OK. Can you give me a few examples of conciliatory diplomacy after wars in the 19th Century?

- The Treaty of Paris. Although France lost the Rhineland and territories annexed in Italy, Germany and Spain, it conserved its historical borders of 1792, no military restrictions were imposed on her, AFAIK no reparations either. The objective was to restore the European balance of powers, not to indefinitely punish France for the Revolution and Napoléon. France was quickly reintregrated into the European Order as it had its delegates on the Congress of Vienna and concluded an alliance with Britain and Austria against Prussian and Russian interests in Saxony. It was only after France "relapsed" in 1815 (I actually sympathize with those Frenchmen who welcomed back Napoléon in 1815, but that's not the point) that France lost parts of its core territory, that a military occupation and substantial reparations were forced upon her.

- The Peace of Prague. Austria lost its position in the German Federation and was thus excluded from German politics, but reparations were moderate, and neither Austria nor Saxony lost any territory (Bismarck successfully stopped his monarch from annexing Austrian territories).

- The Peace of Frankfurt. Although the reparations were indeed a heavy burden imposed on France, and even though the German popular opinion had forced Bismarck into annexing Elsass-Lothringen, the treaty conserved France as a great power on the European continent. It kept its colonies and quickly found the means to repay the Germans in short time, which did quite a bit to scare off Bismarck who went on to plan a war in 1875 in the "Krieg in Sicht"-crises – only to shrink back because both Britain and Russia made it clear that the European balance of power could only suffer from new German gains in the west.

Of course, I don't have to mention that Germany didn't impose any restrictions on French army size in 1871 (which Napoléon did with regard to Prussia in 1807).

As far as I know, all treaties between European countries respected the principle of the Pentarchy and of the balance of power. That's something the Treaty of Versailles did not. It replaced these old rules by new principles of diplomacy, some naive, some very good, but even then both the treaty and those enforcing it didn't stay true to those Ideals.

After the horrors of WW1, it was agreed between the Entente members that vengeful peace would be down right criminal. And a criminal peace was not seen as offering much in terms of security or prosperity.

Yes, but a fair peace, which is durable and beneficial to everyone, can only be a process of a sensible negotiation process. For that, inviting the other party to the negotiation table is more less indispensable. It also helps if you don't destroy the other party's negotiation position by forcing it to an armistice that is a capitulation all but in name. The armistice of 1918 was intended to break Germany's ability to pursue the war.

It's, of cause, understandable why the Entente would want that, but it completely undermined the German negotiating position. Temporarily keeping some of the occupied territories, or at least Elsass-Lothringen, and being able to continue the war (at least for some time) would have allowed Germany to negotiate harder (and to be accepted at the negotiating table in the first place). That would have been closer to an armistice, i. e. to a general ceasefire, than November 1918 was.

Instead, the democratic government of the young German Republic was forced to agree to a treaty that was rightly called a "Diktat" from the first day of its publication. It had no other choice. The army and navy had already lost most of their equipment, the border territories had been abandoned, the armed forces were in the process of demobilization. Turkey had least had the chance to fight for a better settlement.

In theory it is all fine. Of course, in practice everyone acted like they were the chosen ones who deserved special treatment. That their SP&P was a little or a lot more important of that of others. Especially when those others weren't fellow European Christians. Every single participant in the post WW1 peace process fell short in some way. Should we judge them only by their faults though? Or is it worth also judging them by what they aspired to as well?

I think that, fundamentally, we're of the same opinion. Every power had its own objectives and its own need for security and for a territory supporting its economy. The (early) war goals reflect exactly that. Germany wanted to assert European dominance, while Austria-Hungary fought for its survival. Russia had ambitions in Poland, on the Balkans and in the Caucasus, and France wished to regain Elsass-Lothringen pretty much from day one. Britain wanted to preserve the European balance of powers, which had been her aim for centuries.

When the US entered the war, under the principles proposed by President Wilson, it had to deal with those war aims. American, British and Italian goals were easy to bring into harmony, but France, which had, as you write, to bear most of the destructions and feared a fourth German invasion (after all, 1815, 1871 and 1914 had been devastating enough).

In the end, peace was shaped by all those interests, which (partially) interfered with Wilsonian idealism and the high hopes everybody had of the coming peace. British preoccupation with continental balance proved to be a hindrance to ambitions French plans of territorial expansion, while American influence did actually little to restrain France.

Germany ended up separated from substantial territories with a German ethnic majority, and the young German democracy was burdened with reparations that it could not pay in practice. People like Keynes recognized that already as the treaty was signed. And this brings us to the question of enforcement...

It was perfectly enforceable. But enforcing it would cost money and require long-term cooperation. According to the treaty as signed all Entente members were supposed to station troops in the Rhineland DMZ until reparations were fully paid. Just as Germany had occupied a big chunk of France after 1871 until France paid all the blood money demanded after that war. But the British and Americans didn't like that since it violated old traditions, so they bailed on those clauses within a few years. France, Italy and Belgium could have enforced it on their own even so, but at heavy cost to their own economies and to their foreign relations with the US and UK.

Yes, if the UK, the US, France and Belgium had cooperated to enforce the reparations and the payment plan in their first version, they would likely have succeeded by use of sheer military force.

However, Britain and America were of the opinion that at least the individual installments, if not the entirety of the reparations, had to be cut if the German economy was ever to recover from the war. A ruined Germany would have been catastrophic for the European balance of powers and an invitation to communist agitation in Central Europe. I don't know if that, if enforcing the Versailles Treaty really would have been such a good idea.

Not wanted. Needed. At least, if the goal was a sovereign Poland.

Other perfectly sovereign nations like Czechoslovakia did not need such an artificial port.

German speaking people had lived in Poland as Polish subjects for centuries before the partitions. Indeed, German-speaking Poles were often particularly patriotic, since the Polish crown was seen as the best guarantor of the rights of the German cities. So in the bigger picture, Germans could clearly live in Poland.

Germans had lived in Eastern European countries for centuries, that's right, but the German population in question lived in territories adjacent to Germany proper and formed the majority in the regions they lived in. Moreover, nationalism had come by since the first waves of German immigration to Eastern Europe, and the Germans dwelling the annexed territories did not actually want to live under the Polish government – and the German government had no intention to let them go.

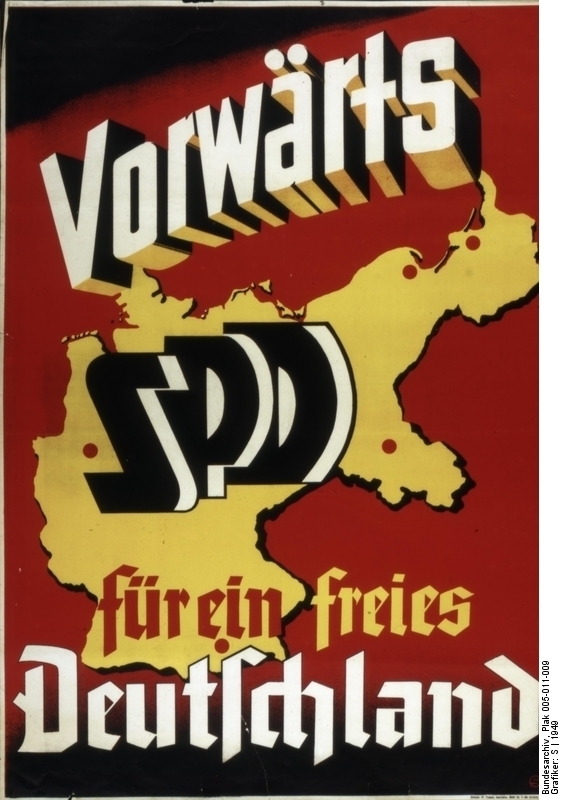

Flash forward 30 years, and you'll see that even socialist parties like the SPD still had no will to let East Germany go – and that was after the horrors of WWII and the complete defeat in 1945:

So, to wrap it up, I don't doubt that the Entente (at least some of its negotiators) had good intentions, whether it was classical British diplomacy or the new Wilsonian idealism, but the very real interests of the victors ended up compromising the objectives of those that wanted a fair and lasting peace. Especially France wasn't interested in an equal coexistence with an equal German partner. They feared Germany way too much to ever allow it to regain its full sovereignty and economic prosperity. The Versailles Treaty, to be durable, needed to be revised, and the French governments were more or less forced to agree to these revisions – mind you, I'm saying that as a (half-) French person.

So yes, I consider the results of the 1919 Entente negations imposed on the former Central Powers as flawed.

*sorry that looks like i'm saying the 2nd was way out of proportion to the first! I'm not I'm just pointing out reparations was a thing. what with inflation in the intervening years and difference in scales of the the two conflicts I'm not sure how unequal they are! (if pushed I'd say 1871 looks steep, but that could be because 1815 was actually light!)

Oh, there's no doubt that the treaties imposed on France in 1815 and 1871 were harsh! In 1815, France had let Napoléon back in and was punished accordingly by the European monarchies, while Bismarck indeed intended the war reparations to prevent France from waging war against Germany for quite some time.

But those reparations were, in contrast to those based on the Treaty of Versailles, not impossible to pay. Indeed, France managed to reimburse Germany pretty quickly, much to the anger of Bismarck and his government, which feared that France might soon take her revenge.

It also involved the Prussian army staying in France until it was paid, and they happily took territory.

They took Elsass-Lothringen, but only because Bismarck was under internal pressure because the public opinion wanted to "take back" these ethnically and culturally German territories (which, as far as we know, politically identified as French).

Again, while the reparations were heavy and the loss of an integral part of the French territory was demoralizing, the Treaty of Frankfurt was nothing compared to the Treaty of Versailles.

Land was always lost in the C19th treaties. the difference is in 1919 it was more fashionable to call it "ethnic self determination" not "we're taking this because you lost". (although TBF I think even in the C19th there was some allusions to ethnic self determination)

The annexation of Elsass-Lothringen being one of the first instances. Parts of the German public opinion agitated for annexation precisely because the territory was considered German in certain ways.

Nobody, however, took the time to ask the Alsatians and Lorrainer about their preferences, so that's another parallel to 1919 and "the right to self-determination".

On top of that WW1 had been proportionally more devastating to the winners having been fought on French soil in the west than pretty much anything in the C19th except maybe the Napoleonic wars for some. There is going to be recompense taken and that means land and resources. Basically to be glib if you want to keep your territory don't lose a war, but really don't lose a war that cripples entire economies, scars entire nations and kills millions in a 4 year meat grinder the likes of which even proportionally hadn't been seen since the wars of religion. i.e fighting wars is a gamble if you lose you will have to give stuff up

Exactly. WWI was, in its length and intensity, unlike all wars of the 19th century, and accordingly was ended by a treaty much different from the more moderate, conciliatory settlements of the preceeding centuries. Which is my entire point.

(i'm not going to get into the whole "who started it" debate suffice to to say it there was little doubt abot it in the minds of the winners in 1919)

I feel that this debate is pretty much settled among (German) historians (it was the German government), but of course it wasn't really for diplomats to decide the question. "It's all your fault" it's not a very good principle to have a fresh start and do constructive, peaceful work.