Boldly Going Part 11

During her launch,

Enterprise had carried a level of payload never imagined for the Space Shuttle. In a certain sense, the 150 metric ton payload of

Enterprise on STS-37R exceeded the maximum ever achieved by the mighty Saturn V--a rocket well and truly demonstrated capable of the lunar mission, and widely baselined for NASA’s internal Mars studies in the 1960s and 70s. Moreover, whatever the worries about risks and delays before launch, the station had successfully flown just weeks before the National Space Council gathered to begin work on their 90-day study. As they started,

Space Station Enterprise was now orbiting overhead waiting to be exploited, turned into a space station larger than almost any NASA had dared to dream of...and several years before those other studies could have been imagined to have flown. In laying out their analysis for the 90-day study, Administrator Truly and Vice President Quayle would try to seek similar areas where the success of the program could be ensured by seeking lower cost, lower complexity solutions.

Enterprise provided an example of how, through careful selection, such solutions - though perhaps less optimal than a clean sheet design - could nevertheless meet the agency's needs. As NASA struggled to conceive a plan which could achieve ambitious goals for the future on a limited budget, such minimization of complexity in the near term could help ensure the success of ambitions for the future: the full conversion of

Enterprise into a permanently-crewed outpost, beginning a lunar program with the aim to place the United States and any willing allies back on the path to the moon within the 1990s, and finally laying the groundwork to allow a future program for Mars.

Enterprise’s success from aiming for the near and medium-term and allowing long-term plans to be developed and executed more fluidly in response to developments would provide a model for handling Mars: no concrete budget or schedule deadlines would be provided. Instead, goals and technologies for the program would be allowed to flow from successes encountered or hardware developed in lunar planning. Thus, the full options presented to Congress with cost and schedule projections would focus on the first two areas: the station and the moon. To meet the goals for space station operations and lunar explorations, NASA again drew on the experience of

Enterprise to win approval for a program Congress might not have been willing to approve if not couched as a fallback option. Instead of a single monolithic plan, NASA presented several options varying in level of funding, schedule, and architecture. It would fall to Congress to select from among these recommendations.

The state of

Space Station Enterprise planning before Bush’s “Space Exploration Initiative” bears some review. At the start of the project in 1983,

Enterprise had been intended as a limited-duration expedient. While international partners like ESA were involved from the start, initially plans for broader involvement by ESA and the Japanese human spaceflight agency NASDA (later merged into JAXA) were focused on successor stations, more like the originally considered “Space Station Freedom” concepts: large, multipurpose, multi-module stations which would be centers of orbital operations and infrastructure. As the Space Shuttle program had ramped up and

Space Station Enterprise itself had proved more challenging than expected, it had gradually become clear that SSE itself was shutting out such stations from existing on schedule. By 1986, ESA and NASDA realized that if they wanted to work with the Americans on a large station program, it would have to be with the expansion of

Enterprise. Thus, though the hardware for

Enterprise’s core modules saw little change even as their launch date slipped by two years, the period between the loss of

Discovery and

Enterprise’s launch in 1989 saw NASA and its international partners working out preliminary concepts for expanding the station to fill much of the role the Space Operations Center-style

Freedom had originally been conceived to address.

While

Enterprise’s LOX tank volume of 560 cubic meters made habitat space readily available,

Enterprise’s laboratory capacity was more limited. Only Spacelab Instrument Rack drawers could be transferred into the station, around the intertank passages, and on through the mid-deck of OV-101 to the

Leonardo Laboratory Module (LLM). Larger installations like the proposed “International Standard Payload Rack” (ISPR) could not be moved given the small hatches subdividing the station. Additionally, the station had only two ports for visiting vehicles and future expansion. The international partners and NASA had come to rough agreement on methods for solving these issues: ESA and Japan would both be able to launch laboratory modules aboard the Space Transportation System and the crew to serve them, in exchange for providing hardware which would contribute to the station’s capabilities and expansion. NASA, for their part, would provide a LOX tank fully outfitted as a habitat, with internal partitions, hygiene systems, and the life support equipment for the station as a whole. However, given the 36” diameter hatch into the LOX tank, the ability to use the LOX tank as laboratory space would necessarily be limited to Spacelab-standard drawer modules. Thus, they would become a defacto standard for the many pieces of modular equipment the LOX tank would house, as they already were in the existing

Leonardo laboratory. However, the experiments which could be housed in such SIR drawers were relatively rudimentary compared to the larger mass and volume available to ISPR-mounted experiments. Only the newer modules would be capable of both housing such racks and moving them through the new, larger vestibule hatches to or from other modules or visiting vehicles. Japan was tentatively agreed to be providing the two node modules which would provide the space for the station’s expansion. Most critically, in the wake of the extended stand-down of the Space Shuttles following

Discovery’s loss, ESA would provide the on-orbit crew lifeboat which would ensure any astronauts on the station or a visiting Space Shuttle crew would always have a ride home in the event of further issues with the Space Shuttle.

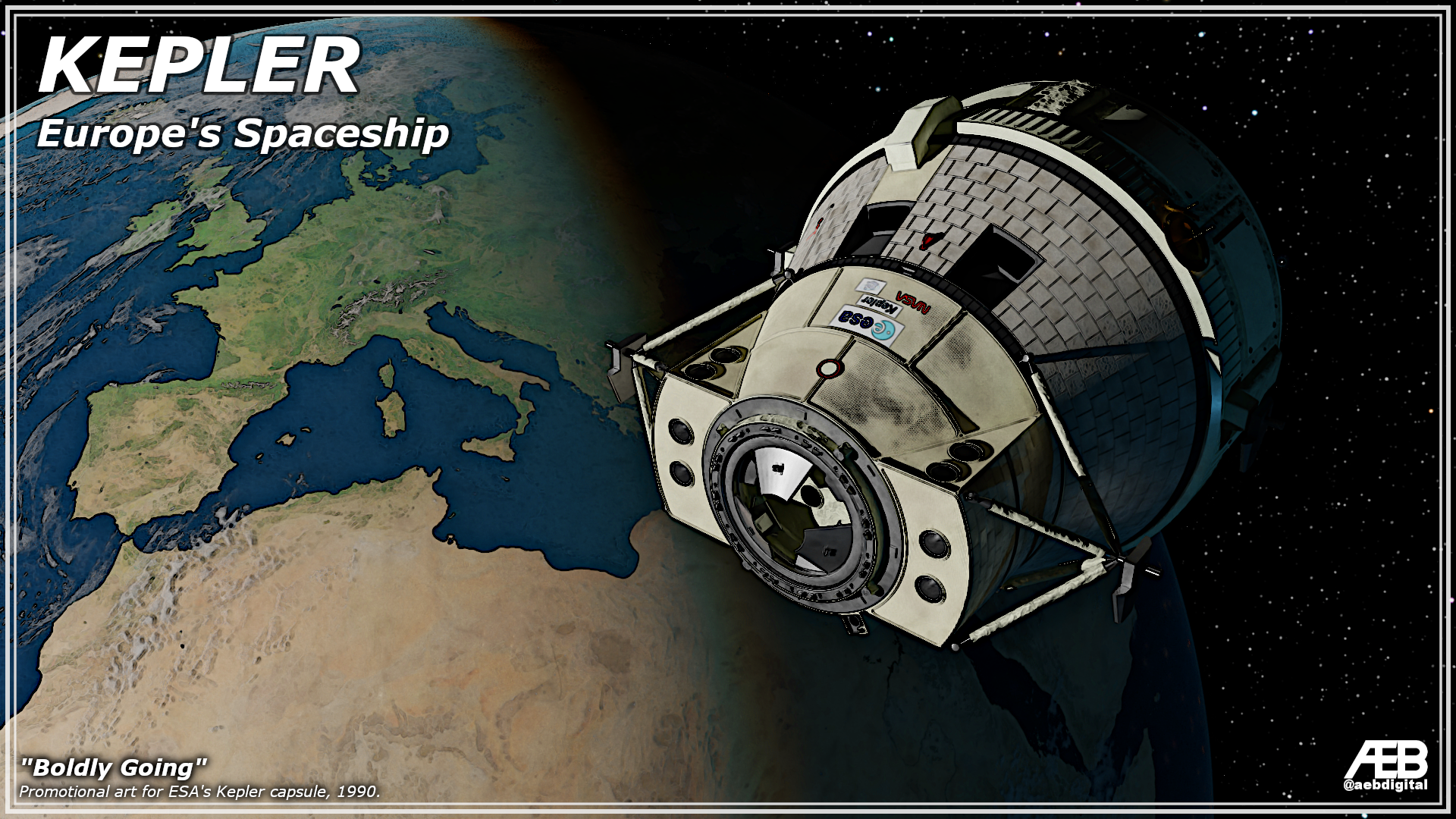

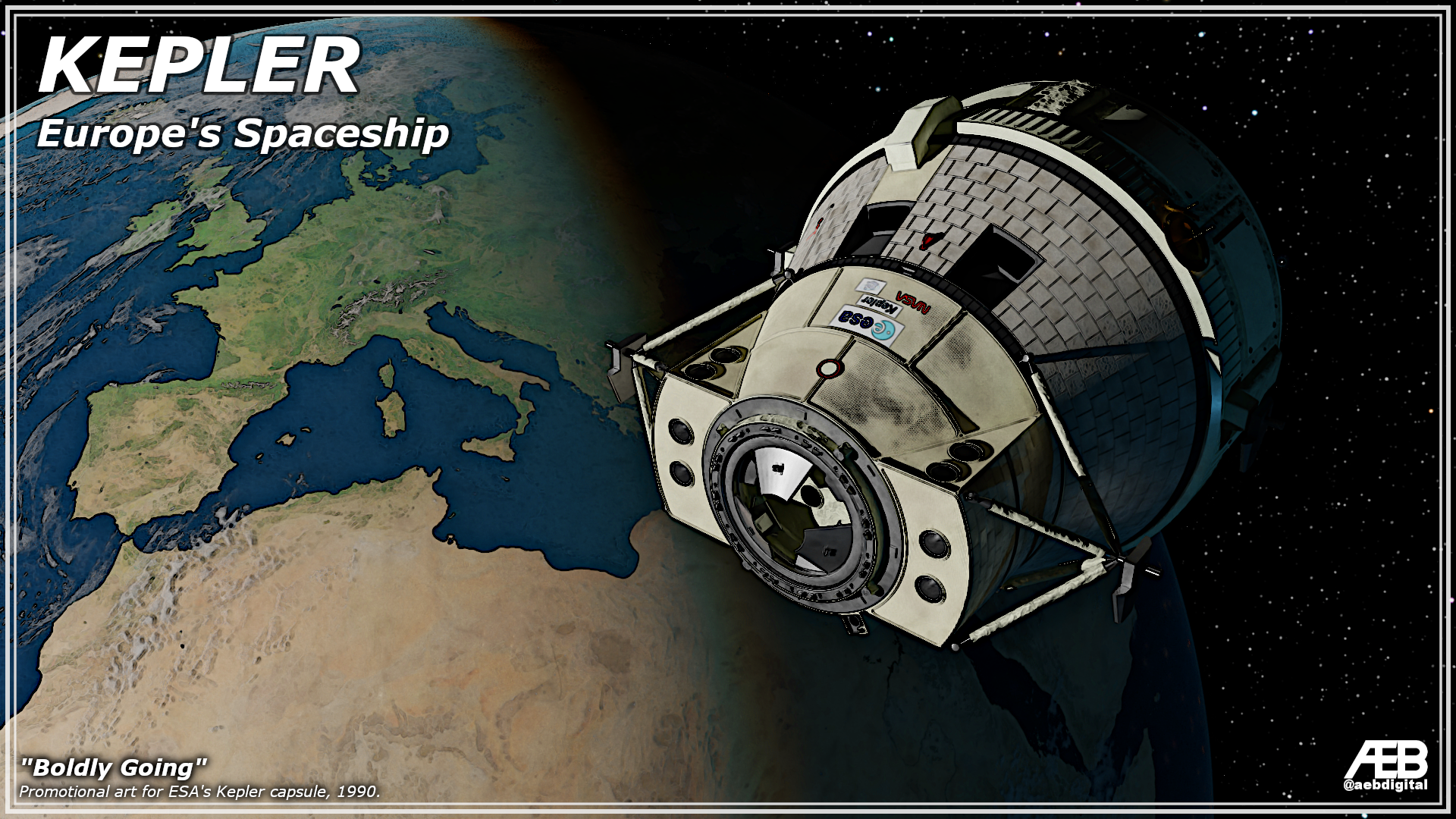

These plans were fairly advanced by 1989 and had developed significant support within both American and international agencies and governing bodies. It was anticipated that only the station core’s launch delayed formal support from the White House. ESA had gone so far as to shape decisions about their independent human spaceflight plans around

Enterprise requirements. In order to be ready for a role as a space station lifeboat. After extended and contentious debate, ESA had decided against the French “Hermes” spaceplane proposal as their primary crew vehicle. Instead,in 1987 they had selected an Italian design for a “Multi-Role Recovery Capsule,” based heavily on the British “Multi-Role Recovery Capsule” proposal of the same name. The capsule was anticipated to serve as a “cheap and cheerful” solution to the combined mission of an

Enterprise lifeboat and independent crew vehicle capable of launching on their existing Ariane 44L lifter. In a sop to French pride wounded by selecting an Italian implementation of a British concept over the wishes of the French space agency, CNES, France was approved to build both the new Ariane 5 launch vehicle and a logistics vehicle capable of fully utilizing it, and would also supply the thermal protection system for the new MRRC. While ESA would have preferred to have both the capsule and the more ambitious spaceplane, the switch to the less ambitious capsule as the sole crew vehicle for Europe would reduce costs and free up budget for the assumed-imminent

Enterprise laboratory modules. Japan was likewise conducting advanced studies on their planned laboratory module. Thus, even by 1989 international partners had begun to shape their future space programs around assumptions for

Space Station Enterprise’s utilization and growth. Bush’s refocus of NASA’s priorities on the moon threw these plans into jeopardy and led to massive international confusion.

Artwork by:

@nixonshead (

AEB Digital on Twitter)