In the event of there being a break between the "core" Greek parts of the Macedonian Empire and its eastern territories, I feel a dynastic schism is certainly possible. One Argead scion from a branch raised in Macedon as Macedonians, another from the "regnal" line (probably raised in Babylon) with a more cosmopolitan and imperial mindset. Not sure if the latter group would want such a situation to occur, but if things get dire enough the former clique may have the space to make their move.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Horus Triumphant - an Alternate Antiquity timeline

- Thread starter phoenix101

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 97 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

72. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 1 73. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 2 74. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 3 Interlude: Argead rule in Asia Interlude VII 75. Strong are the Manifestations of the Ka of Ra 76. Intrigue in Eupatoria 77. The early 220's around the AegeanI wonder how the Argeads ITTL will deal with the incoming Celtic migrations to the Balkans.

Probably the same as the Illyrians.I wonder how the Argeads ITTL will deal with the incoming Celtic migrations to the Balkans.

Will it even come to this?I wonder how the Argeads ITTL will deal with the incoming Celtic migrations to the Balkans.

The Argead Empire here takes on the role of the Roman Empire, danube frontier and all that(roughly the Moesia part).

There are two reasons for that

I. it is a good defense line

II. Alexander, stepping into the Persian inheritance, has some reason to expand there...Dareios I. reached the Danube frontier too

A stronger defense means that the Celts probably will seek easier targets...Italy comes to mind

For the Argead dynasty Macedonia is the heartland and main source of their military power, so they will be interested to see the land there peacified. Of course, using the Macedonian armies in the East and India will keep them away from Europe...

The obvious answer is to invest in & expend Macedonia northward as much as possible. It would be interesting if the Argead can grow the region even half as large as Rome did.

How much northward Macedonia can even expand? The empire probably tries create easily defendable borderline so it has not invest so much on fight against barbarian tribes. And expansion wouldn't solve Macedonian problems. It would has still low population and quiet peripherial region.

I'm not saying this is exactly what's gonna happen, but it's not very far off.In the event of there being a break between the "core" Greek parts of the Macedonian Empire and its eastern territories, I feel a dynastic schism is certainly possible. One Argead scion from a branch raised in Macedon as Macedonians, another from the "regnal" line (probably raised in Babylon) with a more cosmopolitan and imperial mindset. Not sure if the latter group would want such a situation to occur, but if things get dire enough the former clique may have the space to make their move.

With the much richer lands to the east I don't think it's very likely that many Macedonians would want to settle further north, there'll probably be some garrisons but nothing on scale of what the Romans did OTL.The obvious answer is to invest in & expend Macedonia northward as much as possible. It would be interesting if the Argead can grow the region even half as large as Rome did.

I wonder how the Argeads ITTL will deal with the incoming Celtic migrations to the Balkans.

Harshly, I suspect.

It also depends on the timing of the invasion, but it's unlikely the Celts will be as successful as they were OTL on the Balkans if they do choose to invade.Probably the same as the Illyrians.

The Danube is the official border, but there isn't much of a Macedonian presence there outside of some small garrisons to keep watch on the Getai and the Thracians. Your assertion that a strong Argead Empire will deter some of the Celts in favour of easier targets is correct.Will it even come to this?

The Argead Empire here takes on the role of the Roman Empire, danube frontier and all that(roughly the Moesia part).

There are two reasons for that

I. it is a good defense line

II. Alexander, stepping into the Persian inheritance, has some reason to expand there...Dareios I. reached the Danube frontier too

A stronger defense means that the Celts probably will seek easier targets...Italy comes to mind

For the Argead dynasty Macedonia is the heartland and main source of their military power, so they will be interested to see the land there peacified. Of course, using the Macedonian armies in the East and India will keep them away from Europe...

With the east opened up to colonization there won't be much northwards Macedonian expansion.How much northward Macedonia can even expand? The empire probably tries create easily defendable borderline so it has not invest so much on fight against barbarian tribes. And expansion wouldn't solve Macedonian problems. It would has still low population and quiet peripherial region.

Two things:

1. I try to keep the TL updated weekly, but I can't promise anything for next week.

2. Big thanks to all the people who voted for this TL in the Turtledoves! It's really great to see.

1. I try to keep the TL updated weekly, but I can't promise anything for next week.

2. Big thanks to all the people who voted for this TL in the Turtledoves! It's really great to see.

26. Carthage 315-305

26. Carthage 315-310

Abdmelqart, son of Gersakun, was honoured in those days as the saviour of the state by many. Yet there were also those who were fearful, who remembered what happened when Abdmelqart’s grandfather had also achieved such popularity, and they wondered if he might follow in his footsteps. It was this tension that was the backdrop of the politics of the City after the war against Alexander.

- Excerpt from History of the Kan'anim by Abdashtart, son of Hanno

Despite losing territory on Sicily, including several long-standing Phoenician settlements and valued allies of the republic, many saw the outcome of the war between the Argead Empire and Carthage as an Carthaginian victory. This is not entirely without merit, Alexander had failed in his intention of ‘liberating’ all of Sicily, the naval battle at the Aiginates was a disaster for the Argeads and both the siege of Lilybaion and the African campaign ended in disappointment for the Great King of Asia. This was certainly the prevalent view among most of the Carthaginians, or at least those who supported the dominant faction of the Gersakunids [1].

In the aftermath of the war however many among the Carthaginian aristocracy, the great landholders and merchants, started to worry about Abdmelqart’s popularity. His victories at Tunes and the heroic resistance at Lilybaion had, in the eyes of many Carthaginians, been the reason that Carthage remained an independent state. After the peace treaty was signed Abdmelqart had entered the city in a triumphant parade, and the Assembly voted him extraordinary honours. Despite his popularity he declined to run for any of the important offices, yet he did make known which candidates he preferred, ensuring that his supporters would be elected. This was concerning to many among the Carthaginian oligarchy, for this seemed to echo the acts of Hanno, Abdmelqarts’ grandfather. Something had to be done to stop his ascent.

In 315 one of the elected suffetes was Hanno of Tharros, the great victor of the battle of the Aiginates. He too had been backed by Abdmelqart and he must have seemed to be a loyal member of the Gersakunid faction. The surprise must have been great then, when in that year the Court of 104 decided to investigate the conduct of Abdmelqart during the recent war. After all, Carthage had lost territory and its sphere of influence on Sicily. Hanno of Tharros presided over the meetings of the Court, which consisted of members of the Adirim, and surprisingly did not veto its proceedings. The Adirim consisted of the wealthiest and most prestigious among the aristocracy, and they were the ones who feared Abdmelqart the most. In the end they declared that Abdmelqart had been negligent during the conflict on Sicily. They knew however that crucifying him would be out of line, he was still popular after all. Abdmelqart was fined instead and barred from running for office.

Overnight Hanno of Tharros became the leading figure of the anti-Gersakunid faction, which was mostly based among the wealthy landholders and merchants. For several years afterwards the suffetes were split, one would belong to the Gersakunid faction and one to the faction of Hanno of Tharros. Abdmelqart, eager to show that he had no autocratic tendencies, gracefully acknowledged the verdict of the 104 and retired from politics and from the City itself, choosing to live in one of his countryside villas. The Assembly, which in Carthage was relatively powerful, was still dominated by the Gersakunids. Political polarization became rife in those days, with plenty of intimidation, frivolous court cases and occasional violence against opponents. If the supporters of the Gersakunids supported something their opponents would naturally oppose it, even if it did benefit the republic, and vice-versa. Still, the Gersakunids had an edge through their domination of the Assembly, which had the deciding vote if a matter could not be decided by the Adirim and the suffetes.

Despite this political paralysis Carthage itself managed to recover relatively quickly from the war. Carthage and its hinterlands had not suffered much during Nikanor’s invasion and still produced an ample agricultural bounty. Trade with the Eastern Mediterranean also picked up again relatively quickly, aided of course by Carthage’s natural position as a nexus of trade between the two halves of the Mediterranean. During the war, while Alexander was on Sicily, the chiliarch Antigonos had managed to negotiate the submission of Phoenicia to the Argead Empire, which now meant that Tyre was part of Alexander’s empire. While probably somewhat awkward for the Carthaginians themselves it also meant that the Tyrians could act as intermediaries between Babylon and Carthage, and the regular embassies that brought gifts to the temple of Melqart in Tyre also functioned as emissaries to the Argead court. Trade with Egypt also became increasingly important, the Egyptians were interested in the Spanish silver the Carthaginians could provide in exchange for Egyptian dyed cloths and incense from Arabia.

The picture that thus emerges from Carthage in the late 4th Century BCE is thus of a state prosperous but politically paralysed. For some time this was not a problem, trade continued apace, Alexander did not appear to preparing for a rematch and the Libyan hinterlands were more or less pacified. Crisis however came in 309 BCE when a military expedition against an uprising in Sardinia ended in disaster, the commanding general, a general named Hannibal, was slain as were many of his troops. Hannibal had neglected to consistently pay his mercenaries, and with his death they decided to take their pay themselves and joined the rebels in plundering the island. Quickly another force was gathered and was placed under the command of Adherbal, son of Baalyaton [2]. Libyan infantry, Celtic warriors, Greek hoplites and Iberian swordsmen were camped near Carthage while awaiting their transport to Sardinia. Political machinations however had considerably slowed down the campaign, Adherbal was, in contrast to Hannibal, a member of the Gersakunid faction, and even before he could command his army he had already been accused by some among the Adirim of embezzling the funds meant for the mercenaries. While Sardinia burned Carthage only send some meagre reinforcements, and the mercenaries received practically no pay at all. It could have been not much of a surprise then when early in 308 the unpaid mercenaries also revolted, which instigated an uprising among the Libyans.

Confronted with such a threat quickly calls arose among the Carthaginians for Abdmelqart to be given the command against the rebels. The Adirim, of course, resisted. When the mercenaries plundered the countryside and blockaded the city itself panic broke out and riots started. Hanno of Tharros relented, and he recommended the recall of Abdmelqart to the Adirim, who decided to agree. Abdmelqart himself, like his father before him, was gracious to his opponents, who he did not prosecute for what they had done to him. During 308 and 307 he campaigned against the revolting mercenaries, who despite their martial prowess were not as threatening as they might have been. There had been no central leadership, no motivation except loot, and the once intimidating mercenary force fell apart rather quickly when Abdmelqart decisively defeated them in several battles. Several groups even rejoined the Carthaginian military, while others were massacred to the man. Knowing that it was necessary to grant his former opponents some glory too Abdmelqart made sure that Hanno of Tharros would be in charge of the expedition to Sardinia, which was finally pacified again in 306. In the subsequent year the two former rivals even shared the suffeteship.

Despite this seeming reconciliation it was now clear for all to see that it was once again Abdmelqart and the Gersakunids that were the dominant faction in Carthage, and for some years his enemies would indeed lay low. While strictly he was never a tyrant or monarch through his prestige and influence Abdmelqart would for several decades be more or less the first citizen of the Carthaginian Republic.

Footnotes

Abdmelqart, son of Gersakun, was honoured in those days as the saviour of the state by many. Yet there were also those who were fearful, who remembered what happened when Abdmelqart’s grandfather had also achieved such popularity, and they wondered if he might follow in his footsteps. It was this tension that was the backdrop of the politics of the City after the war against Alexander.

- Excerpt from History of the Kan'anim by Abdashtart, son of Hanno

Despite losing territory on Sicily, including several long-standing Phoenician settlements and valued allies of the republic, many saw the outcome of the war between the Argead Empire and Carthage as an Carthaginian victory. This is not entirely without merit, Alexander had failed in his intention of ‘liberating’ all of Sicily, the naval battle at the Aiginates was a disaster for the Argeads and both the siege of Lilybaion and the African campaign ended in disappointment for the Great King of Asia. This was certainly the prevalent view among most of the Carthaginians, or at least those who supported the dominant faction of the Gersakunids [1].

In the aftermath of the war however many among the Carthaginian aristocracy, the great landholders and merchants, started to worry about Abdmelqart’s popularity. His victories at Tunes and the heroic resistance at Lilybaion had, in the eyes of many Carthaginians, been the reason that Carthage remained an independent state. After the peace treaty was signed Abdmelqart had entered the city in a triumphant parade, and the Assembly voted him extraordinary honours. Despite his popularity he declined to run for any of the important offices, yet he did make known which candidates he preferred, ensuring that his supporters would be elected. This was concerning to many among the Carthaginian oligarchy, for this seemed to echo the acts of Hanno, Abdmelqarts’ grandfather. Something had to be done to stop his ascent.

In 315 one of the elected suffetes was Hanno of Tharros, the great victor of the battle of the Aiginates. He too had been backed by Abdmelqart and he must have seemed to be a loyal member of the Gersakunid faction. The surprise must have been great then, when in that year the Court of 104 decided to investigate the conduct of Abdmelqart during the recent war. After all, Carthage had lost territory and its sphere of influence on Sicily. Hanno of Tharros presided over the meetings of the Court, which consisted of members of the Adirim, and surprisingly did not veto its proceedings. The Adirim consisted of the wealthiest and most prestigious among the aristocracy, and they were the ones who feared Abdmelqart the most. In the end they declared that Abdmelqart had been negligent during the conflict on Sicily. They knew however that crucifying him would be out of line, he was still popular after all. Abdmelqart was fined instead and barred from running for office.

Overnight Hanno of Tharros became the leading figure of the anti-Gersakunid faction, which was mostly based among the wealthy landholders and merchants. For several years afterwards the suffetes were split, one would belong to the Gersakunid faction and one to the faction of Hanno of Tharros. Abdmelqart, eager to show that he had no autocratic tendencies, gracefully acknowledged the verdict of the 104 and retired from politics and from the City itself, choosing to live in one of his countryside villas. The Assembly, which in Carthage was relatively powerful, was still dominated by the Gersakunids. Political polarization became rife in those days, with plenty of intimidation, frivolous court cases and occasional violence against opponents. If the supporters of the Gersakunids supported something their opponents would naturally oppose it, even if it did benefit the republic, and vice-versa. Still, the Gersakunids had an edge through their domination of the Assembly, which had the deciding vote if a matter could not be decided by the Adirim and the suffetes.

Despite this political paralysis Carthage itself managed to recover relatively quickly from the war. Carthage and its hinterlands had not suffered much during Nikanor’s invasion and still produced an ample agricultural bounty. Trade with the Eastern Mediterranean also picked up again relatively quickly, aided of course by Carthage’s natural position as a nexus of trade between the two halves of the Mediterranean. During the war, while Alexander was on Sicily, the chiliarch Antigonos had managed to negotiate the submission of Phoenicia to the Argead Empire, which now meant that Tyre was part of Alexander’s empire. While probably somewhat awkward for the Carthaginians themselves it also meant that the Tyrians could act as intermediaries between Babylon and Carthage, and the regular embassies that brought gifts to the temple of Melqart in Tyre also functioned as emissaries to the Argead court. Trade with Egypt also became increasingly important, the Egyptians were interested in the Spanish silver the Carthaginians could provide in exchange for Egyptian dyed cloths and incense from Arabia.

The picture that thus emerges from Carthage in the late 4th Century BCE is thus of a state prosperous but politically paralysed. For some time this was not a problem, trade continued apace, Alexander did not appear to preparing for a rematch and the Libyan hinterlands were more or less pacified. Crisis however came in 309 BCE when a military expedition against an uprising in Sardinia ended in disaster, the commanding general, a general named Hannibal, was slain as were many of his troops. Hannibal had neglected to consistently pay his mercenaries, and with his death they decided to take their pay themselves and joined the rebels in plundering the island. Quickly another force was gathered and was placed under the command of Adherbal, son of Baalyaton [2]. Libyan infantry, Celtic warriors, Greek hoplites and Iberian swordsmen were camped near Carthage while awaiting their transport to Sardinia. Political machinations however had considerably slowed down the campaign, Adherbal was, in contrast to Hannibal, a member of the Gersakunid faction, and even before he could command his army he had already been accused by some among the Adirim of embezzling the funds meant for the mercenaries. While Sardinia burned Carthage only send some meagre reinforcements, and the mercenaries received practically no pay at all. It could have been not much of a surprise then when early in 308 the unpaid mercenaries also revolted, which instigated an uprising among the Libyans.

Confronted with such a threat quickly calls arose among the Carthaginians for Abdmelqart to be given the command against the rebels. The Adirim, of course, resisted. When the mercenaries plundered the countryside and blockaded the city itself panic broke out and riots started. Hanno of Tharros relented, and he recommended the recall of Abdmelqart to the Adirim, who decided to agree. Abdmelqart himself, like his father before him, was gracious to his opponents, who he did not prosecute for what they had done to him. During 308 and 307 he campaigned against the revolting mercenaries, who despite their martial prowess were not as threatening as they might have been. There had been no central leadership, no motivation except loot, and the once intimidating mercenary force fell apart rather quickly when Abdmelqart decisively defeated them in several battles. Several groups even rejoined the Carthaginian military, while others were massacred to the man. Knowing that it was necessary to grant his former opponents some glory too Abdmelqart made sure that Hanno of Tharros would be in charge of the expedition to Sardinia, which was finally pacified again in 306. In the subsequent year the two former rivals even shared the suffeteship.

Despite this seeming reconciliation it was now clear for all to see that it was once again Abdmelqart and the Gersakunids that were the dominant faction in Carthage, and for some years his enemies would indeed lay low. While strictly he was never a tyrant or monarch through his prestige and influence Abdmelqart would for several decades be more or less the first citizen of the Carthaginian Republic.

Footnotes

- See update 21, named for Gersakun (Gisgo), the son of Hanno and father of Abdmelqart

- He also featured during the Argead-Carthaginian conflict, see update 21

Last edited:

Interesting. Hopefully Carthage learns that "keep the mercenaries paid" should always be priority number 1 when you depend on them for your military.

The lesson has been learned, at least for now. Of course in comparison to the OTL rather savage Mercenary War Carthage was rather lucky, there were some small scale Libyan uprisings but nothing like OTL and the rebels did not have the leadership they had OTL.Interesting. Hopefully Carthage learns that "keep the mercenaries paid" should always be priority number 1 when you depend on them for your military.

The Carthaginians probably thought that the promise of pay would be enough to keep them in line, which was true for some time until the campaign got delayed. It's true that it was a stupid decision, but those happen sometimes.Why would they sit mercenaries at the gate of their city unpaid and neglected? Even if politically divided that should have been a no brainer, esp. given their prosperity.

Last edited:

27. The Saunitai War

27. The Saunitai War

The enemy we faced in the hills of Italy was unlike any other we had faced before, brave, cunning and ruthless, even men who had faced off against the elephants of India feared the Saunitai more than any other.

- Excerpt from Ptolemaios’ The Wars of Megas Alexandros

Alexander returned to Babylon in triumph in June 309. Symbolising his victory over India he entered the city in a chariot pulled by an elephant. The spoils of the campaign were of course displayed to the populace, although they were more meagre than those of earlier campaigns. Alexander had after all been on the defence, his campaign to India was one to repel an attack on his own territories. Several days of games and festival followed, and Alexander ordered the construction of a new temple to Dionysos (who, according to Greek legend, had also conquered India). In Alexander’s absence the empire had been ruled by the ever-active chiliarch Antigonos. He was a just and able ruler and no noteworthy problems had arisen during the Indian campaign, at least outside of Italy.

When Alexander had left behind Italy in 316 BCE the Greek cities had nominally been united under the Italiote League while several Italian peoples had offered their submission to Alexander. Ptolemaios, close friend and companion of the Great King, had been left in charge of a 10000 strong garrison at the city of Taras, and thus acted as Alexander’s representative in the region. While probably none of the Hellenic cities of Italy were eager members of the Italiote League it at least provided protection against the native population. These fierce tribes of the Italian hills and highlands had often opposed Hellenic colonization and were regularly successful against them, until Alexander’s arrival in the region. He had forced the Bruttians and Lucanians to accept his sovereignty, and in Alexander’s inscriptions in Persia they are named as one of his subject peoples; their tribute consisting of cattle and horses, testament to their relative poverty. The Saunitai (Samnites) were the mightiest of these confederacies. They menaced both the Hellenic cities of Italy and the various native powers, and when Alexander arrived in Italy they were fighting a war against the rising power of the Roman Republic. Alexander, at insistence of the local Greeks, allied himself with the Romans and thus ‘contained’ the Saunitai, who quickly thereafter signed peace out of fear of fighting on multiple fronts against such powerful opponents.

For a decade peace reigned in southern Italy, a rarity in those days. It was in late 310, when Alexander was campaigning in India, that war flared up again in Italy. The precise reason is unknown, but later sources put the blame on the Lucanians, who supposedly were in conflict with the Saunitai over pasture grounds. Whatever the reason, once again the Saunitai donned their plumed helmets, put on their cuirasses and descended from the hills to plunder the rich lowlands. In Taras the representatives of the Italiote League petitioned Ptolemaios to defend them, and in Alexander’s absence he was named general of the forces of the League. Envoys were also send to Krateros and Antigonos to ask for help. Early in 309 Ptolemaios set out of Taras with 15000 men, near the river Aufidus he confronted a Saunitai force as large as his and managed to defeat it. On the flat plains on the banks of the Aufidus the Saunitai were unable to break through the phalanx, and a force of Thessalian cavalry supplied by Krateros charged into their flank, scattering the Saunitai. For Ptolemaios the war must have seemed to be going well. The Romans, honouring their alliance, restarted the war in Campania, rooting out several Saunitai garrisons and putting them to rout. In this they were supported by 5000 Sicilian Greek troops under command of Ptolemaios’ brother Menelaus, send in by sea from Syracuse. Disaster struck however later that year in June, when an Italiot army under command of Medeios, a deputy of Ptolemaios, marched into Lucania to support the Lucanians against Saunitai raids they were ambushed near Potentia. There in the hills the Macedonian phalanx and shock cavalry were at the mercy of the Saunitai, who with their large shields, short stabbing swords and bundles of javelins were ideally equipped to fight pitched battles in a rough environment.

Potentia was important, for not long afterwards it seemed the Lucanians wavered in their support now that the Argead forces were unable to defend them against the Saunitai. One of Ptolemaios’ largest problems was his lack of manpower, the Italiote Greeks were either incapable or unreliable and his own Macedonian core were too few. Some reinforcements were send over, but most of the elite forces were still in the east. Luckily for Ptolemaios there was another source of reliable manpower nearby. The young king Neoptolemos II of Epiros, nephew of the Great King Alexander and grandson of Philippos Nikator, was an ambitious man, yet he was also just another vassal king in the vast Argead Empire. Eager to prove himself he offered his and his army’s service, and the Epirote king crossed over to Italy in August 309. The Kingdom of Epiros was a dwarf in comparison to the vast Argead Empire, but it did maintain a professional army trained in the Macedonian fashion. Leonnatos, a childhood friend of Ptolemaios and the Great King himself, had long commanded the Macedonian garrison that both guarded and kept watch on the Epirote Aiakid dynasty, and became a close companion and mentor to Neoptolemos and he made sure the kingdom’s army was well-equipped and trained. Epirote soldiers had served under Alexander, for which the kingdom was richly rewarded, and had repelled some raids by Illyrian pirates, but the chance for a victorious campaign in Italy was too good to pass up for the young and ambitious Neoptolemos. The 25000 strong Epirote army joined up with Italiote forces at Taras and started it’s march on Saunitis (Samnium) almost immediately.

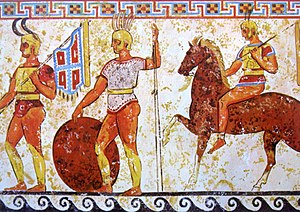

Saunitai warriors

The Italiote-Epirote forces, under joint command of Neoptolemos and Menelaus, quickly engaged and defeated some Saunitai warbands in the coastal plains. Perhaps inspired by the campaigns of his uncle and grandfather Neoptolemos decided to take his chance and strike at the heart of the Saunitai Confederacy. The Saunitai had no real cities, they lived in small towns spread across their hilly homeland were they herded their flocks, and for a king acquainted with the luxuries of the Argead court the pickings were slim. Neoptolemos however did not seek wealth but glory, and in his hurry he rushed to his doom. Despite his assault on Saunitis it seemed the Saunitai were unwilling to face him in open battle, but they did keep harassing his supply lines and his scouting parties. Lulled into a false sense of security Neoptolemos must have been surprised when the Saunitai managed to trap his army in a valley near Aikoulanon [2]. Several attempts were made to break out, none were successful. After several weeks the Saunitai finally launched their assault, and the Epirotes, wrecked by hunger and disease, broke under their onslaught. Neoptolemos lost his life, Menelaus was one of the few who managed to escape and personally relayed the bad news to his brother in Taras.

For the Saunitai victory now followed victory, and after Aikoulanon they shifted their attention to Campania. A battle against the Romans near Nola ended in a victory for the Saunitai and the defeat and destruction of a Roman consular army. Not long after the coastal cities of Campania were put under siege. Cities such as Neapolis however would not fall, they were supplied from sea and the Saunitai lacked the engineers for the construction of siege weapons. Despite the destruction of the Epirote army at Aikoulanon the Saunitai did not seem to have resumed their offensive against Megale Hellas, instead focussing on the Romans. Nonetheless the death of Neoptolemos and his army was a great shock, not just to Epiros but to the whole Hellenic world. It was perhaps what finally convinced Alexander himself to intervene. Commanding 30000 of his most elite troops he left Babylon in December 309, boarding a fleet in Cilicia and crossing over to Macedonia early in 308. He deliberately passed through Epiros on his way to Taras, where he met with his sister Cleopatra. She had already been regent during her son Neoptolemos’ childhood, now she would once again be regent for his successor, the infant Aiakides. In this she was once again aided by Leonnatos. The arrival of the Great King himself once again changed the focus of the Saunitai, who knew that if they would manage to defeat him their supremacy in southern Italy would be unquestioned.

Sadly for them, Alexander was no Neoptolemos. Alexander also knew that just by his very presence the balance of power of the conflict had shifted, for the Saunitai could not ignore his and his army’s presence, despite him not making any aggressive moves for now. Alexander spend several weeks in Taras, where he made donations to local temples and organised games in honour of himself and the gods. This was done both to display his wealth and to improve the morale of the Italiotes and the army. He marched out in March 308, and soon news reached Alexander that a Saunitai force was marching down the Bradanus river, confident and eager to defeat the Great King of Asia. The battle was fought near Herakleia, but was little more than a skirmish. Alexander’s superior cavalry quickly forced the Saunitai to retreat, perhaps somewhat eager to draw Alexander into the hills and crush him there, like they had done with Neoptolemos. It was in April 308 that battle was joined at Forentum, a Saunitai town upstream the Bradanus. Having gathered most of their forces to stop Alexander, for the Saunitai it would be the decisive battle.

But the troops they now faced were not the Epirotes of Neoptolemos, most of whom only occasionally fought against Illyrian raiders, but the elite regiments of the Argyraspidai who had faced off against Shriyaka’s elephants at the Hydaspes. Always flexible, Alexander had many of his troops equipped not with the long sarissa but with the weapons of the peltast; a round shield, sword and a bundle of javelins. The Saunitai, to their credit, fought bravely. They hurled their javelins into the phalanx, and with their large shields and swords attempted to break into the formation by sheer force of their numbers. They were however outmatched, Alexander’s own infantry outflanked them, and his cavalry, especially those recruited among the tribes off the Hindu Kush accustomed to fighting in hills and mountains, managed to shatter their flank. Against the elites of the Great King of Asia, it seemed, there could be no victory. The decisive cavalry charge, consisting of the Median cavalry, was led by the prince Philip, Alexander’s eldest son. He rushed his cavalry through a gap in the Saunitai lines and fell upon their rear. Another cavalry detachment, which played a crucial role by defeating the Saunitai cavalry early in battle, was led by Demetrios, son of the chiliarch Antigonos. Alexander himself could be proud, both of his son Philip and his son-in-law Demetrios, who had married Philip’s twin sister Cleopatra the previous year.

Now the Saunitai offered their submission, the only thing they could do to stave off even greater disaster. Alexander was magnanimous in his victory, although he did levy from them a heavy tribute. The Saunitai and their land were rather poor, so it was in men for the army and cattle that they would pay for the privilege of being considered the Great King’s servants. Curiously Alexander did not order them to evacuate their holdings in Campania, which was now partitioned between Greek cities on the coast, inland Saunitai settlements and a Roman ruled region around Capua. The Romans felt betrayed by this, but could do little against it but complain to Alexander. When their ambassador met the Great King he had already, for the last time in his life, crossed the Adriatic and was in Epidamnos. He waved away the Roman concerns, offered them some monetary compensation and send the ambassador away, hoping that that would settle it.

Footnotes

The enemy we faced in the hills of Italy was unlike any other we had faced before, brave, cunning and ruthless, even men who had faced off against the elephants of India feared the Saunitai more than any other.

- Excerpt from Ptolemaios’ The Wars of Megas Alexandros

Alexander returned to Babylon in triumph in June 309. Symbolising his victory over India he entered the city in a chariot pulled by an elephant. The spoils of the campaign were of course displayed to the populace, although they were more meagre than those of earlier campaigns. Alexander had after all been on the defence, his campaign to India was one to repel an attack on his own territories. Several days of games and festival followed, and Alexander ordered the construction of a new temple to Dionysos (who, according to Greek legend, had also conquered India). In Alexander’s absence the empire had been ruled by the ever-active chiliarch Antigonos. He was a just and able ruler and no noteworthy problems had arisen during the Indian campaign, at least outside of Italy.

When Alexander had left behind Italy in 316 BCE the Greek cities had nominally been united under the Italiote League while several Italian peoples had offered their submission to Alexander. Ptolemaios, close friend and companion of the Great King, had been left in charge of a 10000 strong garrison at the city of Taras, and thus acted as Alexander’s representative in the region. While probably none of the Hellenic cities of Italy were eager members of the Italiote League it at least provided protection against the native population. These fierce tribes of the Italian hills and highlands had often opposed Hellenic colonization and were regularly successful against them, until Alexander’s arrival in the region. He had forced the Bruttians and Lucanians to accept his sovereignty, and in Alexander’s inscriptions in Persia they are named as one of his subject peoples; their tribute consisting of cattle and horses, testament to their relative poverty. The Saunitai (Samnites) were the mightiest of these confederacies. They menaced both the Hellenic cities of Italy and the various native powers, and when Alexander arrived in Italy they were fighting a war against the rising power of the Roman Republic. Alexander, at insistence of the local Greeks, allied himself with the Romans and thus ‘contained’ the Saunitai, who quickly thereafter signed peace out of fear of fighting on multiple fronts against such powerful opponents.

For a decade peace reigned in southern Italy, a rarity in those days. It was in late 310, when Alexander was campaigning in India, that war flared up again in Italy. The precise reason is unknown, but later sources put the blame on the Lucanians, who supposedly were in conflict with the Saunitai over pasture grounds. Whatever the reason, once again the Saunitai donned their plumed helmets, put on their cuirasses and descended from the hills to plunder the rich lowlands. In Taras the representatives of the Italiote League petitioned Ptolemaios to defend them, and in Alexander’s absence he was named general of the forces of the League. Envoys were also send to Krateros and Antigonos to ask for help. Early in 309 Ptolemaios set out of Taras with 15000 men, near the river Aufidus he confronted a Saunitai force as large as his and managed to defeat it. On the flat plains on the banks of the Aufidus the Saunitai were unable to break through the phalanx, and a force of Thessalian cavalry supplied by Krateros charged into their flank, scattering the Saunitai. For Ptolemaios the war must have seemed to be going well. The Romans, honouring their alliance, restarted the war in Campania, rooting out several Saunitai garrisons and putting them to rout. In this they were supported by 5000 Sicilian Greek troops under command of Ptolemaios’ brother Menelaus, send in by sea from Syracuse. Disaster struck however later that year in June, when an Italiot army under command of Medeios, a deputy of Ptolemaios, marched into Lucania to support the Lucanians against Saunitai raids they were ambushed near Potentia. There in the hills the Macedonian phalanx and shock cavalry were at the mercy of the Saunitai, who with their large shields, short stabbing swords and bundles of javelins were ideally equipped to fight pitched battles in a rough environment.

Potentia was important, for not long afterwards it seemed the Lucanians wavered in their support now that the Argead forces were unable to defend them against the Saunitai. One of Ptolemaios’ largest problems was his lack of manpower, the Italiote Greeks were either incapable or unreliable and his own Macedonian core were too few. Some reinforcements were send over, but most of the elite forces were still in the east. Luckily for Ptolemaios there was another source of reliable manpower nearby. The young king Neoptolemos II of Epiros, nephew of the Great King Alexander and grandson of Philippos Nikator, was an ambitious man, yet he was also just another vassal king in the vast Argead Empire. Eager to prove himself he offered his and his army’s service, and the Epirote king crossed over to Italy in August 309. The Kingdom of Epiros was a dwarf in comparison to the vast Argead Empire, but it did maintain a professional army trained in the Macedonian fashion. Leonnatos, a childhood friend of Ptolemaios and the Great King himself, had long commanded the Macedonian garrison that both guarded and kept watch on the Epirote Aiakid dynasty, and became a close companion and mentor to Neoptolemos and he made sure the kingdom’s army was well-equipped and trained. Epirote soldiers had served under Alexander, for which the kingdom was richly rewarded, and had repelled some raids by Illyrian pirates, but the chance for a victorious campaign in Italy was too good to pass up for the young and ambitious Neoptolemos. The 25000 strong Epirote army joined up with Italiote forces at Taras and started it’s march on Saunitis (Samnium) almost immediately.

Saunitai warriors

The Italiote-Epirote forces, under joint command of Neoptolemos and Menelaus, quickly engaged and defeated some Saunitai warbands in the coastal plains. Perhaps inspired by the campaigns of his uncle and grandfather Neoptolemos decided to take his chance and strike at the heart of the Saunitai Confederacy. The Saunitai had no real cities, they lived in small towns spread across their hilly homeland were they herded their flocks, and for a king acquainted with the luxuries of the Argead court the pickings were slim. Neoptolemos however did not seek wealth but glory, and in his hurry he rushed to his doom. Despite his assault on Saunitis it seemed the Saunitai were unwilling to face him in open battle, but they did keep harassing his supply lines and his scouting parties. Lulled into a false sense of security Neoptolemos must have been surprised when the Saunitai managed to trap his army in a valley near Aikoulanon [2]. Several attempts were made to break out, none were successful. After several weeks the Saunitai finally launched their assault, and the Epirotes, wrecked by hunger and disease, broke under their onslaught. Neoptolemos lost his life, Menelaus was one of the few who managed to escape and personally relayed the bad news to his brother in Taras.

For the Saunitai victory now followed victory, and after Aikoulanon they shifted their attention to Campania. A battle against the Romans near Nola ended in a victory for the Saunitai and the defeat and destruction of a Roman consular army. Not long after the coastal cities of Campania were put under siege. Cities such as Neapolis however would not fall, they were supplied from sea and the Saunitai lacked the engineers for the construction of siege weapons. Despite the destruction of the Epirote army at Aikoulanon the Saunitai did not seem to have resumed their offensive against Megale Hellas, instead focussing on the Romans. Nonetheless the death of Neoptolemos and his army was a great shock, not just to Epiros but to the whole Hellenic world. It was perhaps what finally convinced Alexander himself to intervene. Commanding 30000 of his most elite troops he left Babylon in December 309, boarding a fleet in Cilicia and crossing over to Macedonia early in 308. He deliberately passed through Epiros on his way to Taras, where he met with his sister Cleopatra. She had already been regent during her son Neoptolemos’ childhood, now she would once again be regent for his successor, the infant Aiakides. In this she was once again aided by Leonnatos. The arrival of the Great King himself once again changed the focus of the Saunitai, who knew that if they would manage to defeat him their supremacy in southern Italy would be unquestioned.

Sadly for them, Alexander was no Neoptolemos. Alexander also knew that just by his very presence the balance of power of the conflict had shifted, for the Saunitai could not ignore his and his army’s presence, despite him not making any aggressive moves for now. Alexander spend several weeks in Taras, where he made donations to local temples and organised games in honour of himself and the gods. This was done both to display his wealth and to improve the morale of the Italiotes and the army. He marched out in March 308, and soon news reached Alexander that a Saunitai force was marching down the Bradanus river, confident and eager to defeat the Great King of Asia. The battle was fought near Herakleia, but was little more than a skirmish. Alexander’s superior cavalry quickly forced the Saunitai to retreat, perhaps somewhat eager to draw Alexander into the hills and crush him there, like they had done with Neoptolemos. It was in April 308 that battle was joined at Forentum, a Saunitai town upstream the Bradanus. Having gathered most of their forces to stop Alexander, for the Saunitai it would be the decisive battle.

But the troops they now faced were not the Epirotes of Neoptolemos, most of whom only occasionally fought against Illyrian raiders, but the elite regiments of the Argyraspidai who had faced off against Shriyaka’s elephants at the Hydaspes. Always flexible, Alexander had many of his troops equipped not with the long sarissa but with the weapons of the peltast; a round shield, sword and a bundle of javelins. The Saunitai, to their credit, fought bravely. They hurled their javelins into the phalanx, and with their large shields and swords attempted to break into the formation by sheer force of their numbers. They were however outmatched, Alexander’s own infantry outflanked them, and his cavalry, especially those recruited among the tribes off the Hindu Kush accustomed to fighting in hills and mountains, managed to shatter their flank. Against the elites of the Great King of Asia, it seemed, there could be no victory. The decisive cavalry charge, consisting of the Median cavalry, was led by the prince Philip, Alexander’s eldest son. He rushed his cavalry through a gap in the Saunitai lines and fell upon their rear. Another cavalry detachment, which played a crucial role by defeating the Saunitai cavalry early in battle, was led by Demetrios, son of the chiliarch Antigonos. Alexander himself could be proud, both of his son Philip and his son-in-law Demetrios, who had married Philip’s twin sister Cleopatra the previous year.

Now the Saunitai offered their submission, the only thing they could do to stave off even greater disaster. Alexander was magnanimous in his victory, although he did levy from them a heavy tribute. The Saunitai and their land were rather poor, so it was in men for the army and cattle that they would pay for the privilege of being considered the Great King’s servants. Curiously Alexander did not order them to evacuate their holdings in Campania, which was now partitioned between Greek cities on the coast, inland Saunitai settlements and a Roman ruled region around Capua. The Romans felt betrayed by this, but could do little against it but complain to Alexander. When their ambassador met the Great King he had already, for the last time in his life, crossed the Adriatic and was in Epidamnos. He waved away the Roman concerns, offered them some monetary compensation and send the ambassador away, hoping that that would settle it.

Footnotes

- Also known as Paestum.

- Known in Latin as Aeclanum.

Last edited:

Huh.

So, Rome has their ambitions in Campania stifled at best. Crippled at worse. The only place left for them to expand into is up north, but that leaves them with the problem of a Etruria that can appeal for Argead support in return for submission.

Meanwhile, the Samnites might be getting the better deal in the long term here. They now get to become soldiers in one of the strongest armies of the known world.

So, Rome has their ambitions in Campania stifled at best. Crippled at worse. The only place left for them to expand into is up north, but that leaves them with the problem of a Etruria that can appeal for Argead support in return for submission.

Meanwhile, the Samnites might be getting the better deal in the long term here. They now get to become soldiers in one of the strongest armies of the known world.

The Romans are going to end up fighting the Argeads in the long term, aren't they?

An interesting idea. Maybe his successors will eventually be challenged to create a more flexible and mobile form of infantry than the phalanx, leading them towards adopting Italic-like models like the Triplex Acies from either the Samnites or the Romans. Maybe the concept of the cohort could emerge early on, but we'll see.Samnites might induce a change in the Phalanx of the Greeks just as it had in the Romans OTL as they serve in the Argead Empire.

Rome might be more successful in Eturia than in Magna Graecia and Campania since inevitably Alexander is going to die and his successor might either be too busy governing his empire or uninterested in devoting a campaign further into the Italian Peninsula.So, Rome has their ambitions in Campania stifled at best. Crippled at worse. The only place left for them to expand into is up north, but that leaves them with the problem of a Etruria that can appeal for Argead support in return for submission.

They definitely could.Rome might be more successful in Eturia than in Magna Graecia and Campania since inevitably Alexander is going to die and his successor might either be too busy governing his empire or uninterested in devoting a campaign further into the Italian Peninsula.

Rome is probably a lot more stable this time around in the same time period too. The second war was interrupted and brought to an earlier peace, and they were forced to consolidate earlier than they'd like, especially with the meager gains the war delivered. Less drastic inequality, in as fast a time. This is good for Rome in in my opinion.

I'm guessing the senators that wanted the fertile Campanian region will lick their wounds and pivot. They could attempt to intervene in the Etrurian league's fractiousness or disunity. Or maybe it was just looser league. They still gave Rome a run for their money for a while though.

At this stage, the Samnites would just be another ethnic group amongst the hundreds that make up the Argead Empire’s territories. And a lot of the defeats later Hellenistic kingdoms suffered against Rome can be attributed to other factors, such as a lack of cavalry to make up the difference, the political systems of the Hellenistic states and lax form of warfare they were used to, and having a lot less manpower at their disposal. The Phalanx is just one part of the overall Alexandrian battle plan.Samnites might induce a change in the Phalanx of the Greeks just as it had in the Romans OTL as they serve in the Argead Empire.

Threadmarks

View all 97 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

72. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 1 73. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 2 74. Anarchy around the Aegean, part 3 Interlude: Argead rule in Asia Interlude VII 75. Strong are the Manifestations of the Ka of Ra 76. Intrigue in Eupatoria 77. The early 220's around the Aegean

Share: