You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

For God, Crown, and Country: The Commonwealth of America.

- Thread starter Nazi Space Spy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 26 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XVIII: The Franklin Ministry & the Colombian collapse. Chapter XIX: The Northwest War & the French Revolution's early stages. Chapter XX: First in the Hearts of his Countrymen. Chapter XXI: The 1790 Federal Election Chapter XXII: Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite Chapter XXIII: Westward Ho! Chapter XXIV: The Haitian Revolution Chapter XXV: The early Industrial Revolution in America.Deleted member 9338

Doubtful looking at the initial mapQuestion will we annex Mexico

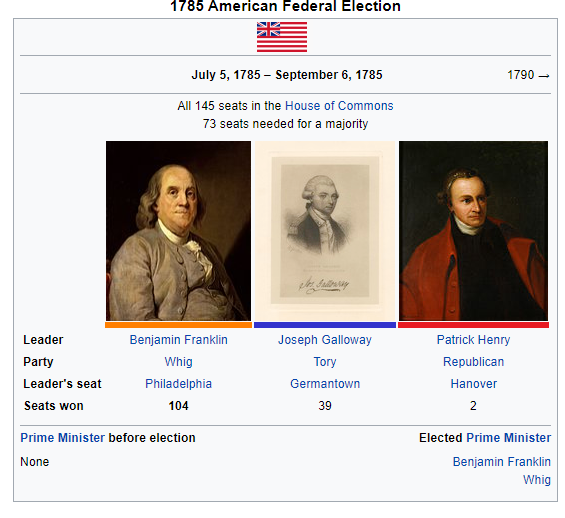

Chapter XVI: The 1785 Federal Election & the first Parliament.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

Upon the ratification of the Constitution, the Commonwealth of America immediately and officially became a new entity within the boundaries of the British Empire. When word reached Philadelphia that the Nova Scotia legislature had given the final ratification necessary for the Constitution to take effect, there was initially confusion over the next course of action. Though the Constitution specified the ratification process, it made no mention for the transition, and upon ratification in early 1785, went into effect. After three days of debate, Edmund Randolph of Virginia, who served as the Presiding Officer of the Convention and the last Continental Congress, simply went to the Governor-General and asked him to dissolve the convention. The Duke of York and Albany eagerly granted quest, sparking the first Federal election in American history. But the campaign did not come without its complications. Only a handful of provinces had outlined their parliamentary constituencies, with some provinces opting to use an at-large system instead. Also complicating the election was the fact that each province had their own standards for suffrage with different sets of voting pools and widely varying standards of citizenship. A handful of the ridings were known as “rotten boroughs" due to the fact that they contained virtually no constituents and were drawn specifically to benefit a particular candidate over the other.

The campaign’s early weeks were largely fought in the press, with aligned newspapers joining their preferred faction to broadside their opponents with increasingly negative smears. The first election was not fought on force of personality, nor was it even national in scale. The election was fought riding by riding, between individual candidates debating each individual riding’s unique needs. Though the election was fought almost entirely at the local level, it was clear to the candidates and voters who were the two leading contenders to form a government. Both came from the Whig faction, and both shared a longstanding animosity between the two men who clashed personality wise as they did politically. Their names were John Adams (a lawyer from Boston) and Thomas Jefferson (a Virginia legislator); whereas Jefferson championed a government "for and by the people," Adams saw the role of forming a government as a task done not for the public but rather the King.

The tone of the election turned brutally vicious as the cycle wore on, with political and personal attacks being hurled liberally. The chief Tory. Joseph Galloway accusing Patrick Henry of being a “republican” and “an agent of anarchy,” while other supporters of the Tory faction spread rumors that Jefferson had secretly converted to Catholicism. The Whig party’s supporters were equally inclined to the muckraking, and Henry himself delighted in publishing his own responses to Galloway. Writing that Galloway had no consideration for the rule of law, Henry warned voters of tyranny and sardonically predicted a future of “full taxation with no representation.” Though their support among the citizens was more or less split evenly, going into the campaign it was clear that the election was just as much charged by regionalism as it was by philosophy. In some ridings, the campaigns were even more acrimonious than the broader federal election. A number of well-known figures, including John Adams, George Clinton, Benjamin Franklin, Albert Gallatin, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, James Madison, and George Washington all stood in their respected ridings, and were met by varying level of opposition.

The parliament assembled after a quorum was reached in mid September as newly elected members trickled into Pennsylvania; the House and Senate would find a temporary home in Commonwealth Hall, the former Pennsylvania State House where the Continental Congresses met. The formation of a government was the immediate priority; though the Whig faction held an overwhelming and absolute majority, it remained uncertain if the party's factions could be united. Both Jefferson and Adams were nominated by the divided and diverse Whig caucus, but neither man could hold a majority of their own party, much less the whole House.

The parliament assembled after a quorum was reached in mid September as newly elected members trickled into Pennsylvania; the House and Senate would find a temporary home in Commonwealth Hall, the former Pennsylvania State House where the Continental Congresses met. The formation of a government was the immediate priority; though the Whig faction held an overwhelming and absolute majority, it remained uncertain if the party's factions could be united. Both Jefferson and Adams were nominated by the divided and diverse Whig caucus, but neither man could hold a majority of their own party, much less the whole House.

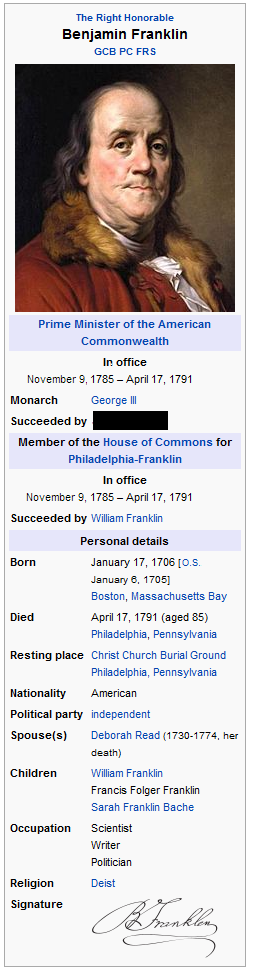

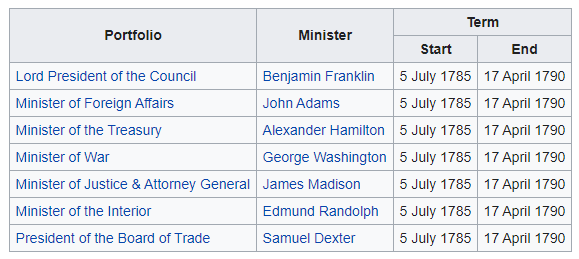

Benjamin Franklin today is remembered as “the first citizen” and “the father of the Commonwealth" in the public memory. Indeed, his image today is irreversibly associated with the ideals and guiding philosophy that led to the creation of the Commonwealth, even though politics were but a tiny slice of his long career as a man of letters, a journalist, an author, scientist, and philosopher. Franklin, after his role in establishing the Commonwealth, was looking forward to retiring from public life. However, he was so widely esteemed in his hometown of Philadelphia that no candidate dared to stand for the House of Commons from the city. As a result, his neighbors elected him the MP from the city, a position Franklin begrudgingly agreed to accept only because of the convenient nature of Philadelphia’s status of the capital. Despite his advanced age, Franklin himself was put forward as a compromise that almost the entirety of the parliament could agree upon. Stepping into office under the title “Lord President of the Council,” Franklin immediately set out to establish a more organized bureaucracy. Across the water in Britain, there were a plethora of departments, ministries, and titles that often shared responsibilities. One such example was the existence of two separate Foreign Ministers, the Secretaries of State for the Northern and Southern Departments, who handled diplomatic affairs with the Protestant and Catholic states respectively. In the first two months of the First Parliament, the Administration Act of 1785 was rapidly passed. This created the “Federal Council,” to be filled with Ministers for Foreign Affairs, Finance, War, Justice, and the Interior.

It was John Adams who was named Minister of Foreign Affairs, partially due to his reputation in London as a respected moderate who sought simultaneously to retain the position of America within the British colonial empire while also asserting the autonomy of the Commonwealth. Alexander Hamilton was named Minister of the Treasury as a result of his experience in both commerce and public life. The Minister of War was a Virginian MP and a respected former British officer named George Washington, known widely for his exploits during the Seven Years War. Known in Philadelphia as "Unionist Whig," these three appointees (particularly Adams and Hamilton) found themselves at odds with "Democratic Whigs," a coalition of agrarian yeomen farmers and southern patriots who were in favor of the constitution and confederation. To bridge the divide before the Whig's factional power, Franklin named James Madison as the first Minister of Justice. Thomas Jefferson declined to take on the role of Minister of the Interior, arguing that the ministry itself was tasked with objectives that ran counter to his proposed "Bill of Rights," which would devolve the responsibilities of such a ministry to the provincial level. Edmund Randolph was instead appointed to the position, resulting in the regional balance Franklin sought.

The ascension of Franklin to the premiership propelled the American Commonwealth onto the world stage as a semi-sovereign entity, the first of its kind in history and the dominant presence of North America, expanding from the Atlantic to the Mississippi River. But there were many challenges ahead and abroad; discontent simmered in the French capital of Paris while hostile bands of indigenous warriors watched encroaching westward expansion in the frontier forest. In such unprecedented times, only a man as wise as Franklin could've been trusted to navigate the Commonwealth through the trying times ahead.

The ascension of Franklin to the premiership propelled the American Commonwealth onto the world stage as a semi-sovereign entity, the first of its kind in history and the dominant presence of North America, expanding from the Atlantic to the Mississippi River. But there were many challenges ahead and abroad; discontent simmered in the French capital of Paris while hostile bands of indigenous warriors watched encroaching westward expansion in the frontier forest. In such unprecedented times, only a man as wise as Franklin could've been trusted to navigate the Commonwealth through the trying times ahead.

The campaign’s early weeks were largely fought in the press, with aligned newspapers joining their preferred faction to broadside their opponents with increasingly negative smears. The first election was not fought on force of personality, nor was it even national in scale. The election was fought riding by riding, between individual candidates debating each individual riding’s unique needs. Though the election was fought almost entirely at the local level, it was clear to the candidates and voters who were the two leading contenders to form a government. Both came from the Whig faction, and both shared a longstanding animosity between the two men who clashed personality wise as they did politically. Their names were John Adams (a lawyer from Boston) and Thomas Jefferson (a Virginia legislator); whereas Jefferson championed a government "for and by the people," Adams saw the role of forming a government as a task done not for the public but rather the King.

The tone of the election turned brutally vicious as the cycle wore on, with political and personal attacks being hurled liberally. The chief Tory. Joseph Galloway accusing Patrick Henry of being a “republican” and “an agent of anarchy,” while other supporters of the Tory faction spread rumors that Jefferson had secretly converted to Catholicism. The Whig party’s supporters were equally inclined to the muckraking, and Henry himself delighted in publishing his own responses to Galloway. Writing that Galloway had no consideration for the rule of law, Henry warned voters of tyranny and sardonically predicted a future of “full taxation with no representation.” Though their support among the citizens was more or less split evenly, going into the campaign it was clear that the election was just as much charged by regionalism as it was by philosophy. In some ridings, the campaigns were even more acrimonious than the broader federal election. A number of well-known figures, including John Adams, George Clinton, Benjamin Franklin, Albert Gallatin, Alexander Hamilton, Patrick Henry, James Madison, and George Washington all stood in their respected ridings, and were met by varying level of opposition.

Benjamin Franklin today is remembered as “the first citizen” and “the father of the Commonwealth" in the public memory. Indeed, his image today is irreversibly associated with the ideals and guiding philosophy that led to the creation of the Commonwealth, even though politics were but a tiny slice of his long career as a man of letters, a journalist, an author, scientist, and philosopher. Franklin, after his role in establishing the Commonwealth, was looking forward to retiring from public life. However, he was so widely esteemed in his hometown of Philadelphia that no candidate dared to stand for the House of Commons from the city. As a result, his neighbors elected him the MP from the city, a position Franklin begrudgingly agreed to accept only because of the convenient nature of Philadelphia’s status of the capital. Despite his advanced age, Franklin himself was put forward as a compromise that almost the entirety of the parliament could agree upon. Stepping into office under the title “Lord President of the Council,” Franklin immediately set out to establish a more organized bureaucracy. Across the water in Britain, there were a plethora of departments, ministries, and titles that often shared responsibilities. One such example was the existence of two separate Foreign Ministers, the Secretaries of State for the Northern and Southern Departments, who handled diplomatic affairs with the Protestant and Catholic states respectively. In the first two months of the First Parliament, the Administration Act of 1785 was rapidly passed. This created the “Federal Council,” to be filled with Ministers for Foreign Affairs, Finance, War, Justice, and the Interior.

It was John Adams who was named Minister of Foreign Affairs, partially due to his reputation in London as a respected moderate who sought simultaneously to retain the position of America within the British colonial empire while also asserting the autonomy of the Commonwealth. Alexander Hamilton was named Minister of the Treasury as a result of his experience in both commerce and public life. The Minister of War was a Virginian MP and a respected former British officer named George Washington, known widely for his exploits during the Seven Years War. Known in Philadelphia as "Unionist Whig," these three appointees (particularly Adams and Hamilton) found themselves at odds with "Democratic Whigs," a coalition of agrarian yeomen farmers and southern patriots who were in favor of the constitution and confederation. To bridge the divide before the Whig's factional power, Franklin named James Madison as the first Minister of Justice. Thomas Jefferson declined to take on the role of Minister of the Interior, arguing that the ministry itself was tasked with objectives that ran counter to his proposed "Bill of Rights," which would devolve the responsibilities of such a ministry to the provincial level. Edmund Randolph was instead appointed to the position, resulting in the regional balance Franklin sought.

If Franklin has his way the national bird of the American Commonwealth is the Turkey.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

Is there any holiday more patriotic than Thanksgiving? 😂If Franklin has his way the national bird of the American Commonwealth is the Turkey.

Though, to be honest, having America’s symbol be a turkey could be a small way to make this America not simply be a somewhat more British United States. And I haven’t seen many timelines on this site where that happens.Is there any holiday more patriotic than Thanksgiving? 😂

And I also agree that with the Fourth of July either not existing or having a reduced importance to the Commonwealth that Thanksgiving could take its place as a holiday symbolizing the nation’s heritage. Even if you were just joking it still makes sense.

Last edited:

Chapter XVII: The Colombian Revolution

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

Though the British were able to pacify the American colonies through the process of confederation, the Spanish were less fortunate. The root of the Colombian Revolution reached back to the years following the Seven Year's Wars conclusion, when Spain and France found themselves defeated and in debt. King Charles III of Spain ordered a more streamlined approach to managing the colonies, which resulted in the King's ministers in Madrid taking a greater interest in the mismanaged Viceroyalties in the New World. This was met with hostility from the Criollo elite, many of whom had been avoiding taxation while reaping the enormous wealth they generated through the use of slave labor on their plantations. The New World's Spanish colonies had a vibrant middle class of Mestizos who sought greater economic access, which the Criollo elites feared would threaten their wealth. This put the two classes into conflict while the poor, the indigenous, and the enslaved yearned for freedom in general.

In 1781, the Spanish government's attempt to streamline revenue resulted in an overhaul of the taxation system that had been employed by the colonial authorities for centuries. Riots broke out in cities up and down Latin America from Mexico to La Platta. The first major incident of insurrection broke out in the Captaincy-Generalship of Chile's provincial capital of Santiago. Spurred on by radical enlightenment idealism, three plotters (Antonio Gramussett, Antonio Berney, and Jose Antonio de Rojas) began conspiring to launch a revolution against the colonial authorities with the goal of establishing an independent republic in which wealth was shared by all and in which slavery was abolished. Using a printing press, the three men began publishing a series of anonymous pamphlets that agitated against the colonial elite and the Spanish government. It only took a few weeks before public dissension boiled over, with a mob of angry Mestizos and peasants marched on the central plazza of the city of Santiago, where they were met by Spanish soldiers who opened fire on the mob. Eleven people were killed, and the three conspirators were eventually arrested, tried, and executed for their role in the unrest. Though their executions were meant to ward off further anti-government activity, in reality it only served to further proliferate their message.

The next incident occurred in Peru, where Tupac Amaru II, an indigenous leader, led an uprising of Quechua and Mestizo peasants which resulted in the slaughter of Spanish and European settlers living throughout the Viceroyalty of Peru. As was the case in Chile, the colonial leadership in Lima were eventually able to suppress and then capture Tupac Amaru himself only after the large scale mobilization of Spanish forces in the region. Tupac Amaru's brutal execution by quartering was meant to send a message to his band of followers (who numbered in the tens of thousands), but the rebellion continued in the Andean mountains for months following his execution. Though the Spanish were eventually able to put down the last lingering footprints of the revolt, the resentments generated by the conflict would remain rooted in colonial society for years to come.

In New Grenada, taxation led to large scale rioting in cities across the region, which exploded into full blown revolt when protesters seized an armory in Bogota and declared themselves to be the new colonial government. They sent a delegation to Cartagena to present their case for a new civilian legislature and a voice in government, but were declined a meeting with the Viceroy, who instead chose to deploy troops to Bogota. Having turned back this attempt to recapture the lightly defended city in the Andes, the rebellion in New Grenada caught the attention of many in North America and Europe. Watching the developments with great enthusiasm was Francisco Miranda, a Spanish military officer with enlightenment values who sympathized with the Latin cause. After a fourth revolt broke out in Mexico following the expulsion of the Jesuits, Miranda leapt at the chance to put his military experience to work. Leaving his post in Havana, Cuba bound for his native Caracas, Miranda became acquainted with a Frenchman known as the Marquis de Lafayette, a 24 year old officer in the French military who had sympathized with the rebel cause in Spanish America.

Francisco de Miranda

The two would make their way together to Bogota, where they quickly ingratiated themselves with the mostly unorganized rebel militias that had occupied the city. Under their command, Miranda and Lafayette transformed this force into a relatively professional force. As Spanish troops gathered in Caracas and Cartagena, the leaders of the Bogota revolt found themselves in an uncertain position; with the rebellion being centered around taxation, many of their leaders were directionless as to how to move forward. Taking command, Miranda and Lafayette led the rebel army to Sabanalarga, where the Spanish army massed in preparation for a counter attack on Bogota. The battle ended in a total route of Spanish forces, scattering their only opposition as they marched on Cartagena. The Spanish garrison there ultimately were forced to surrender, allowed to leave only after surrendering their muskets, artillery, and uniforms to the victorious rebels.

While Miranda and Lafayette both called for Colombia to declare itself independent of Spain, they remained in the minority as most rebels were not yet fully committed to such a radical end. But circumstance would quickly shift the public's perception. It began in Venezuela's slaves, inspired by events to the west, took up arms against their masters and declared themselves followers of the Chilean, Peruvian, and Colombian revolts. Their brutal killings of slave owners drove thousands of Criollos into the arms of their Spanish overlords, becoming reactionary loyalists in response to the events taking place around them. The Quechua tribes that rebelled in Peru continued to keep Spanish forces bogged down with guerrilla warfare, which further alienated some Criollo elites from backing Miranda's rebellion. Despite the efforts of Miranda to expand his support among the upper classes, his movement by 1782 had become intertwined with the narrative of a class struggle, and the Spanish government in Madrid saw an opportunity to reset the campaign in what they insisted was still the colony of New Grenada. A small armada of reinforcements was dispatched to Caracas, and news of the arrival of the fleet spread across the continent in the months that followed. This sparked a new revolt in Buenos Aires, the capital of the Viceroyalty of La Plata, which resulted in the Viceroy being packed off to Spain and a civilian interim government taking his place. With an insurgency in Peru separating the southern colonies off from events in Colombia, the revolt in La Plata grew as peasants and Mestizos rallied around their cause. The Spanish army stationed in Chile ever since the "revolt of the three Antonios" was mobilized to march on Buenos Aires, but were met on the battlefield by the latest rebel army on the Patagonian plains, where they were repelled at great human cost.

The Marquis de Lafayette.

But a chain of events would soon be put in motion; though the British had claimed and briefly occupied the Falkland Islands, the uninhabited islands in the south Atlantic remained unsettled. With Buenos Aires under the control of local rebels who were lightly armed, poorly trained, and unaffiliated with Miranda's forces, the Spanish saw an on opportunity to stop the spread of the rebellion into the southern colonies of Chile and La Plata. A second Spanish fleet set sail for the Falklands, which King Charles III claimed for Spain, in order to establish a military base from which to stage an intervention against the rebellion. When word of this reached London, the British government of William Pitt the Younger sought a declaration of war from Parliament in 1782, and the British navy was sent into action. The Anglo-Spanish War quickly expanded, with King Louis XVI of France honoring the nation's long standing alliance with Spain, and the French Navy set out across the Atlantic to match the British on the high seas.

It took only a few months for the British to establish a blockade around the Spanish Main and the Falkland Islands, which were retaken by British Marines in a swift and successful operation. The British intervention emboldened the rebels there, who successfully laid siege to Caracas, which gave Miranda's army full control of New Grenada. His forces than marched south, hoping to link up with the lingering Quechua insurgency in Peru in order to unite with the rebels in La Plata. French attempts to push the British fleet back into the Atlantic resulted in a string of British victories off the Colombian coasts, and while Miranda spent 1783 and 1784 pushing through Peru as fierce fighting continued. The confederation of Britain's colonial possessions in 1785 saw the Commonwealth of America enter the war, opening a new theater as the fighting continued.

Spanish troops in New Orleans.

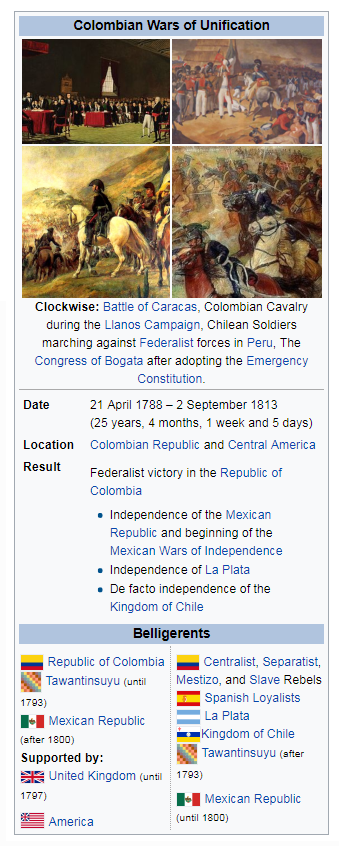

In 1787, after six years of conflict, the Treaty of London was signed. With the exception of their island possessions like Cuba and Puerto Rico, Spain was stripped of all of their continental holdings. Louisiana was handed over to the Americans, while Colombia was recognized as an independent nation. France was also forced to give up Saint Pierre and Miquelon to Britain, and the Falkland Islands were similarly awarded to Britain. It took only a year for Miranda to concentrate power in Colombia, which would plunge the continent into war once again....

Credit to @Oryxslayer for his work in the original Yankee Dominion thread. The Colombian Revolution and the infoboxes for it are taken from the original project, of which Oryxslayer was a valued and important contributor to.

Ficboy

Banned

I'm betting that there is still a French Revolution and a Napoleon in this timeline given the territory that the Commonwealth of America controls is all of OTL USA and Canada minus the Southwest portions of the former which is part of Mexico instead. Not to mention the Louisiana Territory and it's states are also part of the Commonwealth of America (COA). It also helps that Gran Colombia got it's independence from Spain with the help of Britain and America.

As far as slavery is concerned, since the America is more or less a Dominion akin to Canada, Australia and New Zealand and Britain will gradually abolish slavery in 1833 you can bet that the institution will be peacefully phased out without civil war and compensation to the slave owners (mostly Southern and some Northern). Equal rights for Blacks and other groups will take much longer though but nowhere near as bad as OTL.

Anti-Catholicism will still linger on in America per OTL since Britain was notoriously hostile towards them but in time emancipation will come in 1829.

As far as slavery is concerned, since the America is more or less a Dominion akin to Canada, Australia and New Zealand and Britain will gradually abolish slavery in 1833 you can bet that the institution will be peacefully phased out without civil war and compensation to the slave owners (mostly Southern and some Northern). Equal rights for Blacks and other groups will take much longer though but nowhere near as bad as OTL.

Anti-Catholicism will still linger on in America per OTL since Britain was notoriously hostile towards them but in time emancipation will come in 1829.

I expect Colombia to disintegrate if it doesn't get a grip on things quickly.

That is one big country to manage, given the level of communication and speed of travel at the time.

That is one big country to manage, given the level of communication and speed of travel at the time.

I agree. There's no way a country spanning from California to the Strait of Magellan would stay in one piece. Gran Columbia was nowhere near as big and it failed.I expect Colombia to disintegrate if it doesn't get a grip on things quickly.

That is one big country to manage, given the level of communication and speed of travel at the time.

Chapter XVIII: The Franklin Ministry & the Colombian collapse.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

The Premiership of Benjamin Franklin was marked primarily overseas by the American intervention in the Colombian War and capture of New Orleans and Louisiana, but he faced plenty of battles at home regardless. Though the majority of the Commons identified as Whigs, the diverse nature of the MPs under this umbrella ensured that Franklin would be forced to craft a government that had to bridge both ideological and regional divides. In spite of the compromise that gave birth to the first cabinet, it was remarkable in the fact that Franklin did not make one single replacement during his five years in office. Though intended to be only a temporary government, Franklin's five years in office saw political tranquility in Philadelphia that was based primarily out of respect for Franklin.

There were of course disagreements - the first and most notable of which involved the American intervention in the Latin American conflict; seeing the Commonwealth as subservient to the Crown in London, but not the parliament, Franklin called upon the parliament in Philadelphia to formally declare war on France and Spain upon the first sitting of the legislative body. In seeking this declaration, the Prime Minister was hoping to enter the conflict on America's own terms rather than wait for authorities in London to challenge the American constitution as part of an effort to micromanage the Commonwealth's military from London. The decision to enter the war was not without it's critics; Thomas Jefferson, perhaps the most influential Whig not in the government, warned that Franklin was risking America's fragile autonomy, and argued that British intervention was based out of pure opportunism.

There were of course disagreements - the first and most notable of which involved the American intervention in the Latin American conflict; seeing the Commonwealth as subservient to the Crown in London, but not the parliament, Franklin called upon the parliament in Philadelphia to formally declare war on France and Spain upon the first sitting of the legislative body. In seeking this declaration, the Prime Minister was hoping to enter the conflict on America's own terms rather than wait for authorities in London to challenge the American constitution as part of an effort to micromanage the Commonwealth's military from London. The decision to enter the war was not without it's critics; Thomas Jefferson, perhaps the most influential Whig not in the government, warned that Franklin was risking America's fragile autonomy, and argued that British intervention was based out of pure opportunism.

The human toll of the conflict was matched by it's economic toll; the advent of the war resulted in American trade with France immediately ceasing, increasing the Commonwealth's economic dependence on Britain. This led to discontent among the merchant class, many of whom felt disconnected and unconcerned with the conflict raging in South America. In an effort to organize and expand the Commonwealth's economy, Finance Minister Alexander Hamilton compiled the Report on the Public Credit over the course of the first few months of the Franklin government. The plan argued for the federal assumption of the provincial debts, which would be paid off from the Treasury. While the northern provinces backed the debt assumption proposal, the southern provinces demanded exemption, claiming that such a plan would take more revenue from their coffers than it would debt. A consensus among the Whig majority supported a compromise in which the combined debt would be paid off through income generated by tariffs, but some, including James Madison warned that complications could arise from such a plan. Noting that France was the second largest trading partner with the Commonwealth in the lead up to confederation, Madison warned that such tariffs would fail to produce enough revenue to cover the payments. But his efforts proved to be fruitless; the House of Commons passed the National Debt Act of 1786 by a vote of 89-56, which was followed by another vote in the Senate which likewise approved the plan. Franklin implemented the program upon the legislation receiving the ascent of the Governor-General, and the debt amalgamation proceeded as planned.

Afterwards, Hamilton argued that the next step was to charter a central bank, a proposal which could fund economic development and internal improvements, which would lead to increased financial independence on London. This proposal was met with even greater skepticism than the debt assumption plan, and James Madison argued that a plan would require a common currency, which he feared would threaten provincial autonomy on fiscal affairs. Furthermore, the Virginian Minister of Justice claimed that the Bank would lead to an increase in corruption, though Hamilton dismissed this claim and countered in the House that the Constitution permitted the Congress to coin currency. Following extensive debate in the House of Commons, the Bank of America Act of 1786 was passed by a narrower than anticipated margin of 84-61. The Senate, which had previously backed the first stage of Hamilton's plan, was similarly skeptical. Ultimately, it cleared the Senate after a vote of 20-14, and the Governor-General approved the legislation. The American Dollar would result, being issued by the bank as the national currency. The governance of the bank would be conducted by four appointed commissioners approved by the Senate, while the American Board of Trade would chose a Governor to preside as the executive of the institution.

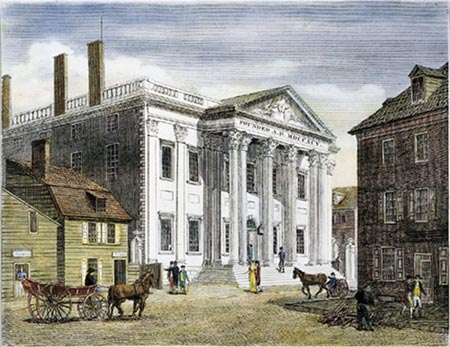

The Bank of America headquarters in Philadelphia.There was also the judiciary to establish; the Judiciary Act of 1786 remedied this by creating a Supreme Court that'd be led by a Chief Justice and eight Associate Justices. A federal judiciary consisting of district and appellate courts would also be established in order to ease legal disputes between provinces, with the House and Senate passing the bill quickly in order to strengthen the internal unity of the Commonwealth. The Prime Minister nominated nine Justices (three for each region of the country for geographic balance) who were quickly confirmed, with New York's John Jay being appointed Chief Justice of the highest court.

The Federal Lands Act was implemented in 1786; clearing Congress with ease, the act organized three territories under American jurisdiction. They included the Indiana Country, which was the land south of the Ohio River, the Ohio Country, which was the territory north of the Ohio River, and lastly, the Hudson Bay territory, which was controlled and regulated by the Board of Trade rather than the Interior Ministry. As the previous prohibition on settlement beyond the Appalachians had been repealed, there was nothing stopping thousands of settlers from crossing the Cumberland Gap in order to settle the western frontier. The parliament in Philadelphia passed the Indian Commerce Act of 1787 that year, which prohibited the sale of Indian land to private individuals without the consent of the parliament, as an attempt to balance out the population. The legislation also reserved the federal government's right to regulate commerce in federal territories.

While in the Indiana Territory, the Francophone, indigenous, and Anglo populaces were able to maintain a strained peace, the Ohio Country saw more conflict. The conflict's early stage began when British redcoats were withdrawn from the territory in the aftermath of confederation, and for two years the territory was largely unregulated and unorganized. When American forces were eventually deployed to occupy several of the abandoned British forts in the Ohio Country, there was a large increase in American settlement in the region. This was primarily due to the added security provided by these new American garrisons, but sparked tensions with indigenous leaders who felt threatened by encroachment. The tribal leaders repeated attempts to negotiate a moratorium on western settlement, but were largely ignored by Interior Minister Edmund Randolph, who saw no constitutional basis for such a prohibitive measure. As their pleas fell on deaf ears, the Lenape and Miami tribes began raids on settlements, massacring anyone who stood in their way. When word of such attacks reached Philadelphia, Minister of War George Washington ordered the army to begin cobbling together an expeditionary force to settle the unrest once and for all.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In Colombia, the fires of war still smoldered; in Mexico, the revolution turned from independence from Spain to independence from Miranda. This was quickly achieved, with the vast majority of rebels favoring independence from either state. La Plata was similarly concerned about the ambitions of the Colombian leader, and prepared for an eventual invasion from Peru by Miranda's army. Styling himself "President of Colombia," Miranda claimed the whole of New Spain, from Patagonia to Mexico, as his domain. Yet in reality, he controlled merely the regions of New Granada and parts of Peru. A Congress was convened in Lima, where a broad array of delegates gathered in order to hammer out a consistent vision as to how to move forward. But all that was achieved by this Congress was an agreement to accept the terms of the Treaty of London, which officially brought the war with Spain to a final conclusion. Afterwards, the convention fell into chaos as various factions and competing interests began to bicker over the next step forward. When the Lima Congress failed to move forward with legislation declaring de Miranda as the President of Colombia, he used the military to forcibly close the Congress. His opponents across the ideological spectrum took up arms as Mexico, Chile, and La Plata declared their independence from Colombia.

In Colombia, the fires of war still smoldered; in Mexico, the revolution turned from independence from Spain to independence from Miranda. This was quickly achieved, with the vast majority of rebels favoring independence from either state. La Plata was similarly concerned about the ambitions of the Colombian leader, and prepared for an eventual invasion from Peru by Miranda's army. Styling himself "President of Colombia," Miranda claimed the whole of New Spain, from Patagonia to Mexico, as his domain. Yet in reality, he controlled merely the regions of New Granada and parts of Peru. A Congress was convened in Lima, where a broad array of delegates gathered in order to hammer out a consistent vision as to how to move forward. But all that was achieved by this Congress was an agreement to accept the terms of the Treaty of London, which officially brought the war with Spain to a final conclusion. Afterwards, the convention fell into chaos as various factions and competing interests began to bicker over the next step forward. When the Lima Congress failed to move forward with legislation declaring de Miranda as the President of Colombia, he used the military to forcibly close the Congress. His opponents across the ideological spectrum took up arms as Mexico, Chile, and La Plata declared their independence from Colombia.

In response, Miranda rallied his forces and moved south, leaving the Mexican rebels to take control of the former Spanish Viceroyalty. Marching from Lima southward, local militias under the control of provincial politicians who acted as dignified warlords awaited their arrival. The lack of Spanish control of trade in Mexico opened up their markets to American commerce, which resulted in a rapid uptick in trade and public interest in Latin America. With Miranda cutting his losses as moving southward, Foreign Minister John Adams saw an opportunity to strengthen Mexico's hand and prevent the massive Colombian state from growing to be a potential threat in the future. This came in the form of selling gun powder, muskets, and artillery to Mexico in exchange for a wide variety of products, including gold, in return.

Though the Latin American revolutions were primarily a separate series of successful revolts, Miranda's ego had grown with his reputation, and he had begin to envision himself as "El Liberator" of the continent. Marching on La Plata, Miranda's forces were met near the outskirts of Corrientes by a hastily assembled military force sent northwards; the Colombian army was an exhausted and depleted force of troops who had trudged through both thick tropical forests as well as arid deserts in the Chaco region, only to loose a significant amount of men to disease along the way. The battle of Corrientes would be a defining moment in the history of South America, with the Colombian attack collapsing after Miranda himself was injured by a stray musket ball to the shoulder. Limping back to Lima in retreat, the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata was declared in the aftermath of the battle. Chile, which was a hot bed of Spanish loyalism, was isolated from these events by geography. Bordered by ocean to the west, and mountains to the east, the Spanish remained in control of Chile from their capital of Santiago and insisted that the terms of the Treaty of London only applied to the territory of New Grenada. For now, Chile remained in the hands of Madrid as events in France and Spain began to draw the world's attention.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Again, credit for @Oryxslayer for fleshing this part of the Yankee Dominion out. Up next is the ATL version of the French Revolution.

The human toll of the conflict was matched by it's economic toll; the advent of the war resulted in American trade with France immediately ceasing, increasing the Commonwealth's economic dependence on Britain. This led to discontent among the merchant class, many of whom felt disconnected and unconcerned with the conflict raging in South America. In an effort to organize and expand the Commonwealth's economy, Finance Minister Alexander Hamilton compiled the Report on the Public Credit over the course of the first few months of the Franklin government. The plan argued for the federal assumption of the provincial debts, which would be paid off from the Treasury. While the northern provinces backed the debt assumption proposal, the southern provinces demanded exemption, claiming that such a plan would take more revenue from their coffers than it would debt. A consensus among the Whig majority supported a compromise in which the combined debt would be paid off through income generated by tariffs, but some, including James Madison warned that complications could arise from such a plan. Noting that France was the second largest trading partner with the Commonwealth in the lead up to confederation, Madison warned that such tariffs would fail to produce enough revenue to cover the payments. But his efforts proved to be fruitless; the House of Commons passed the National Debt Act of 1786 by a vote of 89-56, which was followed by another vote in the Senate which likewise approved the plan. Franklin implemented the program upon the legislation receiving the ascent of the Governor-General, and the debt amalgamation proceeded as planned.

Afterwards, Hamilton argued that the next step was to charter a central bank, a proposal which could fund economic development and internal improvements, which would lead to increased financial independence on London. This proposal was met with even greater skepticism than the debt assumption plan, and James Madison argued that a plan would require a common currency, which he feared would threaten provincial autonomy on fiscal affairs. Furthermore, the Virginian Minister of Justice claimed that the Bank would lead to an increase in corruption, though Hamilton dismissed this claim and countered in the House that the Constitution permitted the Congress to coin currency. Following extensive debate in the House of Commons, the Bank of America Act of 1786 was passed by a narrower than anticipated margin of 84-61. The Senate, which had previously backed the first stage of Hamilton's plan, was similarly skeptical. Ultimately, it cleared the Senate after a vote of 20-14, and the Governor-General approved the legislation. The American Dollar would result, being issued by the bank as the national currency. The governance of the bank would be conducted by four appointed commissioners approved by the Senate, while the American Board of Trade would chose a Governor to preside as the executive of the institution.

The Bank of America headquarters in Philadelphia.

The Federal Lands Act was implemented in 1786; clearing Congress with ease, the act organized three territories under American jurisdiction. They included the Indiana Country, which was the land south of the Ohio River, the Ohio Country, which was the territory north of the Ohio River, and lastly, the Hudson Bay territory, which was controlled and regulated by the Board of Trade rather than the Interior Ministry. As the previous prohibition on settlement beyond the Appalachians had been repealed, there was nothing stopping thousands of settlers from crossing the Cumberland Gap in order to settle the western frontier. The parliament in Philadelphia passed the Indian Commerce Act of 1787 that year, which prohibited the sale of Indian land to private individuals without the consent of the parliament, as an attempt to balance out the population. The legislation also reserved the federal government's right to regulate commerce in federal territories.

While in the Indiana Territory, the Francophone, indigenous, and Anglo populaces were able to maintain a strained peace, the Ohio Country saw more conflict. The conflict's early stage began when British redcoats were withdrawn from the territory in the aftermath of confederation, and for two years the territory was largely unregulated and unorganized. When American forces were eventually deployed to occupy several of the abandoned British forts in the Ohio Country, there was a large increase in American settlement in the region. This was primarily due to the added security provided by these new American garrisons, but sparked tensions with indigenous leaders who felt threatened by encroachment. The tribal leaders repeated attempts to negotiate a moratorium on western settlement, but were largely ignored by Interior Minister Edmund Randolph, who saw no constitutional basis for such a prohibitive measure. As their pleas fell on deaf ears, the Lenape and Miami tribes began raids on settlements, massacring anyone who stood in their way. When word of such attacks reached Philadelphia, Minister of War George Washington ordered the army to begin cobbling together an expeditionary force to settle the unrest once and for all.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In response, Miranda rallied his forces and moved south, leaving the Mexican rebels to take control of the former Spanish Viceroyalty. Marching from Lima southward, local militias under the control of provincial politicians who acted as dignified warlords awaited their arrival. The lack of Spanish control of trade in Mexico opened up their markets to American commerce, which resulted in a rapid uptick in trade and public interest in Latin America. With Miranda cutting his losses as moving southward, Foreign Minister John Adams saw an opportunity to strengthen Mexico's hand and prevent the massive Colombian state from growing to be a potential threat in the future. This came in the form of selling gun powder, muskets, and artillery to Mexico in exchange for a wide variety of products, including gold, in return.

Though the Latin American revolutions were primarily a separate series of successful revolts, Miranda's ego had grown with his reputation, and he had begin to envision himself as "El Liberator" of the continent. Marching on La Plata, Miranda's forces were met near the outskirts of Corrientes by a hastily assembled military force sent northwards; the Colombian army was an exhausted and depleted force of troops who had trudged through both thick tropical forests as well as arid deserts in the Chaco region, only to loose a significant amount of men to disease along the way. The battle of Corrientes would be a defining moment in the history of South America, with the Colombian attack collapsing after Miranda himself was injured by a stray musket ball to the shoulder. Limping back to Lima in retreat, the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata was declared in the aftermath of the battle. Chile, which was a hot bed of Spanish loyalism, was isolated from these events by geography. Bordered by ocean to the west, and mountains to the east, the Spanish remained in control of Chile from their capital of Santiago and insisted that the terms of the Treaty of London only applied to the territory of New Grenada. For now, Chile remained in the hands of Madrid as events in France and Spain began to draw the world's attention.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Again, credit for @Oryxslayer for fleshing this part of the Yankee Dominion out. Up next is the ATL version of the French Revolution.

Last edited:

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

Colombia is definitely bound to splinter as noted, and that was detailed by Oryxslayer in the original project. I don't want to spoil anything, but there will be a French Revolution and a fascinating aftermath, also drafted by Oryxslayer. Next update will either be about the Northwest Indian War or France.

Colombia is definitely bound to splinter as noted, and that was detailed by Oryxslayer in the original project. I don't want to spoil anything, but there will be a French Revolution and a fascinating aftermath, also drafted by Oryxslayer. Next update will either be about the Northwest Indian War or France.

I'd be down with Columbia being able to keep the territory in former New Granada and Peru. It's just the sprawling empire from Mexico to Tiera del Fuego that stretched my suspension of disbelief to the breaking point. I like alternate history borders and a "Colombia" with the capital in Lima is interesting to me. Especially if Miranda is able to solidify his control over the territory the nation holds. Though hopefully South America will be better acquainted with democracy ITTL.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

I think your missing one key point here, though. Gran Colombia was never intended to be that large. It never had control of Mexico to begin with, merely a claim.I'd be down with Columbia being able to keep the territory in former New Granada and Peru. It's just the sprawling empire from Mexico to Tiera del Fuego that stretched my suspension of disbelief to the breaking point. I like alternate history borders and a "Colombia" with the capital in Lima is interesting to me. Especially if Miranda is able to solidify his control over the territory the nation holds. Though hopefully South America will be better acquainted with democracy ITTL.

Fair enough. Though I’m still keen on it possibly keeping what territory they currently hold.I think your missing one key point here, though. Gran Colombia was never intended to be that large. It never had control of Mexico to begin with, merely a claim.

Chapter XIX: The Northwest War & the French Revolution's early stages.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

Angered by the growth of American settlement in the Ohio Country, the Lenape and Miami tribes banded together to resist the changing demographics of their native region. Forming the Western Confederacy, the Shawnee, Lenape, Miami, and Wabash launched a series of raids on settlements throughout what is presently the province of Ohio. The survivors of these raids told lurid stories of brutality which were proliferated by the press, and Prime Minister Franklin quickly ordered the Minister of War to raise an army and establish security for settlers in the Ohio Country. Washington had unique experience, having fought the French in the region during the Seven Years War, and was willing to oversee the effort to quell the chaos once again. It took Washington just three months to cobble together an army of two thousand men who, though poorly trained, were prepared to do their part. Setting out from Pittsburgh, the army moved eastward towards down the shores of the Ohio River, establishing Fort Washington near what later became Cincinnati. Under the command of Josiah Harmar, the force marched for two weeks towards towards the key village of Kekionga, located near present day Fort Wayne, which would be named later on in honor of another hero of the same war. Harmar's legacy would be less victorious; as they neared the village, they were lured into an ambush where they were separated and scattered. While Harmar's army was able to regroup despite nearly 300 loses, they withdrew down the Wabash river away, giving Chiefs Little Turtle and Blue Jacket the opportunity to plan an offensive. Fort Recovery was constructed to provide a base of operations for the reduced army to operate from.

The winter of 1785-1786 was rough, with the soldiers under Harmar's command spending a cold winter there, sustaining further loses during this period. Meanwhile, scouts of the Western Confederacy stalked the region surrounding the Fort, waiting for the spring when another attack on Kekionga was sure to be launched. The Western Confederacy's own army swelled in size as more and more tribal warriors arrived to push back against the American presence. In March of 1786, another American push towards Kekionga was attempted as Washington, dissatisfied with Harmar's leadership, attempted to raise a second army to reinforce the men deployed in the Ohio Country. As a second army under the command of "Mad" Anthony Wayne, a brash general who held the confidence of Washington set out for Fort Recovery, the Harmar expedition fell apart when warriors surrounded and set fire to the fort; ultimately, a further four hundred men were massacred, including Harmar himself. The remaining force, halved and left exposed to the elements, made a retreat back to Fort Washington, where they awaited Wayne's men.

General Wayne was not content to await an attack; moving northward, Wayne first tracked west to both confuse enemy scouts while also drawing the bulk of the Western Confederacy's warriors away from Kekionga. Hooking east, Wayne's men moved with ruthless efficiency and stunned the indigenous inhabitants when Wayne's army emerged from the woods just miles away, overpowering the weak defenses and setting fire to the villages. Wayne's men then marched eastward knowing that the Western Confederacy would surely be in pursuit. As the native forces rallied their forces, Wayne prepared a trap for them at a place called Falling Timbers. Using the terrain to his advantage, the site was known to the indigenous peoples for a recent tornado which had knocked over trees, giving it's name. Drilling for the inevitable attack, Wayne's men positioned themselves at different levels among the bluff, giving them three lines to fire from which would cover the others as they reloaded. Naming the site "Fort Defiance," Wayne sent a message to Little Turtle and Blue Jacket by way of a native courier from a neutral tribe, which detailed his fort's location and ended with the haunting taunt: "come and take it."

The gambit worked; as indigenous insurgents crossed the Maumee river, they came under cannon fire followed by repeated volleys. In a battle that resembled Bunker Hill, two large charges by the Western Confederacy's warriors collapsed as the warriors sustained high casualties. As they retreated back across the river, the American force charged after them, exploiting a divide between the attackers, sending one group south and the other westward. Describing Wayne as "a black snake which never sleeps," Little Turtle called for the Confederacy to seek peace with the Commonwealth, which was obtained at the Treaty of Fort Washington, where several of the tribes in the Confederacy surrendered and accepted American sovereignty over the region. The war was the first true test of the Royal American Army, but victory was not yet fully achieved. Blue Jacket was continuing to present a threat to the total pacification of the Ohio Country, and Wayne was keen to eliminate the Western Confederacy entirely.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The crisis began in earnest when the King dismissed a popular bureaucrat named Jacques Necker, who maintained great support among the middle and merchant classes which comprised the Third Estate of the French government. Necker was able to secure nearly 75 million Francs in credit from French bankers and financiers, though the King was uninterested in reigning in his lavish lifestyle or granting more power to the Third Estate, which had traditionally been the weakest unit of the Estates General. To alleviate the crisis, a series of unpopular taxes were levied. However, the highly regressive nature of these taxes only further alienated the peasantry, who bore the bulk of the impact. Though Necker tried to broker a compromise, the opposition of the First and Second Estate made any resolution impossible. The King resolved to break the impasse by shutting down the Third Estate; he did so by ordering soldiers to their meeting hall (the three Estates met separately and were rarely called together) in order to physically lock out the delegates; as a result, the members of the Third Estate marched to a nearby Tennis Court, where they took the "Tennis Court Oath" declaring themselves the National Assembly. The King was forced within a matter of days to recognize the National Assembly's legitimacy due to the political situation's nature rapidly spiraling out of control, but that did not stop him from deploying more soldiers to the outskirts of Paris or from dismissing the popular Jacques Necker from office.

This sparked a panic in Paris; with Necker's dismissal and the rumored troop movements, the citizens of the French capital took action. Armed with muskets, pitchforks, shovels, swords, knives, cleavers, and whatever other implements of destruction they could muster, the crowds swelled in size as they marched on the Bastille. The ancient fortress and prison had long served as a symbol of the Ancien Regime's hold on power. Though the soldiers guarding the garrison initially resisted the assault, the realization that they would eventually be massacred led to them surrendering the fortress and releasing all of the prisoners within. The fall of the Bastille marked the defining turning point of the French Revolution.

The National Assembly declared themselves the true government of France in the aftermath of the fall of the Bastille, and set about writing a constitution that would effectively abolish feudalism and clericalism in France. The King, though retained in power, would see his influence and authority over the country significantly weakened under the new constitutional arrangement. The power of the nobility and church would likewise be restricted, with the mandatory tithe that sustained the Church's clergy being abolished. A document entitled the Declaration of the Right's of Man - influenced by the enlightenment and the autonomist movement in British America - would also be adopted. Yet the King, who never had any influence or interest in politics, nevertheless managed to offend with his indifference to the state of the peasantry. Though the feared interference with the National Assembly never came to pass, the rumors surrounding the monarchy continued to spark discontent. Women came to distrust the Queen Marie Antoinette in particular due to allegations that she was conspiring with her Austrian relatives to create a coalition of European powers willing to intervene against the revolution. Likewise, the decadence of the Royal couple did little more to endear them to the public. When rumor reached Paris that the King had led a crowd of the noble elites to trample the tricolor flag which had come to symbolize the revolution, all hell broke loose.

A mob of women, primarily the fishmongers of Paris, marched on Versailles. Armed with weapons confiscated from the Bastille, they numbered in the thousands as they made their way to the palace on the outskirts of the city. The King and Queen were given little advanced notice, and were still on the grounds of the palace when the mob arrived. In fact, the Queen only managed to flee her apartments within a matter of mere minutes before it was completely ransacked by the enraged mob. From below, the crowd demanded an appearance from the Royal Family, which was given a few hours later. The King and Queen agreed to return to Paris to take up residence in the Tuilleries Palace, in order to end the isolation of the King and upper-nobility, not knowing that it would be the final time they would leave their beloved Versailles.

All the while, events in France were being eyed with great suspicion in foreign capitals. In London, the King and his Prime Minister feared the revolution would embolden American insurrectionists to rise again. Likewise, in Vienna, the Holy Roman Emperor watched in horror as his sister became a virtual prisoner in her palace. In Paris, the political clubs began to form. Through the Jacobins, one of the most radical factions, a young lawyer named Maximilian Robespierre rose to become one of the leading and most rabid voice in favor of the new regime. The Royal Family by 1791 realized their position was unprecedentedly perilous; they attempted to flee Paris disguised as servants, but were ultimately caught near the border in Verdun. Subsequently, they were marched back to Paris, mocked as traitors, and subsequently imprisoned. They were the lucky ones; many other imprisoned allies of the Ancien Regime were slaughtered in their prison cells by a mob of revolutionaries when false rumors of an impending Austrian-British-Prussian invasion to restore the King to power proliferated through the capitol.

As the Bourbons awaited their fate in Paris, the worst of the carnage was yet to come.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Threadmarks

View all 26 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XVIII: The Franklin Ministry & the Colombian collapse. Chapter XIX: The Northwest War & the French Revolution's early stages. Chapter XX: First in the Hearts of his Countrymen. Chapter XXI: The 1790 Federal Election Chapter XXII: Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite Chapter XXIII: Westward Ho! Chapter XXIV: The Haitian Revolution Chapter XXV: The early Industrial Revolution in America.

Share: