I do have some plans for Adea/Eurydice but I didn't plan for any additional children for Cynane and Amyntas.No way they will happen in this scenario.

Exactly as I guessed. I am wondering what happened to Cynane and Amyntas’ children? In OTL they had only a daughter but here they were married much longer than OTL

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Horus Triumphant - an Alternate Antiquity timeline

- Thread starter phoenix101

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 97 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

72. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 1 73. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 2 74. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 3 Interlude: Argead rule in Asia Interlude VII 75. Strong are the Manifestations of the Ka of Ra 76. Intrigue in Eupatoria 77. The early 220's around the AegeanLoving the TL.

I would assume Roman elites would find a good reason to want to expand their control into the Campanian region, especially with Epirote influence and beating of the Samnites and Lucani.

I'm sure they would notice that there is a new player in Magna Graecia and the Adriatic. Definitely huge butterflies.

I would assume Roman elites would find a good reason to want to expand their control into the Campanian region, especially with Epirote influence and beating of the Samnites and Lucani.

I'm sure they would notice that there is a new player in Magna Graecia and the Adriatic. Definitely huge butterflies.

Loving the TL.

I would assume Roman elites would find a good reason to want to expand their control into the Campanian region, especially with Epirote influence and beating of the Samnites and Lucani.

I'm sure they would notice that there is a new player in Magna Graecia and the Adriatic. Definitely huge butterflies.

Thank you! Well the Epirote presence for now is just a garrison in Tarentum, and while the Samnites were beaten they are far from defeated. While aware of the defeat of the Samnites the Romans also know that the Epirotes have mostly retreated. Depending on the outcome of future struggles in Italy the city-states of Magna Graecia/Megale Hellas might call for aid again. There is also of course the situation in Sicily, which I'll have to give attention to in a future update.

12. Marching east

12. Marching east

In year 2 of the 113th Olympiad, in the month of Hekatombaion, the people of this city dedicated this shrine to Zeus for the safety, well-being and glory of the Great King Alexander, King of the Macedonians, Persians, Babylonians and all the peoples of Asia, Hegemon of the Hellenic League.

- Inscription at a shrine of Zeus at Nikopolis (OTL Mosul)

In June 327 Alexander reached the city of Arbela in northern Mesopotamia, where Parmenion had already gathered reinforcements for the king. His march east from Gordion had gone without incident, but once he arrived at Arbela he received news from further east. An advance force had already been send east, as requested by Alexander, under the joint command of Lysimachos and Aristonous. In March 10000 men had set out from Ecbatana under their command, marching east to confront the rebels, who had by now gathered their forces at Hekatompylos [1]. The army there was under the command of the satrap of Parthia and Hyrcania, Phrataphernes, and consisted mostly of local infantry (many recruited from the hill tribes of Hyrcania), cavalry (both local and from the steppes) and even some Greek hoplites, mercenaries that had fled east after the battle of Mepsila. Phrataphernes probably outnumbered his opponents, but not by much. Satibarzanes and ‘Artaxerxes IV’ remained in Baktra, where they were gathering a larger army for the reconquest of Persia and Mesopotamia. They had managed to destroy Balakros’ force and kill the general himself in a surprise attack in one of the many valleys of Bactria, but a war against Alexander himself would require more preparations.

Aristonous and Lysimachos were meant to assess the situation and, if possible, delay the enemy advance. Their army largely consisted of fresh recruits, few light troops to guard the flanks and not much cavalry. Reports send to the generals by spies however indicated that Phrataphernes’ army was not large, and conquering Hekatompylos would give the Macedonians an excellent base for campaigns further east. Sensing an opportunity to score a great victory Aristonous urged action, and Lysimachos acquiesced, the army marched thus marched on Hekatompylos. During their march they were almost continually harassed by Phrataphernes’ light cavalry, and the Macedonian light cavalry was ambushed while trying to drive them away. Despite these setbacks the generals decided to push on, and reached Hekatompylos in May, and to their surprise just outside the city they were confronted with the army of Phrataphernes. Because of Macedonian dominance in the open field they had expected that Phrataphernes would let it come to a siege or that he would retreat. Eager as they were the Macedonians formed up their formation and advanced on the Hyrcanian positions, the phalanx advanced while the heavy cavalry attempted to outflank the Hyrcanians. A charge of Phrataphernes’ cavalry forced the Macedonian cavalry to retreat to guard the phalanx, and they came increasingly under fire from Phrataphernes’ light cavalry, which consisted mainly of horse archers from the steppes, mostly supplied by the Dahae, and Iranian cavalry armed with javelins and axes. The Hyrcanian infantry had fallen back, but now struck the flanks of the phalanx while the Greek mercenaries managed to hold back the centre. Often armed with a bundle of javelins and an axe they managed to hack their way into the phalanx, whose long pikes were of no use in a close-hand melee. Many of the phalangites dropped their pikes and drew their swords, but that lead to less pressure against the Greek mercenaries in the centre, who were now no longer being driven back and instead managed to put pressure on the phalanx itself.

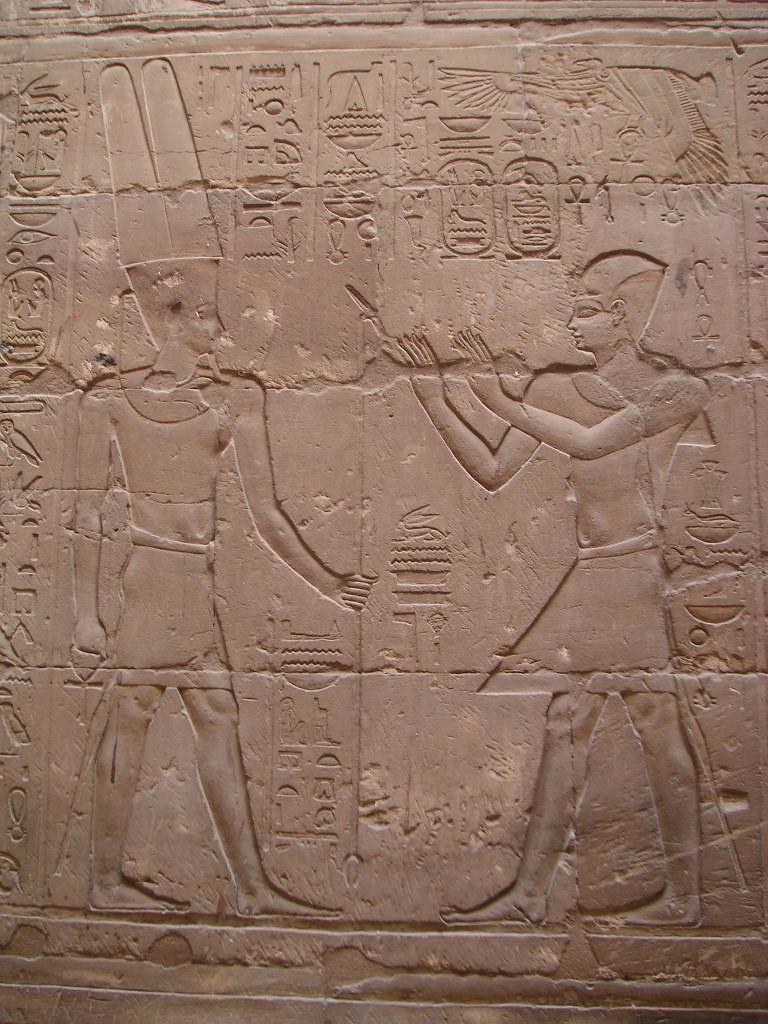

Iranian light cavalry

Phrataphernes, seeing a great victory in his grasp, now committed his heavy cavalry. The Macedonian cavalry was swept from the field, with Aristonous dying on the field, now the phalanx was isolated and started to fall apart. Despite a spirited resistance from the Macedonian troops victory was total for the rebels. Lysimachos, who was in charge of the phalanx, managed to escape the field with a small bodyguard, but most of the army did not. Lysimachos escaped west, where he relayed the news of the defeat personally to the king himself. Despite what you might expect he was not punished for the defeat, according to later sources hostile to Lysimachos that was because he unduly put all blame for the Battle of Hekatompylos on Aristonous. It is also possible Alexander did not punish him because Lysimachos was a friend of him. The victory emboldened the cause of Artaxerxes IV, and not long after the battle of Hekatompylos Phrataphernes was joined by Satibarzanes, Spitamenes and Artaxerxes IV himself, gathering an army 70000 strong at Hekatompylos. By now they must have heard of Alexander’s return to Asia, and now that they were confident in their ability to defeat the Macedonians they sought to confront him.

Alexander had now gathered his army at Arbela, which was quite different from the armies that Philip had used to conquer his empire. While still based around the phalanx as anvil and the hetairoi as hammer, Alexander deployed larger amounts of light troops, still mostly Illyrians and Thracians but by now he also employed Persian archers. The rear of the army and the baggage train was to be guarded by the troops levied from the Hellenic League, the flanks would be covered by the hypaspistai. Alexander and Krateros were also joined by Atropates, satrap of Media, with a contingent of Median cavalry. A final addition to the army, under the command of the officer Peukestas, were several thousand Persian heavy infantrymen known as the Kardakes. They were an late Achaemenid experiment in replicating the Greek hoplite infantry, armed with an aspis shield and a spear. Alexander’s cavalry, often the decisive factor in his battles, was diverse in origins. The heavy cavalry, the hetairoi, were Macedonians, and complemented by the excellent Thessalian horsemen. The light cavalry was also partially drawn from Macedon, but also included large Thracian, Armenian and now also Persian contingents. In July, eager to leave the searing heat of the Mesopotamian plains, Alexander and his army marched east, into the Zagros, where they first stopped at Ecbatana. There he was reinforced by Atropates, and he also received some good news. The rebels, emboldened by their recent success, had hoped to seize the old Achaemenid heartland by surprise. A cavalry force had been send south to Persia from Hekatompylos, but was defeated near Pasargadae by Philotas, military governor of Persia. Despite this setback Artaxerxes IV, or more likely Satibarzanes, did not relent, and the with the final confrontation with Alexander on the horizon he decided to act. The satrap’s army marched west from Hekatompylos and occupied the city of Rhagai [2] in northern Iran. It was probably there that the rebels received word from their scouts that Alexander was on his way, and it was there that they decided to confront him.

The battle was fought just west of the city, on an open plain between some hills, around the beginning of August 327. Showcasing their confidence, the leaders of the rebellion were present on the field, each of them leading their own contingents. The Bactrians and Arachosians were positioned in the centre, under Satibarzanes, on the right stood the Sogdians under Spitamenes and on the left the Parthians and Hyrcanians under Phrataphernes. Apart from a small core of heavy infantry, mostly the remaining Greek mercenaries, the satrap’s armies mostly consisted of lightly armed conscripted infantry and large amounts of cavalry. Alexander, aware that the enemy’s cavalry outnumbered his, changed his formation accordingly. Knowing that being outflanked was the bane of the phalanx he positioned his army between two hills, and stretched his phalanx between them, occupying the hills with both non-phalangite heavy infantry and light infantry. Alexander took a considerable risk by stretching his phalanx so far, but he trusted that his troops would be able to hold the line against the charge of the enemy. Deliberately he had thinned the line the most in its centre, but it was also there that he had placed his most experienced and trusted troops, under the command of his good friend Ptolemaios. The Persian and Greek infantry would form a second line behind the phalanx, to counter an enemy breakthrough, while the hypaspistai were tasked with guarding the hills that anchored the phalanx. The troops on the steep hill on the left of the Macedonian phalanx were under command of Perdiccas, while the troops on the less steep hill on the right side were commanded by Krateros. The Thessalian and Median cavalry, under command of Koinos, was stationed in front of the hill on the left side of the phalanx, tasked with threatening the enemy flank, and thus distracting at least a portion of their cavalry. They were also supported by a group of Thracian light infantry. Another detachment, consisting of Thracian cavalry under command of Seleukos, was to harass the enemy’s advance. Alexander himself and the hetairoi were stationed behind the phalanx on a slight rise, clearly visible for the enemy.

The satraps, it seems, were confident of their victory. Already twice they had managed to overcome the Macedonians, why wouldn’t they do so another time? Even Alexander’s strong defensive position did not make them hesitate. They outnumbered him almost two to one, they were deploying 70000 men while Alexander had at most 40000. There were no negotiations or parlay between the two sides on the eve of battle, both sides it seems were eager to settle accounts on the battlefield. It started early in the morning, with Parthian and Scythian cavalry darting forward, harassing the Macedonian lines from afar with their bows. They were chased off by the Thracians under Seleukos, but he had to retreat behind the phalanx when the satrap’s infantry advanced. In the meantime Koinos and his cavalry rode forth, assailing the flank of the Sogdian infantry before being chased off by Spitamenes and his cavalry. Koinos then rode west, being chased by the Sogdian cavalry and thus distracting them from the battle. The Sogdian infantry had regrouped, and started assaulting the Macedonian position on the hill to the left, but to no avail. Fighting uphill was not easy, certainly not if it was so steep. Meanwhile the Sogdians were peppered with projectiles from the light infantry further on the hill, while facing off against the prowess of the hypaspistai.

On the plains the bulk of the satrap’s infantry now started their assault on Alexander’s phalanx. Satibarzanes, himself in a chariot, followed close behind with his cavalry, hoping to exploit any gap that his infantry would make in the Macedonian ranks. On the hill to the right Phrataphernes had commenced his assault, which went noticeably better than the Sogdian assault on the hill to the left. The hill on the right was not steep, it had a relatively gentle slope, and the Hyrcanians, who made up most of Phrataphernes’ infantry, were famed as mountaineers, so they were quite used to fighting on a hillside. Slowly but surely Krateros’ troops were driven off the hilltop. Phrataphernes, seeing that the fight was going well, rode in with his bodyguard and encouraged his troops. Krateros did the same, rallying his troops, while at the same time sending a messenger to Alexander asking for reinforcements. Alexander, upon hearing the news from Krateros, immediately send the Greeks, Persians and the Thracian cavalry under Seleukos to the hill. He knew, or at least hoped, that the phalanx would hold, but he could not risk losing one of the flanks, so he send his second line to shore up Krateros’ position. This seemed to have worked, for Krateros now managed to hold out and, inch by inch, reclaimed the hilltop.

Now all of Alexander’s troop were engaged, something Satibarzanes must have noticed. He now ordered his heavy infantry onward, straight into the thinned centre of the phalanx, to finally break the Macedonians. At the same time he had some of his cavalry attempt to break through, while he would stay back with most of the cavalry to launch the final charge, making certain that the Macedonians would be routed. Little by little the Macedonian centre under Ptolemaios started falling back, though not in an uncontrolled fashion, but carefully the phalangites seemed to retreat. It was then that Alexander made his move, together with the hetairoi he rode off, seemingly in retreat. Satibarzanes must have seen the royal banner of the Argeads, a sunburst on a purple field, now seemingly moving away from the battlefield. With the Macedonian centre buckling under the weight of his assault and their king abandoning them Satibarzanes saw his chance, and now charged in with the rest of his cavalry, most notably the heavily armoured Bactrian lancers. Despite their king seemingly fleeing, the Macedonians did not rout, they only slowly gave away ground in the centre, while on the flanks the phalanx held firm. Where at first the phalanx formed a straight line, by now it was u-shaped. It is unknown whether Satibarzanes ever realized that he was walking into a trap or not, or whether he saw the royal banner reappearing on the hill to his left. Far from fleeing, Alexander and the hetairoi had ascended, out of Satibarzanes’ view, the hill to their right, from which Krateros had managed to drive away the Hyrcanians. Now Alexander and the hetairoi charged downhill, effortlessly breaking through a meagre cavalry screen and into the rear of the enemy formation, now completely surrounded. A great cheer went up from the ranks of the phalanx when they saw their king, the sun reflecting on his gilded helmet, leading the hetairoi into Satibarzanes’ ranks. Now the phalanx, who had preserved their strength for precisely this moment, started its advance into the startled ranks of their enemies, who not so long ago thought that victory was in their grasp. The satrap’s army, now compressed between the phalanx and Alexander’s cavalry, attempted to resist the Macedonian advance but to no avail, and soon afterwards panic made itself master of the rebel troops. Eager as they were to escape their encirclement many of them fell not to Macedonian arms but in a stampede by their fellow soldiers. Satibarzanes too fell on the field, supposedly after seeing Alexander storm his position he tried to escape, but his driver turned the chariot around too fast, after which Satibarzanes fell out and was crushed to death beneath the hooves of the Macedonian cavalry.

Alexander confronting Satibarzanes

Koinos in the meantime had managed to defeat the Sogdian cavalry, who were ambushed by the Thracian infantry while chasing him, after which Koinos turned his cavalry around and charged into the Sogdian ranks. The Sogdians were defeated and Spitamenes was killed in battle. Koinos returned to the field afterwards and assaulted the rebels’ rear guard, which he managed to defeat and afterwards captured their baggage train. Meanwhile Alexander had mopped up the satrap’s main force, the field now littered with the dead and the dying. The satrap’s army was crushed decisively, with thousands death and even more now destined for an inhuman and brutal life of slavery. For Alexander himself and his empire this was a great victory, more or less crushing resistance in a single battle instead of fighting a long campaign. This was mostly because of the satrap’s overconfidence, thinking that because they could beat Balakros and Aristonous on the battlefield they could also best Alexander. After the battle ‘Artaxerxes IV’ once again disappears from the record, now for good. Of the satraps only Phrataphernes survived the battle, he managed to flee the field with a small group of cavalry. He returned to the Hyrcanian capital Zadrakarta, from where he attempted to resist Alexander. The king, who had no time to besiege the city, delegated the subjugation of Hyrcania to Perdiccas, who was given 15000 men to complete his objective.

After the battle Alexander marched northeast, through the Caspian Gates and afterwards occupying Hekatompylos. After receiving the subjugation of the Parthians, and leaving behind Seleukos as satrap with a garrison, he marched further and occupied the city of Susia [3] in October 327. There he planned to stay for a couple months, waiting for additional supplies and reinforcements from the west, after which he would resume his march. Alexander himself would march north, past Merv, until he would reach the Oxus, after which he would follow the river upstream until reaching Baktra. A second force would be send south from Susia, under command of Krateros, by now a trusted confidante of Alexander, to Areia, Drangiana and Arachosia beyond. These were the plans of Alexander, hoping to finally solidify his grip on the eastern provinces of his empire.

Footnotes

In year 2 of the 113th Olympiad, in the month of Hekatombaion, the people of this city dedicated this shrine to Zeus for the safety, well-being and glory of the Great King Alexander, King of the Macedonians, Persians, Babylonians and all the peoples of Asia, Hegemon of the Hellenic League.

- Inscription at a shrine of Zeus at Nikopolis (OTL Mosul)

In June 327 Alexander reached the city of Arbela in northern Mesopotamia, where Parmenion had already gathered reinforcements for the king. His march east from Gordion had gone without incident, but once he arrived at Arbela he received news from further east. An advance force had already been send east, as requested by Alexander, under the joint command of Lysimachos and Aristonous. In March 10000 men had set out from Ecbatana under their command, marching east to confront the rebels, who had by now gathered their forces at Hekatompylos [1]. The army there was under the command of the satrap of Parthia and Hyrcania, Phrataphernes, and consisted mostly of local infantry (many recruited from the hill tribes of Hyrcania), cavalry (both local and from the steppes) and even some Greek hoplites, mercenaries that had fled east after the battle of Mepsila. Phrataphernes probably outnumbered his opponents, but not by much. Satibarzanes and ‘Artaxerxes IV’ remained in Baktra, where they were gathering a larger army for the reconquest of Persia and Mesopotamia. They had managed to destroy Balakros’ force and kill the general himself in a surprise attack in one of the many valleys of Bactria, but a war against Alexander himself would require more preparations.

Aristonous and Lysimachos were meant to assess the situation and, if possible, delay the enemy advance. Their army largely consisted of fresh recruits, few light troops to guard the flanks and not much cavalry. Reports send to the generals by spies however indicated that Phrataphernes’ army was not large, and conquering Hekatompylos would give the Macedonians an excellent base for campaigns further east. Sensing an opportunity to score a great victory Aristonous urged action, and Lysimachos acquiesced, the army marched thus marched on Hekatompylos. During their march they were almost continually harassed by Phrataphernes’ light cavalry, and the Macedonian light cavalry was ambushed while trying to drive them away. Despite these setbacks the generals decided to push on, and reached Hekatompylos in May, and to their surprise just outside the city they were confronted with the army of Phrataphernes. Because of Macedonian dominance in the open field they had expected that Phrataphernes would let it come to a siege or that he would retreat. Eager as they were the Macedonians formed up their formation and advanced on the Hyrcanian positions, the phalanx advanced while the heavy cavalry attempted to outflank the Hyrcanians. A charge of Phrataphernes’ cavalry forced the Macedonian cavalry to retreat to guard the phalanx, and they came increasingly under fire from Phrataphernes’ light cavalry, which consisted mainly of horse archers from the steppes, mostly supplied by the Dahae, and Iranian cavalry armed with javelins and axes. The Hyrcanian infantry had fallen back, but now struck the flanks of the phalanx while the Greek mercenaries managed to hold back the centre. Often armed with a bundle of javelins and an axe they managed to hack their way into the phalanx, whose long pikes were of no use in a close-hand melee. Many of the phalangites dropped their pikes and drew their swords, but that lead to less pressure against the Greek mercenaries in the centre, who were now no longer being driven back and instead managed to put pressure on the phalanx itself.

Iranian light cavalry

Phrataphernes, seeing a great victory in his grasp, now committed his heavy cavalry. The Macedonian cavalry was swept from the field, with Aristonous dying on the field, now the phalanx was isolated and started to fall apart. Despite a spirited resistance from the Macedonian troops victory was total for the rebels. Lysimachos, who was in charge of the phalanx, managed to escape the field with a small bodyguard, but most of the army did not. Lysimachos escaped west, where he relayed the news of the defeat personally to the king himself. Despite what you might expect he was not punished for the defeat, according to later sources hostile to Lysimachos that was because he unduly put all blame for the Battle of Hekatompylos on Aristonous. It is also possible Alexander did not punish him because Lysimachos was a friend of him. The victory emboldened the cause of Artaxerxes IV, and not long after the battle of Hekatompylos Phrataphernes was joined by Satibarzanes, Spitamenes and Artaxerxes IV himself, gathering an army 70000 strong at Hekatompylos. By now they must have heard of Alexander’s return to Asia, and now that they were confident in their ability to defeat the Macedonians they sought to confront him.

Alexander had now gathered his army at Arbela, which was quite different from the armies that Philip had used to conquer his empire. While still based around the phalanx as anvil and the hetairoi as hammer, Alexander deployed larger amounts of light troops, still mostly Illyrians and Thracians but by now he also employed Persian archers. The rear of the army and the baggage train was to be guarded by the troops levied from the Hellenic League, the flanks would be covered by the hypaspistai. Alexander and Krateros were also joined by Atropates, satrap of Media, with a contingent of Median cavalry. A final addition to the army, under the command of the officer Peukestas, were several thousand Persian heavy infantrymen known as the Kardakes. They were an late Achaemenid experiment in replicating the Greek hoplite infantry, armed with an aspis shield and a spear. Alexander’s cavalry, often the decisive factor in his battles, was diverse in origins. The heavy cavalry, the hetairoi, were Macedonians, and complemented by the excellent Thessalian horsemen. The light cavalry was also partially drawn from Macedon, but also included large Thracian, Armenian and now also Persian contingents. In July, eager to leave the searing heat of the Mesopotamian plains, Alexander and his army marched east, into the Zagros, where they first stopped at Ecbatana. There he was reinforced by Atropates, and he also received some good news. The rebels, emboldened by their recent success, had hoped to seize the old Achaemenid heartland by surprise. A cavalry force had been send south to Persia from Hekatompylos, but was defeated near Pasargadae by Philotas, military governor of Persia. Despite this setback Artaxerxes IV, or more likely Satibarzanes, did not relent, and the with the final confrontation with Alexander on the horizon he decided to act. The satrap’s army marched west from Hekatompylos and occupied the city of Rhagai [2] in northern Iran. It was probably there that the rebels received word from their scouts that Alexander was on his way, and it was there that they decided to confront him.

The battle was fought just west of the city, on an open plain between some hills, around the beginning of August 327. Showcasing their confidence, the leaders of the rebellion were present on the field, each of them leading their own contingents. The Bactrians and Arachosians were positioned in the centre, under Satibarzanes, on the right stood the Sogdians under Spitamenes and on the left the Parthians and Hyrcanians under Phrataphernes. Apart from a small core of heavy infantry, mostly the remaining Greek mercenaries, the satrap’s armies mostly consisted of lightly armed conscripted infantry and large amounts of cavalry. Alexander, aware that the enemy’s cavalry outnumbered his, changed his formation accordingly. Knowing that being outflanked was the bane of the phalanx he positioned his army between two hills, and stretched his phalanx between them, occupying the hills with both non-phalangite heavy infantry and light infantry. Alexander took a considerable risk by stretching his phalanx so far, but he trusted that his troops would be able to hold the line against the charge of the enemy. Deliberately he had thinned the line the most in its centre, but it was also there that he had placed his most experienced and trusted troops, under the command of his good friend Ptolemaios. The Persian and Greek infantry would form a second line behind the phalanx, to counter an enemy breakthrough, while the hypaspistai were tasked with guarding the hills that anchored the phalanx. The troops on the steep hill on the left of the Macedonian phalanx were under command of Perdiccas, while the troops on the less steep hill on the right side were commanded by Krateros. The Thessalian and Median cavalry, under command of Koinos, was stationed in front of the hill on the left side of the phalanx, tasked with threatening the enemy flank, and thus distracting at least a portion of their cavalry. They were also supported by a group of Thracian light infantry. Another detachment, consisting of Thracian cavalry under command of Seleukos, was to harass the enemy’s advance. Alexander himself and the hetairoi were stationed behind the phalanx on a slight rise, clearly visible for the enemy.

The satraps, it seems, were confident of their victory. Already twice they had managed to overcome the Macedonians, why wouldn’t they do so another time? Even Alexander’s strong defensive position did not make them hesitate. They outnumbered him almost two to one, they were deploying 70000 men while Alexander had at most 40000. There were no negotiations or parlay between the two sides on the eve of battle, both sides it seems were eager to settle accounts on the battlefield. It started early in the morning, with Parthian and Scythian cavalry darting forward, harassing the Macedonian lines from afar with their bows. They were chased off by the Thracians under Seleukos, but he had to retreat behind the phalanx when the satrap’s infantry advanced. In the meantime Koinos and his cavalry rode forth, assailing the flank of the Sogdian infantry before being chased off by Spitamenes and his cavalry. Koinos then rode west, being chased by the Sogdian cavalry and thus distracting them from the battle. The Sogdian infantry had regrouped, and started assaulting the Macedonian position on the hill to the left, but to no avail. Fighting uphill was not easy, certainly not if it was so steep. Meanwhile the Sogdians were peppered with projectiles from the light infantry further on the hill, while facing off against the prowess of the hypaspistai.

On the plains the bulk of the satrap’s infantry now started their assault on Alexander’s phalanx. Satibarzanes, himself in a chariot, followed close behind with his cavalry, hoping to exploit any gap that his infantry would make in the Macedonian ranks. On the hill to the right Phrataphernes had commenced his assault, which went noticeably better than the Sogdian assault on the hill to the left. The hill on the right was not steep, it had a relatively gentle slope, and the Hyrcanians, who made up most of Phrataphernes’ infantry, were famed as mountaineers, so they were quite used to fighting on a hillside. Slowly but surely Krateros’ troops were driven off the hilltop. Phrataphernes, seeing that the fight was going well, rode in with his bodyguard and encouraged his troops. Krateros did the same, rallying his troops, while at the same time sending a messenger to Alexander asking for reinforcements. Alexander, upon hearing the news from Krateros, immediately send the Greeks, Persians and the Thracian cavalry under Seleukos to the hill. He knew, or at least hoped, that the phalanx would hold, but he could not risk losing one of the flanks, so he send his second line to shore up Krateros’ position. This seemed to have worked, for Krateros now managed to hold out and, inch by inch, reclaimed the hilltop.

Now all of Alexander’s troop were engaged, something Satibarzanes must have noticed. He now ordered his heavy infantry onward, straight into the thinned centre of the phalanx, to finally break the Macedonians. At the same time he had some of his cavalry attempt to break through, while he would stay back with most of the cavalry to launch the final charge, making certain that the Macedonians would be routed. Little by little the Macedonian centre under Ptolemaios started falling back, though not in an uncontrolled fashion, but carefully the phalangites seemed to retreat. It was then that Alexander made his move, together with the hetairoi he rode off, seemingly in retreat. Satibarzanes must have seen the royal banner of the Argeads, a sunburst on a purple field, now seemingly moving away from the battlefield. With the Macedonian centre buckling under the weight of his assault and their king abandoning them Satibarzanes saw his chance, and now charged in with the rest of his cavalry, most notably the heavily armoured Bactrian lancers. Despite their king seemingly fleeing, the Macedonians did not rout, they only slowly gave away ground in the centre, while on the flanks the phalanx held firm. Where at first the phalanx formed a straight line, by now it was u-shaped. It is unknown whether Satibarzanes ever realized that he was walking into a trap or not, or whether he saw the royal banner reappearing on the hill to his left. Far from fleeing, Alexander and the hetairoi had ascended, out of Satibarzanes’ view, the hill to their right, from which Krateros had managed to drive away the Hyrcanians. Now Alexander and the hetairoi charged downhill, effortlessly breaking through a meagre cavalry screen and into the rear of the enemy formation, now completely surrounded. A great cheer went up from the ranks of the phalanx when they saw their king, the sun reflecting on his gilded helmet, leading the hetairoi into Satibarzanes’ ranks. Now the phalanx, who had preserved their strength for precisely this moment, started its advance into the startled ranks of their enemies, who not so long ago thought that victory was in their grasp. The satrap’s army, now compressed between the phalanx and Alexander’s cavalry, attempted to resist the Macedonian advance but to no avail, and soon afterwards panic made itself master of the rebel troops. Eager as they were to escape their encirclement many of them fell not to Macedonian arms but in a stampede by their fellow soldiers. Satibarzanes too fell on the field, supposedly after seeing Alexander storm his position he tried to escape, but his driver turned the chariot around too fast, after which Satibarzanes fell out and was crushed to death beneath the hooves of the Macedonian cavalry.

Alexander confronting Satibarzanes

Koinos in the meantime had managed to defeat the Sogdian cavalry, who were ambushed by the Thracian infantry while chasing him, after which Koinos turned his cavalry around and charged into the Sogdian ranks. The Sogdians were defeated and Spitamenes was killed in battle. Koinos returned to the field afterwards and assaulted the rebels’ rear guard, which he managed to defeat and afterwards captured their baggage train. Meanwhile Alexander had mopped up the satrap’s main force, the field now littered with the dead and the dying. The satrap’s army was crushed decisively, with thousands death and even more now destined for an inhuman and brutal life of slavery. For Alexander himself and his empire this was a great victory, more or less crushing resistance in a single battle instead of fighting a long campaign. This was mostly because of the satrap’s overconfidence, thinking that because they could beat Balakros and Aristonous on the battlefield they could also best Alexander. After the battle ‘Artaxerxes IV’ once again disappears from the record, now for good. Of the satraps only Phrataphernes survived the battle, he managed to flee the field with a small group of cavalry. He returned to the Hyrcanian capital Zadrakarta, from where he attempted to resist Alexander. The king, who had no time to besiege the city, delegated the subjugation of Hyrcania to Perdiccas, who was given 15000 men to complete his objective.

After the battle Alexander marched northeast, through the Caspian Gates and afterwards occupying Hekatompylos. After receiving the subjugation of the Parthians, and leaving behind Seleukos as satrap with a garrison, he marched further and occupied the city of Susia [3] in October 327. There he planned to stay for a couple months, waiting for additional supplies and reinforcements from the west, after which he would resume his march. Alexander himself would march north, past Merv, until he would reach the Oxus, after which he would follow the river upstream until reaching Baktra. A second force would be send south from Susia, under command of Krateros, by now a trusted confidante of Alexander, to Areia, Drangiana and Arachosia beyond. These were the plans of Alexander, hoping to finally solidify his grip on the eastern provinces of his empire.

Footnotes

- Location is disputed, most likely Shahr-i-Qumis in north-eastern Iran, which for the sake of the TL I assume is true.

- Near modern day Tehran.

- Modern day Tus in north-eastern Iran.

Last edited:

A bit later and shorter than I initially planned, work has been quite busy so I haven't been able to spend much time on the TL. This week should be somewhat less busy, so there might be another update in the weekend.

A bit later and shorter than I initially planned, work has been quite busy so I haven't been able to spend much time on the TL. This week should be somewhat less busy, so there might be another update in the weekend.

Take your time dude, RL‘s got precedence. The quality of the writing is as good as ever.

And I gotta add, the quotes at the top of every chapter really help set the dynamic for the chapter!

13. Towards the horizon

13. Towards the horizon

Alexandrou Anabasis

Having defeated the combined hosts of the eastern satraps at Rhagai, now the Great King Alexander went even further east, not stopping until he reached the Jaxartes, beyond which lies Scythia, and thus Europe. There on the banks of the river Alexander erected three shrines, one to Dionysos, one to Herakles and one to his father, Philippos Nikator, marking the border of his domains.

- Excerpt from The lives of the Great Kings of Asia by Hermocles of Brentesion

Alexander’s victory at Rhagai, one of the finest battles of his entire career, had far-reaching consequences for the eastern satrapies. In their recklessness the satraps had gambled everything on a set-piece battle with the Great King, and had lost decisively. If they had retreated and had waged a guerrilla campaign against the Macedonians in the rugged terrain of Eastern Iran, Bactria and Sogdiana their chances of victory would have been much higher. Now though, with a large part of the fighting elite dead or captive, Alexander’s campaign was comparatively much easier. That is not to say it was unopposed, not at all, but the campaign could have been much harsher on him and his army.

In January 326 Alexander resumed his march, his army now 30000 strong. It was now more multi-ethnic than it had ever been, an image of the empire he and his father had forged. Macedonian phalangites and cavalry were supported by Greek hoplites, Thracian peltasts, Babylonian spearmen, Median horsemen and Persian archers. Despite the great distance that he had covered since returning from Europe the reinforcements arrived without delay, testament to the Persian roads and logistical system, which Alexander now benefitted from. His army now well-supplied and rested the Great King marched north, following the caravan routes into the lands that were called Margiana. He encountered little resistance and in March he reached the oasis city of Merv, the capital of the region. The presence of such a large army made the choice easy for the inhabitants of Merv, they threw open their gates for Alexander, who marched into the city more like a triumphant ruler than a foreign conqueror. In his honour the city was renamed, at least officially, to Alexandria-in-Margiana.

Alexander did not remain in Margiana for long, and soon restarted his march to the Oxus. The army was rested and well-supplied, but the march through the Karakum Desert to the Oxus must have been gruelling. Upon reaching the Oxus the army once again took several days of rest, and it was probably then that Alexander received reports of what was happening in the rest of Bactria and Sogdia. The local nobility, which by and large had thrown in their lot with Spitamenes and his rebellion, were now divided over how to react to Alexander’s approach. Sensing an opportunity the surrounding nomadic tribes, the Saka, Massagetae and Dahae, launched raids into the rich lands of Sogdia and Bactria. Not long after his arrival on the Oxus Alexander caught up with and defeated a group of Dahae raiders, showing to the local population that at least he could rid of them of the nomadic threat. Marching upstream the Oxus, Alexander encountered almost no resistance and reached Bactra in June 326. Once again no resistance was offered and after some negotiations the city opened it’s gates to the Macedonians, who duly marched in and established a garrison. Using Bactra as his base Alexander led several expeditions into the Bactrian countryside, commanding a cavalry force made up from his own army and local levies. Over several months Alexander managed to drive away the Saka and Massagetae from Bactria. The decisive battle of the campaign took place at the city of Nautaka in northern Bactria, where a local nobleman named Sisimithres had joined forces with the Saka to oppose Alexander.

Using mounted archers of his own, both hired from the Dahae and recruited locally, to pin down the enemy forces in conjunction with his light infantry suppressing them with their slings, bows and javelins, Alexander managed to charge in with his hetairoi, scattering his enemies with ease. Sisimithres survived the battle and fled to his nearby stronghold, where he was subsequently besieged by Alexander. Seeing the hopelessness of his situation the Sogdian warlord surrendered and was treated gracefully, he was allowed to keep his land and life, but was ordered to hand over his sons to Alexander as hostages. Alexander returned to Bactra in October, where soon afterwards he was joined by Perdiccas and 8000 Persian reinforcements. Perdiccas had successfully concluded his campaign in Hyrcania by capturing Zadracarta, Hyrcania was subsequently added to Seleukos’ satrapy, and had now come to Bactria to reinforce Alexander. Perdiccas had also brought along the former satrap Phrataphernes, who was captured in Zadracarta. The Bactrians had for now shown themselves to be largely loyal, but only the year before the area had been the staging ground of a rebellion against him. He had to set an example so that it would be clear for all what the consequence of disobedience would be. Phrataphernes was tortured horrifically, his nose and nears were cut off, and then tied to a stake just outside Bactra, to die of exposure to the elements and exhaustion. As Alexander marched his army out of Bactra on their way north to Sogdia they marched past the dying Phrataphernes, so that they too could see the consequence of rebellion.

Death of Phrataphernes

Alexander’s next target were the lands of Sogdia, to the north of Bactria. Already the territory to Nautaka had been pacified, and Alexander managed to reach Marakanda [1], capital of Sogdia, relatively quickly. At first the city intended to resist the great conqueror, but it relented when the scope of the Macedonian siege works became apparent to them. The gates were opened and the Macedonians marched in, but despite that Alexander showed no lenience to the local rulers. The aristocracy he had decimated for daring to resist their rightful king, and a strong garrison was installed to oversee the city. In February 325 he rode out against the Massagetae who had gathered to the west of Marakanda, and managed to surprise and defeat them while their main force was trying to ford the Polytimetus [2]. Another cavalry force under joint command of Ptolemaios and Koinos defeated the vanguard of the Saka and drove them back, after which the Saka retreated behind the Jaxartes. Not long afterwards the rest of Sogdia, perhaps happy to be rid of the nomad menace, subjugated itself to Alexander.

The king now marched out again, to the shores of the Jaxartes, where on the opposite shore the Saka had gathered to repel him. Alexander, undeterred, had his engineers construct catapults and ballistae to force away the Saka from the north bank, after which Alexander and an elite corps managed to cross the river without incident. They repelled a Saka counterattack and then routed the rest of their forces. Alexander, now content, returned to the southern bank of the Jaxartes. He ordered the resettlement of Cyropolis [3] as farthest garrison of his empire, to guard against threats from across the Jaxartes. Cyropolis, as its name suggests, was once founded by Cyrus the Great to safeguard the nascent Persian Empire against nomadic threats from the north. Now Alexander imitated, and honoured, him by refounding the city. There were murmurs of discontent among the Macedonians and Greeks about naming a new settlement after a Persian king, but Alexander relented. Here are perhaps the first signs that Alexander increasingly saw himself not just as a Macedonian king but increasingly an ‘Asian’ one, who saw Cyrus as an illustrious predecessor.

After the battle at the Jaxartes Alexander returned to Bactra, leaving Sogdia behind with several garrisons. Sogdia would be joined to Bactria in a single satrapy, which was granted to Perdiccas. Alexander returned to Bactra in August 325, after which he granted his army a month of rest. In Bactra Alexander received reinforcements send by Parmenion, 8000 mercenaries recruited from Greece and Anatolia. By now the Greeks and Persians in the army must have outnumbered the Macedonians. During his time in Bactria Alexander put down a short-lived rebellion centred around the city of Drapsaka, whose entire male population was put to the sword in retaliation. He also founded the city of Philippi-on-the-Oxus [4] in eastern Bactria. In September 325 he prepared his army to march south, to cross the Hindu Kush through the Khawak Pass and to join up with Krateros in the Kabul Valley. Krateros had managed to subjugate Areia, Drangiana and Arachosia, and had shown himself the capable commander that Alexander saw in him. He was popular among the Macedonian troops but also rather conservative. He encountered little resistance during his march through Eastern Iran, but when he did he crushed it ruthlessly.

Alexander crossed the Khawak Pass with 30000 men, a great feat of endurance and logistics, and in the southern foothills of the Hindu Kush (known to the Greeks as the Paropamisos) founded the city of Alexandria-in-the-Caucasus, to secure the various passes in the region. There he exacted tribute from local tribes and awaited the arrival of Krateros, after which he would start the final part of his campaign to restore the borders of his empire, the invasion of India.

The Golden Horus

In the second regnal year under the Majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khakaura, the Son of Ra, Nakhtnebef, strong-of-arm, Beloved by Amun-Ra, his Majesty enriched the shrines of the Gods and erected numerous monuments. He was great of strength, and crushed the Nubians and the Asiatics who threatened Egypt. There were none who were like him, the Golden Horus of all lands, who upholds ma’at and smites isfet [5]. His Majesty while in the Residence received envoys from all lands, coming to offer tribute to his greatness. The Gods themselves rejoiced at this sight, and blessed His Majesty with millions of jubilees in life, prosperity and health.

- Inscription found at the Hut-Khakaura-em-Waset

His first year on the throne more or less set the tone for the rest of Nakhtnebef’s rule, an energetic ruler with a keen interest in military affairs. Late in 328 he travelled to Pelusium, where he oversaw the construction of additional defensive works. The walls were reinforced, extra towers were built, some in such a way that they could house catapults or ballistae. Further to the south, at Per-Atum, he also ordered additional defensive works. Despite his confidence and assertiveness Nakhtnebef still saw it as essential to Egypt’s security that the borders of Egypt itself were well protected.

Economically Egypt was still doing well, its goods were still sought after and it still sat astride important trade routes, gathering dues straight into the pharaonic exchequer. Somewhat worse for Egypt was a relatively low flood that year, which meant that the harvest, will still sufficient, would not be as bountiful as in previous years. It would not mean famine in Egypt, but it would mean that there was less to export. Luckily for Egypt the floods in 326 and 325 were sufficient, even if not especially good.

Nakhtnebef’s main construction projects were continuing apace. He ordered some additions to the Great Temple of Ptah at Memphis and at this time the palace at Hebyt was completed. The palace, not far from the dynastic capital at Tjebnetjer, would be the main residence for the rest of the royal family for the remainder of the Thirtieth Dynasty. The king himself did not stay there often, splitting his time between Waset and Memphis if he was not on campaign. Another project that was started around this time was the restoration of the Akh-Menu-Menkheperre [6] at Ipetsut. For Nakhtnebef this must have been an important project, both because it was centred on his favoured city and because it honoured a great conqueror whom he idolised, pharaoh Thutmose III.

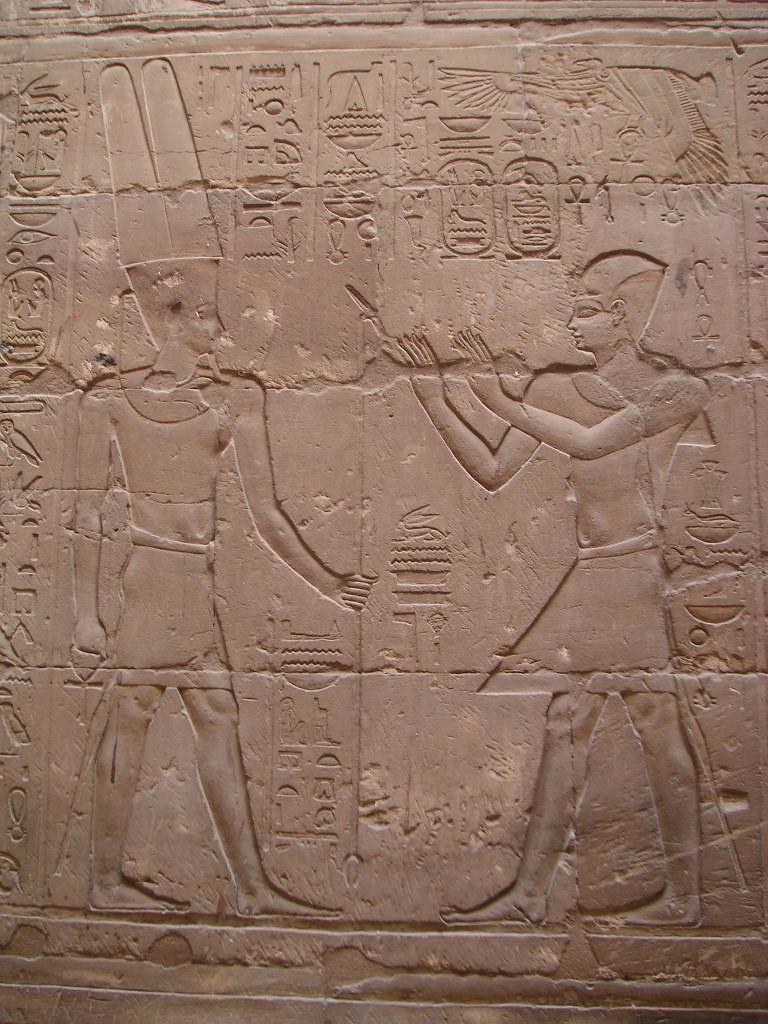

Nakhtnebef II praising Amun [7]

In 326 Nakhtnebef send his second daughter, Udjashu, to Ipetsut, to be introduced into the Cult of Amun-Ra, where she would one day succeed her aunt Iaret-Merytamun as God’s Wife of Amun. Later that year Nakhtnebef once again marched of to war, although the opponent he sought to destroy was not particularly dangerous. He marched his army, mostly machimoi and Libyans, to Gaza. From there he, supported by the local Philistians and Judeans, launched several punitive expeditions against nomadic Arabs who in the past year had raided some trade caravans. Most of the Arabs opposed to Nakhtnebef evaded his forces, familiar as they were with the local terrain. Through either luck or treachery though he did manage to catch up with and defeat several tribes. Rather arbitrarily some he punished harshly, but others were even granted land in Egypt itself, on the condition that they would faithfully serve in the pharaoh’s army. On one of the walls of the restored Akh-Menu Nakhtnebef recorded this great victory, showing himself victorious over enemies labelled as ‘Shasu’, the ancient Egyptian name for the nomadic Bedouin of the Eastern Desert. The pharaoh triumphantly strides forward, mace held high, while in front of him, much smaller, the Shasu scramble away in terror. It was certainly the way in which Nakhtnebef saw himself, a conqueror in true pharaonic fashion.

Despite this confident display of his power as a great warrior the pharaoh had suffered a particularly grievous blow during his campaign against the Shasu. During one of the skirmishes his son and co-regent, the by now 18-year old Nakhthorheb II was struck in his leg by an arrow. While at first it did not appear lethal, soon afterwards the wound got infected and after several days of high fever the co-ruler of the Nile passed away. Nakhtnebef then ended his campaign prematurely, returned to Egypt and oversaw the internment of his son in an antechamber of his own tomb at the temple of Anhur-Shu at Tjebnetjer. Nakhthorheb had been the king's only son, and with his passing the eventual succession to the Throne of Horus was once again insecure.

Footnotes

Alexandrou Anabasis

Having defeated the combined hosts of the eastern satraps at Rhagai, now the Great King Alexander went even further east, not stopping until he reached the Jaxartes, beyond which lies Scythia, and thus Europe. There on the banks of the river Alexander erected three shrines, one to Dionysos, one to Herakles and one to his father, Philippos Nikator, marking the border of his domains.

- Excerpt from The lives of the Great Kings of Asia by Hermocles of Brentesion

Alexander’s victory at Rhagai, one of the finest battles of his entire career, had far-reaching consequences for the eastern satrapies. In their recklessness the satraps had gambled everything on a set-piece battle with the Great King, and had lost decisively. If they had retreated and had waged a guerrilla campaign against the Macedonians in the rugged terrain of Eastern Iran, Bactria and Sogdiana their chances of victory would have been much higher. Now though, with a large part of the fighting elite dead or captive, Alexander’s campaign was comparatively much easier. That is not to say it was unopposed, not at all, but the campaign could have been much harsher on him and his army.

In January 326 Alexander resumed his march, his army now 30000 strong. It was now more multi-ethnic than it had ever been, an image of the empire he and his father had forged. Macedonian phalangites and cavalry were supported by Greek hoplites, Thracian peltasts, Babylonian spearmen, Median horsemen and Persian archers. Despite the great distance that he had covered since returning from Europe the reinforcements arrived without delay, testament to the Persian roads and logistical system, which Alexander now benefitted from. His army now well-supplied and rested the Great King marched north, following the caravan routes into the lands that were called Margiana. He encountered little resistance and in March he reached the oasis city of Merv, the capital of the region. The presence of such a large army made the choice easy for the inhabitants of Merv, they threw open their gates for Alexander, who marched into the city more like a triumphant ruler than a foreign conqueror. In his honour the city was renamed, at least officially, to Alexandria-in-Margiana.

Alexander did not remain in Margiana for long, and soon restarted his march to the Oxus. The army was rested and well-supplied, but the march through the Karakum Desert to the Oxus must have been gruelling. Upon reaching the Oxus the army once again took several days of rest, and it was probably then that Alexander received reports of what was happening in the rest of Bactria and Sogdia. The local nobility, which by and large had thrown in their lot with Spitamenes and his rebellion, were now divided over how to react to Alexander’s approach. Sensing an opportunity the surrounding nomadic tribes, the Saka, Massagetae and Dahae, launched raids into the rich lands of Sogdia and Bactria. Not long after his arrival on the Oxus Alexander caught up with and defeated a group of Dahae raiders, showing to the local population that at least he could rid of them of the nomadic threat. Marching upstream the Oxus, Alexander encountered almost no resistance and reached Bactra in June 326. Once again no resistance was offered and after some negotiations the city opened it’s gates to the Macedonians, who duly marched in and established a garrison. Using Bactra as his base Alexander led several expeditions into the Bactrian countryside, commanding a cavalry force made up from his own army and local levies. Over several months Alexander managed to drive away the Saka and Massagetae from Bactria. The decisive battle of the campaign took place at the city of Nautaka in northern Bactria, where a local nobleman named Sisimithres had joined forces with the Saka to oppose Alexander.

Using mounted archers of his own, both hired from the Dahae and recruited locally, to pin down the enemy forces in conjunction with his light infantry suppressing them with their slings, bows and javelins, Alexander managed to charge in with his hetairoi, scattering his enemies with ease. Sisimithres survived the battle and fled to his nearby stronghold, where he was subsequently besieged by Alexander. Seeing the hopelessness of his situation the Sogdian warlord surrendered and was treated gracefully, he was allowed to keep his land and life, but was ordered to hand over his sons to Alexander as hostages. Alexander returned to Bactra in October, where soon afterwards he was joined by Perdiccas and 8000 Persian reinforcements. Perdiccas had successfully concluded his campaign in Hyrcania by capturing Zadracarta, Hyrcania was subsequently added to Seleukos’ satrapy, and had now come to Bactria to reinforce Alexander. Perdiccas had also brought along the former satrap Phrataphernes, who was captured in Zadracarta. The Bactrians had for now shown themselves to be largely loyal, but only the year before the area had been the staging ground of a rebellion against him. He had to set an example so that it would be clear for all what the consequence of disobedience would be. Phrataphernes was tortured horrifically, his nose and nears were cut off, and then tied to a stake just outside Bactra, to die of exposure to the elements and exhaustion. As Alexander marched his army out of Bactra on their way north to Sogdia they marched past the dying Phrataphernes, so that they too could see the consequence of rebellion.

Death of Phrataphernes

Alexander’s next target were the lands of Sogdia, to the north of Bactria. Already the territory to Nautaka had been pacified, and Alexander managed to reach Marakanda [1], capital of Sogdia, relatively quickly. At first the city intended to resist the great conqueror, but it relented when the scope of the Macedonian siege works became apparent to them. The gates were opened and the Macedonians marched in, but despite that Alexander showed no lenience to the local rulers. The aristocracy he had decimated for daring to resist their rightful king, and a strong garrison was installed to oversee the city. In February 325 he rode out against the Massagetae who had gathered to the west of Marakanda, and managed to surprise and defeat them while their main force was trying to ford the Polytimetus [2]. Another cavalry force under joint command of Ptolemaios and Koinos defeated the vanguard of the Saka and drove them back, after which the Saka retreated behind the Jaxartes. Not long afterwards the rest of Sogdia, perhaps happy to be rid of the nomad menace, subjugated itself to Alexander.

The king now marched out again, to the shores of the Jaxartes, where on the opposite shore the Saka had gathered to repel him. Alexander, undeterred, had his engineers construct catapults and ballistae to force away the Saka from the north bank, after which Alexander and an elite corps managed to cross the river without incident. They repelled a Saka counterattack and then routed the rest of their forces. Alexander, now content, returned to the southern bank of the Jaxartes. He ordered the resettlement of Cyropolis [3] as farthest garrison of his empire, to guard against threats from across the Jaxartes. Cyropolis, as its name suggests, was once founded by Cyrus the Great to safeguard the nascent Persian Empire against nomadic threats from the north. Now Alexander imitated, and honoured, him by refounding the city. There were murmurs of discontent among the Macedonians and Greeks about naming a new settlement after a Persian king, but Alexander relented. Here are perhaps the first signs that Alexander increasingly saw himself not just as a Macedonian king but increasingly an ‘Asian’ one, who saw Cyrus as an illustrious predecessor.

After the battle at the Jaxartes Alexander returned to Bactra, leaving Sogdia behind with several garrisons. Sogdia would be joined to Bactria in a single satrapy, which was granted to Perdiccas. Alexander returned to Bactra in August 325, after which he granted his army a month of rest. In Bactra Alexander received reinforcements send by Parmenion, 8000 mercenaries recruited from Greece and Anatolia. By now the Greeks and Persians in the army must have outnumbered the Macedonians. During his time in Bactria Alexander put down a short-lived rebellion centred around the city of Drapsaka, whose entire male population was put to the sword in retaliation. He also founded the city of Philippi-on-the-Oxus [4] in eastern Bactria. In September 325 he prepared his army to march south, to cross the Hindu Kush through the Khawak Pass and to join up with Krateros in the Kabul Valley. Krateros had managed to subjugate Areia, Drangiana and Arachosia, and had shown himself the capable commander that Alexander saw in him. He was popular among the Macedonian troops but also rather conservative. He encountered little resistance during his march through Eastern Iran, but when he did he crushed it ruthlessly.

Alexander crossed the Khawak Pass with 30000 men, a great feat of endurance and logistics, and in the southern foothills of the Hindu Kush (known to the Greeks as the Paropamisos) founded the city of Alexandria-in-the-Caucasus, to secure the various passes in the region. There he exacted tribute from local tribes and awaited the arrival of Krateros, after which he would start the final part of his campaign to restore the borders of his empire, the invasion of India.

The Golden Horus

In the second regnal year under the Majesty of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khakaura, the Son of Ra, Nakhtnebef, strong-of-arm, Beloved by Amun-Ra, his Majesty enriched the shrines of the Gods and erected numerous monuments. He was great of strength, and crushed the Nubians and the Asiatics who threatened Egypt. There were none who were like him, the Golden Horus of all lands, who upholds ma’at and smites isfet [5]. His Majesty while in the Residence received envoys from all lands, coming to offer tribute to his greatness. The Gods themselves rejoiced at this sight, and blessed His Majesty with millions of jubilees in life, prosperity and health.

- Inscription found at the Hut-Khakaura-em-Waset

His first year on the throne more or less set the tone for the rest of Nakhtnebef’s rule, an energetic ruler with a keen interest in military affairs. Late in 328 he travelled to Pelusium, where he oversaw the construction of additional defensive works. The walls were reinforced, extra towers were built, some in such a way that they could house catapults or ballistae. Further to the south, at Per-Atum, he also ordered additional defensive works. Despite his confidence and assertiveness Nakhtnebef still saw it as essential to Egypt’s security that the borders of Egypt itself were well protected.

Economically Egypt was still doing well, its goods were still sought after and it still sat astride important trade routes, gathering dues straight into the pharaonic exchequer. Somewhat worse for Egypt was a relatively low flood that year, which meant that the harvest, will still sufficient, would not be as bountiful as in previous years. It would not mean famine in Egypt, but it would mean that there was less to export. Luckily for Egypt the floods in 326 and 325 were sufficient, even if not especially good.

Nakhtnebef’s main construction projects were continuing apace. He ordered some additions to the Great Temple of Ptah at Memphis and at this time the palace at Hebyt was completed. The palace, not far from the dynastic capital at Tjebnetjer, would be the main residence for the rest of the royal family for the remainder of the Thirtieth Dynasty. The king himself did not stay there often, splitting his time between Waset and Memphis if he was not on campaign. Another project that was started around this time was the restoration of the Akh-Menu-Menkheperre [6] at Ipetsut. For Nakhtnebef this must have been an important project, both because it was centred on his favoured city and because it honoured a great conqueror whom he idolised, pharaoh Thutmose III.

Nakhtnebef II praising Amun [7]

In 326 Nakhtnebef send his second daughter, Udjashu, to Ipetsut, to be introduced into the Cult of Amun-Ra, where she would one day succeed her aunt Iaret-Merytamun as God’s Wife of Amun. Later that year Nakhtnebef once again marched of to war, although the opponent he sought to destroy was not particularly dangerous. He marched his army, mostly machimoi and Libyans, to Gaza. From there he, supported by the local Philistians and Judeans, launched several punitive expeditions against nomadic Arabs who in the past year had raided some trade caravans. Most of the Arabs opposed to Nakhtnebef evaded his forces, familiar as they were with the local terrain. Through either luck or treachery though he did manage to catch up with and defeat several tribes. Rather arbitrarily some he punished harshly, but others were even granted land in Egypt itself, on the condition that they would faithfully serve in the pharaoh’s army. On one of the walls of the restored Akh-Menu Nakhtnebef recorded this great victory, showing himself victorious over enemies labelled as ‘Shasu’, the ancient Egyptian name for the nomadic Bedouin of the Eastern Desert. The pharaoh triumphantly strides forward, mace held high, while in front of him, much smaller, the Shasu scramble away in terror. It was certainly the way in which Nakhtnebef saw himself, a conqueror in true pharaonic fashion.

Despite this confident display of his power as a great warrior the pharaoh had suffered a particularly grievous blow during his campaign against the Shasu. During one of the skirmishes his son and co-regent, the by now 18-year old Nakhthorheb II was struck in his leg by an arrow. While at first it did not appear lethal, soon afterwards the wound got infected and after several days of high fever the co-ruler of the Nile passed away. Nakhtnebef then ended his campaign prematurely, returned to Egypt and oversaw the internment of his son in an antechamber of his own tomb at the temple of Anhur-Shu at Tjebnetjer. Nakhthorheb had been the king's only son, and with his passing the eventual succession to the Throne of Horus was once again insecure.

Footnotes

- AKA Samarkand

- The Zeravshan river

- OTL Alexandria Eschate

- OTL Ai-Khanoum

- Chaos and injustice, opposite of ma’at

- ‘Effective are the monuments of Menkheperre’ i.e. the Festival Hall of Thutmose III at Karnak, OTL restorations were made in name of Alexander.

- OTL this is actually Alexander in Pharaonic garb worshipping Amun

Last edited:

Alexander's the Dweller on the Threshold atm, I can't wait for this invasion of India. I wonder which Porus he's going to encounter upon his entry or if he's gonna go for Taxila and Peucela first.

Something went wrong while posting update, the last paragraph was lost. It is added now.

Donald Reaver

Donor

Damn, big miss in posting. Interesting days in a succession is rarely a good thing.

Thanks, I hope that Alexander's campaign up till now makes sense. I'll hope you don't mind if I'll send you some questions about India via PM.Alexander's the Dweller on the Threshold atm, I can't wait for this invasion of India. I wonder which Porus he's going to encounter upon his entry or if he's gonna go for Taxila and Peucela first.

Nakhtnebef does have the advantage that he isn't that old yet, so he could still produce an heir an raise him till maturity.Damn, big miss in posting. Interesting days in a succession is rarely a good thing.

Thanks, I hope that Alexander's campaign up till now makes sense. I'll hope you don't mind if I'll send you some questions about India via PM.

It definitely does! Bactria and Sogdia were more connected to the Greek world than a lot of closer locations like, say Cilicia, so it makes sense that he would focus on subjugating them.

And totally, I've been reading through a variety of pre-Mauryan secondary sources recently so feel free to ask.

The next update should be up by sometime next week, I'm not sure yet exactly when. I'd also like to thank anyone who read, liked or commented on the timeline, it means a lot to me to see that people are interested in my writings.

Last edited:

If that were too happen, then it would be likely that Egypt would try to expand its borders to the Euphrates, more or less replicating the situation as it was under the Eighteenth Dynasty.Alexander is close to reaching the borders he ruled OTL, save for Egypt. If Alexander receives a stray arrow or an infectious disease in India without a clear heir, his empire might disintegrate worse than in OTL. Will Egypt be picking up some of the pieces?

Sorry about the recent lack of updates, the reason for which is that I managed to catch the coronavirus. For some days last week I felt pretty bad, but I'm doing much better now. I'm hoping to have the next update up somewhere next week.

Donald Reaver

Donor

Glad to hear you are doing better, take care of yourself.Sorry about the recent lack of updates, the reason for which is that I managed to catch the coronavirus. For some days last week I felt pretty bad, but I'm doing much better now. I'm hoping to have the next update up somewhere next week.

Im also glad to hear you're feeling better. Rest and relax.Sorry about the recent lack of updates, the reason for which is that I managed to catch the coronavirus. For some days last week I felt pretty bad, but I'm doing much better now. I'm hoping to have the next update up somewhere next week.

Alexander is long married with a Persian princessWhy is Alexander still single? Phillip would have long since had him wedded having lived this long.

Threadmarks

View all 97 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

72. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 1 73. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 2 74. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 3 Interlude: Argead rule in Asia Interlude VII 75. Strong are the Manifestations of the Ka of Ra 76. Intrigue in Eupatoria 77. The early 220's around the Aegean

Share: