17. Matters of Empire

17. Matters of Empire

A beardless king

In the third year of the 114th Olympiad, when Archippos was Archon at Athens and when Alexander, son of Philip, had been Great King of Asia for eight years, the King married Nitokris, daughter of the King of Egypt, and afterwards ventured forth from Babylon during the month of Gamelion and with his army waged war on the Cossaeans. They had never been submitted and would not accept a foreign ruler, and they were reviled among the Medes and Persians for their banditry. Eager to prove himself to his subjects and to be the first to subjugate an unconquered people the King left the city for the mountains of Susiana, despite warnings from the Chaldeans that ill omens had been observed.

- Excerpt from The lives of the Great Kings of Asia by Hermocles of Brentesion

Alexander married his new Egyptian wife in November 322, after the return of Hieronymos and his embassy to Babylon. Nitokris was settled together with some courtiers who had travelled with her from Egypt in a wing of the Palace of Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon. Alexander seems to have regarded the marriage as purely political, a sign that the King of Egypt recognized that Alexander was his superior, and it seems that he and Nitokris were never very affectionate. His marriage with Artakama too had been a political ploy, but it seems they at least grew fond of each other. For Nitokris it must have been hard, she spoke barely any Greek and no Persian or Aramaic, and was rather isolated outside of her small circle of Egyptian courtiers. Arrangements were made however to make her feel at home, including the construction of a small shrine to Isis at the palace.

For Alexander’s subjects, both Persian and Macedonian, his second marriage was another affirmation of his traditional kingship, for both peoples were used to their rulers being polygamous. This was important, for in many ways Alexander was an atypical king, for both the Macedonians and the Persians. Starting with his very appearance; on all his portraits he appears beardless, with long flowing hair and an upwards gaze and always youthful, a far cry from the stern bearded rulers that preceded him in both Persia and Macedon. The men of his generation, like Ptolemaios, Seleukos and Lysimachos, followed their king’s example and also were clean shaven. It mostly spread among the Macedonian nobility, the Persians and other easterners seemed to have mostly kept their beards. He also attempted to somewhat syncretize the outward image of both monarchies. Alexander adopted the white robes of the Persian monarchy, but rejected the tiara, instead of which he wore the Hellenic diadem, a broad purple silk ribbon ending in a knot which surrounded the king’s head. Among the Hellenes it was also used to crown victorious athletes, giving Alexander an explicit connection to Hellenic traditions and victory itself.

Victory too was what Alexander hoped to achieve when he left Babylon in January 321, leading 20000 men against the Cossaeans, a people who lived north of Susiana and were never subjugated by the Achaemenids. Like the Uxians they controlled mountain passes and started raiding trade caravans when the Macedonians decided not to pay them off. It was supposed to be a short and victorious campaign but it turned out to be quite hazardous. Marching up the Eulaios it was near the upper reaches of that river that the army’s vanguard was ambushed. Alexander, who led the vanguard, rallied his bodyguard and charged into the Cossaean lines, forcing them back and allowing the rest of his troops to regroup. This they did, but during the charge Alexander was hit in his shoulder by a javelin, after which he fell from his horse. The bodyguard fell back and defended their king, and when the Macedonian main force arrived the Cossaeans were decisively routed. Alexander, despite his wounds, continued leading the campaign. The Cossaeans were granted no mercy, and after three months of campaigning Alexander had decimated them, destroying their strongholds and forcing them out of the mountains. Alexander returned to Babylon in April 321, after another brutal campaign.

Bust of Alexander, with his usual youthful appearance

Despite the relative unimportance of the campaign it had big consequences for Alexander himself, who for the rest of his life suffered from pain in his right shoulder, where he was hit by the javelin. It did not impair him at first, but later on in his life he would no longer fight in the front lines due to the pain and stiffness of his shoulder. For now however Alexander could still lead his armies and soon after returning to Babylon he already readied his forces for the next campaign. In June 321 Alexander was in Herakleia-on-the-Tigris (OTL Charax) where under the supervision of his admiral Nearchos a fleet had been constructed, consisting of 30 quadriremes and 90 triremes, meant for the subjugation of the lands on the Arabian coasts of the Persian Gulf. Gerrha, located on the south coast of the gulf and an important centre of trade with India overseas and Southern Arabia via the caravan routes, was the King’s first target. The Gerrhaeans must have been aware of who they were dealing with, and wisely did not resist and offered their submission when the royal fleet appeared, the city’s rulers accepted a garrison and agreed to pay tribute to Alexander. Afterwards the fleet went onwards to Tylos (Bahrain), an island in the gulf that was the centre of the pearl trade. A small show of force was all what was needed to convince the Tylians that resistance was futile, and Alexander, seeing the potential of the isle as a centre of trade, founded a city on the island which he named Alexandria-on-Tylos, but which came to be known just as Tylos.

The Great King stayed on the island for two months, receiving envoys from nearby communities and overseeing the arrival of the first Greek settlers. After personally marking the boundaries of his new city the King left Tylos and sailed east alongside the coast with his fleet, not encountering any large settlements until he reached a city on the coast in the region that was the former Achaemenid satrapy of Maka, he disembarked with his army and quickly accepted the surrender of the locals. What they named their hometown is unknown, but Alexander renamed it to Apollonia [1]. The city was an important trade centre for a city further inland, known to the Hellenes as Mileia [2] and not long after Alexander’s conquest a messenger arrived from the ruler of Mileia demanding that the invaders leave. This off course only aggravated the Great King of Asia, who send the Mileian ruler, a man named Melichos in the Greek sources, an ultimatum: either submit and be spared or resist and be destroyed. No reply came, and thus Alexander marched inland with a picked force, 12000 strong, a relatively small force were he campaigning in India but here in Arabia it was a vast army, which no local ruler could hope to match.

The march to Mileia was gruelling, but Alexander was well-prepared, aware as he was of the desert conditions of the area camels were brought along from Persia for transport of supplies and water. Most of the locals also turned out to be quite willing to supply Alexander’s army with water and food. Around the end of September 321 he reached the vicinity of Mileia, where he was confronted by Melichos, who decided to gamble everything on a clash on the open field instead of a siege. Sadly for him his troops were no match for Alexander’s crack troops, who easily routed the Arabs. Mileia fell after a short siege, Melichos was captured and crucified for his attempt at resisting the Argeads. Alexander left behind a small garrison, consisting of his most recalcitrant troops, in Mileia and returned to Apollonia. There he made offerings to Zeus and had a shrine constructed to him. Maka would be an independent satrapy with Apollonia as its capital, but Argead control never reached far beyond the walls of that city, with the more inland communities practically independent and only occasionally sending tribute to the city. Laomedon of Mytilene, a personal friend of the King and brother of the satrap of Ariana Erigyius, was made satrap of Maka. It does not appear to have been a demanding job, for despite staying satrap of Maka for the rest of his life we often find Laomedon at the court in Babylon, indicating that most of the work was done by his deputies.

Leaving Apollonia behind Alexander and the fleet proceeded onward towards the city of Omana (Sohar in Oman), also located on the coast east of Mileia and a centre of copper production. Perhaps they had heard of the grim fate of Melichos and his compatriots, or they were aware of the reputation of the Great King, but as soon as the fleet appeared before the city envoys were send by the rulers of the city who offered their subjugation to Alexander. He accepted, and Omana and its environs would also become part of the satrapy of Maka, giving the Argeads at least nominally the control over the entire Persian Gulf. Harmozeia (Hormuz) in Carmania was Alexander’s next port of call. Carmania had been a somewhat troubled satrapy, Philip had left it’s satrap Aspastes in place and so did Alexander, but during Alexander’s Indian campaign Aspastes had tried to launch a rebellion, but his attempt was crushed by Philotas. Philotas had, probably after consulting with Alexander, appointed Kleandros, brother of Koinos, as satrap of Carmania. While in Harmozeia however Alexander received several local delegations, all of whom derided Kleandros as a cruel and merciless tyrant. He had been corrupt and even sacrilegious, forbidding the Iranians from exposing their dead to the elements as is usual in the Zoroastrian tradition. Alexander had Kleandros removed from his post and executed, probably more for his corruption than anything else, but to the Iranians it must have seemed as if the Great King was willing to protect them too. There were some murmurs of discontent among the Macedonian nobility, but no open hostility, they too knew that corruption and cruelty could not be abided by their king. Koinos, who had been so crucial during the campaigns in Sogdiana and India, was appointed as his brother’s replacement in Carmania, a slightly puzzling choice, but perhaps Alexander wanted to give Koinos a chance to redeem the family name.

Alexander returned to Babylon via Persepolis in December 321. His campaign had been a great success, he had managed to consolidate his control over the Persian Gulf and the maritime route to India, increasing trade and prosperity in the region. For several months he remained in the city, receiving envoys, settling disputes, presiding over festivals and other kingly duties. The more tedious tasks of government he left to the chiliarch Antigonos and to Eumenes. For now it seemed the empire Alexander and his father had built was doing well, their far-reaching conquests had united various peoples and their lands, opening up new trade routes and opportunities. The treasury of the empire was healthy, despite a tendency by Alexander to grant lavish gifts of gold and silver to those he favoured. Taxing the population and trade, plunder from campaigns and the revenue from the mines and forests of the empire, who stood under direct state control, all ensured that Alexander was the world’s richest man by a fair margin. The government of the empire however was a delicate balancing act on Alexander’s part. On one hand he had to placate the Macedonians, who still formed the professional core of his army and who expected their king, who was after all first and foremost the king of Macedonia, to treat them preferentially. On the other hand were the Asian inhabitants of the empire, primarily the Persians and Medes, but the Babylonians, Syrians, Sogdians and Indians were important too. For them Alexander tried, and mostly succeeded, to play the role of rightful Great King of Asia and heir to the Achaemenid dynasty.

The gargantuan resources that were at his disposal enabled Alexander to embark upon several building and infrastructural projects. The Palace of Nebuchadnezzar at Babylon was renovated, adding a distinct Hellenic flair to the building. Babylon’s Hellenic district, known as the Philippeion, also saw the construction of a large theatre and a temple to Artemis, both sponsored by the Great King himself. The city’s harbour on the Euphrates was also expanded, making it possible to accommodate larger ships and thus making trade via the river more convenient. These were however small projects in comparison with the wholesale construction of cities elsewhere in Mesopotamia, Syria and the Upper Satrapies [3]. These cities, planned in a grid pattern and mostly settled by Alexander’s veterans and immigrants from the Aegean, would be the backbone of Argead rule in the Near East.

Alexander did not stay in Babylon for very long, restless as he often was. Already he was planning new military campaigns, first he would subjugate the south coast of the Black Sea and then he would launch a pincer attack on the Caucasus, he himself would march in from the west while Krateros and Philotas would charge in from Media and Armenia respectively. Just before the start of the campaign Peukestas was send east to Arachosia with 15000 men, including a large force of Persian phalangites, to help supressing a revolt there. Peukestas was a natural fit to lead a mixed force, being one of the few Macedonians who were genuinely interested in Persian culture he even learned to speak their language. Alexander himself set off in March 320, marching up the Euphrates and through Syria, where he inspected the new city of Nikatoris-on-the-Orontes. The construction works in Nikatoris had not gone well, and the person who was in charge of it, a childhood friend of the King named Harpalos, had seemingly vanished into thin air with funds meant for construction of the city not long before the King’s arrival. While in Nikatoris a delegation arrived from Epiros, send by his mother; requesting aid from the Great King. For a short while it seems the King hesitated, but in the end he relented. News had also reached him of unrest in Macedon and Greece, and perhaps he was eager to see Hephaistion again after many years. Whatever the case the Caucasus campaign was abandoned for now, instead the Great King of Asia would march west.

Western affairs

Were we to consider what was the greatest city of the Hellenes at the time of Alexander than we can safely ignore Sparta, defeated and dejected, or Athens, proud but subjugated. Neither are it the brave Boeotians, the men of Thebes, or the Corinthians, powerless before Alexander’s men on the Acrocorinth. No, it is to Sicily, to they who drink the waters of Arethusa, majestic Syracuse, greatest polis of the Hellenes, that we must look.

- Excerpt from Antikles of Massalia’s History of the Hellenes vol. 3: from Philippos Nikator to the Polemarcheia

When Alexander of Epiros left the Italian peninsula in 331 BCE he left behind a garrison in the city of Taras, to safeguard it against the encroaching Saunitai (Samnites). When he died several years later his widow Cleopatra became regent for the boy king Neoptolemos II and was backed up by a Macedonian army under Leonnatos and the authority of her own mother Olympias. With Epiros now more or less a Macedonian vassal Taras became the most western outpost of an empire stretching to the foothills of the Himalaya. While the Saunitai were still a threat the Tarentines remained docile, and on one occasion Leonnatos himself crossed the Adriatic with a combined Macedonian-Epirote force and defeated Saunitai raiders who threatened the city. By the late 320’s however the situation had changed. The city of Rome, the greatest power of the middle of the peninsula and chief city of the Latins, expanded it sphere of influence southwards, to the fertile plains of Campania, which were also coveted by the Saunitai. Conflict broke out between the two, and for several years the hills of southern Italia were drenched with blood. It was a merciless conflict, exemplified by the fact that that one point the Saunitai managed to trap a Roman army in the valley of Caudine Forks and massacred them completely. The war dragged on, and the pressure that the Saunitai exerted on the Greek cities of Megale Hellas, including Taras, diminished.

Thus the Tarentines in 321, eager to finally be rid of the Epirotes and their Macedonian masters, evicted the garrison. While they were entrenched in a fortress either by treachery or bribery it fell, and the soldiers were either massacred or sold into slavery. The Tarentines calculated that the Epirotes might have had something better to do, and in this they were partially right for the Illyrians were once again becoming a problem, raiding coastlines and terrorizing traders in the Adriatic. Yet Tarentine treachery would not be forgiven nor forgotten by Olympias and Cleopatra, who requested aid from Hephaistion, who complied and send them some forces. The Epirote army, trained in the Macedonian way of war, complemented with Hephaistion’s forces, was a potent force. When the Tarantines noticed that the Epirotes would not relent and that they would be up against the might of Macedonia itself they attempted to form a defensive league with the other cities of Megale Hellas, as they had done in the past to see off threats. Now however the other cities of Megale Hellas, such as Kroton, Rhegion and Herakleia decided to ignore Taras’ pleas for help. Desperate for allies, Taras thus turned to the western Hellenes’ greatest city for aid, hoping that its new and unpredictable ruler would be willing to help them.

Agathokles

Syracuse’s history in the preceding century had been one of ups and downs. Under Dionysius I, a ruthless tyrant whose professional mercenary army and state apparatus might be seen as a precursor to Alexander and Philip, it had reached the zenith of its power. It had almost driven the Carthaginians [4] of the island and had expanded its sphere of influence in Megale Hellas. Dionysius I was seen as cruel and vindictive, yet also a patron of artists and philosophers. His son Dionysius II however was less than capable and ousted in a coup, although later on he would regain his throne only to be overthrown once again. In 343 Timoleon, originally from Syracuse’s mother city of Corinth, managed to take control of the city and installed a democratic government. His most famous act was the defeat of the Carthaginians at the river Crimissus in 339. After Timoleon’s death Syracuse once again fell into bloody civil strife and factionalism. An oligarchy was established, but Syracuse was still rather unstable. The situation came ahead in 322 BC, when Agathokles [5], a military man with a knack for populism gathered a mercenary force and managed to overthrow the oligarchic regime. He announced the formal restoration of democracy, but by merit of his sizeable army he practically was the new tyrant. Making use of his army he captured Akragas and Gela, making Syracuse once again the preeminent power on the island.

In 321 Agathokles received a guest in Syracuse, who had travelled quite far. This guest was no other than a personal friend of the Great King Alexander himself, a man named Harpalos. He had brought with him the enormous sum of 8000 talents of silver. He had tried seeking refuge in Athens, but was rebuffed by the government of Phokion. Harpalos had managed to escape and now sought refuge with Syracuse’s new tyrant. It turned out to be a good gamble, at least for Agathokles, for the ruler of Syracuse was spending money faster than he gained it and with Harpalos’ funds there were no reasons to raise taxes and endanger his popularity. Harpalos was welcomed into the city and shortly afterwards assassinated, his silver seized and his head send east to Alexander, together with a message that the silver was nowhere to be found. Agathokles did not expect Alexander to come west to seek his silver, and by now he started expanding his army even further. Celts, Libyans, Iberians and Italians were all hired, forming a vast mercenary force that should have been capable of finally sweeping the Carthaginians of the island. Plans however changed late in 321, when an envoy from Taras arrived, offering submission to Agathokles if he was able to defend them against the Epirotes. Agathokles, perhaps hoping to prevent another back-and-forth war in Sicily and risk damaging Syracuse itself, decided to take his chance to conquer an Italian empire.

Campaigns of Victory

Year 8, fourth month of the Season of the Inundation, day 20 under the Majesty of the Horus who makes the Two Lands prosperous, He of the Two Ladies who does what the gods desire, the Golden Horus strong-of-arm, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Khakaura, the Son of Ra, Nakhtnebef, ever-living, Beloved by Amun-Ra. His Majesty resided at the fortress at Pelusium when an envoy from Alexander, ruler of the Greeks and the Asiatics came forth from Asia to gaze upon the splendour of His Majesty. The precious goods of Asia were to be exchanged for all the good produce of Egypt, as His Majesty and Alexander desired peace between the Two Lands and Asia. After concluding the negotiations His Majesty went to Iunu and made lavish offerings to his father Ra.

- Egyptian record of the negotiations with Hieronymos of Cardia

The position of Nakhtnebef in 321 was more secure than it had ever been. The alliance with the Argeads had been renewed, albeit through a for the Egyptians unconventional foreign marriage. The pharaoh appeared content for now, having grown his realm and having retained its prosperity. The best recorded event of this year is his participation in the Opet festival at Waset. This was another tradition of the New Kingdom that Nakhtnebef had reinvigorated. It took place just after the start of the Inundation Season, often in July or August. Centred around the temple of Ipet-Resyt (Luxor) it started with a procession of the cult statues of Amun-Ra, Khonsu and Mut from Ipetsut (Karnak) over the processional road to Ipet-Resyt. There ceremonies took place, and at the height of the festival the king communed in private with the supreme god, renewing the Royal Ka and legitimizing his rule. Afterwards both the king and the divine statues proceeded to the riverbank and returned to Ipetsut by boat, while the riverbanks were filled with people hoping to catch a glimpse of either their ruler or the divine statues. During the New Kingdom the festival could take up to 24 days to be completed, but it seems Nakhtnebef’s new version was significantly shorter, perhaps only 2 or 3 days. Besides the official religious ceremonies there was off course also a public festival which attracted a lot of people from all over Egypt. Shortly after the conclusion of the Opet festival however grim news reached the king, Nubia had risen up once again, gold shipments were intercepted and the garrison at Napata was cut off.

Nakhtnebef quickly sailed up the Nile, stopping only in Iunu-Montu to make offerings to the southern war god and in Djeba to make offerings to Horus, and he reached Semna in October 321. At Semna he did not wait for reinforcements to arrive from Egypt but instead marched further south almost immediately, knowing that speed was of the essence and that it still might be possible to catch the enemy off guard. His army was much smaller than the one that conquered Nubia 4 years before, perhaps only 20000 strong, yet these were his elite mercenaries and the regiments of the senenu. The rebels had fortified the isle of Saï in the Nile and hoped to block Nakhtnebef’s advance there, but a daring midnight amphibious assault on the island headed by the king himself managed to capture the island. There are no records of the leaders of the rebellion, and the vassal king of Kush remained loyal, so it seems it was more a spontaneous act against oppression by the Egyptians than a well planned independence struggle. Sadly for the Nubians it was not to be, Nakhtnebef forced his way further south, torching and plundering every village that resisted. At Tabo, just north of Kawa where another Egyptian garrison was entrenched but besieged, the rebels made their stand. Nakhtnebef send half of his forces by ship and landed them behind enemy lines, catching them in a pincer and then had his cavalry, led by Bakenanhur, charge in. The Nubian lines collapsed, Nakhtnebef’s victory was complete. Supposedly up to 50000 men were enslaved, send to the eastern desert to toil in the gold mines, while in the meantime Nakhtnebef marched south to end the war. All resistance melted away and Nakhtnebef reached Napata in March 320, and there erected a stela commemorating his victory. He returned to Egypt in May 320, content knowing that Nubian resistance had been crushed decisively.

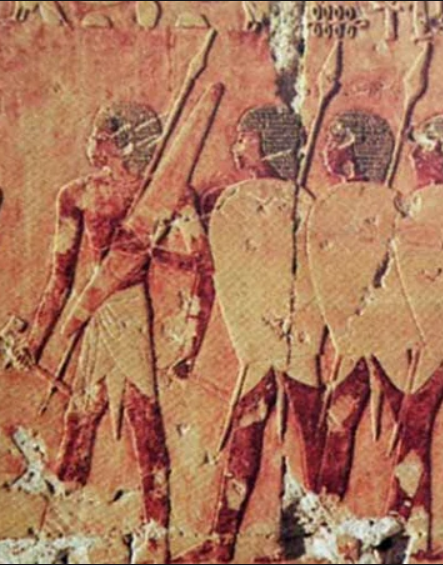

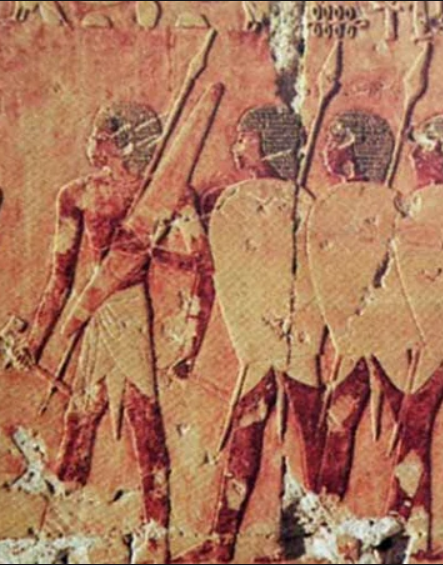

Egyptian soldiers

Returning to Memphis it was not long before the king needed to plan for another campaign. Despite having fortified and garrisoned the various oases in the Western Desert Libyan raiders still managed to bypass the defences, emboldened by the reports of Egyptian prosperity. The damage that was done was minor, and other rulers might have just ignored such a negligible threat. Yet Nakhtnebef, ambitious and warlike, did not. Now that he possessed a sizeable professional force he was determined to use it. But he would not chase after nomads in the desert, at least not personally. His deputy and son-in-law Bakenanhur had managed to corner a group of Libyan raiders near the king’s new coastal settlement at Ineb-Amenti [6] and defeated them, capturing many of them and deporting them to Egypt. Egyptian sources mention that many of the Libyan tribesmen claimed to act not on their own behalf, no they had been bribed to attack Egypt by the Greeks of Cyrene, who were jealous of Egypt’s prosperity. Whether true or not, it looks like just an excuse to attack Cyrene, Nakhtnebef departed Egypt once again in September 320, supported by a fleet of 80 triremes. Cyrene had been independent since Egyptians evicted the Achaemenids, but not much is known about the region during this time. It seems the cities minded their own business, quiet but prosperous.

When confronted with the Egyptian threat the Cyrenians appealed to Alexander, who by this time however was busy with other matters and could not help them. Perhaps he did not want jeopardise his relationship the Egyptians, or perhaps he simply did not care for Cyrene. Desperate, the Cyrenians then applied for help to the sole state on the Hellenic mainland which remained independent, Sparta. It’s independence though was only due to the fact that it no longer could pose a threat to the established Macedonian hegemony. Despite Sparta’s decline it’s Eurypontid king, Eudamidas, decided that it was time for Sparta to once again show its strength and thus departed the city with 500 hoplites, a significant force for the diminished Lacedaemonian state.

Nakhtnebef’s march through the Libyan coastlands went well, all things considered, the various chiefs of the region came to him to offer tribute and men and in return received gold and other luxurious goods. He entered Cyrenaica in October 320, and was confronted by a combined Cyrenian-Spartan force at the promontory at Nausthathmos (OTL modern Ras al-Hillal). Their forces were 8000 strong, and outnumbered by the larger Egyptian force, which numbered 20000. The Spartans and Cretan mercenaries fought well, but the Cyrenians themselves turned out to be inadequate fighters. Eudamidas, who was in command, managed to push back the Egyptian advance with his Spartans but exposed his flank and was assaulted by the Egyptian cavalry. Remarkably he rallied his troops and still managed to stage a retreat, and inflicted substantial casualties on the Egyptian army, which had grown somewhat overconfident thanks to recent victories. Despite that the battle was still an Egyptian victory, and not long afterwards Nakhtnebef received envoys from the cities of Cyrenaica, offering their submission. Not much would change for them, they would stay practically autonomous and would regularly send tribute to Memphis. Nakhtnebef left a small garrison consisting of Greek mercenaries at the region’s most important port at Apollonia-in-Cyrenaica. The pharaoh returned to Egypt in triumph, setting up a victory stela at the Great Temple of Ptah at Memphis and had copies send to be set up at the Temple of Anhur-Shu at Tjebnetjer and at Ipetsut in Waset.

Nakhtnebef could not bask in the glory of his victory for very long, because another rebellion broke out, this time in Philistia, where the cities of Akko and Ashkelon rebelled against the king. Thus in January 319 the king was on the march again, reaching the fortress of Gaza which would function as his base of operations. The reasons behind the rebellion of Akko and Ashkelon are unclear, but according to later sources it had to do with animosity between the Phoenicians and the Philistines over trade routes. Their dispute was to be settled by the pharaoh, who did so in favour of the Phoenicians, thus angering the Philistines. Thankfully for Nakhtnebef no other cities joined in on the rebellion, and his vassals send aid to suppress it. Ashkelon was quickly recaptured and Akko was put under siege in March 319, overland by the Egyptians and their local allies and overseas by the Phoenician fleet. Dwindling supplies and hunger set in quickly, indicating that the rebellion was not particularly well planned or prepared for, and in June 319 the city fell when a traitor opened the gates to the Egyptians. Akko was treated relatively mild, its riches were carted off but the population was not slaughtered wholesale nor sold into slavery. The city’s elite was publicly executed and a garrison was installed in the city, which would be governed by an Egyptian overseer instead of a native oligarchy.

Nakhtnebef enters Akko in triumph

When Nakhtnebef returned to Egypt in 319 he was 39 years old and had been on the throne for almost 10 years, and his reign had been an extraordinary success. Bold and aggressive he seized every opportunity that he saw for expansion, while at home he emphasized ancient traditions, reviving customs from Egypt’s past golden ages and often giving them a new twist. On the back of Egypt’s flourishing economy and influx of gold from the Nubian desert he reformed the army, hoping to establish a professional force loyal only to the crown. On returning from Philistia one of his first visits was to the Temple of Anhur-Shu at Tjebnetjer, where the dynastic tombs were located. His own tomb was already well underway, and Nakhtnebef now commissioned the royal artisans to include a lengthy description of his recent ‘campaigns of victory’, as they were called on the tomb walls. He also ordered them to keep some free space on the walls, where his future accomplishments could be commemorated, he was after all still rather young and could reign on for decades to come. Off course at that moment he could not have known that within a year he would already pass on to the realm of Osiris.

Footnotes

A beardless king

In the third year of the 114th Olympiad, when Archippos was Archon at Athens and when Alexander, son of Philip, had been Great King of Asia for eight years, the King married Nitokris, daughter of the King of Egypt, and afterwards ventured forth from Babylon during the month of Gamelion and with his army waged war on the Cossaeans. They had never been submitted and would not accept a foreign ruler, and they were reviled among the Medes and Persians for their banditry. Eager to prove himself to his subjects and to be the first to subjugate an unconquered people the King left the city for the mountains of Susiana, despite warnings from the Chaldeans that ill omens had been observed.

- Excerpt from The lives of the Great Kings of Asia by Hermocles of Brentesion

Alexander married his new Egyptian wife in November 322, after the return of Hieronymos and his embassy to Babylon. Nitokris was settled together with some courtiers who had travelled with her from Egypt in a wing of the Palace of Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon. Alexander seems to have regarded the marriage as purely political, a sign that the King of Egypt recognized that Alexander was his superior, and it seems that he and Nitokris were never very affectionate. His marriage with Artakama too had been a political ploy, but it seems they at least grew fond of each other. For Nitokris it must have been hard, she spoke barely any Greek and no Persian or Aramaic, and was rather isolated outside of her small circle of Egyptian courtiers. Arrangements were made however to make her feel at home, including the construction of a small shrine to Isis at the palace.

For Alexander’s subjects, both Persian and Macedonian, his second marriage was another affirmation of his traditional kingship, for both peoples were used to their rulers being polygamous. This was important, for in many ways Alexander was an atypical king, for both the Macedonians and the Persians. Starting with his very appearance; on all his portraits he appears beardless, with long flowing hair and an upwards gaze and always youthful, a far cry from the stern bearded rulers that preceded him in both Persia and Macedon. The men of his generation, like Ptolemaios, Seleukos and Lysimachos, followed their king’s example and also were clean shaven. It mostly spread among the Macedonian nobility, the Persians and other easterners seemed to have mostly kept their beards. He also attempted to somewhat syncretize the outward image of both monarchies. Alexander adopted the white robes of the Persian monarchy, but rejected the tiara, instead of which he wore the Hellenic diadem, a broad purple silk ribbon ending in a knot which surrounded the king’s head. Among the Hellenes it was also used to crown victorious athletes, giving Alexander an explicit connection to Hellenic traditions and victory itself.

Victory too was what Alexander hoped to achieve when he left Babylon in January 321, leading 20000 men against the Cossaeans, a people who lived north of Susiana and were never subjugated by the Achaemenids. Like the Uxians they controlled mountain passes and started raiding trade caravans when the Macedonians decided not to pay them off. It was supposed to be a short and victorious campaign but it turned out to be quite hazardous. Marching up the Eulaios it was near the upper reaches of that river that the army’s vanguard was ambushed. Alexander, who led the vanguard, rallied his bodyguard and charged into the Cossaean lines, forcing them back and allowing the rest of his troops to regroup. This they did, but during the charge Alexander was hit in his shoulder by a javelin, after which he fell from his horse. The bodyguard fell back and defended their king, and when the Macedonian main force arrived the Cossaeans were decisively routed. Alexander, despite his wounds, continued leading the campaign. The Cossaeans were granted no mercy, and after three months of campaigning Alexander had decimated them, destroying their strongholds and forcing them out of the mountains. Alexander returned to Babylon in April 321, after another brutal campaign.

Bust of Alexander, with his usual youthful appearance

Despite the relative unimportance of the campaign it had big consequences for Alexander himself, who for the rest of his life suffered from pain in his right shoulder, where he was hit by the javelin. It did not impair him at first, but later on in his life he would no longer fight in the front lines due to the pain and stiffness of his shoulder. For now however Alexander could still lead his armies and soon after returning to Babylon he already readied his forces for the next campaign. In June 321 Alexander was in Herakleia-on-the-Tigris (OTL Charax) where under the supervision of his admiral Nearchos a fleet had been constructed, consisting of 30 quadriremes and 90 triremes, meant for the subjugation of the lands on the Arabian coasts of the Persian Gulf. Gerrha, located on the south coast of the gulf and an important centre of trade with India overseas and Southern Arabia via the caravan routes, was the King’s first target. The Gerrhaeans must have been aware of who they were dealing with, and wisely did not resist and offered their submission when the royal fleet appeared, the city’s rulers accepted a garrison and agreed to pay tribute to Alexander. Afterwards the fleet went onwards to Tylos (Bahrain), an island in the gulf that was the centre of the pearl trade. A small show of force was all what was needed to convince the Tylians that resistance was futile, and Alexander, seeing the potential of the isle as a centre of trade, founded a city on the island which he named Alexandria-on-Tylos, but which came to be known just as Tylos.

The Great King stayed on the island for two months, receiving envoys from nearby communities and overseeing the arrival of the first Greek settlers. After personally marking the boundaries of his new city the King left Tylos and sailed east alongside the coast with his fleet, not encountering any large settlements until he reached a city on the coast in the region that was the former Achaemenid satrapy of Maka, he disembarked with his army and quickly accepted the surrender of the locals. What they named their hometown is unknown, but Alexander renamed it to Apollonia [1]. The city was an important trade centre for a city further inland, known to the Hellenes as Mileia [2] and not long after Alexander’s conquest a messenger arrived from the ruler of Mileia demanding that the invaders leave. This off course only aggravated the Great King of Asia, who send the Mileian ruler, a man named Melichos in the Greek sources, an ultimatum: either submit and be spared or resist and be destroyed. No reply came, and thus Alexander marched inland with a picked force, 12000 strong, a relatively small force were he campaigning in India but here in Arabia it was a vast army, which no local ruler could hope to match.

The march to Mileia was gruelling, but Alexander was well-prepared, aware as he was of the desert conditions of the area camels were brought along from Persia for transport of supplies and water. Most of the locals also turned out to be quite willing to supply Alexander’s army with water and food. Around the end of September 321 he reached the vicinity of Mileia, where he was confronted by Melichos, who decided to gamble everything on a clash on the open field instead of a siege. Sadly for him his troops were no match for Alexander’s crack troops, who easily routed the Arabs. Mileia fell after a short siege, Melichos was captured and crucified for his attempt at resisting the Argeads. Alexander left behind a small garrison, consisting of his most recalcitrant troops, in Mileia and returned to Apollonia. There he made offerings to Zeus and had a shrine constructed to him. Maka would be an independent satrapy with Apollonia as its capital, but Argead control never reached far beyond the walls of that city, with the more inland communities practically independent and only occasionally sending tribute to the city. Laomedon of Mytilene, a personal friend of the King and brother of the satrap of Ariana Erigyius, was made satrap of Maka. It does not appear to have been a demanding job, for despite staying satrap of Maka for the rest of his life we often find Laomedon at the court in Babylon, indicating that most of the work was done by his deputies.

Leaving Apollonia behind Alexander and the fleet proceeded onward towards the city of Omana (Sohar in Oman), also located on the coast east of Mileia and a centre of copper production. Perhaps they had heard of the grim fate of Melichos and his compatriots, or they were aware of the reputation of the Great King, but as soon as the fleet appeared before the city envoys were send by the rulers of the city who offered their subjugation to Alexander. He accepted, and Omana and its environs would also become part of the satrapy of Maka, giving the Argeads at least nominally the control over the entire Persian Gulf. Harmozeia (Hormuz) in Carmania was Alexander’s next port of call. Carmania had been a somewhat troubled satrapy, Philip had left it’s satrap Aspastes in place and so did Alexander, but during Alexander’s Indian campaign Aspastes had tried to launch a rebellion, but his attempt was crushed by Philotas. Philotas had, probably after consulting with Alexander, appointed Kleandros, brother of Koinos, as satrap of Carmania. While in Harmozeia however Alexander received several local delegations, all of whom derided Kleandros as a cruel and merciless tyrant. He had been corrupt and even sacrilegious, forbidding the Iranians from exposing their dead to the elements as is usual in the Zoroastrian tradition. Alexander had Kleandros removed from his post and executed, probably more for his corruption than anything else, but to the Iranians it must have seemed as if the Great King was willing to protect them too. There were some murmurs of discontent among the Macedonian nobility, but no open hostility, they too knew that corruption and cruelty could not be abided by their king. Koinos, who had been so crucial during the campaigns in Sogdiana and India, was appointed as his brother’s replacement in Carmania, a slightly puzzling choice, but perhaps Alexander wanted to give Koinos a chance to redeem the family name.

Alexander returned to Babylon via Persepolis in December 321. His campaign had been a great success, he had managed to consolidate his control over the Persian Gulf and the maritime route to India, increasing trade and prosperity in the region. For several months he remained in the city, receiving envoys, settling disputes, presiding over festivals and other kingly duties. The more tedious tasks of government he left to the chiliarch Antigonos and to Eumenes. For now it seemed the empire Alexander and his father had built was doing well, their far-reaching conquests had united various peoples and their lands, opening up new trade routes and opportunities. The treasury of the empire was healthy, despite a tendency by Alexander to grant lavish gifts of gold and silver to those he favoured. Taxing the population and trade, plunder from campaigns and the revenue from the mines and forests of the empire, who stood under direct state control, all ensured that Alexander was the world’s richest man by a fair margin. The government of the empire however was a delicate balancing act on Alexander’s part. On one hand he had to placate the Macedonians, who still formed the professional core of his army and who expected their king, who was after all first and foremost the king of Macedonia, to treat them preferentially. On the other hand were the Asian inhabitants of the empire, primarily the Persians and Medes, but the Babylonians, Syrians, Sogdians and Indians were important too. For them Alexander tried, and mostly succeeded, to play the role of rightful Great King of Asia and heir to the Achaemenid dynasty.

The gargantuan resources that were at his disposal enabled Alexander to embark upon several building and infrastructural projects. The Palace of Nebuchadnezzar at Babylon was renovated, adding a distinct Hellenic flair to the building. Babylon’s Hellenic district, known as the Philippeion, also saw the construction of a large theatre and a temple to Artemis, both sponsored by the Great King himself. The city’s harbour on the Euphrates was also expanded, making it possible to accommodate larger ships and thus making trade via the river more convenient. These were however small projects in comparison with the wholesale construction of cities elsewhere in Mesopotamia, Syria and the Upper Satrapies [3]. These cities, planned in a grid pattern and mostly settled by Alexander’s veterans and immigrants from the Aegean, would be the backbone of Argead rule in the Near East.

Alexander did not stay in Babylon for very long, restless as he often was. Already he was planning new military campaigns, first he would subjugate the south coast of the Black Sea and then he would launch a pincer attack on the Caucasus, he himself would march in from the west while Krateros and Philotas would charge in from Media and Armenia respectively. Just before the start of the campaign Peukestas was send east to Arachosia with 15000 men, including a large force of Persian phalangites, to help supressing a revolt there. Peukestas was a natural fit to lead a mixed force, being one of the few Macedonians who were genuinely interested in Persian culture he even learned to speak their language. Alexander himself set off in March 320, marching up the Euphrates and through Syria, where he inspected the new city of Nikatoris-on-the-Orontes. The construction works in Nikatoris had not gone well, and the person who was in charge of it, a childhood friend of the King named Harpalos, had seemingly vanished into thin air with funds meant for construction of the city not long before the King’s arrival. While in Nikatoris a delegation arrived from Epiros, send by his mother; requesting aid from the Great King. For a short while it seems the King hesitated, but in the end he relented. News had also reached him of unrest in Macedon and Greece, and perhaps he was eager to see Hephaistion again after many years. Whatever the case the Caucasus campaign was abandoned for now, instead the Great King of Asia would march west.

Western affairs

Were we to consider what was the greatest city of the Hellenes at the time of Alexander than we can safely ignore Sparta, defeated and dejected, or Athens, proud but subjugated. Neither are it the brave Boeotians, the men of Thebes, or the Corinthians, powerless before Alexander’s men on the Acrocorinth. No, it is to Sicily, to they who drink the waters of Arethusa, majestic Syracuse, greatest polis of the Hellenes, that we must look.

- Excerpt from Antikles of Massalia’s History of the Hellenes vol. 3: from Philippos Nikator to the Polemarcheia

When Alexander of Epiros left the Italian peninsula in 331 BCE he left behind a garrison in the city of Taras, to safeguard it against the encroaching Saunitai (Samnites). When he died several years later his widow Cleopatra became regent for the boy king Neoptolemos II and was backed up by a Macedonian army under Leonnatos and the authority of her own mother Olympias. With Epiros now more or less a Macedonian vassal Taras became the most western outpost of an empire stretching to the foothills of the Himalaya. While the Saunitai were still a threat the Tarentines remained docile, and on one occasion Leonnatos himself crossed the Adriatic with a combined Macedonian-Epirote force and defeated Saunitai raiders who threatened the city. By the late 320’s however the situation had changed. The city of Rome, the greatest power of the middle of the peninsula and chief city of the Latins, expanded it sphere of influence southwards, to the fertile plains of Campania, which were also coveted by the Saunitai. Conflict broke out between the two, and for several years the hills of southern Italia were drenched with blood. It was a merciless conflict, exemplified by the fact that that one point the Saunitai managed to trap a Roman army in the valley of Caudine Forks and massacred them completely. The war dragged on, and the pressure that the Saunitai exerted on the Greek cities of Megale Hellas, including Taras, diminished.

Thus the Tarentines in 321, eager to finally be rid of the Epirotes and their Macedonian masters, evicted the garrison. While they were entrenched in a fortress either by treachery or bribery it fell, and the soldiers were either massacred or sold into slavery. The Tarentines calculated that the Epirotes might have had something better to do, and in this they were partially right for the Illyrians were once again becoming a problem, raiding coastlines and terrorizing traders in the Adriatic. Yet Tarentine treachery would not be forgiven nor forgotten by Olympias and Cleopatra, who requested aid from Hephaistion, who complied and send them some forces. The Epirote army, trained in the Macedonian way of war, complemented with Hephaistion’s forces, was a potent force. When the Tarantines noticed that the Epirotes would not relent and that they would be up against the might of Macedonia itself they attempted to form a defensive league with the other cities of Megale Hellas, as they had done in the past to see off threats. Now however the other cities of Megale Hellas, such as Kroton, Rhegion and Herakleia decided to ignore Taras’ pleas for help. Desperate for allies, Taras thus turned to the western Hellenes’ greatest city for aid, hoping that its new and unpredictable ruler would be willing to help them.

Agathokles

Syracuse’s history in the preceding century had been one of ups and downs. Under Dionysius I, a ruthless tyrant whose professional mercenary army and state apparatus might be seen as a precursor to Alexander and Philip, it had reached the zenith of its power. It had almost driven the Carthaginians [4] of the island and had expanded its sphere of influence in Megale Hellas. Dionysius I was seen as cruel and vindictive, yet also a patron of artists and philosophers. His son Dionysius II however was less than capable and ousted in a coup, although later on he would regain his throne only to be overthrown once again. In 343 Timoleon, originally from Syracuse’s mother city of Corinth, managed to take control of the city and installed a democratic government. His most famous act was the defeat of the Carthaginians at the river Crimissus in 339. After Timoleon’s death Syracuse once again fell into bloody civil strife and factionalism. An oligarchy was established, but Syracuse was still rather unstable. The situation came ahead in 322 BC, when Agathokles [5], a military man with a knack for populism gathered a mercenary force and managed to overthrow the oligarchic regime. He announced the formal restoration of democracy, but by merit of his sizeable army he practically was the new tyrant. Making use of his army he captured Akragas and Gela, making Syracuse once again the preeminent power on the island.

In 321 Agathokles received a guest in Syracuse, who had travelled quite far. This guest was no other than a personal friend of the Great King Alexander himself, a man named Harpalos. He had brought with him the enormous sum of 8000 talents of silver. He had tried seeking refuge in Athens, but was rebuffed by the government of Phokion. Harpalos had managed to escape and now sought refuge with Syracuse’s new tyrant. It turned out to be a good gamble, at least for Agathokles, for the ruler of Syracuse was spending money faster than he gained it and with Harpalos’ funds there were no reasons to raise taxes and endanger his popularity. Harpalos was welcomed into the city and shortly afterwards assassinated, his silver seized and his head send east to Alexander, together with a message that the silver was nowhere to be found. Agathokles did not expect Alexander to come west to seek his silver, and by now he started expanding his army even further. Celts, Libyans, Iberians and Italians were all hired, forming a vast mercenary force that should have been capable of finally sweeping the Carthaginians of the island. Plans however changed late in 321, when an envoy from Taras arrived, offering submission to Agathokles if he was able to defend them against the Epirotes. Agathokles, perhaps hoping to prevent another back-and-forth war in Sicily and risk damaging Syracuse itself, decided to take his chance to conquer an Italian empire.

Campaigns of Victory

Year 8, fourth month of the Season of the Inundation, day 20 under the Majesty of the Horus who makes the Two Lands prosperous, He of the Two Ladies who does what the gods desire, the Golden Horus strong-of-arm, the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Khakaura, the Son of Ra, Nakhtnebef, ever-living, Beloved by Amun-Ra. His Majesty resided at the fortress at Pelusium when an envoy from Alexander, ruler of the Greeks and the Asiatics came forth from Asia to gaze upon the splendour of His Majesty. The precious goods of Asia were to be exchanged for all the good produce of Egypt, as His Majesty and Alexander desired peace between the Two Lands and Asia. After concluding the negotiations His Majesty went to Iunu and made lavish offerings to his father Ra.

- Egyptian record of the negotiations with Hieronymos of Cardia

The position of Nakhtnebef in 321 was more secure than it had ever been. The alliance with the Argeads had been renewed, albeit through a for the Egyptians unconventional foreign marriage. The pharaoh appeared content for now, having grown his realm and having retained its prosperity. The best recorded event of this year is his participation in the Opet festival at Waset. This was another tradition of the New Kingdom that Nakhtnebef had reinvigorated. It took place just after the start of the Inundation Season, often in July or August. Centred around the temple of Ipet-Resyt (Luxor) it started with a procession of the cult statues of Amun-Ra, Khonsu and Mut from Ipetsut (Karnak) over the processional road to Ipet-Resyt. There ceremonies took place, and at the height of the festival the king communed in private with the supreme god, renewing the Royal Ka and legitimizing his rule. Afterwards both the king and the divine statues proceeded to the riverbank and returned to Ipetsut by boat, while the riverbanks were filled with people hoping to catch a glimpse of either their ruler or the divine statues. During the New Kingdom the festival could take up to 24 days to be completed, but it seems Nakhtnebef’s new version was significantly shorter, perhaps only 2 or 3 days. Besides the official religious ceremonies there was off course also a public festival which attracted a lot of people from all over Egypt. Shortly after the conclusion of the Opet festival however grim news reached the king, Nubia had risen up once again, gold shipments were intercepted and the garrison at Napata was cut off.

Nakhtnebef quickly sailed up the Nile, stopping only in Iunu-Montu to make offerings to the southern war god and in Djeba to make offerings to Horus, and he reached Semna in October 321. At Semna he did not wait for reinforcements to arrive from Egypt but instead marched further south almost immediately, knowing that speed was of the essence and that it still might be possible to catch the enemy off guard. His army was much smaller than the one that conquered Nubia 4 years before, perhaps only 20000 strong, yet these were his elite mercenaries and the regiments of the senenu. The rebels had fortified the isle of Saï in the Nile and hoped to block Nakhtnebef’s advance there, but a daring midnight amphibious assault on the island headed by the king himself managed to capture the island. There are no records of the leaders of the rebellion, and the vassal king of Kush remained loyal, so it seems it was more a spontaneous act against oppression by the Egyptians than a well planned independence struggle. Sadly for the Nubians it was not to be, Nakhtnebef forced his way further south, torching and plundering every village that resisted. At Tabo, just north of Kawa where another Egyptian garrison was entrenched but besieged, the rebels made their stand. Nakhtnebef send half of his forces by ship and landed them behind enemy lines, catching them in a pincer and then had his cavalry, led by Bakenanhur, charge in. The Nubian lines collapsed, Nakhtnebef’s victory was complete. Supposedly up to 50000 men were enslaved, send to the eastern desert to toil in the gold mines, while in the meantime Nakhtnebef marched south to end the war. All resistance melted away and Nakhtnebef reached Napata in March 320, and there erected a stela commemorating his victory. He returned to Egypt in May 320, content knowing that Nubian resistance had been crushed decisively.

Egyptian soldiers

Returning to Memphis it was not long before the king needed to plan for another campaign. Despite having fortified and garrisoned the various oases in the Western Desert Libyan raiders still managed to bypass the defences, emboldened by the reports of Egyptian prosperity. The damage that was done was minor, and other rulers might have just ignored such a negligible threat. Yet Nakhtnebef, ambitious and warlike, did not. Now that he possessed a sizeable professional force he was determined to use it. But he would not chase after nomads in the desert, at least not personally. His deputy and son-in-law Bakenanhur had managed to corner a group of Libyan raiders near the king’s new coastal settlement at Ineb-Amenti [6] and defeated them, capturing many of them and deporting them to Egypt. Egyptian sources mention that many of the Libyan tribesmen claimed to act not on their own behalf, no they had been bribed to attack Egypt by the Greeks of Cyrene, who were jealous of Egypt’s prosperity. Whether true or not, it looks like just an excuse to attack Cyrene, Nakhtnebef departed Egypt once again in September 320, supported by a fleet of 80 triremes. Cyrene had been independent since Egyptians evicted the Achaemenids, but not much is known about the region during this time. It seems the cities minded their own business, quiet but prosperous.

When confronted with the Egyptian threat the Cyrenians appealed to Alexander, who by this time however was busy with other matters and could not help them. Perhaps he did not want jeopardise his relationship the Egyptians, or perhaps he simply did not care for Cyrene. Desperate, the Cyrenians then applied for help to the sole state on the Hellenic mainland which remained independent, Sparta. It’s independence though was only due to the fact that it no longer could pose a threat to the established Macedonian hegemony. Despite Sparta’s decline it’s Eurypontid king, Eudamidas, decided that it was time for Sparta to once again show its strength and thus departed the city with 500 hoplites, a significant force for the diminished Lacedaemonian state.

Nakhtnebef’s march through the Libyan coastlands went well, all things considered, the various chiefs of the region came to him to offer tribute and men and in return received gold and other luxurious goods. He entered Cyrenaica in October 320, and was confronted by a combined Cyrenian-Spartan force at the promontory at Nausthathmos (OTL modern Ras al-Hillal). Their forces were 8000 strong, and outnumbered by the larger Egyptian force, which numbered 20000. The Spartans and Cretan mercenaries fought well, but the Cyrenians themselves turned out to be inadequate fighters. Eudamidas, who was in command, managed to push back the Egyptian advance with his Spartans but exposed his flank and was assaulted by the Egyptian cavalry. Remarkably he rallied his troops and still managed to stage a retreat, and inflicted substantial casualties on the Egyptian army, which had grown somewhat overconfident thanks to recent victories. Despite that the battle was still an Egyptian victory, and not long afterwards Nakhtnebef received envoys from the cities of Cyrenaica, offering their submission. Not much would change for them, they would stay practically autonomous and would regularly send tribute to Memphis. Nakhtnebef left a small garrison consisting of Greek mercenaries at the region’s most important port at Apollonia-in-Cyrenaica. The pharaoh returned to Egypt in triumph, setting up a victory stela at the Great Temple of Ptah at Memphis and had copies send to be set up at the Temple of Anhur-Shu at Tjebnetjer and at Ipetsut in Waset.

Nakhtnebef could not bask in the glory of his victory for very long, because another rebellion broke out, this time in Philistia, where the cities of Akko and Ashkelon rebelled against the king. Thus in January 319 the king was on the march again, reaching the fortress of Gaza which would function as his base of operations. The reasons behind the rebellion of Akko and Ashkelon are unclear, but according to later sources it had to do with animosity between the Phoenicians and the Philistines over trade routes. Their dispute was to be settled by the pharaoh, who did so in favour of the Phoenicians, thus angering the Philistines. Thankfully for Nakhtnebef no other cities joined in on the rebellion, and his vassals send aid to suppress it. Ashkelon was quickly recaptured and Akko was put under siege in March 319, overland by the Egyptians and their local allies and overseas by the Phoenician fleet. Dwindling supplies and hunger set in quickly, indicating that the rebellion was not particularly well planned or prepared for, and in June 319 the city fell when a traitor opened the gates to the Egyptians. Akko was treated relatively mild, its riches were carted off but the population was not slaughtered wholesale nor sold into slavery. The city’s elite was publicly executed and a garrison was installed in the city, which would be governed by an Egyptian overseer instead of a native oligarchy.

Nakhtnebef enters Akko in triumph

When Nakhtnebef returned to Egypt in 319 he was 39 years old and had been on the throne for almost 10 years, and his reign had been an extraordinary success. Bold and aggressive he seized every opportunity that he saw for expansion, while at home he emphasized ancient traditions, reviving customs from Egypt’s past golden ages and often giving them a new twist. On the back of Egypt’s flourishing economy and influx of gold from the Nubian desert he reformed the army, hoping to establish a professional force loyal only to the crown. On returning from Philistia one of his first visits was to the Temple of Anhur-Shu at Tjebnetjer, where the dynastic tombs were located. His own tomb was already well underway, and Nakhtnebef now commissioned the royal artisans to include a lengthy description of his recent ‘campaigns of victory’, as they were called on the tomb walls. He also ordered them to keep some free space on the walls, where his future accomplishments could be commemorated, he was after all still rather young and could reign on for decades to come. Off course at that moment he could not have known that within a year he would already pass on to the realm of Osiris.

Footnotes

- The OTL archaeological site of Ed-Dur in the UAE.

- The archaeological site of Mleiha in the UAE which flourished around this time, it is not known what its name was, so I more or less Hellenised its current name, I hope that isn’t too much of a problem.

- TTL, as in OTL, this refers to the satrapies east of the Zagros.

- I know it is not very consistent, but I’ll refer to Carthage as Carthage and not as Karkhedon or Qart-Hadasht and its inhabitants as the Carthaginians.

- OTL he managed to come to power in 317, but he was exiled before because he tried overthrowing the government, he just succeeds earlier here.

- See update 11, OTL site of Paraetonium

Last edited: