Boldly Going Part 7

With the successful single launch of OV-101 complete, the flight of

Space Station Enterprise seemed to clear years of doubts about the program in a single shot. Cheers erupted in Houston, Florida, and in the homes and offices of hundreds of thousands of people who had worked on the station as the ground controllers verified the station was talking to TDRS, then as that relay carried along confirmation that

Enterprise had completed the first OMS burn to stabilize her orbit. Soon, a second signal carried confirmation that the orbiter-turned-station’s computers had activated the payload bay door actuators, and onboard cameras downlinked the welcome image of

Enterprise’s doors swinging smoothly open in space for the first time. However, the last event on the launch timeline was the most critical of them all--no one on the ground could relax until the computers completed their first programmed activities and deployed the station’s keep alive solar arrays. Too many still remembered that

Skylab’s panels had been the source of its problems, and were bracing themselves for a desperate effort to get off

Atlantis’s STS-38R launch if anything failed. As TDRS passed the station from satellite to satellite, the downlink capability occasionally faltered. The moment of solar array deployment found the station passing through a window capable of transmitting only telemetry, which recorded the signals indicating that the two solar array sections facing up and out of the bay should have begun to deploy. The Marshall and Houston teams held their breath in spite of the early indications. Deployment motors being triggered meant little, and nothing was for sure until the panels were seen to be open and providing power.

Finally, the downlink flickered back into high-rate capability, and the video picked back up to capture the station’s panels cleanly extending from the Shuttle’s payload bay. Even knowing that the process of fully deploying the keep alive panels would take another half an hour, Houston’s mission control team erupted into cheers--the most critical aspects of deployment were already behind them. Soon, the panels were extended and locked, and life-giving electrical power was beginning to top off the station’s batteries.

Space Station Enterprise had reached orbit successfully and now began her service in space. President George H.W. Bush and Former-President Reagan met with Administrator Richard Truly for photographs and speeches commemorating the success of the program. Former-President Reagan’s speech was particularly memorable, as he marked the

Space Station Enterprise program’s success as a “Symbol of American Freedom and Enterprise,” comparing it favorably to the capabilities of the Soviet

Mir. President Bush’s remarks were more limited, hailing the success, but his speechwriting team had concentrated their superlatives in space for later that month, when they were preparing to announce a major new initiative in exploration. For the moment, the legacy of

Enterprise’s launch was marked more by the former president who had initiated it than by the President who would shape its utilization.

With

Enterprise’s solar arrays deployed and all STS-37R ascent activities completed nominally, the need for a rushed launch of

Atlantis and STS-38R for a mission to “Save Enterprise” as Pete Conrad had once raced to “Save Skylab” was gone. This came as a relief, as unexpectedly poor weather at the Trans-oceanic Abort Landing (TAL) sites haunted

Atlantis during the STS-37R countdown. Several press questions and counterfactual what-ifs have hinged on whether NASA would have risked the launch anyway, given the tiny window during launch where such a transatlantic abort was needed and that

Space Station Enterprise’s success might have hung in the balance. Then and now, the official NASA stance was and has remained that the safety lessons of

Discovery for risk versus reward were clear. Finally, the weather front passed Spain and Morocco, and the first countdown for STS-38R took place on the morning of July 9th. For less complex missions, NASA had cut backup crew assignments prior to the

Discovery disaster. Only mission-specific personnel like Payload Specialists were assigned specific backups. Others roles like mission specialists and pilots were assumed to be able to be pulled at need from the general astronaut pool for any specific mission. However, the

Space Station Enterprise activation and checkout mission had enough mission-specific complexities driving increased training requirements for the crew that NASA had scheduled full prime and backup crews even before

Discovery’s loss.

When first planned in 1986, John Young had assigned himself as commander of the outfitting crew, continuing his record of seeing off the first mission of each new type of module launched aboard Shuttle, including the original STS-1 flight, the STS-9 mission which debuted Spacelab, and the deployment of the Hubble Space Telescope aboard STS-61-J. However, his outspoken critique of NASA management in the wake of the

Discovery disaster lead to Young’s promotion out of the astronaut office, effectively removing him from day-to-day management and more relevantly cutting him from the active flight list. He had already personally recruited Joe Engle as the backup commander, and intervened to persuade Engle (who had been considering retiring from spaceflight after the disaster) to instead make one final flight as prime commander for the mission which would commission

Space Station Enterprise. Engle’s record was long: three suborbital X-15 flights over 50 miles, a near-miss with lunar missions aboard Apollo 17 which saw him bumped for geologist Harrison Schmitt, and two previous Space Shuttle commands. Moreover, Engle had even flown

Enterprise herself in the approach and landing tests of 1977. With the two-year flight stand-down and shifting assignments following the planned Return to Flight, Engle would have his pick of the astronaut corps for the prime crew for the

Space Station Enterprise activation mission.

As a result, the rest of the

Atlantis flight crew was similarly experienced, including several who had flown multiple Shuttle missions. Experience with the Spacelab module was also sought, given its contributions to the

Leonardo Laboratory Module. Pilot Steven Nagel was on his third spaceflight, having previously flown with Spacelab aboard STS-61-A in 1985. On his first spaceflight, he had also had experience with the Robotic Manipulator System (Canadarm) as a mission specialist aboard STS-51-G. On that flight, he had helped use the arm to deploy and then retrieve the Spartan 1 free-flying astronomy satellite. The senior astronaut in the crew by time in space, however, was the prime crew Mission Specialist 1, Owen Garriott. Garriott’s time in the astronaut corps dated back to Apollo, and his experience with Skylab had led to him being appointed as an astronaut liaison to the

Space Station Enterprise Program office, providing recommendations for designing the station’s interior for long-duration space operations and consulting on what could be expected for astronauts outfitting a space station while in orbit on missions measuring not days or weeks, but months. There was no one on the flight list more experienced with

Enterprise’s new incarnation, and Garriott had been a natural for Young to recruit for the prime crew in 1986. Garriott had eagerly leapt at the chance to implement the results of his hard work by flying to his second space station and adding more days to his existing record: 59 days from his time on Skylab and 10 days from his flight aboard STS-9 with the Spacelab debut. After

Discovery, Garriott had (like Engle) been considering retirement, but John Young’s offer to keep him on the

Enterprise deployment prime crew had been irresistible for a man who had thoroughly enjoyed his time aboard Skylab more than a decade before. Garriott delayed his retirement by two years to see the mission completed.

Two more veteran Mission Specialists joined the final STS-38R prime crew. The first was Mission Specialist 2 Norman Thagard, who had already flown on three Shuttle missions. This record, accumulating seventeen days in space, included a Spacelab flight, the Galileo deployment mission STS-61-G, and the complex RMS operations of STS-7. As a licensed physician, Thagard would also provide on-orbit monitoring of the crew’s health during one of the longest and most intense Shuttle flights since the program’s start. Mission Specialist 3 on the STS-38R prime crew ended up being Kathryn Sullivan, who had flown EVA during the Hubble deployment on STS-61-J. While Young had slotted her into the prime crew without certainty of her being able to take on the complexity of the

Enterprise deployment flight less than a year after the Hubble launch, she was readily available with the additional two-year stand-down. Sullivan had spent the time reviewing EVA procedures for the deployment of

Enterprise cargo bay systems and the confirmation of passivating and sealing the massive oxygen and hydrogen tanks of ET-007 both with Garriott and with the last American on STS-38R. This was Mission Specialist 4, rookie Pierre Thuot, who would complete the Extra-Vehicular and Intra-Vehicular Activity specialist team. The final crew member would be the first international visitor to

Space Station Enterprise, Ulf Merbold of Germany representing the European Space Agency as a Payload Specialist, drawing on his previous flight with Spacelab. It was a mark of the critical nature of the program that all but one of the crew had previously flown to space, and Engle had trained his crew rigorously for their purpose.

All told,

Atlantis carried up seven crew members on her STS-38R mission. The planned mission duration would be 11 days, one of the longest Shuttle missions to date. In the future,

Atlantis would be able to draw on

Space Station Enterprise to stretch her orbital endurance, using a new system which would allow

Atlantis to draw power from the station. In time, all of the remaining orbiters would receive the modification, but

Atlantis’ construction after the program’s approval meant she included the capability from the day of her rollout at Palmdale. The capability would not be used on this flight, at least not as originally intended. Still, the fifth mission for the youngest orbiter in the fleet was in many ways what she in particular and her kind in general had been built for: working with a space station for the servicing and deployment of complex payloads in space.

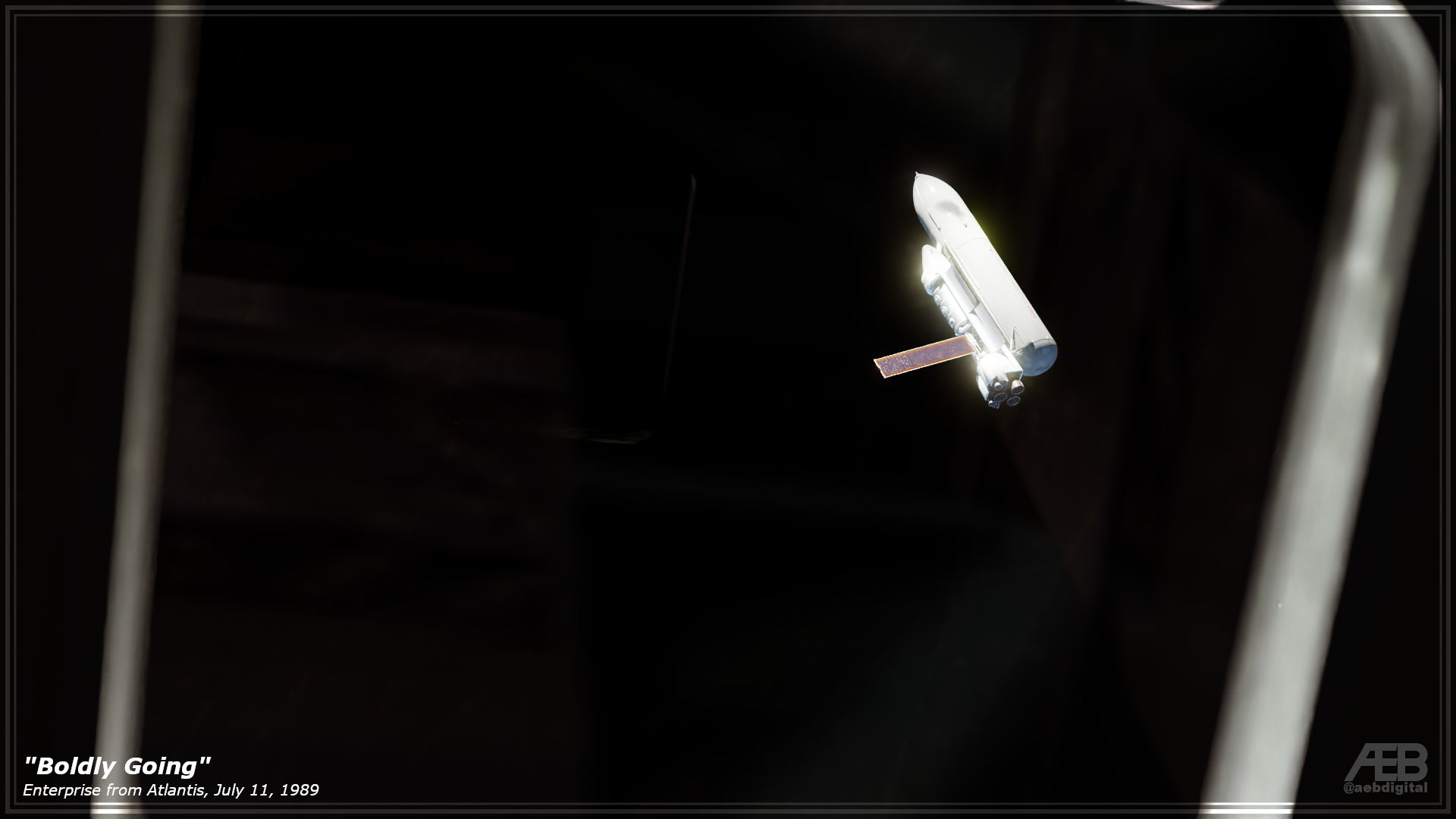

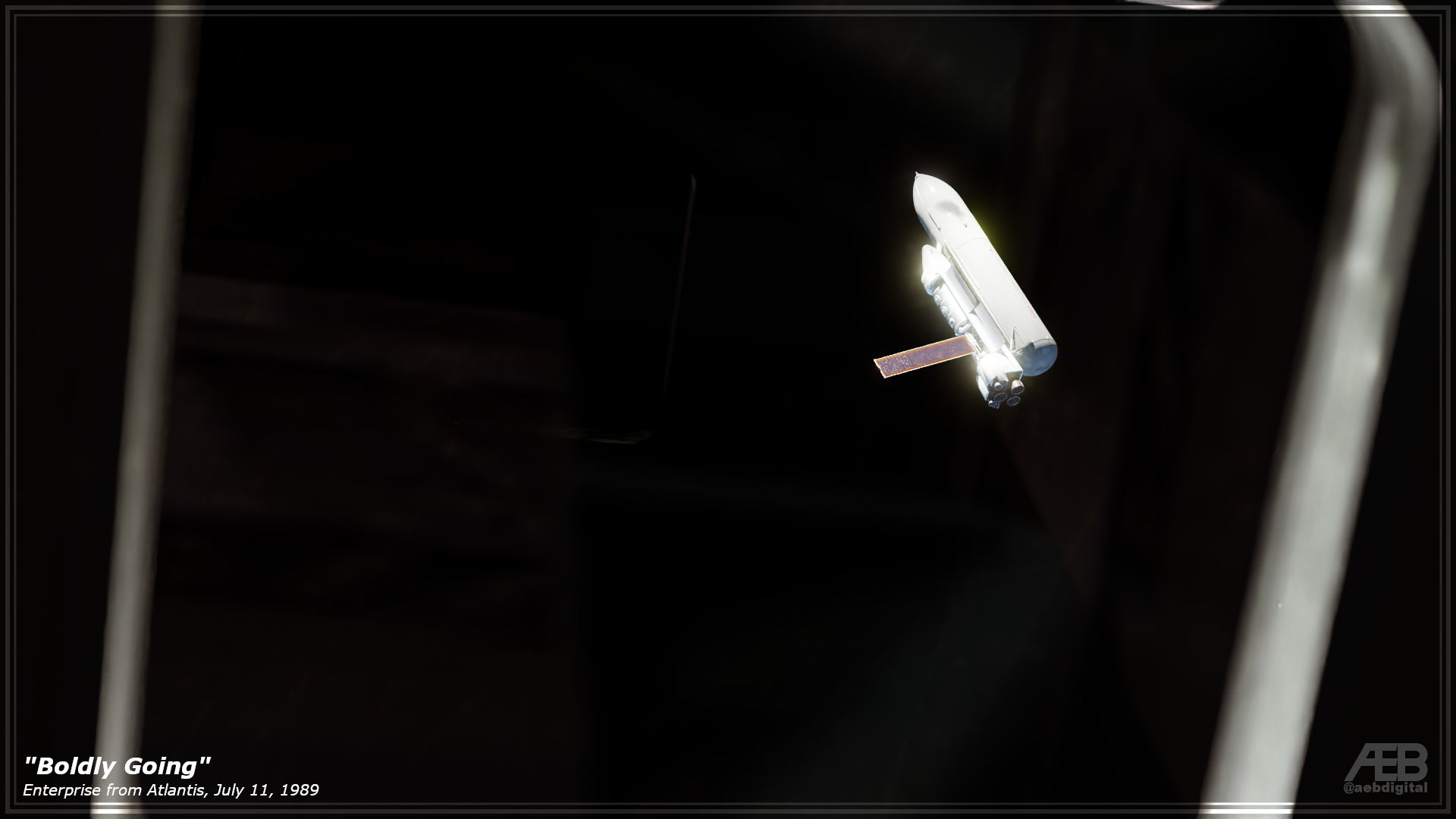

Engle and the rest of the STS-38R crew made rendezvous with

Enterprise in the station’s 39-degree, 350 km orbit on July 11, 1989. They had spent their first full day in orbit, Flight Day One, chasing down the station from their lower elliptical parking orbit. The results greeted them on Flight Day Two, July 11th as they approached their target. It was, in one sense, the first arrival of Shuttle at a space station--one of three the Space Shuttle would visit during its history. In another, it was the first rendezvous of two orbiters in space, and the first docking of the Space Shuttle to anything at all. In

Atlantis’s cockpit, what it looked like was a tremendous challenge for the flight crew. The enormous white external tank was starkly visible, and the crew called “tally ho” on the station from kilometers out. The station’s bulk grew slowly. With the distance disguised by the clarity of vacuum,

Enterprise and the external tank hung in space like a model, looking at first glance no larger than the small satellites Shuttles had deployed and retrieved in the past. It was only in the final minutes, as the distance melted away, that the true scale of the station became clear.

Artwork by:

@nixonshead (

AEB Digital on Twitter)

)

)