What a name.. Ofcourse not the British oneI guess!Winston Churchill (L) (1909)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Cinco de Mayo

- Thread starter KingSweden24

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Since you switched Teddy and Hearst, did Roosevelt become a one term congressman like hearst?

It's over. The socialist party had hell of a run, but shame to see it lose and go to irrelevancy.Democrats defeated the Socialist turncoat Richard Pettigrew

Well, Churchill's mother was American, so it's possible.What a name.. Ofcourse not the British oneI guess!

Nope! Was an American adventurer/writer from NH (fellow Granite Stater John Hay was a big fan of his books and often had him out to the Fells) who eventually dabbled a bit in politics as a progressive Republican in the Teddy Roosevelt years but never got past the primary. Couldn’t resist using somebody with a name like thatWhat a name.. Ofcourse not the British oneI guess!

No, but he was (for a while) Mayor of New York, and managed to piss off Hearst, Sulzer, the whole gangSince you switched Teddy and Hearst, did Roosevelt become a one term congressman like hearst?

Well, don’t speak too soon. It’s going to be a very big deal in municipal politics even if it has a very hard ceiling in national politicsIt's over. The socialist party had hell of a run, but shame to see it lose and go to irrelevancy.

Nice to see John Burke of Dakota making his apperance in Dakota - he was, in OTL, a pretty damned good Governor and honorable dude (had to be to get elected as a Dem in OTL North Dakota!). I'm looking forward to seeing some of the OTL NPLers poke their heads onto the state and national scene; though, as we've discussed, most will certainly be Socialists in the ATL. This TL will certainly be ... livened up even more by future president Wild Bill Langer  (and no, I don't expect him to actually be President- though THAT would be a timeline like no othe!)

(and no, I don't expect him to actually be President- though THAT would be a timeline like no othe!)

On a sidenote, my sleep addled Upper Midwestern brain kept reading FL as "Farm Labor" rather than "Fusion Liberal" and got a bit confused for a while!

On a sidenote, my sleep addled Upper Midwestern brain kept reading FL as "Farm Labor" rather than "Fusion Liberal" and got a bit confused for a while!

Last edited:

1914 Midterms Update

"...made it clear that he opposed the "electoral truce," or at least that Clark and Mann were encouraging it; Norris was not necessarily against it, but was skeptical whether it would be abided and took the dominant results Democrats enjoyed in many states suggested to him that Clark could have won an outright majority for his Speakership had so many state parties not "stood down." Much like his fierce advocacy for worker's compensation, his time would have to wait, but Norris among all others was certainly curious to see what would come of this "hung Congress."

The reality was that not much would change; the thin majority for Clark, and the narrow minority for Mann, meant that both men were returned by their respective caucuses despite some grumbling among the Butlerites on the Liberal side of the aisle, greased along by Mann strategically promising moderate fence-sitters and a handful of amenable Butlerites juicy committee postings after the turnover that had seen as much as a third of the Liberal caucus leave via retirement due to various impacts of the war. The Democratic attrition was milder, and that suited Norris well - he could earn his cachet with the more determined new members and had his reputation intact with the returnees. This knife's-edge Congress meant that one of the two men who effectively served as "co-Speakers" would continue to do so atop the War Committee, and it became relatively clear that it would be Clark - there was, quite simply, no mathematical path for Mann to become Speaker, but Clark did need every vote nonetheless to officially clear the bar that was required by the Constitution.

Enter Victor Berger, the Austrian-born chief Socialist in the House who had just watched half of his miniscule caucus melt away but quite critically still had enough votes to put Clark over the top even if some of his caucus chose to abstain or vote against Clark on the floor. The most critical divide within the American Socialist cause in 1914 was related to its reformist or its revolutionary strains, and to what extent the radical International Workers of the World labor union conglomerate would dictate the Socialist Party's behavior. The election had seemed to answer that question rather definitively - not particularly much. The most hard-left elements of the IWW were largely associated with the Western Federation of Miners, which had frequently clashed with state and governmental authorities in the "mine wars" that had plagued the West for over a decade, and the WFM had just watched a number of its key figures - Charlie Moyer of Colorado and Vincent St. John of Nevada in particular, both being crucial WFM organizers and former Presidents - be turfed out of the House as populist Democrats ran hard in mining and logging districts with transient populations disrupted by the war. One of the survivors, Representative Ed Boyce of Idaho, was himself a former President of the WFM, who had gradually become disillusioned with the practicability of the IWW's revolutionary impulses but had nonetheless remained committed to socialism as an economic philosophy and, via the destruction of his party's caucus in the midterms when the "punch to the left" of the Democrats, now was one of the party's key figures.

All Clark needed, then, were Berger and Boyce provided that no Democrats voted against him or abstained, and Norris was surprised when he was asked to be part of the whip operation to sustain that crucial measure in the months and then weeks ahead of the swearing in of a new Congress, in that role supporting incoming Majority Whip John J. Fitzgerald of New York, a brash but smooth-talking Irish-American who had been chummy with Sulzer and the Tammany Hall machine of his native city alike, and from then on the political fates of "J.J. Fitz" and Norris were intertwined, barreling towards their perch atop the House alongside each other in the 1920s. The decision by Fitz to include Norris in Clark's internal whip operation was partially strategic and partially familiar; the men got on well and Norris regarded the younger but more tenured and senior man to be an unusually honest politician considering that he had emerged out of the viper's den of New York City politics, while Fitz in turn thought of "Honest George" as a man who both he and the Prairie Populists who couldn't see the forest for the trees could trust, and thus Norris was now the liaison between the most progressive agrarian rebels and Clark, a position that gave him a foot in both camps and instantly marked him as a man of tremendous influence at the hingepoint of the Democratic House coalition.

As for Berger, the "Red Kaiser of Milwaukee" understood perfectly well how the game was played. While three of his Socialists were uncommitted (or unpersuaded), Berger promised Clark and Fitz the votes of himself, Boyce and freshman Meyer London of New York (who most certainly needed good relations with Tammany Hall to have any hope of future reelection) in return for the Democrats granting him a position on the powerful Rules Committee and Boyce a seat at the table on the Special Committee on the War - which, in effect, meant that the chair of the Congressional Socialists now had a role in setting the conduct of the whole House, and his lieutenant was the formal tiebreaker whose membership on the War Committee made it a body now with an uneven number of members. While no fan of backroom deals early in his career, Norris came away impressed, and the though the episode as a whole left a bad taste in his mouth for the naked politicking of it, it nonetheless made an impression on him on how "good men can work together in creative ways."

In the end, thanks to Norris' months between the election and the Speaker vote working his colleagues, only three firebrand Democrats, all Kansans and Nebraskans, declined to vote for Clark, but they agreed to abstain from the ballot rather than vote no on the floor - all the other potential rebels voted in favor, and the three holdout Socialsits themselves abstained. This had the effect of considerably lowering the threshold needed to become Speaker, but Clark and Fitz kept their bargain with Berger in the entirety of the 64th Congress. The first, and certainly not last, informal coalition agreement in the United States House had been struck, and Norris had been integral to its formation, which Clark would not soon forget. The Missourian began to rethink his earlier skepticism of Norris and saw him in a new light, as something more than just a Bryanite rabble-rouser from Nebraska.

The ascent to the top of the pyramid, which few could have suspected considering his previous history, had begun in the shadow of certainly one of the strangest and most unique elections in the history of Congress..."

- The Gentle Knight: The Life and Ideals of George W. Norris

"...Hughes, if candid, would admit he didn't particularly care for either of the Senate leaders, finding Penrose sleazy and Kern patronizing, much preferring the moderate chumminess of the Clark-Mann duopoly in the House. "It is perhaps the first time in the history of this Republic," he wrote in amusement to an old law partner, "that the House is the body where comradery rules the day!" To Hughes, the against-the-grain Senate results were of little comfort, nor was the relatively threadbare margin that Clark had eked into the Speaker's chair with. The results in the states were, put simply, disastrous. All the work done at the dawn of the decade by men such as himself and his comrades in New York, or James Garfield in Ohio, or Frank McGovern and Robert LaFollette in Wisconsin, seemed to have been for naught. The brief hour of progressive Liberal ascendance in state parties and state houses looked to be over just four short years after it started and it began to get Hughes wondering if that might foretell problems for his own Presidency.

This was not to say that he was, or thought of himself as, unpopular. Supportive letters arrived by the bucketloads every day, and when greeting troops he was met with friendly astonishment. But the heaviness of the project at hand, and the sense that his efforts to center the Liberal Party at the heart of the American political and philosophical spectrum rather than trying to dig in its heels against the steady tide that was washing away the triumphs of Blainism [1] was perhaps not imbued with the certainty and permanency that he had once hoped. Despite the encouragement of Root, and the knowledge that he would see some changes in his Cabinet come January, Hughes took the shellacking at the state level as a partial indictment of himself, and the heaviness which he carried only worsened..."

- American Charlemagne: The Trials and Triumphs of Charles Evans Hughes

"...both Berger and Boyce were foreign-born, probably no coincidence in their deep connection to immigrant communities in their home districts [2], and thus had a more worldly sense of perspective on the setbacks and the advances that the Socialists were making. It became immediately clear to them that the "Haywood Headache" in the West was a major problem; Bill Haywood's imperious attitude within the WFM, his scornful attitude towards participation in the electoral process, and the thuggish behavior of many of his miners at a time when the labor movement was shifting in a more conservative direction even outside of the establishmentarian AFL had served to alienate him from some of his supporters and made his name toxic to members of the public, especially out West where he was a mainstay of some notoriety in public life. With Debs' focus having turned exclusively to the advantages the ARU could wring from the nationalization of the railroad and the genuine opportunity to effect an industrial union [3] the result was that Berger especially became the centrifugal force of not just the electoral arm of American socialism but increasingly the movement itself (Moyer's decision to leave politics to focus on labor organizing exclusively helped Boyce become the chief figure of the Socialist Party in the West, at that), and Berger looked to the states for inspiration.

It was at the municipal level that the Socialists were seeing their greatest success, and 1914 may have underlined that story more than any other time as they shifted away from their base in the mining districts of the West. In New York, three prominent candidates had sought Congressional office - former Representative Morris Hillquit and newcomers Meyer London and Fiorello LaGuardia - with London triumphing and Hillquit and LaGuardia falling just shy of defeating incumbent Democratic Congressmen. This suggested to Berger that over a decade since the United Labor Party had collapsed along with the death of its once-champion Henry George [3], the ground was perhaps ripe for Socialism in the biggest city in America, and began pondering who might carry the torch for the party in 1917.

The Northwest was where the real action lay, though. Late 1913 and 1914 had seen three Socialists - former Democrat Harry Lane and longtime Socialists Hulet Wells and David Coates - elected as mayors of Portland, Seattle and Spokane, respectively; together, these were the three biggest cities in the Northwest and all three hotbeds of political radicalism. The Northwest was a strange place, a funhouse mirror microcosm of politics elsewhere. The Democrats dominated rural districts and the machines based out of cities, but had increasingly come under fire for corruption, the operation of gambling dens and illicit saloons, and organizing thugs to attack labor organizers or other disfavored groups, particularly in Seattle, where the vehemently anti-Socialist newspaper publisher Alden Blethen used his Seattle Times to gin up mobs and provoke violence. With the hostile terrain of much of the Inland Northwest in the times before the dam projects undertaken in the 1920s and early 1930s provided mass irrigation, though, Democrats were dependent on city voters, voters now increasingly frustrated with their public officials. Socialists could take advantage of that in the cities, but only to a point.

In Oregon and Washington, at the time though, there was a novelty known as fusion voting, in which parties could cross-endorse and run a single candidate on two lines, and the curious alliance of Socialists, pro-Prohibition "dry" Democrats, and Liberals could unite together against the urban and rural machines that controlled the states. In Seattle proper, this had some staying power as the Municipal League, which powered Wells' lengthy mayoralties, but elsewhere it was a curiosity that only occurred briefly in the early-to-mid 1910s. Socialists were too controversial to win statewide in either Washington or Oregon still, and Liberals too nonexistent outside of the cities to make much headway, but together - and by peeling off enough progressive Democratic voters, for actual Democratic politicians never went near fusionism out of fear of angering the machine - they could carry the day, and so they did behind the "Fusion Tickets" of Walter Lafferty and Ole Hanson, who were elected to the Senate in 1914 on the backs of one of the most unique coalitions to ever emerge in American politics. Socialists got their left-wing economic policy, Liberals and Dries got their good government reformism and hostility to the evils of drinking, gambling and whoring - everybody had something to gain by partnering together, different as they all may have been in background and views on capitalism.

It was thus that Berger, who got on well with Lafferty and Hanson but did not precisely endorse fusionism, ingratiated himself with Democratic leadership in the House while much of the party's base in the Northwest was now voting for very left-wing Liberals who were somehow in the same party caucus as men like Boies Penrose and Henry Cabot Lodge. The strange early adolescence of the Socialist Party's role as Congressional kingmaker had arrived..." [5]

- The American Socialists

[1] As covered, Blaine - for better or worse - serves to most Liberals of Hughes' generation and even more so for those older essentially the role Abraham Lincoln did for the Republican Party of OTL from 1860-1910ish. The conservative flank of the Liberals are, really, those men who just simply can't quit the good old Blaine-Hay paradigm they grew up with or came up in the party ranks during, and parties are rarely successful looking backwards rather than forwards. This, here, is how the Liberal dynasty that began in 1880 collapses upon itself entirely, though I'd argue the 1902/04 wipeouts were the real turning point - YMMV!

[2] In case it hasn't been made clear already, Ed Boyce represents Idaho mining country - aka the Panhandle, aka the National Redoubt and playland of America's white nationalist militia movement today (and, incidentally, where my girlfriend grew up). If you don't appreciate the irony of one of the chief Socialists representing Militialand USA, then do you even Cinco de Mayo?

[3] More on this, the effective germination of sectoral bargaining in the USA, in 1915

[4] Remember - he was the Mayor of New York in the mid-1880s back when the KoL was a thing

[5] Toldya it was getting weird. There really were some bizarre ad hoc coalitions of convenience in states where one party was dominant during the Progressive Era, though idk if any of them were quite as weird as "literal socialists and literal laissez-faire bourgeoise managerial types allying against machine bosses"

(Author's Note - one more midterm update coming, an Al Smith specific one, just wanted that in its own post so I can reference the threadmark title in the future.)

The reality was that not much would change; the thin majority for Clark, and the narrow minority for Mann, meant that both men were returned by their respective caucuses despite some grumbling among the Butlerites on the Liberal side of the aisle, greased along by Mann strategically promising moderate fence-sitters and a handful of amenable Butlerites juicy committee postings after the turnover that had seen as much as a third of the Liberal caucus leave via retirement due to various impacts of the war. The Democratic attrition was milder, and that suited Norris well - he could earn his cachet with the more determined new members and had his reputation intact with the returnees. This knife's-edge Congress meant that one of the two men who effectively served as "co-Speakers" would continue to do so atop the War Committee, and it became relatively clear that it would be Clark - there was, quite simply, no mathematical path for Mann to become Speaker, but Clark did need every vote nonetheless to officially clear the bar that was required by the Constitution.

Enter Victor Berger, the Austrian-born chief Socialist in the House who had just watched half of his miniscule caucus melt away but quite critically still had enough votes to put Clark over the top even if some of his caucus chose to abstain or vote against Clark on the floor. The most critical divide within the American Socialist cause in 1914 was related to its reformist or its revolutionary strains, and to what extent the radical International Workers of the World labor union conglomerate would dictate the Socialist Party's behavior. The election had seemed to answer that question rather definitively - not particularly much. The most hard-left elements of the IWW were largely associated with the Western Federation of Miners, which had frequently clashed with state and governmental authorities in the "mine wars" that had plagued the West for over a decade, and the WFM had just watched a number of its key figures - Charlie Moyer of Colorado and Vincent St. John of Nevada in particular, both being crucial WFM organizers and former Presidents - be turfed out of the House as populist Democrats ran hard in mining and logging districts with transient populations disrupted by the war. One of the survivors, Representative Ed Boyce of Idaho, was himself a former President of the WFM, who had gradually become disillusioned with the practicability of the IWW's revolutionary impulses but had nonetheless remained committed to socialism as an economic philosophy and, via the destruction of his party's caucus in the midterms when the "punch to the left" of the Democrats, now was one of the party's key figures.

All Clark needed, then, were Berger and Boyce provided that no Democrats voted against him or abstained, and Norris was surprised when he was asked to be part of the whip operation to sustain that crucial measure in the months and then weeks ahead of the swearing in of a new Congress, in that role supporting incoming Majority Whip John J. Fitzgerald of New York, a brash but smooth-talking Irish-American who had been chummy with Sulzer and the Tammany Hall machine of his native city alike, and from then on the political fates of "J.J. Fitz" and Norris were intertwined, barreling towards their perch atop the House alongside each other in the 1920s. The decision by Fitz to include Norris in Clark's internal whip operation was partially strategic and partially familiar; the men got on well and Norris regarded the younger but more tenured and senior man to be an unusually honest politician considering that he had emerged out of the viper's den of New York City politics, while Fitz in turn thought of "Honest George" as a man who both he and the Prairie Populists who couldn't see the forest for the trees could trust, and thus Norris was now the liaison between the most progressive agrarian rebels and Clark, a position that gave him a foot in both camps and instantly marked him as a man of tremendous influence at the hingepoint of the Democratic House coalition.

As for Berger, the "Red Kaiser of Milwaukee" understood perfectly well how the game was played. While three of his Socialists were uncommitted (or unpersuaded), Berger promised Clark and Fitz the votes of himself, Boyce and freshman Meyer London of New York (who most certainly needed good relations with Tammany Hall to have any hope of future reelection) in return for the Democrats granting him a position on the powerful Rules Committee and Boyce a seat at the table on the Special Committee on the War - which, in effect, meant that the chair of the Congressional Socialists now had a role in setting the conduct of the whole House, and his lieutenant was the formal tiebreaker whose membership on the War Committee made it a body now with an uneven number of members. While no fan of backroom deals early in his career, Norris came away impressed, and the though the episode as a whole left a bad taste in his mouth for the naked politicking of it, it nonetheless made an impression on him on how "good men can work together in creative ways."

In the end, thanks to Norris' months between the election and the Speaker vote working his colleagues, only three firebrand Democrats, all Kansans and Nebraskans, declined to vote for Clark, but they agreed to abstain from the ballot rather than vote no on the floor - all the other potential rebels voted in favor, and the three holdout Socialsits themselves abstained. This had the effect of considerably lowering the threshold needed to become Speaker, but Clark and Fitz kept their bargain with Berger in the entirety of the 64th Congress. The first, and certainly not last, informal coalition agreement in the United States House had been struck, and Norris had been integral to its formation, which Clark would not soon forget. The Missourian began to rethink his earlier skepticism of Norris and saw him in a new light, as something more than just a Bryanite rabble-rouser from Nebraska.

The ascent to the top of the pyramid, which few could have suspected considering his previous history, had begun in the shadow of certainly one of the strangest and most unique elections in the history of Congress..."

- The Gentle Knight: The Life and Ideals of George W. Norris

"...Hughes, if candid, would admit he didn't particularly care for either of the Senate leaders, finding Penrose sleazy and Kern patronizing, much preferring the moderate chumminess of the Clark-Mann duopoly in the House. "It is perhaps the first time in the history of this Republic," he wrote in amusement to an old law partner, "that the House is the body where comradery rules the day!" To Hughes, the against-the-grain Senate results were of little comfort, nor was the relatively threadbare margin that Clark had eked into the Speaker's chair with. The results in the states were, put simply, disastrous. All the work done at the dawn of the decade by men such as himself and his comrades in New York, or James Garfield in Ohio, or Frank McGovern and Robert LaFollette in Wisconsin, seemed to have been for naught. The brief hour of progressive Liberal ascendance in state parties and state houses looked to be over just four short years after it started and it began to get Hughes wondering if that might foretell problems for his own Presidency.

This was not to say that he was, or thought of himself as, unpopular. Supportive letters arrived by the bucketloads every day, and when greeting troops he was met with friendly astonishment. But the heaviness of the project at hand, and the sense that his efforts to center the Liberal Party at the heart of the American political and philosophical spectrum rather than trying to dig in its heels against the steady tide that was washing away the triumphs of Blainism [1] was perhaps not imbued with the certainty and permanency that he had once hoped. Despite the encouragement of Root, and the knowledge that he would see some changes in his Cabinet come January, Hughes took the shellacking at the state level as a partial indictment of himself, and the heaviness which he carried only worsened..."

- American Charlemagne: The Trials and Triumphs of Charles Evans Hughes

"...both Berger and Boyce were foreign-born, probably no coincidence in their deep connection to immigrant communities in their home districts [2], and thus had a more worldly sense of perspective on the setbacks and the advances that the Socialists were making. It became immediately clear to them that the "Haywood Headache" in the West was a major problem; Bill Haywood's imperious attitude within the WFM, his scornful attitude towards participation in the electoral process, and the thuggish behavior of many of his miners at a time when the labor movement was shifting in a more conservative direction even outside of the establishmentarian AFL had served to alienate him from some of his supporters and made his name toxic to members of the public, especially out West where he was a mainstay of some notoriety in public life. With Debs' focus having turned exclusively to the advantages the ARU could wring from the nationalization of the railroad and the genuine opportunity to effect an industrial union [3] the result was that Berger especially became the centrifugal force of not just the electoral arm of American socialism but increasingly the movement itself (Moyer's decision to leave politics to focus on labor organizing exclusively helped Boyce become the chief figure of the Socialist Party in the West, at that), and Berger looked to the states for inspiration.

It was at the municipal level that the Socialists were seeing their greatest success, and 1914 may have underlined that story more than any other time as they shifted away from their base in the mining districts of the West. In New York, three prominent candidates had sought Congressional office - former Representative Morris Hillquit and newcomers Meyer London and Fiorello LaGuardia - with London triumphing and Hillquit and LaGuardia falling just shy of defeating incumbent Democratic Congressmen. This suggested to Berger that over a decade since the United Labor Party had collapsed along with the death of its once-champion Henry George [3], the ground was perhaps ripe for Socialism in the biggest city in America, and began pondering who might carry the torch for the party in 1917.

The Northwest was where the real action lay, though. Late 1913 and 1914 had seen three Socialists - former Democrat Harry Lane and longtime Socialists Hulet Wells and David Coates - elected as mayors of Portland, Seattle and Spokane, respectively; together, these were the three biggest cities in the Northwest and all three hotbeds of political radicalism. The Northwest was a strange place, a funhouse mirror microcosm of politics elsewhere. The Democrats dominated rural districts and the machines based out of cities, but had increasingly come under fire for corruption, the operation of gambling dens and illicit saloons, and organizing thugs to attack labor organizers or other disfavored groups, particularly in Seattle, where the vehemently anti-Socialist newspaper publisher Alden Blethen used his Seattle Times to gin up mobs and provoke violence. With the hostile terrain of much of the Inland Northwest in the times before the dam projects undertaken in the 1920s and early 1930s provided mass irrigation, though, Democrats were dependent on city voters, voters now increasingly frustrated with their public officials. Socialists could take advantage of that in the cities, but only to a point.

In Oregon and Washington, at the time though, there was a novelty known as fusion voting, in which parties could cross-endorse and run a single candidate on two lines, and the curious alliance of Socialists, pro-Prohibition "dry" Democrats, and Liberals could unite together against the urban and rural machines that controlled the states. In Seattle proper, this had some staying power as the Municipal League, which powered Wells' lengthy mayoralties, but elsewhere it was a curiosity that only occurred briefly in the early-to-mid 1910s. Socialists were too controversial to win statewide in either Washington or Oregon still, and Liberals too nonexistent outside of the cities to make much headway, but together - and by peeling off enough progressive Democratic voters, for actual Democratic politicians never went near fusionism out of fear of angering the machine - they could carry the day, and so they did behind the "Fusion Tickets" of Walter Lafferty and Ole Hanson, who were elected to the Senate in 1914 on the backs of one of the most unique coalitions to ever emerge in American politics. Socialists got their left-wing economic policy, Liberals and Dries got their good government reformism and hostility to the evils of drinking, gambling and whoring - everybody had something to gain by partnering together, different as they all may have been in background and views on capitalism.

It was thus that Berger, who got on well with Lafferty and Hanson but did not precisely endorse fusionism, ingratiated himself with Democratic leadership in the House while much of the party's base in the Northwest was now voting for very left-wing Liberals who were somehow in the same party caucus as men like Boies Penrose and Henry Cabot Lodge. The strange early adolescence of the Socialist Party's role as Congressional kingmaker had arrived..." [5]

- The American Socialists

[1] As covered, Blaine - for better or worse - serves to most Liberals of Hughes' generation and even more so for those older essentially the role Abraham Lincoln did for the Republican Party of OTL from 1860-1910ish. The conservative flank of the Liberals are, really, those men who just simply can't quit the good old Blaine-Hay paradigm they grew up with or came up in the party ranks during, and parties are rarely successful looking backwards rather than forwards. This, here, is how the Liberal dynasty that began in 1880 collapses upon itself entirely, though I'd argue the 1902/04 wipeouts were the real turning point - YMMV!

[2] In case it hasn't been made clear already, Ed Boyce represents Idaho mining country - aka the Panhandle, aka the National Redoubt and playland of America's white nationalist militia movement today (and, incidentally, where my girlfriend grew up). If you don't appreciate the irony of one of the chief Socialists representing Militialand USA, then do you even Cinco de Mayo?

[3] More on this, the effective germination of sectoral bargaining in the USA, in 1915

[4] Remember - he was the Mayor of New York in the mid-1880s back when the KoL was a thing

[5] Toldya it was getting weird. There really were some bizarre ad hoc coalitions of convenience in states where one party was dominant during the Progressive Era, though idk if any of them were quite as weird as "literal socialists and literal laissez-faire bourgeoise managerial types allying against machine bosses"

(Author's Note - one more midterm update coming, an Al Smith specific one, just wanted that in its own post so I can reference the threadmark title in the future.)

Last edited:

I'm enjoying giving so many of these Prairie Populist Dem figures their time in the sun that they didn't get OTL.Nice to see John Burke of Dakota making his apperance in Dakota - he was, in OTL, a pretty damned good Governor and honorable dude (had to be to get elected as a Dem in OTL North Dakota!). I'm looking forward to seeing some of the OTL NPLers poke their heads onto the state and national scene; though, as we've discussed, most will certainly be Socialists in the ATL. This TL will certainly be ... livened up even more by future president Wild Bill Langer(and no, I don't expect him to actually be President- though THAT would be a timeline like no othe!)

On a sidenote, my sleep addled Upper Midwestern brain kept reading FL as "Farm Labor" rather than "Fusion Liberal" and got a bit confused for a while!

I believe, regarding the NPL, that I did elect Art Townley to the Congress as a Socialist (though he may have lost in 1914, since only 6/11 were re-elected)

I think you forgot to threadmark"...made it clear that he opposed the "electoral truce," or at least that Clark and Mann were encouraging it; Norris was not necessarily against it, but was skeptical whether it would be abided and took the dominant results Democrats enjoyed in many states suggested to him that Clark could have won an outright majority for his Speakership had so many state parties not "stood down." Much like his fierce advocacy for worker's compensation, his time would have to wait, but Norris among all others was certainly curious to see what would come of this "hung Congress."

The reality was that not much would change; the thin majority for Clark, and the narrow minority for Mann, meant that both men were returned by their respective caucuses despite some grumbling among the Butlerites on the Liberal side of the aisle, greased along by Mann strategically promising moderate fence-sitters and a handful of amenable Butlerites juicy committee postings after the turnover that had seen as much as a third of the Liberal caucus leave via retirement due to various impacts of the war. The Democratic attrition was milder, and that suited Norris well - he could earn his cachet with the more determined new members and had his reputation intact with the returnees. This knife's-edge Congress meant that one of the two men who effectively served as "co-Speakers" would continue to do so atop the War Committee, and it became relatively clear that it would be Clark - there was, quite simply, no mathematical path for Mann to become Speaker, but Clark did need every vote nonetheless to officially clear the bar that was required by the Constitution.

Enter Victor Berger, the Austrian-born chief Socialist in the House who had just watched half of his miniscule caucus melt away but quite critically still had enough votes to put Clark over the top even if some of his caucus chose to abstain or vote against Clark on the floor. The most critical divide within the American Socialist cause in 1914 was related to its reformist or its revolutionary strains, and to what extent the radical International Workers of the World labor union conglomerate would dictate the Socialist Party's behavior. The election had seemed to answer that question rather definitively - not particularly much. The most hard-left elements of the IWW were largely associated with the Western Federation of Miners, which had frequently clashed with state and governmental authorities in the "mine wars" that had plagued the West for over a decade, and the WFM had just watched a number of its key figures - Charlie Moyer of Colorado and Vincent St. John of Nevada in particular, both being crucial WFM organizers and former Presidents - be turfed out of the House as populist Democrats ran hard in mining and logging districts with transient populations disrupted by the war. One of the survivors, Representative Ed Boyce of Idaho, was himself a former President of the WFM, who had gradually become disillusioned with the practicability of the IWW's revolutionary impulses but had nonetheless remained committed to socialism as an economic philosophy and, via the destruction of his party's caucus in the midterms when the "punch to the left" of the Democrats, now was one of the party's key figures.

All Clark needed, then, were Berger and Boyce provided that no Democrats voted against him or abstained, and Norris was surprised when he was asked to be part of the whip operation to sustain that crucial measure in the months and then weeks ahead of the swearing in of a new Congress, in that role supporting incoming Majority Whip John J. Fitzgerald of New York, a brash but smooth-talking Irish-American who had been chummy with Sulzer and the Tammany Hall machine of his native city alike, and from then on the political fates of "J.J. Fitz" and Norris were intertwined, barreling towards their perch atop the House alongside each other in the 1920s. The decision by Fitz to include Norris in Clark's internal whip operation was partially strategic and partially familiar; the men got on well and Norris regarded the younger but more tenured and senior man to be an unusually honest politician considering that he had emerged out of the viper's den of New York City politics, while Fitz in turn thought of "Honest George" as a man who both he and the Prairie Populists who couldn't see the forest for the trees could trust, and thus Norris was now the liaison between the most progressive agrarian rebels and Clark, a position that gave him a foot in both camps and instantly marked him as a man of tremendous influence at the hingepoint of the Democratic House coalition.

As for Berger, the "Red Kaiser of Milwaukee" understood perfectly well how the game was played. While three of his Socialists were uncommitted (or unpersuaded), Berger promised Clark and Fitz the votes of himself, Boyce and freshman Meyer London of New York (who most certainly needed good relations with Tammany Hall to have any hope of future reelection) in return for the Democrats granting him a position on the powerful Rules Committee and Boyce a seat at the table on the Special Committee on the War - which, in effect, meant that the chair of the Congressional Socialists now had a role in setting the conduct of the whole House, and his lieutenant was the formal tiebreaker whose membership on the War Committee made it a body now with an uneven number of members. While no fan of backroom deals early in his career, Norris came away impressed, and the though the episode as a whole left a bad taste in his mouth for the naked politicking of it, it nonetheless made an impression on him on how "good men can work together in creative ways."

In the end, thanks to Norris' months between the election and the Speaker vote working his colleagues, only three firebrand Democrats, all Kansans and Nebraskans, declined to vote for Clark, but they agreed to abstain from the ballot rather than vote no on the floor - all the other potential rebels voted in favor, and the three holdout Socialsits themselves abstained. This had the effect of considerably lowering the threshold needed to become Speaker, but Clark and Fitz kept their bargain with Berger in the entirety of the 64th Congress. The first, and certainly not last, informal coalition agreement in the United States House had been struck, and Norris had been integral to its formation, which Clark would not soon forget. The Missourian began to rethink his earlier skepticism of Norris and saw him in a new light, as something more than just a Bryanite rabble-rouser from Nebraska.

The ascent to the top of the pyramid, which few could have suspected considering his previous history, had begun in the shadow of certainly one of the strangest and most unique elections in the history of Congress..."

- The Gentle Knight: The Life and Ideals of George W. Norris

"...Hughes, if candid, would admit he didn't particularly care for either of the Senate leaders, finding Penrose sleazy and Kern patronizing, much preferring the moderate chumminess of the Clark-Mann duopoly in the House. "It is perhaps the first time in the history of this Republic," he wrote in amusement to an old law partner, "that the House is the body where comradery rules the day!" To Hughes, the against-the-grain Senate results were of little comfort, nor was the relatively threadbare margin that Clark had eked into the Speaker's chair with. The results in the states were, put simply, disastrous. All the work done at the dawn of the decade by men such as himself and his comrades in New York, or James Garfield in Ohio, or Frank McGovern and Robert LaFollette in Wisconsin, seemed to have been for naught. The brief hour of progressive Liberal ascendance in state parties and state houses looked to be over just four short years after it started and it began to get Hughes wondering if that might foretell problems for his own Presidency.

This was not to say that he was, or thought of himself as, unpopular. Supportive letters arrived by the bucketloads every day, and when greeting troops he was met with friendly astonishment. But the heaviness of the project at hand, and the sense that his efforts to center the Liberal Party at the heart of the American political and philosophical spectrum rather than trying to dig in its heels against the steady tide that was washing away the triumphs of Blainism [1] was perhaps not imbued with the certainty and permanency that he had once hoped. Despite the encouragement of Root, and the knowledge that he would see some changes in his Cabinet come January, Hughes took the shellacking at the state level as a partial indictment of himself, and the heaviness which he carried only worsened..."

- American Charlemagne: The Trials and Triumphs of Charles Evans Hughes

"...both Berger and Boyce were foreign-born, probably no coincidence in their deep connection to immigrant communities in their home districts [2], and thus had a more worldly sense of perspective on the setbacks and the advances that the Socialists were making. It became immediately clear to them that the "Haywood Headache" in the West was a major problem; Bill Haywood's imperious attitude within the WFM, his scornful attitude towards participation in the electoral process, and the thuggish behavior of many of his miners at a time when the labor movement was shifting in a more conservative direction even outside of the establishmentarian AFL had served to alienate him from some of his supporters and made his name toxic to members of the public, especially out West where he was a mainstay of some notoriety in public life. With Debs' focus having turned exclusively to the advantages the ARU could wring from the nationalization of the railroad and the genuine opportunity to effect an industrial union [3] the result was that Berger especially became the centrifugal force of not just the electoral arm of American socialism but increasingly the movement itself (Moyer's decision to leave politics to focus on labor organizing exclusively helped Boyce become the chief figure of the Socialist Party in the West, at that), and Berger looked to the states for inspiration.

It was at the municipal level that the Socialists were seeing their greatest success, and 1914 may have underlined that story more than any other time as they shifted away from their base in the mining districts of the West. In New York, three prominent candidates had sought Congressional office - former Representative Morris Hillquit and newcomers Meyer London and Fiorello LaGuardia - with London triumphing and Hillquit and LaGuardia falling just shy of defeating incumbent Democratic Congressmen. This suggested to Berger that over a decade since the United Labor Party had collapsed along with the death of its once-champion Henry George [3], the ground was perhaps ripe for Socialism in the biggest city in America, and began pondering who might carry the torch for the party in 1917.

The Northwest was where the real action lay, though. Late 1913 and 1914 had seen three Socialists - former Democrat Harry Lane and longtime Socialists Hulet Wells and David Coates - elected as mayors of Portland, Seattle and Spokane, respectively; together, these were the three biggest cities in the Northwest and all three hotbeds of political radicalism. The Northwest was a strange place, a funhouse mirror microcosm of politics elsewhere. The Democrats dominated rural districts and the machines based out of cities, but had increasingly come under fire for corruption, the operation of gambling dens and illicit saloons, and organizing thugs to attack labor organizers or other disfavored groups, particularly in Seattle, where the vehemently anti-Socialist newspaper publisher Alden Blethen used his Seattle Times to gin up mobs and provoke violence. With the hostile terrain of much of the Inland Northwest in the times before the dam projects undertaken in the 1920s and early 1930s provided mass irrigation, though, Democrats were dependent on city voters, voters now increasingly frustrated with their public officials. Socialists could take advantage of that in the cities, but only to a point.

In Oregon and Washington, at the time though, there was a novelty known as fusion voting, in which parties could cross-endorse and run a single candidate on two lines, and the curious alliance of Socialists, pro-Prohibition "dry" Democrats, and Liberals could unite together against the urban and rural machines that controlled the states. In Seattle proper, this had some staying power as the Municipal League, which powered Wells' lengthy mayoralties, but elsewhere it was a curiosity that only occurred briefly in the early-to-mid 1910s. Socialists were too controversial to win statewide in either Washington or Oregon still, and Liberals too nonexistent outside of the cities to make much headway, but together - and by peeling off enough progressive Democratic voters, for actual Democratic politicians never went near fusionism out of fear of angering the machine - they could carry the day, and so they did behind the "Fusion Tickets" of Walter Lafferty and Ole Hanson, who were elected to the Senate in 1914 on the backs of one of the most unique coalitions to ever emerge in American politics. Socialists got their left-wing economic policy, Liberals and Dries got their good government reformism and hostility to the evils of drinking, gambling and whoring - everybody had something to gain by partnering together, different as they all may have been in background and views on capitalism.

It was thus that Berger, who got on well with Lafferty and Hanson but did not precisely endorse fusionism, ingratiated himself with Democratic leadership in the House while much of the party's base in the Northwest was now voting for very left-wing Liberals who were somehow in the same party caucus as men like Boies Penrose and Henry Cabot Lodge. The strange early adolescence of the Socialist Party's role as Congressional kingmaker had arrived..." [5]

- The American Socialists

[1] As covered, Blaine - for better or worse - serves to most Liberals of Hughes' generation and even more so for those older essentially the role Abraham Lincoln did for the Republican Party of OTL from 1860-1910ish. The conservative flank of the Liberals are, really, those men who just simply can't quit the good old Blaine-Hay paradigm they grew up with or came up in the party ranks during, and parties are rarely successful looking backwards rather than forwards. This, here, is how the Liberal dynasty that began in 1880 collapses upon itself entirely, though I'd argue the 1902/04 wipeouts were the real turning point - YMMV!

[2] In case it hasn't been made clear already, Ed Boyce represents Idaho mining country - aka the Panhandle, aka the National Redoubt and playland of America's white nationalist militia movement today (and, incidentally, where my girlfriend grew up). If you don't appreciate the irony of one of the chief Socialists representing Militialand USA, then do you even Cinco de Mayo?

[3] More on this, the effective germination of sectoral bargaining in the USA, in 1915

[4] Remember - he was the Mayor of New York in the mid-1880s back when the KoL was a thing

[5] Toldya it was getting weird. There really were some bizarre ad hoc coalitions of convenience in states where one party was dominant during the Progressive Era, though idk if any of them were quite as weird as "literal socialists and literal laissez-faire bourgeoise managerial types allying against machine bosses"

(Author's Note - one more midterm update coming, an Al Smith specific one, just wanted that in its own post so I can reference the threadmark title in the future.)

How the fuck is William Sprauge still alive? He's been in office for 52 years.

Speaking of Congress have any women been elected yet?

Speaking of Congress have any women been elected yet?

This chapter is missing a thread mark. Just wanted to let you know.Author's Note - one more midterm update coming, an Al Smith specific one, just wanted that in its own post so I can reference the threadmark title in the future.)

I think you forgot to threadmark

Thanks! FixedThis chapter is missing a thread mark. Just wanted to let you know.

He lived to 1915 iOTL!How the fuck is William Sprauge still alive? He's been in office for 52 years.

Speaking of Congress have any women been elected yet?

Oh I know, that’s why I’ve been keeping him in office, to be the Fossil of the Senate.

And I don’t believe any women have been elected yet but that should change soon

So are the Socialists gonna regularly act as coalition makers in House of Representatives in the future?"...made it clear that he opposed the "electoral truce," or at least that Clark and Mann were encouraging it; Norris was not necessarily against it, but was skeptical whether it would be abided and took the dominant results Democrats enjoyed in many states suggested to him that Clark could have won an outright majority for his Speakership had so many state parties not "stood down." Much like his fierce advocacy for worker's compensation, his time would have to wait, but Norris among all others was certainly curious to see what would come of this "hung Congress."

The reality was that not much would change; the thin majority for Clark, and the narrow minority for Mann, meant that both men were returned by their respective caucuses despite some grumbling among the Butlerites on the Liberal side of the aisle, greased along by Mann strategically promising moderate fence-sitters and a handful of amenable Butlerites juicy committee postings after the turnover that had seen as much as a third of the Liberal caucus leave via retirement due to various impacts of the war. The Democratic attrition was milder, and that suited Norris well - he could earn his cachet with the more determined new members and had his reputation intact with the returnees. This knife's-edge Congress meant that one of the two men who effectively served as "co-Speakers" would continue to do so atop the War Committee, and it became relatively clear that it would be Clark - there was, quite simply, no mathematical path for Mann to become Speaker, but Clark did need every vote nonetheless to officially clear the bar that was required by the Constitution.

Enter Victor Berger, the Austrian-born chief Socialist in the House who had just watched half of his miniscule caucus melt away but quite critically still had enough votes to put Clark over the top even if some of his caucus chose to abstain or vote against Clark on the floor. The most critical divide within the American Socialist cause in 1914 was related to its reformist or its revolutionary strains, and to what extent the radical International Workers of the World labor union conglomerate would dictate the Socialist Party's behavior. The election had seemed to answer that question rather definitively - not particularly much. The most hard-left elements of the IWW were largely associated with the Western Federation of Miners, which had frequently clashed with state and governmental authorities in the "mine wars" that had plagued the West for over a decade, and the WFM had just watched a number of its key figures - Charlie Moyer of Colorado and Vincent St. John of Nevada in particular, both being crucial WFM organizers and former Presidents - be turfed out of the House as populist Democrats ran hard in mining and logging districts with transient populations disrupted by the war. One of the survivors, Representative Ed Boyce of Idaho, was himself a former President of the WFM, who had gradually become disillusioned with the practicability of the IWW's revolutionary impulses but had nonetheless remained committed to socialism as an economic philosophy and, via the destruction of his party's caucus in the midterms when the "punch to the left" of the Democrats, now was one of the party's key figures.

All Clark needed, then, were Berger and Boyce provided that no Democrats voted against him or abstained, and Norris was surprised when he was asked to be part of the whip operation to sustain that crucial measure in the months and then weeks ahead of the swearing in of a new Congress, in that role supporting incoming Majority Whip John J. Fitzgerald of New York, a brash but smooth-talking Irish-American who had been chummy with Sulzer and the Tammany Hall machine of his native city alike, and from then on the political fates of "J.J. Fitz" and Norris were intertwined, barreling towards their perch atop the House alongside each other in the 1920s. The decision by Fitz to include Norris in Clark's internal whip operation was partially strategic and partially familiar; the men got on well and Norris regarded the younger but more tenured and senior man to be an unusually honest politician considering that he had emerged out of the viper's den of New York City politics, while Fitz in turn thought of "Honest George" as a man who both he and the Prairie Populists who couldn't see the forest for the trees could trust, and thus Norris was now the liaison between the most progressive agrarian rebels and Clark, a position that gave him a foot in both camps and instantly marked him as a man of tremendous influence at the hingepoint of the Democratic House coalition.

As for Berger, the "Red Kaiser of Milwaukee" understood perfectly well how the game was played. While three of his Socialists were uncommitted (or unpersuaded), Berger promised Clark and Fitz the votes of himself, Boyce and freshman Meyer London of New York (who most certainly needed good relations with Tammany Hall to have any hope of future reelection) in return for the Democrats granting him a position on the powerful Rules Committee and Boyce a seat at the table on the Special Committee on the War - which, in effect, meant that the chair of the Congressional Socialists now had a role in setting the conduct of the whole House, and his lieutenant was the formal tiebreaker whose membership on the War Committee made it a body now with an uneven number of members. While no fan of backroom deals early in his career, Norris came away impressed, and the though the episode as a whole left a bad taste in his mouth for the naked politicking of it, it nonetheless made an impression on him on how "good men can work together in creative ways."

In the end, thanks to Norris' months between the election and the Speaker vote working his colleagues, only three firebrand Democrats, all Kansans and Nebraskans, declined to vote for Clark, but they agreed to abstain from the ballot rather than vote no on the floor - all the other potential rebels voted in favor, and the three holdout Socialsits themselves abstained. This had the effect of considerably lowering the threshold needed to become Speaker, but Clark and Fitz kept their bargain with Berger in the entirety of the 64th Congress. The first, and certainly not last, informal coalition agreement in the United States House had been struck, and Norris had been integral to its formation, which Clark would not soon forget. The Missourian began to rethink his earlier skepticism of Norris and saw him in a new light, as something more than just a Bryanite rabble-rouser from Nebraska.

The ascent to the top of the pyramid, which few could have suspected considering his previous history, had begun in the shadow of certainly one of the strangest and most unique elections in the history of Congress..."

- The Gentle Knight: The Life and Ideals of George W. Norris

"...Hughes, if candid, would admit he didn't particularly care for either of the Senate leaders, finding Penrose sleazy and Kern patronizing, much preferring the moderate chumminess of the Clark-Mann duopoly in the House. "It is perhaps the first time in the history of this Republic," he wrote in amusement to an old law partner, "that the House is the body where comradery rules the day!" To Hughes, the against-the-grain Senate results were of little comfort, nor was the relatively threadbare margin that Clark had eked into the Speaker's chair with. The results in the states were, put simply, disastrous. All the work done at the dawn of the decade by men such as himself and his comrades in New York, or James Garfield in Ohio, or Frank McGovern and Robert LaFollette in Wisconsin, seemed to have been for naught. The brief hour of progressive Liberal ascendance in state parties and state houses looked to be over just four short years after it started and it began to get Hughes wondering if that might foretell problems for his own Presidency.

This was not to say that he was, or thought of himself as, unpopular. Supportive letters arrived by the bucketloads every day, and when greeting troops he was met with friendly astonishment. But the heaviness of the project at hand, and the sense that his efforts to center the Liberal Party at the heart of the American political and philosophical spectrum rather than trying to dig in its heels against the steady tide that was washing away the triumphs of Blainism [1] was perhaps not imbued with the certainty and permanency that he had once hoped. Despite the encouragement of Root, and the knowledge that he would see some changes in his Cabinet come January, Hughes took the shellacking at the state level as a partial indictment of himself, and the heaviness which he carried only worsened..."

- American Charlemagne: The Trials and Triumphs of Charles Evans Hughes

"...both Berger and Boyce were foreign-born, probably no coincidence in their deep connection to immigrant communities in their home districts [2], and thus had a more worldly sense of perspective on the setbacks and the advances that the Socialists were making. It became immediately clear to them that the "Haywood Headache" in the West was a major problem; Bill Haywood's imperious attitude within the WFM, his scornful attitude towards participation in the electoral process, and the thuggish behavior of many of his miners at a time when the labor movement was shifting in a more conservative direction even outside of the establishmentarian AFL had served to alienate him from some of his supporters and made his name toxic to members of the public, especially out West where he was a mainstay of some notoriety in public life. With Debs' focus having turned exclusively to the advantages the ARU could wring from the nationalization of the railroad and the genuine opportunity to effect an industrial union [3] the result was that Berger especially became the centrifugal force of not just the electoral arm of American socialism but increasingly the movement itself (Moyer's decision to leave politics to focus on labor organizing exclusively helped Boyce become the chief figure of the Socialist Party in the West, at that), and Berger looked to the states for inspiration.

It was at the municipal level that the Socialists were seeing their greatest success, and 1914 may have underlined that story more than any other time as they shifted away from their base in the mining districts of the West. In New York, three prominent candidates had sought Congressional office - former Representative Morris Hillquit and newcomers Meyer London and Fiorello LaGuardia - with London triumphing and Hillquit and LaGuardia falling just shy of defeating incumbent Democratic Congressmen. This suggested to Berger that over a decade since the United Labor Party had collapsed along with the death of its once-champion Henry George [3], the ground was perhaps ripe for Socialism in the biggest city in America, and began pondering who might carry the torch for the party in 1917.

The Northwest was where the real action lay, though. Late 1913 and 1914 had seen three Socialists - former Democrat Harry Lane and longtime Socialists Hulet Wells and David Coates - elected as mayors of Portland, Seattle and Spokane, respectively; together, these were the three biggest cities in the Northwest and all three hotbeds of political radicalism. The Northwest was a strange place, a funhouse mirror microcosm of politics elsewhere. The Democrats dominated rural districts and the machines based out of cities, but had increasingly come under fire for corruption, the operation of gambling dens and illicit saloons, and organizing thugs to attack labor organizers or other disfavored groups, particularly in Seattle, where the vehemently anti-Socialist newspaper publisher Alden Blethen used his Seattle Times to gin up mobs and provoke violence. With the hostile terrain of much of the Inland Northwest in the times before the dam projects undertaken in the 1920s and early 1930s provided mass irrigation, though, Democrats were dependent on city voters, voters now increasingly frustrated with their public officials. Socialists could take advantage of that in the cities, but only to a point.

In Oregon and Washington, at the time though, there was a novelty known as fusion voting, in which parties could cross-endorse and run a single candidate on two lines, and the curious alliance of Socialists, pro-Prohibition "dry" Democrats, and Liberals could unite together against the urban and rural machines that controlled the states. In Seattle proper, this had some staying power as the Municipal League, which powered Wells' lengthy mayoralties, but elsewhere it was a curiosity that only occurred briefly in the early-to-mid 1910s. Socialists were too controversial to win statewide in either Washington or Oregon still, and Liberals too nonexistent outside of the cities to make much headway, but together - and by peeling off enough progressive Democratic voters, for actual Democratic politicians never went near fusionism out of fear of angering the machine - they could carry the day, and so they did behind the "Fusion Tickets" of Walter Lafferty and Ole Hanson, who were elected to the Senate in 1914 on the backs of one of the most unique coalitions to ever emerge in American politics. Socialists got their left-wing economic policy, Liberals and Dries got their good government reformism and hostility to the evils of drinking, gambling and whoring - everybody had something to gain by partnering together, different as they all may have been in background and views on capitalism.

It was thus that Berger, who got on well with Lafferty and Hanson but did not precisely endorse fusionism, ingratiated himself with Democratic leadership in the House while much of the party's base in the Northwest was now voting for very left-wing Liberals who were somehow in the same party caucus as men like Boies Penrose and Henry Cabot Lodge. The strange early adolescence of the Socialist Party's role as Congressional kingmaker had arrived..." [5]

- The American Socialists

[1] As covered, Blaine - for better or worse - serves to most Liberals of Hughes' generation and even more so for those older essentially the role Abraham Lincoln did for the Republican Party of OTL from 1860-1910ish. The conservative flank of the Liberals are, really, those men who just simply can't quit the good old Blaine-Hay paradigm they grew up with or came up in the party ranks during, and parties are rarely successful looking backwards rather than forwards. This, here, is how the Liberal dynasty that began in 1880 collapses upon itself entirely, though I'd argue the 1902/04 wipeouts were the real turning point - YMMV!

[2] In case it hasn't been made clear already, Ed Boyce represents Idaho mining country - aka the Panhandle, aka the National Redoubt and playland of America's white nationalist militia movement today (and, incidentally, where my girlfriend grew up). If you don't appreciate the irony of one of the chief Socialists representing Militialand USA, then do you even Cinco de Mayo?

[3] More on this, the effective germination of sectoral bargaining in the USA, in 1915

[4] Remember - he was the Mayor of New York in the mid-1880s back when the KoL was a thing

[5] Toldya it was getting weird. There really were some bizarre ad hoc coalitions of convenience in states where one party was dominant during the Progressive Era, though idk if any of them were quite as weird as "literal socialists and literal laissez-faire bourgeoise managerial types allying against machine bosses"

(Author's Note - one more midterm update coming, an Al Smith specific one, just wanted that in its own post so I can reference the threadmark title in the future.)

I really hope the socialist remain a third party and not be absorbed by the Democrats.

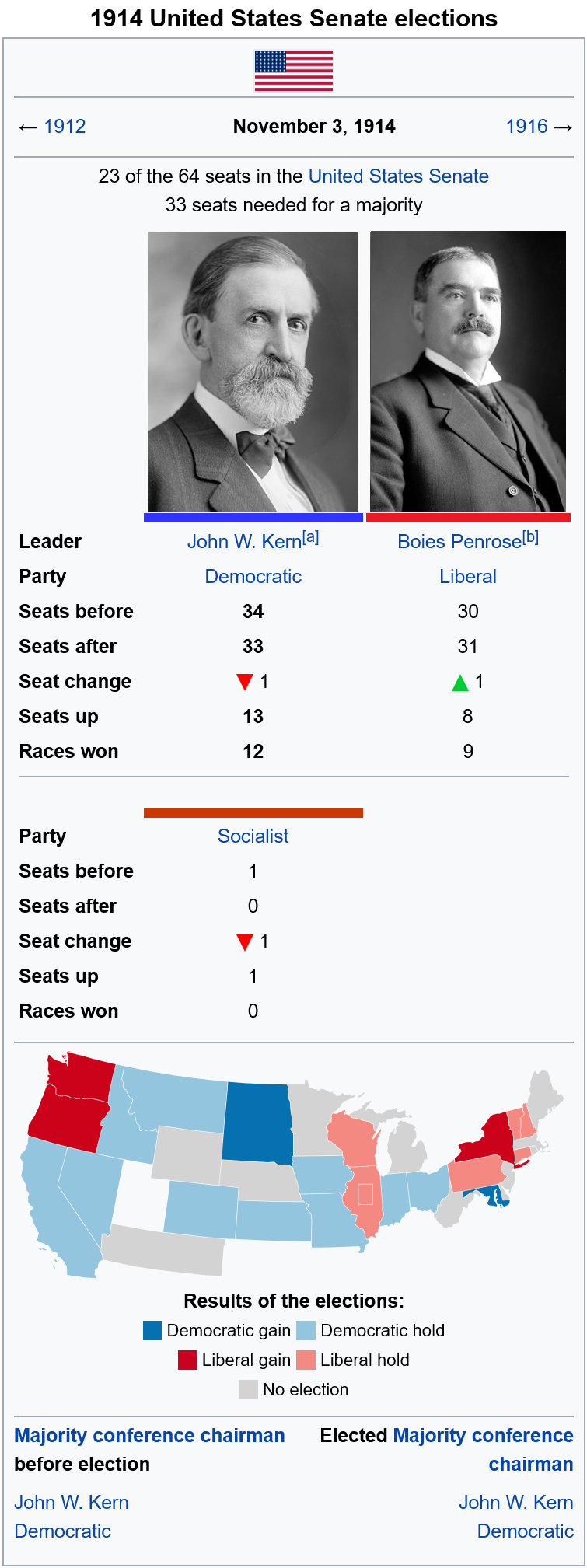

Senate Wikibox (Republicans chinking the Solid Democratic West, and RIP to the Liberals in Maryland for a very, very long time)

So are the Socialists gonna regularly act as coalition makers in House of Representatives in the future?

They’ll be around to present day, though rarely will they be a full on kingmakerI really hope the socialist remain a third party and not be absorbed by the Democrats.

Love to see it visually like that!Senate Wikibox (Republicans chinking the Solid Democratic West, and RIP to the Liberals in Maryland for a very, very long time)

View attachment 804818

FYI, a random fact about Germany around 1909-1910 is that there was an effort to reform the Prussian 3-class voting franchise. It failed because the SPD and liberal-left pushed for universal, unqualified suffrage, whereas the other parties were unwilling to do so - despite even the DKP being willing to support a relatively fairer plural-voting system.

Fun updates! Let's dig into them.

So that now makes at least four different third parties in the timeline who exist solely to take away votes from Democrats. United Labor 1882-1888, the Populists 1890-1900, the Socialists 1902 onward, and now these "Fusion Liberals." That doesn't count the other left-wing parties like Republican-Labor, Anti-Monopoly, or the Greenbacks - just the "major" third parties since the Liberals fully took over from the Republicans.

It really is kind of incredible how the Liberals get all the benefits of having a progressive wing, yet they never suffer any electoral drawbacks by having their progressive voters switch to third parties to indirectly benefit Democrats. Only Democratic-aligned left wingers get sucked in by the siren song of third parties while Liberal left-wingers loyally vote Team L election in and election out. Crazy how they're able to thread the needle like that!

I'm not going to sit here and say that Democrats are perfect, or even clsoe to perfect, but these Fusion purists need to realize that a vote for Hanson and Lafferty, no matter what line on the ballot they sit on, is a vote for reactionaries like Penrose and Henry Cabot Lodge to run the Senate. Then again, some of this is my own damn fault for bringing your past words to light so I guess I get what I deserve 🤷♂️

Moving onward from the bloodbath out west...

What the hell happened in New York? Wadsworth was previously described as "...probably too conservative to elected even in a good year." Yet he won in a state where Democrats otherwise made gains? Huh?

Glad to see my home-state Illinois Democrats rise from their decade-long stupor and actually make gains, especially in a state where progressive and conservative Liberals are openly feuding with each other over the levers of power. It wasn't enough to win a Senate seat or the Governorship of course but hey, progress is progress.

On the one hand, Hughes potentially not running again in 1916 makes sense. The guy made a habit OTL of peacing out whenever he was in office/Cabinet too long, and I can't imagine he's having a grand old time being President of a country that's had huge chunks of territory put to the sword and millions killed or wounded. It also makes narrative sense as to why every single source in this timeline uncritically worships the ground the man walks on - there's nothing Presidential historians love more than a guy who steps down from the big job. It does help Hughes's reputation to not be running the country when the shit hits the fan in 1918 or so.

On the other hand, Hughes (potentially) not running in 1916 makes the Democrats losing that much worse. Given his secular sainthood ITTL I can see some random Democrat losing to Hughes, it makes sense to not switch horses midstream and all that. But losing to Hughes's replacement in an open election? That's a disaster for the party.

So that now makes at least four different third parties in the timeline who exist solely to take away votes from Democrats. United Labor 1882-1888, the Populists 1890-1900, the Socialists 1902 onward, and now these "Fusion Liberals." That doesn't count the other left-wing parties like Republican-Labor, Anti-Monopoly, or the Greenbacks - just the "major" third parties since the Liberals fully took over from the Republicans.

It really is kind of incredible how the Liberals get all the benefits of having a progressive wing, yet they never suffer any electoral drawbacks by having their progressive voters switch to third parties to indirectly benefit Democrats. Only Democratic-aligned left wingers get sucked in by the siren song of third parties while Liberal left-wingers loyally vote Team L election in and election out. Crazy how they're able to thread the needle like that!

I'm not going to sit here and say that Democrats are perfect, or even clsoe to perfect, but these Fusion purists need to realize that a vote for Hanson and Lafferty, no matter what line on the ballot they sit on, is a vote for reactionaries like Penrose and Henry Cabot Lodge to run the Senate. Then again, some of this is my own damn fault for bringing your past words to light so I guess I get what I deserve 🤷♂️

Moving onward from the bloodbath out west...

What the hell happened in New York? Wadsworth was previously described as "...probably too conservative to elected even in a good year." Yet he won in a state where Democrats otherwise made gains? Huh?

Glad to see my home-state Illinois Democrats rise from their decade-long stupor and actually make gains, especially in a state where progressive and conservative Liberals are openly feuding with each other over the levers of power. It wasn't enough to win a Senate seat or the Governorship of course but hey, progress is progress.

On the one hand, Hughes potentially not running again in 1916 makes sense. The guy made a habit OTL of peacing out whenever he was in office/Cabinet too long, and I can't imagine he's having a grand old time being President of a country that's had huge chunks of territory put to the sword and millions killed or wounded. It also makes narrative sense as to why every single source in this timeline uncritically worships the ground the man walks on - there's nothing Presidential historians love more than a guy who steps down from the big job. It does help Hughes's reputation to not be running the country when the shit hits the fan in 1918 or so.

On the other hand, Hughes (potentially) not running in 1916 makes the Democrats losing that much worse. Given his secular sainthood ITTL I can see some random Democrat losing to Hughes, it makes sense to not switch horses midstream and all that. But losing to Hughes's replacement in an open election? That's a disaster for the party.

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: