sources

Book One: Triumvirs and Liberatores

Part I: Octavianus, Divi Filius

Part II: Cassius Aegyptiacus

Part III: Brutus in Asia

Part IV: The Second Triumvirate

Part V: Sextus Pompeius Magnus

Part VI: The War of the Triumvirs

Part VII: The Pact of Neapolis

Book Two: Concordia Ordinum

Part VIII: The Consulate of Brutus and Cassius

Part IX: The Antonian Revolt (being worked on)

Part X: Cicero's Constitution (being worked on)

Prologue:

Introduction:

Introduction:

Gaius Julius Caesar, now a Roman God

[FONT="]…[/FONT]

[FONT="]

Across the Roman Republic, 43 BC / 711 AUC:

[/FONT]

Across the Roman Republic, 43 BC / 711 AUC:

[/FONT]

The Liberatores were struck the first blows, fleeing Rome as some of their more capable Generals fell one by one: Gaius Trebonius as the treasonous hands of Dolabella, Lucius Minucius Basilus killed by his own slaves, and Decimus Brutus killed while fleeing a desperate situation in the Cisalpine Gaul. The war had forced endless changes of positions between those who had stayed in the west, as Cicero tried to steer the Senate as an independent force once again and Lepidus, Plancus, Antonius and the unexpected force Octavian had proved to be fought each other in a seemingly endless cat and mouse. To the shock of many, what should have been a monstrous battle turned into the most unlikely of arrangements, for Lepidus, Octavian and Antonius had joined forces as the new Triumvirs, marching on Rome to correct a Senate which had proved too independent.

The west left to the heirs of Caesar, the Liberatores split across the East and step by step their power grew. Gaius Cassius, left as the best of their generals on account of Trebonius and Decimus’s deaths, led the fight against Dolabella in Syria, not only being hailed as Imperator as he utterly defeated his rival, but also amassing a fearsome fighting force. Marcus Brutus, never the man of action others were, would also amass his own power as Macedonia, Asia, Achaea and Bithynia would slowly fall to his lieutenants. If that was to be added to the fleets of the great naval renegades Ahenobarbus and Sextus Pompeius, it was a fearsome war machine not to be underestimated, far stronger than anything the Optimates had put in place against Caesar.

In the timeline we know as our history Cicero would be killed as the Triumvirs instituted proscription across Rome, and Cassius would return early to join Brutus at his request, forcing a tense campaign that would end in Philippi as the Liberatores were crushed and dozens of Rome’s most influent aristocrats met their end. It would be a victory that would eventually fall under the propaganda of that most ruthless of Caesar’s heirs, the future Caesar Augustus; victor over his colleagues in the Triumvirate. But what if? What if, in a different scenario, Cicero was to escape this bloody proscription? What if Brutus had assessed the situation differently and not called for Cassius too early? What if, as Octavian would always insist, Lepidus had been messaging Sextus Pompeius to craft a backup plan of his own?

What would have been of the Roman Republic on this different world?

Dramatis Personae:

Liberatores:

Gaius Cassius Longinus

The energetic general who saved the day after Carrhae, one of the heads behind the Ides of March and current master of Syria after his triumph over Dolabella.

Marcus Junius Brutus

Far more of a political man than Cassius, currently the richest man in Rome and sole heir to the Junii Bruti and the Servili Caepionis, slowly gaining control over the East.

Sextus Pompeius Magnus Pius

The “Son of Neptune”, Pompey Magnus’s surviving son and unparalleled admiral, his fleets control Sicily and Sardinia and gives Pompeius full power over the grain supply.

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Pater Patriae, the man who saved the Republic from Catiline only to go through a humiliation conga thanks to Clodius, Curio, Caesar, Pompeius, and company. Now trying to destroy Antonius by manipulating the Senate.

Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus

Noblest of his family according to Suetonius and son of one of Caesar’s most bitter enemies, about to be made admiral of Brutus’s fleets to try his luck on the sea.

Caesarians:

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

OTL Triumvir, Lepidus’s own role has been less important that many would have expected after the Ides of March, but the war is young and killing the man would be sacrilege as he is Pontifex Maximus.

Lucius Munatius Plancus

Our OTL would deem him Ancient Talleyrand, as Plancus, formerly a loyal legate of Caesar, would change his allegiances towards Cicero and the Senate, then to Decimus Brutus, then to Lepidus, and now to Antony. Will he change sides yet again?

Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus

Current master of Rome after outmaneuvering Antony and the Senate, Octavianus has proved to be obsessed with avenging Caesar, as he is now his legal heir.

Marcus Antonius

OTL Triumvir, he has seen defeat and victory embrace him and change sides far too many times since the last year, but he’s still going strong and has a massive army.

Lucius Antonius

Antonius's brother, experience politician and a passable demagogue aiming to aid his brother on his quest for power. Tends to be controlled by Fulvia, his brother's wife.

[FONT="]

[/FONT]

A Note on Sources:

My classical sources will heavy borrow from Cassius Dio, with a lot of effort put as well on Appian, Veleius Paterculus and, of course, Plutarch. Cicero’s correspondence has also been helpful in many aspects, just like his fiery speeches against Mark Antony. Suetonius also came in handy for aspects of Caesar and Octavianus, but personally I’m not a fan of his. Regarding modern sources I’ve used Ludwig, Wertheimer and Fletcher’s biographies for Cleopatra, Weigel’s biography for Lepidus, Seager’s biography for Pompeius Magnus and Rogers and Syme’s studies for Sextus Pompey and the Pompeians in general (along with several Spanish studies on the Pompeian influence in Hispania), Goltz Huzar’s Mark Antony’s biography, and for certain issues Kelly’s History of Exile in the Roman Republic, Gruen’s The Last Generation of the Roman Republic, Wiseman’s New Men in the Roman Senate and David Rafferty’s studies on the Princeps Senatus.

In terms of references and info, my limited knowledge on roman officeholders comes from Broughton’s brilliant The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, the chronology is often sustained by Venning’s A Chronology of the Roman Empire, and the finer details of some of the minor characters are sustained by the venerable William Smith´s Dictionary of Roman and Greek Biography. All in all, the sheer scope of characters and wildcards one can find can be very daunting, and in keeping track of dates and people I am bound to make mistakes. Please do let me know if something looks implausible or is incorrect!

Last edited: