You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dixie Forever: A Timeline

- Thread starter JJohnson

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 78 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 44: The Union and Confederates Enter the War Chapter 45: The War Comes to a Close Chapter 46: Winning the Peace if Possible Chapter 46.5: The Union and Confederate Progressives Chapter 47: The Roaring 20s! Chapter 48: Europe on the One Hand...and on the Other Hand Chapter 49: Asia's Progress Chapter 49.5: Confederate State Areas and Flag

Chapter 15: The Campaign Continues (Part 2)

JJohnson

Banned

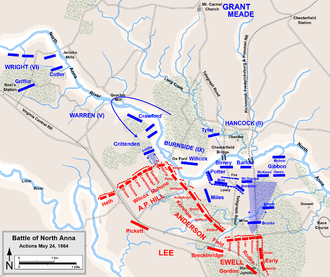

Battle of North Anna (May 27-29)

After Grant disengaged from the stalemate over at Spotsylvania Court House, he tried to lure Lee into a battle with Burnside, but he didn't fall for it. He lost the race to Lee's next defensive position, south of the North Anna River. Lee was unsure of Grant's intentions, but Jackson believed he was going to attack and urged his commander to build defensive works.

They devised a scheme of an inverted "V" to try to split the Union army when it advanced, and allow the Confederates to use interior lines to attack and defeat one wing, and prevent the other wing from reinforcing it in time. Surprisingly, Warren's V Corps missed Lee's army marching south right next to it.

Battle on the 28th

On the morning of the 28th, Grant sent additional troops south of the North Anna River. Wright's VI Corps crossed at Jericho Mills, and by 11 AM both Warren and Wright advanced to the Virginia Central Railroad. At 8 AM, Hancock's II Corps finally crossed the Chesterfield Bridge, with the 2nd US Sharpshooters and 20th Indiana dashing across the bridge to try to disperse a thin Confederate picket line. Down the river, the confederates had burned away the rail bridge, but soldiers from the 8th Ohio cut down a large tree so the men could cross single-file. The Union troops soon got a pontoon bridge set up and all of Maj. Gen. John Gibbon's division crossed. This is when Grant began to fall into Lee's trap. Seeing how easy it was to cross the river, he assumed the Confederates to be retreating. He wired command back in Washington: "The enemy have fallen back from North Anna. We are in pursuit."

The only visible opposition to their crossing was at Ox Ford, which Grant saw as simply a rear guard action, just an annoyance. So Grant ordered Burnside's IX Corps to deal with hit. Burnside had Brig. Gen. Samuel Crawford march upriver to Quarles Mill and seize the the ford there. Burnside ordered Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden's division to cross there at the ford, and follow the river's southern bank to Ox Ford, and attack the Confederate positions from the west.

Crittenden's lead brigade was unfortunately led by Brig. Gen. James Ledlie, known for his excessive consumption of alcohol in the field. Being intoxicated and ambitious, Ledlie decided to attack the Confederate position alone with just his brigade. His brigade encountered the Confederate earthworks, manned by Brig. Gen. William Mahone's division. Ledlie sent his 35th Massachusetts forward, but were immediately repulsed. Then he sent an officer back to ask for three more regiments from Crittenden as reinforcements. The division commander was surprised and had the officer instruct Ledlie not to attack till the full division crossed over.

Unfortunately by that time, Ledlie was completely drunk. When several Confederate artillery batteries on the earthworks were pointed out to him, he dismissed them and ordered a charge. His men started as a rain began to fall, and in their rush to get to the enemy's earthworks, the regiments got mixed up and confused. The Confederates waited to fire till they got close, which drove them into ditches for protection. A violent thunderstorm erupted, and though the 56th and 57th Massachusetts regiments tried to rally, Mahone's Mississippi troops stepped out of their earthworks and shot them down.

Col. Stephen Weld (56th MA) was wounded, and Lt. Col. Charles Chandler (57th MA) was mortally wounded. Soon all of Ledlie's men had to retreat, and they made it back to Quarles Mill. Despite his utterly miserable performance, Ledlie got praise from his division commander, saying his brigade "behaved gallantly." Ledlie was promoted to division command after this battle, and his drunkenness would continue to plague his men.

Hancock's II Corps began pushing south from Chesterfield Bridge about the same time Ledlie was just crossing over. Hancock ordered Gibbon's division to advance down the railroad. They pushed aside some Confederate skirmishers, but then ran into the earthworks, and most of his division was engaged. The fighting was interrupted by the thunderstorm, since men on both sides were worried it would ruin their gunpowder. As the rain slacked off, Maj. Gen. David Birney's division came to Gibbon's aid, but even both at once couldn't break the Confederate line.

The Union army was doing precisely what Lee wanted it to do. His commanders, especially A.P. Hill and Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell, were both exhausted, and Lt. Gen. James Longstreet was slightly ill, so Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson was replacing him. His inexperience at Corps command showed during the battle, but he performed to the best of his ability. Stonewall Jackson commanded the longest line with his Stonewall Brigade, and put forth his best efforts. The Confederates were exhausted but they fought with tenacity and inflicted heavy casualties on the Union soldiers. Jackson had them concentrate their fire along the line, decimating every attempt to approach along his line.

Without Stuart, Jackson couldn't flank as he had planned, to sweep the field, but he had Jubal Early take two brigades from his earthworks, under Doles and Battle, and come around to flank, along with Breckenridge and Pickett. They approached through the forest, using it as cover for their approach, and when they emerged, were able to destroy the brigades under McIvor, McKeen, and Owen. The men began running back in panic, causing chaos in the field, disrupting the efforts of Birney and Barlow against Jackson and Longstreet.

About 5:30 PM, Hancock told Meade their position was being turned on their left flank. Grant finally realized the situation he faced, and ordered his men to stop advancing and retreat back across the bridge. They made a fighting retreat on their left flank back across the river. That night, Grant and Meade argued again about the campaign, and Grant mollified Meade somewhat by ordering Burnside's IX Corps to report to him, rather than Grant. Though Burnside was a senior major general to Meade, he accepted the new subordinate position without protest.

The next day, there was some light skirmishing, but nothing major. Grant would be reluctant still to attack strong defensive lines, and would try to turn Lee's flank again, and meet his army soon at Cold Harbor.

Command

-US: Ulysses S Grant, George Meade

-CS: Robert E Lee

Army

-US: Army of the Potomac, IX Corps; 67,000-94,034

-CS: Army of Northern Virginia; 56,811

Casualties

-US: 4,455; (765 killed; 2,988 wounded; 702 captured/missing)

-CS: 1,427; (101 killed; 644 wounded; 682 captured/missing)

Battle of Fort Merced (May 28)

Named for the Merced River, the Union forces had built a fort nearby to guard the pass up towards the capital of North California. Col. Tomas Avila Sanchez, and Lt. Col. Roberto Perez with their brigade under Brig. Gen. J.P. Gillis marched with 4,000 men, along with another 4,000 under Brig. Gen. Dan Showalter. They had 8 horse artillery each, though they had poor reconnaissance done of the Fort, not knowing its defenses, because of the cavalry there blocking their own reconnaissance.

Showalter decided to attack the morning of the 28th, launching his artillery first for surprise at 4:30 AM, concentrating his fire to try to destroy the fort's walls. The wooden walls collapsed along the southern face, while his cavalry were riding and shooting, trying to pick off the defenders. The Union efforts were panicked at first, but by about 5:45 AM the Union managed to mount somewhat of a defense. By 6:30, the tides had turned, and the Union forces and their cavalry were turning the tide out in the open, pushing back Showalter's cavalry. Lt. Col. Marco Zapatero helped the cavalry retreat, while Gillis ordered the retreat after four hours of fierce fighting.

The Confederates suffered 480 casualties to the 360 casualties by the Union defenders. Gillis would send his troops south of the California border for rest and refit before trying again.

Baltimore, Maryland (June 7-8)

In Maryland, the Republicans hold their convention in Baltimore, under the name of the National Union party, to help War Democrats support the party. The Republicans renominated Lincoln, but switched Vice-Presidents to Andrew Johnson, currently serving as military governor of Tennessee.

Upon hearing of his re-nomination, Lincoln wrote:

"I have not permitted myself, gentlemen, to conclude that I am the best man in the country; but I am reminded, in this connection, of a story of an old Dutch farmer, who remarked to a companion once that "it was not best to swap horses when crossing streams.""

There was a lot of back-room dealing involved in getting the nomination again, specifically the promise to name Simon Cameron to the cabinet if he were re-elected, to help shore up support in Pennsylvania.

During the convention, Radical Republicans, a hard-line faction within Lincoln's own party, whom some blamed for the South's secession, believed Lincoln incompetent and that he shouldn't be re-elected, and formed a splinter party, the Radical Democracy Party, which met over in Cleveland, Ohio on the 31st of May. They nominated John C Frémont, the old 1856 Republican nominee. They did this hoping someone else other than Lincoln would get the nomination.

Republicans loyal to Lincoln and the party created a new name for the party, the National Union Party, to accommodate the war Democrats who supported the war, and wanted to separate themselves from what some derisively called "Copperheads." The convention dropped the Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, a Radical Republican, from the ticket, and replaced him with War Democrat Andrew Johnson, hoping that would stress the national character of the war and attract more voters.

During the convention, the party created a platform of 11 resolutions:

1. Integrity of the Union, quelling the Rebellion, and punishing the rebels and traitors

2. No compromise with the Rebels, no peace but unconditional surrender and return to the Union: "in full reliance upon the self-sacrificing patriotism, the heroic valor and the undying devotion of the American people to their country and its free institutions."

3. Slavery is the cause and strength of the Rebellion and must be destroyed. The Rebels now arm slaves and will return them to the fields if their rebellion succeeds.

4. The nation owes the soldiers and sailors thanks and "permanent recognition of their patriotism and their valor"

5. Approval of the "practical wisdom, the unselfish patriotism, and the unswerving fidelity to the Constitution and the principles of American liberty, with which Abraham Lincoln has discharged" as well as approval of the Gettysburg Proclamation and enlisting former slaves into the army

6. Only those approving of these resolutions will serve in public office

7. The Government will protect the troops from any violation of the laws by the Rebels

8. Foreign immigration should be fostered and encouraged.

9. Speedy construction of a railroad to the Pacific coast.

10. Keeping the faith and redemption of public debt, just taxation, and loyal states will promote the credit and national currency of the United States.

11. The US will not ignore any European power attempting to overthrow any republican government in the western hemisphere near the US.

Each of these was met with applause of the crowd.

Battle of Cold Harbor (June 8-24)

Battle of Cold Harbor, Smithsonian War Between the States Exhibit

June 7

Both Union and Confederate cavalry continued sparring each other as they had at Old Church. Lee sent a division under Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee to reinforce Brig. Gen. Matthew Butler, and secure the crossroads at Old Cold Harbor. He kept Stuart close as his own cavalry screen. As Union Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert, now in charge of the Union cavalry corps tried to increase pressure on the Confederates, Lee had Longstreet's Corps shift right from Totopotomoy Creek to support the cavalry. About 4 PM, though, Torbert drove the Confederates from the crossroads of Old Cold Harbor and began digging in. As more of the Confederates arrived, the Union cavalry commander Torbert got concerned and pulled back towards Old Church.

Grant decided to make his stand at Old Cold Harbor and ordered Torbert to hold it "at all hazards." He sent Wright's VI Corps to move in that direction.

June 8

First day of battle on the 8th

Lee's plan for the 8th was to use his partly reinforced infantry, with a small trickle of the new black troops filling in for casualties as they happened, against the small cavalry forces at Old Cold Harbor. The Confederates, rather than segregating their black troops, put them into existing white brigades so they could benefit from veterans and train up more quickly, within two to three months, as opposed to about a year for Union Colored Troops, who were segregated and didn't have the benefit of veterans to train them. The policy of integrating would also have repercussions politically, as the black troops would affect the old attitudes of their fellow soldiers about the place of black people in Confederate society, especially when a black soldier is the one covering your attack or retreat, or dragging your injured body from a field under fire. Lee also made sure discipline was kept between the black and white troopers, that troops were treated equally regarding provisions, rations, and so on.

Longstreet integrated Hoke's division into his attack plan, making sure he understood he was to attack with everyone else.

Wright's VI Corps didn't move out till after midnight, and was on a 15-mile march, and Smith's XVIII Corps had been mistakenly sent to New Castle Ferry on the Pamunkey River, several miles away, and didn't reach Old Cold Harbor in time to help Torbert.

Longstreet led his attack with the brigade under veteran Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw, who had taken on the task of ensuring his new colored troops, about 80, were as efficient as his white troops and drilled them when time permitted. Kershaw's men approached the entrenched cavalry of Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt. The Union men were armed with seven-shot Spencer repeating carbines, so they delivered heavy fire, mortally wounding Col. Laurence Keitt, but Kershaw managed to keep unit cohesion, and Hoke's participation kept up the Confederate assault, till they were recalled by Longstreet. The Union here suffered casualties slightly greater than the Confederates. But the armaments took their toll.

By 9 AM, Wright's lead elements arrived at the crossroads, and began extending and improving the Union entrenchments. Though Grant originally intended Wright to attack immediately, they were exhausted from their march, and were unsure of Confederate strength. Wright waited till Smith arrived in the afternoon, and the XVIII Corps began entrenching to the right of VI Corps. Union cavalry moved east to retire.

For the upcoming attack, Meade was concerned that Wright and Smith's corps wouldn't be enough and tried to convince Warren to send reinforcements. He wrote to him, and Warren sent a division under Brig. Gen. Henry Lockwood, which began marching at 6 PM. Without adequate reconnaissance of the road, he couldn't reach the battle in enough time to make a difference. Meade was also concerned about his left flank, which wasn't anchored on the Chickahominy and was potentially threatened by Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry. He ordered Torbert to send scouting parties there, but Torbert resisted, telling Meade he couldn't move his men before dark.

It took till 6:30 PM, but the attack Grant had ordered to happen that morning finally began. Both Wright's and Smith's corps moved forward. Wright's men made little progress, recoiling from heavy fire south of Mechanicsville Road. North of that road, Brig. Gen. Emory Upton's brigade faced heavy fire from Confederate Brig. Gen. Thomas Clingman's brigade, later quoted as "A sheet of flame, sudden as lightning, red as blood, and so near that it seemed to singe the men's faces." Though Upton tried valiantly to rally his men forward, they fell back to their starting point.

To the right of Upton, Col. William Truex's brigade found a gap in the Confederates' line, between Clingman and Wofford's brigades, through a swampy, brush-filled ravine. As Truex sent his men charging into the gap, Clingman swung two regiments around to face them, and Longstreet sent Brig. Gen. Eppa Hunton's brigade from his reserves. Truex was then surrounded on 3 sides, and was forced to withdraw, without anything to show for it but casualties*.

*Change: No Georgians as prisoners

While the southern end of the lines of battle was active, the three corps of Hancock, Burnside, and Warren were occupying a 5-mile line stretching southeast to Bethesda Church, facing the Confederates under Ewell, Breckinridge, and Early. At the border between the IX and V Corps, the division of Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden, newly arrived after his poor performance at Chickamauga, occupied a doglegged position (looking like an L pointing north) with the long face on Shady Grove Road, separated from V Corps by a march called Magnolia Swamp. Two divisions of Early's Corps would use this as their avenue of approach, but despite the poor battle management of Crittenden, the Confederate probes would be repulsed.

At this time, Warren's division under Lockwood got lost wandering around on unfamiliar farm roads. Despite having dispatched Lockwood explicitly the V Corps commander wrote Meade, "In some unaccountable way, [Lockwood] took his whole division, without my knowing it, away from the left of the line of battle, and turned up the dark 2 miles in my rear, and I have not yet got him back. All this time the firing should have guided him at least. He is too incompetent, and too high rank leaves us no subordinate place for him. I earnestly beg that he may at once be relieved of duty with this army." In response Meade relieved Lockwood and replaced him with Brig. Gen. Samuel Crawford.

By sunset, fighting had petered out on both ends of the line. The Union had suffered 2400 casualties to 800 Confederate casualties, but some progress had been made - they had almost broken the Confederate line, which was now pinned into place with Union entrenchments being dug yards away. Several Union generals were furious at Grant for ordering an assault without proper reconnaissance.

June 9

Makeshift Confederate breastworks shown after the battle

Though the attacks of June 8th had been unsuccessful, Meade believed an attack early enough on the 9th would be successful if he could get sufficient force on an appropriate location. He and Grant decided to attack Lee's right flank. Longstreet's men had been heavily engaged there yesterday, and it was unlikely they'd found enough time to build stronger defenses. If the attack were successful, Lee's right could be driven back to the Chickahominy River.

Meade ordered Hancock's II Corps to shift southeast from the Totopotomoy Creek, and assume position left of Wright's VI Corps. Once in position, Meade planned to attack on his left with 3 Corps in line, 35,000 men in total (II Corps (Hancock), VI Corps (Wright), and XVIII Corps (Baldy Smith)). Meade also ordered Warren and Burnside to attack Lee's left flank in the morning "at all hazards."

It was a great plan, but Hancock's men had been marching almost all night, and were too worn out when they arrived for an immediate attack in the morning. Grant agreed to let them rest, and postponed the attack till 5 PM, then again till 4:30 AM on the 11th. Unfortunately Grant and Meade didn't give specific orders for the attack, leaving up to the corps commanders to decide where to strike and how they would coordinate with each other. No senior commander had reconnoitered the Confederate positions; Baldy Smith would write that he was "aghast at the reception of such an order, which proved conclusively the utter absence of any military plan." He told his staff that the whole attack was, "simply an order to slaughter my best troops."

On the Confederate side, they took advantage of Union delays to bolster their defenses and add obstacles to slow the Union troops. When Hancock had left, Lee shifted Breckinridge's division to the far right flank, to face Hancock again. Breckinridge drove a small Union force from Turkey Hill, which dominated the southern portion of the battlefield. Lee moved Mahone and Wilcox's divisions to support him, and Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry to guard the right flank; this made a 7-mile curving line on low ridges, making flanking impossible.

Later historians would write that Lee's engineers had built "the most ingenious defensive configuration the war had yet witnessed" with barricades of earth and log, artillery posted with converging fields of fire at every avenue of approach, and stakes being driven into the ground to aid gunners' range estimates. One reporter from the Richmond Examiner called it a "maze and labyrinth of works within works," with heavy skirmish lines to suppress the Union's ability to determine the strength or exact positions of the Confederate entrenchments. Lee gained another 3000 black troops, further bolstering his strength while Grant waited.

While they didn't know the details of their objectives, one of Grant's aides, Lt Col Horace Porter wrote in his memoirs that the soldiers knew what they would be facing. Many would be writing their names on papers pinned inside their uniforms. Burnside was advised to attack Early's unprotected flank, but he delayed.

June 10

Battle on the 10th of June

(OOC: replace Anderson with Longstreet, Hill with Ewell)

At 4:30 AM on the 10th, three Union corps began to advance through a thick ground fog. Massive return fire from the Confederate lines caused heavy casualties very quickly, and the survivors were pinned down. Though the results varied across the line, the overall repulse of the Union advance resulted in the most lopsided casualties since the Battle of Fredericksburg. Some of the most effective fire came from the new Confederate black troops, earning them the ire of the Union troops, many of whom believed they were there to free them, and they should be thanking them; they earned the respect of their fellow Confederates, which would help their efforts at civil rights after the war.

The most effective performance of the day turned out to be Hancock's corps on the Union left flank, which broke through a portion of Breckinridge's front line, and drove them out of their entrenchments in hand-to-hand fighting. The Union caught 4 guns and several hundred prisoners.

Unfortunately for the blue-clad warriors, nearby Confederate artillery was brought to bear on the entrenchments, turning them into a death trap for the Billy Yanks. Breckinridge's reserves counterattacked and drove off the Union troops. Hancock's other advance division, under Brig. Gen. John Gibbon got disordered in the swampy ground, and couldn't advance through the heavy fire, losing two brigade commanders (Cols. Peter Porter and H. Boyd McKeen) in the fighting. One of Gibbon's men, who complained about the lack of reconnaissance, wrote, "We felt it was murder, not war, or at best a very serious mistake had been made."

In the center, Wright's corps was pinned down by heavy fire, and could make little effort to advance, as they were still trying to recover from the action two days prior. Emory Upton, normally aggressive, felt further movement by his division, was "impracticable." Confederate defenders on this part of the line were unaware a serious assault had been made against them.

On the Union right, Smith's men advanced through unfavorable terrain, and were channeled into two ravines. When they emerged in front of the Confederate line, rifle and artillery fire mowed them down. One Union officer wrote, "The men bent down as they pushed forward, as if trying, as they were, to breast a tempest, and the files of men went down like rows of blocks or bricks pushed over by striking against one another."

On the Confederate side, one described the carnage of double-canister artillery fire as "deadly, bloody work." The artillery fire set against Smith's corps was heavier than might have been expected, as Warren's V Corps to Smith's right was reluctant to advance, so the Confederate gunners in that sector concentrated on Smith's men instead. It was here the Union first saw black Confederate artillery men, one of which, John Parker aimed the barrel right at Brig. Gen. John Martindale, cutting him in half when it fired.

On the northern side of the field, the only activity was Burnside's IX Corps facing Jubal Early, reinforced by Stonewall Jackson. Burnside launched a powerful assault at 6 AM, but the Confederates found his corps halted in the first line of earthworks and brought heavy fire down on them, forcing them to retreat as well.

At 7 AM, Grant advised Meade to exploit vigorously, any successful part of the assault. Meade ordered his three corps commanders on the left to assault at once, without regard to the movements of their neighboring corps. Unfortunately all of then had had enough of the fight. Hancock advised against it; Smith called it a "wanton waste of life," and refused to advance again. Wright's men increased their rifle fire, but stayed in place. By 12:30 PM, Grant conceded his army was done.

He wrote to Meade, "The opinion of the corps commanders not being sanguine of success in case an assault is ordered, you may direct a suspension of further advance for the present." The Union soldiers still pinned down in front of Confederate lines began entrenching, using cups and bayonets to dig, sometimes including the bodies of their dead comrades in their improvised earthworks.

The next day, Meade bragged to his wife that he was in command for the assault, but his own performance in the fight had been poor. Despite orders from Grant for the corps commanders to examine the ground, their reconnaissance had been lax, and Meade didn't supervise them adequately, either before or during the attack.

Meade was only able to motivate about 20,000 of his men to attack, the II Corps, along with parts of the IX and XVIII, which meant he failed to achieve the mass he knew he would require to succeed. His men paid for the poorly coordinated assault with casualties between 4,000-8,000, with no more than 1,500 on the Confederate side.

Grant would later write in his memoirs:

"I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. I might say the same thing of the assault of the 22d of May, 1863, at Vicksburg. At Cold Harbor no advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained. Indeed, the advantages other than those of relative losses, were on the Confederate side. Before that, the Army of Northern Virginia seemed to have acquired a wholesome regard for the courage, endurance, and soldierly qualities generally of the Army of the Potomac. They no longer wanted to fight them "one Confederate to five Yanks." Indeed, they seemed to have given up any idea of gaining any advantage of their antagonist in the open field. They had come to much prefer breastworks in their front to the Army of the Potomac. This charge seemed to revive their hopes temporarily; but it was of short duration. The effect upon the Army of the Potomac was the reverse. When we reached the James River, however, all effects of the battle of Cold Harbor seemed to have disappeared."

At 11 AM on the 10th, Confederate Postmaster General, John Reagan, arrived with a delegation from Richmond. He asked Lee, "General, if the enemy breaks your line, what reserve have you?" Lee replied, "Not a regiment, which has been my condition ever since fighting has commenced on the Rappahannock. If I shorten my lines to provide a reserve, he will turn me; if I weaken my lines to provide a reserve he will break them. The Congress have emancipated bondservants. Now we need them trained, supplied, and provided if we are to win our independence." Modern scholars have shown Lee to have had ample reserves unengaged. His comments were likely to persuade the War Department to send more troops.

June 12-20

Both sides did not launch any further assaults, but engaged in trench warfare facing each other for the next nine days, some places only yards apart. Sharpshooters worked continuously, killing many. Union artillery bombarded the Confederates with a battery of 8 Coehorn mortars; the Confederates responded by depressing the trail of a 24-lb howitzer and lobbing shells over the Union positions. Though there were no more large-scale assaults, the casualties for the whole battle were twice as large as that from just the assault on the 10th alone.

The trenches were miserable, but conditions were worse between the lines, where thousands of wounded Union troops suffered horribly in the hot conditions without food, water, or medical help. Grant was reluctant to ask for a formal truce to recover them, because that would be acknowledging he lost the battle. Lee and Grant traded notes from the 12th-14th across the lines without coming to an agreement, when Grant finally requested a two-hour cessation of hostilities, but it was too late for most of the wounded, who were now just bloated corpses. He would be widely criticized for this lapse of judgment in the Northern press.

Command

-US: Ulysses Grant, George Meade

-CS: Robert E. Lee

Army

-US: Army of the Potomac (108,000-117,000)

-CS: Army of Northern Virginia (64,000)

Casualties

-US: 15,193; (2,655 killed; 10,347 wounded; 2,191 captured/missing)

-CS: 4,703; (691 killed; 3,109 wounded; 903 captured/missing)

Notable Casualties

-US: Brig Gen John Martindale*

-CS:

After Grant disengaged from the stalemate over at Spotsylvania Court House, he tried to lure Lee into a battle with Burnside, but he didn't fall for it. He lost the race to Lee's next defensive position, south of the North Anna River. Lee was unsure of Grant's intentions, but Jackson believed he was going to attack and urged his commander to build defensive works.

They devised a scheme of an inverted "V" to try to split the Union army when it advanced, and allow the Confederates to use interior lines to attack and defeat one wing, and prevent the other wing from reinforcing it in time. Surprisingly, Warren's V Corps missed Lee's army marching south right next to it.

Battle on the 28th

On the morning of the 28th, Grant sent additional troops south of the North Anna River. Wright's VI Corps crossed at Jericho Mills, and by 11 AM both Warren and Wright advanced to the Virginia Central Railroad. At 8 AM, Hancock's II Corps finally crossed the Chesterfield Bridge, with the 2nd US Sharpshooters and 20th Indiana dashing across the bridge to try to disperse a thin Confederate picket line. Down the river, the confederates had burned away the rail bridge, but soldiers from the 8th Ohio cut down a large tree so the men could cross single-file. The Union troops soon got a pontoon bridge set up and all of Maj. Gen. John Gibbon's division crossed. This is when Grant began to fall into Lee's trap. Seeing how easy it was to cross the river, he assumed the Confederates to be retreating. He wired command back in Washington: "The enemy have fallen back from North Anna. We are in pursuit."

The only visible opposition to their crossing was at Ox Ford, which Grant saw as simply a rear guard action, just an annoyance. So Grant ordered Burnside's IX Corps to deal with hit. Burnside had Brig. Gen. Samuel Crawford march upriver to Quarles Mill and seize the the ford there. Burnside ordered Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden's division to cross there at the ford, and follow the river's southern bank to Ox Ford, and attack the Confederate positions from the west.

Crittenden's lead brigade was unfortunately led by Brig. Gen. James Ledlie, known for his excessive consumption of alcohol in the field. Being intoxicated and ambitious, Ledlie decided to attack the Confederate position alone with just his brigade. His brigade encountered the Confederate earthworks, manned by Brig. Gen. William Mahone's division. Ledlie sent his 35th Massachusetts forward, but were immediately repulsed. Then he sent an officer back to ask for three more regiments from Crittenden as reinforcements. The division commander was surprised and had the officer instruct Ledlie not to attack till the full division crossed over.

Unfortunately by that time, Ledlie was completely drunk. When several Confederate artillery batteries on the earthworks were pointed out to him, he dismissed them and ordered a charge. His men started as a rain began to fall, and in their rush to get to the enemy's earthworks, the regiments got mixed up and confused. The Confederates waited to fire till they got close, which drove them into ditches for protection. A violent thunderstorm erupted, and though the 56th and 57th Massachusetts regiments tried to rally, Mahone's Mississippi troops stepped out of their earthworks and shot them down.

Col. Stephen Weld (56th MA) was wounded, and Lt. Col. Charles Chandler (57th MA) was mortally wounded. Soon all of Ledlie's men had to retreat, and they made it back to Quarles Mill. Despite his utterly miserable performance, Ledlie got praise from his division commander, saying his brigade "behaved gallantly." Ledlie was promoted to division command after this battle, and his drunkenness would continue to plague his men.

Hancock's II Corps began pushing south from Chesterfield Bridge about the same time Ledlie was just crossing over. Hancock ordered Gibbon's division to advance down the railroad. They pushed aside some Confederate skirmishers, but then ran into the earthworks, and most of his division was engaged. The fighting was interrupted by the thunderstorm, since men on both sides were worried it would ruin their gunpowder. As the rain slacked off, Maj. Gen. David Birney's division came to Gibbon's aid, but even both at once couldn't break the Confederate line.

The Union army was doing precisely what Lee wanted it to do. His commanders, especially A.P. Hill and Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell, were both exhausted, and Lt. Gen. James Longstreet was slightly ill, so Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson was replacing him. His inexperience at Corps command showed during the battle, but he performed to the best of his ability. Stonewall Jackson commanded the longest line with his Stonewall Brigade, and put forth his best efforts. The Confederates were exhausted but they fought with tenacity and inflicted heavy casualties on the Union soldiers. Jackson had them concentrate their fire along the line, decimating every attempt to approach along his line.

Without Stuart, Jackson couldn't flank as he had planned, to sweep the field, but he had Jubal Early take two brigades from his earthworks, under Doles and Battle, and come around to flank, along with Breckenridge and Pickett. They approached through the forest, using it as cover for their approach, and when they emerged, were able to destroy the brigades under McIvor, McKeen, and Owen. The men began running back in panic, causing chaos in the field, disrupting the efforts of Birney and Barlow against Jackson and Longstreet.

About 5:30 PM, Hancock told Meade their position was being turned on their left flank. Grant finally realized the situation he faced, and ordered his men to stop advancing and retreat back across the bridge. They made a fighting retreat on their left flank back across the river. That night, Grant and Meade argued again about the campaign, and Grant mollified Meade somewhat by ordering Burnside's IX Corps to report to him, rather than Grant. Though Burnside was a senior major general to Meade, he accepted the new subordinate position without protest.

The next day, there was some light skirmishing, but nothing major. Grant would be reluctant still to attack strong defensive lines, and would try to turn Lee's flank again, and meet his army soon at Cold Harbor.

Command

-US: Ulysses S Grant, George Meade

-CS: Robert E Lee

Army

-US: Army of the Potomac, IX Corps; 67,000-94,034

-CS: Army of Northern Virginia; 56,811

Casualties

-US: 4,455; (765 killed; 2,988 wounded; 702 captured/missing)

-CS: 1,427; (101 killed; 644 wounded; 682 captured/missing)

Battle of Fort Merced (May 28)

Named for the Merced River, the Union forces had built a fort nearby to guard the pass up towards the capital of North California. Col. Tomas Avila Sanchez, and Lt. Col. Roberto Perez with their brigade under Brig. Gen. J.P. Gillis marched with 4,000 men, along with another 4,000 under Brig. Gen. Dan Showalter. They had 8 horse artillery each, though they had poor reconnaissance done of the Fort, not knowing its defenses, because of the cavalry there blocking their own reconnaissance.

Showalter decided to attack the morning of the 28th, launching his artillery first for surprise at 4:30 AM, concentrating his fire to try to destroy the fort's walls. The wooden walls collapsed along the southern face, while his cavalry were riding and shooting, trying to pick off the defenders. The Union efforts were panicked at first, but by about 5:45 AM the Union managed to mount somewhat of a defense. By 6:30, the tides had turned, and the Union forces and their cavalry were turning the tide out in the open, pushing back Showalter's cavalry. Lt. Col. Marco Zapatero helped the cavalry retreat, while Gillis ordered the retreat after four hours of fierce fighting.

The Confederates suffered 480 casualties to the 360 casualties by the Union defenders. Gillis would send his troops south of the California border for rest and refit before trying again.

Baltimore, Maryland (June 7-8)

In Maryland, the Republicans hold their convention in Baltimore, under the name of the National Union party, to help War Democrats support the party. The Republicans renominated Lincoln, but switched Vice-Presidents to Andrew Johnson, currently serving as military governor of Tennessee.

Upon hearing of his re-nomination, Lincoln wrote:

"I have not permitted myself, gentlemen, to conclude that I am the best man in the country; but I am reminded, in this connection, of a story of an old Dutch farmer, who remarked to a companion once that "it was not best to swap horses when crossing streams.""

There was a lot of back-room dealing involved in getting the nomination again, specifically the promise to name Simon Cameron to the cabinet if he were re-elected, to help shore up support in Pennsylvania.

During the convention, Radical Republicans, a hard-line faction within Lincoln's own party, whom some blamed for the South's secession, believed Lincoln incompetent and that he shouldn't be re-elected, and formed a splinter party, the Radical Democracy Party, which met over in Cleveland, Ohio on the 31st of May. They nominated John C Frémont, the old 1856 Republican nominee. They did this hoping someone else other than Lincoln would get the nomination.

Republicans loyal to Lincoln and the party created a new name for the party, the National Union Party, to accommodate the war Democrats who supported the war, and wanted to separate themselves from what some derisively called "Copperheads." The convention dropped the Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, a Radical Republican, from the ticket, and replaced him with War Democrat Andrew Johnson, hoping that would stress the national character of the war and attract more voters.

During the convention, the party created a platform of 11 resolutions:

1. Integrity of the Union, quelling the Rebellion, and punishing the rebels and traitors

2. No compromise with the Rebels, no peace but unconditional surrender and return to the Union: "in full reliance upon the self-sacrificing patriotism, the heroic valor and the undying devotion of the American people to their country and its free institutions."

3. Slavery is the cause and strength of the Rebellion and must be destroyed. The Rebels now arm slaves and will return them to the fields if their rebellion succeeds.

4. The nation owes the soldiers and sailors thanks and "permanent recognition of their patriotism and their valor"

5. Approval of the "practical wisdom, the unselfish patriotism, and the unswerving fidelity to the Constitution and the principles of American liberty, with which Abraham Lincoln has discharged" as well as approval of the Gettysburg Proclamation and enlisting former slaves into the army

6. Only those approving of these resolutions will serve in public office

7. The Government will protect the troops from any violation of the laws by the Rebels

8. Foreign immigration should be fostered and encouraged.

9. Speedy construction of a railroad to the Pacific coast.

10. Keeping the faith and redemption of public debt, just taxation, and loyal states will promote the credit and national currency of the United States.

11. The US will not ignore any European power attempting to overthrow any republican government in the western hemisphere near the US.

Each of these was met with applause of the crowd.

Battle of Cold Harbor (June 8-24)

Battle of Cold Harbor, Smithsonian War Between the States Exhibit

June 7

Both Union and Confederate cavalry continued sparring each other as they had at Old Church. Lee sent a division under Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee to reinforce Brig. Gen. Matthew Butler, and secure the crossroads at Old Cold Harbor. He kept Stuart close as his own cavalry screen. As Union Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbert, now in charge of the Union cavalry corps tried to increase pressure on the Confederates, Lee had Longstreet's Corps shift right from Totopotomoy Creek to support the cavalry. About 4 PM, though, Torbert drove the Confederates from the crossroads of Old Cold Harbor and began digging in. As more of the Confederates arrived, the Union cavalry commander Torbert got concerned and pulled back towards Old Church.

Grant decided to make his stand at Old Cold Harbor and ordered Torbert to hold it "at all hazards." He sent Wright's VI Corps to move in that direction.

June 8

First day of battle on the 8th

Lee's plan for the 8th was to use his partly reinforced infantry, with a small trickle of the new black troops filling in for casualties as they happened, against the small cavalry forces at Old Cold Harbor. The Confederates, rather than segregating their black troops, put them into existing white brigades so they could benefit from veterans and train up more quickly, within two to three months, as opposed to about a year for Union Colored Troops, who were segregated and didn't have the benefit of veterans to train them. The policy of integrating would also have repercussions politically, as the black troops would affect the old attitudes of their fellow soldiers about the place of black people in Confederate society, especially when a black soldier is the one covering your attack or retreat, or dragging your injured body from a field under fire. Lee also made sure discipline was kept between the black and white troopers, that troops were treated equally regarding provisions, rations, and so on.

Longstreet integrated Hoke's division into his attack plan, making sure he understood he was to attack with everyone else.

Wright's VI Corps didn't move out till after midnight, and was on a 15-mile march, and Smith's XVIII Corps had been mistakenly sent to New Castle Ferry on the Pamunkey River, several miles away, and didn't reach Old Cold Harbor in time to help Torbert.

Longstreet led his attack with the brigade under veteran Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw, who had taken on the task of ensuring his new colored troops, about 80, were as efficient as his white troops and drilled them when time permitted. Kershaw's men approached the entrenched cavalry of Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt. The Union men were armed with seven-shot Spencer repeating carbines, so they delivered heavy fire, mortally wounding Col. Laurence Keitt, but Kershaw managed to keep unit cohesion, and Hoke's participation kept up the Confederate assault, till they were recalled by Longstreet. The Union here suffered casualties slightly greater than the Confederates. But the armaments took their toll.

By 9 AM, Wright's lead elements arrived at the crossroads, and began extending and improving the Union entrenchments. Though Grant originally intended Wright to attack immediately, they were exhausted from their march, and were unsure of Confederate strength. Wright waited till Smith arrived in the afternoon, and the XVIII Corps began entrenching to the right of VI Corps. Union cavalry moved east to retire.

For the upcoming attack, Meade was concerned that Wright and Smith's corps wouldn't be enough and tried to convince Warren to send reinforcements. He wrote to him, and Warren sent a division under Brig. Gen. Henry Lockwood, which began marching at 6 PM. Without adequate reconnaissance of the road, he couldn't reach the battle in enough time to make a difference. Meade was also concerned about his left flank, which wasn't anchored on the Chickahominy and was potentially threatened by Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry. He ordered Torbert to send scouting parties there, but Torbert resisted, telling Meade he couldn't move his men before dark.

It took till 6:30 PM, but the attack Grant had ordered to happen that morning finally began. Both Wright's and Smith's corps moved forward. Wright's men made little progress, recoiling from heavy fire south of Mechanicsville Road. North of that road, Brig. Gen. Emory Upton's brigade faced heavy fire from Confederate Brig. Gen. Thomas Clingman's brigade, later quoted as "A sheet of flame, sudden as lightning, red as blood, and so near that it seemed to singe the men's faces." Though Upton tried valiantly to rally his men forward, they fell back to their starting point.

To the right of Upton, Col. William Truex's brigade found a gap in the Confederates' line, between Clingman and Wofford's brigades, through a swampy, brush-filled ravine. As Truex sent his men charging into the gap, Clingman swung two regiments around to face them, and Longstreet sent Brig. Gen. Eppa Hunton's brigade from his reserves. Truex was then surrounded on 3 sides, and was forced to withdraw, without anything to show for it but casualties*.

*Change: No Georgians as prisoners

While the southern end of the lines of battle was active, the three corps of Hancock, Burnside, and Warren were occupying a 5-mile line stretching southeast to Bethesda Church, facing the Confederates under Ewell, Breckinridge, and Early. At the border between the IX and V Corps, the division of Maj. Gen. Thomas Crittenden, newly arrived after his poor performance at Chickamauga, occupied a doglegged position (looking like an L pointing north) with the long face on Shady Grove Road, separated from V Corps by a march called Magnolia Swamp. Two divisions of Early's Corps would use this as their avenue of approach, but despite the poor battle management of Crittenden, the Confederate probes would be repulsed.

At this time, Warren's division under Lockwood got lost wandering around on unfamiliar farm roads. Despite having dispatched Lockwood explicitly the V Corps commander wrote Meade, "In some unaccountable way, [Lockwood] took his whole division, without my knowing it, away from the left of the line of battle, and turned up the dark 2 miles in my rear, and I have not yet got him back. All this time the firing should have guided him at least. He is too incompetent, and too high rank leaves us no subordinate place for him. I earnestly beg that he may at once be relieved of duty with this army." In response Meade relieved Lockwood and replaced him with Brig. Gen. Samuel Crawford.

By sunset, fighting had petered out on both ends of the line. The Union had suffered 2400 casualties to 800 Confederate casualties, but some progress had been made - they had almost broken the Confederate line, which was now pinned into place with Union entrenchments being dug yards away. Several Union generals were furious at Grant for ordering an assault without proper reconnaissance.

June 9

Makeshift Confederate breastworks shown after the battle

Though the attacks of June 8th had been unsuccessful, Meade believed an attack early enough on the 9th would be successful if he could get sufficient force on an appropriate location. He and Grant decided to attack Lee's right flank. Longstreet's men had been heavily engaged there yesterday, and it was unlikely they'd found enough time to build stronger defenses. If the attack were successful, Lee's right could be driven back to the Chickahominy River.

Meade ordered Hancock's II Corps to shift southeast from the Totopotomoy Creek, and assume position left of Wright's VI Corps. Once in position, Meade planned to attack on his left with 3 Corps in line, 35,000 men in total (II Corps (Hancock), VI Corps (Wright), and XVIII Corps (Baldy Smith)). Meade also ordered Warren and Burnside to attack Lee's left flank in the morning "at all hazards."

It was a great plan, but Hancock's men had been marching almost all night, and were too worn out when they arrived for an immediate attack in the morning. Grant agreed to let them rest, and postponed the attack till 5 PM, then again till 4:30 AM on the 11th. Unfortunately Grant and Meade didn't give specific orders for the attack, leaving up to the corps commanders to decide where to strike and how they would coordinate with each other. No senior commander had reconnoitered the Confederate positions; Baldy Smith would write that he was "aghast at the reception of such an order, which proved conclusively the utter absence of any military plan." He told his staff that the whole attack was, "simply an order to slaughter my best troops."

On the Confederate side, they took advantage of Union delays to bolster their defenses and add obstacles to slow the Union troops. When Hancock had left, Lee shifted Breckinridge's division to the far right flank, to face Hancock again. Breckinridge drove a small Union force from Turkey Hill, which dominated the southern portion of the battlefield. Lee moved Mahone and Wilcox's divisions to support him, and Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry to guard the right flank; this made a 7-mile curving line on low ridges, making flanking impossible.

Later historians would write that Lee's engineers had built "the most ingenious defensive configuration the war had yet witnessed" with barricades of earth and log, artillery posted with converging fields of fire at every avenue of approach, and stakes being driven into the ground to aid gunners' range estimates. One reporter from the Richmond Examiner called it a "maze and labyrinth of works within works," with heavy skirmish lines to suppress the Union's ability to determine the strength or exact positions of the Confederate entrenchments. Lee gained another 3000 black troops, further bolstering his strength while Grant waited.

While they didn't know the details of their objectives, one of Grant's aides, Lt Col Horace Porter wrote in his memoirs that the soldiers knew what they would be facing. Many would be writing their names on papers pinned inside their uniforms. Burnside was advised to attack Early's unprotected flank, but he delayed.

June 10

Battle on the 10th of June

(OOC: replace Anderson with Longstreet, Hill with Ewell)

At 4:30 AM on the 10th, three Union corps began to advance through a thick ground fog. Massive return fire from the Confederate lines caused heavy casualties very quickly, and the survivors were pinned down. Though the results varied across the line, the overall repulse of the Union advance resulted in the most lopsided casualties since the Battle of Fredericksburg. Some of the most effective fire came from the new Confederate black troops, earning them the ire of the Union troops, many of whom believed they were there to free them, and they should be thanking them; they earned the respect of their fellow Confederates, which would help their efforts at civil rights after the war.

The most effective performance of the day turned out to be Hancock's corps on the Union left flank, which broke through a portion of Breckinridge's front line, and drove them out of their entrenchments in hand-to-hand fighting. The Union caught 4 guns and several hundred prisoners.

Unfortunately for the blue-clad warriors, nearby Confederate artillery was brought to bear on the entrenchments, turning them into a death trap for the Billy Yanks. Breckinridge's reserves counterattacked and drove off the Union troops. Hancock's other advance division, under Brig. Gen. John Gibbon got disordered in the swampy ground, and couldn't advance through the heavy fire, losing two brigade commanders (Cols. Peter Porter and H. Boyd McKeen) in the fighting. One of Gibbon's men, who complained about the lack of reconnaissance, wrote, "We felt it was murder, not war, or at best a very serious mistake had been made."

In the center, Wright's corps was pinned down by heavy fire, and could make little effort to advance, as they were still trying to recover from the action two days prior. Emory Upton, normally aggressive, felt further movement by his division, was "impracticable." Confederate defenders on this part of the line were unaware a serious assault had been made against them.

On the Union right, Smith's men advanced through unfavorable terrain, and were channeled into two ravines. When they emerged in front of the Confederate line, rifle and artillery fire mowed them down. One Union officer wrote, "The men bent down as they pushed forward, as if trying, as they were, to breast a tempest, and the files of men went down like rows of blocks or bricks pushed over by striking against one another."

On the Confederate side, one described the carnage of double-canister artillery fire as "deadly, bloody work." The artillery fire set against Smith's corps was heavier than might have been expected, as Warren's V Corps to Smith's right was reluctant to advance, so the Confederate gunners in that sector concentrated on Smith's men instead. It was here the Union first saw black Confederate artillery men, one of which, John Parker aimed the barrel right at Brig. Gen. John Martindale, cutting him in half when it fired.

On the northern side of the field, the only activity was Burnside's IX Corps facing Jubal Early, reinforced by Stonewall Jackson. Burnside launched a powerful assault at 6 AM, but the Confederates found his corps halted in the first line of earthworks and brought heavy fire down on them, forcing them to retreat as well.

At 7 AM, Grant advised Meade to exploit vigorously, any successful part of the assault. Meade ordered his three corps commanders on the left to assault at once, without regard to the movements of their neighboring corps. Unfortunately all of then had had enough of the fight. Hancock advised against it; Smith called it a "wanton waste of life," and refused to advance again. Wright's men increased their rifle fire, but stayed in place. By 12:30 PM, Grant conceded his army was done.

He wrote to Meade, "The opinion of the corps commanders not being sanguine of success in case an assault is ordered, you may direct a suspension of further advance for the present." The Union soldiers still pinned down in front of Confederate lines began entrenching, using cups and bayonets to dig, sometimes including the bodies of their dead comrades in their improvised earthworks.

The next day, Meade bragged to his wife that he was in command for the assault, but his own performance in the fight had been poor. Despite orders from Grant for the corps commanders to examine the ground, their reconnaissance had been lax, and Meade didn't supervise them adequately, either before or during the attack.

Meade was only able to motivate about 20,000 of his men to attack, the II Corps, along with parts of the IX and XVIII, which meant he failed to achieve the mass he knew he would require to succeed. His men paid for the poorly coordinated assault with casualties between 4,000-8,000, with no more than 1,500 on the Confederate side.

Grant would later write in his memoirs:

"I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made. I might say the same thing of the assault of the 22d of May, 1863, at Vicksburg. At Cold Harbor no advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained. Indeed, the advantages other than those of relative losses, were on the Confederate side. Before that, the Army of Northern Virginia seemed to have acquired a wholesome regard for the courage, endurance, and soldierly qualities generally of the Army of the Potomac. They no longer wanted to fight them "one Confederate to five Yanks." Indeed, they seemed to have given up any idea of gaining any advantage of their antagonist in the open field. They had come to much prefer breastworks in their front to the Army of the Potomac. This charge seemed to revive their hopes temporarily; but it was of short duration. The effect upon the Army of the Potomac was the reverse. When we reached the James River, however, all effects of the battle of Cold Harbor seemed to have disappeared."

At 11 AM on the 10th, Confederate Postmaster General, John Reagan, arrived with a delegation from Richmond. He asked Lee, "General, if the enemy breaks your line, what reserve have you?" Lee replied, "Not a regiment, which has been my condition ever since fighting has commenced on the Rappahannock. If I shorten my lines to provide a reserve, he will turn me; if I weaken my lines to provide a reserve he will break them. The Congress have emancipated bondservants. Now we need them trained, supplied, and provided if we are to win our independence." Modern scholars have shown Lee to have had ample reserves unengaged. His comments were likely to persuade the War Department to send more troops.

June 12-20

Both sides did not launch any further assaults, but engaged in trench warfare facing each other for the next nine days, some places only yards apart. Sharpshooters worked continuously, killing many. Union artillery bombarded the Confederates with a battery of 8 Coehorn mortars; the Confederates responded by depressing the trail of a 24-lb howitzer and lobbing shells over the Union positions. Though there were no more large-scale assaults, the casualties for the whole battle were twice as large as that from just the assault on the 10th alone.

The trenches were miserable, but conditions were worse between the lines, where thousands of wounded Union troops suffered horribly in the hot conditions without food, water, or medical help. Grant was reluctant to ask for a formal truce to recover them, because that would be acknowledging he lost the battle. Lee and Grant traded notes from the 12th-14th across the lines without coming to an agreement, when Grant finally requested a two-hour cessation of hostilities, but it was too late for most of the wounded, who were now just bloated corpses. He would be widely criticized for this lapse of judgment in the Northern press.

Command

-US: Ulysses Grant, George Meade

-CS: Robert E. Lee

Army

-US: Army of the Potomac (108,000-117,000)

-CS: Army of Northern Virginia (64,000)

Casualties

-US: 15,193; (2,655 killed; 10,347 wounded; 2,191 captured/missing)

-CS: 4,703; (691 killed; 3,109 wounded; 903 captured/missing)

Notable Casualties

-US: Brig Gen John Martindale*

-CS:

Last edited:

The proto wwi style battle has now locked in. Question is can Lincoln keep the losses suppressed like he did OTL.

Chapter 15: The Campaign Continues (Part 3)

JJohnson

Banned

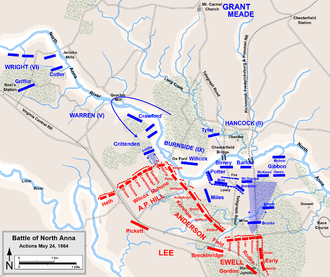

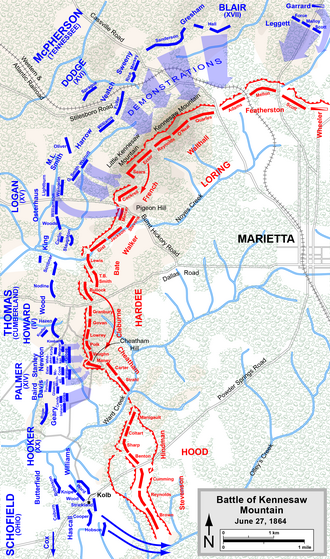

Battle of Rocky Face Ridge (June 10-16)

In Whitfield County, Georgia, the Union army under Maj. Gen. William Sherman faced off against General Joseph E. Johnston.

General Johnston had a strong entrenchment on the Rocky Face Ridge, and eastward across Crow Valley. The Union forces demonstrated against the Confederates with two columns, while he sent a third through Snake Creek Gap to the south to hit the railroad at Resaca.

The first two columns engaged the Confederates at Buzzard Roost (Mill Creek Gap), and at Dug Gap, while the third column, under Maj. Gen. James McPherson passed through Snake Creek Gap, and found the Confederates entrenched there.

McPherson pulled his column back, fearing the strength of the Confederates there. On the 12th, Sherman decided to join McPherson to take Resaca. Sherman's army withdrew from the ridge. Johnston discovered his movement, and retired south towards Resaca.

Command

-US: William Sherman

-CS: Joseph Johnston

Army

-US: Military Division of the Mississippi

-CS: Army of Tennessee

Casualties

-US: 1240

-CS: 455

Siege of Petersburg (June 10-November 9)

Soldiers in the trenches

Grant at this point had engaged in a series of bloody battles of maneuver with Lee, which pushed Lee closer and closer to Richmond. Grant suffered tens of thousands of losses, as did Lee, which earned Grant the nickname "butcher" in northern newspapers. But Grant could afford those losses, and he didn't believe Lee could; Grant didn't believe that slaves would fight for the Confederates in any great number.

Grant decided to change strategies. Instead of maneuvering him into fighting in the open, he decided to attack his main supply base, Petersburg. It supplied Richmond and his army, and was the main supply base and rail depot for the entire region. If he could take it, it would be impossible for Lee to continue defending the capital. Lee thought Grant's main target was Richmond, and only devoted a small number of troops under General P.G.T. Beauregard to defend Petersburg.

About half of Petersburg's population was black and 36% of Petersburg was free black and a large number of Virginia's black population, both free and slave, enlisted to help the defense of the city for various reasons and in various capacities. Once the emancipation bill came through, many of the blacks would earn enough to buy the freedom of relatives and spouses once the war was over.

While the Union's United States Colored Troops would come to serve in the XXV Corps in the Army of the James, being between 9,000 and 16,000 troops, the number of black Confederates defending Petersburg numbered about 12,000, including a diversion of a number of troops originally intended to go join General Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. US Colored Troops would go on to participate in 6 major engagements, and earn 15 of 16 Medals of Honor awarded to black US troops, and the Confederate counterparts earned 18 of 24 Medals of Honor awarded to black Confederates.

Initially, 15,000 Union troops faced off against 14,400 Confederates, including 9,000 black Confederates who were sent in once the Union arrived, building earthworks and trenches. It would peak at about 70,000 Union troops to the 48,000 Confederates.

Layout of the defenses and Union attacks

Initial assault on June 10

While Lee and Grant were sparring with each other, Benjamin Butler believed the defenses of Petersburg to be in a vulnerable state, as its troops came north to reinforce Lee. Being sensitive to his failure at the Bermuda Hundred campaign, Butler was looking for a success to vindicate his generalship. He wrote in his memoirs, "the capture of Petersburg lay close to my heart."

Petersburg was protected by multiple lines of fortifications, the outermost being the Dimmock Line, a line of earthworks and trenches 10 miles long and 55 redoubts, east of the city. The initial defense of 2500 Confederates were stretched thin, commanded by Brig. Gen. Henry Wise, the former Virginia governor. Despite the number of fortifications, at the start of the siege, cavalry could just ride through because of a series of hills and valleys around the outskirts of town, till they reached the inner defenses of the city.

Butler's plan was to cross the Appomattox with three columns, and advance with 4500 men. First and second, columns of infantry, and the third was 1300 cavalrymen under Brig. Gen. August Kautz, which would sweep around Petersburg and strike from the southeast. They moved out on June 8 but made poor progress by encountering numerous Confederate pickets. The assault began at Battery 27. also known as Rives's Salient, manned by 150 militiamen commanded by Maj. Fletcher Archer.

The Union started their assault with the 11th Pennsylvania Cavalry against the Home Guard, consisting initially of teens, elderly men, wounded soldiers, and freed slaves newly enlisted into the armed forces. The Home Guards retreated into the city with heavy losses, but by this time Beauregard brought out reinforcements from Richmond and Petersburg, which were able to repulse the assault, and began the large-scale reinforcement of the line with newly enlisted black Confederates.

Meade's Attempts (June 16-19)

Meade's assaults

By the 16th, Beauregard had 50,000 Union troops facing his 14,000 men. A bout of indecisiveness from Hancock appeared to spare Petersburg for a few days till Meade arrived.

The Union had a series of uncoordinated attacks on the 16th, and continuing on the 17th as more black Confederates poured into the lines to man them and fight them off. During the day, Confederate engineers built new defensive positions and assigned their new troops to them as well. Lee even sent some of his veterans, two divisions under Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw and Charles Field to aid in training and ensuring the men could defend the city well. Unfortunately, the Union got the V Corps of Maj. Gen. Gouverneur Warren brought them up to 67,000.

On the morning of the 18th, Meade went into a rage at his corps commanders due to their failure to take the initiative and break through the Confederate positions and seize the city. He ordered the entire Army of the Potomac to attack the Confederate defenses. The first attack began at dawn, by the II and XVIII Corps on the Union right. The II Corps made no progress, as they met up against a full line of defenses by black Confederates, all dressed in gray, halting their progress as they met heavy Confederate fire for hours*

By noon another attack plan was devised to try to break through the Confederate defenses. However, by this time, parts of Lee's army had reinforced Beauregard's troops, and passing on their wisdom to the new recruits. By the time the Union attack started again, Lee himself took command of the defenses.

Maj. Gen. Orlando Willcox's division of IX Corps led the next attack, but suffered significant losses in the march and open fields crossed by Taylor's Branch. Warren's V Corps got halted by murderous fire from Rives's Salient; Col. Joshua Chamberlain was seriously wounded in this attack while commanding the 1st Brigade, 1st Division, V Corps. At 6:30 PM, Meade ordered his last assault, which also had more horrendous losses. One of the leading regiments, the 1st Maine Heavy Artillery Regiment lost 632 of 900 men in the assault, the heaviest single-battle loss of any regiment during the whole war.

Having gotten almost nothing from four days of assaults, and with Lincoln facing re-election in the coming months in the face of a loud public outcry against the casualty figures, Meade ordered his army to dig in, starting the actual siege. During 4 days of fighting, the Union had 13,188 casualties (2,688 killed; 8.556 wounded; 1,944 missing/captured)

*Originally, Beauregard moved back to the second line; here he has enough troops to man the first line.

Wilson-Kautz Raid (June 22-July 1)

At the same time as the Jerusalem Plank Road infantry action, Brig. Gen. James Wilson was ordered by Meade to conduct a raid to destroy as much track as possible south/southwest of Petersburg. He was assigned Brig. Gen. August Katz's small division to help the effort. The 3300 men and 12 guns departed early to destroy the railroad tracks 7 miles south of Petersburg at the Weldon Railroad at Reams Station. Kautz's men moved west to Ford's station and began destroying track, locomotives, and cars on the South Side Railroad.

The next day, they encountered elements of Rooney Lee's cavalry between Nottoway Court House and Black's and White's (now Blackstone). The Confederates struck the rear of his column, forcing Col. George Chapman's brigade to fend them off. Wilson followed Kautz along the South Side Railroad, destroying about 30 miles of track as they went. On the 24th, while Kautz remained to skirmish near Burkeville, Wilson crossed over to Meherrin Station on the Richmond and Danville to begin to destroy track there.

On the 25th, Wilson and Kautz continued tearing up track, and encountered the Home Guard commanded by Capt. Benjamin Farinholt, with about 1,400 black recruits, a mix of free men and freed slaves newly recruited back in April. They were dug in with earthworks and artillery positions at the bridge. Kautz's men never got closer than 80 yards. Lee's cavalry closed in on the Union troops from the northeast and skirmished with the rear guard of Wilson. Union casualties came to 55 killed, 49 wounded, and 39 missing or captured. Confederates lost 9 killed and 23 wounded. Kautz's men gave up and retreated to the railroad depot at 9 PM. Despite these minor losses, the two Union cavalry generals decided to abandon their mission, leaving the Staunton River bridge intact, having inflicted only minor damage on the railroads.

As Wilson and Kautz turned back to the east after the defeat at Staunon River, Rooney Lee's cavalry pursued and threatened their rear. Meanwhile, Lee ordered Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton's cavalry, which was engaged with Torbert's Union cavalry at Trevilian Station on the 11th to 12th, to join the pursuit and attack Wilson and Kautz.

Before leaving on his raid, Wilson was assured by Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys, Meade's chief of staff, that the Army of the Potomac would be immediately taking control of the nearby railroad as far as Reams Station, so Wilson thought he would be able to return to safety there. Unfortunately for him, the defeat at Jerusalem Plank Road meant that promise would not be kept. Wilson and Kautz were surprised on the 28th when they got to Stony Creek Station, and were faced with Confederate Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton's cavalrymen and infantry blocking their path. They tried to break through but failed. They slipped out of a Confederate trap and rode north to Halifax Road to try to reach Reams Station.

On the 29th, Kautz approached Reams Station, expecting to find friendly infantry, but instead found Mahone's division behind well-constructed earthworks. Kaurtz's attacks were unsuccessful, and Mahone countered against their flanks. Brig. Gen. Lunsford Lomax and Williams Wickham maneuvered around the Union troops and turned their flank. Wilson managed to send a message through to Meade requesting help, but Wright realized it would take too long, so he requested Torbert's cavalry to help. Torbert demurred, complaining of worn out horses and men.

Caught in the trap without promise of immediate aid, the Union raiders tried to burn their wagons and destroy their artillery, but the Confederates were able to stop them before they could do so; the men escaped with casualties of 1,688, but managed to destroy 60 miles of track. Given the lost equipment, Grant reluctantly described the expedition as a "disaster," but Wilson would count it as a strategic success. The captured Union artillery would soon find its way into the defense of Petersburg.

First Battle of Deep Bottom (July 28-30)

Preparing for the forthcoming battle near Petersburg featuring the mine (Battle of the Crater), Grant wanted Lee to dilute his forces by forcing him to attack elsewhere. He sent Hancock's II Corps and two divisions of Torbert's Cavalry Corps across the river to Deep Bottom by pontoon bridge to advance against the Confederate capital. His plan was to pin down Confederates at Chaffin's Bluff, and prevent reinforcements from opposing Torbert's cavalry, which would attack Richmond if possible. If not, Torbert would ride around the city and cut the Virginia Central Railroad, which was supplying the city from the Shenandoah Valley.

Lee found out about Hancock's movement, and ordered the lines to be reinforced at Richmond to 18,500 men. Black recruits were being forced into defenses, rather than in a real fight with Grant.

The II Corps took up positions at New Market Road and captured the high ground on the right, but were counterattacked and driven back. Confederate works on the west bank of Bailey's Creek were formidable, so Hancock chose not to attack and instead performed reconnaissance.

While Hancock was blocked at Bailey's Creek, Lee began bringing up more reinforcements from within Richmond - enlisted freedmen, not reacting as Grant hoped. Ewell was assigned to the Deep Bottom sector.

On the morning of the 28th, Grant reinforced Hancock with a brigade from the XIX Corps. Torbert's men tried to turn the Confederate left, but their movement was disrupted by Confederate attacks. Three brigades attacked Torbert's right flank, but were hit by heavy fire from Union repeating carbines. Mounted Union troops in Torbert's reserve followed and caught about 200 prisoners.

By afternoon, the combat had stopped and the Union stopped attacking the rails. Grant was frustrated and turned instead to the idea of using a mine to blow a hole in the Confederate line.

Battle of the Crater (July 30)

Battle plan (July 30)

Grant was hoping to defeat Lee's army without a lengthy siege, having already experienced the damage it could do to morale with the Siege of Vicksburg. Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants seemed to have a novel proposal to solve his problem. The man from the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry in Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside's IX Corps was a mining engineer when he was a civilian, and proposed digging a long mine shaft under the Confederate lines, and planting explosive charges directly underneath a fort (they would decide on Elliott's Salient) in the middle of the Confederate First Corps line. If successful, Union troops could drive through the resulting gap in the line. Diggin began late in June, creating a mine with a T shape, with a 511-foot approach shaft, and at the end a perpendicular line of 75-feet in both directions. They filled it with 8,000lb of gunpowder, buried 20 feet under the Confederate works.

Burnside had trained a division of US Colored Troops under Brig. Gen. Edward Ferrero to lead the assault. Two regiments would leave the attack column, and extend the breach, while the remaining regiments were to rush through and seize the Jerusalem Plank Road. Burnside's two other divisions of white troops would then move in, supporting Ferrero's flanks and the race to take Petersburg.

The day before the attack, Meade, who lacked confidence in the operation, ordered Burnside not to use black troops to lead the assault. When volunteers didn't come forward, he selected a replacement division by drawing lots. Brig. Gen. Ledlie's 1st division was chosen, but he failed to brief the men on what was expected of them, and was reported during the battle to be drunk, well behind the lines, providing them no leadership.

At 4:44 AM on the 30th, the charges exploded in a massive shower of earth, men, and guns. A crater 170' long, 60-80' wide, and 30' deep was created, and is still visible today.

Sketch of the explosion

The blast destroyed Confederate fortifications in the vicinity, and instantly killed between 250 and 350 Confederates. Ledlie's untrained white division wasn't prepared for the explosion, and waited ten minutes before leaving their own entrenchments. Once they wandered to the crater, instead of moving around it as the black troops had been trained to do, they moved down into the crater itself. Since this wasn't the planned movement, there were no ladders provided for the men to use to exit the crater.

The Confederates, under Maj. Gen. William Mahone, gathered as many troops as they could for the counterattack, over 70% of which were black Confederates. They formed up within an hour's time, and began firing rifles and artillery down into the crater, in what Mahone would later call a "turkey shoot." The plan failed, but instead of cutting his losses, Burnside sent in Ferrero's men. Now facing flanking fire, they also went down into the crater, and for the next few hours, Mahone's soldiers, along with those of Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson and artillery, slaughtered the men of the IX Corps as they tried escaping the crater they had created.

Some Union troops eventually advanced and flanked to the right beyond the Crater to the earthworks, and assaulted the Confederates' lines, driving them back for a few hours in hand-to-hand combat. Mahone's Confederates conducted a sweep out of a sunken gully area about 200 yards right of the Union troops' advance, reclaiming the earthworks and driving the Union force back towards the east.

Grant's Personal Memoirs would mention this, "It was the saddest affair I have witnessed in the war." Union casualties were 3996 ( 651 killed, 1,926 wounded, 1,419 missing/captured), Confederate casualties about 1410. Many of the losses were suffered by Ferrero's division of the USCT. Burnside was relieved of command after this.

Second Deep Bottom (August 14-20)

Order of battle