You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

For God, Crown, and Country: The Commonwealth of America.

- Thread starter Nazi Space Spy

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 26 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XVIII: The Franklin Ministry & the Colombian collapse. Chapter XIX: The Northwest War & the French Revolution's early stages. Chapter XX: First in the Hearts of his Countrymen. Chapter XXI: The 1790 Federal Election Chapter XXII: Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite Chapter XXIII: Westward Ho! Chapter XXIV: The Haitian Revolution Chapter XXV: The early Industrial Revolution in America.Nazi Space Spy

Banned

Pensacola is the capital of West Florida as 2020, and I'd assume it'd be the same in colonial times when it was still a British colony. Good question though, I might flash forward and make a few "present day" (no spoilers, of course) infoboxes that shed light on what the Commonwealth of America will evolve into. I plan to take this through 2020.Is Mobile or Pensacola the capital of West Florida?

Chapter XII: No Taxation without Representation.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

The financial burdens caused by the Seven Years War and the following conflict with Pontiac led to the government of George Grenville to take greater interest in securing North America, which was reflected by the larger budget passed by Parliament in 1765. To pay for these mounting debts, the issue of taxation arose in the House of Commons. George Grenville, the newly minted Prime Minister, was wary of raising taxes on the people of Britain proper due to the unrest caused by the Cider Tax a year earlier. So enraged were the citizens of the British Isles that they rioted in London and burned Grenville’s predecessor in effigy. Furthermore, most of the debt incurred during the war was used to fund the defenses of the colonies during the North American theater of the conflict.

George Grenville, the latest Prime Minister.One of the most notable features of the British system of colonial government was the degree of autonomy they had enjoyed. This dated back to the late 17th century, when the citizens of Boston overthrew the colonial government of the Andros. Though London regulated colonial commerce through several competing bodies of government (primarily through the Board of Trade), the American people had never been directly taxed by London; instead, their own colonial legislatures raised the revenue needed to sustain a civil society. The first attempt at direct taxation of the colonies was the Molasses Act of 1733, which imposed a duty of six pence on every gallon of molasses produced. The colonies simply did not enforce this tax, however, and the tax did not bring in enough revenue it its own right to cover the enforcement efforts. As a result, it remained an afterthought from bygone times. Three decades later, however, conditions had radically changed. The whole of the continent now belonged to the empire of King Frederick, which brought exuberant expenses with it.

The Sugar Act of 1764 was passed; despite its name, it was actually a series of taxes and tariffs. It required lumber from the colonies be sent to England only, and put a tariff of 90% on imported sugar, which effectively doubled the cost and threatened to put the entire rum industry out of business. The acts also required merchant ships to keep detailed logs about their cargo, and were required to be inspected by authorities before their goods could be unloaded. The leaders of the resistance to the Sugar Act were John Adams and Samuel Otis, both highly regarded and educated civic leaders in Boston. Their protests led to the citizens of Boston boycotting imports from Britain in response, which led to American manufacturing nearly doubling their output without the competition from the more firmly established industries based in Britain. While there was clear discontent brewing in the colonies, particularly in Boston, the British government in London were unconcerned for the moment. The triumph of the English over the French sustained a sense of arrogance in Westminster, which made them oblivious and worse yet, entirely uninterested in the colonial complaints. Even Benjamin Franklin could not convince the Prime Minister to change his mind, and the increasingly politically uninterested King declined to intervene.

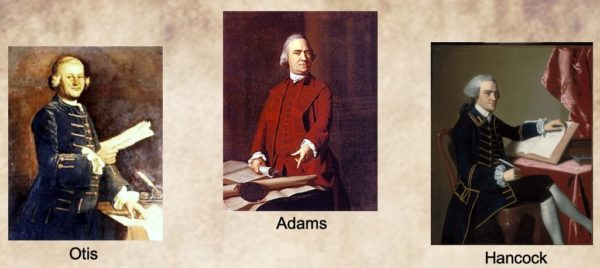

Samuel Otis, John Adams, and John Hancock were early critics of the new taxes.The Currency Act were particularly egregious to the colonists, who were opposed it with even more fervor than the Sugar Act. The law made the Sterling the only legal tender available in the colonies, which caused a severe capital shortage that brought the short burst of economic growth to a complete standstill. Also passed during this period was the Quartering Act, which was designed to address the housing shortage facing British soldiers spread across the colonies. This Act forced homeowners to take in British soldiers under penalty of law, which led to British troops being billeted in private residences. When the British government sent 1,500 Redcoats to New York, they were refused lodging and the provincial government, which was obligated to pay for the housing in lieu of London, claimed the currency acts prevented them from doing so. As a result, the soldiers were kept in crammed conditions on their ships in the harbor.

It was not quite shocking when Grenville announced the Stamp Act. The act would require all paper goods to be stamped, which came at a price. As a result, every sheet of paper also produced badly needed revenue for London; the cost of this legislation would be immense, with colonial leaders arguing that the tax was "extortion." The cry of "no taxation without representation" rang across New England down the eastern seaboard as the price of this decision was immense. The post-war patriotism of the colonies would quickly give way to dissent and cynicism. The major newspapers were flooded with anonymous letters which articulated the political atmosphere, often with the parliament and King being the center of their tersely worded broadsides.

The calls for resistance to the Stamp Act and the Quartering Act grew increasingly louder as time went by, and the King appointed revenue agents for each colony to collect the tax in anticipation of disobedience. At first, the resistance was initially peaceful, with protests and disapproving resolutions being passed by the individual legislatures in a few of the colonies. But their pleas went unheard, and the public increasingly employed mob violence against tax collectors up and down the coast while in Massachusetts, Governor Hutchison’s mansion was ransacked and virtually destroyed by a frenzied mob. Angered by the impact of the tax, “committees of correspondence” were formed in order to organize the resistance, followed by the creation of a shadowy group known as the “Sons of Liberty” which began attacking and even tarring and feathering tax collectors during this time.

A result of this was the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, which met in October in New York City. Delegates from the middle and northern colonies attended, where a resolution was passed condemning the tax was passed easily. This treatise outlined fourteen grievances and a defense of the colonial citizen’s natural rights. A copy was sent to the King and both chambers of Parliament, which went largely ignored. Though their own efforts and pleas fell on deaf ears, the political turmoil that afflicted England during time became a God-send to the colonists. Grenville’s government fell, to be replaced by the more enlightenment leaning Charles Watson-Wentworth, better known as the Marquis of Rockingham. Sympathetic to the colonial cry of “no taxation without representation,” Rockingham invited Benjamin Franklin to speak before the House of Commons, where he articulated the grievances of the leadership in the American colonies and encouraged MPs to revisit the proposed Albany Plan proposed a decade earlier. The result of Franklin’s well received address was the Declaratory Act, which reduced the Sugar Tax, but also codified the right of the crown and parliament in London to regulate the affairs of the Atlantic colonies. It was met with mixed reaction across the Atlantic, and Franklin himself attempted to voice his frustration to the King, who retained confidence in his government. The King however was not interested in politics, and after speaking to his cabinet about the act, continued to throw his weight behind Prime Minister Rockingham and later, William Pitt the Elder, the hero of the Seven Years War.

Chancellor Charles Townshend.William Pitt the Elder was, like his predecessor, inclined to the colonists and their grievances. However, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Charles Townsend, was less sympathetic and determined to balance the books. A series of laws proposed by him particularly enraged the colonists. The New York Restraint Act of 1767 was the first, which forbade the Governor and Assembly of New York from passing any laws until the colony complied with the Quartering Act. They didn’t budge, and parliament effectively suspended the colony’s government. The Revenue Act of 1767 placed taxes on glass, lead, painters' colors, and raised taxes on paper. Meanwhile, the West Indies colonies and the East India Company were the beneficiaries of a tax cut which Grenville argued would result in the price of tea going down due to the increased commerce. The Commissioner of Customs Act, also of 1767, created a regulatory body that would inspect imports in the major ports. Lastly, over a year later came the Admiralty Courts Act, which gave the British navy the right to prosecute smugglers, which was previously handled in civil courts before a jury. Pitt's tenure as Prime Minister was relatively brief despite his lengthy career and legacy, with his sympathies to the colonial cause putting him into conflict with Chancellor Townsend. This led to the internal disintegration of his cabinet, and he was forced to resign when it became clear that he couldn't command the confidence of the House of Commons.

While Townsend's efforts had some effect, they failed to fully curb the smuggling epidemic and many of these unpopular laws only had a marginal, if still noticeable example. In one famed incident, businessman and smuggler John Hancock locked a customs inspectors inside his ship’s cabin while his crew unloaded their cargo duty free. This was enough to see Hancock arrested, though charges were later dropped. Later, as a response to the Hancock incident, the British deployed a fifty cannon warship to Boston harbor. The use of British soldiers to regulate trade remained in place for four more years, in which tensions between the citizens of the New World – particularly in Boston – threatened to erupt into revolt. An uneasy peace continued during this time, and life was largely the same despite several economic upheavals caused by the British government’s imposition of taxes. But in 1774, with the Seven Years War now firmly in a past for over a decade, Britain could no longer sustain the practice of “taxation without representation.” They had simply run out of time. As a new Prime Minister, Lord North, succeeded Grafton (who had in turn succeeded Pitt the Elder after he was compelled to resign a year into his tenure due to health reasons. But there was one more tax needing to be imposed, and this time, it was simply too much.

Lord North, Prime Minister of Britain and a fierce supporter of taxation.

George Grenville, the latest Prime Minister.

The Sugar Act of 1764 was passed; despite its name, it was actually a series of taxes and tariffs. It required lumber from the colonies be sent to England only, and put a tariff of 90% on imported sugar, which effectively doubled the cost and threatened to put the entire rum industry out of business. The acts also required merchant ships to keep detailed logs about their cargo, and were required to be inspected by authorities before their goods could be unloaded. The leaders of the resistance to the Sugar Act were John Adams and Samuel Otis, both highly regarded and educated civic leaders in Boston. Their protests led to the citizens of Boston boycotting imports from Britain in response, which led to American manufacturing nearly doubling their output without the competition from the more firmly established industries based in Britain. While there was clear discontent brewing in the colonies, particularly in Boston, the British government in London were unconcerned for the moment. The triumph of the English over the French sustained a sense of arrogance in Westminster, which made them oblivious and worse yet, entirely uninterested in the colonial complaints. Even Benjamin Franklin could not convince the Prime Minister to change his mind, and the increasingly politically uninterested King declined to intervene.

Samuel Otis, John Adams, and John Hancock were early critics of the new taxes.

It was not quite shocking when Grenville announced the Stamp Act. The act would require all paper goods to be stamped, which came at a price. As a result, every sheet of paper also produced badly needed revenue for London; the cost of this legislation would be immense, with colonial leaders arguing that the tax was "extortion." The cry of "no taxation without representation" rang across New England down the eastern seaboard as the price of this decision was immense. The post-war patriotism of the colonies would quickly give way to dissent and cynicism. The major newspapers were flooded with anonymous letters which articulated the political atmosphere, often with the parliament and King being the center of their tersely worded broadsides.

The calls for resistance to the Stamp Act and the Quartering Act grew increasingly louder as time went by, and the King appointed revenue agents for each colony to collect the tax in anticipation of disobedience. At first, the resistance was initially peaceful, with protests and disapproving resolutions being passed by the individual legislatures in a few of the colonies. But their pleas went unheard, and the public increasingly employed mob violence against tax collectors up and down the coast while in Massachusetts, Governor Hutchison’s mansion was ransacked and virtually destroyed by a frenzied mob. Angered by the impact of the tax, “committees of correspondence” were formed in order to organize the resistance, followed by the creation of a shadowy group known as the “Sons of Liberty” which began attacking and even tarring and feathering tax collectors during this time.

A result of this was the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, which met in October in New York City. Delegates from the middle and northern colonies attended, where a resolution was passed condemning the tax was passed easily. This treatise outlined fourteen grievances and a defense of the colonial citizen’s natural rights. A copy was sent to the King and both chambers of Parliament, which went largely ignored. Though their own efforts and pleas fell on deaf ears, the political turmoil that afflicted England during time became a God-send to the colonists. Grenville’s government fell, to be replaced by the more enlightenment leaning Charles Watson-Wentworth, better known as the Marquis of Rockingham. Sympathetic to the colonial cry of “no taxation without representation,” Rockingham invited Benjamin Franklin to speak before the House of Commons, where he articulated the grievances of the leadership in the American colonies and encouraged MPs to revisit the proposed Albany Plan proposed a decade earlier. The result of Franklin’s well received address was the Declaratory Act, which reduced the Sugar Tax, but also codified the right of the crown and parliament in London to regulate the affairs of the Atlantic colonies. It was met with mixed reaction across the Atlantic, and Franklin himself attempted to voice his frustration to the King, who retained confidence in his government. The King however was not interested in politics, and after speaking to his cabinet about the act, continued to throw his weight behind Prime Minister Rockingham and later, William Pitt the Elder, the hero of the Seven Years War.

Chancellor Charles Townshend.

While Townsend's efforts had some effect, they failed to fully curb the smuggling epidemic and many of these unpopular laws only had a marginal, if still noticeable example. In one famed incident, businessman and smuggler John Hancock locked a customs inspectors inside his ship’s cabin while his crew unloaded their cargo duty free. This was enough to see Hancock arrested, though charges were later dropped. Later, as a response to the Hancock incident, the British deployed a fifty cannon warship to Boston harbor. The use of British soldiers to regulate trade remained in place for four more years, in which tensions between the citizens of the New World – particularly in Boston – threatened to erupt into revolt. An uneasy peace continued during this time, and life was largely the same despite several economic upheavals caused by the British government’s imposition of taxes. But in 1774, with the Seven Years War now firmly in a past for over a decade, Britain could no longer sustain the practice of “taxation without representation.” They had simply run out of time. As a new Prime Minister, Lord North, succeeded Grafton (who had in turn succeeded Pitt the Elder after he was compelled to resign a year into his tenure due to health reasons. But there was one more tax needing to be imposed, and this time, it was simply too much.

Lord North, Prime Minister of Britain and a fierce supporter of taxation.

Chapter XIII: The American Revolt & the Rockingham Ministry.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

The last straw that nearly threw the colonies into revolution was the Tea Act 1773, which gave the East India Company a monopoly over the sale of tea in the North American colonies. The East India Company, which was teetering of insolvency, lobbied for the monopoly over American trade in order to have a firm and steady line of income heavily in the years following the Seven Years War, which wreaked havoc on international trade. The tea monopoly failed to reduce prices and threatened the thriving industry of imported Dutch tea from their South American colonies, which was generally cheaper. But worst of all was the tax placed on the purchase of tea from the company disadvantaged the colonies but not the East India Company. The revenue generated by this hated tax was used to pay for the continued occupation and quartering of British soldiers. This infuriated the elites who comprised much of the colonial leadership, and the Sons of Liberty were particularly vocal as they protested these new taxes at a time when there was already enough bad blood between the colonies and the mother country; there had been a rising sense of cynicism and growing regional identity ever since the British troops used the Quartering Act to station themselves in the major Atlantic port cities like Boston, Charleston, Halifax, New York, and Philadelphia. By 1770, the established presence of redcoats in Boston was specifically contentious as they exercised their right to appropriate property to house themselves liberally, all of this made possible by the punitive stipulations of the Quartering Act.

The soldiers stationed in Boston soon found themselves in front of an angry mob who were tired of their continued presence in the city. Words and allegations were exchanged, and both sides hurled abuse at one another. Finally snowballs began to fly, and this soon evolved into frozen chunks of ice instead. When one of the soldiers stationed there was hit in the mouth by a lump of hard, frozen ice that left him bloodied and with a cracked tooth. Seeing this, the other soldiers present raised their muskets to the crowd in the hopes of scaring them off. That’s when the first shot rang out, causing the other Redcoats to open fire. Five people day laid dead in the street in the aftermath of the "Boston massacre," one of them being Crispus Attucks, a former slave who lived freely in city. Though it remains unclear who fired first, it was the judgement of a civil court that the soldiers present were guilty of manslaughter. The Boston Massacre was the most egregious assault on the colonists since the arrival of British troops. Anti-London sentiments spread as dissenters argued that they’ve become virtual prisoners in their own homeland following the end of the Seven Years War, with printing presses up and down the Atlantic seaboard publishing increasingly critical attacks on the government. The failing health of King Frederick weakened the colony's influence in London as his eldest son, Prince George of Wales, increasingly found himself aligned with the more conservative factions of the parliament. It became clear, at least to the citizens of Boston, that dramatic action would be required to make their voices heard.

This would be the impetus for the so called “Boston Tea Party.” A particularly rowdy gathering of the Sons of Liberty resulted in several citizens symbolically paint themselves like Mohawk Warriors (expressing their belief that they were Americans first, and subjects of King Frederick secondly) and stormed the East India ships docked in the harbor, dumping over barrel after barrel of tea into the harbor. The full extent of the financial damage was so severe that it’d today be valued as being worth millions of dollars, and the loss was so starkly in defiance of the government that Lord North ordered the closure of Boston’s port altogether.

The Boston Tea Party was an early act civil disobedience. This was the impetus of the Intolerable Acts, which were specifically designed to punish the rebellious colony of Massachusetts. The port of Boston was to remain closed until the East India Company was either compensated for or otherwise able to recoup the dumped tea, while another act stripped the colony of its charter and prohibited town hall meetings. A third law stripped the right of the accused to a trial by jury, with the entire judiciary of the colony being brought under the direct control of London. These were called the “Intolerable Acts” due to their draconian nature, and the passage of the new laws by parliament came at a time of great uncertainty. With few allies in parliament, the colony's greatest sympathizer, the King himself, had been almost entirely incapacitated by gout. He would die at Kensington Palace a month later following a final, fatal stroke. The new King, George III, was more politically involved than his father and predecessor, and likewise much more inclined to support the heavy handed policies of Lord North.

Other colonies were alarmed by the punishment that Massachusetts was handed, and protests in solidarity with the citizens of Boston broke out across the colonies in spite of concerns that such legislation could be enacted against them as well. Even in the rural areas, there was discontent with the crown as agricultural regions continued to slowly become increasingly crowded as more and more immigrants arrived from Europe. The Proclamation of 1763 which had prohibited settlement over the Appalachians, also became one of the numerous grievances the people of the colonies had. Indeed, many by this point saw themselves as “American” more than they did “British” despite the mother country’s continued sovereignty over them.

In 1774, the first Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia. Delegates representing every colony from Georgia to New Hampshire assembled to assess their grievances and address the Crown. Two factions quickly emerged; the conservatives, led by Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania, who favored pressuring the government in London to rescind the unpopular taxes and the much despised “Intolerable Acts” verses the radicals, the likes of Patrick Henry and to a lesser extent, John Adams, who called for the adoption of a colonial bill of rights. To the likes of John Adams, the conservative faction was no different from the hated Governor Hutchison of Massachusetts, who ironically was an influential attendee at the original Albany Convention. Yet the radicals offered up an unprecedented and uncharted course, one which would no doubt accompanied by further deadly strife.

Sensing the growing chasm between the colonists and the mother-country, Galloway resolved to create a compromise that could substantiate a lasting peace. For inspiration, he turned to the proposal of his fellow Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin from twenty years prior. The Albany Plan, a failed attempt by Franklin to unite the colonies under one government, offered what Galloway believed to be the perfect compromise: the preservation of both the authority of the crown and the autonomy of the colonies. The post-war crises and growing revolutionary idealism represented a serious threat to both, and Galloway and his allies worked hard to isolate the most radical voices. First, Galloway joined calls for the extension of invitations to the Canadian colonies and encouraged more skeptical conservative delegates to support a second Continental Congress for the following May. These actions gained the trust of the more moderate patriots and radicals among the delegates, while also ensuring the skeptical authorities in Quebec and Halifax saw the convention as more than a gaggle of anti-tax troublemakers. The move solidified his position as one of the clear leaders of the convention, which adjourned after passing a resolution calling for a boycott of British imports.

When the Second Continental Congress assembled the following May, Galloway was returned as a member of the Pennsylvania delegation. The stakes were higher; open rebellion had broken out at Lexington and Concord, where British attempts to seize militia stores were successfully resisted. Now the patriot militias besieged Boston, where General William Howe and Thomas Gage nervously awaited instruction from London. Though rebellious spirits ran high, this time Galloway and the conservatives had the numbers on their side. The addition of Canadian delegates to the convention served as a counterweight to the radicals, and they successfully tabled a measure to assemble the rebellious militias together as a continental army as a result. This decision gave the British the confidence in knowing that an attack on these rebel forces would preclude widespread revolution, and as a result, the redcoats soon overran the rebel positions after the Battle of Bunker Hill, resulting in the armed rebellion dissipating. The conservatives at the convention saw an opportunity, and offered up the “Olive Branch Petition” as a result. The despairing radicals, fearing punishment for their support of the crushed rebellion, signed onto the petition as well. Drafted by Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and others, the petition requested the British parliament authorize the Continental Congress as the legislative body governing the American colonies. The demands for autonomy were met with skepticism in London when the Olive Branch Petition arrived in the personal care of Benjamin Franklin himself, but the political climate in London was beneficial to the Continental Congress in the long run.

The battle of Bunker Hill - the start and end of the American Revolt.In the aftermath of the short-lived American crisis, Lord North’s government had been thrown into chaos. The London press attacked the Prime Minister regularly, with editorials appearing often alongside the anonymous letters of MPs in printed broadsides. This campaign was so successful in undermining the public’s confidence in North’s ability to contain the rebellion in the colonies that it ultimately resulted in his dismissal from the office by King George III. To replace North, William Pitt the Elder, the elderly statesman and hero of the Seven Years War, was selected. Though he was at that time 66 years old, then a relatively advanced age, Pitt secured the support of Rockingham’s Whigs and formed a government. When news reached Philadelphia of the North government’s fall, the Continental Congress voted to appoint Benjamin Franklin as their permanent representative in London. Newly empowered by his colleagues, Pitt invited Franklin to personally negotiate an agreement that could bring about a lasting peace. The process took nearly three months, extending into August of 1775. But in the end, Franklin was able to secure the repeal of the “Intolerable Acts,” amnesty for all who took up arms against the crown in Boston, and an agreement to lower the taxes imposed on the colonies as well as a guarantee that the Continental Congress could continue to convene freely. Franklin returned to the colonies a hero, feted in Philadelphia upon his arrival as the “first citizen” of the New World (as he was hailed in the papers).

The Continental Congress would meet again in 1777 and 1779, each time passing resolutions calling for increased autonomy and greater cooperation between the colonial legislatures and calling for increased autonomy. The Galloway Plan remained a popular proposal, with the legislative bodies of the American colonies regularly passing resolutions favoring the adoption of the plan. Yet little progress was made. Slowly, life returned to the normalcy that the colonies had not enjoyed since the onset of the Seven Years War. Trade with Britain resumed after the 1777 Continental Congress formally ended the boycotts of British imports, and the lowered taxes resulted in both a steady (albeit reduced) stream of revenue for London and greater economic expansion in the colonies.

The 1778 death of the Earl of Chatham and his succession by the Earl of Rockingham ensured that the colonies continued to have a sympathetic ear in London. Rockingham’s ministry would last four years until 1782, and the Earl of Shelbourne and the Duke of Portland both formed similar governments that desired to maintain the status quo in the years afterwards. The impact of the changing political consensus since the premature political demise of Lord North meant that the Tories, who had traditionally favored a more heavy handed approach to North America, also adapted to the changing times. Following the fall of the Duke of Portland’s government, which had alienated the conservative King George III due to the influence of radical Charles James Fox, the Tories were returned to power under William Pitt the Younger. An admirer of the Americans like his father, news of Pitt’s ascension to the Empire’s most influential office in 1783 resulted in increased talk in the colonies of pushing for another Continental Congress.

Since the last Continental Congress in 1779, a number of new issues faced the colonies as the 1780s became underway. Trade disputes and conflicting regional interests resulted in the colonies competing with each other before such institutions such as the Board of Trade, which would often favorite individual colonies in order to advance the interests of the government in London. The warnings from radicals such as Patrick Henry and his fellow Virginia legislator Thomas Jefferson that the current situation was resulting in the silent undermining of the colony’s autonomy caught wind in the press, and soon the former opponents of the Galloway plan became its most ardent proponents as a means of preventing further draconian impositions being placed on the American colonies.

Pitt the elder's intervention and leadership had quelled the crisis, and in doing so also opened a more serious dialogue about reforming the colonial leadership. The King himself, albeit considerably more conservative than his reform minded father, had nevertheless learned from Pitt and his late father, King Frederick, during their successful efforts to quell the American troubles. In fact, the monarch had taken up an admiration of the Americas for their autonomous spirit and willing loyalty, and was captivated by the largely agrarian society that flourished across the Atlantic. Though he possessed a deep sense of distrust of the radicals, such as Mr. Fox, he found himself in agreement with the sentiments of the more conservative Edmund Burke; it was the King himself who proposed the idea of an American Magna Carta to the Prime Minister, and afterwards many of Pitt the younger's Ministers began envisioning such an idea.

Word would soon hit the London press, and a few weeks later, slowly began to proliferate itself within in the pages of the American press as well. The cries of “No Taxation without Representation” were revived, and many leading figures of the colonial elite began to voice support for a number of proposals that would give the colonies a voice in Parliament. Ben Franklin, the most prominent citizen perhaps in all of the Americas, had used his voice and paper to publish support for a plan in which each colony would be granted a single resident commissioner to be elected by the state legislature. This officer would act as both an MP in the House of Commons as well as an Ambassador of sorts handling his respective colony’s interests in London.

The result of this momentum was the 1780 adoption of the British America Act, which in effect served as an American magna carta. The document guaranteed each colony the right to a legislative assembly and a considerably greater degree of autonomy, as well as allowing a Resident Commissioner from each province a seat, voice, and vote in Parliament. Most critically, Rockingham appointed his longtime private secretary and fellow MP Edmund Burke as the first Secretary of State for the American Department. A philosopher and scholar, Burke was a well-respected defender of enlightenment values and was a firm sympathizer with the colonial patriots, which made him the de-facto go between the new and old worlds. In the final two years of the Rockingham ministry, Burke successfully shepherded several bills through Parliament. The first of which, the American Commerce Act, created an independent American Board of Trade subordinate to the American Department that none the less relaxed British control of colonial ports, aside from defensive and military related installations. The board was empowered by this act to levy and collect taxes from the colonies and would likewise be authorized to negotiate on behalf of them in areas concerning finance, commerce, and taxation.

The Marquess of Rockinghan, Pitt the Elder's successor.The policies pursued by the Board during this time would fuel an economic boom that would result in a new wave of immigration and large scale economic growth and development. The East India Company, though allowed to maintain their monopolies, were soon bound by order of the board to invest considerable sums of money into colonial port cities in order to alleviate financial burdens to the colonies. In 1784, twenty years after the initial proclamation was issued, the prohibition of settlement beyond the Appalachians was lifted after the intense lobbying done by the American colony’s resident commissioners as available land rapidly disappeared. It was an early political success for the newly enfranchised American resident-commissioners and would have wide ranging effects on the New World. But in the Old World, trouble was brewing as a young French General with ubridled ambition prepared to leave his mark on the world.

The soldiers stationed in Boston soon found themselves in front of an angry mob who were tired of their continued presence in the city. Words and allegations were exchanged, and both sides hurled abuse at one another. Finally snowballs began to fly, and this soon evolved into frozen chunks of ice instead. When one of the soldiers stationed there was hit in the mouth by a lump of hard, frozen ice that left him bloodied and with a cracked tooth. Seeing this, the other soldiers present raised their muskets to the crowd in the hopes of scaring them off. That’s when the first shot rang out, causing the other Redcoats to open fire. Five people day laid dead in the street in the aftermath of the "Boston massacre," one of them being Crispus Attucks, a former slave who lived freely in city. Though it remains unclear who fired first, it was the judgement of a civil court that the soldiers present were guilty of manslaughter. The Boston Massacre was the most egregious assault on the colonists since the arrival of British troops. Anti-London sentiments spread as dissenters argued that they’ve become virtual prisoners in their own homeland following the end of the Seven Years War, with printing presses up and down the Atlantic seaboard publishing increasingly critical attacks on the government. The failing health of King Frederick weakened the colony's influence in London as his eldest son, Prince George of Wales, increasingly found himself aligned with the more conservative factions of the parliament. It became clear, at least to the citizens of Boston, that dramatic action would be required to make their voices heard.

This would be the impetus for the so called “Boston Tea Party.” A particularly rowdy gathering of the Sons of Liberty resulted in several citizens symbolically paint themselves like Mohawk Warriors (expressing their belief that they were Americans first, and subjects of King Frederick secondly) and stormed the East India ships docked in the harbor, dumping over barrel after barrel of tea into the harbor. The full extent of the financial damage was so severe that it’d today be valued as being worth millions of dollars, and the loss was so starkly in defiance of the government that Lord North ordered the closure of Boston’s port altogether.

The Boston Tea Party was an early act civil disobedience.

Other colonies were alarmed by the punishment that Massachusetts was handed, and protests in solidarity with the citizens of Boston broke out across the colonies in spite of concerns that such legislation could be enacted against them as well. Even in the rural areas, there was discontent with the crown as agricultural regions continued to slowly become increasingly crowded as more and more immigrants arrived from Europe. The Proclamation of 1763 which had prohibited settlement over the Appalachians, also became one of the numerous grievances the people of the colonies had. Indeed, many by this point saw themselves as “American” more than they did “British” despite the mother country’s continued sovereignty over them.

In 1774, the first Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia. Delegates representing every colony from Georgia to New Hampshire assembled to assess their grievances and address the Crown. Two factions quickly emerged; the conservatives, led by Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania, who favored pressuring the government in London to rescind the unpopular taxes and the much despised “Intolerable Acts” verses the radicals, the likes of Patrick Henry and to a lesser extent, John Adams, who called for the adoption of a colonial bill of rights. To the likes of John Adams, the conservative faction was no different from the hated Governor Hutchison of Massachusetts, who ironically was an influential attendee at the original Albany Convention. Yet the radicals offered up an unprecedented and uncharted course, one which would no doubt accompanied by further deadly strife.

Sensing the growing chasm between the colonists and the mother-country, Galloway resolved to create a compromise that could substantiate a lasting peace. For inspiration, he turned to the proposal of his fellow Pennsylvanian Benjamin Franklin from twenty years prior. The Albany Plan, a failed attempt by Franklin to unite the colonies under one government, offered what Galloway believed to be the perfect compromise: the preservation of both the authority of the crown and the autonomy of the colonies. The post-war crises and growing revolutionary idealism represented a serious threat to both, and Galloway and his allies worked hard to isolate the most radical voices. First, Galloway joined calls for the extension of invitations to the Canadian colonies and encouraged more skeptical conservative delegates to support a second Continental Congress for the following May. These actions gained the trust of the more moderate patriots and radicals among the delegates, while also ensuring the skeptical authorities in Quebec and Halifax saw the convention as more than a gaggle of anti-tax troublemakers. The move solidified his position as one of the clear leaders of the convention, which adjourned after passing a resolution calling for a boycott of British imports.

When the Second Continental Congress assembled the following May, Galloway was returned as a member of the Pennsylvania delegation. The stakes were higher; open rebellion had broken out at Lexington and Concord, where British attempts to seize militia stores were successfully resisted. Now the patriot militias besieged Boston, where General William Howe and Thomas Gage nervously awaited instruction from London. Though rebellious spirits ran high, this time Galloway and the conservatives had the numbers on their side. The addition of Canadian delegates to the convention served as a counterweight to the radicals, and they successfully tabled a measure to assemble the rebellious militias together as a continental army as a result. This decision gave the British the confidence in knowing that an attack on these rebel forces would preclude widespread revolution, and as a result, the redcoats soon overran the rebel positions after the Battle of Bunker Hill, resulting in the armed rebellion dissipating. The conservatives at the convention saw an opportunity, and offered up the “Olive Branch Petition” as a result. The despairing radicals, fearing punishment for their support of the crushed rebellion, signed onto the petition as well. Drafted by Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and others, the petition requested the British parliament authorize the Continental Congress as the legislative body governing the American colonies. The demands for autonomy were met with skepticism in London when the Olive Branch Petition arrived in the personal care of Benjamin Franklin himself, but the political climate in London was beneficial to the Continental Congress in the long run.

The battle of Bunker Hill - the start and end of the American Revolt.

The Continental Congress would meet again in 1777 and 1779, each time passing resolutions calling for increased autonomy and greater cooperation between the colonial legislatures and calling for increased autonomy. The Galloway Plan remained a popular proposal, with the legislative bodies of the American colonies regularly passing resolutions favoring the adoption of the plan. Yet little progress was made. Slowly, life returned to the normalcy that the colonies had not enjoyed since the onset of the Seven Years War. Trade with Britain resumed after the 1777 Continental Congress formally ended the boycotts of British imports, and the lowered taxes resulted in both a steady (albeit reduced) stream of revenue for London and greater economic expansion in the colonies.

The 1778 death of the Earl of Chatham and his succession by the Earl of Rockingham ensured that the colonies continued to have a sympathetic ear in London. Rockingham’s ministry would last four years until 1782, and the Earl of Shelbourne and the Duke of Portland both formed similar governments that desired to maintain the status quo in the years afterwards. The impact of the changing political consensus since the premature political demise of Lord North meant that the Tories, who had traditionally favored a more heavy handed approach to North America, also adapted to the changing times. Following the fall of the Duke of Portland’s government, which had alienated the conservative King George III due to the influence of radical Charles James Fox, the Tories were returned to power under William Pitt the Younger. An admirer of the Americans like his father, news of Pitt’s ascension to the Empire’s most influential office in 1783 resulted in increased talk in the colonies of pushing for another Continental Congress.

Since the last Continental Congress in 1779, a number of new issues faced the colonies as the 1780s became underway. Trade disputes and conflicting regional interests resulted in the colonies competing with each other before such institutions such as the Board of Trade, which would often favorite individual colonies in order to advance the interests of the government in London. The warnings from radicals such as Patrick Henry and his fellow Virginia legislator Thomas Jefferson that the current situation was resulting in the silent undermining of the colony’s autonomy caught wind in the press, and soon the former opponents of the Galloway plan became its most ardent proponents as a means of preventing further draconian impositions being placed on the American colonies.

Pitt the elder's intervention and leadership had quelled the crisis, and in doing so also opened a more serious dialogue about reforming the colonial leadership. The King himself, albeit considerably more conservative than his reform minded father, had nevertheless learned from Pitt and his late father, King Frederick, during their successful efforts to quell the American troubles. In fact, the monarch had taken up an admiration of the Americas for their autonomous spirit and willing loyalty, and was captivated by the largely agrarian society that flourished across the Atlantic. Though he possessed a deep sense of distrust of the radicals, such as Mr. Fox, he found himself in agreement with the sentiments of the more conservative Edmund Burke; it was the King himself who proposed the idea of an American Magna Carta to the Prime Minister, and afterwards many of Pitt the younger's Ministers began envisioning such an idea.

Word would soon hit the London press, and a few weeks later, slowly began to proliferate itself within in the pages of the American press as well. The cries of “No Taxation without Representation” were revived, and many leading figures of the colonial elite began to voice support for a number of proposals that would give the colonies a voice in Parliament. Ben Franklin, the most prominent citizen perhaps in all of the Americas, had used his voice and paper to publish support for a plan in which each colony would be granted a single resident commissioner to be elected by the state legislature. This officer would act as both an MP in the House of Commons as well as an Ambassador of sorts handling his respective colony’s interests in London.

The result of this momentum was the 1780 adoption of the British America Act, which in effect served as an American magna carta. The document guaranteed each colony the right to a legislative assembly and a considerably greater degree of autonomy, as well as allowing a Resident Commissioner from each province a seat, voice, and vote in Parliament. Most critically, Rockingham appointed his longtime private secretary and fellow MP Edmund Burke as the first Secretary of State for the American Department. A philosopher and scholar, Burke was a well-respected defender of enlightenment values and was a firm sympathizer with the colonial patriots, which made him the de-facto go between the new and old worlds. In the final two years of the Rockingham ministry, Burke successfully shepherded several bills through Parliament. The first of which, the American Commerce Act, created an independent American Board of Trade subordinate to the American Department that none the less relaxed British control of colonial ports, aside from defensive and military related installations. The board was empowered by this act to levy and collect taxes from the colonies and would likewise be authorized to negotiate on behalf of them in areas concerning finance, commerce, and taxation.

The Marquess of Rockinghan, Pitt the Elder's successor.

oh no its Lafayette!

nah just kidding we all know who it is.

Yes, that dratted Bernadotte.

Chapter XIV: Confederation.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

1784 Constitutional Convention

Patrick Henry, the old radical, originally intended to boycott the convention, writing to his friend and fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson that he “smelt a rat” in Philadelphia. Yet, a week after the Congress opened in Philadelphia, he was convinced to travel to the city and take his place as a delegate after receiving word via letter of the strength of the “Galloway faction.” There was no room for compromise in Henry’s view with the likes of Galloway and Hamilton, who threatened the fragile autonomy of the individual provinces. More pragmatic than Patrick Henry was Thomas Jefferson, who likewise favored a looser confederation but was less outwardly sympathetic to the republican cause. A scientist and farmer of some repute, the shy and introverted Jefferson represented the younger generation of educated enlightenment era radicals. Committed to the cause of preserving individual liberty in the colonies, Jefferson – along with his friend and protégé James Madison – represented the more flexible side of the patriot wing of the Constitutional Convention.

Adams and Jefferson, two of the leading figures in the drafting process.

The first proposal by Alexander Hamilton was shot down almost from the beginning. His plan called for the amalgamation of the colonies into a single entity, though this idea was widely unpopular. Even the more reactionary loyalists, those of the Galloway faction, considered the idea of abolishing the colonies to be imprudent and radical. However, Hamilton’s ideas for the composition of an American parliament did indeed catch fire. Specifically, his proposal for a two chambered system, consisting of a lower House that would run the government and an upper-house that would work as a counter-weight to the Commons. Hamilton forged an unlikely alliance with James Madison, who pushed the “Virginia Plan” in which the legislative branch would have its membership apportioned by population. This plan was vigorously opposed by delegates from colonies like Delaware, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Rhode Island, who demanded a legislature in which each colony received equal representation in the parliament.

The “Franklin compromise” came about as a result of the dispute. The plan originated in Benjamin Franklin’s “Albany Plan,” and offered the convention a template for which to design the government. According to the proposal, the legislative branch would be bicameral, with a House of Commons apportioned by population and a Senate in which all colonies would be represented equally by life-serving Senators (the House, meanwhile, would be subject to an election at least every five years). The government would be drawn from members of both chambers, and would serve a Governor-General appointed by the King. To avoid further tyranny from London, Franklin added a provision that would allow the Senate to recall an unpopular Governor-General or Crown Appointee, albeit with numerous restrictions and caveats. The “Franklin Compromise” garnered more than enough support to be a credible proposal, but it was not without its critics. Radical republicans like Patrick Henry bulked at the prospect of retaining the monarchy, while Thomas Jefferson expressed concerns that the plan did little to remove the influence of London from American politics. However, Galloway expressed support for the plan, as did Hamilton after some convincing. Another skeptic, James Madison, was convinced to back the plan when Franklin offered him the opportunity to draft a formal Bill of Rights.

Joseph Galloway, an early Tory leader.

And so, on April 1st, 1785, after several long months of intense debate along with a long drafting process, the Constitution of the Commonwealth of America was ratified. It was then sent to the colonies, where it was approved by each legislature over the course of year. All the while, in London, the government of William Pitt the Younger attempted to rally support for the British North America Act of 1785 to approve of the document. The legislatures by and large were able to ratify the Constitution with relative ease, though colonial legislatures in North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Vermont were hesitant at first to embrace it. At last, on July 4th, 1785, the British North America Act of 1785 was ratified. The Commonwealth of America came into existence immediately upon obtaining royal assent with the Duke of York and Albany taking on the role of Governor General of the Commonwealth of America the following month. Almost immediately upon arrival in the Commonwealth, the Governor-General called a federal election and set America on the path towards establishing its first government.

Chapter XV: The Constitution of the Commonwealth of America.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

In the name of God, Crown, and Country, We The People of the Commonwealth of America, in order to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do hereby ordain and establish this Constitution for the Commonwealth of America.

Article I

Section I: All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Parliament of the Commonwealth of America, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Commons.

Article II

Section I: The House of Commons shall be composed of Members chosen every fifth year or whensoever the government cannot command the confidence of the House, by the people of the provinces of the Commonwealth, and the electors in each province shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the provincial legislature.

No person shall be a Member of the Commons who shall not have attained to the age of twenty five years, and been seven years a citizen of the Commonwealth, and who shall not, when elected, be an inhabitant of that province in which he shall be chosen.

Representatives to the Commons and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several provinces which may be included within this Commonwealth, according to their respective numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other persons. The actual enumeration shall be made within three years after the first meeting of the Parliament of the Commonwealth of America, and within every subsequent term of ten years, in such manner as they shall by law direct. The number of Members of the Commons shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand, but each province shall have at Least one Representative to the House; and until such enumeration shall be made, the province of Nova Scotia shall be entitled to choose two, Ontario two, New Hampshire three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Quebec one, Connecticut five, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland six, Virginia ten, North Carolina five, South Carolina five, Vermont one, and Georgia three.

When vacancies happen in the representation from any province, the Executive authority acting on behalf of the Crown thereof shall issue Writs of Election to fill such vacancies within no less than ninety days of the vacancy.

The House of Commons shall choose their Speaker and other Officers; and the confidence of this institution shall be necessary to govern the Commonwealth on behalf of the Crown and the Governor-General.

Section II: The Senate of the Commonwealth shall be composed of two Senators from each province, chosen by the Legislature thereof, for a life tenure; and each Senator shall have one vote.

Shall vacancies happen by resignation, or otherwise, during the recess of the legislature of any province, the executive thereof may make temporary appointments until the next meeting of the legislature, which shall then fill such vacancies.

No Person shall be a Senator who shall not have attained to the age of thirty years, and been nine years a citizen of the Commonwealth, and who shall not, when elected, be an inhabitant of that state for which he shall be chosen.

The Senate shall choose their other officers, and also a Principal of the Senate, who shall during the absence of a Governor-General shall act as the temporary executive authority of the crown until such an appointment can be made.

The Senate shall have the sole Power to try all impeachments of Crown appointed officers and magistrates. When sitting for that purpose, they shall be on oath or affirmation. When the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of America is tried, the Chief Justice shall preside: And no person shall be convicted without the concurrence of two thirds of the members present.

Judgment in cases of impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any office of honor, trust or profit under the Crown or Commonwealth: but the party convicted shall nevertheless be liable and subject to indictment, trial, judgment and punishment, according to law.

Section IV: The times, places and manner of holding elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each province by the legislature thereof; but the Parliament may at any time by law make or alter such regulations, except as to the places of choosing Senators.

The Parliament shall assemble at least once in every year, and such meeting shall be on the first Monday in December, unless they shall by law appoint a different day.

Section V: Each House shall be the judge of the elections, returns and qualifications of its own members, and a majority of each shall constitute a quorum to do business; but a smaller number may adjourn from day to day, and may be authorized to compel the attendance of absent members, in such manner, and under such penalties as each House may provide.

Each House may determine the rules of its proceedings, punish its members for disorderly behavior, and, with the concurrence of two thirds, expel a member.

Each House shall keep a journal of its proceedings, and from time to time publish the same, excepting such parts as may in their judgment require secrecy; and the Yeas and Nays of the members of either House on any question shall, at the desire of one fifth of those present, be entered on the journal.

Neither House, during the session of Parliament, shall, without the consent of the other, adjourn for more than three days, nor to any other place than that in which the two Houses be sitting.

Section VI: The Senators and Members of the House shall receive a compensation for their services, to be ascertained by law, and paid out of the Treasury of the Commonwealth. They shall in all cases, except treason, felony and breach of the peace, be privileged from arrest during their attendance at the session of their respective Houses, and in going to and returning from the same; and for any speech or debate in either House, they shall not be questioned in any other place.

No Senator or Member of the House shall, during the time for which he was elected, be appointed to any civil Office under the authority of the Commonwealth, which shall have been created, or the emoluments whereof shall have been increased during such time; and no person holding any office under the Commonwealth, shall be a Member of either House during his continuance in office.

Section VII: All bills for raising revenue shall originate in the House of Commons; but the Senate may propose or concur with amendments as on other bills.

Every bill which shall have passed the House of Commons and the Senate, shall, before it become a law, be presented to the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of America for assent on behalf of the crown: if approved by His Majesty, he shall sign it, but if not he shall return it, with his objections to that House in which it shall have originated. If any bill shall not be returned by the Governor-General within ten days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the same shall be a law, in like manner as if he had signed it, unless the Parliament by their adjournment prevent its return, in which case it shall not be a law.

Every order, resolution, or vote to which the concurrence of the Senate and House of Commons may be necessary (except on a question of adjournment) shall be presented to the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of America; and before the same shall take effect, shall be approved by him.

Section VIII: The Parliament shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the Commonwealth; but all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the Commonwealth;

To borrow money on the credit of the Commonwealth;

To regulate Commerce with foreign nations, and among the several provinces, and with the various Indian Tribes;

To establish an uniform rule of naturalization, and uniform laws on the subject of bankruptcies throughout the Commonwealth;

To coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin, and fix the standard of weights and measures;

To provide for the punishment of counterfeiting the securities and current coin of the Commonwealth;

To establish Post Offices and post roads;

To promote the progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries;

To constitute Tribunals inferior to the Supreme Court;

To define and punish piracies and felonies committed on the high seas, and offences against the Law of Nations;

To declare war, grant letters of marque and reprisal, and make rules concerning captures on land and water;

To raise and support armies, but no appropriation of money to that use shall be for a longer term than two years;

To provide and maintain a Navy;

To make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces;

To provide for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Commonwealth, suppress insurrections and repel invasions;

To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the militia, and for governing such part of them as may be employed in the service of the Commonwealth, reserving to the provinces respectively, the appointment of the officers, and the authority of training the militia according to the discipline prescribed by Parliament;

To exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such district (not exceeding ten miles square) as may, by cession of particular provinces, and the acceptance of Parliament, become the seat of the government of the Commonwealth, and to exercise like authority over all places purchased by the consent of the legislature of the state in which the same shall be, for the erection of forts, magazines, arsenals, dockyards and other needful buildings;—And

To make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution the foregoing powers and all other powers vested by this Constitution in the government of the Commonwealth, or in any Ministry or Officer thereof.

Section IX: The migration or importation of such persons as any of the states now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Parliament for a period of no less than twenty years after the assembling of the first Parliament, but a tax or duty may be imposed on such importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each person.

The privilege of the writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.

No bill of attainder or ex post facto law shall be passed.

No capitation, or other direct, tax shall be laid, unless in proportion to the census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken.

No tax or duty shall be laid on articles exported from any state.

No Preference shall be given by any regulation of commerce or revenue to the ports of one province over those of another: nor shall vessels bound to, or from, one province, be obliged to enter, clear or pay duties in another.

No money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in consequence of appropriations made by law; and a regular statement and account of the receipts and expenditures of all public money shall be published from time to time.

No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the civil government of the Commonwealth: And no person holding any office of profit or trust under them, shall, without the consent of the Parliament, accept of any present, emolument, office, or title, of any kind whatever, from any King or Prince or foreign State.

Section X: No province shall enter into any treaty, alliance, or confederation; grant letters of marque and reprisal; coin money; emit bills of credit; make anything but gold and silver, coin tender in payment of debts; pass any bill of attainder, ex post facto law, or law impairing the obligation of contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.

No province shall, without the consent of the Parliament, lay any imposts or duties on imports or exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it's inspection laws: and the net produce of all duties and imposts, laid by any province on imports or exports, shall be for the use of the Treasury of the Commonwealth; and all such laws shall be subject to the revision and control of the Parliament.

No province shall, without the consent of Parliament, lay any duty of tonnage, keep troops, or ships of war in time of peace, enter into any agreement or compact with another province, or with a foreign power, or engage in war, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent danger as will not admit of delay.

Article II

Section I: The executive power shall be vested in the Crown, held by His Majesty King George and his descendants, who shall reign under the title “King of the Commonwealth of America” and who shall exercise his authority through a Governor-General who serves at the pleasure of His Majesty.

Section II: His Majesty and his Governor-General shall be the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the Commonwealth, and of the militia of the several provinces when called into the actual service of the Commonwealth; he may require the opinion, in writing, of the principal officers in each of the Ministries, upon any subject relating to the duties of their respective offices, and he shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offences against the Commonwealth.

His Majesty and his Governor-General shall have power, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, to make treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur; and he shall nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the Commonwealth, whose appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by law: but the Parliament by law vest the appointment of such inferior officers, as they think proper, in His Majesty and the Governor-General alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of departments and Ministries.

His Majesty and his Governor General shall have power to fill up all vacancies to Crown Offices that may happen during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which shall expire at the end of their next session.

Section III: His Majesty, or his Governor-General, shall appoint a council of Ministers empowered to administrate the government and execute the policies enacted by Parliament as proscribed by law. The Prime Minister to the Governor-General shall be required to demonstrate he holds command of the confidence of Parliament.

Section IV: The Governor-General shall from time to time give to the Parliament information of the state of the Commonwealth, and recommend to their consideration such measures as his Ministers shall judge necessary and expedient; he may, on extraordinary occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in case of disagreement between them, with respect to the time of adjournment, he may adjourn them to such time as he shall think proper; he shall receive Ambassadors and other public Ministers; he shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed, and shall commission all the officers of the Commonwealth.

Section V: The Governor-General shall appoint, on the advice of the First Ministers of the provinces of the Commonwealth, a Lieutenant Governor to serve in his place as the executor of the authority of the Crown in the said province.

Article III

Section I: The judicial power of the Commonwealth shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Parliament may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the Supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behavior, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services, a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office.

Section II: The judicial power shall extend to all cases, in law and equity, arising under this constitution, the laws of the Commonwealth, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority;—to all cases affecting Ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls;—to all cases of admiralty and maritime jurisdiction;—to controversies to which the Commonwealth shall be a party;—to controversies between two or more provinces;—between a province and citizens of another province;—between citizens of different provinces;—between citizens of the same province claiming lands under grants of different provinces, and between a province, or the citizens thereof, and foreign states, citizens or subjects.

In all cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a province shall be party, the Supreme Court shall have original jurisdiction. In all the other cases before mentioned, the Supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction, both as to law and fact, with such exceptions, and under such regulations as the Parliament shall make.

The trial of all crimes, except in cases of impeachment, shall be by jury; and such trial shall be held in the province where the said crimes shall have been committed; but when not committed within any province, the trial shall be at such place or places as the Parliament may by law have directed.

Section III: Treason against the Commonwealth, shall consist only in levying war against the Crown or it’s citizens, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open court.

The Parliament shall have power to declare the punishment of treason, but no attainder of treason shall work corruption of blood, or forfeiture except during the life of the person attainted.

Article IV

Section I: Full faith and credit shall be given in each province to the public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of every other province. And the Parliament may by general laws prescribe the manner in which such acts, records and proceedings shall be proved, and the effect thereof.

Section II: The citizens of each province shall be entitled to all privileges and immunities of citizens in the several provinces.

A person charged in any province with treason, felony, or other crime, who shall flee from justice, and be found in another province, shall on demand of the executive authority of the province from which he fled, be delivered up, to be removed to the province having jurisdiction of the crime.

No Person held to service or labor in one province, under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due.

Section III: New provinces may be admitted by the Parliament into this Commonwealth; but no new province shall be formed or erected within the jurisdiction of any other province; nor any province be formed by the junction of two or more provinces, or parts of provinces, without the consent of the legislatures of the provinces concerned as well as of the Parliament.

The Parliament shall have power to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the Commonwealth; and nothing in this constitution shall be so construed as to prejudice any claims of the Commonwealth, or of any particular province.

Section IV: The Commonwealth shall guarantee to every province a democratic and representative government, and shall protect each of them against invasion; and on application of the legislature, or of the executive (when the legislature cannot be convened) against domestic violence.

Article V

Section I: The Parliament, whenever two thirds of both Houses shall deem it necessary, shall propose amendments to this constitution, or, on the application of the legislatures of two thirds of the several provinces, shall call a convention for proposing amendments, which, in either case, shall be valid to all intents and purposes, as part of this constitution, when ratified by the legislatures of three fourths of the several states, or by conventions in three fourths thereof, as the one or the other mode of ratification may be proposed by the Parliament; provided that no amendment which may be made prior to the year 1808, shall in any manner affect the first and fourth clauses in the ninth section of the first article; and that no province, without its consent, shall be deprived of its equal suffrage in the Senate.

Article VI

Section I: All debts contracted and engagements entered into, before the adoption of this constitution, shall be as valid against the Commonwealth under this constitution.

This constitution, and the laws of the Commonwealth which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the Commonwealth, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the Judges in every province shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any province to the contrary notwithstanding.

The Senators and Representatives to the House of Commons before mentioned, and the members of the several provincial legislatures, and all executive and judicial officers, both of the Commonwealth and of the several provinces, shall be bound by oath or affirmation, to support this constitution; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the Commonwealth.

Article VII

Section I: The ratification of the conventions of eleven provinces, shall be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the provinces so ratifying the same.

Last edited:

Deleted member 9338

Article VII

Section I: The ratification of the conventions of thirteen provinces, shall be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the provinces so ratifying the same.

So when it say 13 provinces, does this mean that Florida and Canada were not part of this?

Section I: The ratification of the conventions of thirteen provinces, shall be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the provinces so ratifying the same.

So when it say 13 provinces, does this mean that Florida and Canada were not part of this?

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

That’s an oversight, will correct in a bit.Article VII

Section I: The ratification of the conventions of thirteen provinces, shall be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the provinces so ratifying the same.

So when it say 13 provinces, does this mean that Florida and Canada were not part of this?

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

After reviewing the last chapter and cleaning up small errors (a few instances where I mentioned the United States instead of Commonwealth, etc), I actually realized I misread your question. In OTL, it took nine of the thirteen states to ratify the Constitution. As Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and Cape Breton Island are all provinces of the newly minted Commonwealth, so it'd take 11 out of 17 provinces.Article VII

Section I: The ratification of the conventions of thirteen provinces, shall be sufficient for the establishment of this constitution between the provinces so ratifying the same.

So when it say 13 provinces, does this mean that Florida and Canada were not part of this?

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

The Governor-General would represent the King, so there’s no need for another crossing.As a reminder, at this point (1785) Franklin may be the oldest man in the Colonies. If he has to get on a ship to be approved by the King, he may be coming home in a box.

Deleted member 9338

7 out of 68 is respectable for the Republicans. I see Patrick Henry being a king maker. My bet is he goes with Jefferson.

Nazi Space Spy

Banned

At the advice of @Thomas1195, I'm going to retcon the last update. I'll get it up tonight or tomorrow.

Threadmarks

View all 26 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter XVIII: The Franklin Ministry & the Colombian collapse. Chapter XIX: The Northwest War & the French Revolution's early stages. Chapter XX: First in the Hearts of his Countrymen. Chapter XXI: The 1790 Federal Election Chapter XXII: Liberte, Egalite, Fraternite Chapter XXIII: Westward Ho! Chapter XXIV: The Haitian Revolution Chapter XXV: The early Industrial Revolution in America.

Share: