You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dixie Forever: A Timeline

- Thread starter JJohnson

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 78 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 44: The Union and Confederates Enter the War Chapter 45: The War Comes to a Close Chapter 46: Winning the Peace if Possible Chapter 46.5: The Union and Confederate Progressives Chapter 47: The Roaring 20s! Chapter 48: Europe on the One Hand...and on the Other Hand Chapter 49: Asia's Progress Chapter 49.5: Confederate State Areas and FlagNazi Space Spy

Banned

I can't believe I have missed this fantastic timeline until now! Incredible work!

Lincoln can watch the election slip out of his hands OTL the taking of of Atlanta and the March to the sea sealed the election for him. TTL The distraction of the Arm of the Cumberland may be the final straw for the proverbial camel

Last edited:

Lincoln can watch the election slip out of his hands OTL the taking of of Atlanta and the March to the sea sealed the election for him. TTL The distraction of the Arm of the Cumberland may be the final straw for the proverbial camel

McClellan might win the election but Peace Democrats still need some luck getting clear majority in both houses.

Chapter 17: Atlanta Gets Personal (Part 3)

JJohnson

Banned

Aftermath (October 10)

"No dishonor in it sir," Johnson said as he led the general.

"What?"

"No dishonor in being captured, sir. It happens to a lot of soldiers," he added.

"Oh," Thomas replied. He'd kind of expected him to whoop and holler, but he'd been remarkably respectful and low-key about it. "I suppose you're right."

"Better than being dead, sir," Johnson said.

Thomas considered what his sisters and family would say, not to mention his reputation. "I don't know about that, sergeant."

**

As evening began to fall, the Confederates kept up the pressure, Hardee, Cleburne and Stewart keeping their troops going forward. Moving north on their horses, the generals saw their men advancing in barely a semblance of order. Cleburne noticed the absence of artillery fire. Most of the Union batteries had fallen to the Confederates, and most of their artillery crews must have pulled back across the creek.

As they approached, they happened upon General Thomas.

"That's General Thomas!" Hardee exclaimed. He trotted forward, followed by Cleburne.

"Is that you, William?" Thomas asked as the two men in gray approached.

"It is George," Hardee nodded. "Are you injured?"

"No," Thomas answered with a little sadness.

"My God, I never expected to take you prisoner," Hardee said.

Thomas sighed and gave a slight nod, but otherwise kept silent.

"Being a prisoner won't be so bad George. I spent some time as a prisoner of the Mexicans back in '46. Back in the good old days, huh?" Hardee said, trying to help his friend's mood.

Thomas's mouth did come to a slight smile at his friend's remembrance.

"May I present my fellow corps commander, General Patrick Cleburne," he said, gesturing to the man to his right.

"General Cleburne," Thomas nodded, with little enthusiasm. "I've heard a great deal about you. You're the man who got the Confederates to emancipate their slaves."

"I merely got the snowball rolling downhill, sir," Cleburne said with some modesty. "Any man will fight for his home state, regardless of color. It is an honor to meet you sir."

"I understand your corps broke my line."

"Yes sir, my men including our freedmen had that honor."

"A fine performance," Thomas said. His voice was flat, lacking any enthusiasm. It was understandable, given the circumstance.

"Thank you sir," Cleburne said, still being polite.

"Are my men treating you properly?" Hardee asked.

"Yes," Thomas answered. "This man is the soldier who captured me." He pointed to Sergeant Johnson. "He has been most gracious."

"What is your name, young man?" Hardee asked.

"Sergeant James David Johnson, 4th Georgia, sir," he answered smartly.

Cleburne recognized the man, seeing him during his weekly reviews of his brigades and divisions, for the past few months, ensuring the freedmen who'd been trickling in had been taken in and trained properly and treated well. Beside the sergeant, two privates, Darryl Polite and Robert Crane, both carrying a rifle and two flags themselves.

"You'll be noted in our dispatches for this, sergeant," Cleburne told him. "Few soldiers can say they captured the commanding officer of the opposing army."

"Thank you sir."

"George, you will be my guest at dinner this evening," Hardee said.

"Thank you, but I'm afraid I must decline."

"Don't be like that, George! We're old friends! We can swap old stories from back at West Point and in Mexico!"

"Please forgive me William. I don't mean you any disrespect. I simply cannot find it in my heard to celebrate even this reunion with an old friend when my army lies in ruins. I just suffered one of the worst defeats an army has experienced in the history of this continent," Thomas explained. "Besides, I do not wish to share a table with those who turned their backs on their country."

Hardee's face darkened. His friend's words stung. "Suit yourself, George. If we must be frank, I would rather not endure the company of a man who betrayed his state. Sergeant Johnson, please escort General Thomas to General Johnston's headquarters."

"Yes sir," he saluted. He tilted his head south, and Thomas walked on with Darryl and Robert joining them.

**

Elsewhere, as Sherman found the Army of Tennessee manning the defenses, reinforced not just by Georgia Militia, but around 20,000 black troops, a messenger ran to him.

"General Sherman, sir!"

"What? What is it?"

"We've been beaten sir! The rebels broke through Thomas's line at the center, and everything fell apart! The rebs have routed the Army of the Cumberland!"

"My God!" gasped McPherson

"It can't be true!" Sherman said gruffly.

"There's no doubt about it, sir! Several officers from the Army of the Cumberland arrived at headquarters in a panic! They say the rebels started attacking at one o'clock. Things went well at first, but then the division in the center just collapsed and rebels just poured in, and the line fell apart."

Sherman's mind was racing. The possibility for a true complete disaster was very real.

"Where is General Thomas?"

"No one knows sir. No word for several hours."

Sherman felt a stab to his heart at that. He tried to concentrate, shaking his head clear. If Thomas had been defeated, Johnston could strike north and capture the Union bridges along the Chattahoochee, trapping him and the remnants of Thomas's army on the south side of the river. He remembered Grant's warning about Jubal Early possibly coming down with 20,000 more troops. Could they have arrived?

"What's the situation?" he demanded.

"General Thomas is either dead or captured, sir. Hooker said he is taking command of the Army of the Cumberland and will try to withdraw to the north bank of Peachtree Creek as orderly as possible. He is urgently requesting reinforcements."

"Thomas dead?" Sherman said, stunned. Then the thought of Hooker at the head of the army, if only temporarily, filled him with dread. While the highest ranking commander there, Sherman thought him incompetent and a blowhard.

"Shall we attack sir?" asked McPherson.

Sherman's mind was spinning with all the what-ifs. "What?"

"Shall I attack, sir? If we attack, we may create a diversion which would enable the Army of the Cumberland to escape."

"No," he replied quickly. "No, an attack is out of the question. We need to get the Army of the Tennessee back to the north side of Atlanta quickly. Schofield too. If Thomas has been defeated, Johnston may try to follow up on that victory by capturing our army as they cross the river."

"Surely it can't be that bad, Cump. Perhaps Hooker can rally the men there and restore order and salvage the situation."

Sherman didn't reply, just shook his head.

"What do we do?" McPherson asked again.

"Message to Schofield," he said, turning to a courier. "Move his army at once to assist the Army of the Cumberland in crossing the river, while moving one division to Buckhead to prevent any rebel movements on our bridges. Wheeler's cavalry might be roaming about."

The courier saluted and left on his horse at a gallop.

Sherman turned to McPherson, "James, your army must march back too. I know your men are already tired, but they must march all night. We have to get them away from the east side of the city to avoid any possible traps the rebels might try to catch us in."

**

Cleburne took control of the situation, which calmed the Confederates, soothed their frayed nerves, and restored their confidence. He led the men across Collier's Bridge, after a good twenty minutes of fighting, holding it against the Yankees, as the bulk of the Yankee army was still on the south side. He had his staff officers get reinforcements to help hold the bridge, and had the men cut down trees on the north side to create a barricade on the south side of the bridge. He was a bit worried; he had maybe a thousand men on his side against the horde of Yankees coming his way, terror in their faces.

They fired, the Confederates unleashing their musket fire on the terrified opponents. Scores of Union troops fell, the wounded rapidly trampled under the boots of their comrades. Cleburne tried not to hear their screams. A formidable black horse carrying a Union officer emerged from the woods, trying to rally his men. His face was not one of fear, but rage...and determination.

"Form up men! I don't give a damn your regiment! Form up!" he yelled out. The frightened blue-coats rallied around him. "Now charge!"

The man and his horse sped forward. The Confederates fired furiously at them all. The Union officer was killed instantly. At this range, the Confederates couldn't miss. But the momentum of the enemy kept driving them forward. The Yankees tried the bridge, but that devolved into both muskets and bayonets. Even Cleburne felt a hit on his leg, stung by a bullet. Some of Cleburne's men instinctively stepped back from the line of fire to reload and pass muskets forward, maintaining some level of fire during the hand-to-hand.

He was struggling to reload, when he say his men left and right falling; fear began to take hold as he saw blue left and right across from him as far as he could see. Then he herd another sound...the Rebel Yell yipping behind them. The Yankees seemed to abandon the idea of taking the bridge, threw their weapons away and jumped down into the ravine. The drop of about 8-9 feet was a lot, but better that that than being shot or captured.

While reloading, Cleburne saw the most horrifying sight yet in his years of combat. The first few men who jumped ran to the other side, splashing in the waist-high creek. They struggled up the high and steep northern bank, gripping the exposed roots of trees and rocks to try to pull themselves up and out. As they did, more Union troops dropped down into the basin and grabbed the feet of the men above them, inadvertently pulling them back down into the basin. Only a few were able to pull themselves up the bank and run off to the north to safety. More and more troops were dropping into the basin trying to escape. Some even when unwillingly, knocked down into the ravine by the wave of men from the south side, many who were still firing back at the Confederates behind them.

Suddenly, something seemed to just click, and hundreds of the Union troops just dropped their rifles and seemed to decide their only chance of escape was the ravine. They jumped too. And suddenly the creek became a mass of blue-coated men, scrambling wildly for the other side of the bank and shouting in confusion. A few lucky men made it; most didn't. Crowded in, they got in each other's way, hindered their movements, and turned the creek into a mass of terrified men.

Finally, the Confederates came up on the other side. You can understand what happened next. After hours of fighting, most men reach a breaking point, and men don't question the morality of firing on defenseless men. Officers ordered the men to fire, and they just poured down their fire and fury on the men in the creek. Most had thrown their muskets away, so there was almost no return fire. Their screams were unlike anything Cleburne had heard at any point during the war. Not all the death was due to their bullets. In their rush to get across the north bank, many of the unlucky Union troops were shoved under the waist-high creek waters by the weight of their comrades. There they flailed about as the others ran over them, unthinkingly pinning them down under water till they stopped moved, drowned, or were crushed.

The south bank was in flames as the Confederates poured shot after shot into the mass. Cries of 'don't shoot!' 'we surrender!' went unheeded as Confederates shouted back "Keep firing!" and "Kill them all!"

Cleburne had seen combat do this to men. The nightmare that is battle and war could most certainly transform men into animals. Cleburne watched as the Yankees stopped trying to push over the bridge. The creek was crystal clear water yesterday; today it was red with blood. He wanted to shout to stop the carnage, but another voice told him every Yankee stopped here was one less person firing at him and his men on the battlefield tomorrow. War is most definitely hell.

He didn't know how long he watched, but the Confederates finally stopped their firing as the officers finally regained control of their men, and call for the Yankees to return to the south bank and surrender. Many did, and others continued trying to escape, using the piles of bodies of their dead comrades and protesting wounded as their stairs to ascend the steep bank and run north. As far as the eye could see, Peachtree Creek was clogged with the bodies of dead and wounded Union soldiers.

**

Johnston was meeting with his staff officers to get the report of the day while in the field on horseback. Artillery and muskets still fired off, but the sound was fading with the night, and Johnston was glad for that. Steward, Hardee, and Cleburne returned. The ground south of Peachtree Creek was so covered with Union dead you could walk two miles stepping from one corpse to the next and never touch the ground. It was Cleburne's breakthrough that turned the tide of battle decidedly in their favor. His use of tactics rather than just brute force is what did it.

By their reports, they had about 10,000 prisoners; killed around 8000 Union soldiers, captured 64 artillery, captured 48 battle-flags, and a large quantity of ammunition, small arms, and other supplies. The telegram he sent to Davis made the President very happy that night.

**

Sherman was riding the saddle slowly ahead of the others. He was nauseated and dizzy, and his thoughts were unfocused. His hands trembled. It was coming up to midnight, and with it the most disastrous day of his life was ending, and he was glad. He remembered the great battles of history - Saratoga, Hastings - would Peachtree Creek be added to that list? He remembered his early service in the war, when he had been essentially kicked out of the army under suspicion of insanity. His wife cared for him tenderly, but he had almost committed suicide. The demons that tormented him, he could feel them reaching out for him again, trying to pull him down into the darkness. He felt his mind going there. He closed his eyes, willing the demons away again.

What remained of the Army of the Cumberland was a shattered force maybe half its original size of 60,000. Many men were dead, wounded, or in no condition to fight. Many lost their weapons as well. Many division and brigade commanders had also been killed, captured, or wounded in addition to General Thomas. In many brigades, the highest ranking officers were now captains, according to his staff officers.

Until he could restore the Army of the Cumberland, he had just 40,000 men or so in McPherson and Schofield's armies. In terms of effective army size, it was now very possible Johnston outnumbered him.

McPherson and Schofield tried to persuade him to leave their armies on the south bank, while the Army of the Cumberland retreated to the north bank of the Chattahoochee to rest and refit, but he rebuffed them and told them they needed to avoid being trapped with a river at their backs. They advised it would be tougher to resume the offensive on Atlanta if they retreated. Sherman yelled back "Forget Atlanta! We have to look to the safety of our armies, not Atlanta!"

He calmed down, and reiterated that they needed to retreat to avoid risking another defeat, perhaps one greater than that Thomas experienced.

**

At the Niles house, men were celebrating, partaking in some liquor to celebrate and make toasts, as Johnston dismounted his horse.

"Where's General Thomas?" he asked.

"In your room, sir. We gave him dinner, and posted guards outside the door," said the officer nearest the general.

He climbed the steps to find General George Thomas sitting before an untouched plate of roast beef. As he saw Johnston, he stood up sharply and saluted.

"General Johnston," he said, his hand in a fine salute.

"General Thomas," Johnston said, returning the salute. He paused for a moment, before continuing, "I do hope I'm not disturbing your dinner."

"I'm sure you'll understand why I haven't much of an appetite. Besides, I doubt the other prisoners are eating this well."

"Your men are being treated properly, General. They are being fed the rations we captured during battle. I know you must be hungry. Please eat," he said, gesturing to the plate.

Thomas began eating slowly and reluctantly. Johnston continued.

"I want you to know we will do everything we can to make your captivity comfortable. It may be some time before you are released. If I'm not mistaken, the United States hold no Confederate officer of equivalent rank to yours, so prisoner exchange is a little more complicated."

"General Grant terminated prisoner exchanges some time ago, so it really makes no difference," Thomas said.

"Regrettable I must say," Johnston added. "Possibly inhumane, letting prisoners languish."

Thomas pulled his head up, "It was your so-called government's decision to treat captured black soldiers as if they were escaped slaves prompting his decision. If Forrest hadn't been encouraging desertions from amongst our ranks perhaps this could've been avoided."

"I can't say much regarding General Forrest, as I haven't worked closely with him," Johnston admitted.

Thomas just grunted again. He as upset, and Johnston really couldn't blame him. He'd be just as upset in Thomas's position. A servant brought Johnston plate for him after he sat down across from Thomas, and he began to eat.

"I have sent a telegram to our Department of War in Richmond asking as to your future circumstances. Since you are the highest-ranking officer we have yet captured, I am sure you will be accorded special consideration," Johnston said as he took a bite of his roast beef. It was delicious.

"No," his counterpart shook his head. "I want no special consideration apart from the same given my fellow soldiers."

"I will inform my government of your request," Johnston said in all politeness. "It does credit to your character. Given that you are a native Virginian they should be more likely to grant you that."

Thomas picked at his sweet potatoes and roast beef. Johnston walked over to grab some wine and poured a glass. "Would you drink a glass of wine with me, General? It has become more expensive due to the blockade, but it's not yet entirely unobtainable."

He poured two glasses before Thomas could respond, and set them down at the table.

"I might as well," Thomas finally said, picking at his food. "Today my army was destroyed. A glass of wine won't undo that, but I guess it won't hurt. As for those who believe I betrayed my state, well, I believe they betrayed their country."

"My country is Virginia," Johnston replied politely, as he took another bite. "The same was true of you once, as I recall. Our state was sovereign and independent as of 1783 and reserved its right to leave the Union if it so chose. If state cannot leave and is forced back in against its will, then its people are not truly free."

Thomas didn't answer the point, but continued, "You took an oath at West Point to protect the United States and the Constitution, yet you broke your oath, and instead became the servant of those radicals who tore our country apart for fear of Lincoln harming their interest in slavery."

"One could say the same of the radicals from New England who formed the Republican party broke the trust when they funded the terrorist John Brown to murder southerners in Kansas and Harpers Ferry, trying to foment slave revolts and widespread murder, and continued insulting the south for the last 30 years, calling us all manner of abominations for engaging in the same thing New England started in 1637. I myself own no slaves; neither does General Lee. General Forrest freed his slaves and they serve honorably in his cavalry. General Jackson owns no slaves. I will never own slaves. In any event, we've already begun our own process of emancipation, so it will be gone in a few years anyhow. I consider the institution distasteful and I'm glad it will die out."

Thomas laughed, "You command an army under the control of slave owners in Richmond. They will never let it die out. Your victory is slavery's victory. Your defense of Atlanta is the defense of slavery. Will your people honor their word to emancipate their conscripted blacks or just return them to slavery? We freed them to fight for the Union; your army has them fight for their fellow colored man to remain a slave."

"The South did not secede for slavery," Johnston said, trying to remain calm. "Had the north not demanded protectionist tariffs that drained southern money to pay for northern roads and canals, or insulted us for thirty years, we likely never would have seceded."

"Reread South Carolina's secession document," Thomas countered.

"I could also suggest you read our declaration of independence," Johnston added. "Our emancipation bill itself is proof enough. Besides, I did not join the army to defend slavery. I joined to defend the right of states to be free from external coercion. We delegated certain power to the federal government; we don't want a centralized government that can dictate where people can settle or take 3/4 of the budget to spend in one part of the nation. We just want to be left alone. Much like our own forefathers in the Revolution. General Lee's father fought with Washington. My father carried the sword I now carry in the Revolution. Even Jefferson and others in 1794 said we should separate into two nations, north and south, as our cultures are just too different."

"Don't compare your misguided struggle with that of our revolutionary forefathers," Thomas said, shaking his head. "The patriots of old had no recourse but revolution against King George III, since they weren't represented in Parliament. The southern states had representation in Congress till they seceded. You faced no tyrant; revolution is only justified when faced with a tyrant like King George."

"What do you call King Abraham's suspension of habeas corpus without Congress's approval? Arresting legislators who speak out against him? Exiling Congressman Vallandigham? Closing papers which speak out against Lincoln's War? How is that not the action of a tyrant? Hasn't he even proposed on several occasions deporting all blacks from the country to Panama, or even Africa, countries they've never known? And when we sent peace commissioners to meet to discuss purchasing federal forts, he pretended they didn't exist and refused to meet them. And he violated the truce President Buchanan and South Carolina agreed to, and lied to the peace commissioners, denying he was sending any armed force to Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens, thus making it necessary to fire upon the fort."

He continued, "What good does representation do us, when the north closed off settlement of the west to southerners, to reserve those lands for their people to cement their hold on power? We'd be outvoted on every issue soon, given the different sizes of our populations. How is that representation when we are to be continually denied our equal say? What right does a corporate lawyer from Illinois have to tell a farmer in Georgia how he organizes his life? Or the President to the Governor of Virginia?"

Thomas sat back and sipped his wine.

"I suppose we could go back and forth, General Johnston, for some time without coming to any kind of agreement on things. I am not a political man. To me, all that matters is my oath that I took at West Point. I kept it, even though it tore my heart when Virginia seceded. You broke your oath, and now wage war on the very government you once swore to protect. For that sir, I shall pray to God for your soul, and those of your fellow soldiers."

Johnston took a long sip from his glass. It was a fine vintage. Thomas's last statement essentially ended the conversation. Thomas went back to his beef, not caring if he were being polite in eating.

Johnston stood, telling him, "I will have proper quarters prepared for you, General Thomas. I will also sent a message to General Sherman under flag of truce informing him of your sttus, so he may then inform your wife. When my government informs me of its intentions regarding your situation, I will inform you."

"Thank you."

"Do you want me to send a message to your family in Virginia?"

"No, thank you," Thomas said, having thought for a moment.

Johnston nodded, understanding. "The war is hard on everyone."

**

Richmond, VA (October 11)

While Congress had many things on its plate, it took some time to authorize the creation of a series of medals and ribbons in response to Johnston's successful defense of Atlanta.

The 'Defense of Atlanta' ribbon, a red/white/red ribbon, with a small bronze medal containing the seal of Georgia, and around it "Defense of Atlanta" "Army of Tennessee."

The year 1864 between them on the right, and 'Oct.20' on the left. Everyone in the Army of Tennessee would get one...when materials and resources were available to do so.

The "Bonnie Blue" Ribbon, blue with a single white star on it, for those who served in the provisional armies of their respective states.

The 'National Defense' Service Ribbon would go to all troops who served honorably, after peace would be achieved.

Washington, DC (October 11)

Outside Lincoln's office there was a slight commotion. "Mr. President, Secretary Stanton is here to see you."

A few moments later, the Secretary of War walked into the room, greeted him, and sat in the chair across from him.

"Mr. President, I have some very bad news to report," Stanton said after gathering himself for a moment.

"I hope it's not more news from Petersburg," Lincoln said with a sigh. Lee was resisting most tenaciously there.

"No sir, it's from Georgia, not Petersburg," Stanton countered.

Lincoln sighed again. "We have endured Bull Run, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Bull Run...again...so I believe we shall endure it again. Out with it."

"Very well, Mr. President," Stanton said. "Yesterday, while our Army of the Cumberland was crossing a creek north of Atlanta, the rebel army attacked and defeated them while they were separated from a large portion of the rest of our forces by several miles. Roughly ten thousand prisoners were taken, including General Thomas, and over ten thousand either killed or wounded. We also lost vast amounts of critical supplies, including ammunition, rifles, small arms, cannon, and more. The Army of the Cumberland has been shattered."

Lincoln's face remained stoic. He strove so hard to see his vision of America come to fruition - a central bank regulating the money; internal improvements making capital flow east to west and back in the form of vast untapped resources; colonizing the blacks out of the north and west; and finally a nationalized government to rule over the chaotic individualists in the states. And now that vision, begun by Henry Clay, seemed to be in dread danger.

Stanton continued talking, relaying the details of the Battle of Peachtree Creek. It was as bad as he feared.

After a moment Lincoln spoke. "If I understand all that you tell me, we may have just lost the election. And with it, the war."

"No sir," Stanton said quickly. "Despite this, our army is still outside Atlanta, and still outnumbers the rebels. We have recovered from defeats before, and we can do it again."

"Can we?" Lincoln asked. "They've enlisted their slaves, just like we enlisted their slaves to fight against them. It's not just rumor and denials now. News of that will come out. The people are hungry for peace and the treasury is coming up on empty. Democrats are telling every crowd which will listen that this war is a failure and victory is impossible."

"Mr President, this is a terrible defeat, yes. But we can recover, and we can shore of the electoral college," Stanton said.

"If we make territories states..." Lincoln said, as he walked over to the map, looking to the west. He pointed over next to Union-held California. Nevada was organized. Utah? No, not those polygamists out there. Maybe Columbia...they'd been petitioning recently.

"Pack your bags, Edwin," Lincoln said finally. "We're taking a trip."

"To where Mr President?" Stanton asked.

"We're going to see General Grant in Virginia. While Congress works on statehood, I need to see my commander-in-chief."

**

Atlanta, GA (October 11)

General Joseph Johnston thought if only he could get to the north side of the Chattahoochee, he could trap Sherman south of the river. Unfortunately, two of his corps had suffered heavy losses, and their divisions had become disorganized. Utilizing the forces Albert Sidney Johnston had luckily trained, he was slowly beginning to rebuild his army with freedmen, placing them into divisions with people close to their home counties and states. For the moment, he couldn't tell if Sherman intended to make a retreat or was just keeping his options open.

Elsewhere, Sergeant Johnson was working on the battlefield of Peachtree Creek with a shovel. He wiped away the sweat from his brow as he was digging a grave, in a row for his fallen comrades.

"Take a break, James," said his captain, Jose Cleary, originally from Rio Grande. "You've earned it."

"Thank you sir, but I just want to get this done as quickly as we can. Our friends are owed that much," he replied.

"As you wish," Cleary said.

The men of his company, K, were once a hundred, but now 63 remained. They had taken most of day on the 21st and were digging shallow graves for their men. Where possible, they scratched names, ranks, divisions, and units onto the crosses. Most soldiers' buttons were state-specific, so it was easy to tell from where it came. Once the graves were dug, the bodies were placed in each, and the troops held a small service for them. As was customary by now, taps was played once the pastor had finished a reading of Psalm 23 and spoke of the soldiers' devotion to Christ; life in the army meant a great many soldiers had become born-again believers.

Johnson took a small nap near a tree when the service was done. He was wiped out. In an instant it seemed, he was awoken by Robert.

"Jim, wake up," he said, shaking his friend.

"What is it?" he mumbled, not wanting to move. If he moved, it'd be harder to get back to sleep.

"General Cleburne is here to see you."

That's when Sergeant Johnson woke up like a splash of water hit his face. Cleburne was standing before him, waiting. He scrambled up to his feet, quickly brushed off his uniform, and saluted. "Sorry sir!"

"At ease, Johnson," Ceburne said. "I just came by to give this to your regimental commander."

He pulled out a paper from his uniform coat pocket, and gave it to Captain Cleary.

"What is it?" Johnson asked.

"Orders," he answered. "Captain Cleary has received a promotion to Major. You have been promoted to Lieutenant, effective immediately. The official confirmation will come when the War Department manages to take care of the paperwork."

"Lieutenant?" Johnson repeated, still surprised.

"You shouldn't be surprised, Johnson. You captured the highest ranking Union officer yet, and your record has been exemplary. Honestly I can't figure out why you weren't made officer some time ago."

"I offered to send his name in for promotion to lieutenant several times before, sir," Cleary explained. "He always declined."

"Is that so?" Cleburne asked. "Why is that?"

Cleary looked to Johnson, the look on his face one telling him he should answer. He really didn't have an answer.

"Well, not this time, son. As commander of your corps, I am not offering a promotion, I am ordering you to take it. Is that clear, Lieutenant Johnson?" he said, stressing the new title.

"Perfectly, sir."

"Very well. Congratulations," said the general, extending his hand.

After Cleburne left and his men cheered. He feared being in charge of half the regiment now. Being a sergeant was a small amount of responsibility. This, however, was a whole new level.

**

Chattahoochee River (October 12)

General Sherman was leaning against a tree, smoking a cigar, and gazing south towards Atlanta. Five or so miles away, but it might as well be Moscow for all he could do to get there. Just three days ago, he had an army of over 100,000 men. After the Battle of Peachtree Creek, he had maybe 75,000, and maybe half that could be considered reliable in a fight. He bet the Confederates, flush with their victory, were likely getting those reinforcements from Virginia, and all the freedmen the other General Johnston had been training. And they could equip them now with all that captured cannon and musket. That was likely one of the big things keeping the Confederates from fielding them in battle till now. Sherman didn't know what kind of casualties they had suffered, nor how many or if Lee were sending troops. All he knew was he needed to put the river between him and the Confederates so he could regroup. General McPherson asked whom he would have replace Thomas, who was now prisoner, according to the message sent under flag of truce. Sherman put Oliver Howard, despite Hooker being the senior rank.

"No dishonor in it sir," Johnson said as he led the general.

"What?"

"No dishonor in being captured, sir. It happens to a lot of soldiers," he added.

"Oh," Thomas replied. He'd kind of expected him to whoop and holler, but he'd been remarkably respectful and low-key about it. "I suppose you're right."

"Better than being dead, sir," Johnson said.

Thomas considered what his sisters and family would say, not to mention his reputation. "I don't know about that, sergeant."

**

As evening began to fall, the Confederates kept up the pressure, Hardee, Cleburne and Stewart keeping their troops going forward. Moving north on their horses, the generals saw their men advancing in barely a semblance of order. Cleburne noticed the absence of artillery fire. Most of the Union batteries had fallen to the Confederates, and most of their artillery crews must have pulled back across the creek.

As they approached, they happened upon General Thomas.

"That's General Thomas!" Hardee exclaimed. He trotted forward, followed by Cleburne.

"Is that you, William?" Thomas asked as the two men in gray approached.

"It is George," Hardee nodded. "Are you injured?"

"No," Thomas answered with a little sadness.

"My God, I never expected to take you prisoner," Hardee said.

Thomas sighed and gave a slight nod, but otherwise kept silent.

"Being a prisoner won't be so bad George. I spent some time as a prisoner of the Mexicans back in '46. Back in the good old days, huh?" Hardee said, trying to help his friend's mood.

Thomas's mouth did come to a slight smile at his friend's remembrance.

"May I present my fellow corps commander, General Patrick Cleburne," he said, gesturing to the man to his right.

"General Cleburne," Thomas nodded, with little enthusiasm. "I've heard a great deal about you. You're the man who got the Confederates to emancipate their slaves."

"I merely got the snowball rolling downhill, sir," Cleburne said with some modesty. "Any man will fight for his home state, regardless of color. It is an honor to meet you sir."

"I understand your corps broke my line."

"Yes sir, my men including our freedmen had that honor."

"A fine performance," Thomas said. His voice was flat, lacking any enthusiasm. It was understandable, given the circumstance.

"Thank you sir," Cleburne said, still being polite.

"Are my men treating you properly?" Hardee asked.

"Yes," Thomas answered. "This man is the soldier who captured me." He pointed to Sergeant Johnson. "He has been most gracious."

"What is your name, young man?" Hardee asked.

"Sergeant James David Johnson, 4th Georgia, sir," he answered smartly.

Cleburne recognized the man, seeing him during his weekly reviews of his brigades and divisions, for the past few months, ensuring the freedmen who'd been trickling in had been taken in and trained properly and treated well. Beside the sergeant, two privates, Darryl Polite and Robert Crane, both carrying a rifle and two flags themselves.

"You'll be noted in our dispatches for this, sergeant," Cleburne told him. "Few soldiers can say they captured the commanding officer of the opposing army."

"Thank you sir."

"George, you will be my guest at dinner this evening," Hardee said.

"Thank you, but I'm afraid I must decline."

"Don't be like that, George! We're old friends! We can swap old stories from back at West Point and in Mexico!"

"Please forgive me William. I don't mean you any disrespect. I simply cannot find it in my heard to celebrate even this reunion with an old friend when my army lies in ruins. I just suffered one of the worst defeats an army has experienced in the history of this continent," Thomas explained. "Besides, I do not wish to share a table with those who turned their backs on their country."

Hardee's face darkened. His friend's words stung. "Suit yourself, George. If we must be frank, I would rather not endure the company of a man who betrayed his state. Sergeant Johnson, please escort General Thomas to General Johnston's headquarters."

"Yes sir," he saluted. He tilted his head south, and Thomas walked on with Darryl and Robert joining them.

**

Elsewhere, as Sherman found the Army of Tennessee manning the defenses, reinforced not just by Georgia Militia, but around 20,000 black troops, a messenger ran to him.

"General Sherman, sir!"

"What? What is it?"

"We've been beaten sir! The rebels broke through Thomas's line at the center, and everything fell apart! The rebs have routed the Army of the Cumberland!"

"My God!" gasped McPherson

"It can't be true!" Sherman said gruffly.

"There's no doubt about it, sir! Several officers from the Army of the Cumberland arrived at headquarters in a panic! They say the rebels started attacking at one o'clock. Things went well at first, but then the division in the center just collapsed and rebels just poured in, and the line fell apart."

Sherman's mind was racing. The possibility for a true complete disaster was very real.

"Where is General Thomas?"

"No one knows sir. No word for several hours."

Sherman felt a stab to his heart at that. He tried to concentrate, shaking his head clear. If Thomas had been defeated, Johnston could strike north and capture the Union bridges along the Chattahoochee, trapping him and the remnants of Thomas's army on the south side of the river. He remembered Grant's warning about Jubal Early possibly coming down with 20,000 more troops. Could they have arrived?

"What's the situation?" he demanded.

"General Thomas is either dead or captured, sir. Hooker said he is taking command of the Army of the Cumberland and will try to withdraw to the north bank of Peachtree Creek as orderly as possible. He is urgently requesting reinforcements."

"Thomas dead?" Sherman said, stunned. Then the thought of Hooker at the head of the army, if only temporarily, filled him with dread. While the highest ranking commander there, Sherman thought him incompetent and a blowhard.

"Shall we attack sir?" asked McPherson.

Sherman's mind was spinning with all the what-ifs. "What?"

"Shall I attack, sir? If we attack, we may create a diversion which would enable the Army of the Cumberland to escape."

"No," he replied quickly. "No, an attack is out of the question. We need to get the Army of the Tennessee back to the north side of Atlanta quickly. Schofield too. If Thomas has been defeated, Johnston may try to follow up on that victory by capturing our army as they cross the river."

"Surely it can't be that bad, Cump. Perhaps Hooker can rally the men there and restore order and salvage the situation."

Sherman didn't reply, just shook his head.

"What do we do?" McPherson asked again.

"Message to Schofield," he said, turning to a courier. "Move his army at once to assist the Army of the Cumberland in crossing the river, while moving one division to Buckhead to prevent any rebel movements on our bridges. Wheeler's cavalry might be roaming about."

The courier saluted and left on his horse at a gallop.

Sherman turned to McPherson, "James, your army must march back too. I know your men are already tired, but they must march all night. We have to get them away from the east side of the city to avoid any possible traps the rebels might try to catch us in."

**

Cleburne took control of the situation, which calmed the Confederates, soothed their frayed nerves, and restored their confidence. He led the men across Collier's Bridge, after a good twenty minutes of fighting, holding it against the Yankees, as the bulk of the Yankee army was still on the south side. He had his staff officers get reinforcements to help hold the bridge, and had the men cut down trees on the north side to create a barricade on the south side of the bridge. He was a bit worried; he had maybe a thousand men on his side against the horde of Yankees coming his way, terror in their faces.

They fired, the Confederates unleashing their musket fire on the terrified opponents. Scores of Union troops fell, the wounded rapidly trampled under the boots of their comrades. Cleburne tried not to hear their screams. A formidable black horse carrying a Union officer emerged from the woods, trying to rally his men. His face was not one of fear, but rage...and determination.

"Form up men! I don't give a damn your regiment! Form up!" he yelled out. The frightened blue-coats rallied around him. "Now charge!"

The man and his horse sped forward. The Confederates fired furiously at them all. The Union officer was killed instantly. At this range, the Confederates couldn't miss. But the momentum of the enemy kept driving them forward. The Yankees tried the bridge, but that devolved into both muskets and bayonets. Even Cleburne felt a hit on his leg, stung by a bullet. Some of Cleburne's men instinctively stepped back from the line of fire to reload and pass muskets forward, maintaining some level of fire during the hand-to-hand.

He was struggling to reload, when he say his men left and right falling; fear began to take hold as he saw blue left and right across from him as far as he could see. Then he herd another sound...the Rebel Yell yipping behind them. The Yankees seemed to abandon the idea of taking the bridge, threw their weapons away and jumped down into the ravine. The drop of about 8-9 feet was a lot, but better that that than being shot or captured.

While reloading, Cleburne saw the most horrifying sight yet in his years of combat. The first few men who jumped ran to the other side, splashing in the waist-high creek. They struggled up the high and steep northern bank, gripping the exposed roots of trees and rocks to try to pull themselves up and out. As they did, more Union troops dropped down into the basin and grabbed the feet of the men above them, inadvertently pulling them back down into the basin. Only a few were able to pull themselves up the bank and run off to the north to safety. More and more troops were dropping into the basin trying to escape. Some even when unwillingly, knocked down into the ravine by the wave of men from the south side, many who were still firing back at the Confederates behind them.

Suddenly, something seemed to just click, and hundreds of the Union troops just dropped their rifles and seemed to decide their only chance of escape was the ravine. They jumped too. And suddenly the creek became a mass of blue-coated men, scrambling wildly for the other side of the bank and shouting in confusion. A few lucky men made it; most didn't. Crowded in, they got in each other's way, hindered their movements, and turned the creek into a mass of terrified men.

Finally, the Confederates came up on the other side. You can understand what happened next. After hours of fighting, most men reach a breaking point, and men don't question the morality of firing on defenseless men. Officers ordered the men to fire, and they just poured down their fire and fury on the men in the creek. Most had thrown their muskets away, so there was almost no return fire. Their screams were unlike anything Cleburne had heard at any point during the war. Not all the death was due to their bullets. In their rush to get across the north bank, many of the unlucky Union troops were shoved under the waist-high creek waters by the weight of their comrades. There they flailed about as the others ran over them, unthinkingly pinning them down under water till they stopped moved, drowned, or were crushed.

The south bank was in flames as the Confederates poured shot after shot into the mass. Cries of 'don't shoot!' 'we surrender!' went unheeded as Confederates shouted back "Keep firing!" and "Kill them all!"

Cleburne had seen combat do this to men. The nightmare that is battle and war could most certainly transform men into animals. Cleburne watched as the Yankees stopped trying to push over the bridge. The creek was crystal clear water yesterday; today it was red with blood. He wanted to shout to stop the carnage, but another voice told him every Yankee stopped here was one less person firing at him and his men on the battlefield tomorrow. War is most definitely hell.

He didn't know how long he watched, but the Confederates finally stopped their firing as the officers finally regained control of their men, and call for the Yankees to return to the south bank and surrender. Many did, and others continued trying to escape, using the piles of bodies of their dead comrades and protesting wounded as their stairs to ascend the steep bank and run north. As far as the eye could see, Peachtree Creek was clogged with the bodies of dead and wounded Union soldiers.

**

Johnston was meeting with his staff officers to get the report of the day while in the field on horseback. Artillery and muskets still fired off, but the sound was fading with the night, and Johnston was glad for that. Steward, Hardee, and Cleburne returned. The ground south of Peachtree Creek was so covered with Union dead you could walk two miles stepping from one corpse to the next and never touch the ground. It was Cleburne's breakthrough that turned the tide of battle decidedly in their favor. His use of tactics rather than just brute force is what did it.

By their reports, they had about 10,000 prisoners; killed around 8000 Union soldiers, captured 64 artillery, captured 48 battle-flags, and a large quantity of ammunition, small arms, and other supplies. The telegram he sent to Davis made the President very happy that night.

**

Sherman was riding the saddle slowly ahead of the others. He was nauseated and dizzy, and his thoughts were unfocused. His hands trembled. It was coming up to midnight, and with it the most disastrous day of his life was ending, and he was glad. He remembered the great battles of history - Saratoga, Hastings - would Peachtree Creek be added to that list? He remembered his early service in the war, when he had been essentially kicked out of the army under suspicion of insanity. His wife cared for him tenderly, but he had almost committed suicide. The demons that tormented him, he could feel them reaching out for him again, trying to pull him down into the darkness. He felt his mind going there. He closed his eyes, willing the demons away again.

What remained of the Army of the Cumberland was a shattered force maybe half its original size of 60,000. Many men were dead, wounded, or in no condition to fight. Many lost their weapons as well. Many division and brigade commanders had also been killed, captured, or wounded in addition to General Thomas. In many brigades, the highest ranking officers were now captains, according to his staff officers.

Until he could restore the Army of the Cumberland, he had just 40,000 men or so in McPherson and Schofield's armies. In terms of effective army size, it was now very possible Johnston outnumbered him.

McPherson and Schofield tried to persuade him to leave their armies on the south bank, while the Army of the Cumberland retreated to the north bank of the Chattahoochee to rest and refit, but he rebuffed them and told them they needed to avoid being trapped with a river at their backs. They advised it would be tougher to resume the offensive on Atlanta if they retreated. Sherman yelled back "Forget Atlanta! We have to look to the safety of our armies, not Atlanta!"

He calmed down, and reiterated that they needed to retreat to avoid risking another defeat, perhaps one greater than that Thomas experienced.

**

At the Niles house, men were celebrating, partaking in some liquor to celebrate and make toasts, as Johnston dismounted his horse.

"Where's General Thomas?" he asked.

"In your room, sir. We gave him dinner, and posted guards outside the door," said the officer nearest the general.

He climbed the steps to find General George Thomas sitting before an untouched plate of roast beef. As he saw Johnston, he stood up sharply and saluted.

"General Johnston," he said, his hand in a fine salute.

"General Thomas," Johnston said, returning the salute. He paused for a moment, before continuing, "I do hope I'm not disturbing your dinner."

"I'm sure you'll understand why I haven't much of an appetite. Besides, I doubt the other prisoners are eating this well."

"Your men are being treated properly, General. They are being fed the rations we captured during battle. I know you must be hungry. Please eat," he said, gesturing to the plate.

Thomas began eating slowly and reluctantly. Johnston continued.

"I want you to know we will do everything we can to make your captivity comfortable. It may be some time before you are released. If I'm not mistaken, the United States hold no Confederate officer of equivalent rank to yours, so prisoner exchange is a little more complicated."

"General Grant terminated prisoner exchanges some time ago, so it really makes no difference," Thomas said.

"Regrettable I must say," Johnston added. "Possibly inhumane, letting prisoners languish."

Thomas pulled his head up, "It was your so-called government's decision to treat captured black soldiers as if they were escaped slaves prompting his decision. If Forrest hadn't been encouraging desertions from amongst our ranks perhaps this could've been avoided."

"I can't say much regarding General Forrest, as I haven't worked closely with him," Johnston admitted.

Thomas just grunted again. He as upset, and Johnston really couldn't blame him. He'd be just as upset in Thomas's position. A servant brought Johnston plate for him after he sat down across from Thomas, and he began to eat.

"I have sent a telegram to our Department of War in Richmond asking as to your future circumstances. Since you are the highest-ranking officer we have yet captured, I am sure you will be accorded special consideration," Johnston said as he took a bite of his roast beef. It was delicious.

"No," his counterpart shook his head. "I want no special consideration apart from the same given my fellow soldiers."

"I will inform my government of your request," Johnston said in all politeness. "It does credit to your character. Given that you are a native Virginian they should be more likely to grant you that."

Thomas picked at his sweet potatoes and roast beef. Johnston walked over to grab some wine and poured a glass. "Would you drink a glass of wine with me, General? It has become more expensive due to the blockade, but it's not yet entirely unobtainable."

He poured two glasses before Thomas could respond, and set them down at the table.

"I might as well," Thomas finally said, picking at his food. "Today my army was destroyed. A glass of wine won't undo that, but I guess it won't hurt. As for those who believe I betrayed my state, well, I believe they betrayed their country."

"My country is Virginia," Johnston replied politely, as he took another bite. "The same was true of you once, as I recall. Our state was sovereign and independent as of 1783 and reserved its right to leave the Union if it so chose. If state cannot leave and is forced back in against its will, then its people are not truly free."

Thomas didn't answer the point, but continued, "You took an oath at West Point to protect the United States and the Constitution, yet you broke your oath, and instead became the servant of those radicals who tore our country apart for fear of Lincoln harming their interest in slavery."

"One could say the same of the radicals from New England who formed the Republican party broke the trust when they funded the terrorist John Brown to murder southerners in Kansas and Harpers Ferry, trying to foment slave revolts and widespread murder, and continued insulting the south for the last 30 years, calling us all manner of abominations for engaging in the same thing New England started in 1637. I myself own no slaves; neither does General Lee. General Forrest freed his slaves and they serve honorably in his cavalry. General Jackson owns no slaves. I will never own slaves. In any event, we've already begun our own process of emancipation, so it will be gone in a few years anyhow. I consider the institution distasteful and I'm glad it will die out."

Thomas laughed, "You command an army under the control of slave owners in Richmond. They will never let it die out. Your victory is slavery's victory. Your defense of Atlanta is the defense of slavery. Will your people honor their word to emancipate their conscripted blacks or just return them to slavery? We freed them to fight for the Union; your army has them fight for their fellow colored man to remain a slave."

"The South did not secede for slavery," Johnston said, trying to remain calm. "Had the north not demanded protectionist tariffs that drained southern money to pay for northern roads and canals, or insulted us for thirty years, we likely never would have seceded."

"Reread South Carolina's secession document," Thomas countered.

"I could also suggest you read our declaration of independence," Johnston added. "Our emancipation bill itself is proof enough. Besides, I did not join the army to defend slavery. I joined to defend the right of states to be free from external coercion. We delegated certain power to the federal government; we don't want a centralized government that can dictate where people can settle or take 3/4 of the budget to spend in one part of the nation. We just want to be left alone. Much like our own forefathers in the Revolution. General Lee's father fought with Washington. My father carried the sword I now carry in the Revolution. Even Jefferson and others in 1794 said we should separate into two nations, north and south, as our cultures are just too different."

"Don't compare your misguided struggle with that of our revolutionary forefathers," Thomas said, shaking his head. "The patriots of old had no recourse but revolution against King George III, since they weren't represented in Parliament. The southern states had representation in Congress till they seceded. You faced no tyrant; revolution is only justified when faced with a tyrant like King George."

"What do you call King Abraham's suspension of habeas corpus without Congress's approval? Arresting legislators who speak out against him? Exiling Congressman Vallandigham? Closing papers which speak out against Lincoln's War? How is that not the action of a tyrant? Hasn't he even proposed on several occasions deporting all blacks from the country to Panama, or even Africa, countries they've never known? And when we sent peace commissioners to meet to discuss purchasing federal forts, he pretended they didn't exist and refused to meet them. And he violated the truce President Buchanan and South Carolina agreed to, and lied to the peace commissioners, denying he was sending any armed force to Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens, thus making it necessary to fire upon the fort."

He continued, "What good does representation do us, when the north closed off settlement of the west to southerners, to reserve those lands for their people to cement their hold on power? We'd be outvoted on every issue soon, given the different sizes of our populations. How is that representation when we are to be continually denied our equal say? What right does a corporate lawyer from Illinois have to tell a farmer in Georgia how he organizes his life? Or the President to the Governor of Virginia?"

Thomas sat back and sipped his wine.

"I suppose we could go back and forth, General Johnston, for some time without coming to any kind of agreement on things. I am not a political man. To me, all that matters is my oath that I took at West Point. I kept it, even though it tore my heart when Virginia seceded. You broke your oath, and now wage war on the very government you once swore to protect. For that sir, I shall pray to God for your soul, and those of your fellow soldiers."

Johnston took a long sip from his glass. It was a fine vintage. Thomas's last statement essentially ended the conversation. Thomas went back to his beef, not caring if he were being polite in eating.

Johnston stood, telling him, "I will have proper quarters prepared for you, General Thomas. I will also sent a message to General Sherman under flag of truce informing him of your sttus, so he may then inform your wife. When my government informs me of its intentions regarding your situation, I will inform you."

"Thank you."

"Do you want me to send a message to your family in Virginia?"

"No, thank you," Thomas said, having thought for a moment.

Johnston nodded, understanding. "The war is hard on everyone."

**

Richmond, VA (October 11)

While Congress had many things on its plate, it took some time to authorize the creation of a series of medals and ribbons in response to Johnston's successful defense of Atlanta.

The 'Defense of Atlanta' ribbon, a red/white/red ribbon, with a small bronze medal containing the seal of Georgia, and around it "Defense of Atlanta" "Army of Tennessee."

The year 1864 between them on the right, and 'Oct.20' on the left. Everyone in the Army of Tennessee would get one...when materials and resources were available to do so.

The "Bonnie Blue" Ribbon, blue with a single white star on it, for those who served in the provisional armies of their respective states.

The 'National Defense' Service Ribbon would go to all troops who served honorably, after peace would be achieved.

Washington, DC (October 11)

Outside Lincoln's office there was a slight commotion. "Mr. President, Secretary Stanton is here to see you."

A few moments later, the Secretary of War walked into the room, greeted him, and sat in the chair across from him.

"Mr. President, I have some very bad news to report," Stanton said after gathering himself for a moment.

"I hope it's not more news from Petersburg," Lincoln said with a sigh. Lee was resisting most tenaciously there.

"No sir, it's from Georgia, not Petersburg," Stanton countered.

Lincoln sighed again. "We have endured Bull Run, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Bull Run...again...so I believe we shall endure it again. Out with it."

"Very well, Mr. President," Stanton said. "Yesterday, while our Army of the Cumberland was crossing a creek north of Atlanta, the rebel army attacked and defeated them while they were separated from a large portion of the rest of our forces by several miles. Roughly ten thousand prisoners were taken, including General Thomas, and over ten thousand either killed or wounded. We also lost vast amounts of critical supplies, including ammunition, rifles, small arms, cannon, and more. The Army of the Cumberland has been shattered."

Lincoln's face remained stoic. He strove so hard to see his vision of America come to fruition - a central bank regulating the money; internal improvements making capital flow east to west and back in the form of vast untapped resources; colonizing the blacks out of the north and west; and finally a nationalized government to rule over the chaotic individualists in the states. And now that vision, begun by Henry Clay, seemed to be in dread danger.

Stanton continued talking, relaying the details of the Battle of Peachtree Creek. It was as bad as he feared.

After a moment Lincoln spoke. "If I understand all that you tell me, we may have just lost the election. And with it, the war."

"No sir," Stanton said quickly. "Despite this, our army is still outside Atlanta, and still outnumbers the rebels. We have recovered from defeats before, and we can do it again."

"Can we?" Lincoln asked. "They've enlisted their slaves, just like we enlisted their slaves to fight against them. It's not just rumor and denials now. News of that will come out. The people are hungry for peace and the treasury is coming up on empty. Democrats are telling every crowd which will listen that this war is a failure and victory is impossible."

"Mr President, this is a terrible defeat, yes. But we can recover, and we can shore of the electoral college," Stanton said.

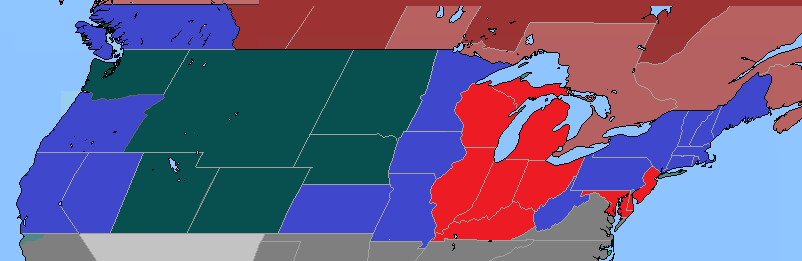

"If we make territories states..." Lincoln said, as he walked over to the map, looking to the west. He pointed over next to Union-held California. Nevada was organized. Utah? No, not those polygamists out there. Maybe Columbia...they'd been petitioning recently.

"Pack your bags, Edwin," Lincoln said finally. "We're taking a trip."

"To where Mr President?" Stanton asked.

"We're going to see General Grant in Virginia. While Congress works on statehood, I need to see my commander-in-chief."

**

Atlanta, GA (October 11)

General Joseph Johnston thought if only he could get to the north side of the Chattahoochee, he could trap Sherman south of the river. Unfortunately, two of his corps had suffered heavy losses, and their divisions had become disorganized. Utilizing the forces Albert Sidney Johnston had luckily trained, he was slowly beginning to rebuild his army with freedmen, placing them into divisions with people close to their home counties and states. For the moment, he couldn't tell if Sherman intended to make a retreat or was just keeping his options open.

Elsewhere, Sergeant Johnson was working on the battlefield of Peachtree Creek with a shovel. He wiped away the sweat from his brow as he was digging a grave, in a row for his fallen comrades.

"Take a break, James," said his captain, Jose Cleary, originally from Rio Grande. "You've earned it."

"Thank you sir, but I just want to get this done as quickly as we can. Our friends are owed that much," he replied.

"As you wish," Cleary said.

The men of his company, K, were once a hundred, but now 63 remained. They had taken most of day on the 21st and were digging shallow graves for their men. Where possible, they scratched names, ranks, divisions, and units onto the crosses. Most soldiers' buttons were state-specific, so it was easy to tell from where it came. Once the graves were dug, the bodies were placed in each, and the troops held a small service for them. As was customary by now, taps was played once the pastor had finished a reading of Psalm 23 and spoke of the soldiers' devotion to Christ; life in the army meant a great many soldiers had become born-again believers.

Johnson took a small nap near a tree when the service was done. He was wiped out. In an instant it seemed, he was awoken by Robert.

"Jim, wake up," he said, shaking his friend.

"What is it?" he mumbled, not wanting to move. If he moved, it'd be harder to get back to sleep.

"General Cleburne is here to see you."

That's when Sergeant Johnson woke up like a splash of water hit his face. Cleburne was standing before him, waiting. He scrambled up to his feet, quickly brushed off his uniform, and saluted. "Sorry sir!"

"At ease, Johnson," Ceburne said. "I just came by to give this to your regimental commander."

He pulled out a paper from his uniform coat pocket, and gave it to Captain Cleary.

"What is it?" Johnson asked.

"Orders," he answered. "Captain Cleary has received a promotion to Major. You have been promoted to Lieutenant, effective immediately. The official confirmation will come when the War Department manages to take care of the paperwork."

"Lieutenant?" Johnson repeated, still surprised.

"You shouldn't be surprised, Johnson. You captured the highest ranking Union officer yet, and your record has been exemplary. Honestly I can't figure out why you weren't made officer some time ago."

"I offered to send his name in for promotion to lieutenant several times before, sir," Cleary explained. "He always declined."

"Is that so?" Cleburne asked. "Why is that?"

Cleary looked to Johnson, the look on his face one telling him he should answer. He really didn't have an answer.

"Well, not this time, son. As commander of your corps, I am not offering a promotion, I am ordering you to take it. Is that clear, Lieutenant Johnson?" he said, stressing the new title.

"Perfectly, sir."

"Very well. Congratulations," said the general, extending his hand.

After Cleburne left and his men cheered. He feared being in charge of half the regiment now. Being a sergeant was a small amount of responsibility. This, however, was a whole new level.

**

Chattahoochee River (October 12)

General Sherman was leaning against a tree, smoking a cigar, and gazing south towards Atlanta. Five or so miles away, but it might as well be Moscow for all he could do to get there. Just three days ago, he had an army of over 100,000 men. After the Battle of Peachtree Creek, he had maybe 75,000, and maybe half that could be considered reliable in a fight. He bet the Confederates, flush with their victory, were likely getting those reinforcements from Virginia, and all the freedmen the other General Johnston had been training. And they could equip them now with all that captured cannon and musket. That was likely one of the big things keeping the Confederates from fielding them in battle till now. Sherman didn't know what kind of casualties they had suffered, nor how many or if Lee were sending troops. All he knew was he needed to put the river between him and the Confederates so he could regroup. General McPherson asked whom he would have replace Thomas, who was now prisoner, according to the message sent under flag of truce. Sherman put Oliver Howard, despite Hooker being the senior rank.

Last edited:

Chapter 18: Grant Takes Charge

JJohnson

Banned

Eppes House, Virginia (October 13)

In the Eppes House, Lincoln, Grant, and Stanton meet to discuss the situation. The short of it is that they would need to send reinforcements from Virginia to make good on Sherman's losses. The Union would have to stop their actions against Jubal Early in the Shenandoah, which feeds Lee's army, if they were to hold the siege and reinforce Sherman. Grant suggests the Sixth Corps, with its three divisions, be sent immediately to Sherman. It was currently in eastern Tennessee maintaining the Union hold on the Kentucky/Tennessee area, so it could be to Sherman very quickly by rail. Per agreement with Lincoln and Stanton, Grant would journey to Georgia himself to get the situation of the army.

Richmond, Virginia (October 13)

Given the news, the President, Jefferson Davis, was holding a reception at the Confederate Executive Mansion, with the social well-to-do congratulating him on the defense of Atlanta. He had a long reception line; the band even struck up 'Hail to the Chief'* when Davis entered the reception. His son, little Joe** woke up during the party and he went to put him back to bed. Secretary of State Judah Benjamin took President Davis aside and let him know that the British ambassador was conferring with his government about the action at Peachtree Creek, and Parliament was considering whether to recognize the Confederates.

*Hail to the Chief was used by both the US and CS Presidents at this point in actual history.

**Joe didn't fall from a balcony and die this timeline.

Outside Atlanta, GA (October 13)

Lieutenant Johnson was drilling the men in his company, for the first time giving the orders he'd been saying silently in his head the past three years. The company had been practicing and drilling to be ready to move against the Yankees in case they came back south, or they went across the river, whichever came first. His company was now back up to 100 men, forty-seven of which were freedmen. After several hours of drilling, they all were looking good and maneuvering like pros.

"Who the hell is that?" came the voice of Private Stephen Williams, red hair, freckles, good guy, but often had his head in the books when he needed to be focused on something else.

"Quiet in the ranks!" Johnson shouted, trying his best to keep order. But he could see the men in the ranks were fixated on something behind him. He turned to see a covered wagon, Sarah Emma Saylor being driven by one of her father's servants, Percival. Behind the wagon was one of the fattest cows Johnson had seen in a good while, and he could hear the clucking of chickens in the back; through the two passengers, he could make out plenty of leafy greens and other vegetables.

The ranks stirred, and the men licked their lips. That was the best-looking and most amount of food they'd seen in a good while, considering they'd been surviving mostly on cornmeal for months, since the blockade had strengthened. Johnson's pulse quickened at the sight of Sarah Emma, whom he didn't know if he'd see again before the Battle of Peachtree Creek. It was during that fight he realized there might be a bright spot in his future after all, if they managed to win this war.

"Lieutenant?" she said with a smile and a nod.

"Yes, Miss Saylor?" he said with an unconscious smile in his voice, though his face kept some control.

"I brought the food my father promised he would bring," she said.

The men behind him gave a hearty cheer, before he asked. "He did?"

"Did you not get the note?"

"It must've gotten delayed in the chaos of the battle," he admitted.

"What's going on here, Lieutenant?" asked Major Cleary, his half-Hispanic, half-Irish commanding officer, and also a good friend these past few months. Cleary wasn't a man of faith, but he was still a moral man and Jim valued the deep conversations they were able to have when they had the time to do so. He had a slightly dark complexion, brown eyes, and black hair, and was one of the best commanders that James David had the pleasure to serve with during the war.

"Mr. Saylor from Atlanta has sent us a wagon of provisions, sir."

Cleary took a hard look at the wagon. The cow, chickens, and vegetables looked to be more food than the 4th Georgia Infantry had seen in a month.

"Dear God, what possessed the man to send us all this?"

"Lieutenant Johnson saved my father's life, and mine, sir," Sarah Emma replied. "He felt these provisions would be a good way to say thank you to the men of the Confederate Army."

"Well we definitely won't turn this gift down!" Cleary said with a big smile.

Major Cleary organized a detail of men from the 4th Georgia to unload the wagon. In minutes, they had created a makeshift pen for the chickens, deciding to keep them for the eggs, rather than killing and eating them. The eggs would be a valuable source of protein for the army. The vegetables were piled up next to the pen, and the cow was herded off, its throat slit, and they commenced slaughtering the beast to start cooking its beef for dinner.

"Where'd your father get all this?" Cleary asked, a few minutes later.

"Perhaps the less you know, the better, sir," said Percival, who had asked them to call him Percy.

"I'll trust you on that, Percy," Cleary said. "Just promise me General Cleburne won't come down here and arrest me for pilfering."

Percy and Sarah Emma laughed, and she replied, "I can promise you that, Major."

As the evening progressed, Lt. Johnson introduced her to his Major, and the men of Company K, who performed a few simple drill maneuvers expertly under his command.

They conversed after the presentation. "Are you aware that Lieutenant Johnson here is a hero?"

"Oh, is he?" she said with an amused expression on her face. "Save any other damsels, did he?"

"Just you," Cleary chuckled. "But he did manage to capture General George Thomas, the commanding officer of the Army of the Cumberland."

"I don't recall him saying that the last letter he sent over to us," she said, giving him a glance.

"I didn't want to brag," he said.

"Well, all of Atlanta will soon know of your heroism," she smiled. She had a lovely smile with full lips, he noted. "My father will make sure of it."

"I hope to be spared the infamy," Johnson said. "I don't like fame. I just want to life my life in peace, to be honest."

"Well, if anything, my parents will know," she told him. "They will be happy to know they dined with the man who captured the South's most famous traitor."

"Miss Saylor, would you do us the honor of dining with us?" Major Cleary asked. "Thank to your father, we will be enjoying fresh beef for the first time in months. It would please us greatly to have you as our honored guest."

"So long as my man Percy dines with us as my chaperone," she said.

"Done," he replied.

As the evening progressed, Sarah Emma placed her arm in his as he walked her around the camp, showing her captured material, their camp, how they made do and recycled spent cartridges, and so on. They enjoyed roast beef stew with the vegetables and beef, while some of the men produced fiddles to give them some music. One even produced a hurdy-gurdy, a guitar-body he cranked with wooden piano-keys on it. His parents had come from Germany and England, so they knew of the instrument. He played some traditional tunes on it, and even played Dixie on the hurdy-gurdy.

"I didn't think your mother would let you come so close to the front," Johnson said to her later in the evening.

"Mother was opposed, but father wanted me to go. He is intent on making sure I grow into a capable woman like my other sisters, more focused on business than frivolous things like chatting and gossiping and fashion. He says in the future, women won't be coddled by their men folk, since the war has changed everything. Women are supporting troops in many areas formerly reserved for men."

"He may be right," Johnson admitted.

"I bought this food on my own, and drove it up on my own initiative," she said, proud of herself.

"Wasn't Percy with you?"

"Yes. Sorry. He chaperoned for my protection, and drove, but the dealing was my own," she clarified.

"I see," he said.

The two continued their conversation till she had to leave, with Miss Saylor telling him of the loss of her brother up in Lee's Army at Fredericksburg, and him telling her of the loss of his brother back at First Manassas.

"I think when this war finishes, we should make a memorial to the fallen," she said, as he walked her back to the wagon. "Something that we never forget their sacrifice for our independence and the principle of self-government."

"I'm sure the Yankees will just say we fought to preserve slavery and how we're just a bunch of sinners and horrible people for having a different opinion than they have," Johnson quipped.

"Well, when we win this war, they can kiss my grits," she said, shocking the new Lieutenant with her bluntness. Both laughed, as did Percy.

He whispered to Lt. Johnson, "Mr. Saylor, he likes you sir."

"Does he?" Johnson said, surprised a bit.

"Yes, he does. Heard him say so, sir."

"How about you, Percy?"

"I like you just fine sir. But you are an odd one," he said, as he climbed up into the wagon, and the two departed.

General Johnston also decided to dispatch General Wheeler and his cavalry to harass Sherman's supply lines, sending his 4000 cavalry north. Wheeler had been an issue, plotting behind his back with Hood before Hood had been killed in combat. Both got what they wanted out of the agreement - Johnston didn't have to deal with Wheeler, and Wheeler finally got to see some action. His appointment of Cleburne to Corps command was finally officially approved, as was Cleburne's promotion to Lieutenant General.

Richmond, VA (October 13)