I’m sure it’ll be great!Okay, so I can with total certainty say that the next chapter will be posted tomorrow. We can just pretend I posted it today, it'll be our little secret.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Give Peace Another Chance: The Presidency of Eugene McCarthy

- Thread starter The Lethargic Lett

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 20 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Six - Fortunate Son The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour: Its Origins and Near-Death Chapter Seven - Medley: Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In (The Flesh Failures) The Decline of the Hippie and the Rise of the Cleagie: Woodstock, Manson, and Altamont Chapter Eight - We've Only Just Begun The 1970 Midterm Election Results Chapter Nine – Bangla Dhun Ah, After 10,000 Years I'm Free!

Chapter Nine – Bangla Dhun

Chapter Nine – Bangla Dhun

A semblance of peace had finally come to Vietnam with the election of the communist fellow traveller Trần Văn Hữu as President of South Vietnam and the deposition of Lê Duẩn by Trường Chinh for the title of General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam. Likewise, peace had come to Laos after royalist forces were compelled into forming a coalition government with the communist Panthet Lao and their leader, Prince Souphanouvong, in the midst of American military withdrawal. However, the events of the early 1970s proved that Asia would remain wracked by conflict even without American help.

Like South Vietnam and Laos, the neutralist regime of Chief of State (and former King) Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia had entered into a coalition with communists. However, unlike the former two, Sihanouk had done so years earlier, and had them purged from the government completely in 1968. Since then, Sihanouk's political organization Sangkum had been dominated by right wing elements, led by Prime Minister Lon Nol. However, for his tolerance of North Vietnamese troops crossing his territory, Sihanouk was still considered an ally of communism by the international socialist fraternity. Because of this, Cambodia's communists either fled to North Vietnam, or aligned with the rural guerillas of Saloth Sâr, one of the country's most radical communists who had refused to work with Sihanouk from the start.

After years of supporting the rightist elements within Sihanouk's regime, the United States' last act before withdrawing completely from his country was to warn him of a coup by those very same rightist elements. Besides being prime minister, Lon Nol was also the leader of the armed forces. Frustrated with Sihanouk's tolerance of the Vietnamese communists, Lon Nol intended to use anti-Vietnamese sentiments to whip up a riot, then launch a soft coup to compel Sihanouk to cut all ties with North Vietnam. However, Lon Nol's co-conspirator, Deputy Prime Minister Sisowath Sirik Matak, wanted to remove Sihanouk completely, abolish the monarchy, and install a republican military dictatorship. Needing the tacit approval of the CIA mission in the country either way, the plotters informed them of the plan. But, rather than supporting the coup, the CIA informed Sihanouk of the plan, on the orders of President McCarthy and Director of the CIA Thomas McCoy. Using loyalists in the police under the control of his brother-in-law, Secretary of State for Defence Oum Mannorine, Sihanouk had the plotters arrested in early 1970. In the ensuing purge, Sihanouk put much of the military's duties in the hands of the police. Both military loyalists to Lon Nol and Sirik Matak's clique in the National Assembly were rounded up and put under arrest. With the military leadership and Sirik Matak clique removed from office and the leftists having been exiled years ago, Sihanouk's government became entirely reliant on the liberal democratic centre led by the parliamentarian In Tam [1].

The aftermath of the failed coup left Cambodia divided between two powers that were both divided amongst themselves. The Sangkum government was split between Sihanouk's autocratic loyalists and In Tam's parliamentary liberals in an incredibly fragile government but one with no real opposition. The communists were split between Saloth Sâr's Communist Party of Kampuchea (Nationalist), which refused to cooperate with any other group and continued guerrilla action against Sihanouk, and Son Ngoc Minh's Communist Party of Kampuchea (Internationalist). A longtime ally of the Vietnamese communist movement, the elderly Son Ngoc Minh was selected by the North Vietnamese as a cooperative, relatively moderate alternative compared to Saloth Sâr. Rather than direct confrontation, the Internationalists instead followed Trường Chinh's policy of building grassroots support and taking power through political means, or at least until a united Vietnam could install them into power. Tensions would become so fierce between the two communist camps that the North Vietnamese attempted to assassinate Saloth Sâr at what was supposed to be a joint operational security negotiation, permanently dividing the two communist factions [2].

Cambodia's prime minister and leading general, Lon Nol (centre), was arrested and later executed after he was uncovered plotting a right wing coup against Chief of State Norodom Sihanouk. The subsequent purge of conservative elements in the Cambodian government left Sihanouk entirely reliant on the liberal democratic centrists in the National Assembly.

While conflict was winding down to the east, the next great crisis in Asia would emerge in Pakistan, where election interference and ethnic conflict threatened to rip the country in half.

Pakistan, as a nation, had its roots in Muslim intellectual circles of the late 19th Century and early-to-mid 20th Century. Living under the rule of the British Raj, members of the Muslim upper middle class believed that Westernization through accepting British-style education and bureaucratic methods would be the only way to stay politically relevant. To that end, they formed the All-India Muslim League (AIML) in 1906, in part as a counter to the older and larger Indian National Congress (INC). The AIML’s long-time leader, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, believed that the INC was dominated by Hindus, and that if India were to become one country a Hindu governing elite would marginalize the Muslim population. As a solution, Jinnah became a leading advocate of two-nations theory: the idea that Hindus and Muslims were too culturally different to ever peacefully coexist, and that the best solution would be a partition into two nations, one Muslim, and one Hindu. The AIML also advocated for cooperation with British colonial authorities and ‘working inside the system’ to meet their goals. This was all in contrast to the INC. Advocating an inclusive nationalism of all Indian ethnicities and creeds, the INC believed in a single indivisible Indian nation, and followed a line of civil unrest, peaceful protests, and non-co-operation made famous by Mohandas Gandhi, who, while only formally serving a short term as the INC’s president, was acknowledged as the organization’s premier leader for decades. Following highly divided election results in 1945 and 1946 (with the AIML winning overwhelmingly in Muslim areas and the INC winning overwhelmingly everywhere else), the British agreed to arbitrate a partition along the lines of two-nations theory, overseen by the last Viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten. In most cases, provinces with a clear majority were awarded to either India or Pakistan, but in two cases, provinces with a sizeable Muslim minority were also partitioned, with the Muslim portions being allocated to Pakistan. Such was the case in West Punjab and East Bengal. The princely states – parts of the British Raj ruled by various kings which had been technically independent under colonial rule – were also pressured into joining either India or Pakistan. However, problems emerged in princely states who had a ruler of one religion but a majority population of the other. This issue was most pronounced in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, to the far north of the former colony, and on the border between India and Pakistan. Although it had a Muslim majority, Jammu and Kashmir’s ruler, the Maharajah Hari Singh, was Hindu. Initially attempting to maintain his independence, Singh eventually agreed to join his state to India, after his army was defeated by Muslim tribal militias from Pakistan looking to forcibly annex his realm [3]. This triggered an inconclusive war between the two newly independent countries in 1947, which left Jammu and Kashmir divided between the two of them, and with the battle line acting as the de facto border. While the centre of conflict, the partition of India also led to widespread sectarian violence, massive riots, paramilitary skirmishes, and the largest mass migration in human history. Both Gandhi and Jinnah would die before the war’s end in 1949. The former was killed by a Hindu supremacist who believed he was coddling the religious minorities (especially the Muslims), while the latter died of tuberculosis after becoming the first Governor General of Pakistan.

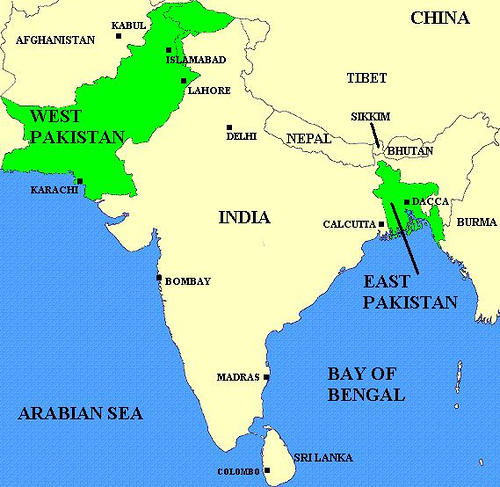

Once it achieved its independence, Pakistan was notably the world’s only exclave country, meaning its territory did not geographically connect. While ‘mainland’ Pakistan was on the northwestern border of India, East Bengal, which contained most of Pakistan’s population, was far to the east, on the other side of the subcontinent. West Pakistan’s political dominance would remain a sticking point in the country that would eventually lead to war in 1971.

Following the First Indo-Pakistani War and an attempted coup by communists in the military, Pakistan’s first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, was assassinated, and Jinnah’s successor as governor general, Khawaja Nazimuddin, took his place. Despite being Bengali himself, Nazimuddin was unable to cope with widespread protests in East Bengal that demanded that the Bengali language be recognized as an official language of Pakistan along with Urdu, the most common language of the western provinces. On top of that, riots in the freshly partitioned province of Punjab continued despite Nazimuddin invoking martial law, and he was dismissed by the governor general for failing to restore order. Next was Mohammad Ali Bogra. Bogra looked to stabilize the relationship with East Bengal by reforming Pakistan’s provincial borders. East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan, while the four western provinces – Khyber Pakhtunkwah, Punjab, Balochistan, and Sindh – were merged into one province called West Pakistan. Bogra also made preparations to change Pakistan’s constitution from a British dominion to a fully independence republic that enshrined Islam into the legal system, and pursued closer relations with the United States and the People’s Republic of China. However, Bogra was dismissed by Governor General Iskander Ali Mizra after his party, the Muslim League (the official successor to the AIML), placed fourth in the 1954 East Bengal legislative election. After the passage of the new constitution, the country officially became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, a semi-presidential parliamentary democracy, with Mizra appointed its first president by an electoral college. With no prime minister able to hold together a workable governing coalition and with a nationwide election yet to be held, Mizra continuously sacked his own heads of government. With it looking unlikely that he would win re-election, Mizra declared martial law, and dissolved his own party’s government, resulting in General Muhammad Ayun Khan launching a coup, appointing himself president and military dictator, and leaving the office of prime minister intentionally vacant. Under his rule, Ayub Khan actively encouraged foreign investment, and touched off rapid industrialization through widespread privatization of the economy and massive infrastructure projects.

Meanwhile, India had followed a different course. Jawaharlal Nehru, a democratic socialist and close ally of Gandhi, became the country’s first prime minister. In large part due to the grassroots nature of the INC, its established dominance, and massive popularity, India remained relatively stable. Like, Pakistan, India dissolved its dominion status in favour of a semi-presidential republic, but unlike Pakistan, authority clearly remained with the prime minister. In its first general election since becoming a republic, Nehru and the INC were returned to power with a gargantuan supermajority [4]. Free to pursue his political agenda, Nehru adopted a mixed economic model, with private industry but a powerful public sector with a large amount of government oversight. Nehru moved closer to the Soviet Union than with any other of the major powers, but kept them at arm’s length, becoming a founding member of the international Non-Aligned Movement, a socialist-leaning and anti-imperialist organization, co-founded by Yugoslavia, Egypt, Indonesia, and Ghana. However, thanks to non-alignment, both the United States and Soviet Union tried to curry favour with India with foreign aid, which, along with Nehru’s policies, fostered rapid industrialization and land reform. Unlike the frequent leadership changes in Pakistan, Nehru remained prime minister for the entirety of the 1950s, being re-elected with an increased supermajority in 1957.

Throughout the 1950s, Pakistan and India remained in a stand-off over Kashmir; while India was militarily superior, it also had to worry about possible intervention from Pakistan’s ally China. The balance of power made it undesirable for either side to start a war. However, tensions increased between India and China following the Chinese annexation of Tibet, which expanded the border between the two countries. Disagreements over where the border was prompted China to launch a border war in 1962 to secure what it called the “Line of Actual Control,” resulting in a quick victory for China and an embarrassing defeat for India. Sensing weakness after the Sino-Indian War and the death of Nehru in 1964, Ayub Khan provoked a second war over Kashmir in 1965 by encouraging border skirmishes and sending infiltrators to provoke an uprising among the Muslim population. In reaction, India launched a conventional invasion of West Pakistan. Engrossed by the Vietnam War, President Lyndon Johnson put an arms embargo on both countries, and left it to the Soviet Union to arbitrate a ceasefire. With negotiations overseen by Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin, Ayub Khan and India’s second prime minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri, signed the Tashkent Agreement, restoring the status quo. Shastri died a day after signing the agreement, and he was succeeded as prime minister by Indira Gandhi, the daughter of Nehru [5].

Pakistan was the only major country in the world to be an exclave nation; the Muslim majority territories granted to Pakistan during the partition of India were not geographically connected.

By the time of the McCarthy Administration, the geopolitics of the India-Pakistan rivalry had grown even more convoluted. East Pakistan had become increasingly disgruntled with the political dominance and economic favouritism toward West Pakistan under the Ayub Khan dictatorship. Taking advantage of the unrest, the Awami League (AL) and its leader, Sheikh Muhibur Rahman (more commonly known as Mujib), rose to prominence. The AL was a Bengali nationalist party, with members ranging from liberals to democratic socialists, and based its policies around six non-negotiable demands known as the six points. They included a demand for democratic elections and an incredibly weak federal government, with West and East Pakistan each having their own currency, military, and tax agencies. Pro-AL Bengali unrest came to a head in 1968 at the same time as widespread student protests in West Pakistan, egged on by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the founder of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). A former cabinet minister for Ayub Khan from West Pakistan, Bhutto was notoriously hawkish against India, and had resigned in protest of the Tashkent Agreement. Leaving the government, Bhutto reinvented himself as a populist opponent of the presidential dictator. Both Mujib and Bhutto were arrested by Ayub Khan early into the 1968 protests, which ultimately lasted over a year. Ayub Khan’s efforts to negotiate a political compromise with all the parties but the AL and PPP fell apart, and Ayub Khan’s protégé, General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan [6], removed him in a coup. Yahya Khan enforced martial law, but also dissolved West Pakistan, reverting it to its original provinces, and declared that he would hold the first general election in Pakistan’s history in order to form a new government and draft a new constitution. Privately, Yahya Khan had less idealistic motives. He believed that permanent martial law was untenable, and wanted to introduce a mixed government following “the Turkish model,” where a civilian prime minister and legislature would govern day-to-day, but the president (in this case, Yahya Khan) and the military would reserve the right to control the political process as they saw fit. Bhutto and the PPP eventually became his chosen civilian collaborators, as the two agreed on the role of the military in government, and both opposed autonomy for East Pakistan. Running a populist campaign, Bhutto called for greater democracy, a policy of Islamic Socialism, and guaranteed “Food, Clothing, and Shelter.” He also began associating himself with Mao Zedong and the Communist Party of China (CPC), and called for an end to Pakistan’s alliance with the United States [7]. Besides the PPP, Yahya Khan also supported various smaller parties that had splintered from the old Muslim League in the hopes that no party could form a workable government, forcing another election and extending military rule. In the east, while Mujib was personally inclined toward socialism, he stuck to the social democratic party line, and capitalized on the fact that the AL was the only major party in East Pakistan advocating for the overwhelmingly popular position of provincial autonomy. To his surprise, when the election was held in December of 1970, the AL won an outright majority with one hundred and sixty seats, all of which were in East Pakistan. While Bhutto and the PPP were the clear winner in the western provinces, they still trailed far behind Mujib and the AL, at around half their level of support. The next six parties were various conservative splinters of the Muslim League.

Publicly, Yahya Khan declared that the National Assembly would convene in March of 1971 to draft the constitution, and referred to Mujib as the next prime minister. However, in private, he sabotaged the negotiations between the AL, the PPP, and the military; Yahya Khan and Bhutto refused to allow any of Mujib’s six points into the constitution, and Bhutto threatened to boycott the National Assembly if Mujib used his majority to do it without any other party. Yahya Khan also encouraged the various Muslim League parties to do the same. Using the absence of any party from the western provinces, Yahya Khan would then prolong military rule until an agreement could be reached, a process he would stretch out indefinitely. Once March arrived, Yahya Khan declared the postponement of the convening of the National Assembly due to the lack of an agreement, and used the ensuing protests in riots in East Pakistan to launch a military crackdown. He had been discretely funneling the Pakistani army to the east just for this. Titled Operation Searchlight, Yahya Khan’s simple plan was to brutalize the Bengali population until they capitulated to the political dominance of the western provinces, remarking, “Kill three million of them and the rest will eat out of our hands.” Mujib was quickly arrested and put in solitary confinement in the western provinces, and in his absence, the newly declared Provisional Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh was led by Tajuddin Ahmad, the General Secretary of the AL.

Operation Searchlight precipitated a geopolitical crisis where, ironically, every single global and regional power was equally opposed to the crackdown and Bangladeshi independence.

In India, Indira Gandhi had a won a majority government shortly before Operation Searchlight was launched. Gandhi had seen declining support in the 1967 election, facing economic difficulties and a Maoist uprising led by the Community Party of India (Marxist) known as the Naxalite insurgency. The Naxalites were mostly located in the country’s east, and were in contact with the various Maoist groups of East Pakistan. Gandhi had also caused a split in her party after she had backed a different candidate for president than the old guard of the INC, but managed to defeat them with her 1971 majority. Despite wanting to address domestic issues, Operation Searchlight caused a massive refugee crisis, as East Pakistan’s Bengali population fled into India to avoid the widespread massacres being perpetrated by the Pakistani army. Providing refugee camps for the fleeing Bengalis, the humanitarian effort quickly began to cost over a billion rupees, and destroyed the national budget. Gandhi believed that an independent Bangladesh would stake a claim on the Indian province of West Bengal, as well as that a prolonged war could potentially cause the Bengali Maoists to take over the liberation war and empower the Nexalites. Because of this, Gandhi desired a quick negotiated settlement, with Bangladesh returning to Pakistan with greater autonomy.

In the United States, Eugene McCarthy saw the crisis in terms of his moral responsibility to reign in America’s ally Pakistan, while also looking to improve relations with India. Traditionally, the Republican Party and the Defense Department supported Pakistan, while the Democratic Party and the State Department preferred India, and this rule did not find an exception under the McCarthy Administration. President McCarthy, Secretary of State J. William Fulbright, Secretary of Treasury John Kenneth Galbraith, and US Ambassador to the UN Chester Bowles (the latter two had both served as Ambassador to India) all believed they should pressure Pakistan into negotiating with the Provisional Government, but there was disagreement over if should be done by withdrawing all economic and military aid or only threatening to do so. Also complicating the matter was McCarthy’s attempts to open up relations with China, as Pakistan served as the diplomatic conduit for the secret talks. McCarthy did not clearly state a preference for total withdrawal of aid, private pressure, or a mixed approach, leaving it to the cabinet to decide. With confusion over what their policy actually was, the United States did not formulate an effective strategy until mid-May of 1971, but regardless, they desired a quick negotiated settlement, with Bangladesh returning to Pakistan with greater autonomy [8].

In the Soviet Union, there was a sense that they had a responsibility to maintain peace on the India subcontinent due to their role in the Tashkent Agreement. The General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (and the Soviet Union’s de facto leader), Leonid Brezhnev, was fairly uninvolved with events in India. The Soviet effort was mostly overseen by Premier Alexei Kosygin, with assistance from Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Gromyko, and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet Nikolai Podgorny. While typically aligned with India due to their mutual enemy, China, the Soviets had also begun selling weapons to Pakistan on the side, in order to have diplomatic clout with both countries. The Soviets feared that if Bangladesh became independent, it would be vulnerable to a Maoist takeover and would become subservient to China. They also questioned the socialist credentials of the AL, which they believed was beholden to the capitalist petit bourgeois middle class. In order to maintain the balance of power, the Soviets pressured the Communist Party of India [9] to also support their position: they desired a quick negotiated settlement, with Bangladesh returning to Pakistan with greater autonomy.

Lastly there were the Chinese. Given the impression by their ally Yahya Khan that a negotiated settlement between the AL and the PPP had been imminent in February of 1971, the Chinese were perturbed by Operation Searchlight, and Premier Zhou Enlai took over their diplomatic efforts. Zhou thought that the attack against East Pakistan was dangerously reckless, as it left the western provinces open to a military intervention by India or the Soviet Union. Facing a possible war on two fronts if the Soviets attacked with Indian support, the Chinese had decided to improve relations with India. Likewise, China was in dire straights due to the ongoing violent reforms and purges orchestrated by the Chairman of the Communist Party of China and the nation’s paramount leader, Mao Zedong. Militarily speaking, China was in no position to support Pakistan in a war with India, even if they wanted to. Zhou was also concerned that, since the Maoist parties of East Pakistan support independence, they would be annihilated by Yahya Khan in the ongoing crackdown. Ironically, the Chinese had the opposite concern of the Indians and Soviets; they knew that the Bengali Maoists were not nearly strong enough to take control of the Provisional Government from the AL, and believed that the faux-socialist Mujib would align with the Soviets in the event of independence. In order to prevent a Soviet takeover while also keeping the Bengali Maoists from getting killed while still maintain close ties with Pakistan there was only one solution: they desired a quick negotiated settlement, with Bangladesh returning to Pakistan with greater autonomy.

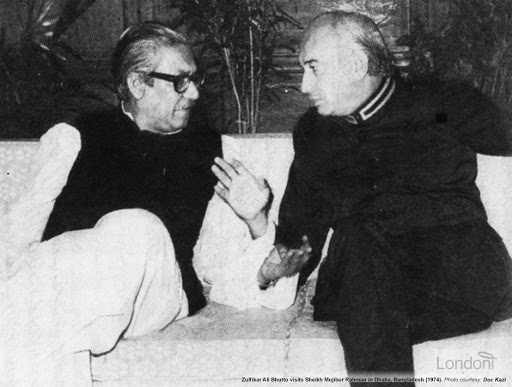

Yahya Khan (left) and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (right). Trying to prolong military rule in Pakistan, President Yahya Khan precipitated the Bangladesh Liberation War. A prominent political leader in West Pakistan, Bhutto collaborated with the military regime at first.

But even beyond Pakistan, the People’s Republic of China had its own problems.

Formally established in 1949, the People’s Republic of China was born civil war and foreign invasion. Originally, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was allied with the National Party of China, or Kuomintang (KMT), led by Sun Yat-sen. The KMT became a leading force in the aftermath of the 1911 Xinhai Revolution that toppled the Qing Empire and created the Republic of China, but the country remained fractured by warlord states and competing governments. Sun’s ideology reflected nationalist, democratic republican, and some socialist values, and besides working with the CCP, also maintained good relations with the newly formed Soviet Union. However, following Sun’s death in 1924, tensions grew between the KMT’s authoritarian anti-communist right wing faction, led by General Chiang Kai-shek, and the communist-sympathetic left wing faction, led by Wang Jingwei [10]. After defeating several northern warlord states, Chiang gained the upper hand, took control of the KMT, and purged the communist elements from the left wing in a series of massacres. Following this betrayal, the CCP broke out on its own, and launched an uprising in Nanchang in south-central China. While the CCP’s expectations of a mass peasant uprising proved overly-optimistic, pockets of revolutionary communism mushroomed across southeast China for much of the 1920s and up until the mid-1930s. In a series of encirclements, the CCP’s Red Army was forced to go on a fighting retreat from the southeast into the mountains of north-central China around the area of Shaanxi. Immortalized as the Long March, the most powerful group to survive the trek was led by the revolutionary Mao Zedong, and his lieutenant Zhou Enlai. With the past leadership discredited by the failure of the southeastern uprisings, Mao became the de facto leader of the CCP in 1935, and changed the CCP’s tactics from mass uprisings and conventional battles to one of guerilla warfare and building a base of popular support among the peasantry rather than the traditional communist base of the urban proletariat. Cautious of Japanese encroachment into China throughout the interwar period and aware it would be impossible to defeat the KMT outright, Mao and Chiang agreed to a truce shortly before the Second Sino-Japanese War. As the KMT suffered a series of conventional military defeats and were forced back further inland, Mao conserved the strength of the Red Army, despite it ballooning in size as the Japanese became a bigger threat. Following the Soviet invasion of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo in northeast China and the atomic bombing of Japan in 1945, Mao was able to position himself as a viable alternative for the leadership of China. When the Chinese Civil War resumed in 1946, Mao used evasive tactics and rapid maneuvering to eventually crush the KMT. By 1949, the communists were in effective control of the country, and Chiang and his supporters fled off the coast to the island of Taiwan, where they continued to claim to be the only legitimate government of China.

With the stunning turnaround of the CCP’s fortunes between 1935 and 1949, Mao became an irreplaceable facet of the communists’ legitimacy in the country, and he was effectively unquestioned as leader despite the theoretical power of the party over the Chairman of the Communist Party of China. Despite this, Mao faced the new problem that he had earned his legitimacy as a wartime leader, and had no experience or great knowledge in building national institutions or a fully functional peacetime economy. However, in the early stages of the economic recovery under the direct control of Mao, from 1949 to 1957, the country enjoyed a miraculous-seeming rebound. Infrastructure and institutions were rebuilt, land was redistributed to the peasants (who remained Mao’s strongest base of support), and much of the property that had been occupied by the Japanese was nationalized. In a few short years, industrial production had improved by a staggering one hundred and forty-five percent, generating tens of billions of yuan in revenue. But, the improvements were somewhat deceptive, as they were not so much caused by a socialist planned economy as they were by the fact that, for the first time in nearly half a century, there was one government with a continuous economic policy for the entire country. The economy reaching an all-time high in 1957, Mao felt justified in introducing a new program of breakneck industrialization to catch up with the rest of the developed world that he called the Great Leap Forward. Receiving absurdly optimistic reports of agricultural and mineral production, the Party Central Committee, at Mao’s direction, pushed quotas even higher, and also raised the punishments for failing to meet the quotas. As a result, nearly forty million peasant farmers were redirected to mines and backyard forges to dig up and melt down as much metal as possible with which to build a new Chinese society. These policies soon backfired; trying to reach the demand of the unrealistically high quotas, much of the metal was of subpar quality and unusable, and with a huge number of farmers no longer farming, there were not enough people to harvest the season’s crops. With the situation exacerbated by a series of droughts and floods, a devastating famine developed. Initially unwilling to admit fault in his policies, Mao removed Defense Minister Peng Dehuai and his “anti-party clique” for criticizing the Great Leap Forward at the Eighth Plenum of the Eighth Central Committee in 1959, replacing him with General Lin Biao. As the famine continued for three more years, Mao was eventually forced to concede that mistakes had been made after tens of millions had died, and at the Tenth Plenum of the Eighth Party Central Committee in 1962, he relinquished control of economic policy to the supporters of Chairman of the People’s Republic of China Liu Shaoqi [11], namely Zhou Enlai, Chen Yun, and Deng Xiaoping. While the Great Leap Forward reversed much of the earlier economic recovery, Mao still remained irreplaceable in the eyes of the senior leadership of the CCP, and he remained paramount leader, retaining policy control in all other areas.

Immediately after the Liu clique began to manage the economy Mao reached the nadir of his power, but he quickly rebounded. Announcing the Socialist Education Movement in 1963, a movement designed to raise awareness of what Mao believed to be hidden revisionist and rightist elements in the country looking to bring about a capitalist restorage by building up an anti-revolutionary “privileged class” within the party. Mao planned to expand the Socialist Education Movement to all levels of society, to encourage a state of permanent revolutionary class struggle against the forces of reaction and capital, which, besides suiting his ideological beliefs, would allow him to denounce senior members of his own government, then rehabilitate them once they had seen the error of their ways for ‘deviating’ from Mao Zedong Thought. Liu was the first to suffer this fate, and in 1965 he and his clique (with the exception of Zhou) were demoted for being “capitalist roaders.” A startling turn of events considering Liu’s unofficial status as Mao’s second-in-command, Mao reshuffled the leadership structure of the CCP to make Defense Minister Lin Biao the sole Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, declaring him his official successor and closest comrade-in-arms. Party members deemed by Mao to be mostly loyal but still mistaken in some way were forced to make self-criticisms in the form of a public address or letter, at risk of being demoted or removed like Liu if they did not comply. Soon after, Mao’s expanded movement, known as the Cultural Revolution, was declared. The Central Cultural Revolution Small Group (CCRSG) was formed to help oversee its proceedings, a group that was dominated by Mao’s politically active wife, Jiang Qing.

As the Cultural Revolution escalated, Mao encouraged students, soldiers, and workers to form paramilitary gangs known as the Red Guards, telling them that they should attempt to forcibly seize power from local CCP officials to form their own revolutionary committees. As the Red Guard were empowered, they began destroying historical landmarks around the country, and hundreds of thousands of Chinese, including senior party members, were attacked for being bourgeois reactionaries or otherwise subversive, with tens of thousands being tortured or killed. While the military leadership of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) were cautious of the Cultural Revolution and were able to maintain discipline in their ranks for the most part, they were also stopped from preventing the Red Guards from doing anything, as Mao continued to actively support them. By 1967, various Red Guard factions had developed bitter rivalries, and began engaging in shoot-outs with each other, as weapons were widely distributed from raided PLA depots. As tensions between the CCP bureaucracy and old guard, and the CCRSG and Red Guards grew worse, Mao declared that the matter should be resolved by a civil war, and told the PLA to support “the left” without specifying rather that was the CCP or CCRSG. Without any clear central authority and with local governments being taken over by the Red Guards, regular Politburo meetings were cancelled, with the CCP being factionalized between Jiang Qing’s CCRSG and Lin Biao’s Working Group of the Central Military Committee (WGCMC).

Despite having been married to Mao since 1938, Jiang Qing’s entry on to the political scene came as a surprise to many, as she had appeared politically uninvolved up until then. Rather than out of any personal disinterest, this had rather been because of an agreement made that she would prioritize her wifely duties and support Mao’s career for thirty years before entering politics herself. Once put on the CCRSG, Jiang took advantage of the position to act as the spokeswoman for Mao’s policies and the Cultural Revolution, though she often ‘interpreted’ what Mao said to support her own positions and improve her power at the expense of the established members of the CCP. This made it difficult for the party old guard to overtly criticize or weaken her, as they could never be sure when she was actually operating on Mao’s unquestionable orders, and when she was using her own interpretations to further herself. An advocate of the most extreme tendencies of the Cultural Revolution, Jiang was at odds with Lin. A leading general during the Chinese Civil War, Lin had managed to slide his way up to the position of Mao’s designated successor despite persistent poor health and a complete disinterest in politics. Having received both neurological damage and manic depression during the war, Lin had consistently tried to talk Mao out of appointing him to higher and higher positions from the 1950s onward. Mao rarely listened to Lin’s self-deprecation, however, as he considered Lin one of his most loyal supporters, and that was indeed true, or at least in public; Lin had intentionally cultivated a reputation as submissively and sycophantically pro-Mao, and helped implement his policies despite his frequent private criticisms of Mao, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution. Rather than live out his days in intentional mediocrity, Lin instead found himself as the figurehead of the CCP’s and PLA’s ‘conservatives,’ those who were anti-Jiang, and anti-Cultural Revolution. While still paying lip service to the Cultural Revolution, Lin worked behind the scenes to minimize its effects on the PLA and curtail Jiang’s influence. But, by 1971, Lin’s power had begun to decline. With the PLA being the only stable institution left in the country, Mao was paranoid that Lin would use the possibility of a war with the Soviet Union to supplant him as paramount leader or even launch a military coup. Mao also believed that Lin’s opposition to opening relations with the United States was part of scheme to maintain a war footing and empower the PLA [12]. Deciding to do away with his Vice Chairman, Mao went on a whistle-stop tour of southern China to meet with regional CCP leaders to prepare them for Lin’s demotion and removal from the party. However, this decision prompted secret plans for an actual pro-Lin military coup that the man himself did not even know was happening.

Receiving a prestigious education and quickly rising through the ranks of the PLA in large part due to nepotism, Lin Liguo, Lin Biao’s son, was the deputy director of the Office of the Air Force Command, in the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF). Having come of age after the Chinese Civil War had ended and with no great respect or admiration for Mao, Lin Liguo had a self-confidence that bordered on the egomaniacal, using the chaos of the Cultural Revolution to take control of part of the PLAAF’s bureaucracy and using its budget to go on vacation and host parties for his clique of air force officers. However, Lin Liguo also held genuine political beliefs, being a firm supporter of Marxism-Leninism, and believing that Maoism had proven itself a catastrophic deviation from a proper communist society through the disasters of the Cultural Revolution. Catching wind of Mao’s plans to remove his father, Lin Liguo made a secret plan titled Project 571 [13] to assassinate Mao and have his father take over the country. In the outline of the plan, Liguo denounced Mao as “a paranoid and sadist” whose ideology amounted to “a Trotskyite clique… [and] social fascism.” However, the outline was more of a political polemic rather than a detailed plan to seize power, with only a handful of air force squadrons and army divisions being considered loyal. While Lin Liguo prepared to assassinate Mao, Lin Biao was at the family compound at the resort town of Beidaihe. On September 8th of 1971, on the verge of Lin Biao being purged from the party, Li Liguo forged his father’s signature to present orders to try assassinate Mao. Lin Liguo and his collaborators began to prepare various possible methods to kill Mao, including attacking his train with flamethrowers and bazookas, a napalm attack, walking up to Mao and shooting him, blowing up fuel tanks attached to the train, or dropping a bomb on the train, among other proposals. However, the matter was complicated by the fact that few in the group were totally committed to assassinating Mao, and one conspirator, a pilot, rubbed salt and chemicals into his eyes so that he would not have to fly the plane if they decided to drop a bomb on the train. Without any serious consideration for a plan, on September 11th of 1971, Lin Liguo and his collaborators eventually settled on the idea of attaching time bombs to the undercarriage fuel tanks of Mao’s train while it was in Shanghai, after realizing that they would not be able to get any heavy armaments into position. A plan to launch a simultaneous attack against Jiang’s Beijing villa was abandoned for similar reasons, and also because they could not find anyone willing to do it.

Able to access the security perimeter due to their high military rank, Lin Liguo left his air force officers to plant the bombs, while he left for Beidaihe, contacting Lin Biao’s closest generals (namely Wu Faxian, Li Zuopeng, Huang Yongsheng, and Qiu Huizuo) to meet them there. In an atmosphere of general confusion and with Premier Zhou Enlai investigating the strange happenings around Lin Biao, reports began to trickle in that Mao’s train had derailed. Without a clear idea of what was happening, Lin Liguo took his father and his mother, Ye Qun, along with the generals, on board Lin Biao’s private jetliner to the south in Guangzhou. During the flight, Lin Liguo tried to convince the generals to declare a rival government in Guangzhou, but they were uniformly horrified that Lin Liguo had actually attempted to assassinate Mao. Made complicit in the attempt by simply being on the plane, Lin Biao and the generals decided that the best course of action was to re-route to Hong Kong. Although the Lin clique did not yet know it, by the time they touched down in Hong Kong in the early morning of September 12th, Mao Zedong’s death had been confirmed to senior members of the government [14].

Despite having no actual role in it, Lin Biao found himself the mastermind of an attempt to take over the country [15].

The paramount leader of China, Mao Zedong (left), with his designated successor, Lin Biao (right). With Mao threatening to remove Lin from office, an amateurish conspiracy of air force officers developed around Lin that ultimately succeeded in assassinating Mao, but failed to take power due to a total lack of popular support, including a lack of support from Lin himself.

Overnight, China became enveloped in chaos. Its paramount leader was dead under mysterious circumstances, and his only legal successor was missing, having left the country for reasons unknown. In the immediate aftermath, Zhou Enlai became the de facto leader of China, using his immense legitimacy within the CCP and his de jure title as head of government to assert some semblance of authority, while Jiang Qing gathered together her own supporters from the CCRSG and the Red Guards. But, with China rudderless, it presented the perfect opportunity for India to resolve the crisis in East Pakistan.

Throughout the summer of 1971, the armed forces of the Bangladeshi Provisional Government, the Mukti Bahini, had changed gears from conventional battles with the invading Pakistan Armed Forces to guerilla warfare after early defeats and with the encouragement of the Indians. Despite Yahya Khan’s faith in the expediency of mass slaughter, stiff resistance continued, and by September, his position had become completely untenable. As millions of refugees continued to pour in to India, Indira Gandhi and her administration began giving more and more obvious military assistance to the Provisional Government; her economists had concluded that a war to clear the Pakistanis out of Bangladesh and then sending all the refuges back would be cheaper than putting up with a long crisis, and they were looking to provoke Pakistan into attacking India. India was also bolstered by the Indo-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, which was signed in August. With intentionally very vague wording, the Indians could still claim to be part of the Non-Aligned Movement, while the Soviets made it clear that they would become involved if either the Americans or the Chinese did. However, in international forums, the Soviets made it clear that their priority was a peaceful resolution and the continuation of a united Pakistan, supporting various motions put forward by the Arab states in support of the Pakistani position. Mao’s assassination on September 11th effectively knocked the Chinese out of contention, guaranteeing the Indians that the Chinese would not militarily interfere. But, the final nail in the coffin for Pakistan was the withdrawal of all American military and economic aid at the end of September. An early and forceful push from McCarthy to end all aid in May may have forced Yahya Khan to concede to the AL’s six points and keep Pakistan unified. Instead, the fumbled response stretched out American bureaucratic infighting and attempts to broker a peace deal for months, by which point neither side was willing to negotiate. With American withdrawal, economic obliteration for Pakistan was guaranteed by 1972, by which point they would have to pay off all its foreign aid debt to the United States to the tune of several hundred million dollars, or default on its loans to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Either way, it would drive the nation to bankruptcy.

With nothing left to lose, and already effectively in a state of undeclared war in the east, Yahya Khan made one last gambit to decisively win by launching a pre-emptive strike against India in October. Betting that the international community would not allow a war to go on for long, Yahya Khan planned to take as much Indian territory in the northwest as possible, and exchanging it for Bangladesh. Emulating the Israeli attack on Egyptian airfields prior to the Six-Day War but with much less success, the Pakistani air force bombed Indian airbases near the border. Making paltry initial gains in the west, the Pakistanis were completely overwhelmed in the east. As Yahya Khan had predicted, it was a short war due to international pressure, but one the Indians decisively won, and a ceasefire was declared soon after the Pakistani military presence in the east surrendered [16].

Although none of Asia’s crises would be fully resolved by the end of 1971, the Sihanouk purge, Bangladesh Liberation War, and Lin Biao conspiracy redefined the balance of power in Asia, and not necessarily in America’s favour. Leaving a neutralist regime in power in Cambodia and cutting ties with Pakistan left the United States with exactly two allies on mainland east Asia: Thailand, and South Korea. And, with China embroiled in a power struggle, a potential rapprochement was delayed indefinitely.

If nothing else, the Vietnam War provided a clarity of who was America’s allies and who were their enemies – at least at first – but with the war over and Asia still embroiled in conflict, people wondered if that had ever been true to begin with.

[1] IOTL, the local CIA mission gave approval for the coup, in an attempt to limit North Vietnamese military access to South Vietnam. After being pressured by Sirik Matak, Lon Nol abolished the monarchy, and ruled as military dictator before a coalition between Sihanouk and the communists under Saloth Sâr (later and more commonly known as Pol Pot) toppled him, and Sâr's Khmer Rouge regime came to power. It is unclear if the Nixon Administration gave approval or were even aware of the planning stages of the coup. However, ITTL, with the American presence withdrawing and operational control being centralized under McCarthy's appointees, the information made its way up the chain of command. Ironically, In Tam, who Sihanouk is now reliant on to govern, supported the coup after it happened IOTL.

[2] The North Vietnamese actually did try to assassinate Saloth Sâr in November of 1970 in this way. However, due to Lon Nol’s successful coup IOTL, the communists groups and Sihanouk’s Sangkum worked together to depose the new regime, and so the split was not quite as drastic as ITTL.

[3] The Muslim tribal militia attack against Jammu and Kashmir remains highly controversial, as India believed that the tribals were encouraged and equipped by the Pakistani government, while Pakistan insisted it was a show of spontaneous patriotism, and that the modern military hardware they had must have been gotten from sympathetic members of the military not acting on the government’s orders.

[4] To put the sheer size of the INC’s victory into perspective, it won three hundred and sixty-four seats and forty-four percent of the vote. The runner-up, the Communist Party of India, won sixteen seats and three percent of the vote.

[5] The Nehru-Gandhi political dynasty was not biologically related to Mohandas Gandhi.

[6] There was also no biological relation between Ayub Khan and Yahya Khan.

[7] Contrary to his far left campaign rhetoric, Bhutto was a centre-left social democrat with authoritarian tendencies, and he privately assured the Americans that he would continue to work with them and the military junta.

[8] IOTL, President Nixon and his National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, quickly decided in April of 1971 that they would publicly support Pakistan, while privately pressuring them into a negotiated settlement. They believed a quick negotiation would stabilize Pakistan as much as possible under the circumstances, and would prevent India from gaining too much power, which Nixon and Kissinger believed was effectively a Soviet puppet state. Their decision was based off of their race to normalize relations with China before the next presidential election, Nixon’s favourability toward Pakistan as an American ally, Nixon’s personal dislike of Indira Gandhi and racism against Indians (which, bizarrely, did not seem to extend to Pakistanis), and a prioritization of policy goals over humanitarian concerns.

[9] The pro-Soviet Communist Party of India (CPI) was distinct from the Communist Party of India (Marxist), or CPI (M), which was supporting the Nexalite Maoist revolutionaries in eastern India. India’s far left had a tendency to use very similar names. Besides the Communist Party of India and the Communist Party of India (Marxist), there would also eventually be the Communist Party of India (Maoist), the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) Liberation, and the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) New Democracy, among others.

[10] Wang would strangely become the leader of those Chinese who collaborated with the Japanese during the Second Sino-Japanese War. He was very pessimistic about China’s chances of winning against Japan, and claimed that western imperialism was a greater threat to China than Japanese aggression while in the midst of a war with Japan. There was almost certainly a self-serving element to Wang’s defection as well, so that he could finally be in power instead of his old rival Chiang.

[11] Liu’s title of Chairman of the People’s Republic of China was distinct and lesser to Mao’s title of Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party.

[12] Ironically, according to Lin’s private staff, he actually supported working more closely with the United States, but publicly condemned the idea, as he thought that was what Mao wanted.

[13] Project 571 was chosen as the name as, in Chinese, ‘571’ is a homophone of ‘armed uprising.’

[14] IOTL, Mao rescheduled his route and left a day early, before the Project 571 conspirators had actually decided what they were going to do. Official Chinese government sources claim that after Mao’s train left early the conspirators attempted to attack Mao’s train further down the track, while most third party sources believe that the attempt on Mao’s life never left the planning stage, although further last-ditch plans were drawn up once Mao arrived in Beijing after leaving from Shanghai early.

[15] The historiography of the Lin Biao incident is highly controversial. According to official Chinese government sources, Lin Biao himself was a power-hungry militarist who was deeply involved in the conspiracy from the start. Other sources (usually from Western, anti-communist leaning circles) claim that Lin Biao was marginally involved but that most of the planning was done by Lin Liguo. I have followed a more recent historiographical trend of the Lin Biao incident that began in the mid-1990s that was corroborated by several historians and researchers that indicate that Lin Biao himself had no actual knowledge of the attempt, and that the whole thing was an incredibly amateurish attempt by Lin Liguo and his clique of air force officers to prevent his father from being removed from power. This viewpoint was primarily laid out in The Culture of Power by Jin Qiu, Bringing the Inside Out by Adrian Luna, and The Tragedy of Lin Biao by Frederick C. Teiwes and Warren Sun.

[16] This is very similar to what happened IOTL, but with China indisposed, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 took place two months earlier.

A semblance of peace had finally come to Vietnam with the election of the communist fellow traveller Trần Văn Hữu as President of South Vietnam and the deposition of Lê Duẩn by Trường Chinh for the title of General Secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam. Likewise, peace had come to Laos after royalist forces were compelled into forming a coalition government with the communist Panthet Lao and their leader, Prince Souphanouvong, in the midst of American military withdrawal. However, the events of the early 1970s proved that Asia would remain wracked by conflict even without American help.

Like South Vietnam and Laos, the neutralist regime of Chief of State (and former King) Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia had entered into a coalition with communists. However, unlike the former two, Sihanouk had done so years earlier, and had them purged from the government completely in 1968. Since then, Sihanouk's political organization Sangkum had been dominated by right wing elements, led by Prime Minister Lon Nol. However, for his tolerance of North Vietnamese troops crossing his territory, Sihanouk was still considered an ally of communism by the international socialist fraternity. Because of this, Cambodia's communists either fled to North Vietnam, or aligned with the rural guerillas of Saloth Sâr, one of the country's most radical communists who had refused to work with Sihanouk from the start.

After years of supporting the rightist elements within Sihanouk's regime, the United States' last act before withdrawing completely from his country was to warn him of a coup by those very same rightist elements. Besides being prime minister, Lon Nol was also the leader of the armed forces. Frustrated with Sihanouk's tolerance of the Vietnamese communists, Lon Nol intended to use anti-Vietnamese sentiments to whip up a riot, then launch a soft coup to compel Sihanouk to cut all ties with North Vietnam. However, Lon Nol's co-conspirator, Deputy Prime Minister Sisowath Sirik Matak, wanted to remove Sihanouk completely, abolish the monarchy, and install a republican military dictatorship. Needing the tacit approval of the CIA mission in the country either way, the plotters informed them of the plan. But, rather than supporting the coup, the CIA informed Sihanouk of the plan, on the orders of President McCarthy and Director of the CIA Thomas McCoy. Using loyalists in the police under the control of his brother-in-law, Secretary of State for Defence Oum Mannorine, Sihanouk had the plotters arrested in early 1970. In the ensuing purge, Sihanouk put much of the military's duties in the hands of the police. Both military loyalists to Lon Nol and Sirik Matak's clique in the National Assembly were rounded up and put under arrest. With the military leadership and Sirik Matak clique removed from office and the leftists having been exiled years ago, Sihanouk's government became entirely reliant on the liberal democratic centre led by the parliamentarian In Tam [1].

The aftermath of the failed coup left Cambodia divided between two powers that were both divided amongst themselves. The Sangkum government was split between Sihanouk's autocratic loyalists and In Tam's parliamentary liberals in an incredibly fragile government but one with no real opposition. The communists were split between Saloth Sâr's Communist Party of Kampuchea (Nationalist), which refused to cooperate with any other group and continued guerrilla action against Sihanouk, and Son Ngoc Minh's Communist Party of Kampuchea (Internationalist). A longtime ally of the Vietnamese communist movement, the elderly Son Ngoc Minh was selected by the North Vietnamese as a cooperative, relatively moderate alternative compared to Saloth Sâr. Rather than direct confrontation, the Internationalists instead followed Trường Chinh's policy of building grassroots support and taking power through political means, or at least until a united Vietnam could install them into power. Tensions would become so fierce between the two communist camps that the North Vietnamese attempted to assassinate Saloth Sâr at what was supposed to be a joint operational security negotiation, permanently dividing the two communist factions [2].

Cambodia's prime minister and leading general, Lon Nol (centre), was arrested and later executed after he was uncovered plotting a right wing coup against Chief of State Norodom Sihanouk. The subsequent purge of conservative elements in the Cambodian government left Sihanouk entirely reliant on the liberal democratic centrists in the National Assembly.

While conflict was winding down to the east, the next great crisis in Asia would emerge in Pakistan, where election interference and ethnic conflict threatened to rip the country in half.

Pakistan, as a nation, had its roots in Muslim intellectual circles of the late 19th Century and early-to-mid 20th Century. Living under the rule of the British Raj, members of the Muslim upper middle class believed that Westernization through accepting British-style education and bureaucratic methods would be the only way to stay politically relevant. To that end, they formed the All-India Muslim League (AIML) in 1906, in part as a counter to the older and larger Indian National Congress (INC). The AIML’s long-time leader, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, believed that the INC was dominated by Hindus, and that if India were to become one country a Hindu governing elite would marginalize the Muslim population. As a solution, Jinnah became a leading advocate of two-nations theory: the idea that Hindus and Muslims were too culturally different to ever peacefully coexist, and that the best solution would be a partition into two nations, one Muslim, and one Hindu. The AIML also advocated for cooperation with British colonial authorities and ‘working inside the system’ to meet their goals. This was all in contrast to the INC. Advocating an inclusive nationalism of all Indian ethnicities and creeds, the INC believed in a single indivisible Indian nation, and followed a line of civil unrest, peaceful protests, and non-co-operation made famous by Mohandas Gandhi, who, while only formally serving a short term as the INC’s president, was acknowledged as the organization’s premier leader for decades. Following highly divided election results in 1945 and 1946 (with the AIML winning overwhelmingly in Muslim areas and the INC winning overwhelmingly everywhere else), the British agreed to arbitrate a partition along the lines of two-nations theory, overseen by the last Viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten. In most cases, provinces with a clear majority were awarded to either India or Pakistan, but in two cases, provinces with a sizeable Muslim minority were also partitioned, with the Muslim portions being allocated to Pakistan. Such was the case in West Punjab and East Bengal. The princely states – parts of the British Raj ruled by various kings which had been technically independent under colonial rule – were also pressured into joining either India or Pakistan. However, problems emerged in princely states who had a ruler of one religion but a majority population of the other. This issue was most pronounced in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, to the far north of the former colony, and on the border between India and Pakistan. Although it had a Muslim majority, Jammu and Kashmir’s ruler, the Maharajah Hari Singh, was Hindu. Initially attempting to maintain his independence, Singh eventually agreed to join his state to India, after his army was defeated by Muslim tribal militias from Pakistan looking to forcibly annex his realm [3]. This triggered an inconclusive war between the two newly independent countries in 1947, which left Jammu and Kashmir divided between the two of them, and with the battle line acting as the de facto border. While the centre of conflict, the partition of India also led to widespread sectarian violence, massive riots, paramilitary skirmishes, and the largest mass migration in human history. Both Gandhi and Jinnah would die before the war’s end in 1949. The former was killed by a Hindu supremacist who believed he was coddling the religious minorities (especially the Muslims), while the latter died of tuberculosis after becoming the first Governor General of Pakistan.

Once it achieved its independence, Pakistan was notably the world’s only exclave country, meaning its territory did not geographically connect. While ‘mainland’ Pakistan was on the northwestern border of India, East Bengal, which contained most of Pakistan’s population, was far to the east, on the other side of the subcontinent. West Pakistan’s political dominance would remain a sticking point in the country that would eventually lead to war in 1971.

Following the First Indo-Pakistani War and an attempted coup by communists in the military, Pakistan’s first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, was assassinated, and Jinnah’s successor as governor general, Khawaja Nazimuddin, took his place. Despite being Bengali himself, Nazimuddin was unable to cope with widespread protests in East Bengal that demanded that the Bengali language be recognized as an official language of Pakistan along with Urdu, the most common language of the western provinces. On top of that, riots in the freshly partitioned province of Punjab continued despite Nazimuddin invoking martial law, and he was dismissed by the governor general for failing to restore order. Next was Mohammad Ali Bogra. Bogra looked to stabilize the relationship with East Bengal by reforming Pakistan’s provincial borders. East Bengal was renamed East Pakistan, while the four western provinces – Khyber Pakhtunkwah, Punjab, Balochistan, and Sindh – were merged into one province called West Pakistan. Bogra also made preparations to change Pakistan’s constitution from a British dominion to a fully independence republic that enshrined Islam into the legal system, and pursued closer relations with the United States and the People’s Republic of China. However, Bogra was dismissed by Governor General Iskander Ali Mizra after his party, the Muslim League (the official successor to the AIML), placed fourth in the 1954 East Bengal legislative election. After the passage of the new constitution, the country officially became the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, a semi-presidential parliamentary democracy, with Mizra appointed its first president by an electoral college. With no prime minister able to hold together a workable governing coalition and with a nationwide election yet to be held, Mizra continuously sacked his own heads of government. With it looking unlikely that he would win re-election, Mizra declared martial law, and dissolved his own party’s government, resulting in General Muhammad Ayun Khan launching a coup, appointing himself president and military dictator, and leaving the office of prime minister intentionally vacant. Under his rule, Ayub Khan actively encouraged foreign investment, and touched off rapid industrialization through widespread privatization of the economy and massive infrastructure projects.

Meanwhile, India had followed a different course. Jawaharlal Nehru, a democratic socialist and close ally of Gandhi, became the country’s first prime minister. In large part due to the grassroots nature of the INC, its established dominance, and massive popularity, India remained relatively stable. Like, Pakistan, India dissolved its dominion status in favour of a semi-presidential republic, but unlike Pakistan, authority clearly remained with the prime minister. In its first general election since becoming a republic, Nehru and the INC were returned to power with a gargantuan supermajority [4]. Free to pursue his political agenda, Nehru adopted a mixed economic model, with private industry but a powerful public sector with a large amount of government oversight. Nehru moved closer to the Soviet Union than with any other of the major powers, but kept them at arm’s length, becoming a founding member of the international Non-Aligned Movement, a socialist-leaning and anti-imperialist organization, co-founded by Yugoslavia, Egypt, Indonesia, and Ghana. However, thanks to non-alignment, both the United States and Soviet Union tried to curry favour with India with foreign aid, which, along with Nehru’s policies, fostered rapid industrialization and land reform. Unlike the frequent leadership changes in Pakistan, Nehru remained prime minister for the entirety of the 1950s, being re-elected with an increased supermajority in 1957.

Throughout the 1950s, Pakistan and India remained in a stand-off over Kashmir; while India was militarily superior, it also had to worry about possible intervention from Pakistan’s ally China. The balance of power made it undesirable for either side to start a war. However, tensions increased between India and China following the Chinese annexation of Tibet, which expanded the border between the two countries. Disagreements over where the border was prompted China to launch a border war in 1962 to secure what it called the “Line of Actual Control,” resulting in a quick victory for China and an embarrassing defeat for India. Sensing weakness after the Sino-Indian War and the death of Nehru in 1964, Ayub Khan provoked a second war over Kashmir in 1965 by encouraging border skirmishes and sending infiltrators to provoke an uprising among the Muslim population. In reaction, India launched a conventional invasion of West Pakistan. Engrossed by the Vietnam War, President Lyndon Johnson put an arms embargo on both countries, and left it to the Soviet Union to arbitrate a ceasefire. With negotiations overseen by Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin, Ayub Khan and India’s second prime minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri, signed the Tashkent Agreement, restoring the status quo. Shastri died a day after signing the agreement, and he was succeeded as prime minister by Indira Gandhi, the daughter of Nehru [5].

Pakistan was the only major country in the world to be an exclave nation; the Muslim majority territories granted to Pakistan during the partition of India were not geographically connected.

By the time of the McCarthy Administration, the geopolitics of the India-Pakistan rivalry had grown even more convoluted. East Pakistan had become increasingly disgruntled with the political dominance and economic favouritism toward West Pakistan under the Ayub Khan dictatorship. Taking advantage of the unrest, the Awami League (AL) and its leader, Sheikh Muhibur Rahman (more commonly known as Mujib), rose to prominence. The AL was a Bengali nationalist party, with members ranging from liberals to democratic socialists, and based its policies around six non-negotiable demands known as the six points. They included a demand for democratic elections and an incredibly weak federal government, with West and East Pakistan each having their own currency, military, and tax agencies. Pro-AL Bengali unrest came to a head in 1968 at the same time as widespread student protests in West Pakistan, egged on by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the founder of the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). A former cabinet minister for Ayub Khan from West Pakistan, Bhutto was notoriously hawkish against India, and had resigned in protest of the Tashkent Agreement. Leaving the government, Bhutto reinvented himself as a populist opponent of the presidential dictator. Both Mujib and Bhutto were arrested by Ayub Khan early into the 1968 protests, which ultimately lasted over a year. Ayub Khan’s efforts to negotiate a political compromise with all the parties but the AL and PPP fell apart, and Ayub Khan’s protégé, General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan [6], removed him in a coup. Yahya Khan enforced martial law, but also dissolved West Pakistan, reverting it to its original provinces, and declared that he would hold the first general election in Pakistan’s history in order to form a new government and draft a new constitution. Privately, Yahya Khan had less idealistic motives. He believed that permanent martial law was untenable, and wanted to introduce a mixed government following “the Turkish model,” where a civilian prime minister and legislature would govern day-to-day, but the president (in this case, Yahya Khan) and the military would reserve the right to control the political process as they saw fit. Bhutto and the PPP eventually became his chosen civilian collaborators, as the two agreed on the role of the military in government, and both opposed autonomy for East Pakistan. Running a populist campaign, Bhutto called for greater democracy, a policy of Islamic Socialism, and guaranteed “Food, Clothing, and Shelter.” He also began associating himself with Mao Zedong and the Communist Party of China (CPC), and called for an end to Pakistan’s alliance with the United States [7]. Besides the PPP, Yahya Khan also supported various smaller parties that had splintered from the old Muslim League in the hopes that no party could form a workable government, forcing another election and extending military rule. In the east, while Mujib was personally inclined toward socialism, he stuck to the social democratic party line, and capitalized on the fact that the AL was the only major party in East Pakistan advocating for the overwhelmingly popular position of provincial autonomy. To his surprise, when the election was held in December of 1970, the AL won an outright majority with one hundred and sixty seats, all of which were in East Pakistan. While Bhutto and the PPP were the clear winner in the western provinces, they still trailed far behind Mujib and the AL, at around half their level of support. The next six parties were various conservative splinters of the Muslim League.

Publicly, Yahya Khan declared that the National Assembly would convene in March of 1971 to draft the constitution, and referred to Mujib as the next prime minister. However, in private, he sabotaged the negotiations between the AL, the PPP, and the military; Yahya Khan and Bhutto refused to allow any of Mujib’s six points into the constitution, and Bhutto threatened to boycott the National Assembly if Mujib used his majority to do it without any other party. Yahya Khan also encouraged the various Muslim League parties to do the same. Using the absence of any party from the western provinces, Yahya Khan would then prolong military rule until an agreement could be reached, a process he would stretch out indefinitely. Once March arrived, Yahya Khan declared the postponement of the convening of the National Assembly due to the lack of an agreement, and used the ensuing protests in riots in East Pakistan to launch a military crackdown. He had been discretely funneling the Pakistani army to the east just for this. Titled Operation Searchlight, Yahya Khan’s simple plan was to brutalize the Bengali population until they capitulated to the political dominance of the western provinces, remarking, “Kill three million of them and the rest will eat out of our hands.” Mujib was quickly arrested and put in solitary confinement in the western provinces, and in his absence, the newly declared Provisional Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh was led by Tajuddin Ahmad, the General Secretary of the AL.

Operation Searchlight precipitated a geopolitical crisis where, ironically, every single global and regional power was equally opposed to the crackdown and Bangladeshi independence.

In India, Indira Gandhi had a won a majority government shortly before Operation Searchlight was launched. Gandhi had seen declining support in the 1967 election, facing economic difficulties and a Maoist uprising led by the Community Party of India (Marxist) known as the Naxalite insurgency. The Naxalites were mostly located in the country’s east, and were in contact with the various Maoist groups of East Pakistan. Gandhi had also caused a split in her party after she had backed a different candidate for president than the old guard of the INC, but managed to defeat them with her 1971 majority. Despite wanting to address domestic issues, Operation Searchlight caused a massive refugee crisis, as East Pakistan’s Bengali population fled into India to avoid the widespread massacres being perpetrated by the Pakistani army. Providing refugee camps for the fleeing Bengalis, the humanitarian effort quickly began to cost over a billion rupees, and destroyed the national budget. Gandhi believed that an independent Bangladesh would stake a claim on the Indian province of West Bengal, as well as that a prolonged war could potentially cause the Bengali Maoists to take over the liberation war and empower the Nexalites. Because of this, Gandhi desired a quick negotiated settlement, with Bangladesh returning to Pakistan with greater autonomy.

In the United States, Eugene McCarthy saw the crisis in terms of his moral responsibility to reign in America’s ally Pakistan, while also looking to improve relations with India. Traditionally, the Republican Party and the Defense Department supported Pakistan, while the Democratic Party and the State Department preferred India, and this rule did not find an exception under the McCarthy Administration. President McCarthy, Secretary of State J. William Fulbright, Secretary of Treasury John Kenneth Galbraith, and US Ambassador to the UN Chester Bowles (the latter two had both served as Ambassador to India) all believed they should pressure Pakistan into negotiating with the Provisional Government, but there was disagreement over if should be done by withdrawing all economic and military aid or only threatening to do so. Also complicating the matter was McCarthy’s attempts to open up relations with China, as Pakistan served as the diplomatic conduit for the secret talks. McCarthy did not clearly state a preference for total withdrawal of aid, private pressure, or a mixed approach, leaving it to the cabinet to decide. With confusion over what their policy actually was, the United States did not formulate an effective strategy until mid-May of 1971, but regardless, they desired a quick negotiated settlement, with Bangladesh returning to Pakistan with greater autonomy [8].

In the Soviet Union, there was a sense that they had a responsibility to maintain peace on the India subcontinent due to their role in the Tashkent Agreement. The General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (and the Soviet Union’s de facto leader), Leonid Brezhnev, was fairly uninvolved with events in India. The Soviet effort was mostly overseen by Premier Alexei Kosygin, with assistance from Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Gromyko, and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet Nikolai Podgorny. While typically aligned with India due to their mutual enemy, China, the Soviets had also begun selling weapons to Pakistan on the side, in order to have diplomatic clout with both countries. The Soviets feared that if Bangladesh became independent, it would be vulnerable to a Maoist takeover and would become subservient to China. They also questioned the socialist credentials of the AL, which they believed was beholden to the capitalist petit bourgeois middle class. In order to maintain the balance of power, the Soviets pressured the Communist Party of India [9] to also support their position: they desired a quick negotiated settlement, with Bangladesh returning to Pakistan with greater autonomy.

Lastly there were the Chinese. Given the impression by their ally Yahya Khan that a negotiated settlement between the AL and the PPP had been imminent in February of 1971, the Chinese were perturbed by Operation Searchlight, and Premier Zhou Enlai took over their diplomatic efforts. Zhou thought that the attack against East Pakistan was dangerously reckless, as it left the western provinces open to a military intervention by India or the Soviet Union. Facing a possible war on two fronts if the Soviets attacked with Indian support, the Chinese had decided to improve relations with India. Likewise, China was in dire straights due to the ongoing violent reforms and purges orchestrated by the Chairman of the Communist Party of China and the nation’s paramount leader, Mao Zedong. Militarily speaking, China was in no position to support Pakistan in a war with India, even if they wanted to. Zhou was also concerned that, since the Maoist parties of East Pakistan support independence, they would be annihilated by Yahya Khan in the ongoing crackdown. Ironically, the Chinese had the opposite concern of the Indians and Soviets; they knew that the Bengali Maoists were not nearly strong enough to take control of the Provisional Government from the AL, and believed that the faux-socialist Mujib would align with the Soviets in the event of independence. In order to prevent a Soviet takeover while also keeping the Bengali Maoists from getting killed while still maintain close ties with Pakistan there was only one solution: they desired a quick negotiated settlement, with Bangladesh returning to Pakistan with greater autonomy.

Yahya Khan (left) and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (right). Trying to prolong military rule in Pakistan, President Yahya Khan precipitated the Bangladesh Liberation War. A prominent political leader in West Pakistan, Bhutto collaborated with the military regime at first.