That is reasonable, I was just worried…This was a tricky one to write because I wanted to avoid that Julian Fellowes "And they all lived happily ever after" resolution. No offence to the creator of Downton there.

Realistically, this is a girl who's had it pretty tough thus far. She didn't know her father at all, she's had no love from her mother and she's probably a little co-dependent on her brother. Understandably so. Her childhood friends (Victoria and Augusta) have gone away and the man she wanted to marry was pushed as far away from her as it's probably likely to get. So she's probably someone who would long for love and happiness but at the same time, I think she'd be prone to lots of self-doubt. She just doesn't want to be hurt again and this marriage means so many new experiences, far away from home etc that I don't think it'd be truthful to have everything be plain sailing for her.

That said, I can offer some reassurance that Charlotte Louise has found her happiness. It'll just take a little time for her to see that as she makes her transition from her old life to the new.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Crown Imperial: An Alt British Monarchy

- Thread starter Opo

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 131 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

GV: Part Four, Chapter Five: Looking Away GV: Part Four, Chapter Six: Brothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Seven: Mothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Eight: An Answer to Prayer GV: Part Four, Chapter Nine: Kings and Successions GV: Part Four, Chapter Ten: Cat and Mouse GV: Part Four: Chapter Eleven: Secrets and Lies GV: Part Four, Chapter Twelve: Life at LissonGreat chapter

I’m glad that Charlotte has finally found happiness despite having a few pre engagement jitters.

Hopefully, the conference at Brighton goes well.

I’m glad that Charlotte has finally found happiness despite having a few pre engagement jitters.

Hopefully, the conference at Brighton goes well.

Last edited:

GV: Part Two, Chapter Nineteen: "No to Weymouth"

King George V

Part Two, Chapter Nineteen: "No to Weymouth"

Part Two, Chapter Nineteen: "No to Weymouth"

As the Russian Tsarevich and the King’s sister brought their romance to its inevitable conclusion, the Duke of Sutherland held court in the Banqueting Hall at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton. The Russian delegation demanded a neutral chairman and at the very last, Sutherland was asked by the King to step in and keep order over the proceedings though Sutherland himself sat with the Whigs in the House of Lords. The talks would last for one week and whilst both parties had agreed to approach these discussions in a spirit of renewed co-operation, the British and Russian delegates had different ideas of what the priority of the conference should be. Both sides had submitted their proposed agendas and finally, it was agreed that that the first session lasting two days should focus on Afghanistan and the situation there since the British retreat at Bala Hissar. A power vacuum now existed and most expected Dost Mohammed Khan to return victorious and proclaim himself ruler once more. The Russians had already made overtures to Khan that he had always had their support and now they offered further assistance in exchange for a clear pathway into the Khanates. For the British, they accepted their presence in Afghanistan had been severely damaged – but they could not yet admit total defeat.

The absence of Lord Cottenham from the talks was a serious blow to the confidence of the British delegates. Whilst he was not a man known for making bold decisions, Sir James Graham had been given the status of an observer. Whilst he could not formally address the meeting, he would be included at the social events which underpinned the talks. It was the perfect opportunity for Graham to further cement himself as the Prime Minister in waiting. When the two sides finally sat down in the Banqueting Hall, sustained by a running cold buffet of pickled herring, pigeons in aspic, beef salad, oysters, sorbets and white wine, the atmosphere was not as constructive as it might have been had the British not taken a severe dent to their credibility in Kabul just a few months earlier. Still, the Foreign Secretary saw this as a chance not only to distinguish himself in his brief but to give a little lustre to his name which might well be considered among the Whig party grandees who may succeed Lord Cottenham.

Lord Melbury.

Melbury had three clear objectives for the conference; 1) To demand the Russians respect Afghan sovereignty and not to use Dost Mohammed Khan as a vehicle to further inflame anti-British sentiment both in Afghanistan and in the Punjab, 2) To secure a permanent British force of peacekeepers in Kabul to ensure they did so and 3) To make it clear to the Russians that despite their shared condemnation of Muhammed Ali Pasha’s adventures in Syria, Britain could only ever join the coalition of the Central Powers in conflict against him as a last resort. Even then, that could not be at the risk of war with France and Spain. Leading the Russian delegation, Prince Gorchakov had his own objectives; 1) To demand the British respect Afghan sovereignty and not to use Dost Mohammed Khan as a vehicle to further inflame anti-Russian sentiment in the Khanates to block further Russian advances in the region, 2) To oppose a permanent British force of peacekeepers in Kabul to ensure the British could not do so and 3) To make it clear to the British that despite their shared condemnation of Muhammed Ali Pasha’s adventures in Syria, only Russia and her Prussian and Austrian allies were taking the threat to Constantinople seriously and that whatever the position of the French and the Spanish, the remaining Great Powers must support the Ottomans against Muhammed Ali.

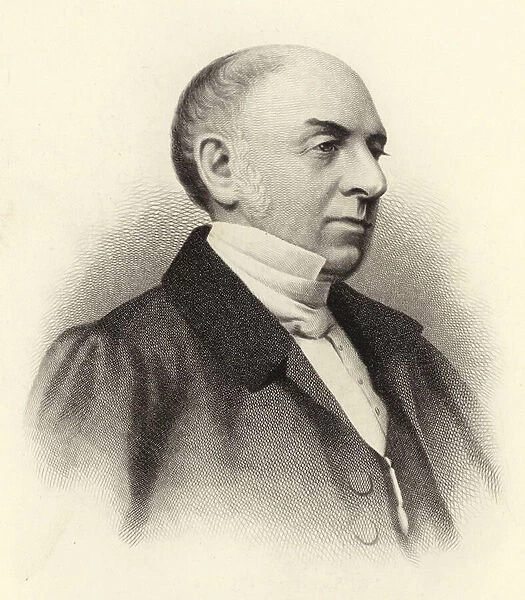

Lord Ponsonby, Britain’s former Ambassador to the Sublime Porte, had been drafted in to support Melbury. This was not just a courtesy because he had spent time in Constantinople (Melbury had too) but because he firmly stood against Palmerston’s approach to foreign policy and favoured diplomatic solutions instead. Indeed, it was Ponsonby who had been dispatched to Buenos Aires in 1826, and Rio de Janeiro in 1828, to gather support for an independent Uruguay which might act as a buffer state between Argentina and Brazil. Lord Cottenham hoped he could apply the same strategy in Brighton. Behind closed doors, Ponsonby had handed Melbury a proposal to put before the Russians. They were unlikely to admit to their trouble making where Dost Mohammed Khan was concerned and would undoubtedly demand that Britain refrain from trying to pull him towards the British side in the Great Game. They would be justified in doing so given that Britain was now in retreat from Kabul and Russia, having committed no troops, was quite entitled to continue to support Khan through aid as they had for well over 25 years.

Britain had not formally recognised Khan as the restored ruler of Afghanistan. He was on the march through the Bolan Pass with nothing to stop him proclaiming himself Emir once more when he reached the site of Britain’s recent humiliation. The United Kingdom could not afford to continue to support a rival and so had been forced to reconsider the Peshawar Agreement which Khan offered before Bala Hissar when the British position in Kabul was stronger. The Tsar was trying to convince Khan to forget all about the agreement, but Ponsonby believed he could play Nicholas at his own game. Russia wanted Britain to respect Afghanistan’s sovereignty. Britain wanted the same of Russia – well, almost. The solution therefore was an agreement to be signed by both countries which forced Dost Mohammed Khan into a permanent state of neutrality. He could not favour one country over another and thus, Afghanistan would become a buffer state.

But Ponsonby realised this would be a hard sell. To sweeten the pot, he suggested the following terms; the first was that Britain’s recognition of Dost Mohammed Khan was conditional on his neutrality, the second was that this neutrality did not apply to trade policy which would be established by a future agreement made at Peshawar, and which would ensure both British and Russian interests were respected. As a gesture of goodwill, the British would continue to send envoys to the Khanates to force the release of Russian merchants taken prisoner and they would support Russian demands that they be free to trade in the region without fear of capture. Ponsonby expected the Russians to demand more. After all, the Russians wanted commercial agents to be given permanent residency in Bukhara and Khiva and free navigation of the Amu Darya, which Britain could not support.

The trump card was troop movement. The Russians were unlikely to accept a British peacekeeping force in Kabul. Neither could the British force such a presence on Dost Mohammed Khan. But if the Russians agreed to the British proposals on Afghanistan, the British would instead move such a force from Kabul and instead station it at Jalalabad. This was hardly a hefty bargaining chip. It would be impossible to station British troops at Kabul anyway after Bala Hissar – unless Melbury wanted to stage another invasion. But Ponsonby saw that by offering this relocation, the Russians could not counter that a peacekeeping force designed to protect British interests in the Punjab was not necessary unless the British had ulterior motives. Ponsonby’s plan allowed the British to keep a foothold in Afghanistan which was not that strategically inferior to their former presence in Kabul.

John Ponsonby, 1st Viscount Ponsonby

Melbury liked what he heard, though it brought to mind the Duke of Wellington’s criticism of the new Foreign Secretary’s reliance on “little scraps of paper”. For two days, the British and Russian delegations examined the Ponsonby Plan. To Lord Melbury’s delight (and surprise), the Russians agreed without hesitation. Their only caveat was that the agreement on Afghanistan was only binding for as long as the British kept their troops at Jalalabad. One step into Kabul and the whole thing would be null and void. Gorchakov smiled. Now came the difficult part. Russia wanted the British to join the coalition of Central Powers in support of Sultan Abdulmejid I. The Ottoman fleet had deserted and now, Muhammed Ali’s forces stood poised to take Constantinople. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire meant the Russians would lose their control of the Dardanelles, something they had fought hard to secure with the Treaty of Hünkâr İskelesi.

This Treaty forced the Ottomans to close the Dardanelles to any foreign warship the Russians did not wish to pass through them. The Treaty had enraged Lord Palmerston, but he was not alone; Austria, France and Prussia were equally furious. Fighting against Muhammed Ali Pasha with the Russians meant (in practise) shoring up a tottering Ottoman Empire which would be indebted to Russia and would undoubtedly honour her treaty commitments with a renewed fervour (even if the Ottomans disliked the Treaty as much as the British). But the British could not afford to let the Ottoman Empire crumble into dust. Nor could it allow Russia to be the primary victor when Muhammed Ali was inevitability forced to withdraw his forces from Syria and accept Ottoman rule in Egypt once more. It was evident that Britain had to take some form of action and the Russians intended that to be a clear declaration of support for the Russian-led coalition. Melbury disagreed.

King Louis-Philippe of France had pledged his support for Muhammed Ali Pasha. He had little choice. The French had just taken Algeria and they wished to expand their presence in North Africa. Muhammed Ali was essential to their ambitions. The question was, how far was Louis-Philippe willing to go to protect his ally? The British government had serious concerns that any conflict in Egypt might spill over into Europe forcing the Great Powers to return to the dark days of the Napoleonic Wars, which the United Kingdom could ill afford. To this end, Lord Granville had been dispatched to Paris to try and make the French see that nobody wanted a war in Europe and that the French were misguided in putting their forces behind Muhammed Ali Pasha in the first place. For the Russians, they saw British involvement as crucial to a swift resolution and swift it would have to be; reports suggested that Ibrahim Ali (Muhammed Ali’s son) was just days away from taking Constantinople.

At the talks in Brighton, Count Nikolai Kiselyov, the Chargé d’affaires from Russia to the United Kingdom, laid out the Russian position. The threat of war in Europe was not unthinkable but the Russians flattered the British with the suggestion that one sight of the Royal Navy on the coast off Beirut would be enough to see Muhammed Ali turn tail and drop his demands of the Sultan. Abdulmejid I would thereafter be dependent on the Great Powers who assisted him and between them, they could carve out new trade routes in the region thereby freezing out their rivals. Melbury was not prone to sweet talk. If Muhammed Ali’s forces took Constantinople, that would quite another matter. Britain would feel compelled to act. But she must act independently if there was even the slightest suggestion that France might declare war on coalition states. Consequently, Britain preferred to see what news came from Lord Granville in Paris and it would then review its position. Melbury favoured sending an envoy to Muhammed Ali Pasha making it clear that he faced a very grave outcome indeed if he took Constantinople. The threat of this alone would make him rethink.

But it wasn’t enough for Prince Gorchakov or Count Kiselyov. They would not return to Russia empty handed and time was of the essence. If the British delayed, the Russians would simply lead the coalition without them and Britain would not be invited to the peace talks thereafter, losing any influence they might have gained with the Ottomans and sacrificing valuable opportunities waiting to be claimed from a grateful Sultan. If France declared war, so be it. The Russians had sent Napoleon packing, Louis Philippe was small fry compared to him. Melbury put forward a compromise; if the Russians could give a written guarantee that it would re-open talks on the future of the Turkish Straits when the Egyptian Crisis was over, Britain would prepare a fleet to send to Beirut. However, that fleet would only be dispatched and engage if the British envoy failed in his audience with Muhammed Ali Pasha or if Ali’s forces took Constantinople, whichever came first. The Russians were not pleased. The Austrians and Prussians had both demanded the same conditions when they signed up to the coalition. The Russian grip of the Dardanelles was looking a little less firm.

Prince Alexander Mikhailovich Gorchakov

The British terms, however, were reasonable. In addition to what Melbury proposed, Ponsonby suggested a further condition that the British would not join the coalition formally but that if the Royal Navy did intervene, the British were to have a seat at the peace talks where the Straits Question was to be discussed. The Russians accepted if this was defined as the Royal Navy having engaged with the defected Ottoman fleet, the intention to send gunboats would not be enough. Melbury thought this to be reasonable, so long as the Russians understood that with Britain not a formal member of the coalition, she would not be expected to join a war against France unless France declared war on the United Kingdom for its independent role in the Crisis. A draft of the Brighton Agreement was put together and the delegates retired to change for dinner. At Arundel, the Tsarevich paced nervously awaiting his carriage to take him to the Pavilion. He had begged Princess Mary to add him to the guestlist. His recent encounters with his intended had left him nervous, not to mention frustrated. Princess Charlotte Louise had seemingly accepted him and yet on the nights in between their talk and now, she wouldn’t even dance with him.

Princess Mary played mediator. On a visit to the Tsarevich at Arundel, she warned him that he must not be too forceful with Princess Charlotte Louise. Mary well remembered just how devastated her niece had been when her relationship with Prince Albert was cut short. When Sasha protested that he had promised always to cherish the Princess, Mary held up a hand to silence him.

“You did not meet her mother”, she snapped, “That woman couldn’t bring herself to display one ounce of love or affection for Lottie. My brother died when she was little more than a babe in arms, her childhood friends have abandoned her, her only experiences of love are fleeting ones built on sand. If you push her too hard, you will force her to turn back. You know…”

Princess Mary began tucking into a toasted tea cake, the butter dripping onto her chin and into the lace frills of her dress as she spoke with her mouthful.

“I married for convenience, not love”, she said wistfully, “A man in your position might do the same. But you have found a girl whom you love, and I believe she loves you. Why else would she bring the box?”

“Box? What box?”

Princess Mary licked the butter from her fingers and heaved herself forward to grab another teacake.

“Oh dear. No jam. How disappointing”, she muttered, “The box dear boy. I gave her something very special to wear if she intended to accept you. And she brought it with her to Brighton. My maid told me so. That means she intends to accept. But if you bully her my dear boy, that box will stay locked up and my lovely earrings will go to waste. Oh really, it is too bad, is there not even a little honey or curd?”

The Tsarevich leaned forward and passed Princess Mary a glass dish full of blackcurrant jam she had overlooked. She broke into a broad grin and began spooning great dollops onto her teacake.

That night at the Royal Pavilion, the guests assembled in what a local publication called “the most glittering occasion since the late Prince Regent first came to love our dear little resort”. The Russians were resplendent in uniforms festooned with medals, the British ladies elegant in silk gowns in vivid blues, reds and greens covered in diamonds. Princess Mary sailed around the room like a well upholstered barge in a dress of bright yellow satin with thick black stripes. One ungallant male guest said it was like seeing an addled bumblebee searching for a flower to doze in after supper. But Mary gave as good as she got that evening. She seemed to take an instant dislike to Sir James Graham and when he approached and began speaking to her at a perfectly reasonably volume, she barked; “You are not in the House of Commons now Sir James, kindly do not shout!”. He further offended her when he dropped a canapé onto the carpet during her conversation (“That was a waste of perfectly good food!”) and then again when he spilt a glass of water at the dinner table (“And now we are all at sea, honestly, that man is all thumbs”). Even Lady Graham did not escape Mary’s criticism. When Lord Barham said he liked Lady Graham’s gown (which was not in any way outrageous), Mary retorted: “Why has she come in fancy dress?”.

Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh

For the first time since his arrival, the Tsarevich had something to smile about. When the doors opened and the royal party entered, there was Princess Charlotte wearing a beautiful pale pink gown trimmed with white lace and studded with little flowers crafted from white plover’s feathers. She was wearing Princess Mary’s diamond and pearl pendant earrings – though the rest of the guests were far more awed by the impressive Oak Leaf tiara which indicated to Princess Mary that her niece had gotten over the worst of her worries. At least for the time being. Immediately after dinner, Mary dispatched a brief note to the King in London; “No to Weymouth”. This was the agreed signal from the Princess to her nephew that Princess Charlotte Louise had accepted the Tsarevich (pending George V’s consent of course) and that Mary would now not be taking the Princess to Weymouth to recover from another romantic disappointment before the baptism of Princess Victoria. The King was instantly put in a bad mood by the note. Though he had slowly come around to the idea, his instinct was still to sulk.

There was another important after-dinner event which is worthy of note. When the ladies left the Banqueting Room to repair to the Saloon, the gentlemen assembled at the top end of the table for port, brandy and cigars. The Tsarevich hadn’t yet had a chance to tell his intended how beautiful she looked but he wouldn’t get one now; Lord Ponsonby collared him and engaged him for 40 minutes, asking what he knew about truffle hunting as he was inclined to try it out for himself by importing both the truffles and a menagerie of pigs from Périgord. Meanwhile, Prince Gorchakov had a more serious mission. He deliberately sought out Sir James Graham, still a little bruised from his clash with Princess Mary. The two men wandered over to a window. Melbury watched from a far, trying to lip read whilst also finding himself engaged in conversation with the Duke of Sutherland who had taken far too much wine at dinner and kept repeating himself.

“I believe it may not be long before there is a change in Downing Street”, Gorchakov said quietly, “Do you expect to win your election?”

Graham smiled.

“I am honoured that my candidacy is so well known in Russia”, he said kindly, “And though I should not like to count my chickens, I do believe we can expect a reasonable chance of a return to government”.

“Count chickens?”

“It doesn’t matter”, Graham shook his head, “I only mean to say that I have every hope I shall soon be in a better position than I am now”

Gorchakov nodded seriously.

“But if you are in that position in a week or two”, he said, almost whispering, “Am I to understand you will honour our agreement tomorrow?”

Sir James Graham nodded profusely; “I can give you that assurance most wholeheartedly Sir. I am here only as an observer, but I believe in this instance I find it easy to support the foreign policy of this government. Not that I should make a habit of that”. He laughed. Gorchakov didn’t. He just nodded sternly and wandered away. The following morning, Graham was informed that he was to act as a witness to the agreement. As an observer, this was quite a usual request but, in this case, he had been asked specifically on the demands of Prince Gorchakov. Whatever happened in the general election, the Russians would not be cheated. Graham was present at the talks, he gave his backing and to that effect, he must now sign his name. Graham had doubts. He sincerely believed that Melbury and Ponsonby had proposed a solid agreement, but he did not wish to be seen approving Whig foreign policy during a general election campaign, even if on this occasion that policy was something the Tories could lend their support to.

Regardless, he signed. The Brighton Agreement, and all it’s conditions, proposals and promises, was signed on the 28th of February 1840. Melbury could return to London with a spring in his step. He had saved the conference and produced an agreement he felt proud of, with a little help from Lord Ponsonby. The Foreign Secretary also returned to London with an idea set in his mind. Cottenham had told the Cabinet that he intended to step down the moment the election result was known. Melbury was 45 years old, and, in his already impressive career, he had served as an attaché to the British embassies in St Petersburg, Constantinople, Naples and the Hague and had also served as the Secretary of Legation in Florence and the Secretary of Embassy in Vienna. His tenure as Foreign Secretary had been brief thus far but he saw no reason why he should not believe his name might be put forward for the King’s consideration. His friendship with George V was likely to stand him in good stead if it was.

A week later, the Royal Family gathered at the Private Chapel at Buckingham Palace for the christening of Princess Victoria. At this time, the Chapel Royal of St James (a more traditional venue for such an occasion) was considered to be out of action because though it had been spared any damage from the Great Thames Flood, the reception rooms were undergoing renovation as a direct result of the ceiling giving way to the excess rainwater. Princess Victoria was therefore the first and last royal baby to be christened at Buckingham Palace. Whilst her younger brother William was christened at St George’s Chapel, Windsor, thereafter all royal children were baptised at St James’. Most were treated to what Victoria’s younger brother Edward described as “the bookends”, being christened at the Chapel Royal of St James’ Palace at the start of their lives and then being returned to it’s walls much later on when the Chapel provided a final night’s rest ahead of their funeral: thus, the chapel served as “bookends” to royal life.

The Christening of Princess Victoria was an intimate affair and because of the General Election campaign, no government minister was invited to attend (usually the Prime Minister at least could expect a place). Also missing from the proceedings was the Tsarevich of Russia. Queen Louise had suggested a last-minute switch of godparents, Sasha being put in the place of her brother Frederick William whom she was sure would understand and could serve as a godfather to her next baby instead. But the King wouldn’t hear of it. He wouldn’t even allow his future brother-in-law to attend the service, though the Queen insisted Sasha be invited to the breakfast that followed. All through this reception, George could not take his eyes off of the Tsarevich; who did he think he was? Strutting about in his finery, flirting with the women and making supposedly witty comments which George certainly didn’t find amusing. As he stood there quietly seething, he felt a hand take his; it was Lottie. She kissed him gently on the cheek and smiled.

“Will you see Sasha now?”

The King looked nervously over to the Queen. From across the room where she was busy bouncing baby Victoria on her knee, she grinned and nodded enthusiastically. He felt his shoulders relax a little.

“Oh, very well Lottie”, he said, but not unkindly, “I'll see him and then you can all stop badgering me about it”

Just a few days later, the people of Britain woke up to two announcements from Buckingham Palace in the morning newspaper. The first was perhaps a little unsurprising. Lord Cottenham had resigned. He would spend the remainder of his days at Crowhurst, returning to London only briefly when he felt a debate in the Lords needed some sound legal precedent explained. When his health declined, he went to recover in the warmer climes of Tuscany where he died just 11 years after leaving office at the age of 70. Cottenham's time at Downing Street lasted for just 187 days, Britain's shortest serving Prime Minister, a record he still retains today. His successor as Prime Minister was Sir James Graham. The Tories had ousted the Whigs from government by slashing their majority in a landslide. The 285 seats the Whigs had won under Lord Melbourne in 1838 had tumbled to just 193 two years later. The Tories claimed victory with 249 seats, the remaining Whig losses spread between radicals, independents and even a handful of Unionists (though Winchelsea was furious not to overtake the Whigs as the official party of His Majesty’s Loyal Opposition).

Sir James Graham

After 9 years of Whig rule, the Tories were back in office. Sir James Graham was summoned to Buckingham Palace shortly after Lord Cottenham departed for the last time as Prime Minister and the King invited him to form a government. It was therefore Sir James who was the first outside of the Royal Family (with the possible exception of Charlie Phipps) to be told the happy news which provided Buckingham Palace with it’s second announcement of March the 15th 1840; The King had given his consent to the marriage of his sister, Her Royal Highness the Princess Charlotte Louise of the United Kingdom, to His Imperial Highness the Tsarevich of Russia. If Graham was taken aback, he didn’t show it. But neither was he particularly enthusiastic.

“I shall put it before the Cabinet Your Majesty”, he said a little nervously.

“No Prime Minister”, the King replied firmly, “You shall inform the Cabinet of our decision”.

Our. George had never used the "royal we" before.

At Marlborough House, Lady Anson helped Princess Charlotte Louise cut the engagement announcement from the newspaper and paste it into a fresh scrap book. Over the next few days, letters and notes from well wishers were all added to the collection until one morning, the Princess asked Anson to bring her a pair of scissors for the day’s additions and was stopped in her tracks by what she saw before her.

When she opened the newspaper, she was confronted with a drawing of a rose garden full of beautiful red blooms wearing tiny coronets. And in the centre of that garden was a huge angry black bear with blood dripping from his bared fangs. He wore a lopsided crown and in his paw, he clutched a rose which was labelled in red ink…

"Poor Princess Charlotte Louise"

Last edited:

I loved this turn of phrase: "Princess Mary sailed around the room like a well upholstered barge..."

As soon as you cast Miriam as Mary I knew she was going to be our comedy relief for politics heavy chapters like this one!Princess Mary coming over all Miriam Margoyles again there in Brighton.

Haha, thankyou! I really do love Princess Mary, she's so much fun to write!I loved this turn of phrase: "Princess Mary sailed around the room like a well upholstered barge..."

Can Princess Mary find the fountain of youth so that she can stay around for the rest of the story?

Ummm....... Indeed, it was Ponsonby who had been dispatched to Buenos Aires in 1926, and Rio de Janeiro in 1928

I think this is supposed to be 1826 and 1828?

Oops! Quite right, many thanks for pointing this out.Ummm......

I think this is supposed to be 1826 and 1828?

I’m glad that Charlotte has accepted the proposal!

I wonder what the cabinet under Sir James will be?

I also wonder what will become of the Irish reforms that Cottenham promised Daniel O’Connell during the vote of no confidence.

I wonder what the cabinet under Sir James will be?

I also wonder what will become of the Irish reforms that Cottenham promised Daniel O’Connell during the vote of no confidence.

A very good observation re: those Irish Reforms!I’m glad that Charlotte has accepted the proposal!

I wonder what the cabinet under Sir James will be?

I also wonder what will become of the Irish reforms that Cottenham promised Daniel O’Connell during the vote of no confidence.

I'll go into more detail about the whys and wherefores but for those following the political side of things...

1838 United Kingdom General Election

1840 United Kingdom General Election

And whilst usually this would come at the end of a chapter when we change government, I'm going to publish it now as whilst I'm hoping to get the next instalment out tomorrow, if I can't then it'll have to wait until next Tuesday (the 17th May) and I never like to make you all wait that long. So consider this a mini-update just in case!

Sir James Graham - First Ministry

Appointed 15th-18th of March 1840

Appointed 15th-18th of March 1840

- First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Lords: Sir James Graham, 1st Earl of Naworth [1]

- Chancellor of the Exchequer: Alexander Baring, 1st Baron Ashburton

- Leader of the House of Commons: Sir William Ewart Gladstone

- Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs: Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby

- Secretary of State for the Home Department: Sir Robert Peel

- Secretary of State for War and the Colonies: Thomas Francis Fremantle, 1st Baron Cottesloe, 2nd Baron Fremantle

- Lord Chancellor: Edward Sugden, 1st Baron St Leonards

- Lord President of the Council: Walter Montagu Douglas Scott, 5th Duke of Buccleuch

- Lord Privy Seal: James Stuart-Wortley, 1st Baron Wharncliffe

- First Lord of the Admiralty: Thomas Hamilton, 9th Earl of Haddington

- President of the Board of Control: Sir Edward Stanley

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster: William á Court, 1st Baron Heytesbury

- Postmaster-General: William Lowther, 2nd Earl of Lonsdale

The Royal Household [2]

- Lord Steward of the Household: Charles Jenkinson, 3rd Earl of Liverpool

- Lord Chamberlain of the Household: George Sackville-West, 5th Earl de la Warr

- Treasurer of the Household: Frederick Hervey, 2nd Marquess of Bristol

- Comptroller of the Household: Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield [3]

- Mistress of the Robes: Charlotte Montagu Douglas Scott, Duchess of Buccleuch [4]

In the OTL he got nothing. He declined a peerage and Queen Victoria loathed him so much she absolutely refused to approve any honour for him. Had Gladstone lived a few years longer, I tend to believe that Edward VII (a close friend and admirer of Gladstone) would have made him a KG. Alas, it was not so. But in our TL George V won't be so cantankerous and so Gladstone gets a royal pat on the head in the years that follow.

[2] I don't usually include these posts as most are hereditary but as this will prove important in the coming chapters, it might be helpful to have a list.

[3] I'm choosing to go with Robert Blake's version of events here. In the OTL, Disraeli wanted a ministerial post but was left out when Peel appointed his Second Ministry. In later years, Disraeli's detractors suggested this was because of the Sykes scandal. Blake asserts this was not the case, rather Disraeli was considered far too junior when compared to the other Tory party grandees Peel had to accommodate.

However, Disraeli is already a member of the Carlton Club by this time, he has the patronage of Lady Londonderry and he's gaining a reputation as a skilled orator. He has also taken all the "right" positions where Graham is concerned. I believe he would petition Sir James for a ministerial post just as enthusiastically as he did Sir Robert Peel. He will have a specific role in mind but other circumstances will prevent him from achieving that dream (not just too many party high ups wanting decent positions from Graham). As a compromise, Disraeli will find himself appointed Comptroller of the Household.

Whilst it sounds a grand post, it's actually quite junior and is the second-ranking member of the Lord Steward's department after the Treasurer of the Household. It was often a post handed out by Prime Ministers to backbenchers who had potential but not very much experience. But it was also used to discourage backbenchers from seeking higher office in the future, the idea being that they would become so attached to life in the Royal Household that they'd wish to stay there and work their way up through the ranks rather than jostle for more senior government posts.

[4] One final thing to note is that we will of course have a new Mistress of the Robes. The Duchess of Sutherland's husband (George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 2nd Duke of Sutherland) was a Whig and so Harriet and the Queen's other ladies in waiting must be replaced. Queen Louise's namesake and predecessor despised such changes in TTL so let's see how her niece and successor handles these departures...

Part Two, Chapter 10

"the Tsar was not a mere constitutional figurehead nor a symbol of an ideal; he was a true Autocrat who believed wholeheartedly that monarchy was a sacred institution through which a divine master plan might be affected" - I see the idea of constitutional monarchy has not reached Russia yet then...

"a happy and loving marriage which had provided him with seven children." - blessed indeed. Nice to find a Royal couple actually in love.

Hope Alexandra get better.

"Charlotte Louise had tried to discuss English literature with Sasha;" - perhaps the Russia had not read any Charlotte? Perhaps exchange books of great literature from each country and compare?

Good luck Sasha - hope it is love indeed.

"This was not the usual weekly private audience between Prime Minister and Sovereign; Cottenham had been summoned." - someone's in Trouble!

Cottenham needs to get food prices and the economy in general under control or the Unionists wills sweep in and noone needs that.

"he much preferred (where possible) to shed official titles and lofty positions when he believed more could be achieved without the complex restraints of court etiquette." - that is a very good attitude, it will certainly help in many private situations.

“I do hope you feel better soon Prime Minister, you do really look so very tired" - doesn't he just....

Part Two, Chapter Eleven

“Because if you deny me this, I will never forgive you. Never”. - Oh dear, you probably want to make up to the Princess, George.

"...the flood water peaked at a level of 14ft above the datum line; six feet higher than the previous record." - Damm that is a Big Flood. Guess the Tower has its Moat again!

"Queen Anne’s Drawing Room was deluged when the ceiling collapsed, though thankfully the Council Chamber survived in-tact." - wonder if the room is restored or rebuilt?

"268 people were reported to be dead; hundreds more were now homeless." - that is indeed bad, esp with the property damage as well.

"Louise ordered her ladies to begin searching the Palace kitchens, cloth stores and cellars for anything that could be spared" - and this is way Louise is so popular.

Fantastic actions from the Earl of Wilton, and Lord Courtenay there- real neighbourly spirit.

"But Cottenham replied that the King must wait." - whoops. Mistake PM.

I wonder if the November Risings will be seen later as the closest the UK came to a revolution?

"George become a heavy smoker of Wills' cigarettes, believing them to be better for him than cigars which he only smoked after dinner from 1840 onwards" - oh dear. That sounds like trouble for later.

"the Tsar was not a mere constitutional figurehead nor a symbol of an ideal; he was a true Autocrat who believed wholeheartedly that monarchy was a sacred institution through which a divine master plan might be affected" - I see the idea of constitutional monarchy has not reached Russia yet then...

"a happy and loving marriage which had provided him with seven children." - blessed indeed. Nice to find a Royal couple actually in love.

Hope Alexandra get better.

"Charlotte Louise had tried to discuss English literature with Sasha;" - perhaps the Russia had not read any Charlotte? Perhaps exchange books of great literature from each country and compare?

Good luck Sasha - hope it is love indeed.

"This was not the usual weekly private audience between Prime Minister and Sovereign; Cottenham had been summoned." - someone's in Trouble!

Cottenham needs to get food prices and the economy in general under control or the Unionists wills sweep in and noone needs that.

"he much preferred (where possible) to shed official titles and lofty positions when he believed more could be achieved without the complex restraints of court etiquette." - that is a very good attitude, it will certainly help in many private situations.

“I do hope you feel better soon Prime Minister, you do really look so very tired" - doesn't he just....

Part Two, Chapter Eleven

“Because if you deny me this, I will never forgive you. Never”. - Oh dear, you probably want to make up to the Princess, George.

"...the flood water peaked at a level of 14ft above the datum line; six feet higher than the previous record." - Damm that is a Big Flood. Guess the Tower has its Moat again!

"Queen Anne’s Drawing Room was deluged when the ceiling collapsed, though thankfully the Council Chamber survived in-tact." - wonder if the room is restored or rebuilt?

"268 people were reported to be dead; hundreds more were now homeless." - that is indeed bad, esp with the property damage as well.

"Louise ordered her ladies to begin searching the Palace kitchens, cloth stores and cellars for anything that could be spared" - and this is way Louise is so popular.

Fantastic actions from the Earl of Wilton, and Lord Courtenay there- real neighbourly spirit.

"But Cottenham replied that the King must wait." - whoops. Mistake PM.

I wonder if the November Risings will be seen later as the closest the UK came to a revolution?

"George become a heavy smoker of Wills' cigarettes, believing them to be better for him than cigars which he only smoked after dinner from 1840 onwards" - oh dear. That sounds like trouble for later.

GV: Part Two, Chapter 20: Rumblings

King George V

Part Two, Chapter Twenty: Rumblings

It was Queen Louise who gave her husband the moniker of "the Ostrich", only partly in jest. When King George V stumbled across something that wasn't to his liking, he simply stuck his head in the sand and pretended it wasn't happening. He would miraculously find overdue papers or pressing issues to be resolved that dragged him away from the real priorities and this was very much the case in the weeks following the engagement of Princess Charlotte Louise. His meeting with his future brother-in-law, the Tsarevich of Russia, was brief and thereafter, he simply wasn't available to meet with him for the remainder of Sasha's time in London. The first excuse was a mercy dash to Windsor where Princess Augusta's condition took a turn for the worst. The ailing daughter of George III was in the final months of her life and had suffered another minor stroke. Then, the King had to prepare the briefing for the redevelopment of Regent's Park for the Cabinet which he wanted Sir James Graham to approve before work could begin. When that was speedily wrapped up (the Prime Minister not being in a position to refuse or reject the proposals as the redevelopment was to take place on Crown land), George V turned his attentions to his friend Prince Alexander of Prussia. In a dreadful state from his over indulgence, the King had sought medical experts to treat him for his growing addiction to alcohol. And when this was put in motion, the King still had other things to do; namely to worry and fret over the appointments being made by his new Prime Minister.

It had been almost a decade since the Tories were last in office and though Sir James Graham and his colleagues celebrated well into the small hours at their victory, there was not much enthusiasm among the general population. The new Prime Minister was inheriting crises on all fronts and the worst of the Winter of Discontent had yet to lift its grim shadow in many poorer areas of the country. To this end, Graham’s first act was to keep his promise and introduce a sliding scale of import duties linked to the overall value of goods. With the cost of a 4lb loaf standing at almost 10d in the inner cities, bakers could (in theory) now take advantage of cheaper wheat and drop their price by around 6d. Graham boasted that this might well see bread prices set at their lowest since 1779 and in theory, he was correct. But in practise, bakers had taken such a financial hit in recent months that most kept their prices high to reimburse themselves for their previous losses. The Prime Minister reassured the public that the prices would fall as the market stabilised but that was little comfort to those facing starvation. It was clear that Graham would need a strong team around him to turn Britain’s fortunes around and from the 15th to the 18th of March, he set about appointing a ministry that combined all talents – but most importantly, which silenced all factions within the Tory Party. Come what may, Graham would not be forced into the same position as his Whig predecessors, held back from taking any steps to ambitious reforms because of in-party back biting.

William Ewart Gladstone, Leader of the House of Commons.

Graham had already composed his new Cabinet long before the election result was declared, the result of weeks of negotiations at the Carlton Club and gentleman’s agreements made at the dinner tables of the great and good of Belgravia. His choice for Chancellor of the Exchequer was Alexander Baring. A prominent financier, Baring had served as a Member of Parliament for over 30 years before finding a place in the House of Lords as Baron Ashburton. But Baring’s appointment was not exactly a reward for long service, indeed, he had never held a government post before. Rather, Lord Ashburton was the biggest financial donor to the Tory Party at this time (unsurprising as he was one of the wealthiest men in England). The son of the founder of Barings Bank, Ashburton's father made his fortune in the slave trade and whilst he had fought passionately against abolition and failed, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer had been generously compensated to the tune of £10,000, the equivalent of £750,000 today, for “loss of assets” in British Guiana and St Kitts. It would be fair to say that Lord Ashburton’s appointment was not entirely based in merit. Upon being asked to appoint Ashburton as Chancellor, George V remarked; "Lord knows he has paid well enough for it".

As Leader of the House of Commons, Graham selected William Ewart Gladstone. Initially a High Tory, he might have been a prime candidate to join the break away of Lord Winchelsea’s Unionists but his loyalty to the Tory party proved more important. [1] His reputation at this time was somewhat tainted by his stances on child labour (he voted against the Factory Acts for example) and slavery. Indeed, Gladstone went to great lengths to guarantee compensation for his father Sir John Gladstone, one of the largest slaveowners in the British Empire. Yet it was his stance against Palmerston’s foreign policy that distinguished him. He was a fierce opponent of the Opium trade and when asked if he might serve as Leader of the House of Commons, Gladstone only did so after reassurance from Sir James Graham that the government would not embark on a war to protect “that infamous and atrocious trade” in the China Seas. But there was an ulterior motive at play in his appointment; Gladstone was a far more liberal voice when it came to Ireland (he was sympathetic to calls for increased self-government) and Graham did not want to have such a skilled orator sniping at him from the backbenches when Graham made clear to Daniel O’Connell that there was no hope that the Tories would countenance the reforms the Whigs had agreed to.

The new Foreign Secretary was the 14th Earl of Derby. Derby loathed Lord Palmerston and he famously described Bala Hissar as “the mill-stone cast around the neck of the Empire by that devil Palmerston”. He was fully supportive of the Brighton Agreement (a caveat which he had to accept if he wished to be appointed to the Foreign Office) and the same was expected of the new Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Sir Thomas Fremantle. The remaining cabinet posts were dished out to the party grandees and their protégés with the Duke of Buccleuch and the Earl of Haddington joining the Graham ministry as Lord President of the Council and First Lord of the Admiralty respectively. But there was a familiar face returning to government in Sir Robert Peel. Though he had been ousted as Tory party leader for failing to push Lord Melbourne from office in 1838, Graham owed much of his success to Peel. He offered Sir Robert the Home Office, never believing he would actually accept the post. But Peel did and though his promotion raised eyebrows among some on the Tory benches, Graham kept his word and brought his former mentor back into government.

There were to be changes too in the Royal Household and this provided the King with yet another distraction. Any senior post held by a Whig (or their spouse) was now considered to be vacant and it was Sir James Graham’s right to appoint Tories to these positions. The new Lord Steward of the Household was the 3rd Earl of Liverpool, the younger half-brother of the former Prime Minister (Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl) who died in 1828, allowing Charles Jenkinson to inherit the Earldom. The new Lord Chamberlain was George Sackville-West 5th Earl de la Warr with the Marquess of Bristol taking up the position of Treasurer of the Household. But the new Comptroller was of great interest to the gossips of Westminster. Graham appointed the 36-year-old backbencher Benjamin Disraeli to the office, against the advice of his private secretary Sir Theodore Williams. Other Cabinet ministers had reservations too, though they expressed them quietly for fear of jeopardizing their own positions at this early stage in a new era of Tory rule.

Benjamin Disraeli had great ambitions but was not entirely well-liked in political circles. He had once stood as a radical candidate, and he held surprisingly liberal views which made him a keen advocate of constitutional reform. He had once been reluctant to support either of the two big parties of his day saying, “Toryism is worn out and I cannot condescend to be a Whig” [2]. But by 1840, that had all changed. With the patronage of Lady Londonderry, Disraeli carved out a niche for himself as a passionate speaker and enthusiastic young Tory who yearned for ministerial office. Yet two things held him back. The first was a scandal which saw Disraeli become the second of two lovers taken by Lady Henrietta Sykes, the first being Lord Lyndhurst, the former Lord Chancellor so recently awarded the Order of the Garter by King George V. It wasn’t the love affair that shocked high society, rather that it appeared Disraeli conducted the liaison solely for the purpose of making introductions to Tory party grandees. This bled into the second barrier Disraeli faced; his Jewish heritage.

Benjamin Disraeli

At the age of 12, Disraeli had been baptised into the Anglican Communion on the advice of Sharon Turner, a solicitor and advisor to Benjamin’s father Isaac. Isaac was not a devout Jew and had faced constant disputes with the authorities of the Bevis Marks Synagogue where the Disraelis worshipped. Whilst Isaac left the synagogue not particularly eager to attach himself to another faith, Turner advised him that it would be better for his children if they (at least nominally) became Christians. Indeed, Disraeli could never have hoped for a political career had he remained an active member of the Bevis Marks. But socially, Disraeli was always going to face the narrow-minded prejudices of those great society hostesses. Antisemitism was rife and just as the Queen’s friend and confidant Reverend Michael Alexander faced prejudice even after his conversion and taking of Anglican Holy Orders, so too did Disraeli [3]. Whilst any other ambitious young Tory would have been congratulated for seeking ministerial office so quickly, the establishment saw things differently in Disraeli’s case; he was simply trying to ingratiate himself with the upper classes for his own financial gain. Though the Queen had set an example by condemning this vile bigotry in her own household, antisemitic views such as these still dominated Westminster and its environs.

Fortunately for Disraeli, Sir James Graham did not hold such views - at least not to the same extent as some of his colleagues. But he did have concerns that Disraeli may prove to be “my Lord John” and to that end, he was not inclined to promote him too quickly. Disraeli hoped for a role as an Undersecretary showing particular interest in the Treasury, but this was unthinkable for Graham who had to accommodate demands from party grandees who all seemed to have very loyal nephews they wished to see elevated given their family’s generosity to the Tory Party’s election campaign. Instead, Graham made use of a vacancy in the Royal Household and appointed Disraeli as Comptroller of the Household. This was a junior post, the most junior ministerial role a backbencher could hold in fact where the Household was concerned, but it did have its compensations. Disraeli would accompany the King and his family to diplomatic and social events, giving him direct (almost daily) access to the Crown. It was often hoped that ambitious backbenchers who were appointed to the post of Comptroller might find a life of royal service far more comfortable than that of a parliamentary career and jump ship to a non-government appointed role in the Royal Household. [4]

But by far the most important change to the household where the King was concerned was the departure of the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland as Lord Steward and Mistress of the Robes respectively. The Sutherlands had been a key part of the Royal Household for many years now, the Duchess in particular becoming one of the so-called “Four Gospels”, her role blurred into that of close family friend and companion and not just the most senior appointee in the Queen’s Household. Longer serving courtiers held their breath nervously. Queen Louise’s aunt and predecessor had always despised the changes made to her household, going so far as to refuse to accept them. With the King seeking any dispute to inflate in order to avoid further discussions concerning his sister's marriage, many feared the Queen might respond likewise. Fortunately, Queen Louise was more practical. When the Duchess of Buccleuch became the new Mistress of the Robes in 1840, Her Majesty welcomed her warmly. She would miss the Duchess of Sutherland (“my dearest Harriet”) but wrote to the Prime Minister thanking him for “such a generous and well-appointed successor in the Duchess of Buccleuch whom I like very much”. But still a clash hovered on the horizon.

Charlotte Montagu Douglas Scott

The Prime Minister made further appointments where the Queen’s ladies in waiting were concerned. Joining the Duchess of Buccleuch were Emma, Countess of Derby and Maria, Countess of Haddington. Maria brought with her Lady Ellen Fane, her cousin and wife of Colonel John Fane whom the King invited to join his Household as an Assistant Private Secretary to Charlie Phipps. The final appointment was to be Lady Selina Fremantle, the sister-in-law of Sir Thomas Fremantle, the new Secretary of State for War and the Colonies but this proved to test just how different to her predecessor the Queen was. The Prime Minister wished to appoint Lady Selina as a replacement to Lady Dorothy Wentworth, she being the daughter of the Whig 5th Earl Fitzwilliam. Dolly was in Bautzen as de facto head of the Princess Royal’s Household and naturally Sir James believed he had a perfect right to expect her to leave royal service given her proximity to a rival party. But both the King and Queen were horrified at the suggestion. They were adamant that Dolly was to be exempt from any changes made to the Royal Household. The Queen insisted that Dolly was not a courtier, rather she was the Governess to the Princess Royal and could not be removed from that post as it was not traditionally considered to be a post the government had a hand in.

However, Sir James Graham was not fully aware of the circumstances surrounding Missy’s removal to Germany. He had also made a promise that Lady Selina would be given a post in the Royal Household and he felt that a post in the Princess Royal's Household (for that was how the nursery at Bautzen was referred to) now came into the government's purview. To that end, he wrote a letter to the Queen insisting that Her Majesty; “be reassured that I have no great desire to disrupt the household of Her Royal Highness the Princess Royal, but that the convention which allows me to make such appointments has long applied to all senior members of the personal households of members of the Royal Family and an exception cannot be made for Lady Dorothy Wentworth”. The Queen did not need to protest to her husband, he was in full agreement. Reports from Leipzig concerning the Princess Royal were positive. She had settled well and was “in all ways a most happy and contented child”. Princess Augusta of Cambridge wrote of Lady Dorothy; “She is quite devoted to Missy and Missy to her; indeed, Dolly has taken it upon herself to attend some of the classes at the college which teach adults how to speak with their hands for if this is to be the only remedy to poor Missy’s condition, Dolly intends that she should be fluent in this most fascinating skill”. That progress could not be disrupted now.

At their first audience following Sir James’ appointment, the King put his foot down. Dolly was a non-negotiable presence in his daughter’s life and the King would not, and could not, contemplate her replacement. But as a concession, the Queen had invited Lady Selina to join her own Household as a lady of the bedchamber.

“But Your Majesty, that is not the point”, Graham objected, “I understand that Lady Dorothy is a friend of Her Majesty’s and no doubt greatly loved by the Princess Royal, but she is also the daughter of a Whig peer...”

“Who lives in Germany now and cannot possibly exert any political influence”, George countered brusquely, “I am sorry Prime Minister, the Queen and I must insist upon this. We have been content to see some of our closest friends leave our Household with the change of government, I have also given you some assurance that we shall curtail our connections to Lord Melbury and the Sutherlands but that must be the sum of it. Lady Dorothy must remain in her post".

Sir James bowed to royal pressure. He did not intend to start his premiership with a clash with the Crown and however reluctantly, he accepted that Lady Dorothy must be allowed to keep her post. Lady Selina Fremantle joined the Queen’s Household instead but only briefly. She bored of court life easily and asked to be relinquished from the Queen's service. Graham's decision on this appointment would have a long-standing repercussion in that, whatever post she enjoyed in the Royal Household, “Aunt Dolly” always fell outside of the usual political appointments to the Household. She would never be threatened with removal again and thus, she would ultimately achieve seven decades of royal service under Prime Ministers of all political banners. The disagreement over appointments was forgiven and forgotten, though Sir James still didn’t know why the Princess Royal was in Germany beyond what the public had been told; she was recovering from an infection of the chest. He did not pry, rather the Prime Minister hoped that eventually he would win just enough royal trust to be told the truth.

That first audience between King George V and Sir James Graham naturally focused on the Tory priorities of their first 100 days in government. The King praised the Prime Minister for his swift action on pricing and hoped that food shortages and spiralling prices could be further curtailed in the coming weeks. But there two other issues which threatened to make the meeting a little more tense. It must be said that the King later came to like and respect Graham but in these early days, he was wary of him. As a young man, the King had come to know the same familiar faces at his court, and he had allowed a certain degree of familiarity. He was not yet inclined to do so with Sir James who struggled in his first year or so as Prime Minister to gain the Royal Family’s trust. Still, Graham did not take this personally; “I accepted that for His Majesty, the change of government of 1840 meant a wholesale replacement of those closest to him and this he had not yet experienced. Therefore, I was respectful of this and did nothing to push the King to accept things he might find disagreeable".

The first issue which delayed the two men forging a better working relationship was the Prime Minister’s response to the gazetted engagement of Princess Charlotte Louise to the Russian Tsarevich. The Cabinet had been briefed that the King had given his consent and that now, negotiators were to be appointed to begin preliminary discussions of the marriage contract. The Russians were well ahead on this but were insisting that the talks be held in St Petersburg, not in London. The Tsar and his wife were far more enthusiastic about the match now that it was official, though the King was still a little shellshocked. The Tsarevich would spend another month after the Brighton talks in England where he could (with a chaperone) spend more time with his intended before his return to Russia. Sir James stressed that whilst the Cabinet was united in its desire to see the King’s sister happily married to the man she loved, the engagement had not been received with the usual outpouring of public affection one might expect and many in high society had reservations. Russophobia still ran deep, and the worries Lord Cottenham’s ministers had expressed were shared by the new intake. The King let his frustration get the better of him.

“For heaven’s sake man”, he snapped, “I have made it abundantly clear that there is to be no political connotations to this marriage, I have given my word on that, and I have been assured that every possible objection can be countered with a practicable solution. I cannot do more”. Whilst his sister's engagement had filled the King's mind for weeks, he had overlooked the fact that for Sir James, this was new territory.

“But with respect Sir”, the Prime Minister replied, “Those assurances were given to my predecessor. I have no idea of what was previously agreed, and I must be able to return to the Cabinet with some guarantee that every step will be taken to ensure this marriage has no diplomatic or dynastic consequences”.

“Is the King’s word not good enough?”

“Your Majesty”, Sir James reasoned, “I ask only that we be privy to the agreements made with my predecessor, agreements I am certain my colleagues will respect. But I cannot make appointments for negotiators as Your Majesty asks of me unless I know what has already been agreed...”

“Oh, damn it all!”, George barked, “I shall have Charlie send you a briefing, I am sick to the back teeth of this marriage before it’s even begun.”

Sir James decided to try another angle.

“I can understand that Sir”, he replied kindly, “It must be of great concern to Your Majesty, and if I may, I know that you will feel the departure of the Princess very deeply. But I am here to assist Sir, not to challenge. There are things I must know now if I am to provide that assistance. For example, should the government expect Your Majesty to appoint a deputy of some kind whilst you are in Russia” [5]

“In Russia?”, the King was startled, “Who said anything about my going to Russia?”

“For the wedding Sir”, Sir James replied, “Naturally I would have expected to have met with the Duke of Sussex during Your Majesty’s absence, but I understand His Royal Highness is now retired from service and I- “

“I shan’t be absent!”, the King protested, “My sister shall be married at St George’s, just as I was. Russia indeed. Oh, damn it all, can’t we move on to something else?”

The Prime Minister had unwittingly addressed something the King had not considered. The Tsar was insistent that his son and heir would marry in St Petersburg. As Charlotte Louise would one day succeed her mother-in-law as Empress consort, it was unthinkable that she should not be married on Russian soil. But the King had assumed she would marry in England, perhaps with a service of blessing in her new homeland after her arrival as the Tsarevich’s wife. He was sorely mistaken. This was not a battle he could win either, Princess Charlotte Louise had already discussed the venue for her marriage with her fiancée and she understood the importance of her being married in Russia even if her brother did not. Sir James silently reorganised his papers and moved on. He could tell the King’s patience was wearing thin today yet there was one more subject he must raise urgently.

“There is a matter I must bring before Your Majesty”, he continued, “Which I have to say I wish I did not. It concerns the House of Lords. As Your Majesty will no doubt be aware, my majority in the Commons will be dependent on support from Unionist members from time to time but we have every expectation that our programme shall be implemented relatively easily. But in the upper house Sir, the appointment of Whig peers during the regency put my party at a disadvantage. The creation of yet more Whig peers since 1832 gives them a huge majority in the Lords. That is something that my party must balance out if we are to govern." [6]

“Balance out?”, the King replied, somewhat confused, “Why?”

It was now Graham’s turn to express his frustration, though he did it politely.

“Because I cannot deliver the bills in Your Majesty’s upcoming speech unless my party has a working majority in the upper house as well as in the Commons Sir. Every bill we pass through the Commons shall be rejected by the Lords by a staggering number we could not hope to overturn with the usual annual elevations. Therefore, I must ask Your Majesty to create new peers to- “

"No Prime Minister!”, the King bellowed, “Absolutely not Sir! My Uncle should never have given into those demands before; he always regretted it. I shall not be swayed on this. To get you a majority I should have to create dozens of new Tory peers and then what? Your successor would ask for dozens more, there wouldn’t be enough room for them all. Everybody but the tinker and the tailor would be swanning about in ermine. No Sir James, I’m sorry but you must find another way”.

The Prime Minister stood up slowly and gathered his papers together.

“Your Majesty”, he began tersely, “I am afraid there is no other way. I share your view that the creation of so many Whig peers was a mistake, but it is a mistake that has been made and must now be rectified. I shall ask my Private Secretary to submit to Your Majesty the new creations I am seeking, and I can reassure you Sir that I shall look into further measures to prevent the House of Peers from swelling further in the future. I bid Your Majesty a good morning and if you will excuse me Sir, I must attend a committee concerning the proposals for the new Palace of Westminster”

And with that, Graham bowed and left the King’s Study. Charlie Phipps entered the room slowly. The Prime Minister had left 25 minutes earlier than planned. The King lit a cigarette and slumped into his chair at his desk. He had hoped a change of government would ease his workload, not increase it. He had perhaps underestimated Graham. Whilst Lord Cottenham was easier to push into a direction George felt more comfortable with, his successor was not to be driven so easily. Charlie cleared his throat tentatively. He knew all too well that the King was quick to temper when he was in such moods.

“Your Majesty, I have a message for you from the Queen”, he said softly, “She regrets that she has a slight head cold and asks that you understand she cannot accompany you to the theatre this evening”

“Oh, it’s too bad of her Charlie, really it is”, George whined, “After the day I’ve had too. I was looking forward to that. Very well, send Allison and I shall go and see her after lunch. And for God’s sake send a message to Melbury will you? He can bring his wife with him...”

“Sir…” [7]

“Ah. Of course. Well in that case, invite Prince Alex, he's back from Windsor now isn't he?”

Charlie felt he was dancing a tarantella on eggshells.

“Your Majesty, Prince Alex left the Fort two days ago for Surrey”.

“What the devil is he doing there?”

“Shooting I believe Sir, though I understand he was not very happy. Lady Manning did not extend an invitation to Frau Wiedl”.

The King shook his head. “Damn snobbery”, he muttered. “Where is she now?”

“I believe she is staying at Brown’s on Albermarle Street. They say it’s really quite comfortable, for an hotel”. [8]

“Well that fixes that then Charlie, ask Rosa along would you? We'll take supper at the theatre. And let’s have Manso and yourself along too, what? Make a party of it”.

The summer of 1840 would see a change in the King’s relationship with Rosalinde Wiedl and one which has led many historians over the years to puzzle over the true nature of their association. Eventually tired of Prince Alexander of Prussia’s excessive drinking and gambling, Wiedl began to spend more time in London as he gadded about England being hosted by obsequious aristocrats on their country estates who loved nothing more than adding a Prince to their guest list - however badly behaved he was. But most would not be as generous to Frau Wiedl as the King and Queen were and she got bored of being left out. By September 1840, Prince Alexander’s physical relationship with Wiedl ended, though they remained close friends. Instead, Rosalinde became a regular at court Queen Louise went to great lengths to include her in the royal social calendar. Her Majesty genuinely seems to have enjoyed the company of Frau Wiedl but perhaps by keeping her close by, she was also trying to prevent any gossip or scandal at court by making it clear that Rosalinde was a friend to both the King and Queen. If Frau Wiedl (known to the Royal Family as Rosa) attended a ballet or a dinner with George, it was always with Louise’s knowledge – and blessing. But what exactly was the motivation behind this arrangement?

Some historians insist that this was a classic ménage à trois, the Queen accepting the King’s new mistress into her home and showing her kindness and extending the hand of friendship to keep the peace. Such niceties were not observed during the reign of George V’s father; George IV's affair with Lady Elizabeth Somerset had not been taken well by the Dowager Queen Louise and is arguably what began her on a downward path which saw her eventual confinement at Kew and her prolonged estrangement from her son. These same historians believe that precedent suggests that George was intimate with Wiedl, at least for a time, and that the Queen simply accepted this as extra-marital affairs in royal circles were not only tolerated but expected. They consider it naïve to believe that such a relationship could only be platonic and that a handsome King in his early 20s would not have a roving eye for a pretty lady, especially given that George V liked the company of women slightly older than himself who mothered him – as Wiedl undoubtedly did.

Rosalinde "Rosa" Wiedl.

History records Wiedl as a royal mistress, yet technically this was not true in the case of Prince Alexander of Prussia and neither can it be proven so regarding King George V, at least not in the early years of their friendship. Prince Alexander was not married after all and however unsuitable she might have been from his parent’s point of view, Wiedl was Alexander’s companion and lover and not his mistress. Their physical relationship is well documented but where George V was concerned, friends, confidants and courtiers who served the Royal Household took great pains in later years to stress that the King was always faithful to his wife. He couldn’t be anything else. His love for her was intense, he was often overprotective of her interests, and it is doubtful that he would ever break his marriage vows to her. The fact that the Queen welcomed Wiedl openly as a friend might suggest she was generous of spirit, that she turned a blind eye to her husband’s dalliance as many of her predecessors had when their husbands found it impossible to resist the charms of a pretty girl. But it is widely accepted that this was not the case. The Queen simply liked Wiedl. She had nothing to fear from her. She trusted her husband implicitly and there is no evidence that there was any hint of a physical relationship between the King and Frau Wiedl at this time. Their relationship was described by Charlie Phipps as being “more like siblings, especially after Princess Charlotte Louise left England”.

Whatever it’s true nature however, in the summer of 1840 Frau Wiedl accompanied the King on fourteen separate occasions when his wife was not present. It wasn’t that the Queen disliked society or (as her predecessor had) was turning away from public appearances. On the contrary, following the birth of Princess Victoria, Queen Louise threw herself into her work with a renewed vigour, ever mindful that her mother-in-law had earned the ire of the British public for her failure to go amongst them. Queen Louise opened hospitals, she attended bazaars, she visited museums and galleries, she even visited a workhouse in Bethnal Green in June 1840 against all advice; “I have nothing to fear from the poor”, she said, “I am going as their friend, not as their Queen”. This was certainly how the public came to see Queen Louise. The new royalism owed much of its enthusiasm to her and when the King attended the State Opening of Parliament in March that year, the Queen accompanied him – something her mother-in-law had never done during the reign of George IV. She was openly cheered as her carriage passed by the crowds and one man was reported as presenting her with a dozen white roses as she left Westminster Hall. [9]

On this occasion, the King added something unusual to the end of the address, announcing in person before the assembled Lords and Commons that “We have been pleased to give our consent in-council to the marriage of our well-beloved sister, the Princess Charlotte Louise”. But he did not say to whom she was now engaged. Neither did the King visit Marlborough House which he would soon come to describe as “Little Russia” because of the endless parade of delegates, courtiers, advisors and tutors who were sent to England by the Tsar and his wife to help prepare Princess Charlotte Louise for her marriage. As much as she tried, the Queen could not force the King to address the situation head on, though the mild-mannered "Sunny" broke her placid disposition around this time when the King said he couldn't possibly go to Marlborough House because he had to attend to something very important. When the Queen called in to the study, she found him colouring in little diagrams of footmen and carriages. He was unhappy that some of his aunts and uncles were using the red and blue colours of his livery and the light brown of the royal phaetons. He had decided therefore to give each household new colours to use; the King and Queen retained gold, red and blue, the Cambridges had gold and green as Viceroys of Hanover, the remaining brothers and sisters of his late father were to use silver and navy blue and as for coaches, the King and Queen would adopt maroon with the Cambridges allowed to use light brown and all other family members permitted only to travel in carriages painted in light grey. Insignia for the royal couple would be painted on the carriages in gold, everybody else (including the Cambridges) must make do with silver.

"Oh Georgie, really!", the Queen exclaimed, "And this is why we could not dine with Lottie and Sasha tonight?! Oh you really are too silly. I shan't travel in any carriage with you so long as you keep up this behaviour. Well you may please yourself, I am going to dine with them tomorrow evening and you can sit here all by yourself playing with your silly drawings".

The King blushed. He was not used to be admonished by his wife. And he knew she was quite right too.

At Downing Street, Sir James Graham was carrying on regardless. He compiled his list of nominated peers with his secretary Sir Theodore Williams and at his first Cabinet meeting, passed on the King’s assurances that the upcoming marriage of Princess Charlotte Louise would not be a political or dynastic union but simply a private love match. The new Foreign Secretary, Lord Derby, was unconvinced but he agreed with the Prime Minister to wait and see what Charlie Phipps' briefing contained. Nonetheless, Derby still appointed three junior ministers from the Foreign Office to lead the marriage negotiations for the United Kingdom, but he warned them that the King was likely to make heavy weather of things. Yet at least the Russians would not be quite so boisterous, he predicted. The Brighton Agreement had opened new possibilities in the Anglo-Russian relationship and Lord Derby was certain that the Russian enthusiasm for the Agreement might make the marriage contract from their side far less stressful than it needed to be. That was to prove easier said than done.

It was with this positive outlook in mind that a cheery Lord Derby left the Cabinet Room at Downing Street to head back to the Foreign Office. An urgent memorandum awaited him. News had come from Egypt, yet unconfirmed, that Muhammed Ali Pasha had just been deposed by his son and heir, Ibrahim Ali – and it appeared the British may be partly responsible. Now ousted from government, Lord Granville had done much to reassure the French that Britain did not seek a war in Europe. The French were still not prepared to abandon Muhammed Ali Pasha, they remained committed to his cause – yet rumours swirled that the French government had reviewed their position and the military support Muhammed Ali Pasha was counting on was likely to experience “delays”. Ibrahim Ali had never trusted King Louis Philippe to provide the assistance he promised in the first place and these rumours only spurred him to act quickly. Constantinople was in his sights yet his father would not advance. Whispers were everywhere. If Muhammed Ali Pasha was deposed peacefully, perhaps by a family pact, Ibrahim Ali could succeed and force the Ottomans into a corner securing the greatest possible future for the Ali dynasty with Constantinople as a bargaining chip. [10]

It appeared those favourable to such a plan had just acted on Ibrahim Ali's behalf. Lord Derby turned pale and asked for a glass of brandy.

“Do you hear that Curzon?”, he asked his private secretary.

“No Sir?”

“It is the rumblings of war Curzon. The rumblings of war”.

[1] Gladstone was a High Tory in his early career but slowly embraced a more liberal point of view over the years, as did many of his contemporaries. At this time, he's still very much a passionate Conservative of the Peelite tradition.

[2] An actual Disraeli quote.

[3] You can read more about Alexander (and the social attitude towards British Jewry at this time) here: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...british-monarchy.514810/page-24#post-22962729. Once again, I stress that these are historically accurate views expressed in the 1830s and 40s and ones I find repellent.