16.Egypt during the late 320’s

I, Usermontu, iry-pat, Royal Companion, Fan-bearer on the Right Side of the King, Admiral of the Fleet of Upper Egypt, priest of Horus at his temple at Djeba, was alongside the younger god when he waged war against vile Kush. His Majesty praised me for my valour and strength, and awarded me with estates in Nubia and made me Overseer of the Lands of Kush. He ordered me to restore the fortress at Semna and the shrines located therein. This I did for His Majesty, I reinforced the walls and towers, and I renamed the fortress ‘Khakaura-smites-the-Kushites’.

- Inscription of Usermontu found at Semna

Nakhtnebef’s second campaign against the Nubians was a great victory for the Lord of the Two Lands. His and his father’s earlier campaigns to the south had prepared the way for the eventual annexation of large tracts of land. The pharaoh’s motivation for annexing the lands up to the Fourth Cataract were not much different from his distant predecessors, controlling the trade and the gold mines plus eliminating a potential threat was more than enough reason for an ambitious ruler. The king returned to Memphis in April 324 and seems to have spend the rest of the year in Lower Egypt. Construction projects around this time were concentrated in the Delta, at the Iseion [1] at Hebyt he ordered extensive expansions, a new pylon and courtyard were to be constructed, which would include shrines to Isis herself, her husband Osiris and two forms of the god Horus. These were Hor-pa-Khered (Horus-the-Child), a child form of the falcon deity which was associated with healing, and a new form of the god, Hor-Nakht (Horus the Victor), associated with military victory. Probably a theological invention of the king himself or one of his close advisors, Hor-Nakht associated the king even more explicitly with martial glory, and is often portrayed holding either a mace or spear, striking at Egypt’s enemies. He was closely associated with the Thirtieth Dynasty, but later on would become more or less the patron of the army, together with Montu and Anhur.

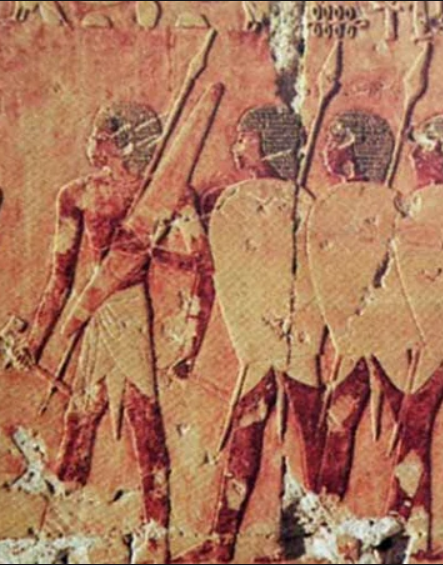

It is around this time, after the Second Nubian Campaign, that the king started his military reforms. Egypt’s military was built on two pillars: the native machimoi and the foreign mercenaries, mostly Greek but substantial amounts of Phoenicians, Judeans and Arabs also served, in addition to the Nubians and Libyans. The sometimes strained relationship between the Delta nobility, who commanded the machimoi, and the monarchy, had caused clashes in the past and had notably led to the end of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty and the Achaemenid conquest of Egypt. The recent capture of the gold mines of Nubia, and the plunder from his campaigns, were a significant addition to the pharaonic treasury. Now in addition to his mercenary forces Nakhtnebef raised several regiments of Egyptian professional troops, who would serve directly beneath the king. They were named the senenu, ‘companions’, which betrays where the king got his idea from. Philip II had used the gold of Pangaion to forge the Macedonians into an world-conquering army, now Nakhtnebef II would use the gold of Nubia to establish an professional army of his own. Despite this inspiration they were not armed like the Macedonians, the Egyptians would for now not adapt the pike phalanx. Like the machimoi the senenu were a versatile force, often armed with a large shield, a spear, polearm or axe, their armour consisting of leather, linen or in some cases bronze or iron scales. In contrast to the machimoi however most of the senenu were equipped with bronze helmets. The Macedonian influence is more apparent with the cavalry, part of which the king had reorganised as Macedonian-style lancers, and employed both Egyptians and foreigners among their ranks. They were already in place before the Nubian campaign, and played an important part in the decisive battle at Kawa. Bakenanhur, close confidante and friend of the king, was given the title ‘commander of the horsemen’ and was thus in charge of the cavalry regiments of the senenu.

In this era, despite Nakhtnebef’s investments, the senenu would never compose more than a fifth of the Egyptian army, still outnumbered by the machimoi and the mercenaries. It did however provide the king with a loyal force, and a counterbalance to the Delta nobility and their machimoi. Unsurprisingly the most of the senenu were stationed at Memphis, from where they could move quickly either into the Delta, into Asia or upriver to Upper Egypt and beyond. Some were also garrisoned in Sidon, Damascus or Gaza, and others in the Nubian fortresses or at the kingdom’s new southern border at Napata. They would be supplied from royal granaries, and their families would be provided for by the state. Most of the senenu were drawn from the machimoi, who gave up their plot of land in the Delta and decided to fully dedicate themselves to warfare.

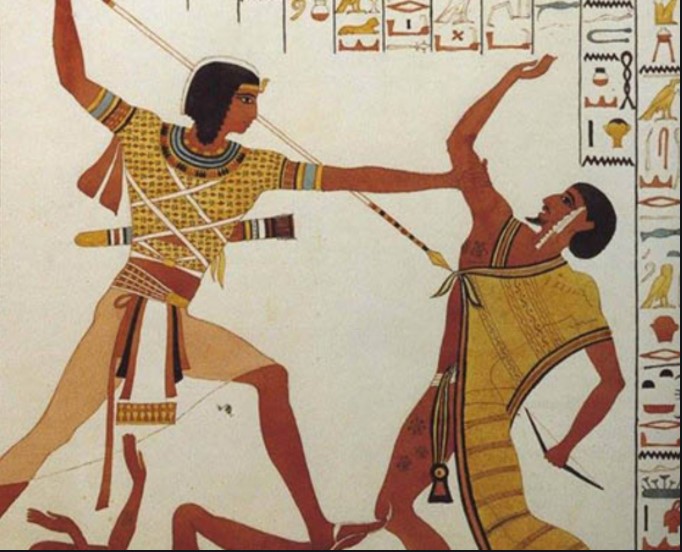

Egyptian soldier attacking a Libyan tribesman

Despite the prominence of this military project the years between 324 and 320 were mostly peaceful for Egypt. The king’s focus during these years was on his building projects, most notably his additions to his father’s festival complex just north of Memphis [2]. The already existing shrines of Amun and Ra were enlarged, two obelisks were erected on the riverside, proclaiming the piety of Nakhtnebef as king and his dedication to his father. The festival hall, where his father had celebrated the Sed-festival, was also expanded with a forecourt which included a sacred lake dedicated to Osiris. Near the end of Nakhtnebef’s reign a start was also made on the enclosure wall which eventually surrounded the temple complex, but it would only be completed under his successor. On one of the obelisks on the riverside the king gives his reasoning for the building project: ‘Here I made a home for my father Amun-Ra, King of the Gods, a northern sanctuary for the Royal Ka’. It was this name, Northern Sanctuary, or Ipet-Mehu, which would become the name under which the complex was known.

Outside of his construction works at Hebyt and Ipet-Mehu it was mostly at Waset that Nakhtnebef focussed his efforts. Major reconstruction work was done at Ipet-Resyt [3], where Nakhtnebef restored the works of his distant predecessors but also made sure that his own name was recorded among the inscriptions. At Ipetsut he unceremoniously had the barque-shrine [4] of Hakor, which was located just outside the First Pylon, dismantled and a new one constructed. The respect that Nakhtnebef showed to his distant predecessors of the New Kingdom he did not grant to the Twenty-Ninth Dynasty ruler. His most remarkable construction was the processional road he ordered, which led from the left bank of the Nile to the Djeser-Djeseru [5] in the hills west of Waset, and the small mortuary chapel he constructed near the west bank of the Nile.

The Thirtieth Dynasty had reinvigorated many traditions from the distant past, eager as they were to portray themselves as the rightful heirs of the now legendary kings of the New Kingdom, and Nakhtnebef II was no exception. For the first time in centuries a pharaonic funerary monument would arise on the western bank near Waset. While its size did not compare to the vast edifices constructed by the Ramessides the mortuary chapel of Nakhtnebef II was intricately decorated, both on the inside and the outside. On the outside Nakhtnebef is portrayed as the very image of a warrior-king, showing him in battle and crushing his enemies. On the inside of the temple the scenes are more private, Nakhtnebef is portrayed in leisure among his family, seated besides his wife while the royal children are playing. Remarkably intimate scenes, showing that besides a warrior the king was also a family man. In the temple’s inner sanctum, where the king’s cult statue would be kept, he is portrayed among the gods, who clasp him by the shoulder as if greeting a long lost friend. The chapel was located near the edge of the floodplain and near a quay, which gave it a unique position in another tradition which Nakhtnebef reinvigorated. During the Beautiful Festival of the Valley the cult statues of Amun-Ra, Mut and Khonsu would be taken out of Ipetsut and would visit the mortuary temples in the west of Waset. The height of the Festival’s splendour had been during the New Kingdom, but it had somewhat diminished during later periods, now however with a royal sponsor interested in the traditions of Waset and an abundance of Nubian gold the festival was once again one of the most important of the land [6]. With his mortuary temple located on the riverbank it was the first one to be visited by the gods during their journey to the Djeser-Djeseru, a great honour for the king, but also quite fitting for a man who had done so much to restore the prominence of the southern city.

The political situation of the Egyptian Kingdom was, thanks to increased prosperity, manageable for the king. Aided by his capable vizier Ankhefenkhonsu Nakhtnebef was generally seen as a capable, if somewhat military-centric ruler. The increased income from trade and the Nubian gold mines even allowed the ruler to alleviate the taxes on both the commoners and the temple estates, enhancing the popularity of the king. Nubia was ruled harshly in those days, and required a constant military presence. In contrast the Near Eastern ‘empire’ was more or less autonomous, safeguarded by several garrisons Egyptian rule more or less amounted to benign neglect. As long as tribute and trade flowed from the Levant into Egypt there was no reason for intervention. On the diplomatic front the most important event was the visit of Hieronymos of Cardia, envoy of Alexander, to Nakhtnebef. The pharaoh met him at the fortress of Pelusium. With the impressive battlements of the great fortress as background, Nakhtnebef hoped to make an impression on the foreigners who now visited Egypt. Stories of Alexander’s great eastern conquest had off course reached the land of the Nile, and Nakhtnebef, though a proud ruler who fancied himself a great warrior, must have thought it better not to provoke the conqueror. Thankfully for Nakhtnebef Alexander was, at least for now, not in a warlike mood. He had an empire to run, and needed at least several years to consolidate his gains. Egypt, with its control over valuable trade routes and bountiful natural resources, must have been an alluring target for the Great King, but for now its conquest was not on his agenda. The alliance between the Argeads and Egypt, once settled by Nakhthorheb and Philip, was now renewed by their sons, and gifts were exchanged. To a lesser ruler the king of Egypt would have sent gold, but since Alexander was one of the few who could say he was richer than the pharaoh that wasn’t an option. Indeed, Hieronymos gave Nakhtnebef precious lapis-lazuli and other exotic goods (apparently even an Indian brahman), and in return received something that Egyptian kings were always loathe to part with. Hieronymos returned to Babylon with a daughter of the pharaoh, although not by his primary wife, a 20-year old named Nitiqret (‘Neith is excellent’) whom the Macedonians would name Nitokris. For the pharaoh parting with one of his daughters was a rare humiliation, but a necessary one if he wished to keep relations with his much more powerful neighbour peaceful. In that way the marriage of Nitokris to Alexander could certainly be seen as a victory.

Footnotes

I, Usermontu, iry-pat, Royal Companion, Fan-bearer on the Right Side of the King, Admiral of the Fleet of Upper Egypt, priest of Horus at his temple at Djeba, was alongside the younger god when he waged war against vile Kush. His Majesty praised me for my valour and strength, and awarded me with estates in Nubia and made me Overseer of the Lands of Kush. He ordered me to restore the fortress at Semna and the shrines located therein. This I did for His Majesty, I reinforced the walls and towers, and I renamed the fortress ‘Khakaura-smites-the-Kushites’.

- Inscription of Usermontu found at Semna

Nakhtnebef’s second campaign against the Nubians was a great victory for the Lord of the Two Lands. His and his father’s earlier campaigns to the south had prepared the way for the eventual annexation of large tracts of land. The pharaoh’s motivation for annexing the lands up to the Fourth Cataract were not much different from his distant predecessors, controlling the trade and the gold mines plus eliminating a potential threat was more than enough reason for an ambitious ruler. The king returned to Memphis in April 324 and seems to have spend the rest of the year in Lower Egypt. Construction projects around this time were concentrated in the Delta, at the Iseion [1] at Hebyt he ordered extensive expansions, a new pylon and courtyard were to be constructed, which would include shrines to Isis herself, her husband Osiris and two forms of the god Horus. These were Hor-pa-Khered (Horus-the-Child), a child form of the falcon deity which was associated with healing, and a new form of the god, Hor-Nakht (Horus the Victor), associated with military victory. Probably a theological invention of the king himself or one of his close advisors, Hor-Nakht associated the king even more explicitly with martial glory, and is often portrayed holding either a mace or spear, striking at Egypt’s enemies. He was closely associated with the Thirtieth Dynasty, but later on would become more or less the patron of the army, together with Montu and Anhur.

It is around this time, after the Second Nubian Campaign, that the king started his military reforms. Egypt’s military was built on two pillars: the native machimoi and the foreign mercenaries, mostly Greek but substantial amounts of Phoenicians, Judeans and Arabs also served, in addition to the Nubians and Libyans. The sometimes strained relationship between the Delta nobility, who commanded the machimoi, and the monarchy, had caused clashes in the past and had notably led to the end of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty and the Achaemenid conquest of Egypt. The recent capture of the gold mines of Nubia, and the plunder from his campaigns, were a significant addition to the pharaonic treasury. Now in addition to his mercenary forces Nakhtnebef raised several regiments of Egyptian professional troops, who would serve directly beneath the king. They were named the senenu, ‘companions’, which betrays where the king got his idea from. Philip II had used the gold of Pangaion to forge the Macedonians into an world-conquering army, now Nakhtnebef II would use the gold of Nubia to establish an professional army of his own. Despite this inspiration they were not armed like the Macedonians, the Egyptians would for now not adapt the pike phalanx. Like the machimoi the senenu were a versatile force, often armed with a large shield, a spear, polearm or axe, their armour consisting of leather, linen or in some cases bronze or iron scales. In contrast to the machimoi however most of the senenu were equipped with bronze helmets. The Macedonian influence is more apparent with the cavalry, part of which the king had reorganised as Macedonian-style lancers, and employed both Egyptians and foreigners among their ranks. They were already in place before the Nubian campaign, and played an important part in the decisive battle at Kawa. Bakenanhur, close confidante and friend of the king, was given the title ‘commander of the horsemen’ and was thus in charge of the cavalry regiments of the senenu.

In this era, despite Nakhtnebef’s investments, the senenu would never compose more than a fifth of the Egyptian army, still outnumbered by the machimoi and the mercenaries. It did however provide the king with a loyal force, and a counterbalance to the Delta nobility and their machimoi. Unsurprisingly the most of the senenu were stationed at Memphis, from where they could move quickly either into the Delta, into Asia or upriver to Upper Egypt and beyond. Some were also garrisoned in Sidon, Damascus or Gaza, and others in the Nubian fortresses or at the kingdom’s new southern border at Napata. They would be supplied from royal granaries, and their families would be provided for by the state. Most of the senenu were drawn from the machimoi, who gave up their plot of land in the Delta and decided to fully dedicate themselves to warfare.

Egyptian soldier attacking a Libyan tribesman

Despite the prominence of this military project the years between 324 and 320 were mostly peaceful for Egypt. The king’s focus during these years was on his building projects, most notably his additions to his father’s festival complex just north of Memphis [2]. The already existing shrines of Amun and Ra were enlarged, two obelisks were erected on the riverside, proclaiming the piety of Nakhtnebef as king and his dedication to his father. The festival hall, where his father had celebrated the Sed-festival, was also expanded with a forecourt which included a sacred lake dedicated to Osiris. Near the end of Nakhtnebef’s reign a start was also made on the enclosure wall which eventually surrounded the temple complex, but it would only be completed under his successor. On one of the obelisks on the riverside the king gives his reasoning for the building project: ‘Here I made a home for my father Amun-Ra, King of the Gods, a northern sanctuary for the Royal Ka’. It was this name, Northern Sanctuary, or Ipet-Mehu, which would become the name under which the complex was known.

Outside of his construction works at Hebyt and Ipet-Mehu it was mostly at Waset that Nakhtnebef focussed his efforts. Major reconstruction work was done at Ipet-Resyt [3], where Nakhtnebef restored the works of his distant predecessors but also made sure that his own name was recorded among the inscriptions. At Ipetsut he unceremoniously had the barque-shrine [4] of Hakor, which was located just outside the First Pylon, dismantled and a new one constructed. The respect that Nakhtnebef showed to his distant predecessors of the New Kingdom he did not grant to the Twenty-Ninth Dynasty ruler. His most remarkable construction was the processional road he ordered, which led from the left bank of the Nile to the Djeser-Djeseru [5] in the hills west of Waset, and the small mortuary chapel he constructed near the west bank of the Nile.

The Thirtieth Dynasty had reinvigorated many traditions from the distant past, eager as they were to portray themselves as the rightful heirs of the now legendary kings of the New Kingdom, and Nakhtnebef II was no exception. For the first time in centuries a pharaonic funerary monument would arise on the western bank near Waset. While its size did not compare to the vast edifices constructed by the Ramessides the mortuary chapel of Nakhtnebef II was intricately decorated, both on the inside and the outside. On the outside Nakhtnebef is portrayed as the very image of a warrior-king, showing him in battle and crushing his enemies. On the inside of the temple the scenes are more private, Nakhtnebef is portrayed in leisure among his family, seated besides his wife while the royal children are playing. Remarkably intimate scenes, showing that besides a warrior the king was also a family man. In the temple’s inner sanctum, where the king’s cult statue would be kept, he is portrayed among the gods, who clasp him by the shoulder as if greeting a long lost friend. The chapel was located near the edge of the floodplain and near a quay, which gave it a unique position in another tradition which Nakhtnebef reinvigorated. During the Beautiful Festival of the Valley the cult statues of Amun-Ra, Mut and Khonsu would be taken out of Ipetsut and would visit the mortuary temples in the west of Waset. The height of the Festival’s splendour had been during the New Kingdom, but it had somewhat diminished during later periods, now however with a royal sponsor interested in the traditions of Waset and an abundance of Nubian gold the festival was once again one of the most important of the land [6]. With his mortuary temple located on the riverbank it was the first one to be visited by the gods during their journey to the Djeser-Djeseru, a great honour for the king, but also quite fitting for a man who had done so much to restore the prominence of the southern city.

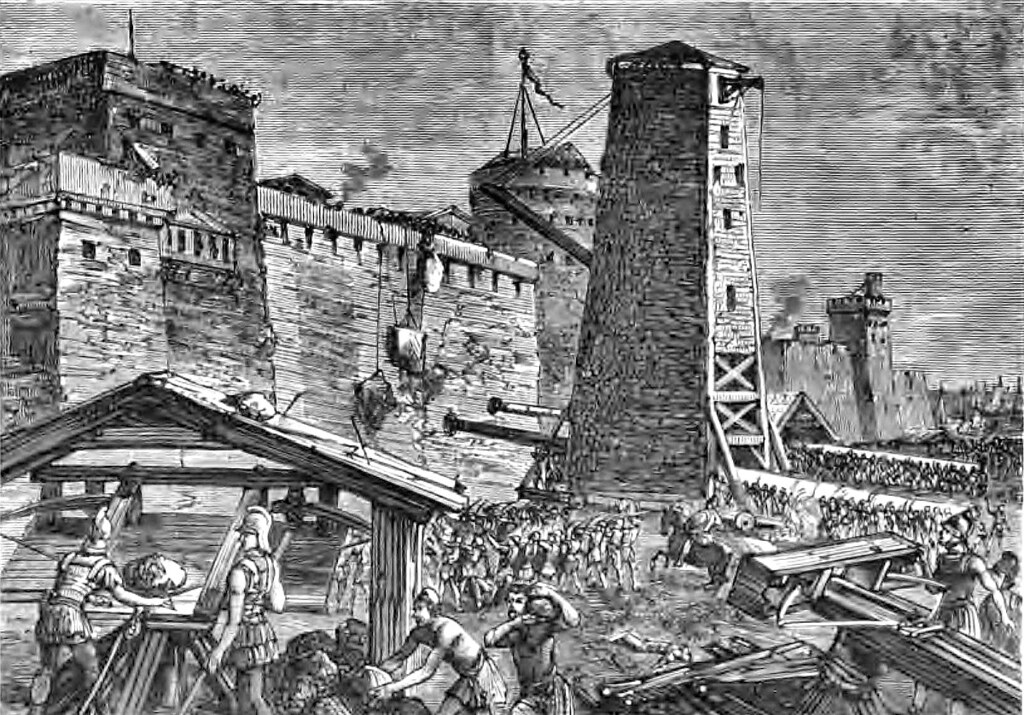

The political situation of the Egyptian Kingdom was, thanks to increased prosperity, manageable for the king. Aided by his capable vizier Ankhefenkhonsu Nakhtnebef was generally seen as a capable, if somewhat military-centric ruler. The increased income from trade and the Nubian gold mines even allowed the ruler to alleviate the taxes on both the commoners and the temple estates, enhancing the popularity of the king. Nubia was ruled harshly in those days, and required a constant military presence. In contrast the Near Eastern ‘empire’ was more or less autonomous, safeguarded by several garrisons Egyptian rule more or less amounted to benign neglect. As long as tribute and trade flowed from the Levant into Egypt there was no reason for intervention. On the diplomatic front the most important event was the visit of Hieronymos of Cardia, envoy of Alexander, to Nakhtnebef. The pharaoh met him at the fortress of Pelusium. With the impressive battlements of the great fortress as background, Nakhtnebef hoped to make an impression on the foreigners who now visited Egypt. Stories of Alexander’s great eastern conquest had off course reached the land of the Nile, and Nakhtnebef, though a proud ruler who fancied himself a great warrior, must have thought it better not to provoke the conqueror. Thankfully for Nakhtnebef Alexander was, at least for now, not in a warlike mood. He had an empire to run, and needed at least several years to consolidate his gains. Egypt, with its control over valuable trade routes and bountiful natural resources, must have been an alluring target for the Great King, but for now its conquest was not on his agenda. The alliance between the Argeads and Egypt, once settled by Nakhthorheb and Philip, was now renewed by their sons, and gifts were exchanged. To a lesser ruler the king of Egypt would have sent gold, but since Alexander was one of the few who could say he was richer than the pharaoh that wasn’t an option. Indeed, Hieronymos gave Nakhtnebef precious lapis-lazuli and other exotic goods (apparently even an Indian brahman), and in return received something that Egyptian kings were always loathe to part with. Hieronymos returned to Babylon with a daughter of the pharaoh, although not by his primary wife, a 20-year old named Nitiqret (‘Neith is excellent’) whom the Macedonians would name Nitokris. For the pharaoh parting with one of his daughters was a rare humiliation, but a necessary one if he wished to keep relations with his much more powerful neighbour peaceful. In that way the marriage of Nitokris to Alexander could certainly be seen as a victory.

Footnotes

- Temple of Isis at Hebyt

- See update 9, it’s the complex where Nakhthorheb celebrated the Sed-festival

- ‘the Southern Sanctuary’ i.e. Luxor Temple

- A barque shrine is a shrine where a sacred barque, a boat which carried a statue of a god, is kept. Karnak had multiple barque shrines, and during processions the barque would visit the shrines and rest there for some time, thus serving as waystation.

- ‘Holy of Holies’, better known as the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir al-Bahri

- OTL there isn’t much known about the Beautiful Festival of the Valley after the New Kingdom, but it is mentioned as late as the rule of emperor Augustus.

Last edited: