Archibald

Banned

Goodbye Spacehab !

The next day, February 4, 2003 – Columbia Flight Day 20 – Anderson and Brown did a seven hour sortie outside that remained in the history books.

Once again they pushed boundaries – of their bodies, of what the shuttle and its payload could endure.

That day, Mike Anderson and David Brown thrown Spacehab out of the Columbia orbiter !

(music: The Jacksons, Can you feel it)

They crawled to the bottom of the payload bay and retrieved torque multiplier tools. With them they opened the big latches that fixed the habitat to the orbiter that carried it into orbit.

They had a brief thought for all the NASA and Spacehab workers that had care-taken the module on a warm day in Florida - only a month before, in a past now so far away !

They grabbed cutters and started butchering a host of electrical and water lines from which Columbia had fed and nourished the module it carried. They felt like David Bowman butchering HAL brain on the way to Jupiter, although fortunately Spacehab did not talked to them.

Then the time come to cut the umbilical cord – the tunnel adapter that ran from Columbia airlock to the module. There was a flexible joint there made of kevlar, cloth and wiring, and cutting that mess was not easy.

Even then, however, Spacehab refused to left Columbia for a simple reason: it did not had little rocket thrusters to pull himself away. It would be Columbia, under control of commander Rick Husband, that would literally back away, then flee out of the module reach.

Yet the module was so balky that Anderson and Brown had to help it outside, much like a pair of nurses helping a pregnant woman to give birth. Centimetre by centimetre the two astronauts pushed the cumbersome module out of the payload bay. The process however took so much time and they were so exhausted with their reserves dwindling down that in the end the astronauts literally kicked the module with their boots.

It was an eerie sight: a pair of astronauts strapped inside a shuttle payload bay and furiously kicking the ass of a 18 000 pound module !

After minutes of exhausting efforts Spacehab at least crossed the threshold of Columbia payload bay doors. With Anderson and Brown solidly tethered to the orbiter, commander Husband manoeuvred his crippled orbiter away from the abandoned Spacehab.

The rest of the crew gathered around the cockpit windows to watch, incredulously, Spacehab drifting away. Much like the dead Frank Poole becoming the first man to Saturn, Spacehab première would be a pyrrhic victory; soon the atmosphere would take his toll and it would tumble and burn - like Russian space station Mir two years before.

Auf wiedersehen Spacehab !

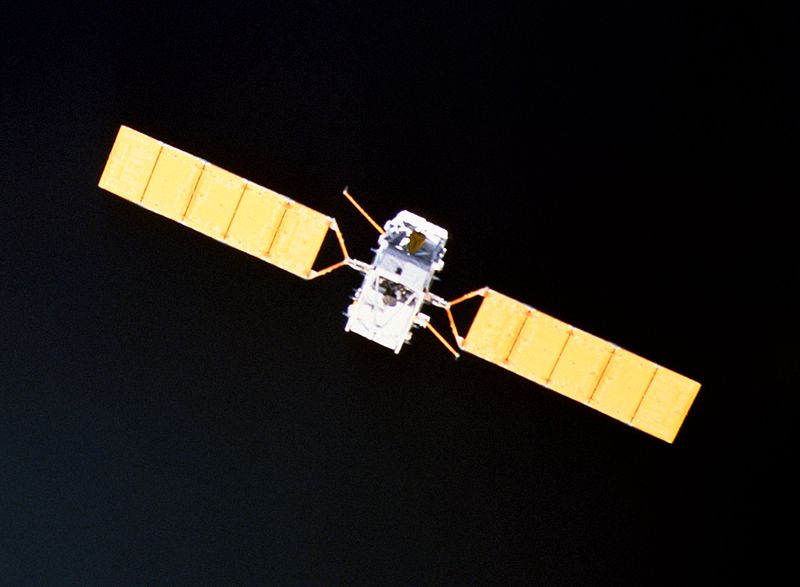

(this is a picture I fabricated myself - I found a picture of Spacehab in the shuttle payload bay, then I literally "erased" the shuttle bay behind Spacehab using MS Paint. Tedious job !)

At that very moment, and in a stunning revenge against NASA (and the shuttle) tortured history, Spacehab had become a space station on his own.

The next day, February 5, 2003 – Columbia Flight Day 21 – Anderson and Brown did another seven hour sortie outside. This time they got ride of the 4400 pound heavy Freestar, the big truss where Get Away Specials and Hitchhickers were bolted. It was an easier task than throwing Spacehab overboard.

Once again they had a brief thought for all the labs and universities students and researchers that had spent so much money, time and energy refining all the experiments now drifting away from Columbia to a certain destruction within Earth atmosphere.

Meanwhile down on Columbia flight deck, Kalpana Chawla frantically snapped photos of the abandoned Freestar.

The day before it had been Ilan Ramon that had taken pictures of the drifting Spacehab. Never, never in my life will I see something like this, she thought.

The next day, February 4, 2003 – Columbia Flight Day 20 – Anderson and Brown did a seven hour sortie outside that remained in the history books.

Once again they pushed boundaries – of their bodies, of what the shuttle and its payload could endure.

That day, Mike Anderson and David Brown thrown Spacehab out of the Columbia orbiter !

(music: The Jacksons, Can you feel it)

They crawled to the bottom of the payload bay and retrieved torque multiplier tools. With them they opened the big latches that fixed the habitat to the orbiter that carried it into orbit.

They had a brief thought for all the NASA and Spacehab workers that had care-taken the module on a warm day in Florida - only a month before, in a past now so far away !

They grabbed cutters and started butchering a host of electrical and water lines from which Columbia had fed and nourished the module it carried. They felt like David Bowman butchering HAL brain on the way to Jupiter, although fortunately Spacehab did not talked to them.

Then the time come to cut the umbilical cord – the tunnel adapter that ran from Columbia airlock to the module. There was a flexible joint there made of kevlar, cloth and wiring, and cutting that mess was not easy.

Even then, however, Spacehab refused to left Columbia for a simple reason: it did not had little rocket thrusters to pull himself away. It would be Columbia, under control of commander Rick Husband, that would literally back away, then flee out of the module reach.

Yet the module was so balky that Anderson and Brown had to help it outside, much like a pair of nurses helping a pregnant woman to give birth. Centimetre by centimetre the two astronauts pushed the cumbersome module out of the payload bay. The process however took so much time and they were so exhausted with their reserves dwindling down that in the end the astronauts literally kicked the module with their boots.

It was an eerie sight: a pair of astronauts strapped inside a shuttle payload bay and furiously kicking the ass of a 18 000 pound module !

After minutes of exhausting efforts Spacehab at least crossed the threshold of Columbia payload bay doors. With Anderson and Brown solidly tethered to the orbiter, commander Husband manoeuvred his crippled orbiter away from the abandoned Spacehab.

The rest of the crew gathered around the cockpit windows to watch, incredulously, Spacehab drifting away. Much like the dead Frank Poole becoming the first man to Saturn, Spacehab première would be a pyrrhic victory; soon the atmosphere would take his toll and it would tumble and burn - like Russian space station Mir two years before.

Auf wiedersehen Spacehab !

(this is a picture I fabricated myself - I found a picture of Spacehab in the shuttle payload bay, then I literally "erased" the shuttle bay behind Spacehab using MS Paint. Tedious job !)

At that very moment, and in a stunning revenge against NASA (and the shuttle) tortured history, Spacehab had become a space station on his own.

The next day, February 5, 2003 – Columbia Flight Day 21 – Anderson and Brown did another seven hour sortie outside. This time they got ride of the 4400 pound heavy Freestar, the big truss where Get Away Specials and Hitchhickers were bolted. It was an easier task than throwing Spacehab overboard.

Once again they had a brief thought for all the labs and universities students and researchers that had spent so much money, time and energy refining all the experiments now drifting away from Columbia to a certain destruction within Earth atmosphere.

Meanwhile down on Columbia flight deck, Kalpana Chawla frantically snapped photos of the abandoned Freestar.

The day before it had been Ilan Ramon that had taken pictures of the drifting Spacehab. Never, never in my life will I see something like this, she thought.