Chapter 67: Sardinia Alliances

Chapter 67: Sardinia Alliances:

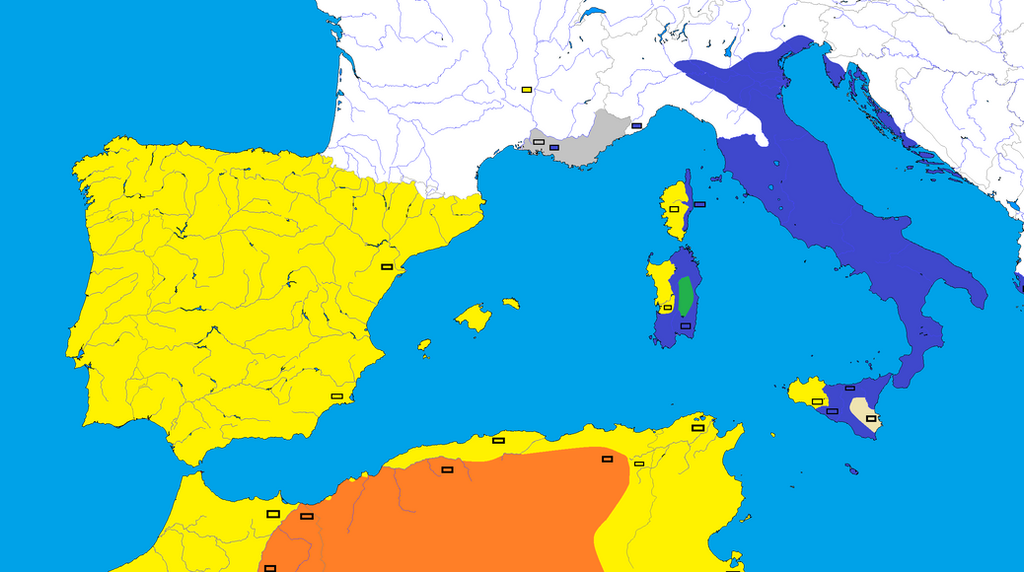

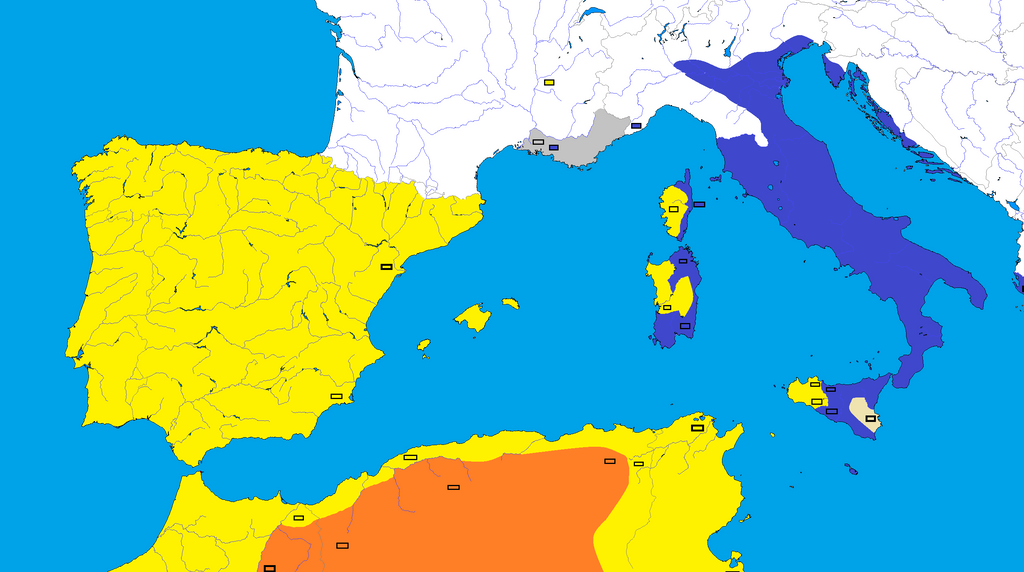

In Sardinia Hasdrubal the Bald had lost many troops and was very sure, that the Romans under Quintus Mucius Scaevola would soon advance on his army and the rebellious western and northern cities, loyal to Carthage. While he now controlled the western coastal road from Othoca over the revolutionaries capital Cornus along Bosa up to Carbia, Nura and Turris Libisanus he heard news that the Romans had landed troops on the northeast in Olbia. Hasdrubal knew that this army could take the western route to Luguido and Castra Felicia, advancing to Hafa from where they could turn north against Turris Libisanus or south over Molaria, Mocopsisa to Forum Traiani. From this city they could come down the river Thyrsius to directly attack Othoca or guard it to use it as a direct link over Biora to Carales in the south. The more western road from Carales over Aquae Neapolitanae or Othaca in the northeast had a crossroad to the left between both cities outside of Carthaginian controlled Sardinia. It led towards the southwestern cities of Neapolis, Metalla, Populum and Tegula, then turned east along the southern coast over Bita and Nora back to Carales. Because of this the southwestern roman loyal territories could easily be supplied from at least one road, making it hart for Hasdrubal to attack them without fearing to get surrounded, as long as he didn't control Aquae Neapolitanae and block the northern part of this circle road. At the moment Hasdrubal had other plans then to advance south to Caralis again and encircle the western loyal Roman cities, because of his recent losses in battle. Hasdrubal the Bald planned to send reinforcements to Turris Libisanus over the western coastal road, because the city could now be attacked from the south and the east. Hasdrubal also took preparations to march along the Thyrsius river towards Forum Triarum, so he could cut of the northern from the southern Roman army and by doing so secure the flank of Othoca, Turris Libisanus and Cornus. This was his main plan, because his emissary contacted the Balari, Ilienses and Ciculensii, mountain tribes of the central island that fought Rome now the same way they before had fought Carthage's colonies and foothold on the coast. Hasdrubal hoped that together with these tribes, he could cut the Roman part of Sardinia in half, advance towards the eastern coast and after that easily overrun the then remaining Roman territories in the northeast and south. Quintus Mucius Scaevola in the meantime planned to let part of his army march the middle road from the south to the north, to unite with the northeastern roman army and to crush the rebels on the northern coast around Turris Libisanus, Nura and Carbia.

In Sardinia Hasdrubal the Bald had lost many troops and was very sure, that the Romans under Quintus Mucius Scaevola would soon advance on his army and the rebellious western and northern cities, loyal to Carthage. While he now controlled the western coastal road from Othoca over the revolutionaries capital Cornus along Bosa up to Carbia, Nura and Turris Libisanus he heard news that the Romans had landed troops on the northeast in Olbia. Hasdrubal knew that this army could take the western route to Luguido and Castra Felicia, advancing to Hafa from where they could turn north against Turris Libisanus or south over Molaria, Mocopsisa to Forum Traiani. From this city they could come down the river Thyrsius to directly attack Othoca or guard it to use it as a direct link over Biora to Carales in the south. The more western road from Carales over Aquae Neapolitanae or Othaca in the northeast had a crossroad to the left between both cities outside of Carthaginian controlled Sardinia. It led towards the southwestern cities of Neapolis, Metalla, Populum and Tegula, then turned east along the southern coast over Bita and Nora back to Carales. Because of this the southwestern roman loyal territories could easily be supplied from at least one road, making it hart for Hasdrubal to attack them without fearing to get surrounded, as long as he didn't control Aquae Neapolitanae and block the northern part of this circle road. At the moment Hasdrubal had other plans then to advance south to Caralis again and encircle the western loyal Roman cities, because of his recent losses in battle. Hasdrubal the Bald planned to send reinforcements to Turris Libisanus over the western coastal road, because the city could now be attacked from the south and the east. Hasdrubal also took preparations to march along the Thyrsius river towards Forum Triarum, so he could cut of the northern from the southern Roman army and by doing so secure the flank of Othoca, Turris Libisanus and Cornus. This was his main plan, because his emissary contacted the Balari, Ilienses and Ciculensii, mountain tribes of the central island that fought Rome now the same way they before had fought Carthage's colonies and foothold on the coast. Hasdrubal hoped that together with these tribes, he could cut the Roman part of Sardinia in half, advance towards the eastern coast and after that easily overrun the then remaining Roman territories in the northeast and south. Quintus Mucius Scaevola in the meantime planned to let part of his army march the middle road from the south to the north, to unite with the northeastern roman army and to crush the rebels on the northern coast around Turris Libisanus, Nura and Carbia.

Last edited: