Hello, this is my second attempt at a timeline with a point of divergence pre-1800. My first attempt was merely the development of a proto-CSA over 70 years earlier and while I was initially enthused with the idea, it got stale and instead rebooted my first timeline on here which was a CSA victory in the Civil War. However, I promise this will be much more unique and a relatively-less used POD. So here it goes. The first section will not be the point of divergence itself but rather a recap of the major events heading into the point of divergence which itself will be in an update or two. In other words, it's essentially our timeline until 1774 (where the POD) is and how it is going to shape the point of divergence.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

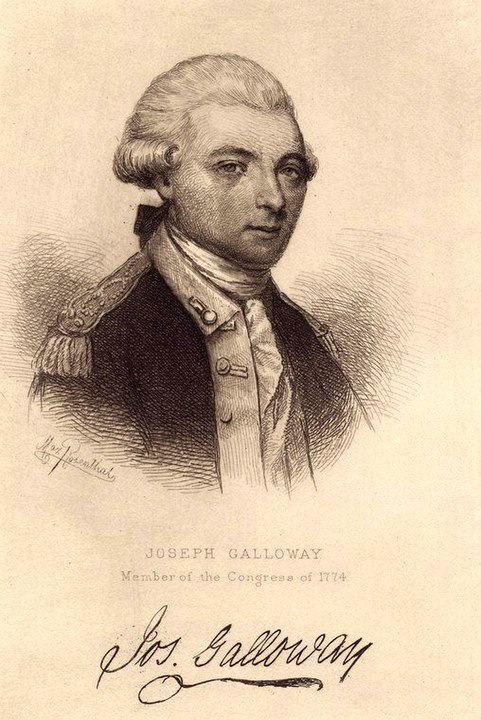

Galloway and the Plan of Union: A Saga of a British America

- Thread starter PGSBHurricane

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 36 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Twenty-Three: The UAC Parliamentary Elections of 1819 Chapter Twenty-Four: New World Problems, Old World Solutions Chapter Twenty-Five: A “Central” Continent Chapter Twenty-Six: An Independence Movement? Chapter Twenty-Seven: UAC Politics of the 1820s Chapter Twenty-Eight: An Early Period of Reform UAC Map Circa 1828 Chapter Twenty-Nine: More Reforms Across Europe

Prologue: British North America Through 1774

Prologue: British North America Through 1774

The start of the British colonization in North America began in 1607 with the settlement of Virginia (at Jamestown). In the 17th and 18th centuries, large flows of settlers immigrated to the Thirteen colonies along the Atlantic Coast from Massachusetts and New Hampshire down to Georgia and the Carolinas. By 1754, there were 1.5 million people living in mainland British North America, representing 80% of all the overall population in British North America. This dwarfed the 70,000 colonists in French North America. After the French built Fort Duquesne at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers in 1754, the British and French began the French and Indian War. The French achieved a sizable number of victories over the next two years against the British, including the defeat of a young George Washington. The British did not formally declare war on France until 1756, sparking the Seven Years War and seeing warfare across much of the world. The War ended with the Treaty of Paris in February 1763. The British received Canada and the Mississippi River Valley east of the river from France, thus removing its biggest rival from the continent.

At first, things seemed hunky dory for the Anglo-Americans. The Proclomation Act, passed by Parliament in October 1763, changed all that, as the British forbade settlement west of the Appalachian Moutains, reserving it for the Native Americans, angering many potential frontier settlers. Meanwhile, the British national debt doubled as a result of the French and Indian War. King George III decided that since the French and Indian War benefited the colonists, they should pay their fair share of the debt as subjects of the British Empire. From the perspective of the colonists, things when from bad to worse as King George III decided to install permanent British army units in the Americas, alongside various acts intended to raise revenue, including the Sugar Act, Stamp Act, and Townshend Acts, which taxed everything from glass to paint to paper. Resentment boiled over in 1770 with the Boston Massacre, where British soldiers killed five colonists. As a result, the tax on the majority of British-imported goods were revered, except for the duty on tea.

For a while, there was no major fuss in America, since the majority of the Anglo-American population smuggled in Dutch tea. Things went back up in flames in 1773 with the passage of the Tea Act. The Tea Act granted the British East India Company license to export their tea to the American colonies, opening up the American market, and the duties charge would be refunded on sale. This was not intended to anger the Americans but rather reduce the debt of the British East India Company. Nevertheless, the colonies were angry and manifested their rage in December 1773 in Boston, Massachusetts as the Sons of Liberty 340 chests of British East India Company Tea were dumped into Boston Harbor. As one would expect, this was not taken well across the pond. Determined to reassert its authority over its colonies, especially Massachuetts, Parliament passed a series of four acts known as the Coervice Acts (or Intolerable Acts in North America): the Boston Port Bill, the Massachusetts Government Act, the Administration of Justice Act, and the Quartering Act.

By then, most of the colonies, particularly Massachusetts, were at their limit for how much perceived abuse they received from their mother country. For the most part, it was enough taxation without representation in Parliament. Until 1774, most resistance to the imperial measures took place primarily through committees of correspondence rather than as a united political body. The First Continental Congress convened in September 1774 at Capenter’s Hall in Phyaldlephia, Pennsylvania to formally organize their resistance. Delegates from all Thirteen colonies, except Loyalist-leaning Georgia, were present. Some delegates like John and Samuel Adams, Patrick Henry, and Roger Sherman, believed that their goal should be to end the abuses from parliament and retain their rights under their Colonial charters and English law. Others like John Dickinson, John Jay, and Edward Rutledge thought the goal should be to develop a reasonable solution to the dilemma and reconcile the Colonies with Great Britain. One person took that a step further and proposed a Union between the Thirteen Colonies and Britaiin. That person was none other than Joseph Galloway.

Last edited:

Looking forward to your new TL! I haven’t seen one about the Galloway Plan before, so I’m excited to see where it goes (American Prime Minister Galloway?)

President-General Galloway, you mean? If I read about the plan correctly, it wouldn't work exactly like the British Parliament since the leader would be appointed by the King. And there's still one major obstacle in the way: Massachusetts. We'll see how that's dealt with.Looking forward to your new TL! I haven’t seen one about the Galloway Plan before, so I’m excited to see where it goes (American Prime Minister Galloway?)

I forgot one more obstacle: King George III himself. But he will be addressed when the time comes.

Alright, now here is the first section proper of the timeline and the point of divergence itself.

Chapter One: The Man With a Plan

Chapter One: The Man With a Plan

Joseph Galloway was born in December 1730 in West River, Maryland (part of Anne Arundel County), approximately 30 miles south of Baltimore. His participation in politics dated back to the 1740s when apprenticed with and Pennsylvania Colonial Assembly Speaker John Kinsey. By 1749, he was actively practicing law on his own in Philadlephia. At only 25 years of age, Galloway was elected to the Colonial Assembly in 1756. Upon his election, he was an active member of the Assembly, drafting 46 laws, including a number of defensive measures, before being elected speaker in 1766. He remained speaker until 1774. That’s not to say everything was all smooth sailing for Galloway. After he joined forces with Benjamin Franklin in 1764 in order to convince the King to suspend the Penn family's proprietorship over Pennsylvania, he was voted out of office and would not be re-elected into office until the following year.

Speaker Galloway was chosen to represent Pennsylvania at the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia (at Carpenter's Hall) in September 1774 and used the opportunity to advocate against independence from Great Britain. In fairness, it wasn’t a difficult task. Except Massachusetts, where the Suffolk Resolutions were passed on September 9 by representatives from Boston and the rest of Suffolk County, none of the colonies were seriously considering independence yet. The Suffolk Resolutions declared the Intolerable Acts as illegal and urged for the creation of a separate government until they were repealed, advised the cessation of tax collections and trading with the British, and supported the creation of militias and appointing officers for them. Other counties throughout the colony passed similar resolutions. In October, the town of Worcester even declared the end of British rule. While similar sentiment was seen elsewhere in the colonies, they were generally isolated pockets and were not as influential in other colonies as in Massachuetts.

Alongside John Dickinson, John Jay, Edward Rutledge, and others, Galloway was among the conservatives in the First Continental Congress who believed that their task should be to create policies that would pressure Parliament to rescind the Intolerable Acts. Even within the wing, none of the other conservative delegates developed a plan like Joseph Galloway. What he proposed was the creation of an American parliament to act in tandem the British Parliament, which would consist of a crown-selected President-General and delegates popularly appointed by the colonies to terms of three years apiece. The Grand Council was to have a veto over the decisions made in the homeland on issues like taxation and trade. The initial proposal involved all twelve colonies with delegates at the Congress (all of New England and the Middle Colonies plus Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas) plus Georgia. This was not the first time a plan like this was proposed. It was initially done so 20 year earlier by his mentor, Benjamin Franklin, in Albany, New York as a means of defense against the French during the Seven Years War in North America.

Since early in the Congress, this was a debated issue which initially seemed to appeal to the majority of the non-radical delegates. It was not until Paul Revere of Massachusetts arrived in Phiadlephia on Swepember 16 with news of the Suffolk Resolutions. This made Galloawy’s Plan of Union become divisive in a way that it wasn’t before. While already appealing to the more radical members of Congress, the idea of liberation form British rule became more appealing to some of the more moderate Patriots, especially those from New England. Nevertheless, the debate over the Plan of Union lasted for several more weeks. The vote on the plan came on October 22, 1774. The delegates were polarized on the subject. The outcome was decided when a Patriot expected to vote against the measure changed his mind at the last minute and voted in favor of the Plan of Union. The voting prevailed in its favor, 6-5. In the meantime, the First Continetal Congress first saw the Peittion to the King on October 1, which formally called for a repeal of the Intolerable Acts. Its approval came on October 25 before it was amended and sent to Britain. Lastly, with Galloway’s Plan of Union approved, the colonies not in attendance here, East and West Florida, Georgia (the most likely to join), Nova Scotia, Quebec, and St. John’s were invited to the probable Second Continental Congress on October 26.

Last edited:

Any reason why they haven't invited a delegation from the colony of Newfoundland?

In real life, according to this, Newfoundland was not invited to the Second Continental Congress either. It's also important to note that Newfoundland didn't become part of Canada IRL until 1949. Furthermore, for clarification, St. John's is present-day Prince Edward Island.Any reason why they haven't invited a delegation from the colony of Newfoundland?

Here's a poll to help determine the fates of East and West Florida, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and St. John's:

www.strawpoll.me

www.strawpoll.me

Should East and West Florida, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and St. John's join the Union of British North America?

Vote Now! [All of them should] [None of them should] [One of them should] [Some of them should]

I can easily see the Floridas and Maritimes joining a Dominion somewhat soonish in the future - partly because they'd have no reason NOT to in time once they're built up more, but also because their first and majority Anglo settlers were actually American, and Nova Scotia in particular had some patriot sympathies during the American Revolution even if they amounted to a damp squib in practice. About the only reason they wouldn't immediately is they've only been British for a dozen years by this point and emptied out of their original Floridiano and Acadian (mostly, in that case) colonists and newfound Anglo-American colonists were busy establishing themselves.Here's a poll to help determine the fates of East and West Florida, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and St. John's:

Should East and West Florida, Nova Scotia, Quebec, and St. John's join the Union of British North America?

Vote Now! [All of them should] [None of them should] [One of them should] [Some of them should]www.strawpoll.me

Quebec's the one I can see staying out of it until it's more or less forced to join for whatever reason, whenever, in TTL's history.

That's definitely true about Nova Scotia. With regards to the Floridas, I thought the majority of the population there at the time of the outbreak of the American Revolution was still Spanish Catholic. So that could delay things. As far as Quebec goes, not only is it modern-day Quebec but also much of Ontario and the Old Northwest Territory (Great Lakes portion of what is now the Midwestern US).I can easily see the Floridas and Maritimes joining a Dominion somewhat soonish in the future - partly because they'd have no reason NOT to in time once they're built up more, but also because their first and majority Anglo settlers were actually American, and Nova Scotia in particular had some patriot sympathies during the American Revolution even if they amounted to a damp squib in practice. About the only reason they wouldn't immediately is they've only been British for a dozen years by this point and emptied out of their original Floridiano and Acadian (mostly, in that case) colonists and newfound Anglo-American colonists were busy establishing themselves.

Quebec's the one I can see staying out of it until it's more or less forced to join for whatever reason, whenever, in TTL's history.

You're probably right, but we'll just have to wait and see what happens and when it all happens.I expect the two main political factions of Whigs and Tories would eventually emerge as formal political parties, with the Whigs stronger in New England and the Tories stronger in Deep South (the Middle Colonies are swing regions).

Ah, pretty much everyone Spanish/Floridiano moved out of the Floridas in 1763 - it's why it eventually fell in American hands in due time, the loyalists moving in moved out in turn in 1783 but no Spaniards outside of garrison soldiers and administrators moved back, but now-patriot Americans came forth in the coming decades. Quebec as you put it is true, but I can completely see Ontario and the Northwest Territory westward being split off as Anglo-Americans move in.That's definitely true about Nova Scotia. With regards to the Floridas, I thought the majority of the population there at the time of the outbreak of the American Revolution was still Spanish Catholic. So that could delay things. As far as Quebec goes, not only is it modern-day Quebec but also much of Ontario and the Old Northwest Territory (Great Lakes portion of what is now the Midwestern US).

Threadmarks

View all 36 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter Twenty-Three: The UAC Parliamentary Elections of 1819 Chapter Twenty-Four: New World Problems, Old World Solutions Chapter Twenty-Five: A “Central” Continent Chapter Twenty-Six: An Independence Movement? Chapter Twenty-Seven: UAC Politics of the 1820s Chapter Twenty-Eight: An Early Period of Reform UAC Map Circa 1828 Chapter Twenty-Nine: More Reforms Across Europe

Share: