No worries, I'm very much enjoying this TL.Brilliant input. I didn't know about that truthfully.

And thanks too for the compliment.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Emerald of The Equator: An Indonesian TL

- Thread starter SkylineDreamer

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 209 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

22.3. The Great Urbanization: Expansive City-Building 22.4. The Great Urbanization: The Big Three Ethnicities Preview 22.5. The Great Urbanization: Papua and Madagascar 22.6. The Great Urbanization: Stories Independence Day 2023 Edition 22.7. The Great Urbanization: ABRI 23.1. The Fragile Coalition: Prologue 23.2. The Fragile Coalition: Premier CandidatesJust telling, I'm not gone y'all. It's been a tough two weeks (internship, assignments, etc..), I promise to post something by the end of this week.

Just telling, I'm not gone y'all. It's been a tough two weeks (internship, assignments, etc..), I promise to post something by the end of this week.

Take your time, go finish your responsibilities first. 😄

21.6. Race of 1988: Wait what?

Cukup Dua Periode

25th November 1987 was the last day of presidential candidate registration. The day was longed for by everyone, not just the dilemma under the new premiership, but also it answered the ultimate problem Indonesians questions; Will the president rerun?

Looking at the past, presidential elections seldom consumed time. First, the number of parties are particularly limited with lesser candidates willing to nominate. Second, before Subandrio the Indonesian presidents are naturally ascended, not elected. Therefore, the race seemed less about the clash of ideologies, mere personal backgrounds. At this time, the frail 73-year-old Subandrio had long gone its perquisites. Every Indonesian had been asking the president about 1988. But when questioned about it, Subandrio had ignored every one of them. Many speculated Subandrio waited until the last second to see who his challengers are. Some others argued his questionable popularity has been refraining him for reelection.

For the last 10 years, the president’s popularity has been classified into two different eras of his lifetime. One was his time as the closest aide of Sukarno, one was him as the senior partner of LKY. As foreign minister, he helped push Sukarno’s agenda to the international stage, despite personally objecting to the Australian Aggression. He had similar views to Sukarno’s idea of Indonesia, which made him the diplomat he is. Subandrio was zealous on increasing the livelihood of Indonesians; he yet failed to discover how. Thus, Subandrio pursued decades of ideological viewpoints, one he supported on LKY’s liberalism strategy. Subandrio’s premiership in the 1970s was passing, but it marked the initial stages of Indonesian betterment, such as the reorganization of education, housing surplus, national integration, and many others. After his ascendance to the presidency, his policies are dwarfed by LKY’s more controversial policy but remained popular by LKY’s overwhelming bequest.

As cited to be the remaining defender of the old PPP system, President Subandrio stayed as the questionable, yet necessary candidate to unite the PPP. That factored from the president’s overwhelming influence in high levels of the PPP party, despite Barisan Progresif have begun opposing. Many of these reasons came from the naïve hopes of Emil Salim and many others with the president’s tenure. As many speculated, President Subandrio could be the only band-aid for the clash of the ideologues. Unfortunately, his insecurity spoiled his good image. After the slow distrust with LKY’s Malacca Faction, President Subandrio thwarted the PPP into internal division. He was an indirect accomplice of Mahathir’s “coup”, thus disdained by the progressives. His attempt to resurface the Nonaligned Movement fared poorly, his education policy starved with budget deficits from the effects of political instability. In response, Subandrio had doubled down on Mahathir’s narrative of Malay privilege, a contradiction of his statements a few decades ago.

25th November 1987 was the last day of presidential candidate registration. The day was longed for by everyone, not just the dilemma under the new premiership, but also it answered the ultimate problem Indonesians questions; Will the president rerun?

Looking at the past, presidential elections seldom consumed time. First, the number of parties are particularly limited with lesser candidates willing to nominate. Second, before Subandrio the Indonesian presidents are naturally ascended, not elected. Therefore, the race seemed less about the clash of ideologies, mere personal backgrounds. At this time, the frail 73-year-old Subandrio had long gone its perquisites. Every Indonesian had been asking the president about 1988. But when questioned about it, Subandrio had ignored every one of them. Many speculated Subandrio waited until the last second to see who his challengers are. Some others argued his questionable popularity has been refraining him for reelection.

For the last 10 years, the president’s popularity has been classified into two different eras of his lifetime. One was his time as the closest aide of Sukarno, one was him as the senior partner of LKY. As foreign minister, he helped push Sukarno’s agenda to the international stage, despite personally objecting to the Australian Aggression. He had similar views to Sukarno’s idea of Indonesia, which made him the diplomat he is. Subandrio was zealous on increasing the livelihood of Indonesians; he yet failed to discover how. Thus, Subandrio pursued decades of ideological viewpoints, one he supported on LKY’s liberalism strategy. Subandrio’s premiership in the 1970s was passing, but it marked the initial stages of Indonesian betterment, such as the reorganization of education, housing surplus, national integration, and many others. After his ascendance to the presidency, his policies are dwarfed by LKY’s more controversial policy but remained popular by LKY’s overwhelming bequest.

As cited to be the remaining defender of the old PPP system, President Subandrio stayed as the questionable, yet necessary candidate to unite the PPP. That factored from the president’s overwhelming influence in high levels of the PPP party, despite Barisan Progresif have begun opposing. Many of these reasons came from the naïve hopes of Emil Salim and many others with the president’s tenure. As many speculated, President Subandrio could be the only band-aid for the clash of the ideologues. Unfortunately, his insecurity spoiled his good image. After the slow distrust with LKY’s Malacca Faction, President Subandrio thwarted the PPP into internal division. He was an indirect accomplice of Mahathir’s “coup”, thus disdained by the progressives. His attempt to resurface the Nonaligned Movement fared poorly, his education policy starved with budget deficits from the effects of political instability. In response, Subandrio had doubled down on Mahathir’s narrative of Malay privilege, a contradiction of his statements a few decades ago.

“There is no Chinese Indonesian, Indian Indonesian, Native Indonesian. Only Indonesian. We bleed red, eat rice and struggle evenly in this wretched war. Should we work together as an Indonesian, not only we can plow through this struggle, but win it as well.”

Subandrio during an exclusive Tempo Interview about the Australian Aggression, 15th September 1961

Subandrio’s regime indeed suffered a malaise nearing the election year, yet the popularity he received was possible for a campaign run. His positive legacy, truthfully LKY’s brainchild, continued to appease few hearts as decent achievements. In recent October surveys, many had shown favourable opinions to the president relative to other candidates. Most of them defended the president of the “downs” in his presidency as temporary, thus entrusting him for reelection. Few radicals, in Barisan Progresif and Barisan Kesejahteraan as an example, yet presented merely less favourable than outright opposed. From all of this, Subandrio did not seek for election in an instance.

Subandrio’s silence sparked hope for other challengers to rise. Almost every party outside the PPP has suggested their idols to run for president. Still, the presidency was a difficult task, many chose not to run for president. Gus Dur was enticed by NU compatriots but rejected in the final seconds. PNI-R attempted to promote Ali Sadikin, but he preferred running in the Parliament. In the end, only one stood against Subandrio, Guntur Sukarnoputra.

Unlike most parties who campaign party ideologues, the PPI had been promoting Guntur and all his policies. The 1988 Manifesto was published on all party pamphlets, broadcast on any radio station PPI could find. Guntur was meticulous to clear any signs of pro-communist in his statements, akin to opposition from the progressive PPP wing. He also campaigned against the Bumiputera policy, which ended the friendship between Mahathir’s populist wings. After five years, the candidate had aimed for a compromise candidate, an alternative against the “madness” he expressed which is the Bumiputera plan. In his speeches, he reinforced his disgust with the policy. The manoeuvre was so cunning because Subandrio must choose to adhere to said policy should he try running.

Guntur may be promoted as a great challenger of President Subandrio, yet he remained circled with various rivals, as other parties were reluctant to cooperate with him. He was infamous for his authoritative measures in his internal party, much to the disappointment of other’s proposed coalitions. He vilified many of the other’s officials, like Ali Sadikin and Try Sutrisno, to be the reason for Sukarno’s fait accompli resignation. Under his remarks, he also disliked the Malayan establishment, stating the true spirit of Indonesia stemmed from the spirits of ’45 which Malaysians never participated. Nevertheless, he sought for the progressives of the PPP, all of whom teetering on party loyalty.

In November, frequent visits happened in the Presidential Palace. Many of them are the PPP’s highest public officials, progressive or populist, that wished Subandrio to be the image. Emil Salim, the leader of the Barisan Progresif, wished the President to be a middle-ground between pro-LKY and pro-Mahathir, therefore maintaining unity. On the other hand, Premier Mahathir had tried boosting Subandrio to Kesejahteraan Rakyat, determining a split of the party. These visits ended up with empty hands though, as the President had his lips closed on confirmation. That is until 11th November 1987.

That Wednesday, the President was flying on his trip to Balikpapan when he suddenly convulsed. The president suffered a second deadly stroke. When the plane landed in Suryadarma Airport Jakarta, the president was rushed to RS Gatot Subroto, with reports on the ambulance that he continues convulsing. News about the president’s health stayed dark until the 13th of November when RS Gatot Subroto officials finally declared the president to be resuscitated from a two-day coma. The media rushed in for further questions which the doctors blocked them. From later reports of his well-being, the President had massive stress on his work, thus causing the repetitive strokes this year. The recent coma reemerged the question of the President’s reelection, now citing health as the most critical factor.

On the first day of next week, President Subandrio has returned to the Presidential Palace, greeted the cameras in the process. Despite a return, the president seemed to have a significant change in his heart, reasons still unknown. Unlike previous attempts that he would undermine the pro-LKY’s sympathizers on his words, his public conference remained neutral on those matters. His efforts have drawn to the tough NAM revival, a personal reflection of his Sukarno-ism tendencies. Moreover, he shook Indonesia to the core after his November speech, a piece that would remain prevalent in Indonesian history.

As much as I would want my presidency to continue. The last nine years has been a great adventure filled with obstacles and challenges. Back in 1978, as the former Premier of the nation, I had hoped for changes, rapid ones. The spirit of then was passionate, flooded to the hearts of the nation, replenish them with a new hope for better Indonesia. Nowadays, that same man had turned into an old me, enduring questionable choices, suffering repetitive health problems. I tried reinvigorating myself with new objectives, one that fulfill the gap left by the previous years of my presidency. Yet, with less than a year of evaluation, I find myself on a pickle, realizing that many of my personal ambitions can be destructive to others.

The last episode of my health problems was, arbitrarily, an indirect blessing derived from Allah. For once, I looked upon my deeds, actions, consequences additionally. I transformed Indonesia’s education, albeit slow-paced. I solved the housing crisis with thousands of new homes build a remarkable achievement should I remind you the government did not lend debts. My premier had tweaked the root systems of Indonesia’s bureaucracy, forming a simplified and practical version which I remained grateful for. Finally, Premier Musa Hitam has provided the best regulation in history, providing a compromise between the undoubted demands of better livelihood and the relentless ventures of the enterprise.

Under these considerations, I felt my presidency as one chapter of Indonesians history. This, for me, is the era of Indonesia’s great growth, progress and increments on the global order. Nonetheless, all eras will end, I think my era ends soon. In conclusion, it’s time for Indonesia to open a new chapter, whatever that will be.

As a result, I will not run for president in this 1988 election. I hope my concerns receive well by all sides and the entire brethren of Indonesia. Cukup dua periode, Indonesia butuh pemimpin baru.

Besides his rejection of reelection, President Subandrio gave an honest response to the people of Indonesia about his remaining years in office. He declared the Nonaligned Movement as his main objective, a stable friendship between the UASR, Yugoslavia, and the remains of the old movement. Moreover, he would give the proportionate response to the crisis in Vietnam in a later broadcast. Abiding the constitution, he admitted his past for intervention in the premiership sector, some even disturb the premier’s work. He promised to concentrate on foreign affairs, one Indonesia is lacking greatly. Subandrio’s change of demeanour surprised the media, even more, when he continued about his wishes of the last term about separation of powers. He stated even though the president and premier should show deliberation in governmental affairs, both leaders must honour the separation of duty.

Promises made, promises kept.

I will finish this chapter with the true candidates of the 1988 election, but lemme post this big boy out.

2022 Hiatus

Hello all, it's been more than a month. The most prolonged absence I've been not in this TL, but the ATL community. Life is tough, assignments, exams and projects are everywhere. The last month being a prick to me.

Luckily, exams are over, I have almost a three-month break until August (there's still other extra-co stuff, but that's manageable).

So sorry for dear viewers to think this TL is dead, it definitely isn't, as I promised myself to complete this in my past. Give me three or four days to look at this TL again, expect a new post by late next week.

Luckily, exams are over, I have almost a three-month break until August (there's still other extra-co stuff, but that's manageable).

So sorry for dear viewers to think this TL is dead, it definitely isn't, as I promised myself to complete this in my past. Give me three or four days to look at this TL again, expect a new post by late next week.

21.6. Race of 1988: And thus there were two candidates

The Honor of Candidacy

Restarting a TL accidentally from hiatus is like a train steaming after a stop; It needs time to regain normal speed. Moreover, as I looked at my timeline again, I notice a few of my TL "points" better with the new options, thus subsequently changing my initial outline of this TL. This, truthfully, has been one example.

Expect more "back-and-forth" politics in 1988, next post should look at an unexpected (yet pleasing) turn of events.

For every election in this era of Indonesian history, there have been “firsts”. This election signified the first election in which a second-term incumbent declined for reelection. For scholars in the Western World, it symbolized Indonesia’s struggle with leaders quenched their desire for the cycle of democracy. For formerly Indonesian intellectuals, it marked the breakup of the incumbent party. Some modern scholars might argue the end of “stable” Indonesian regimes, an unfortunate outcome which 1988 may be the triggering point. Until Subandrio’s refusal, 1988 candidates were a mere two, Subandrio and Guntur Sukarnoputra. Notable others, like Try Sutrisno, Gus Dur and Ali Sadikin have all objected to candidacy because of past events, particularly 1983 Umar’s humiliation. The defeat of Umar reminded people that the most prominent politician in the party may not be the most popular with the people. Moreover, only Guntur’s PPI has shown total discontent towards PPP, the others “dangling their feet” to the incumbent. After Subandrio announced it, however, many of whom regretted not seeking the office.

Indonesian presidency, in the meantime, also carried one fundamental superstition everyone believes. From Sukarno, Nasution and Subandrio, the two successors were either “appointed” or “recognized” by the Proclamator. Nasution has been a personal choice of Sukarno during the troubled times, while Subandrio was Sukarno’s aide-de-camp during the 60s. Hence, it has brought many “perspectives” supporters for all aisles wished to promote. Naturally, Guntur had the highest legitimacy from his bloodline, but Subandrio supporters ridiculed him for losing the 1983 election. After Subandrio’s declination, it was hard to find another replacement.

Kesejahteraan Rakyat of the PPP pushed their first move by proclaiming Mahathir Mohammad as president. Albeit no wishes from the Premier, his ardent supporters have happily hoped for this move, a golden opportunity one should seek. The politicians disagree, as Mahathir’s candidacy will weaken his influence in the Parliament, thus policies like Bumiputera and various labour laws might lose into obscurity. Less than ten days before the deadline, the wing decided to lobby the moderate candidate. That candidate, horror to Barisan Progresif, was General Susilo Sudarman.

General Susilo Sudarman, renowned for his actions as a “guerilla general”, appease the population as less divisive than any Kesejahteraan Rakyat candidates, yet have individual opinions supporting Mahathir’s base. He was the only general lucky to involve in military actions in Mozambique. That said, General Susilo Sudarman suffered from that popularity, as Mozambique eventually surrendered to despotic leaders. The general thus blamed the United States to agonize the native Africans so far as to reject democracy. The general lacked an authoritarian demeanour, and willingness to rest decisions on expert politicians, a perfect candidate for Mahathir Mohammad.

As Defense Minister, General Sudarman had no consequential controversies that could damage his image, as Try Sutrisno had. He was close to the President and garnered the general the “legitimate” claim for the presidency. His cunning and diplomatic vigour also appealed to many moderate PPPs, alienating the Barisan Progresif Pro-LKY wing as the “radical” one. In conclusion, the general was the best option for Kesejahteraan Rakyat's success. Mere days after a deliberate brainstorming from the populist end of the PPP, Mahathir Mohammad urged General Sudarman as the new candidate for the presidency. Sudarman approved after a night, declaring his candidacy on the 20th of November 1987. In his speech, he disclosed the continuation of the President’s policies: Non-Aligned Movement, promise to reform labour, and other Subandrio-ism policies.

The candidacy of Susilo Sudarman drained all optimism on Barisan Progresif. The general’s small dispute with LKY before had discouraged pro-LKY politicians into his close circle. His compassionate attitude (unlike most generals authoritatively stern), too harmed Barisan Progresif in moderate PPP voters. Musa’s absence in federal politics killed enthusiasm for this party, as neither had any alternative on any charisma and experience to counter Susilo Sudarman. Days wreak the liberal wing on how to reclaim pre-1988 influence. Emil Salim, the faction leader, tried appeasing the new general. His initial intentions preferred Susilo Sudarman as the “unifying” candidate for PPP, therefore again wished for balance between Barisan Progresif and Kesejahteraan Rakyat.

Mere days before the day, Emil Salim visited presidential candidate Susilo Sudarman at his residence. They expressed cordial greetings at each other, obvious publicity to recognize PPP’s attempts to unify itself after months of obstacles. There, two conflicting minds have tried to renegotiate. Mahathir’s faction meant an overhaul of labour policies, one of which increased union presence in the country. With restraint foreign policy and domestic look, General Susilo Sudarman supported these ideas from experiences of failed expeditions. Unbeknownst to the party and public, General Susilo Sudarman expressed doubts about Bumiputera's policy, declaring it inherently wrong within Pancasila. The statement calmed Emil Salim. Furthermore, he honoured LKY for all progress he has created in Indonesia. He promised to be as moderate as possible, curtailing any radical attempts both from Kesejahteraan Rakyat and Barisan Progresif, a proposal Emil Salim agreed. Just hours after his visit with Emil Salim, General Susilo Sudarman approached Mahathir Mohammad. Many speculated that Susilo Sudarman “give some sense” that the Bumiputera policy was too radical for the entire nation, also mediating with the opposing wing will be better as previous months of riots and chaos engulfed the nation. The General, meanwhile, affirmed Labour rights, claiming that Indonesia’s path to progress includes modernization, that being unionization akin to Western nations in the height of the industry. Just hours before the registration deadline, the General proclaimed his candidacy speech.

Indonesian presidency, in the meantime, also carried one fundamental superstition everyone believes. From Sukarno, Nasution and Subandrio, the two successors were either “appointed” or “recognized” by the Proclamator. Nasution has been a personal choice of Sukarno during the troubled times, while Subandrio was Sukarno’s aide-de-camp during the 60s. Hence, it has brought many “perspectives” supporters for all aisles wished to promote. Naturally, Guntur had the highest legitimacy from his bloodline, but Subandrio supporters ridiculed him for losing the 1983 election. After Subandrio’s declination, it was hard to find another replacement.

Kesejahteraan Rakyat of the PPP pushed their first move by proclaiming Mahathir Mohammad as president. Albeit no wishes from the Premier, his ardent supporters have happily hoped for this move, a golden opportunity one should seek. The politicians disagree, as Mahathir’s candidacy will weaken his influence in the Parliament, thus policies like Bumiputera and various labour laws might lose into obscurity. Less than ten days before the deadline, the wing decided to lobby the moderate candidate. That candidate, horror to Barisan Progresif, was General Susilo Sudarman.

General Susilo Sudarman, renowned for his actions as a “guerilla general”, appease the population as less divisive than any Kesejahteraan Rakyat candidates, yet have individual opinions supporting Mahathir’s base. He was the only general lucky to involve in military actions in Mozambique. That said, General Susilo Sudarman suffered from that popularity, as Mozambique eventually surrendered to despotic leaders. The general thus blamed the United States to agonize the native Africans so far as to reject democracy. The general lacked an authoritarian demeanour, and willingness to rest decisions on expert politicians, a perfect candidate for Mahathir Mohammad.

As Defense Minister, General Sudarman had no consequential controversies that could damage his image, as Try Sutrisno had. He was close to the President and garnered the general the “legitimate” claim for the presidency. His cunning and diplomatic vigour also appealed to many moderate PPPs, alienating the Barisan Progresif Pro-LKY wing as the “radical” one. In conclusion, the general was the best option for Kesejahteraan Rakyat's success. Mere days after a deliberate brainstorming from the populist end of the PPP, Mahathir Mohammad urged General Sudarman as the new candidate for the presidency. Sudarman approved after a night, declaring his candidacy on the 20th of November 1987. In his speech, he disclosed the continuation of the President’s policies: Non-Aligned Movement, promise to reform labour, and other Subandrio-ism policies.

The candidacy of Susilo Sudarman drained all optimism on Barisan Progresif. The general’s small dispute with LKY before had discouraged pro-LKY politicians into his close circle. His compassionate attitude (unlike most generals authoritatively stern), too harmed Barisan Progresif in moderate PPP voters. Musa’s absence in federal politics killed enthusiasm for this party, as neither had any alternative on any charisma and experience to counter Susilo Sudarman. Days wreak the liberal wing on how to reclaim pre-1988 influence. Emil Salim, the faction leader, tried appeasing the new general. His initial intentions preferred Susilo Sudarman as the “unifying” candidate for PPP, therefore again wished for balance between Barisan Progresif and Kesejahteraan Rakyat.

Mere days before the day, Emil Salim visited presidential candidate Susilo Sudarman at his residence. They expressed cordial greetings at each other, obvious publicity to recognize PPP’s attempts to unify itself after months of obstacles. There, two conflicting minds have tried to renegotiate. Mahathir’s faction meant an overhaul of labour policies, one of which increased union presence in the country. With restraint foreign policy and domestic look, General Susilo Sudarman supported these ideas from experiences of failed expeditions. Unbeknownst to the party and public, General Susilo Sudarman expressed doubts about Bumiputera's policy, declaring it inherently wrong within Pancasila. The statement calmed Emil Salim. Furthermore, he honoured LKY for all progress he has created in Indonesia. He promised to be as moderate as possible, curtailing any radical attempts both from Kesejahteraan Rakyat and Barisan Progresif, a proposal Emil Salim agreed. Just hours after his visit with Emil Salim, General Susilo Sudarman approached Mahathir Mohammad. Many speculated that Susilo Sudarman “give some sense” that the Bumiputera policy was too radical for the entire nation, also mediating with the opposing wing will be better as previous months of riots and chaos engulfed the nation. The General, meanwhile, affirmed Labour rights, claiming that Indonesia’s path to progress includes modernization, that being unionization akin to Western nations in the height of the industry. Just hours before the registration deadline, the General proclaimed his candidacy speech.

For the last months of this nation, uncertainty has grown under the party of the incumbent. Riots between two conflicting factions under the same party ridicule us in the eyes of the people, opening our adversaries’ opportunities. I can assure you this party has experienced decades of maturity, with two great opposing minds towards the same goal, improving the prosperity of Indonesians. We have one faction claiming labour as the key, to improving laws protecting workers and farmers. The other faction claimed industrial conglomerates as the key, to improving Indonesia’s productivity on the international stage. However, let me remind everyone, all Indonesians, PPP especially, that things that unite us are far greater than things that divide us. We believe in improving the prosperity of our citizens, reclaiming our status as a formidable power, and also tread the delicate balance between adhering to the West and the Oriental East. As a matter of fact, that has been who we are, Indonesians. As the wedge between two massive oceans and two great continents, we have become the bottleneck of trade and civilization. That’s why we have been so tolerant of each other because our legacy has defined us so. Tolerance has been our greatest gift to humankind. We have united in many things grander than petty skin colour, our struggles against imperialism have been one example. From our previous generations, glorious heroes have died for the survival of this federation, many of whom had no care of race, religion, and local tradition.

I mention tolerance to remember us of recent events of intolerance within our party. What we need in 1988 is a unifying face, not disunity. I believe PPP has great politicians, but they forget the factor which drives PPP successful in the first place: unity. With my candidacy, I hope I can be the middle ground between two conflicting factions within our party, harnessing as the true successor of Subandrio, paving way for another path for PPP’s chance to reform Indonesia.

-Susilo Sudarman 1987

The General sparked new hope in moderate supporters of PPP (mostly urban dwellers in Java and Sumatra), the pivotal populations that win Subandrio the presidency. Meanwhile, fringe groups on both sides (Barisan Progresif and Kesejahteraan Rakyat) expressed disappointment in another “conciliatory” candidate for PPP. Even, though Emil Salim was the only one satisfied, Mahathir Mohammad was a little displeased by his announcement. Still, he realized that PPP’s survival may have this as the only option, with Guntur gaining big steam under the disunited PPP.

Restarting a TL accidentally from hiatus is like a train steaming after a stop; It needs time to regain normal speed. Moreover, as I looked at my timeline again, I notice a few of my TL "points" better with the new options, thus subsequently changing my initial outline of this TL. This, truthfully, has been one example.

Expect more "back-and-forth" politics in 1988, next post should look at an unexpected (yet pleasing) turn of events.

Last edited:

21.7. Race of 1988: Legislative Results

The Campaign Messages

The uncertainty of 1988 was unlike any other election before, it evolved into the most rugged, yet quite pathetic. Began with the assassination of the Premier in August 1986, the labour issue that lingered throughout 1987, PPP’s internal conflicts nearing 1988 and the lingering fate of SEATO and Spratly League. In contrast to the era of Nasution and Sukarno (most of them being deliberate constants in growth), Subandrio’s has been the drastic ups, then the abrupt downs. The downs were the most evident in this decade, but the ups should not be neglected as so. One of them was the strange economic uptick at the beginning of 1988.

As the presidential campaigns of both candidates began in January 1988, establishment General Susilo received the positive boost it needed because of the surprising economic return from the last quarter’s report. The labour dispute has dissipated mostly during that time, bringing productivity higher than pre-crisis levels, enhancing the economy once more with astonishing 7.5% growth in capital. Most of the workers have settled old wounds with industrial owners, finalising the malaise of 1987. It garnered a mixed response from the incumbent PPP. Barisan Progresif was disgruntled with the populist’s flattering contribution to the Indonesian economy, hence their popularity decreased in the national vote. Contrary to the popular belief, Kesejahteraan Rakyat also suffered uneasiness, as the healing economy tarnished any chance of Bumiputera policies enacted, again dispirited hardcore populists like Mahathir Mohammad. Fortunately, this gift can’t be more specifically aimed at General Susilo Sudarman, the Subandrio-ist successor.

The uncertainty of 1988 was unlike any other election before, it evolved into the most rugged, yet quite pathetic. Began with the assassination of the Premier in August 1986, the labour issue that lingered throughout 1987, PPP’s internal conflicts nearing 1988 and the lingering fate of SEATO and Spratly League. In contrast to the era of Nasution and Sukarno (most of them being deliberate constants in growth), Subandrio’s has been the drastic ups, then the abrupt downs. The downs were the most evident in this decade, but the ups should not be neglected as so. One of them was the strange economic uptick at the beginning of 1988.

As the presidential campaigns of both candidates began in January 1988, establishment General Susilo received the positive boost it needed because of the surprising economic return from the last quarter’s report. The labour dispute has dissipated mostly during that time, bringing productivity higher than pre-crisis levels, enhancing the economy once more with astonishing 7.5% growth in capital. Most of the workers have settled old wounds with industrial owners, finalising the malaise of 1987. It garnered a mixed response from the incumbent PPP. Barisan Progresif was disgruntled with the populist’s flattering contribution to the Indonesian economy, hence their popularity decreased in the national vote. Contrary to the popular belief, Kesejahteraan Rakyat also suffered uneasiness, as the healing economy tarnished any chance of Bumiputera policies enacted, again dispirited hardcore populists like Mahathir Mohammad. Fortunately, this gift can’t be more specifically aimed at General Susilo Sudarman, the Subandrio-ist successor.

General Susilo Sudarman, 1988

Other factors that cause this growth may be foreigners’ confidence, especially with Indochina War nearing its end, and Japan’s continuous economic growth. The issues in the United States, Wars in Pakistan, and Africa also Europe’s serendipity did little mark on the Asia-Pacific economy. Moreover, with Indonesia as the most appropriate choice for Japanese importers (considering all options lack economic power), Indonesia was again the exclusive beneficiary of Japan’s economic miracle. International events may also be involved in this strange phenomenon. The Suez Canal access to the Europeans has been rather safe for commerce, as opposed to previous hostilities from the Israeli exodus. Consequently, European trading has had a steady increase over the last year, improving Indonesia’s trading opportunities abroad.

Daihatsu factory in Bekasi, one of the largest employers in Jakarta Greater Region'

The apparent campaign message for General Susilo Sudarman, despite protests within Kesejahteraan Rakyat, was the continuation of Subandrio’s balance between meeting the economic demands of industrial growth as well as fulfilling the needs of working-class Indonesians. He expressed this balance with a concept of a ‘dual system’, one that pioneered Sudarman’s core campaign policies. He believed cities and rural can be mutual on each other while retaining their unique attributes. This disparity may be contextualized by uneven fiscal policy, different electoral systems, or custom education curriculums. His “One Country Two System” [1] policy gathered moderates en masse, especially in comparison to Guntur’s policy. Listening to Subandrio and moderate PPP politicians, he abstained himself from public view to let the economy rebound his popularity. His social stances softened towards Barisan Progresif, announcing similar rhetoric of avoiding Bumiputera policies while emphasizing diversity as a strength. Again, this non-conformist campaign resonated with many of Sudarman’s campaigns, as proven by his advocacy speeches of the current system.

General Susilo Sudarman was in a dilemma as he opposed Japan’s remarkable leverage in Indonesia but realized the importance of Japan in Indonesia’s current growth. Barisan Kesejahteraan also demanded more independence from Japan, diversifying imports to the United States or Europe. Nevertheless, the general relinquished his old prejudice, and thus embraced Japan as Indonesia’s most valuable partner. He charmed moderates of the PPP who enjoyed all that is, while diehard Barisan Progresif and Kesejahteraan Rakyat expressed discontent. In the end, his foreign promises were those Subandrio wished to continue, plans like reviving the Asia-African spirit, improving Third World standing and Politik bebas aktif. In the end, Sudarman opted for minimal fresh ideas, and let Subandrio-ism take the mantle.

The lack of freshness in Sudarman’s policy gave mileage for Guntur to adopt more revolutionary ones, for better or worse. As many of Sudarman policies were, at most, a “moderate” version of Guntur’s, his campaigners thought banking on radical versions may invigorate the PPI base. Therefore, albeit Guntur was advocating similar policies to the general, he gained the upper hand with sound reforms to the PPP. Guntur’s supporters have started calling Sudarman a “status-quo bootlicker”, a slander used to dissuade independents. This had also led liberal hardcore PPI factions, Barisan Progresif, to bank slightly in favour of the Proclamator’s son. This, in return, made the 1988 election a pathetic choice of candidates for the general populace would choose either the pragmatic or the radical, with policies more or less identical.

Guntur and Mega during a fundraising event, 1987

His most publicized policy is universal basic healthcare for all Indonesians. He wished the government to subsidize basic healthcare programs, such as subsidized medicine for the poor, subsidized doctor visits for the elderly above 65, with better public health insurance to cover everyone[2]. Yet, to appease the liberals, he advocated a slight “ranked” insurance level, providing more wealthy Indonesians with better healthcare options. It would increase the health budget by almost 156%, therefore Sudarman attacked Guntur for risking the national budget. Guntur insisted, even countering Sudarman’s attacks with his mediocrity on every policy.

The PPI, to attract the PNI-R base, supported a national increase in the federal defense, decrying the need for Indonesia’s armed forces on such vast territories of Indonesia. Piracy in Madagascar, albeit manageable, has been Guntur’s main concern about Indonesia’s standing. He stated while Indonesia will withstand current raids, the government’s inaction would encourage those pirates for further opportunities. He also pointed out that the Chagos Archipelago, former British Indian Ocean Territory, may be further extended as an Indonesian base between the proper mainland and Madagascar. While Sudarman interjected such an offer, believing the current state of world affairs was not as urgent for Indonesia’s expanded armed forces, Guntur immediately launched an attack claiming Sudarman was dependent on American forces.

Guntur’s other policy, his base’s red meat, was the organization of labour unions in Indonesia. He emphasized all developed nations were birthed from a strong union [3], so Indonesia should own as well. Guntur applauded the labour efforts on compromising with the Premier for the 1987 Labour Law. The appeal did damage a little for the progressive voters because of the trauma from previous pro-labour demonstrations. Guntur, already aware of the backlash, defended his ideals towards the liberals, claiming labour unions in the US, France and Germany were paramount for the nation’s greatness. He further strengthened his argument, claiming labour unions would benefit every Indonesian rising from critical poverty, and elevate to “middle class” (although the PPI refrain from using the term of its toxicity on communist supporters).

PPI propaganda translated "100% Merdeka" as "100% Labour Unions", might not be so in retrospect or from the illustration alone.

Guntur’s foreign policy take a progressive turn as he pushed for a more diplomatically active Indonesia. Indonesia under his presidency will be inspirational, like how Sukarno’s charisma flowed globally from his speeches during foreign visits and the annual UN congress. He remained a staunch advocate for NAM’s revival, although he downplayed the ‘non-aligned’ ideologue in contrast to Sudarman. Contrary to popular belief, his main objective was the revival of the Spratley League and SEATO, claiming these organizations as Indonesia’s major dominance apparatus [4]. Although South Vietnam was turning the tide, Guntur attacked Subandrio and Sudarman for their refusal on aiding a close ally, giving even the hardcore communists within PPI significant criticism.

Overall, both candidates seemed to present a similar approach to policies, opinions, and approaches in almost all domestic policies. The stark difference in foreign policy, meanwhile, did possess a significant distinction between the two candidates. For Indonesians, one was too careful and pragmatic, the other radical and vigorous. The lack of direction in Sudarman gave PPP a chance for a broad coalition of moderates, while Guntur gave a significant boost to PPI’s vote, as well as appeals to certain aspects of the political spectrum.

Coalition Forms

Legislative Election would happen on Wednesday, 6 April 1988. Before that, the multi-party system of the legislative body opened new chances of a coalition, break, or bond, before the new 1988 government truly take place. Although previous projections of coalition bonds may shape public perspective on each party, the year surprised all expectations when all hell breaks loose with various parties expressing unforeseen friendships, rivalries, and even opposition. However, if one takes a closer look at their campaign policies, it was not impulsive as one may see.

The first surprise was how Guntur appealed to the PNI-R’s Ali Sadikin into a close relationship. The close bond emerged from Old Party’s ruthless opposition to PPP’s populist party after Bumiputera policy as a new campaign promise. With PNI-R’s civic nationalism, many politicians admitted Guntur to be more politically aligned rather than General Sudarman. Moreover, the PPI’s no monarchist appeal harnessed more love from Nusantara Faction. Guntur never expressed any disdain for incumbent monarchs, but Guntur’s idealism invoked the spirit within Nusantara supporters, the vigour that was lost after Nasution’s absence.

PUI, the party that Guntur sought in 1983, was not fond of PPI anymore in 1988. Gus Dur and Amien Rais may have invoked opposition against Bumiputera, but Sudarman’s moderate stance has appealed ulemas back against Guntur. Indeed, Guntur has assured the public that Islam will continue as a fundamental aspect of Indonesians, but his intention of separating church and state may dissuade religious supporters against him. Between a rock and a hard place, the PUI betrayed the planned PPI-PUI Coalition by Sudarman, forming the new Teruskan Coalition in early January 1988. In a public declaration, Amien emphasized PPP’s willingness to advocate Indonesia’s Islamism model as part of the candidate’s policies, a negotiation done between Amien, Gusdur, and Mahathir Mohammad.[5]

There is one new party entering the race, Partai Majelis Persatuan Muslimin, an Islamist party that originated in Depok, Pasundan State. Ustadz Abdul Ghafar from Depok has assumed leadership as the only party that emerged victorious with strict party regulations under the Indonesian federal constitution. However, his ideas fell flat on his constituents of Pasundan State, but a surprising enthusiasm arrived from Aceh, where hardcore Aceh Islamists were against NU and Muhammadiyah, and wished for a new branch of Islamic ideology in Indonesia.

Another intriguing turn of events was the changing leadership in Barisan Koalisi Daerah Timur. Lawrence G. Rawl, an American conglomerate in Timika [6], assumed great influence in the party’s leadership, ousting former Maluku secessionists from the high command. BKDT changed their policies, from advocating East provinces’ rights to extremely pro-liberal policies which Rawl has matured in. As this was a definite target for American growing immigrants across Papua, BKDT was, in one perspective, ousted by foreigners. The disappointed core Maluku supporters of BKDT fled for the remainder of the federal parties, but Tutut’s opportunist outlook may gather the upper hand on the residents. Politically, the new BKDT would align more towards progressive PPP, but they remained distant on joining the Teruskan Coalition.

Until the legislative election, Teruskan Coalition was the only coalition formally established as a political pact in the 1988 election. The potential of a competing coalition involving PNI-R and PPI was likely but went nowhere before the election ended. Partai Aliansi Melanesia, a regional Melanesian party in the Solomon Islands, have a significant boost from the Tragedy of Poroporo. Polls indicate PPP’s decline from the political turmoil in 1986 and 1987, while PPI and PUI were the biggest victories.

The Legislative Election

The results came as expected from poll analysts, without LKY and Subandrio, the PPP voters on Java fled to PPI. PNI-R, an interesting anomaly, managed to hold on with little loss, rather than PRD’s downfall from 83 seats to 36 allocated seats. The shift came from PRD’s policy aimed at specific promises, like ending forest fires in Eastern Sumatra, pro-Javanese immigration in Lampung and former BKDT’s Maluku base migration. In other areas that were Suharto stronghold, either moved to PNI-R or PPI. PUI was the biggest winner in this election and managed to double in size from religious folks in various states of Indonesia rallying for the party notably in Banjar, Jombang and Minang. PPI swept clean Java’s Northern coasts from Serang to Semarang, except for the Jakarta region PPP.

Although the BKDT, MAP (Melanesia) and PMPM (Islamists) did not receive 5% of the popular vote to get a seat in the Parliament, these parties manage to gather a deal with major parties (PPP, PNI-R and PUI respectively) to put their representative affiliation as these major parties first, before eventually registered themselves as their party. This tactic, known as "Nebeng-ism" has sprouted and flourished since 1988. Promises to the big party, like siding in legislation and others had happened so these candidates can proceed. Also, these small-party candidates have been very popular in their respective counties (Stanley Ann Dunham in North Papua as an example), so not giving them seats may give respective regional voters spite to main parties, eventually opposing them.

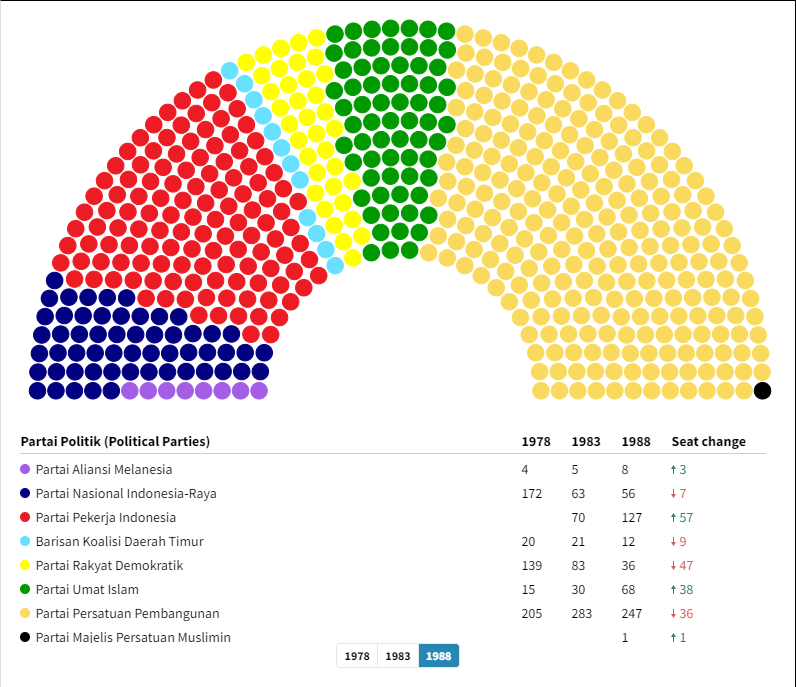

People's Representative Council of Indonesia (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Indonesia)

555 Seats

555 Seats

Melanesian Alliance Party (Partai Aliansi Melanesia) - 8 seats - 1.44%

Partai Nasional Indonesia - Raya (National Party of [Greater] Indonesia) - 56 seats - 10.09%

- Fraksi Nasionalis (Nationalist Faction) - 8 seats

- Fraksi Nusantara (Ali-Suryadino Faction) - 48 seats

Barisan Koalisi Daerah Timur (Eastern Coalition Front) - 12 seats - 2.16%

Partai Rakyat Demokratik (People's Democratic Party) - 36 seats - 6.49%

Partai Umat Islam (Islam People's Party) - 68 seats - 12.25%

- Fraksi NU (NU Faction) - 39 seats

- Fraksi Muhammadiyah (Amien Faction) - 29 seats

- Fraksi Hatta (Hatta Faction) - 2 seats

- Fraksi Kesejahteraan Rakyat (MelayuFaction) - 121 seats

- Fraksi Barisan Progresif (Malacca Faction) - 108 seats

- Fraksi Madagascar (Madagascar Faction) - 16 seats

People's Regional Council of Indonesia (Dewan Perwakilan Daerah Indonesia)

114 Seats

Melanesian Alliance Party (Partai Aliansi Melanesia) - 3 seats - 2.63%

Partai Nasional Indonesia - Raya (National Party of [Greater] Indonesia) - 17 seats - 14.91%

- Fraksi Nasionalis (Nationalist Faction) - 7 seats

- Fraksi Nusantara (Ali-Suryadino Faction) - 10 seats

Barisan Koalisi Daerah Timur (Eastern Coalition Front) - 3 seats - 2.63%

Partai Rakyat Demokratik (People's Democratic Party) - 9 seats - 7.89%

Partai Umat Islam (Islam People's Party) - 15 seats - 13.18%

- Fraksi NU (NU Faction) - 10 seats

- Fraksi Muhammadiyah (Amien Faction) - 5 seats

- Fraksi Hatta (Hatta Faction) - 1 seats

- Fraksi Kesejahteraan Rakyat (MelayuFaction) - 22 seats

- Fraksi Barisan Progresif (Malacca Faction) - 15 seats

- Fraksi Madagascar (Madagascar Faction) - 7 seats

[1] Similar to the China model, or the Shenzhen SEZ model, Nasution almost made that system in his presidency

[2] Guntur attempted to mimic Carter's healthcare policy, the golden egg for his hardcore PPI supporter and also possibly PPP's liberals.

[3] Different ideology, different propaganda, yet same purpose. Guntur will tell communist sympathizers unions in the Soviets or France as examples, while he would say the liberals that unions as in New Deal US labour Unions. Despite these unions may refer to opposite systems, the message stays similar.

[4] Australian Aggression Sukarno, where the proclamator bank to US-leaning.

[5] PPI was pissed, but nothing can be used as an attack as the coalition promise came from verbal promises, not written contracts.

[6] OTL Exxon CEO in the 90s

BIG explanation to give.

The old me gave general guidelines on each Indonesian era, giving a strict path. I felt this has been bland after a month's hiatus, so I spice things up (Sudarman's candidacy as one). However, I realised too that the past-me method can obstruct my creativity, it gave me a sense of dread and confusion, and thus no paragraphs were written. I was almost at loss about this TL, almost unable to continue (laziness might be one, but the most crucial was the indecisiveness within me because I thought so many have to change). Nevertheless, I promised myself, so I need solutions fast. I eventually take a break (looking at other TL inspirations, both here and SV, found many luckily). I also looked at a few papers regarding Indonesian history. But the best turn of events came from an initiative to build up other parts of this TL, most notably ATL USA. I recalculated the EV (very fun actually), constructing TL-wise until 2024 (long, but also reinvigorating me in a way) and eventually gave broad guidelines so future me might detail it further. I ended up finishing this post just this morning, finally returning a willingness to move on. I have considered that, although this TL should be Indonesia-centered, the world is never centred around Indonesia, but can be so among major players on the global stage. This time, I used the US as the "constant" of world trends, giving me a sense of direction in Indonesia while maintaining the fluidity of Indonesian politics. This may contribute to my unusual interest in US politics, but basically, it makes room for TL construction.

[4] Australian Aggression Sukarno, where the proclamator bank to US-leaning.

[5] PPI was pissed, but nothing can be used as an attack as the coalition promise came from verbal promises, not written contracts.

[6] OTL Exxon CEO in the 90s

BIG explanation to give.

The old me gave general guidelines on each Indonesian era, giving a strict path. I felt this has been bland after a month's hiatus, so I spice things up (Sudarman's candidacy as one). However, I realised too that the past-me method can obstruct my creativity, it gave me a sense of dread and confusion, and thus no paragraphs were written. I was almost at loss about this TL, almost unable to continue (laziness might be one, but the most crucial was the indecisiveness within me because I thought so many have to change). Nevertheless, I promised myself, so I need solutions fast. I eventually take a break (looking at other TL inspirations, both here and SV, found many luckily). I also looked at a few papers regarding Indonesian history. But the best turn of events came from an initiative to build up other parts of this TL, most notably ATL USA. I recalculated the EV (very fun actually), constructing TL-wise until 2024 (long, but also reinvigorating me in a way) and eventually gave broad guidelines so future me might detail it further. I ended up finishing this post just this morning, finally returning a willingness to move on. I have considered that, although this TL should be Indonesia-centered, the world is never centred around Indonesia, but can be so among major players on the global stage. This time, I used the US as the "constant" of world trends, giving me a sense of direction in Indonesia while maintaining the fluidity of Indonesian politics. This may contribute to my unusual interest in US politics, but basically, it makes room for TL construction.

That big excel at the bottom has all the vote percentage of each US presidential election until 2024. I made this final, and I will unravel this one by one. (1988 one probably next two parts)

A long story short, I have summarized US events all until 2024 (Big Events, Presidents*, even factions in power), way enough room for world-building. I freed myself to give any future Indonesian events to let me just go with the flow. Fortunately for you guys, I am prepared to unleash more lore.

Alright, enough with the little introspection. Legislative elections are over, next is Presidential debates, the new Parliament, and all of its political shenanigans.

See you next week.

*Don't worry, my promise that there would only be one more OTL US president in TTL US President still holds true. Actually, I may have given the hint far before in one post, try looking for it

Last edited:

"Nothing can possibly go wrong"Indonesia was again the exclusive beneficiary of Japan’s economic miracle

-General Susilo Sudarman-

Thanks for the input yall, appreciate it. Oh, I forgot about the other two terms newly introduced here. I'm fairly certain my readers would have some Indonesian backgrounds, but I still have to appeal non-Indonesian readers.

"Teruskan" in Teruskan Coalition means continue or proceed. In 2009 OTL, President SBY used Lanjutkan as their campaign slogan. Lanjutkan and Teruskan are synonyms, both claims the continuation of incumbency.Teruskan Coalition

This word was the ITTL slank version of "partake". It is an OTL Indonesian slank word too. You can relate "nebeng" as the activity in Lyft share rides, a perfect analogy."Nebeng-ism"

21.8. Race of 1988: The Debates

Two Parted Ways

The 1988 legislative election ended with two parties emerging triumphant in the year of confusion. Domestic factors have been voters’ actual concern, recalling the worrying events before this election. Foreign events had been a distant hum for Indonesians, even with South Vietnam’s news broadcasted daily. The constituents also desired a change of direction, as three decades of pro-liberal inclinations (Nasution’s apathy to any policies outside infrastructure efforts and LKY’s lengthy premiership) have drained the common populace. It seemed, arbitrarily, they discovered two alternatives.

Partai Pekerja Indonesia won over Guntur’s charisma, the son of the founding father himself. Senior communist politicians rooted in decades of political activism, like Njono Prawiro and juniors of Aidit rule, have noticed pro-Guntur politicians elected in 1988. These politicians have endorsed communist policies throughout their lives, especially after the Soviet Union’s resurgence from the new leader. Price control, equal income and state property had been their fundamental promises throughout the birth of Indonesian communism. They supported state-controlled industry, banks, and finance. For any stereotypical communist one encounters, these politicians were perfect replicas. Guntur’s ideology, meanwhile, preferred the American version of the welfare state. They respect liberty, individualism, and private property. Their primary directive was the enlargement of trade unions, respectable minimal wages, a progressive tax system, and redistribution of income through government programs. These two drifted further apart after pro-Guntur politicians gave no emphasis on a strong unitary state, but a collective federation of union workers coalesced as one government’s interest groups. Old communist politicians dictated that the state need not have unions because those workers controlled the state. Also, Guntur's defence policy differed by advocating a robust military, while communist politicians preferred all citizens armed for the revolution. [1]

The 1988 legislative election ended with two parties emerging triumphant in the year of confusion. Domestic factors have been voters’ actual concern, recalling the worrying events before this election. Foreign events had been a distant hum for Indonesians, even with South Vietnam’s news broadcasted daily. The constituents also desired a change of direction, as three decades of pro-liberal inclinations (Nasution’s apathy to any policies outside infrastructure efforts and LKY’s lengthy premiership) have drained the common populace. It seemed, arbitrarily, they discovered two alternatives.

Partai Pekerja Indonesia won over Guntur’s charisma, the son of the founding father himself. Senior communist politicians rooted in decades of political activism, like Njono Prawiro and juniors of Aidit rule, have noticed pro-Guntur politicians elected in 1988. These politicians have endorsed communist policies throughout their lives, especially after the Soviet Union’s resurgence from the new leader. Price control, equal income and state property had been their fundamental promises throughout the birth of Indonesian communism. They supported state-controlled industry, banks, and finance. For any stereotypical communist one encounters, these politicians were perfect replicas. Guntur’s ideology, meanwhile, preferred the American version of the welfare state. They respect liberty, individualism, and private property. Their primary directive was the enlargement of trade unions, respectable minimal wages, a progressive tax system, and redistribution of income through government programs. These two drifted further apart after pro-Guntur politicians gave no emphasis on a strong unitary state, but a collective federation of union workers coalesced as one government’s interest groups. Old communist politicians dictated that the state need not have unions because those workers controlled the state. Also, Guntur's defence policy differed by advocating a robust military, while communist politicians preferred all citizens armed for the revolution. [1]

Ironically, they adopted US pro-union propaganda as their own, as an example of this poster would be translated as PPI propaganda.

This branch of PPI, eventually named Gunturism, was a synthetic balance of communist sympathies with a Western outlook. A bridge between two ideologies, moderate if one shall refer. It was a decent fuse of ideas for both PPP’s Barisan Progresif and PNI-R’s Nusantara to show support. Young Barisan Progresif supporters respected Guntur’s support of Carterism while Nusantara appealed to Guntur’s defence policy. Ali Sadikin, the leader of the Nusantara faction, also flirted with Guntur’s wealth-redistribution policy. Even so, PNI-R and PPP’s Barisan Progresif still doubted Guntur’s commitment to pro-West views as the party had been entrenched with anti-US partisans. [2] Gunturism displayed a significant challenge for gaining coalition partners; none of the other parties (albeit leaning) wished for mutual pacts.

As PPI won by charisma, Partai Umat Islam won by the political ambience. Since the decades of Pancasila-ism fervently campaigned by the previous three assertive predecessors (Sukarno, Nasution and LKY), many disenfranchised underachievers of the new government system felt an urge for a new direction. Consists of the rural farmers who failed to rise as quickly as their urban counterparts, natives everywhere envious of outsider’s success and religious intellectuals vying for spiritual rejuvenation, these ‘losers’ of the old system demand change that only PUI provide. Gusdur and Amien Rais are towering figures in Indonesian Islamism. It received good sentiment from highly religious population groups (Minang and Mojokerto as examples). They gave Islam a presence in Indonesia’s governance, vital for fervent adherents who challenge the regime's reluctance on this matter. The conservative revival of these places gave PUI the starlight of the 1988 election. PPP’s Kesejahteraan Rakyat also rose from mere 30 people before the split, to 121 congressman, outnumbering Barisan Progresif. [3]

Gusdur during a visit, 1988

Promising signs for the incumbent Teruskan Coalition came from the active participation of the PUI’s top officials in the governing process. While Mahathir Mohammad was prevalent, his policies were unorthodox even to common Indonesian natives. PUI would become the catalyst of this extremist wing, eventually mustering a performing coalition with favourable support. Words of Mahathir Mohammad to step down for a compromise candidate are conversed by Teruskan party officials. The June and July Riots have influenced significantly towards PPP’s decrease in party seats. Daim Zainuddin, General Susilo Sudarman, Mahathir Mohammad, Abdurrahman Wahid and Amien Rais have held an unofficial meet in Sudarman’s house at Setiabudi, Jakarta. It was a long discussion, notably from the press’s presence on Sudarman’s front gates for almost 7 hours. On the 20th of April 1988, the Teruskan Coalition held a press conference for the new Premier.

On behalf of the two partners of this great coalition, we should tolerate one another with a single goal of perfecting Indonesia as a better, fairer, and more devout nation. Our principles may aim for a single purpose, but policies would differ on one faction and another. To appease the common people, we should contribute to a unifying government, capable of reigning against seeds of discord and disorder. Fortunately, the elected coalition has given me confidence in the new government with Abdurrahman Wahid as my vice Premier. This rearrangement will satisfy the needs of the entire Indonesian as well as fulfilling our party’s main objectives. Our new administration shall sow the fruitful seeds of success and distribute them to everyone in need. It is time for a gentler, kinder era.

Mahathir Mohammad

Mahathir and his wife were photoed after the declaration

The premier continued his dominance on the federal podium, possibly to cater for the possibility of Kesejahteraan Rakyat’s policies enacted along the term. Also, being the largest part of Teruskan, PPP must commit to leading after a devastating riot after their actions. For now, the government is safely PPP. [4]

The Debates

Gusdur, Alwi Shihab and Habibie were conversing before the 1988 debate, on the right is Yenni Wahid, Gus Dur's daughter.

Besides the political drama, 1988 was the first presidential debate in Indonesian history. Previous versions of this head-to-head with all candidates almost happened in 1973, but it emerged more as a dialogue of presidents than a debate of policies. This time, it mimicked the US Presidential Debates. Furthermore, additional features on cable companies’ equipment had been arranged for the two candidates. TVNI, the state television, sponsored the debate, coming in as the de-facto political cable of Indonesia. Government mandate had allowed these debates to be broadcasted on every Indonesian station, hoping for higher coverage.

There would be three debates that occurred during the 1988 election. June 9th was the first of the bunch covering government legitimacy, law and Constitution, and Indonesian democracy. This is related to the recent events in Jakarta and Timor, both suffered great strides in riots along the way. Likewise, government legitimacy came into question with the Constitution’s failure to determine the limits of various government hierarchies. It was not a major crisis for most Indonesians at the time, but it was brought deliberately by the TV cables. This happened because cable regulations got problematized with local, royal, and state republic bureaucrats. [5] From 1945, 1950, 1959 and 1973, the revised Constitutions have been a temporary settlement to the issues at hand, one after another. The last establishment, 1973, was written to solve the constitutional crisis that erupted by the justification of Madagascar, Malaya, and Papua into an integral part of Indonesian society. That has given fundamental bases to operate, but there were further questions. Finally, the first debate challenged candidates to define “Indonesian democracy” with implementations on fulfilling the ideal course of action.

The adult audience (especially government-related workers) sensed a US-based debate system would work poorly in Indonesian settings. Expectations for the first presidential debate were apathetic. However, this debate marked an excellent instrument of presidential campaigns, one that favoured extensively a charismatic candidate. The first presidential debate happened in the ballroom of Hotel Indonesia, just across from the Mandarin Hotel where the infamous June riots had occurred.

Alwi Shihab moderated the first debate regarding government legitimacy. From the two candidates, it seemed both figures have evolved as their exaggerated labels. For starters, General Sudarman evaded any strong opinions about the recent events by claiming them as tragedies. If not, the General had deflected any moderator’s attempts to relate the question even further. Much to the general’s stubbornness, he even countered the moderator with severe accusations of manipulative media. Guntur, as expected, hammered the general by accusing Sudarman of siding too much with Mahathir and his cronies. He highlighted previous riots had been detrimental to everyone. Guntur’s attacks may harm his core bases, but they envigorated Barisan Progresif devotees.

Alwi Shihab then opened another topic regarding Indonesia’s legitimacy on the international stage. General Sudarman cited Indonesia’s foreign policy problem from various scholars, concluding Indonesia must adhere to neutrality and pacifism. He refused to increase the military, relying on the international world to be more peaceful as time advanced. Guntur, again, attacked Sudarman, citing the new aggression in the Soviet Union, decrying peace through strength as Indonesia’s better foreign policy. This upset hardcore Barisan Progresif, but PNI-R was elated with Guntur’s strong viewpoint on defence. About South Vietnam, Guntur underlined Indonesian ties to South Vietnam while Sudarman merely expressed the horrors of the Vietnam War. Finally, regarding separatism in Aceh, parts of Maluku, Papua, and East Timor, Sudarman exclaimed the key to diplomacy while Guntur heavily defended Indonesia’s idea of a nation.

Guntur won the first debate from multiple fronts, both in character and political circumstances. Before the second debate began, rumours of the Viet Cong completely collapsed had arrived in the Indonesian public, giving the necessary boost to ties with South Vietnam. [6] Moreover, East Timor had grown into a mild protest regarding Mahathir’s actions in Dilli, thus exhausting Sudarman’s campaign even more. Aceh had not helped with further demands of pro-Islam autonomy in the region. All these events gave Guntur increasing supporters.

The second presidential debate (law and Constitution) became another heated argument because of the recent rise of localism across Indonesia. The 1973 Constitution repetitiously failed on tackling the modern crisis of the Indonesian federal government regarding government structure, autonomy and rights that have become increasingly apparent from the eve of the Labour Crisis. [8] The debate transpired in Borobudur Hotel with increasing media presence comparing the first one.

Unlike the previous debate session, Sudarman turned aggressive on the series of questions inquired about the Constitution. He vowed to protest the Constitution and deny any changes as he argued laws are not interchangeable as men are. However, he gaffed himself that Indonesians should reeducate themselves about the Constitution, the output received as insulting for many. Guntur, after this event, confronted Sudarman from his statements, claiming that the 1973 Constitution was made in desperate times to negotiate with new republics. As Indonesia became more integrated, he implied essential changes should aim for an everlasting federation. Still, his momentum ended when he supported a split of Indonesia into numerous states - a motion DEI-Indonesians deeply rejected because of their trauma with a particular Dutch encounter. [7]

Fortunately, Guntur won the debate with topics about law, deciding that a federal government must have a baseline of law all autonomous states must obey while local governments would be given adequate autonomy in matters local bodies could handle. He cited that three nations (the US, Soviet Union, and Federal Germany), all major world players, constitute a degree of federalism. In this debate, he reaffirmed his communist base that central government is not admirable in this modern era. PPI's communist appeal seemed to weaken Guntur, but that checked Sudarman’s capacity to express anything passionate about law.

The third debate, Indonesian democracy, tested presidential candidates about an abstract notion of Indonesia’s democracy that differs from mainstream democracies. This growing concern from current Indonesian governments attempting to replicate American democracy became an issue for Indonesian intellectuals. As expected, Subandrio acclaimed his support of Sukarno’s idea of democracy as the deliberative consensus of all communities. He repeated the fourth clause of Pancasila as his guiding principle, one that harnessed decent support. His ideal solution to fulfil Indonesia’s unique democracy was to let time pass on, as Indonesians would be more developed than in their past, allowing maturity as the endgame. Guntur, similarly, had spoken close arguments that mirror Subandrio’s. Though, he preferred Indonesia's democracy as dialectics between various opposing powers whose ideas represented contrasting approaches to progression. Then, he trusted the civilians have good faith in deciding the best path forward.

The first presidential debates were not outstanding due to the seemingly narrow discussions it has conveyed. Still, it became the precursor of Indonesian history of further presidential debates with better effects on Indonesia’s aptitude of choosing. National scholars have chosen this event as consequential to Indonesian history. In the subsequent months, it boosted Guntur’s popularity. In the succeeding times, it gave many changes for competent policymakers to have a better stance, especially after the 2010s.

[1] Senior PPI politicians are hardcore Marxists while Gunturism became more of a 'social democracy with Indonesian characteristics'.

[2] Njono Prawiro and Aidit-ism still influence PPI. Remember that Guntur came and just control the party. This is OTL Partai Demokrat and SBY in the early years.

[3] Expect more on 1990s political shenanigans

[4] Emil Salim, the Barisan Progressive leader, also showed up as signs of 'unity', whatever that is for the 1988 PPP.

[5] Sneak peek at what's to come.

[6] I mention Vietnam as the 'only' foreign event to appear in the debates. This was not the case, as further chapters will explain. However, Vietnam was the only one that affected the debate.

[7] Republik Indonesia Serikat is a painful remembrance of the Dutch 1st and 2nd Aggression. A federation has been a decent trend, but taking this plan would make things go too far. We wouldn't want a backlash of that to happen.

[8] Again, another sneak peek.

So, ITTL Indonesia has been significantly better in the democratization of the populace. Just a "feeling good" chapter while still addressing portions of the 1988 drama. The next post should be the presidential results before we close the chapter with foreign election results (especially the US).

We have an incumbent under a pleasing position (good economy, 'peaceful times') and a challenger with oratory skills far beyond the incumbent. Who do you think will win?

Before I finish. Here is the map of the 1988 legislative election.

(Red = PPI [Partai Pekerja Indonesia] , Blue = PNI-R [Partai Nasional Indonesia - Raya], Green = PUI [Partai Umat Islam], Yellow = PRD [Partai Rakyat Demokratik], Golden Yellow = PPP [Partai Persatuan Pembangunan], Light Blue = BKDT [Barisan Koalisi Daerah Timur], Purple = Partai Melanesia, Black = PMPM [Partai Majelis Persatuan Muslimin])

Last edited:

I can only say the 2010s will be tumultuous.Terrorism?

21.9. Race of 1988: Hear Ye the Word of the People

Call for Extension

The Resurrection of Nusantara: How Indonesia Rose from Ashes of Colonialism (2015)

Chapter 4: Post-LKY Populism

Two months was all that separated the two pivoting elections of 1988. With the legislative chamber won by the incumbency, PPP officials would do their best to maintain the presidency. The task was not straightforward, Guntur Sukarnoputra had been accumulating voters in all corners of Indonesia. Meanwhile, international events provided benefits to Sudarman and the incumbent government. Methods of keeping the impetus were compulsory.

Sudarman’s caution in the presidential debates had harmed his candidacy with polling decreased to margins below 5% of the popular vote. This was also caused by Guntur who had blared his speeches passionately, impacting both the youth and the elderly. The youth, naturally, have tended to vote for inspirational candidates that favoured a change in any form. The elderly, meanwhile, have noticed Guntur’s resemblance to his late father, placating him as the true Sukarno successor. Still, voting tendencies were distinguished not in generation, but the territory. To comprehend the process of voting groups between the two candidates, their campaign promises had been the perfect approach.

Ostensibly, Sudarman’s appeal was the continuation of the successes within Subandrio’s presidency. That meant all Indonesians that gained from Subandrio’s (mostly LKY’s) policies supported Sudarman. Yet, Sudarman’s popularity was slightly damaged by his Premier, Mahathir Mohammad, for whom his initial government policies were still too radical for his promises of perpetuity. After he was appointed the Premier of Indonesia, Mahathir Mohammad reaffirmed his promise to his core ideals. He believed that Indonesia had given few elites golden opportunities for abuse of wealth, aiming for the lowest of farmers and labourers for better equality. He was steadfast in support of wealth redistribution, especially from the urban cities to rural villages, claiming that this method is the quickest way to eliminate inequality. There had been allegations of his inauguration speech as “dog-whistling” towards ethnic Chinese as the economical advantage societies in the 80s boom. But many Kesejahteraan Rakyat politicians object to these rumours, preventing mainly pro-ethnic Chinese Barisan Progresif from leaving the party. Eventually, these Kesejahteraan Rakyat officials targeted Javanese as their adversaries, bringing the old rhetoric that won Subandrio against Nasution. Another tactic Sudarman's campaigners used was their success in ending the Labour Crisis, a good one as workers were delighted by the outcome.

This attack succeeded in Nasution’s downfall, but it gave a minuscule blow to the Guntur campaign which advocated everything their tactics had aimed for. Guntur, akin to Sukarno, had a broader appeal to almost everyone, rural and urban. Sudarman’s appeasement of native Indonesians falls flat on Guntur’s charisma ubiquitously. The elitist Javanese indictment also fell flat with most workers and farmers constituting Guntur’s core base, with the PPI manifesto unconcerned on any type of ethnicity. However, Guntur’s strong support can be derived from mostly Javanese as PPI’s core communist supporters came from the Northern coasts of Banyumas State, predominantly Javanese. There had been hoping for PPI’s clan that minorities will vote for Guntur as communists rarely favour racism as public policy. Furthermore, with China and India as communist states, Guntur would have a healthier appeal to low-class minorities with thick pro-ethnicity backgrounds. Still, with many Chinese and Indian Indonesians liberalized by LKY’s policies, political pundits had little idea whether they would defect to the PPP.

Mahathir’s ardent wish to implement many of his Kesejahteraan Rakyat policies contradicted LKY’s policies in many forms. Federal governments encouraged positive discrimination for equality, which of course harmed Chinese Indonesians and other minorities labelled as “economically privileged”. Political experts suggested Mahathir’s impatience originated from his think-tank’s prediction of a drastic increase in wealth inequality in the 80s, with the 90s as the tipping point for wild conflict in Indonesia. These think tanks pointed to specific ethnicities as the culprit of the wealth inequality, Mahathir intended to balance this with a nativism-leaning stance for business regulations and other economic policies. The first example was the Program Rekonsiliasi, a bureaucratic program aimed at boosting local native businesses with minorities aiding them as “learners” and “co-sponsors”. These affluent conglomerates should give various aid, in money or vocational training, to newcomers so businesses may diversify and flourish. Barisan Progresif, Singaporeans in particular, condemned this as biased against Chinese minorities famous as productive businessmen. Luckily, this policy garnered great support from native Indonesians, noted many members of PUI, PRD and PNI-R supported it.