I too am happy to have nominated you, because your story is the first one that grabs me and manages to always keep my expectations and curiosity in each of your updates. in a nutshell I liked the other stories I read but then they diminished for me while this is the exact opposite I didn't think that a story about yet another English or British monarchy fascinates me so much plus your extras about other countries they are fantastic and always well prepared.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Crown Imperial: An Alt British Monarchy

- Thread starter Opo

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 131 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

GV: Part Four, Chapter Five: Looking Away GV: Part Four, Chapter Six: Brothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Seven: Mothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Eight: An Answer to Prayer GV: Part Four, Chapter Nine: Kings and Successions GV: Part Four, Chapter Ten: Cat and Mouse GV: Part Four: Chapter Eleven: Secrets and Lies GV: Part Four, Chapter Twelve: Life at LissonP.s. on Vienna and Italy, when eventually they will be part of the story, know that I will comment on the issue with great will, this does not mean that I will not do it for other topics that will come out of your storyI too am happy to have nominated you, because your story is the first one that grabs me and manages to always keep my expectations and curiosity in each of your updates. in a nutshell I liked the other stories I read but then they diminished for me while this is the exact opposite I didn't think that a story about yet another English or British monarchy fascinates me so much plus your extras about other countries they are fantastic and always well prepared.

Last edited:

GV: Part Four, Chapter Two: Beyond the Palace

King George V

Part Four, Chapter Two: Beyond the Palace

Part Four, Chapter Two: Beyond the Palace

At his Palace in Kabul, the 53-year-old King Mohammed of Afghanistan was on sparkling form as he entertained a delegation of Russian investors in great style. Surrounded by a vast number of his dynasty (the King had 27 sons and as many as 50 brothers), His Majesty was bound by the custom of melmastyā to show profound respect and extravagant hospitality to any visitor to his court regardless of their race, nationality or religion, a practise much admired abroad. The British Lord Elphinstone observed in 1815 that “this virtue is so much a point of national honour that their reproach to an inhospitable man is that he has no Pashtunwali” and this was somewhat taken advantage of by wealthy Russian merchants in particular who considered that whilst visiting their concessions in Kabul might be laborious, the King’s generosity more than made up for the hassle of the journey. Of course, King Mohammed was not entirely driven by the obligation of timeless tradition. He owed much to the Russians who had not only helped to restore him to his throne but who had also secured his own personal comfort and prosperity with a series of very generous financial gifts. Indeed, many who visited the Royal Palace at Kabul nicknamed the complex “The Tsar’s House” because it was Nicholas I who personally funded it’s construction in one of many gestures of friendship which helped to secure Russian dominance in Afghanistan from 1842 onwards.

However, Russian money was not enough to keep trouble from King Mohammed’s door. When he was brought back from his exile and proclaimed Sovereign once more, he returned to a fractured Kingdom riven by tribal divisions, the leaders of these tribes having supported the British, the Durrani Shahs or even candidates from within their own ranks as the rightful holder of the Crown which King Mohammed now called his own. Bending to this pressure and seeking to consolidate his authority, Mohammed convened a special council which attempted to bring all tribal leaders together regardless of past affiliations or allegiances and though he demanded a declaration of loyalty in exchange for a seat on the council, most were willing to give it as their ambitions were tamed by circumstance. Yet by 1845, the council itself had become a weak and splintered body with the authority tied up in the hands of three key players in the Barakzai dynasty. Naturally the King himself held the lion’s share of power but he was ably assisted in this by his brother, Sultan Mohammed Khan and by his son, Akbar Khan. Akbar Khan was not the King’s eldest son yet he had so proved himself on the battlefield that he was marked out from the ranks of his siblings to be appointed Wazir. Everybody fully expected Akbar to succeed his father in time and so more often than not, the council demurred to his position well aware that Akbar may dispense with their services when he took the throne. Equally, Sultan Mohammed was one of many royal siblings but he was greatly trusted by his brother and many felt that the best way to the King was through the Sultan. Remarkably, there was no great struggle for power between uncle and nephew, indeed they shared a common goal which in 1845 became all encompassing to their interests. Furthermore, they were prepared to go to war to achieve this united ambition.

King Mohammed of Afghanistan.

Until 1818, the city of Peshawar and it’s surrounding valley had fallen under the control of Afghanistan and was administrated by none other than Sultan Mohammed Khan as it’s Governor. This bustling centre of trade and commerce was not only an economic advantage but a source of national Afghan pride too for it marked a victory of the Afghan people over their great rivals, the Sikhs of the Punjab. But this conquest proved to be short lived. In 1818, the Sikh Empire’s Maharaja Ranjit Singh marched into Peshawar, captured it and within twenty years the city was annexed into Sikh territory. Sultan Mohammed was ousted and replaced by a new administrator. Curiously this Governor was an Italian soldier, Paola Avitabile from Naples, who quickly set about unleashing a reign of terror on the Muslims of Peshawar. Mosques were desecrated and/or turned into Gurdwaras, summary executions were commonplace and this period in the city’s history was to become known to history as “the time of gallows and gibbets”. More inclined to play ruler than to secure stability or even prosperity, Peshawar’s glory quickly declined. In 1837, the Afghans attempted to take back Peshawar, their armies led by Akbar Khan – but they failed, a source of personal regret and humiliation to the man who would be King. It was this skirmish between the Afghans and the Sikhs which first inspired Lord Palmerstone to consider intervention in the region which ultimately led to the British defeat at Bala Hissar which saw the Barakzai’s restored to power in Kabul. Now feeling secure in their position, Sultan Mohammed Khan and Wazir Akbar Khan wanted to right the wrongs of the past and finally take back Peshawar.

Since their humiliation in 1842, the British had been forced to accept a rebalance of foreign influence in Afghanistan. Many British traders could no longer make their concessions profitable and had to abandon them, instead heading into other outposts where they stood a better chance of trading free from trading restrictions or worse, from the threat of violence. At first, many headed for Peshawar but this proved disastrous when in 1843, the East India Company annexed Sindh to the south of the Punjab and in retaliation, British concessions in Peshawar were attacked. The British traders did not press their interest, after all they could always head to the Sindh itself which was now “under British protection” but by 1845, the tensions between the Sikh Durbar and the East India Company reached such a pitch that diplomatic relations were officially broken and the Company began to move its army to Ferozepur under the auspices of Sir Henry Gough. The seeds of the Anglo-Sikh War had been sewn but in Kabul, the Barakzais looked on with interest as they saw a window of opportunity. Sultan Mohammed and Wazir Akbar knew that the British would, if victorious, claim Peshawar for their own. In their view, the Sikhs were a common enemy and it made perfect sense to aide the British in Peshawar for the ultimate concession of the city. But when they took this proposal to King Mohammed, he refused to hear them. [1]

Since 1844, the King had faced a daily struggle to control the territory he already had beyond his capital. There was a myriad of internal battles among tribal leaders, most notably with Yar Mohammed Khan who had taken control of Herat in 1842. Yar Mohammed wanted to expand his territory with a particular interest in Balkh, which the Emir of Bukhara had pledged to assist him with. This first came to the attention of King Mohammed courtesy of the Mir Wali of Khulm, a supposed ally of the Emir but who did not wish to see Yar Mohammed’s ambitions realised. He claimed that Yar Mohammed’s sights were set well beyond Balkh to Kabul itself which led King Mohammed to order a pre-emptive attack on Balkh to occupy it before Yar Mohammed had a chance to seize the city for himself. This would negate war between Herat, Bukhara and Khulm but the Mir Wali was not convinced. He saw that he had far more to lose than King Mohammed and said that he could not agree to the King’s proposed course of action. The King then suggested that military intervention may not be necessary if the Mir Wali would accept an Afghan governor in Khulm. Again, the Mir Wali refused. Seeing that the King of Afghanistan would only help if there was something in it for him, the Mir Wali returned to Khulm and ordered that the name of Emir Nasrullah Khan of Bukhara be read in the Khutbah, in other words, he defected. Now King Mohammed had the casus belli he needed to invade Balkh.

The problem was that the assault on Balkh did not go as smoothly as King Mohammed had hoped. Beset by dynastic wars and constant defections on all sides, soldiers often did not know which Khan they were fighting for or why. Mutiny was common place and this was made worse by outbreaks of cholera and even plagues of locusts which ravaged the crops and left the people starving. Many sold their children into slavery to afford basic provisions and it seemed that nobody could make the final push needed to beat back Yar Mohammed or see him victorious. The situation was confused and bloody but as things progressed throughout 1844, slowly but surely Yar Mohammed managed to convince other tribal leaders to join him. King Mohammed panicked and played his trump card; he appealed to Russia for help.

The Russians had long been waiting for this, in truth it was the only reason they had ever backed King Mohammed at all. Yar Mohammed was backed by the Emir of Bukhara, Bukhara was much coveted by the Russians and their previous attempts to seize it had not only stalled but had inflamed tensions among the Great Powers in Europe who sought to curb Russian influence in the region. Now they had a perfectly reasonable (and legitimate) cause to intervene. Russia’s ally was in trouble. She had a moral obligation to ensure peace and prosperity in Afghanistan. But this made Sultan Mohammed and Wazir Akbar extremely unhappy. Whilst they appreciated the pressing concern that Yar Mohammed had set his sights on Kabul, they knew they were about to miss their window of opportunity to reclaim Peshawar. King Mohammed refused to countenance any assistance for the British because it would allow them to rebalance things in the so-called Great Game – which was certain to upset the Tsar. Without the Tsar’s help, the King may not be able to keep control of his Kingdom and he simply could not face the ignominy of being deposed and exiled again. His answer was clear; Peshawar was a distraction. He must present a plea to the Russians and accept whatever terms they may present to ensure that Yar Mohammed was defeated. If that meant total Russian control in Bukhara, so be it.

In London, the Foreign Office was more interested in troop movements of the Bengal Army ahead of what would inevitably turn into all out conflict with the Sikh Empire. Since the death of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in 1839, the Empire had tumbled into chaos and within months, a power vacuum emerged when Ranjit Singh’s successor, Kharak Singh, was poisoned. His son, Kanwar Nau Nihal Singh, was then proclaimed Maharaja but again, within months he was dead following an “accident” at the Lahore Fort when an archway fell on him. Two major factions were borne of this nightmare: the Sikh Sindhanwalias and the Hindu Dogras. To maintain a balance of power, the Crown went to the Sindhanwalias but the office of Prime Minister went to the Dogras. Britain watched on with great interest as executive power and civil authority began to weaken. When the army rebelled in 1843, Maharajah Sher Singh was murdered which began a bloody civil war at the Durbar that saw brother turn on brother until the infant Duleep Singh was proclaimed Maharaja. With the ruling dynasty distracted by internal divisions, the British were able to establish a military cantonment at Ferozepur and in 1843, as we have already seen, this allowed the British to seize the Sindh. The East India Company continued to increase troop numbers until the Sikh Empire got the message; war was now inevitable.

The Foreign Secretary, Lord Morpeth, found it incredibly easy to introduce the concept of this war to a fractured parliament because MPs of all sides were only too willing to believe that the British were doing the right thing in relation to their interests in India. Indeed, even those who had been rather dismissive of the capture of the Sindh now claimed that they had never really felt that way and the British had every right to secure their existing territories in the region in the face of Sikh aggression. But when it came to Afghanistan, opinions were bound to prove even more divided. It must be remembered that many associated the British defeat at Bala Hissar with the Whig party itself – arguably it was this that led to their ousting from government in 1840. Now back in office, the last thing the Whigs needed was for the spectre of that particular humiliation to rear it’s ugly head and yet it did so in August 1845 thanks to a former member of that self-same government that saw control over Afghanistan as essential to Britain’s prospects in the Great Game; that Whig statesman was none other than Lord Palmerston.

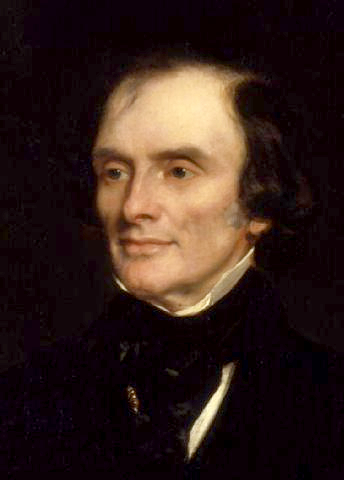

Lord Palmerston.

Back in 1838, Palmerston (as Foreign Secretary) wanted to see Britain enter into negotiations with the then Dost Mohammed Khan and his chief backer the Qajar Ruler of Persia to form an alliance against Russia, thereby curbing her influence in Afghanistan and the wider region. But Dost Mohammed Khan and the Persian Shah had already entered into negotiations of their own (ironically forming an alliance against the Sikh rule in the Punjab) and wanted no part of the talks. To this end, Palmerston proposed that Britain back Mohammed Khan’s rival, Shuja Shah Durrani, and restore him to the Afghan throne and thus make him forever obligated to the United Kingdom. As we now know, this not only proved to be disastrous but saw Palmerston sacked from the Foreign Office. Palmerston insisted that had he been allowed to remain, the defeat at Bala Hissar would never have happened and he blamed his successor for mismanaging what should have been (in Palmerston’s view) “a swift and easy victory”. That successor was none other than Lord Melbury, now Prime Minister.

In the interim, as we have seen, Britain’s interests in Afghanistan diminished as Russia’s interests increased. This was slightly offset by the acquisition of Hong Kong in terms of economics but where the Great Game was concerned, the United Kingdom now faced a situation in which Russia was becoming dominant in the region. This is why the Graham government had been so keen to apply pressure to the Russians in Vienna when they transgressed against the Straits Pact. Not doing so would give them a blank cheque to behave as they wished, not only in the Dardanelles but elsewhere. Now Britain looked on as Russia looked likely to take advantage of a cry for help in securing vast swathes of territory they had long coveted. Though the Foreign Office had discussed these developments for weeks, it was not until August 1845 that the situation was made public. In an urgent question in the Commons, Palmerston asked what response the government proposed to take if the Russians marched on Bukhara. When he was told that a response was being formulated but no comment could yet be given on what that response might be, Palmerston launched into a bitter tirade against his own front bench, declaring that every moment wasted was a further boost for Russian aggressions. He slammed the Tories for failing to “rebuke the Russian bear” in the Vienna talks in 1844 but he then turned on Lord Morpeth, saying that where the Tories had failed, the Foreign Secretary had simply given in by his own disinterest. This was hardly fair to Lord Morpeth but Palmerston’s intervention brought the issue to the fore with such force that a response could no longer wait. The Opposition, poised to take back the reigns of government at any opportunity, smelled blood. One wrong step where Afghanistan was concerned and Melbury’s government could fall and Sir James Graham might be returned to Downing Street.

At Buckingham Palace, the King and Queen were not really following this debate with any noticeable interest – if they were at all. Amongst their usual public engagements, both were distracted from the big conversation on foreign policy by their own pet projects – as well as adapting to married life. For the King, his great interest in the railways had returned with a passionate zeal when he gave Royal Assent to a vast number of railway acts, parliament having sanctioned the construction of nearly 3,000 miles of new track up and down the country [2]. This marked the beginning of ‘railway mania’ in which investors rushed to pour their money into railway shares for a quick return. Hundreds of companies were formed in the hope that they might make their fortune from the railways and nobody could be more excited by this than King George V. For His Majesty, the interest was not financial to begin with. He was drawn to the “railway mania craze” because he had long been fascinated by technological innovations in transport. He believed that the railways offered “the greatest opportunities to the people they have known for many a year” and that “everybody should look with excitement and interest in the way Britain is leading the pack on the rolling out of a new, modern railway network”. We do not know how George felt about the railways being used as a plaything for investors, neither do we know whether he approved of the way such projects were being funded at this time, but we do know that in August 1845, the King himself explored the possibility of investing some of his private fortune into a railway company.

By 1845, the King had noticed a significant drop in his bank balance. The redevelopment and construction at Regent’s Park and the acquisition of his new Scottish estates had not come cheap and now the King’s annual Civil List payment of £60,000 a year could no longer be frittered away on vanity projects with the reassurance of a healthy private sum to bail the Royal Family out of financial difficulty. Since his coronation, George had sought no increase to the Civil List but it looked likely that he would soon have to. Parliament voted the Queen an annuity of £48,000 a year shortly before her marriage but this was spent almost before it was received in ways we shall shortly explore further. Keen to boost his coffers once more, George V began to think seriously about investing in the railways, buoyed by the idea that he would be putting his money into something he understood and cared about. But when he discussed this matter with the Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Parker looked slightly confused. He told the King he would “consider if such an investment could be made by the Crown”, something George himself had taken for granted that it could. The fact was that whilst the Crown Estate did regularly invest in property and land, the arrangements made when the Civil List was first adopted in 1760 meant that any profits from the Crown Estate went to the nation and not the Sovereign personally. In other words, if the King invested and if he was successful, he could not keep the profits of his portfolio and could only expect a modest increase on his annuity granted by parliament. The rest would go to the Treasury.

John Parker did not seek to dissuade the King, indeed he saw no reason why if Members of Parliament could heavily invest in railway companies, George V could not do likewise. But this raised a controversial and long running debate regarding the monarch’s finances; how much of the King’s private fortune was really his and did the government have the right to advise him how and where that might be spent? When Cabinet discussed this question, their view was unanimous. It would be deeply inappropriate for the Crown Estate to be seen to gamble on the stock market with assets which were “held in trust for the nation”. But they could have no objection to the King investing his own money. To this end, the entire matter was put into the lap of the Earl of Chichester, then Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Whilst King George III handed over the proceeds of the Crown Estate to parliament in exchange for a regular annuity through the Civil List, he had a secondary source of independent income which remained his own. As Duke of Lancaster, George III held assets including but not limited to 45,000 acres of land holdings and various properties which brought him an annual income of around £90,000 – the equivalent of £9.2m today. [3]

This increased as the Duchy sought to buy more land and acquire more property (George V himself placed Hanover House and Birkhall under Duchy authority) until the income from this revenue stream in 1845 stood at around £150,000 a year – the 2023 equivalent of £15m. The Sovereign did not pay tax on this income, he was not at liberty to declare his interests or assets and the Duchy itself regularly invested the King’s money (through his bank at Coutts) in new assets. The Chancellor of the Duchy wrote to the Chancellor of the Exchequer formally advising him that the Duchy was to seek out investment opportunities in the railways. The Chancellor acknowledged this but suggested “that the King’s personal finances not be explored or discussed further in this manner”. In other words, the government saw no clash of interest but it did not want to see the purchase of any shares appear in the newspapers. The King’s enthusiasm revived, he now set about scouring records of new companies cropping up all over Britain to see which he might like to invest in. He also called in officials from the Duchy of Lancaster to discuss the plans these companies might have for rolling out new track in the lands the King called his own through his Lancaster portfolio. [4]

Queen Agnes meanwhile thought her husband’s preoccupation with “railway mania” was “really quite silly” and pondered to her ladies, “Why do men like such big noisy machines?”. Princess Mary was in agreement. She had been on a train once and hated it so much that she swore never to board another in her lifetime – “And I do not see how the poor will be served well by all this rushing about. It will unsettle them and make them very restless”. The King ignored these negative opinions and instead, studied his timetables. But the Queen had her own work to do, eager to throw herself back into her work after her brief sojourn at Birkhall. Whilst there she had listened to the advice of her husband and had tried to keep things in a balance, not overworking whilst remembering she had certain obligations to fulfil. That said, by August 1845 she had finally settled on an idea she wished to make a reality and which would perhaps become her defining legacy in Britain. Following on from her meetings with representatives from hospitals and nurses (not to mention Elizabeth Fry), the Queen wrote to the Home Secretary, Lord John Russell, asking if she might see him. It is likely that she had heard of Lord John’s reforming zeal and it stands as testament to her quick understanding that in seeking government advice for her plans, she turned to him rather than the Chancellor of the Exchequer or the President of the Board of Control.

What Agnes had in mind was really quite simple in theory; she wished to raise four new community hospitals in an underprivileged area which offered free medical care at the point of use. The government could have no objection to this for fashionable ladies often fundraised for such projects, indeed, this was the backbone of the British healthcare system in 1845. These four hospitals were to be known as the Royal Free Hospitals and would be funded by private investment and charitable works but what made them so different to similar establishments already operation in England and Wales was not so much the modernity of the buildings themselves but the new approach to how these hospitals would be run. It was the Queen’s intention to find a suitable property in the capital which she would buy and transform into a home for nurses, to be trained by Mrs Fry’s sisters from the Nursing Institute, but who would not work only for the privileged and wealthy patrons who could afford to hire them. Rather, these nurses would treat everybody, regardless of background, who sought assistance at the Royal Free Hospitals. They would be paid not by any one individual but by the Board of these new establishments and for the first time in England, these nurses would be put through a standardized period of training for which they would receive formal recognition of their expertise in the field of nursing. It was the Queen’s intention that the first intake should train the second, the second should train the third, and so on and so forth, until this template could be rolled out across the country giving rise to a whole new generation of Royal Free Hospitals.

“So what do you think of that Lord John?”, Agnes grinned excitably when she had finished explaining her ambitions to the Home Secretary, “I have written to Mrs Fry and asked for her help and I…”

“Yes…yes quite”, Lord John mused, somewhat shell-shocked, “And the King Ma’am? What does His Majesty think of this?”

“He knows the basics”, Agnes nodded seriously, “But I thought it better to talk to you first because I know in England that is how things are done”

Lord John scratched his head and smiled politely, “Yes Your Majesty…very wise…Ma’am…what you propose is truly a very sound and very welcome initiative. Indeed, I should give it my wholehearted support and so too I believe would the vast majority of politicians, not to mention those in the country as a whole who stand to benefit from this but…might I ask how this is to be afforded Ma’am? It all sounds horribly expensive”

“Well, I am in receipt of my annuity and…”, Agnes began, counting up the financial armoury on her fingers, “And May tells me that lots of people would help if they knew I had chosen this as a cause and…”

“Yes Ma’am but, with respect, parliament voted the annuity to assist with the expenses of your duties and your household”, Lord John explained patiently, “The monies cannot be spent on charitable causes as you describe…at least I don’t believe they could be…without some kind of explanation to the Commons. You see Ma’am, the argument would be that if you are not using the monies for the reimbursement of your expenses by virtue of your position as Queen consort, then there is little cause for the annuity to be given in the first place…”

The Queen fell silent and looked sheepishly at her shoes.

“I did not know that”, she said quietly, “I thought…I thought it I could give it to those who need it more than I”

Lord John smiled warmly.

Lord John Russell.

“A most admirable trait Ma’am”, he beamed, “And I cannot fault your motives, they are truly a credit to you, to His Majesty and to the country. But it is not that simple”

“Then my plans were all a waste of time”, the Queen sighed sadly.

“Not at all Your Majesty!”, Lord John grinned encouragingly, “I think they’re very fine plans, very fine indeed, and I am in agreement with the Duchess of Grafton that many would wish to help. Permit me a little time with this Ma’am and I am sure we can find a solution”

“Oh Lord John! Do you really think so?!”, Agnes bounced enthusiastically, “I should be so happy if you could help and I know I could make a success of this, I have made lists you see and May has helped me and we think that…”

Lord John nodded as the Queen began explaining the finer points of her proposals at record speed. Yet he did not patronise her and when he returned home that evening, he remarked to his wife Frances; “I truly believe our eager little Queen has confessed herself a Whig”.

Meanwhile at Buckingham Palace, the “eager little Queen” was dressing for dinner when the King appeared in the salon which connected their bedrooms.

“Nessa darling…”, the King called through the door, “I am just here to tell you we have twenty minutes before our guests arrive…”

George was quickly learning that punctuality was not one of the Queen’s strongest suits but to his delight, she appeared almost immediately in a beautiful gown of turquoise silk with white paper apple blossoms woven into her hair.

“You look charming my dear”, George smiled as his took her hands and kissed Agnes’ cheek, “Most charming indeed. How did you get on with Lord John today? He wasn’t too frightening I hope?”

“Not at all!”, Agnes beamed, “I thought he was very kind and very helpful”

“Good”, the King nodded approvingly, “But I think we had best not mention your little scheme at dinner, what? Best to keep it light, keep it gay. I understand our Prime Minister is a tad overwrought and we don’t want to overwhelm him now, do we?”

Agnes nodded seriously as if the King had announced the Prime Minister was in the throes of a serious illness.

“Oh no, we mustn’t do that Georgie”, she said gravely, “He’s such a dear man. I shan’t mention my little talk with Lord John, I promise. Why is the Prime Minister so…over-ought?”

The King chuckled; “Over-wrought”, he said, emphasising the ‘r’ sound to help the Queen, “Worried, that is, he’s a little weighed down with things. That’s really why I wanted to speak with you before everybody gets here. Nessa, do stop fussing with your hair…”

“Sorry dear”, Agnes smiled, theatrically sitting on her hands as proof that she was concentrating.

“Phipps tells me that it’s highly likely we shall be asked to go abroad for a time…that Foxy may well ask me for my agreement tonight…it’s been a suggestion until now but I believe Charlie is right when he says the PM may wish to make it more than a suggestion and commit us to a decision one way or another”

“Abroad?”, the Queen inquired curiously, “Where to?”

The King lit a cigarette, ignoring his wife's dramatic flapping of her hands to clear the smoke cloud, and cleared his throat.

“To Russia. To see my sister…”

Notes

[1] What we have in these opening paragraphs is a blend of the OTL history and the consequences of the PoDs and thread pulling we did in Parts Two and Three. I’ve included some OTL ballast to make the forthcoming changes to what actually happened more plausible but really this is building on the changes I introduced from 1838 – 1842 ITTL to give us a different outcome.

[2] As in the OTL.

[3] We know that Prince Albert “advised” his wife to make investments with her Duchy income, though we’ve never found out what these investments actually were.

[4] This may seem irrelevant but it does open up the possibility that the King may become very rich (or lose a packet) on his investments which I think could lead to some interesting developments in this arena.

And so we begin to move into foreign affairs which will dominate this Part of our story but I've tried to mix in some domestic themes too - I hope the balance will work out and prove engaging!

I'm honestly very touched and very grateful, thankyou!Of course it deserves the nom! 😄 The level of detail, the quality of the characters and the speed with which you manage to put out the chapters more than makes it worthy of a turtledove!

That's so kind of you @nathanael1234, you've always been such a great supporter of TTL and I really do appreciate it.I’m glad I got the chance to second the nomination for this timeline. This is my favorite timeline on this site and I think it deserves all the praise it has been getting.

Thankyou so much! I'm always amazed that people are still happy to read on and it's a pleasure to keep Crown Imperial going along as the ITTL years pass. My sincere thanks again.I too am happy to have nominated you, because your story is the first one that grabs me and manages to always keep my expectations and curiosity in each of your updates. in a nutshell I liked the other stories I read but then they diminished for me while this is the exact opposite I didn't think that a story about yet another English or British monarchy fascinates me so much plus your extras about other countries they are fantastic and always well prepared.

Thankyou!We will see George's sister and her family!

We'll soon be heading to Russia to spend a little time with Lottie which will include some background on what her life has been like since her marriage.

As any trip like this often meant stopovers to visit other relatives too, we'll also be catching up with Victoria so we can bring things up to date with both.

This chapter was pretty good!

I’m glad that Agnes wants to help as many people as possible. But, she might get a bit over her head

Also, Palmerston returns. I guess he is too big a figure to just fade away.

One more thing, what happened to William Mansfield? He was George’s friend at Sandhurst and he just faded into the background.

I’m glad that Agnes wants to help as many people as possible. But, she might get a bit over her head

Also, Palmerston returns. I guess he is too big a figure to just fade away.

One more thing, what happened to William Mansfield? He was George’s friend at Sandhurst and he just faded into the background.

Thankyou so much!This chapter was pretty good!

I’m glad that Agnes wants to help as many people as possible. But, she might get a bit over her head

Also, Palmerston returns. I guess he is too big a figure to just fade away.

One more thing, what happened to William Mansfield? He was George’s friend at Sandhurst and he just faded into the background.

As to William Mansfield, at this stage in our timeline he's pretty much still a junior courtier, he wouldn't be "in the presence" each day but he'd likely make up the numbers for dinner or a shooting weekend. Friendships wax and wane so he's fallen a little off the radar but 1845 is quite an important year for him as in late 1845, he asked to be transferred to an Indian regiment. So we'll certainly visit him again briefly before we get to the Anglo-Sikh War in December.

How many children has Princess Charlotte had?

Is it the same as Marie of Hesse IOTL?

Is it the same as Marie of Hesse IOTL?

So far she's had two; Grand Duchess Alexandra Alexandrovna (b. 1842) and Grand Duke Nicholas Alexandrovich (b. 1844).How many children has Princess Charlotte had?

Is it the same as Marie of Hesse IOTL?

Can confirm there are more on the way - though perhaps not quite so many as Marie of Hesse in the OTL.

A little bit of an update to accommodate some personal news.

I'm afraid the next chapter of Crown Imperial will be delayed until the end of next week. My plan is to get back to twice weekly updates from there, so thank you for your patience! But the reason I'm facing a bit of a delay with this project is because, happily, I've got a new one...

I can't really say too much about it but I'm thrilled to tell you guys that I've just secured a publisher for a new title. I can probably confirm that it's non-fiction, very much in my sphere of interest and I have a deadline of around 18 months. But as soon as I can share more detail with you, I will.

Once again, a huge thankyou for your support and interest in the timeline. It's not going anywhere but as I say, there'll be a brief delay to us getting back on track as I start putting in the basics for this new work. It's an exciting time and I'm delighted to have this new project but I love working on Crown Imperial and for as long as you guys enjoy reading it, I'll keep writing it!

I'm afraid the next chapter of Crown Imperial will be delayed until the end of next week. My plan is to get back to twice weekly updates from there, so thank you for your patience! But the reason I'm facing a bit of a delay with this project is because, happily, I've got a new one...

I can't really say too much about it but I'm thrilled to tell you guys that I've just secured a publisher for a new title. I can probably confirm that it's non-fiction, very much in my sphere of interest and I have a deadline of around 18 months. But as soon as I can share more detail with you, I will.

Once again, a huge thankyou for your support and interest in the timeline. It's not going anywhere but as I say, there'll be a brief delay to us getting back on track as I start putting in the basics for this new work. It's an exciting time and I'm delighted to have this new project but I love working on Crown Imperial and for as long as you guys enjoy reading it, I'll keep writing it!

Last edited:

Thankyou! Once my new schedule settles a little it'll be easier to have certain days for new updates here so hopefully the disruption should only be minor.Congratulations on your new project! Wish you all the ebst and good luck!

And we understand, take all the time you need!

Congratulations on your publication contract! I love Crown Imperial and as long as you keep writing I'll keep reading!

(I was also going to say that I'm looking forward to the update on Victoria and Charlotte and think you've made a great choice in working that into the political narrative.)

(I was also going to say that I'm looking forward to the update on Victoria and Charlotte and think you've made a great choice in working that into the political narrative.)

First of all congratulations for your achievement I wish you good luck, but Georgie intends to give birth to a new variant of the Grand Tour : Russian passion edition , we will see the future tsarina teaching her brother the polka, or she will decide to volunteer for the construction of the Trans-Siberian,

he will receive the Cossack or Hussar uniform as a gift (I see this option as the most likely of my nonsense in this comment),

knowing his love for animals he asks Nicholas I as a pet for a polar bear ( you just need to figure out where to put it uhm... )

I can already imagine him trying to win the contest on who is better between him and Sasha with his grandchildren ......

Ahahah , ok getting serious for a moment, our viceroy maybe he will intend to accept the role of Admiral of the German Confederation offered to Hanover at the Congress of Vienna?

he will receive the Cossack or Hussar uniform as a gift (I see this option as the most likely of my nonsense in this comment),

knowing his love for animals he asks Nicholas I as a pet for a polar bear ( you just need to figure out where to put it uhm... )

I can already imagine him trying to win the contest on who is better between him and Sasha with his grandchildren ......

Ahahah , ok getting serious for a moment, our viceroy maybe he will intend to accept the role of Admiral of the German Confederation offered to Hanover at the Congress of Vienna?

Last edited:

Thankyou all so much for your very generous congratulations on my recent good news! I'm very grateful for your support. And I should also add a huge thankyou to anyone who has very kindly cast their vote in the Turtledoves for TTL. It really is very much appreciated.

I'm just formatting two chapters now, the first of which prepares us to go to Russia and the second of which is the much-requested update on Lottie.

This usually takes about 30/40 minutes so it will be with you soon and though I don't usually like to double post as I know some people miss the first new instalment and only see the second, we haven't had an update for a fortnight and I'd like to return to our normal posting schedule with these two together as a thankyou for your patience.

So, St Petersburg...here we come...

I'm just formatting two chapters now, the first of which prepares us to go to Russia and the second of which is the much-requested update on Lottie.

This usually takes about 30/40 minutes so it will be with you soon and though I don't usually like to double post as I know some people miss the first new instalment and only see the second, we haven't had an update for a fortnight and I'd like to return to our normal posting schedule with these two together as a thankyou for your patience.

So, St Petersburg...here we come...

Threadmarks

View all 131 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

GV: Part Four, Chapter Five: Looking Away GV: Part Four, Chapter Six: Brothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Seven: Mothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Eight: An Answer to Prayer GV: Part Four, Chapter Nine: Kings and Successions GV: Part Four, Chapter Ten: Cat and Mouse GV: Part Four: Chapter Eleven: Secrets and Lies GV: Part Four, Chapter Twelve: Life at Lisson

Share: