2 CA's or a full sized BC is a better escortAm still curious, given the case in the 30s, how expensive would be to have this panzershiffe style armored/ heavy cruiser of carriers escorts?. Of course this proposed design should have all possible technical advances applied to it, e.g. a better main gun loading system.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dread Nought but the Fury of the Seas

- Thread starter sts-200

- Start date

Not really, CMBs had plenty of use off the Belgian coast, but the designs were much as OTL.Will we be seeing any updates regarding Coastal Motor Boats . Any changes in their development ? Has changes in aviation impacted on available engines or is it too early to see much of s change ?

Aero engines are likely to be a little behind reality at this point, simply as the war ended early and development consequently slowed down.

However, civil aviation, racing and ongoing military development are still going to be drivers.

I can't find the graph but someone posted a chart of top aircraft speeds in OTL and one of the impacts of WW1 was to retard the upward line of ever increasing aircraft speed as the emphasis switched to agility for dogfighting. With an earlier end to WW1 the emphasis will presumably switch back to speed rather than manoeuvrability earlier meaning that in ATL 1925 aircraft might be slightly faster than OTL.

I can't find the graph but someone posted a chart of top aircraft speeds in OTL and one of the impacts of WW1 was to retard the upward line of ever increasing aircraft speed as the emphasis switched to agility for dogfighting. With an earlier end to WW1 the emphasis will presumably switch back to speed rather than manoeuvrability earlier meaning that in ATL 1925 aircraft might be slightly faster than OTL.

I don't think it would, assuming the air war proceeded along similar lines to OTL the events that lead to the development of the first air superiority fighters and the tactics they employed would have taken place anyway by the end of TTL's war. Bloody April, the rampage of the Red Baron and his squadron and the introduction of the Sopwith Camel all occured in 1917 and the new fighters that would take to the air for the spring offensive and the closing battles of 1918 were all either on the drawing board and in production by the end of the war in TTL.

A County class cruiser cost about £2.5M, a New Orleans class about $14M.Am still curious, given the case in the 30s, how expensive would be to have this panzershiffe style armored/ heavy cruiser of carriers escorts?. Of course this proposed design should have all possible technical advances applied to it, e.g. a better main gun loading system.

Roughly speaking a 12", 18,000t cruiser would therefore be £4M / $25M

Trouble is why would you want to build such a ship as a carrier escort if you could have a decent capital ship instead ?

Big cruisers were used as carrier escorts, but that wasn't out of choice.

I can't find the graph but someone posted a chart of top aircraft speeds in OTL and one of the impacts of WW1 was to retard the upward line of ever increasing aircraft speed as the emphasis switched to agility for dogfighting. With an earlier end to WW1 the emphasis will presumably switch back to speed rather than manoeuvrability earlier meaning that in ATL 1925 aircraft might be slightly faster than OTL.

I don't think it would, assuming the air war proceeded along similar lines to OTL the events that lead to the development of the first air superiority fighters and the tactics they employed would have taken place anyway by the end of TTL's war. Bloody April, the rampage of the Red Baron and his squadron and the introduction of the Sopwith Camel all occured in 1917 and the new fighters that would take to the air for the spring offensive and the closing battles of 1918 were all either on the drawing board and in production by the end of the war in TTL.

Tricky debate that. I'm sure speeds stopped increasing partly due to people started putting a lot more weight on aircraft (guns, bombs) than on pre-war 'racers'.

Post-war, that racing development would resume.

As Sciox suggests, the air war of the story proceeded much as reality.

Perhaps just as important, the development of engines will have been affected. Two of the most relevant to post-war aviation/racing, the Lion and the Liberty, would be far less advanced towards production than in OTL due to the early end of the war.

I don't think the Royal Navy could get 12" guns on 18,000 tons with the kind of speed, range, and armor they wanted. Their 10" studies hit 19,000 tons and refused to budge down.A County class cruiser cost about £2.5M, a New Orleans class about $14M.

Roughly speaking a 12", 18,000t cruiser would therefore be £4M / $25M

Trouble is why would you want to build such a ship as a carrier escort if you could have a decent capital ship instead ?

Big cruisers were used as carrier escorts, but that wasn't out of choice.

Going back to my earlier point about what the UK should have done with its 13.5" guns as the treaties retired them from ship born use I'd say that Malta in particular really could have used around half a dozen as it would have effectively eliminated any chance of taking Malta by amphibious assault and probably from anything but starvation

If all you're building a cruiser for is carrier escort, you want something like OTL's Atlantas - lots of DP guns in fast-loading, power-operated mounts and the best fire-control you can put on it. Heavy guns and/or armour are a waste because you never plan to be in gun range of an enemy warship. Yes, in OTL fast BBs, BCs & CAs drew carrier escort duty because they were there, they were fast and they carried a lot of AA, but a dedicated escort ship can do the same job much more efficiently.Am still curious, given the case in the 30s, how expensive would be to have this panzershiffe style armored/ heavy cruiser of carriers escorts?. Of course this proposed design should have all possible technical advances applied to it, e.g. a better main gun loading system.

In a 1920s context, a "carrier escort" probably means something to deal with fast CLs/DDs that are trying to get into gun/torpedo range of your carrier. That implies something like OTL's 'E' class - fast, lots of 6" QF and enough armour that it doesn't get mission-killed by a lucky hit from a destroyer.

This is incorrect. In the 1920s the big worry was a scout cruiser stumbling onto your carrier, a worry that US Navy exercises showed was not an unfounded one in the interwar period. Fleet Problem IX saw Saratoga spotted by surface ships before she could launcher strike against the Panama canal, and in Fleet Problem XVII she was 'sunk' by opposing battlecruisers.If all you're building a cruiser for is carrier escort, you want something like OTL's Atlantas - lots of DP guns in fast-loading, power-operated mounts and the best fire-control you can put on it. Heavy guns and/or armour are a waste because you never plan to be in gun range of an enemy warship. Yes, in OTL fast BBs, BCs & CAs drew carrier escort duty because they were there, they were fast and they carried a lot of AA, but a dedicated escort ship can do the same job much more efficiently.

In a 1920s context, a "carrier escort" probably means something to deal with fast CLs/DDs that are trying to get into gun/torpedo range of your carrier. That implies something like OTL's 'E' class - fast, lots of 6" QF and enough armour that it doesn't get mission-killed by a lucky hit from a destroyer.

So in this context, and in actual practice, your carrier escort is whatever scout cruisers you can spare for the task. For the Royal Navy the E class would indeed be good candidates; the US Navy would and did use their 8" scout cruisers.

True enough - to some degree I picked a random number there, I suppose a 1920s Invincible equivalent.I don't think the Royal Navy could get 12" guns on 18,000 tons with the kind of speed, range, and armor they wanted. Their 10" studies hit 19,000 tons and refused to budge down.

(although why anyone would want such a thing is very much the point...)

As a fan of a turreted E-class, I am very interested in this updateall four of them.

Hard Graft and Enterprise

Hard Graft and Enterprise

In September 1918, four new light cruisers were ordered by the Royal Navy, although it would be nearly another year before the last of them was laid down.

The ‘E-class’ had originally been dreamed up during the war to counter the supposed threat of fast German cruisers. In fact, the Germans never built any such ships, but the design prepared by the DNC attracted considerable interest at the top of the Navy. Their latest battlecruisers could achieve speeds of over 31 knots, but at the time no RN cruiser was capable of more than 29 knots.

The need for faster cruisers had also been highlighted by the wartime sharing of information with the United States. Their new ‘Omaha’ class would (at least on paper) be capable of 34 knots, and Britain therefore needed an answer. The Omahas used casemated guns, which the British designers considered old fashioned, however they were powerfully armed with ten 6” guns, and were capable of firing at least five of them in any direction.

The Admiralty therefore succeeded in exempting the E-class from the general culling of orders for new ships that took place at the end of the war, and they later received an unexpected bonus. Originally, three ships were planned, but an order for one of the ‘D-class’ cruisers was found to be expensive to cancel, and the Sea Lords successfully lobbied for the contract to be reused to produce a fourth E-class.

Wartime designs for the E-class used conventional single shielded mounts for seven 6” guns, but experience of war showed the limits of these mounts, and the Admiralty wanted a better distribution of armament than was offered by five centreline and two wing guns.

The length of the ships didn’t change, but the internal layout did, while an extra foot of beam allowed for a new armament. The forward boiler room was rearranged from fore-aft to side-by-side, and this allowed the bridge to be moved aft. An ammunition space was moved amidships from in front of the engine rooms to behind the aft boiler room, bringing the three funnels closer together and creating more room aft.

The armament layout became reminiscent of the ‘Lion’ class battlecruisers, with two superfiring mounts forward, and the aft two mounts separated by the superstructure. Unlike the Lions, there was no engine and boiler room in between, but topweight and hull space considerations prevented the installation of superfiring mounts aft, while the position of Q-mount allowed another innovation; there was room for an aircraft launching ramp to be fitted behind it.

The mounts themselves were changed, with eight 6” Mk.XII guns carried in four twin ‘enclosed mounts’. Wartime experience had shown that crews in gunshields (particularly those that did not extend down to the deck) were very vulnerable. It was impractical to modify the hull design to fit proper through-deck turrets, but each of the new twin mounts carried 1” splinter plating at the front, roof and sides, which stretched back to provide protection for the loaders and handlers. To save weight, the back of the mounts was open, but even so, they proved too heavy for manual working and were fitted with electric assistance during construction.

In service, the mounts continued to disappoint, as hoist and pass-up arrangements for ammunition limited firing to no more than 4 rounds/gun/minute after the first few salvoes. Although no worse than many earlier cruisers, the expected improvements did not materialise.

Despite being somewhat oddly arranged, with some pairs of boilers side-by-side and others fore-aft, the machinery was more advanced than any previous cruiser, as it was based on the latest ‘Admiralty V-class’ destroyer leaders. Four shafts delivered 80,000shp, with steam provided by eight boilers. The arrangement weighed just 1,590 tons, providing over 50shp/ton, in comparison to the machinery of the last C-class cruisers, which delivered 44shp/ton, while the earlier ships had been less than 40.

Displacement was just under 8,000 tons normal, or 9,800 tons at full load.

On trials in 1922, HMS Euralyus achieved 33.55 knots on the mile with 81,100shp at 8,620 tons, and both Enterprise and Emerald made over 33¼ knots.

In service, they proved to be fast and seaworthy ships, partly due to their relatively large size, and partly thanks to the ‘knuckle’ that was formed by the flared bow and the plating up to the foc’sle deck.

However, the hastily adapted armament was never entirely satisfactory, and although reliable enough, the arrangement of the machinery was obviously in need of improvement. They were transitional ships, part-way between a wartime design, and the much-improved light cruisers that would be built some years later.

In September 1918, four new light cruisers were ordered by the Royal Navy, although it would be nearly another year before the last of them was laid down.

The ‘E-class’ had originally been dreamed up during the war to counter the supposed threat of fast German cruisers. In fact, the Germans never built any such ships, but the design prepared by the DNC attracted considerable interest at the top of the Navy. Their latest battlecruisers could achieve speeds of over 31 knots, but at the time no RN cruiser was capable of more than 29 knots.

The need for faster cruisers had also been highlighted by the wartime sharing of information with the United States. Their new ‘Omaha’ class would (at least on paper) be capable of 34 knots, and Britain therefore needed an answer. The Omahas used casemated guns, which the British designers considered old fashioned, however they were powerfully armed with ten 6” guns, and were capable of firing at least five of them in any direction.

The Admiralty therefore succeeded in exempting the E-class from the general culling of orders for new ships that took place at the end of the war, and they later received an unexpected bonus. Originally, three ships were planned, but an order for one of the ‘D-class’ cruisers was found to be expensive to cancel, and the Sea Lords successfully lobbied for the contract to be reused to produce a fourth E-class.

Wartime designs for the E-class used conventional single shielded mounts for seven 6” guns, but experience of war showed the limits of these mounts, and the Admiralty wanted a better distribution of armament than was offered by five centreline and two wing guns.

The length of the ships didn’t change, but the internal layout did, while an extra foot of beam allowed for a new armament. The forward boiler room was rearranged from fore-aft to side-by-side, and this allowed the bridge to be moved aft. An ammunition space was moved amidships from in front of the engine rooms to behind the aft boiler room, bringing the three funnels closer together and creating more room aft.

The armament layout became reminiscent of the ‘Lion’ class battlecruisers, with two superfiring mounts forward, and the aft two mounts separated by the superstructure. Unlike the Lions, there was no engine and boiler room in between, but topweight and hull space considerations prevented the installation of superfiring mounts aft, while the position of Q-mount allowed another innovation; there was room for an aircraft launching ramp to be fitted behind it.

The mounts themselves were changed, with eight 6” Mk.XII guns carried in four twin ‘enclosed mounts’. Wartime experience had shown that crews in gunshields (particularly those that did not extend down to the deck) were very vulnerable. It was impractical to modify the hull design to fit proper through-deck turrets, but each of the new twin mounts carried 1” splinter plating at the front, roof and sides, which stretched back to provide protection for the loaders and handlers. To save weight, the back of the mounts was open, but even so, they proved too heavy for manual working and were fitted with electric assistance during construction.

In service, the mounts continued to disappoint, as hoist and pass-up arrangements for ammunition limited firing to no more than 4 rounds/gun/minute after the first few salvoes. Although no worse than many earlier cruisers, the expected improvements did not materialise.

Despite being somewhat oddly arranged, with some pairs of boilers side-by-side and others fore-aft, the machinery was more advanced than any previous cruiser, as it was based on the latest ‘Admiralty V-class’ destroyer leaders. Four shafts delivered 80,000shp, with steam provided by eight boilers. The arrangement weighed just 1,590 tons, providing over 50shp/ton, in comparison to the machinery of the last C-class cruisers, which delivered 44shp/ton, while the earlier ships had been less than 40.

Displacement was just under 8,000 tons normal, or 9,800 tons at full load.

On trials in 1922, HMS Euralyus achieved 33.55 knots on the mile with 81,100shp at 8,620 tons, and both Enterprise and Emerald made over 33¼ knots.

In service, they proved to be fast and seaworthy ships, partly due to their relatively large size, and partly thanks to the ‘knuckle’ that was formed by the flared bow and the plating up to the foc’sle deck.

However, the hastily adapted armament was never entirely satisfactory, and although reliable enough, the arrangement of the machinery was obviously in need of improvement. They were transitional ships, part-way between a wartime design, and the much-improved light cruisers that would be built some years later.

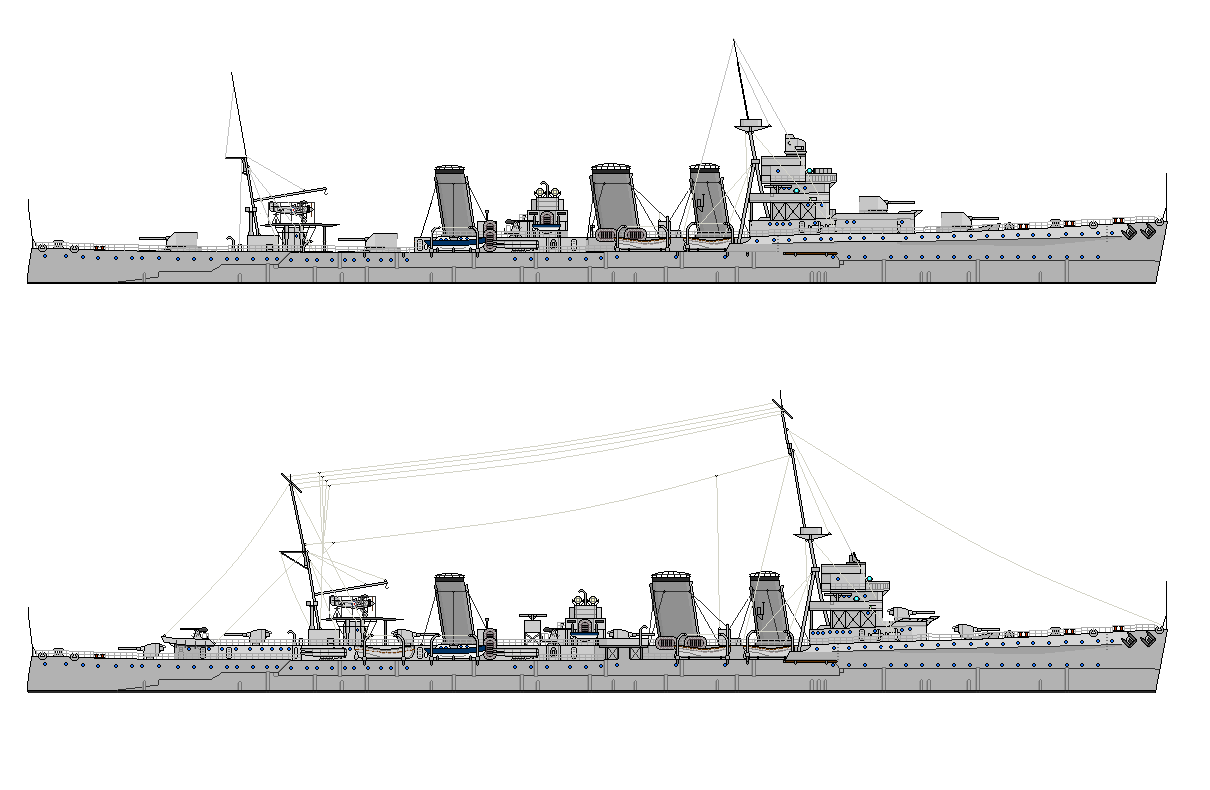

HMS Exmouth as originally designed with single mounts, and as she appeared after her 1925 refit with a prototype cruiser DCT.

Credit to Shipbucket for the original image.

Credit to Shipbucket for the original image.

Perhaps just as important, the development of engines will have been affected. Two of the most relevant to post-war aviation/racing, the Lion and the Liberty, would be far less advanced towards production than in OTL due to the early end of the war.

By the end of 1917 companies were tooling up to begin producing the Liberty, it was to power the planned American air fleet so most of the orders probably get cancelled before production can truly begin, another expense for Uncle Sam, but it probably still sees some success with the nascant American air corps and in the civilian sector, especially as companies will be keen to recoup their losses.

The Lion hasn't entered production yet, it's still in the handmade prototype stage, but it'll still be wanted for the next generation of British planes after the Camel and it probably still sees extensive post war use in military and civil applications like OTL.

Almost surprised the Brits didn't go for the Almirante Cervera layout, with singles in A and Y and twins in B, Q, and X. Guess they really wanted those enclosed mounts.The armament layout became reminiscent of the ‘Lion’ class battlecruisers, with two superfiring mounts forward, and the aft two mounts separated by the superstructure. Unlike the Lions, there was no engine and boiler room in between, but topweight and hull space considerations prevented the installation of superfiring mounts aft, while the position of Q-mount allowed another innovation; there was room for an aircraft launching ramp to be fitted behind it.

The mounts themselves were changed, with eight 6” Mk.XII guns carried in four twin ‘enclosed mounts’. Wartime experience had shown that crews in gunshields (particularly those that did not extend down to the deck) were very vulnerable. It was impractical to modify the hull design to fit proper through-deck turrets, but each of the new twin mounts carried 1” splinter plating at the front, roof and sides, which stretched back to provide protection for the loaders and handlers. To save weight, the back of the mounts was open, but even so, they proved too heavy for manual working and were fitted with electric assistance during construction.

Don't worry, I'm not killing off either of them - that could wipe out a whole generation of the fastest planes, cars and boats.By the end of 1917 companies were tooling up to begin producing the Liberty, it was to power the planned American air fleet so most of the orders probably get cancelled before production can truly begin, another expense for Uncle Sam, but it probably still sees some success with the nascant American air corps and in the civilian sector, especially as companies will be keen to recoup their losses.

The Lion hasn't entered production yet, it's still in the handmade prototype stage, but it'll still be wanted for the next generation of British planes after the Camel and it probably still sees extensive post war use in military and civil applications like OTL.

As you say though, with the cancellation, both are likely to be delayed.

I'm sure Phillip Watts would have suggested the Cervera layout, but given the casualty rates during the war on open mounts, they'd be keen on the 'improved' versions.Almost surprised the Brits didn't go for the Almirante Cervera layout, with singles in A and Y and twins in B, Q, and X. Guess they really wanted those enclosed mounts.

Not having a fifth mount also makes room for an aircraft platform and/or gives Q a wider arc of fire.

Still, there's room for further improvement.

That's interesting. Did US doctrine envisage using carriers in independent forces as early as the 1920s?In the 1920s the big worry was a scout cruiser stumbling onto your carrier, a worry that US Navy exercises showed was not an unfounded one in the interwar period. Fleet Problem IX saw Saratoga spotted by surface ships before she could launcher strike against the Panama canal, and in Fleet Problem XVII she was 'sunk' by opposing battlecruisers.

I'd assumed that the carriers would be accompanying the battle fleet, at least until the enemy was sighted.

Share: