The Grant Assassination

On the evening of April 14th, 1865 President Lincoln and the First Lady attended the play Our American Cousin, just five days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. Also in attendance was General Ulysses S. Grant, who went ahead with his plan to join the President despite a desire to visit his children in New Jersey.

At 10:14 pm, John Wilkes Booth entered the back of the Presidential box, and as he prepared to draw his gun Booth was spotted by Grant who tackles the assassin to the floor. In the struggle, Grant was shot in the chest while grappling for Booth's derringer. As Booth attempted to flee he was captured by Major Henry Rathbone. General Grant was then taken across the street to the Petersen House where doctor Charles Leale, Charles Sabin Taft, and Albert Freeman Africanus King, Lincoln pronounced Grant dead several hours later.

After being flogged by Union Army officers for several hours, Booth confessed to being a member of the Knights of the Golden Circle and revealed the identities of Lewis Powell (who was assigned to kill Secretary of State William H. Seward at his home), George Atzerodt (who was to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson at the Kirkwood Hotel), and David E. Herold as fellow conspirators.

The Assassination of General Grant, and the discovery of Booth's ties to the Confederacy shocked the nation, and forced Lincoln to reassess his plans for Reconstruction. Secretary of War Edward M. Stanton and Attorney General James Speed pushed Lincoln to broaden the scope of the trial of the conspirators. Lincoln ultimately decided to try Booth and his associates in a civilian court, but ordered Secretary of Stanton to proceed with rounding up Confederate leaders for arrest and trial for high treason. On September 30th, 1865 the Fort McNair Trials began, and over the course of 13 months the military tribunal found guilty and hanged most of the Confederate leadership, including Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. While the trial was being carried out, a separate legal battle was brought before the courts by southern lawyers seeking to save their leaders from the gallows, hoping that by establishing the legality of secession, the Confederate leadership could then not be convicted. The court ultimately ruled that Secession was unconstitutional.

The execution of the Confederate leaders, and Lincoln's decision to uphold General Sherman's Special Field Orders No. 15, gave rise to militant groups like the Ku Klux Klan, which attempted to raid patrols of occupying Union troops, capture arms, and ultimately restart the war. Lincoln leaned heavily on his Commanding General of the Army,

William Tecumseh Sherman to stamp out the "Lost Cause" movement, and those close to the President remark on the weariness at which he approached each day, and relied more and more on Sherman. Just three years after leaving office Abraham Lincoln died of a stroke at the age of 63.

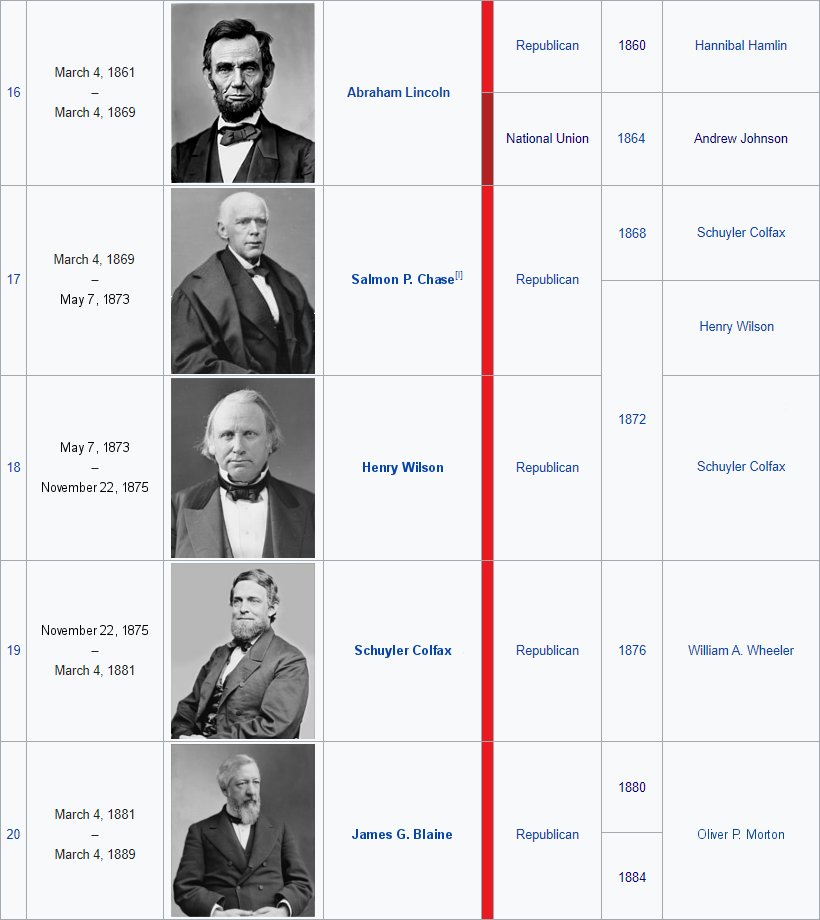

Shortly after the Inauguration Day celebrations of 1869, a group of neo-confederate troops attempted to take control of a US Army armor in Texas shortly before its readmission to the Union. The failed attack on Tyler Arsenal ultimately spelled the end for the Neo-Confederate movement, as it prompted Congress to push through the Third Enforcement Act which empowered President Salmon P. Chase to suspend the writ of habeas corpus to combat Neo-Confederate and white supremacy organizations.

Last edited: