King George V

Part Three, Chapter Twenty: Holiday Plans

At the Palais Bourbon in the 7th Arrondissement of Paris on the Rive Gauche of the Seine, Lord Betchworth sat in the splendour of an anteroom waiting for his French counterpart, François Guizot, to arrive. A bottle of very expensive of Bordeaux was provided for Betchworth to sip as he awaited the Foreign Minister who finally arrived three hours later than scheduled with his apologies that he had been delayed whilst touring the site of the new Foreign Ministry building on the Quai d’Orsay. In fact, Guizot had been taking an extremely long luncheon at the Austrian Embassy on the Rue Fabert leaving Lord Betchworth to wait his turn until the French Foreign Minister had concluded his talks with the Ambassador Extraordinary of the Austria to Paris, Count Anton von Apponyi. Unbeknown to Betchworth, Guizot had already met with the Prussian Foreign Minister Baron von Bülow too. This had led some historians to conclude that Guizot was very much hedging his bets as he approached the difficult issue of what consequences there should be for Russia when they violated the terms of the Straits Pact. If he was, he had good reason. In the 1830s, two distinct blocs in Europe had developed; the liberal bloc in the West formed of France and the United Kingdom and the reactionary bloc in the East formed of Prussia, Austria and Russia. This latter bloc had come together as the Holy Alliance in 1815 and though fraying at the edges somewhat as Austria feared Russia’s ambitions in the Balkans, the basic principles of the agreement still held firm. The alliance wished to restrain liberalism and secularism in Europe and to uphold absolutist, Christian rule. This meant in practise that Austria, Prussia and Russia would always find themselves wary of French and British foreign policy that was guided by far more liberal principles than the conservative views which directed foreign policy in Vienna, Berlin and St Petersburg.

When the Prussians and Austrians signed the Straits Pact in London in 1841, both parties expressed doubts to the other that it would hold for very long. Austria in particular believed that the Russians would violate their quota agreed in Vienna “within months” and that Prince Gorchakov had only paid lip service to the agreement because the alternative was to lose access to the Straits entirely. The Pact allowed Gorchakov to return to Russia as a hero and indeed, the Tsar was delighted with his achievements in securing maintained access to the Straits. But this did not mean that the Tsar agreed with the idea of a quota system or that he intended to honour it. Thus, the quota had been consistently ignored, Tsar Nicholas telling those who urged caution to remember that Austria and Prussia would not allow the liberal democracies of Britain and France to sanction Russia too harshly. This was about to be put to the test in Paris in 1844 as Betchworth and Guizot met to determine the best possible approach that all nations could agree to and enforce as a united group. Guizot had already gauged the Austrian and Prussian view and both von Apponyi and von Bülow were in full agreement that all signatories should be recalled to Vienna and the quota system used to deter Russia from her current path. Bülow proposed that new quotas should be set which took into account the number of ships the Russians had already sent through the Straits, for example, if Russia was allowed 50 ships then this would be reduced to reflect the number she had exceeded her quota by giving her a new limit of 30 ships instead. The Austrians felt this a proportionate and fair response too. From their standpoint, this not only sent a message to Russia that they must honour their international agreements but it limited the number of Russian ships passing through the Dardanelles into the bargain.

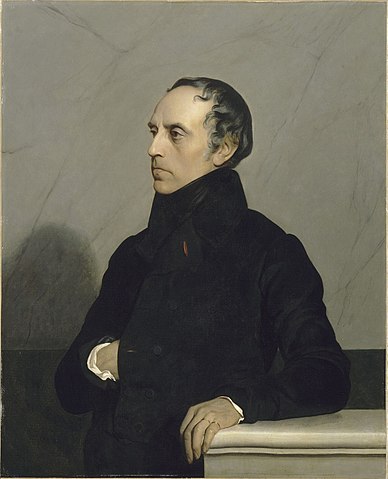

François Guizot

“It is the most likely outcome”, Guizot said mournfully as he poured himself a glass of wine, “But it is not an outcome I believe we should accept. I have presented the facts to His Majesty as they are and it is his belief that this will send quite a different message to the Tsar – that he has still gained access to the Straits he would not have otherwise have had, even when he breaks his promises”.

Betchworth sighed.

“I quite agree Guizot”, he said, “The agreement was always to enforce economic sanctions, all nations signed to that effect in London”.

“Then it shall be war”, Guizot replied, shrugging his shoulders.

He had good reason to presume so. In the 1840s, “economic sanctions” meant one thing and one thing only – a blockade. This strategy was first tested in 1827 when Britain, France and Russia deployed a fleet off the Greek coast to interrupt supply lines to the Turks and the Egyptians. At first, the blockade worked but within days, the fleet (which was strictly forbidden from engaging militarily) opened fire on a Turkish ship and the result was a full-scale naval battle at Navarino which resulted in the loss of the entire Turkish and Egyptian fleet and 7,000 men. Nobody wanted to risk a similar outcome in the Dardanelles which would no doubt trigger an all-out war between the Great Powers. [1]

“If we do not follow the agreement to the letter, how can we possibly uphold it?”, Lord Betchworth said impatiently, “No Guizot, I am sorry, but what they are suggesting makes the Pact totally redundant. What is to stop the Tsar sending another 50 ships through the Straits on the pretext that he was simply pre-empting a new quota next year? I have put together my own proposal, one I hope you will give serious consideration to…”

Betchworth laid some papers before Guizot who nodded kindly and began to skim read them. What Lord Betchworth was proposing was a declaration signed by France, Britain, Austria and Prussia which would be sent to the Ottoman Sultan demanding that all Russian ships passing through the Straits should be halted at Gallipoli, their holds surveyed and their cargo valued. A customs charge of 15% of the total value of the cargo must then be applied and paid before the ship was allowed to proceed on to Constantinople, provided of course that it was not in violation of the quota in the first place. Guizot nodded approvingly. It offered practical and direct sanctions which may not be enough to deter the Russians from breaking the terms of the Straits Pact in the future but might open the door to increased charges if they did so, all within the nature of the agreed penalties but without risking a military clash between the Great Powers. Guizot gave the so-called Betchworth Declaration his full support and promised to put it before the Ambassador of Austria later that evening and the Prussian Foreign Minister the next morning but he was not hopeful that either party would bend to accept it. Betchworth sent word back to England that he had presented his proposals and was “moderately hopeful” that they would be accepted.

Though the King had asked to be kept well informed on the outcome of the Paris talks, he did not see Betchworth’s briefing when it arrived in London as he was still in Scotland, or more specifically, he was preoccupied with house hunting in the Highlands. It is said that the Balmoral estate near the village of Crathie in Aberdeenshire was once home to a hunting lodge favoured by King Robert II of Scotland in the 14th century and caused much animosity when it was gifted by Robert’s successor to the 1st Earl of Huntly. The Gordons wasted no time in tearing down the hunting lodge and replacing it with a family home and whilst they continued to entertain the great and good on the estate, naturally they felt no need to open their doors (and their 50,000 of prime hunting ground) to those who had always been guaranteed an invitation in days of old but didn’t quite fit with the new Balmoral set.

This remained the case for nearly 300 years until 1662 when Balmoral passed from the Gordons to the Farquharson family. There were two distinct branches of the Farquharsons – those who had Jacobite sympathies and those who did not. The Jacobite Farquharsons from Inverey held the deeds to the Balmoral estate from which they travelled to Falkirk Muir to fight Bonnie Prince Charlie. Though a Jacobite victory, the advantage was wasted and shortly after the Young Pretender was defeated at Culloden, his supporters found themselves stripped of their estates with Balmoral transferred from one lot of Farquharsons (now disgraced) to another branch of the family who hailed from Auchendryne. But these Farquharsons hadn’t a penny to bless themselves with and they quickly sold Balmoral on to the Earls Fife in 1798. The Fifes were drawn to Balmoral for exactly the same reason as King Robert II had been but when they arrived, they found the house beyond repair and despite the luxury of 50,000 acres stretching from the Cairngorms to Lochnagar, they sold the estate to Lord Aberdeen – a descendant of the Gordon family who had once called Balmoral home for three centuries.

Old Balmoral Castle.

In 1830, a new house was built at Balmoral to replace the crumbling mansion the Fifes had been unable to restore and thereafter the estate was leased to the unfortunate Sir Robert Gordon who lived at Balmoral for just 14 years before ignominiously meeting his maker as the result of a poorly boned fish supper [2]. Sir Robert had made extensive changes to the house by the time King George V visited in 1844, yet as caught up in Highland romance as he was even His Majesty could not ignore the obvious – Balmoral Castle was (by the standards of such buildings) a poky, uncomfortable little house with no discernible charm, let alone indoor plumbing. The King remained open minded as John Burnett gave him a tour of the ground floor which was comprised of an entrance hall leading from the carriage porch that gave access to a library, drawing room, billiard room and dining room. Across the gallery was a grand staircase leading up to the first floor which boasted three large bedrooms each with dressing room and anteroom, though there was a visitor’s suite on the ground floor which offered a double bedroom with private drawing room and study thrown in for good measure. Though this may sound quite grand however, the state of the rooms themselves left much to be desired. Peeling wallpaper, flaking paint and smashed windows did little to give the place a cheery atmosphere. The King felt a little dejected and was almost relieved when Downie arrived with ponies for the next leg of the tour – the estate itself.

From the Dee river valley to open mountains, the Balmoral estate is nestled partly in the Cairngorms and partly in Lochnagar with seven hills over 3,000ft providing an abundance of wildlife from the grouse on the moors to the red deer in the Munros. As the King and his party made their way to Loch Muick in the southeast, the King spotted a boat house and a hunting lodge and Downie confirmed that there was ample opportunity not only for fishing and stalking but for farming and cattle-raising too. Cutting their way through the estate, the King was so taken with the landscape that he ordered Burnett, Downie and Phipps just to stand for a time and take it all in – an appreciation that lasted for nearly an hour and a half in a chill wind. Then they moved on to the edge of the estate which had been marked out with pegs and rope to give the King an idea of where his potential investment would end and where the neighbouring estate began.

“What is that little house down there?”, the King called into the wind.

“That is Birkhall, Your Majesty”, Burnett explained, “But that’s stood empty for many a year now”

“Who owns it?”, the King asked.

“Lord Aberdeen”, Downie replied sourly, “But he prefers Abergeldie”.

“Does he indeed?”, George smiled [3].

Back at Crathes Castle, Princess Mary was dozing by the fireside but upon hearing the approach of heavy footsteps, sat bolt upright and pretended she had been wide awake at her embroidery. Through bleary eyes, she caught sight of her nephew and Mr Burnett engaged in hushed conversation.

“How was it dear?”, Mary asked, stifling a yawn, “You look half-frozen! I shall ring for tea; some hot buttered toast will cure all ills”

The King walked over to his aunt and gently kissed her on the cheek.

“Fascinating place”, George smiled, “But the house is very small and quite run down. I shall ask Lord Aberdeen to see me when we return to London…”

The King suddenly looked downcast.

“As I’m afraid we must”, he said somewhat mournfully, “I will confess I have greatly enjoyed my time here. I shall be sad to go”

“Well then”, Mary beamed, “All the more reason to speak with Lord Aberdeen”

The possibility of acquiring a new holiday home in the Highlands enthused the King and made his leaving bearable. On his journey home from Scotland, he spent hours with his head buried in a notebook making doodles of possible renovations to the house he had toured and writing long lists of the most obvious ways to make Balmoral more comfortable. Yet his holiday was over and though his Scottish tour had been a success, he did not relish his first post-vacation audience with the Prime Minister whom he feared may offer bad news. When the King left London, the Leader of the House honoured Sir James’ promise and introduced the Succession to the Crown Act and the Royal House Act to the Commons. The division was to take place on the same day the King arrived back in London and so George could have no idea if the legislation had passed the first hurdle as his carriage rocked him back and forth all the way from St Katharine Dock to Buckingham Palace. But even if the bills had passed, and the Prime Minister seemed certain they would, the King would still be returning to a delicate situation borne of the fallout of his proposed reforms to the monarchy. The Cambridges had by now returned to Hanover, awaiting to hear who would succeed them at Herrenhausen, but they left behind a bad atmosphere that had followed a tense family quarrel and this played on the King’s mind as he prepared to receive the Prime Minister once again.

Sir James quickly reassured the King that both the Succession to the Crown Act and the Royal House Act had passed as expected and now awaited the approval of the House of Lords. He also presented the King with a selection of clippings too, all glowing reports from George’s tour, as well as a silver charger as a gift from the Cabinet as a token of their congratulation for his efforts. The King was greatly cheered by this kind gesture and spent the majority of the audience waxing lyrical about the benefits of the Highland air. He did not however, mention that he had in mind to acquire a property there, feeling that it was far better to see if Lord Aberdeen was open to selling the lease to Balmoral before he introduced the topic at an official level. Instead, the King intended to turn the conversation to the appointment of a new Viceroy in Hanover.

“Of course, I shall have to make the decision quite soon”, George said, pouring Sir James a glass of brandy, “My Uncle wishes to return home at the earliest opportunity and I should like to have the matter settled before my trip to Hanover in August”

“On that point Your Majesty…”, Sir James took a sharp intake of breath and leaned forward a little, “It did occur to me that, with the success of this tour, we might look closer for an end of summer tour than Hanover”

“I don’t follow…”

“Your Majesty’s visit to Scotland won all hearts and revived the sense of loyalty felt for the Crown, and indeed the Union it represents, in all the places where you were seen by the people”, Graham began, “This success was much appreciated by Your Majesty’s government as our small token of thanks indicates, but the Cabinet did wonder in your absence if we might not extend that same approach to the country as a whole. You see Sir, back in 1822 when Your Majesty’s late father conducted a similarly effective tour of Scotland, it was to be followed by a royal progress of England. But alas, only one half of the proposed progress was made. You will be aware Sir that we do we face significant difficulties in the industrial towns, especially in the north, there are elements who wish to increase radical sentiments. These sentiments were equally to be found in Scotland until Your Majesty visited and yet now they are calmed by virtue of the Sovereign's presence. Therefore, I should like to ask if you would consider making a similar tour of England throughout the summer”

The King raised an eyebrow.

“Before I leave for Hanover?”

Graham shifted in his seat nervously.

“Unfortunately Sir, I fear we may have to prioritise a little. Hanover has had the great fortune of hosting Your Majesty on consecutive summers but the people of Lincoln or Manchester for example, have yet to greet their King as they would wish. I would advise too that the situation in the north may decline further given the economic situation we face, I should like to feel that same reassurance I have taken from Your Majesty’s tour of Scotland which no doubt would follow a similar tour of England”

The King shook his head.

“No Sir James”, he said brusquely, sinking into a chair, “It’s just not possible I’m afraid. I have asked the Chancellery at St James’ and the Deputy Earl Marshal to draw up a suitable investiture ceremony for the new Viceroy in Hanover, I must be there when that happens”

There was a brief moment of silence. Sir James looked down at his papers.

“Well?”

“Your Majesty…”, the Prime Minister sighed, “If it is your wish that you should go to Hanover for the investiture of the new Viceroy then I shall of course accept your decision without hesitation. But I feel I am duty bound to inform you that such frequent visits have given rise to criticism”

“What criticism?”, the King scoffed, “I can’t believe that”

“Nonetheless Sir, it exists”, Graham said bluntly, “I cannot forbid you from going to Hanover, I should not wish to do so either. But I must stress to you the difficulties this problem has caused in the past and as I have already explained, there is a greater need for Your Majesty’s presence here this year than there may be elsewhere. If you would consider what I have said and let me know within the week what your decision is, I should be most grateful”

Slightly stunned, George rose to his feet and shook Graham’s hand. He stood in silence for a few minutes until Charlie Phipps walked in to announce the arrival of Lord Aberdeen.

“Is everything alright Sir?”, Phipps asked, noticing that the King wasn’t really paying much attention to him.

“What? Oh fine Charlie, perfectly fine”, he lied, “Send Lord Aberdeen in would you?”

The dispute over where King George V might spend the latter half of his summer was about to take on a new dimension over the next few days. The King called Count von Ompteda to Buckingham Palace to gauge his view on the criticism the Prime Minister had spoken of. But Ompteda misunderstood. Instead of confirming (or denying) that some in smart social circles had taken issue with the King going abroad too often, Ompteda believed that the King had heard the latest from Hanover where several members of the Landtag had banded together to produce a bill demanding reforms to the appointment of a new Viceroy. A group of politicians in Hanover were proposing a special committee to be formed which would produce a list of suitable candidates which could then be proposed to the King for him to choose from. There was a feeling in Hanover that the Duke of Cambridge’s tenure had only been allowed to go on for so long because of a sense of affection the majority there felt for him personally. But Hanover was a very different place in 1844 than it had been in 1811 when the Duke first took up the Viceroyalty. Hanover had its own parliament, a liberal, modern constitution and an active political class which wanted more authority over decisions made affecting their homeland – not less. Rather clumsily, Ompteda then mentioned that some had also voiced opposition to the Royal House Act in Hanover because it gave the impression that “any prince who steps beyond the bounds of respectability in England may adopt a Hanoverian title which suggests that the same standards do not apply there”. The King was outraged at the very suggestion and Ompteda awkwardly left the Palace later that evening feeling he had inadvertently kicked a hornet’s nest. George was now absolutely determined to push on with his plans regardless. He would go to Hanover come hell or high water and face down any suggestion that he did not value Hanover or worse, that he was some kind of absentee tyrant landlord imposing unpopular authority figures on the population. He was also determined to get a new Viceroy in place who would accompany him on his travels.

To this end, the King summoned his cousin the Earl of Armagh to Buckingham Palace. Though His Majesty was loathe to see Prince George leave England, and whilst he had hoped that the Earl and Countess of Armagh would begin to carry out a programme of public duties, Ompteda’s words forced the King once again to put duty before family ties. He formally offered the position of Viceroy to his cousin with a view to taking up the role in August 1844. But there was a small snag. When the King had invited the Armaghs to join him at Crathes, they had been unable to do so because the Countess was unwell. It did not take long before it was confirmed that Princess Auguste was expecting a baby. The intensity of the King’s day suddenly lifted into joyous celebration and an impromptu supper party was held at Buckingham Palace so that His Majesty could congratulate Auguste personally.

Princess Mary was equally delighted, though she joked that the Armaghs should be forbidden from calling their child ‘George’ to avoid further confusion within the ranks of the British Royal Family. After the meal, the King and the Earl of Armagh were reunited in the King’s Study and once again turned their attention to Hanover. Prince George had discussed the matter with his wife and both were in absolute agreement that they were prepared to serve the Crown in any way asked of them but because of the Countess’ pregnancy, the couple felt they should leave sooner rather than later so that they had plenty of time to settle in their new home before Auguste's confinement began. The King saw this as eminently practical, yet he did not wish to bring forward the Earl’s investiture as Viceroy – possibly because he knew if he did, he would lose the justification for ignoring the Prime Minister’s advice to remain in England that summer instead of going to Hanover. However, another justification for his trip, albeit a very personal one, was about to emerge.

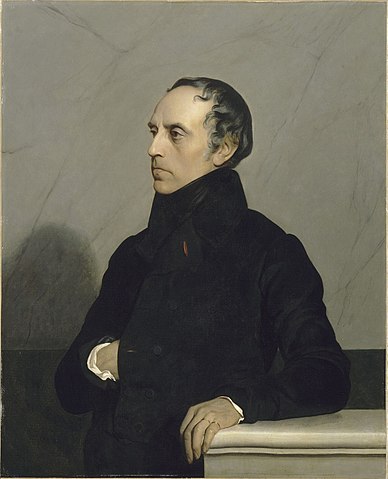

Frederica, Duchess of Anhalt-Dessau.

When the invitation for Princess Agnes to travel to England to stay with Frau Wiedl had been extended, the Duchess of Anhalt-Dessau gave no indication that she opposed such a trip and seemed to give her blessing (though as ever in her usual stony-faced way). Yet now she protested that it was quite unthinkable and that even with a chaperone, Agnes was far too young and far too immature to be allowed to throw herself into the social whirl of England mid-season. The Duchess forbad Agnes to go unless she herself was invited to accompany her daughter, something Frau Wiedl had wished to avoid. This wasn’t only based in Rosalinde’s dislike of the Duchess (which was universal in such circles) but because she worried that the presence of Princess Agnes’ mother would make it harder for the King to spend quality time alone with the girl he clearly had developed very strong feelings for. Many years later, the Duke of Clarence (1850 – 1934) reflected on Frau Wiedl’s role as matchmaker which has proven quite the hurdle for those historians who insist that George V’s relationship with her was far from platonic. In a letter to his biographer, the elderly Duke wrote “Aunt Rosa was a curious woman to me for she was of course a great beauty in her time and I often wonder why my father never showed the slightest interest in her romantically. But the fact remains he did not. I once asked why she had been so keen to see my Papa remarry. She said it was because Papa was so very sad at the loss of his first wife and that my darling Mama made him so very happy. I appreciate we now live in a very cynical world and that her words may seem trite but I assure you this is what was told to me and I do believe that to have been her only motivation”.

But one does not have to go too far to find a different point on view on the subject. In a letter to her niece, Princess Beatrice, Princess Victoria writes; “Eddo is quite wrong on the subject. Aunt Rosa had nothing whatsoever to do with it! Papa was encouraged to marry again by poor Great Aunt Mary who was always so silly about these things. I do not believe Aunt Rosa pushed him in any direction on that subject – it was not her place to do so when all is said and done – and I know that is quite true that the introduction was made by Cousin Alex Prussia, because he was related in some fashion to the Anhalts. Eddo knows this to be the case for I have discussed it with him long before now so I do not understand why he should be in such a muddle about it all now”. For all her objections however, it does appear that the Duke of Clarence was correct in his assessment. Frau Wiedl wanted the King to find happiness once more and believed he had found it with Princess Agnes. Offering to host Agnes at Radley put distance between the King and Agnes on an official footing in that the court at Windsor would not have been set abuzz with gossip at the Princess’ speedy return so soon after her departure at Christmas which perhaps gives the clearest indication that Wiedl was trying to create an atmosphere in which the King felt comfortable to explore all avenues with his new love interest – including marriage.

This was of course a moot point however for as long as the Duchess of Anhalt-Dessau refused to let her daughter go to Radley for the summer. The Anhalts were by no means naïve and naturally they had discussed the fact that the British monarch now seemed to be taking a very keen interest in their eldest daughter. Initially, the Duchess waived the development as a passing fancy. Though she did not consider her daughter to be very attractive, she recognised that she had many other favourable qualities which she could understand a young suitor might find appealing. That said, the Duchess was not particularly welcoming to the idea of King George V as a potential son-in-law. She harboured a grudge (a rather silly one) against the British Royal Family for the “outrageous neglect” they had poured on her late mother, the Duchess of Cumberland. However, there was far more to the situation than that. In reality, the late Duchess of Cumberland had shown very little interest in her children from her first marriage following the death of their father Prince Louis Charles from diphtheria in 1796. Indeed, within two years the Duchess had fallen pregnant outside of marriage following a disastrous liaison with Prince Frederick William of Solms-Braunfels. A drunkard and a womanizer, the Prince married Frederica to make a respectable woman of her but as their family grew, his behaviour worsened. So much so that by 1805, he lost his income and Frederica’s brother advised her to petition for divorce. She initially refused but by 1813, she had met the Duke of Cumberland and changed her mind. When the separation took longer than expected however, Prince Frederick William died leaving Frederica to remarry. As she had done with the children of her first marriage, the children of her second were scattered to the wind, boarding with cousins, uncles or aunts, leaving Frederica to pursue other interests – namely in trying to find a way in which she might be accepted by her third husband’s family. [4]

In short, the late Duchess of Cumberland had only ever been treated poorly by the British Royal Family because she had a reputation as a scandalous woman and because she then chose to marry a notorious man in Prince Ernest Augustus, he already being deeply unpopular in England by the time of their wedding. Of course, the Duchess of Anhalt-Dessau did not see it that way. She remembered only too well how her godmother, aunt and namesake had been treated by the then Duke of York, Frederica of Prussia being declared mad so that the Duke could have his marriage annulled before his accession, later marrying Louise of Hesse-Kassel, the mother of King George V.

Whilst the rest of the Prussian Royal Family held no grudges about this complicated tangle, the Duchess of Anhalt-Dessau most certainly did and though she had accepted the King’s hospitality, she was not at all enthused at the prospect that her daughter may accept his proposal of marriage if the time came. The Duke of Anhalt on the other hand, was more supportive. Secretly he detested the way his wife treated their children with such a dominant and unbending approach and he had always tried to act as peacemaker within his family, finding quiet compromises to placate his wife whilst also giving his children what they wanted. Now he intended to do the same again for whilst he had some reservations about his daughter marrying into the British Royal Family, he genuinely believed that any match between George V and Princess Agnes would be one borne of love and affection – something he wished all his children, perhaps because he had not experienced it in his own marriage.

Yet his wife remained determined. She would not allow her daughter to go to England for the summer and instead, proposed that the Anhalts began to invite eligible princes to Dessau instead in the hope that Agnes might prefer one of them to King George V, thus ending the “absurd Windsor romance” which the Duchess thought “utterly hopeless and in no way advantageous to us”. Princess Agnes was absolutely crushed at the thought that she would not be allowed to go to Radley and spent days weeping as her father seemed once again to bow to his wife’s commands. Indeed, he made it all the worse for Agnes by suggesting that rather than summon eligible princes to Dessau where money was short and entertainments therefore somewhat modest, she should instead be sent on a kind of grand tour of Germany to meet potential suitors on their home turf. The Duchess was delighted. Agnes was devastated.

She was even more horrified to learn that she was to leave for Berlin in a matter of weeks and that she would be chaperoned on this tour by her elderly Great Aunt Caroline, the Dowager Princess of Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt. To Agnes, this would have been the strongest indication yet of just how serious her parents were about finding her a husband in Germany. In the vast majority of cases, aged aunts were engaged to push young princesses in the direction of prospective husbands based on a lifetime of accrued friendships with other dowagers, the whole thing taking place under an illusion of “paying a call” to honour old acquaintanceships. Yet the Duke was not about to marry his eldest daughter off to a minor Prussian prince knowing full well that she was so very much taken with King George V. There was method in his madness and when he put together the schedule for Agnes’ tour, he indicated that no tour would be complete without a visit to the Botanical Gardens at Göttingen.

"Of course, you might consider paying a call on the Viceroy of Hanover about the same time on my behalf, as you will be so close to Herrenhausen..."

Agnes was suddenly very animated and very interested in the Botanical Gardens at Göttingen.

"He won't be there Papa", she corrected him, "The Duke of Cambridge, I mean. There's to be a new Viceroy, the King himself is to oversee the investiture during Hanover Week"

"Really?", the Duke mused, with a wry smile, "You know, I have believed that the gardens at Göttingen should be seen in August..."

Notes

[1] Even though this early attempt at economic sanctions ended in a battle, the use of blockades was a go-to for decades to come with varying degrees of success.

[2] In Scotland, Balmoral always refers to the estate and not the house – whereas in England it’s often the other way around. The reason for this is that until Prince Albert built a new house on the estate in the 1850s in the OTL, the owners of the estate were consistently pulling down and putting up new properties but never to the taste of the next occupant. The Balmoral we know today is possibly the longest surviving Balmoral Castle for some 500 years.

[3] Prince Albert had the same idea in the OTL. A BOGOF deal for Balmoral and Birkhall…

[4] There are other contributing factors as to why the British Royal Family never took to the Duchess of Cumberland but this is the best I can offer as a precis without writing reams!