The Bourbon government had the great

merit of preserving our lives and subsistence,

a merit the present government can not claim.

We have neither personal nor political liberties.

-Neopolitan Deligate to the Italian Parlament, 1863

The Pauper: The Buildup to the Palermo Revolution

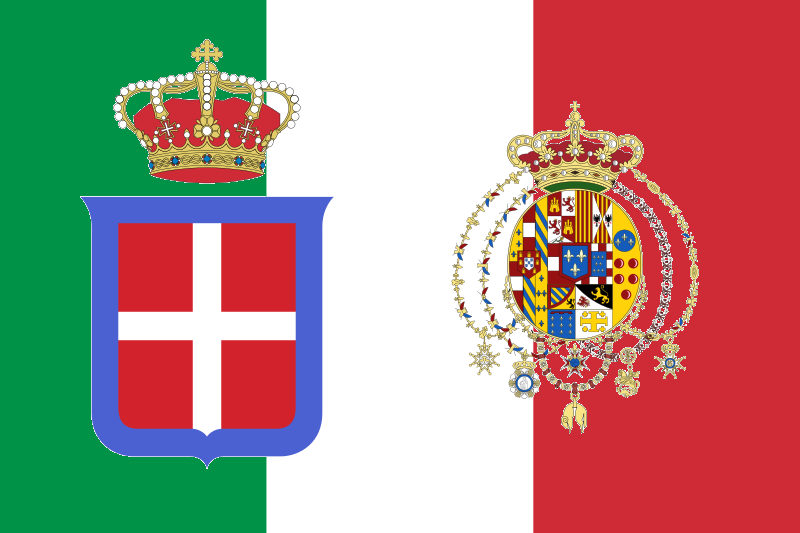

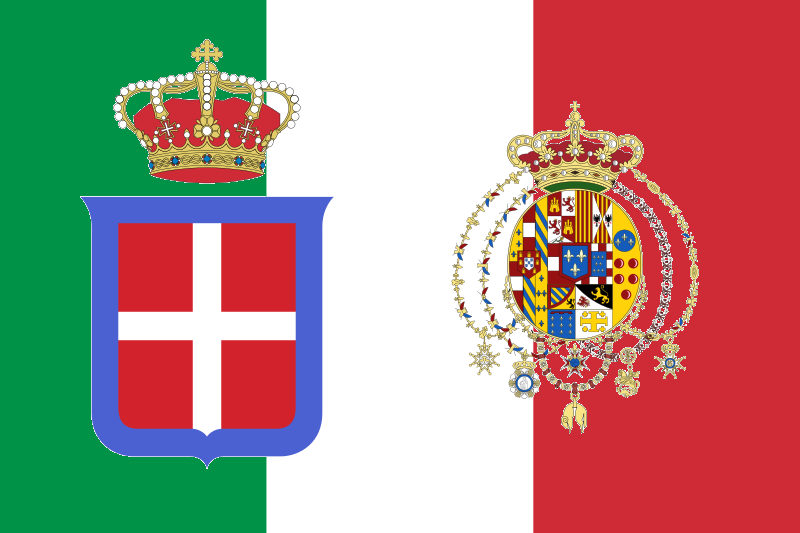

Mezzogiorini resistance to North Italian encroachment began essentially when Francis II surrendered his armies to Cialdini in Feburary of 1861. Physically isolated from the cutthroat commercial and military contests of Northern Italy by oceans and mountains and dominated together by a series of foreign overlords, the south of the Peninsula possessed a culture entirely alien to an intelligentsia raised in the mercantile traditions of Milan, Genoa, and Florence. Modest landowning elite, instead of being replaced by salaried bureaucrats appointed from the capital , were largely left to their own devises in dispensing justice and providing security provided the taxes came in on time in a continuation of centuries-old feudal relations with their distant sovereign. With little oversight or instruction from the political center, this system resulted in a series of unaffiliated and unofficial private police forces

; appointed by the local authorities to enforce their local laws under their unique local methods and codes of honors. These same communities had developed a deep dependency on the Church a source of education and civil services that would be provide by the State in many other parts of Europe: driven in part by regional nobles, pleading poverty, unloading the responsibility and the fact the churchs were largely stocked by local sons who cared deeply for their neighbors and childhood home. Most often compared to the charitable presentations of the Antebellum American South, the gap between this Southern paternalism and Northern dynamism had resulted in a similar difference in economic development by the time the region was integrated into a United Italy. In most of the major measures of industrialization and move into the market economy; railway and road millage, iron and steel production, capital saved up in banks, the regions north of Rome outpaced the regions south of it over 10 to 1, adding a material dimension to the yawning moral gap that existed between the two populations. While the half-century since the abolition of journalism had planted the seeds of change into the system: raising high customs barriers and state capital being loaned to prospective merchants and manufacturers who previously couldn’t find starting funds, the preservation and continued growth of the infant industries was still dependent on the protection of the Bourbon regeime from competition from the much better established forgien firms.

The conquest of the region by the Kingdom of Sardinia provided a devastating blow to this gradual adaption of society. Suddenly awoken from their sleepy isolation and dream of land reform, few peasants could have imagined what life really would be like under the dictates of Turin and had no way of any idea of how to integrate into their new reality. Virtually overnight, through the signing of a few papers, their markets were thrown wide open to constant trade with the better-capitalized northern firms. Cheap goods came flooding into port cities, undercutting the price of local workshops just as the Bourbon assets they might have turned to for their investment or liquidity loans disappeared into the new central treasury. The resulting downsizing and closures produced a flood of newly-minted vagabonds who, squeezed by rising food prices just as they saw those same ships carrying away grain for consumption by the very workers who’d stolen their jobs, naturally took to blaming the Italian administrators and upper-class migrants coming down to make personal fortunes for their situation. With no work to be had in the larger towns and the municipal sources of charity and support being transferred from the church and sympathetic local nobles to political appointees indifferent to local suffering, these former apprentices and artisans scattered over the countryside to try to make new lives for themselves: often forming gangs with former co-workers for the sake of mutual security and support.

Here, these urban dissidents found a similar simmering unrest among the farmers. Under the light hand of the Bourbon regime, the right to the use of common land and practice of small-holding had survived the death of de juro feudalism as a result of informal understandings between the peasentry and gentry. With the proceeds of their land being too low to afford to become absentee landlords or invest in a diversified income, the later had a material position that differed from their tendents only in scale rather than substance: living on, directly working with, and dependent on their estates. With that much more work to do and a greater trust in (and ability to verify) the locals, along with the fact that its simply harder to ignore the suffering of people you see every day, this produced a system of co-operative management that, while limiting the ability to shift from subsistence to commercial farming, had in a way acted as a guarantee of work, food, and shelter from the vagaries of markets. With annexation into the Kingdom of Italy, however, came the consolidation of these estates as a combination of rising taxes and divestment of Bourbon loyalists opened up previously divided landholdings for purchase by Northern speculators and a handful of already established large-estate owners. With this change had come a rapid shift for the spirit of the agreement to enforcement only by the letter, the prospect of profit by providing their new internal markets with raw material at much higher than pre-annexation prices driving the rapid enclosure of land and the removal of tolerance for indebtedness. Far from shrinking in the face of these strict physical boundaries, however, the peasantry responded with roiling anger to what they perceived as “robbery” of their long-standing rights without compensation.

Less apparent, but no less difficult to live with changes, affected the region across these class and ideological lines. Under the terms of the 1859 Casati Act, Mezzogiorini children, were forced off the fields of families, in desperate need of the free labor to help weather the imposition of new taxes and servicing of back-rent. Unlike the parochial schools of the prior era; who were sensitive to the seasonal agricultural needs and spoke fluently in the regional dialects, the superintendents placed in charge by the new regime were selected from those locals who could curry favor with the Piedmontese educational establishment and, thus, get their license validated. Adherents the policy of assimilation, which believed the creation of a united Italy required crushing independent regional identities by removing them from the youth, were deaf to protests against the hard-handed methods used in pursuit of this greater good. Physical punishment was meted out for speaking in Naplese or Sicilian rather than the Florentine dialect all lessons were held in, including the kinds of forced marches usually reserved for military discipline, and the removal of theological courses and prayer breaks left many parents objecting for the fate of their family’s souls. More agrecious, however, was the transfer of land grants held by the Church for the operation and building of schools to provincial authorities approved of by the Savoyards. Whereas in the past the excess profits of these lands would go back into the community in the form of charity and social services, now (like every other tax) the revenues went not to the needs of the poor but the priorities of the Turin government; removing a vital safety net for the poor farmers.

At first, this unrest only simmered as the two tracts of resistance competed rather than cooperated with one another. Bourbon loyalists, clericals, and cottagers who’d been kicked off their land by enclosure retreated into the hills to engage in the time-honored tradition of briganda

. A fact of life in most regions throughout the south, the

Briganda was the practice of young men lashing out against perceived injustice (weather political or simply from poverty) by engaging in raids on the estates of the elites and waylaying of overland trade. While in times of peace the views of these figures by peasant communities was mixed, during occupation they took on a celebrity status as the keepers of the fires of resistance by filling for the Italians the trope of the “Peasent Folk Hero” for the locals that figures like Robin Hood, Joan of Arc, the Minutemen held in other countries. The generals occupying the region, realizing the job of surpressing so many bandit parties would be extremely expensive, had enlisted the large landowners and merchantile bougious to enforce marshal law. As the few benefitiaries of the Savoyard reforms, they were only too happy to lend a hand in maintaining law and order in the countryside while the Italian authorities and their regular garrisons stayed in the cities. To carry out their authority, they recruited the rowdy bands of migrant urbanites as rural police: providing these potential recruits for the resistance with a legal way to earn and living and vent their frustrations in a way that dident undermine the status quo. During the early years of occupation, this practice of putting these two factions of marshal dissent against one another while maintaining the privlages (and thus loyalty) of the wealthy elite was successful in preventing the formation of a proper popular uprising. By the outbreak of the Fraternal War, while there remained deep and broad ideological and material distaste with the policies established by the unification and no small amount of nostalgia for the days of independence, the lack of resources and a leader who could bridge the gaps between the mixture of agrarian, clerical, protectionist-provencial , reformer, and Legitimatist factions which made up the anti-government forces had reduced violent resistance to the occasional show of force against villages suspected of aiding and supplying the brigandi or an exchange of gunfire between supply colums and ambushers trying to secure ammunition.

Crucial events occurred during the summer of 1866 which would lead to these tensions finally boiling over. The first was the passage of marshal law at the outbreak of the war, obliging the local garrisons to take direct control of enforcing the Legge Pica legislation of 1863 which mandated the death penelty to relatives and supporters of the

briganda . Until then the lands outside the patrol zones of each city were managed as they'd always been by the landlord,who was often willing to accept bribes in exchange for leiency and jealiously guarded his perogative against agents of the occupation.Post-

Pronunciamiento paranoia against former clients of Cialidini disrupted this delicate balance the Duke had set in place by raising suspicion against any armed faction outside Royal control which might attempt a coup against the Prime Minister in favor of their patron. Immediately upon the transfer of juristiction of the region to the Inspector-Generals from civilan administrators, an ultimatium was sent out to the companies at arms demanding they turn in their rifles or report fot integration into "official" Italian police and military units manned and lead by Northern officers. Within days, over 15,000 troops were in the field, declaring any man who refused to surrender his firearm a

brigand and thus subject to immediate execution.

If the intent of the military was to head off unrest in the region, they failed utterly. Infantry colums; largely made up of aged reservists as the veterans of the surpression and young patriotic conscripts had largely been transferred to the front, were ill suited to combating gureillas in the maze of narrow country lanes and shallow vallies of the Mezzogiorino landscape, which provided perfect hiding places for brigandi who'd been operating in them for years. Wherever the army appeared in strength, arms could simply be buried underground or in secret nooks of sympathetic locals; often in the graveyards and crypts of churches or old noble estates even the most secular commanders dident dare order their men to desicrate. Where troops were fewer, companies would openly resist efforts to confiscate their weapons or press them into service, often with the tact silent support of their employer. The fallout of losing the loyalty of the Gentry, who found the prospect of losing their own private police and thus independent authority unacceptable, deeply undermined the position of the military as they lost a previously vital source of trusted information: minor commanders now operating out of blind fear once stories of false leads directing units into traps started spreading.

Second was the fallout of a second, genuine

Pronunciamiento in Spain. An insurection on June 22 by troops in Madrid itself, lead by several high profile figures in the military, had only barely been surpressed by swift and direct action on the part of Prime Minister O'Donnell. Far from being rewarded for his loyalty to the regeime, however, Queen Isabella had reacted to the revolt by turning against both the liberals and moderates in her regeime: dismissing O'Donnell due to his perceived threat as head of the left-center Union-Liberal and replacing him with the stauch conservative Duke of Valencia. Disgusted by this betrayal, the commander was preparing to join the coup plotters such as John Prim (Hero of the Spainish-Moroccan War and commander of the Spainish expedition to Mexico in 62') in a self-imposed exile in France, having finally lost faith in the Queen's willingness to adopt needed financial and political reforms. Then, however, came a message from the Austrians and a figure with the Spainish court: a man who's very name carried the echo of liberal refining of Bourbon Absolutism with a promise of funds and a place of power in a prospective state if he could lend his and his supporter's expertice to a plan...

Antoine de Orlean