It's beginning. It's beginning!BANG! BANG! BANG!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Under the Spreading Chestnut Tree: A Nineteen Eighty-Four Timeline

- Thread starter Roberto El Rey

- Start date

-

- Tags

- 1984 book derivative dystopia orwell

I like the storyline so far.

One thought springs in mind: "Isn't O'Brien an unreliable narrator? Which also makes the book he gives to Winston unreliable.Therefore you have maybe more artistic freedom for your timeline than you realize."

One thought springs in mind: "Isn't O'Brien an unreliable narrator? Which also makes the book he gives to Winston unreliable.Therefore you have maybe more artistic freedom for your timeline than you realize."

I do indeed realize how much artistic freedom I have. This has spawned a multitude of interpretations of what's "real" about society in 1984 and what isn't. One of my favorite TLs on this site, Images of 1984 (which I linked to in an earlier post), posits a world in which Oceania only controls Great Britain, and Goldstein's book, at least as far as the backstory, is fabricated. The author of that one took full advantage of the freedom he had.I like the storyline so far.

One thought springs in mind: "Isn't O'Brien an unreliable narrator? Which also makes the book he gives to Winston unreliable.Therefore you have maybe more artistic freedom for your timeline than you realize."

With this, I've made a choice to take most (though not all) of Goldstein's book seriously. I am taking a bit of license with a couple of the aspects, but overall the general description of the world and history behind it in Goldstein's book is accurate.

When this timeline is finished and I post it in the finished TLs forum, I plan to write, as an introduction, a section of Goldstein's book that will go further into detail about the backstory and history of the world.

Funnily enough, the more I've thought about 1984 and the situation it is trying to mimic, the more I've bought into the theory that Oceania is just a radical pariah regime. I think it really was a stroke of genius by Orwell to make things so ambiguous you have no way of knowing for sure what's real and what's not.

Last edited:

37

The Marvelous Misadventures of Eric Blair, Part II

12 April 1933

It was a cloudy Tuesday morning, and only a little sunlight fell onto Eric Blair's desk in the Times office. Eric was in the midst of lighting an old lamp when he heard his name called from behind; he turned around to see none other than Emmanuel Goldstein, the energetic, immutable voice of Socialist Labour, heading his way. “Mr. Blair!” Goldstein called again, weaving his way through the maze of desks.

“Mr. Goldstein!” cried Eric, quite surprised at the visitor. “What a surprise to see you here,” he continued, reassuming his composed voice. “How are you today?”

“Alright, Mr. Blair, very alright,” Goldstein replied, offering Eric his hand.

“Call me Eric, please,” said Eric as they shook hands. “I don't believe we've met before. Is there anything I can do for you?” Eric had seen Goldstein before during sittings of the Commons. He was a captivating speaker from way up in the press gallery, but up close he was something different. The man radiated an aura of supreme intelligence. Goldstein was only a few years older than Eric, but his eyes alone had a sort of knowing quality about them that Eric could hardly expect to possess. In one gaze, they could read more about you than you were willing to offer up. And even in casual conversation, Goldstein always seemed to know exactly what he was going to say—and, oftentimes, exactly where you were going to say, too.

“As a matter of fact, I wanted to ask you a question,” Goldstein replied. “I've read your stuff in The Times. I've always thought it was just a bourgeois rag, but your articles give me hope for our country's standards of journalism.” At this, Eric chuckled jovially.

“I hope I'm not overstepping my bounds, but it seems to me that...” Goldstein paused, leaned in a bit and lowered his voice. “it seems to me that you're one of us, Mr. Blair.” There was a slight pause; as Eric thought up a response, Goldstein inhaled and his eyes widened imperceptibly, just enough to lose their confident stare.

Eric paused. “I never have had much regard for the capitalist class—by which I mean those people who steal from the workers all their lives, and then go about the street in top hats demanding their respect. If we have that conviction in common, Mr. Goldstein, then I suppose that I am indeed one of you.”

Goldstein's eyes reassumed their knowing gaze and his lips curled into a slight smile. “That's very good to know, Eric,” he said with a mix of expectance and relief. “In that case, I'd like you to stop by the Party office soon. Our party may not have our own newspaper, but it would quite help to have a friend in the press,” said Goldstein earnestly.

"It would be my pleasure," Blair replied. "Excellent. Can you come by this Sunday at three?" inquired Goldstein. "Most certainly," said Blair.

"Good. Sir Mosley would like to meet you. Do you know Sir Oswald Mosley?"

"I've seen him in Commons, but I've never met him personally."

"Well, you'll meet him on Sunday," said Goldstein with another comradely smile as he turned to the door. "I'll see you soon, Eric," added Goldstein as he passed through the door to brave the London streets.

12 April 1933

It was a cloudy Tuesday morning, and only a little sunlight fell onto Eric Blair's desk in the Times office. Eric was in the midst of lighting an old lamp when he heard his name called from behind; he turned around to see none other than Emmanuel Goldstein, the energetic, immutable voice of Socialist Labour, heading his way. “Mr. Blair!” Goldstein called again, weaving his way through the maze of desks.

“Mr. Goldstein!” cried Eric, quite surprised at the visitor. “What a surprise to see you here,” he continued, reassuming his composed voice. “How are you today?”

“Alright, Mr. Blair, very alright,” Goldstein replied, offering Eric his hand.

“Call me Eric, please,” said Eric as they shook hands. “I don't believe we've met before. Is there anything I can do for you?” Eric had seen Goldstein before during sittings of the Commons. He was a captivating speaker from way up in the press gallery, but up close he was something different. The man radiated an aura of supreme intelligence. Goldstein was only a few years older than Eric, but his eyes alone had a sort of knowing quality about them that Eric could hardly expect to possess. In one gaze, they could read more about you than you were willing to offer up. And even in casual conversation, Goldstein always seemed to know exactly what he was going to say—and, oftentimes, exactly where you were going to say, too.

“As a matter of fact, I wanted to ask you a question,” Goldstein replied. “I've read your stuff in The Times. I've always thought it was just a bourgeois rag, but your articles give me hope for our country's standards of journalism.” At this, Eric chuckled jovially.

“I hope I'm not overstepping my bounds, but it seems to me that...” Goldstein paused, leaned in a bit and lowered his voice. “it seems to me that you're one of us, Mr. Blair.” There was a slight pause; as Eric thought up a response, Goldstein inhaled and his eyes widened imperceptibly, just enough to lose their confident stare.

Eric paused. “I never have had much regard for the capitalist class—by which I mean those people who steal from the workers all their lives, and then go about the street in top hats demanding their respect. If we have that conviction in common, Mr. Goldstein, then I suppose that I am indeed one of you.”

Goldstein's eyes reassumed their knowing gaze and his lips curled into a slight smile. “That's very good to know, Eric,” he said with a mix of expectance and relief. “In that case, I'd like you to stop by the Party office soon. Our party may not have our own newspaper, but it would quite help to have a friend in the press,” said Goldstein earnestly.

"It would be my pleasure," Blair replied. "Excellent. Can you come by this Sunday at three?" inquired Goldstein. "Most certainly," said Blair.

"Good. Sir Mosley would like to meet you. Do you know Sir Oswald Mosley?"

"I've seen him in Commons, but I've never met him personally."

"Well, you'll meet him on Sunday," said Goldstein with another comradely smile as he turned to the door. "I'll see you soon, Eric," added Goldstein as he passed through the door to brave the London streets.

Last edited:

38

Swearing-in of President John Garner, March 4, 1933

The presidency of John Nance Garner was a disaster for America.

As President, Garner rejected Roosevelt's "New Deal" policies, instead opting to solve the economic crisis by devolving power to the states. This worked very poorly in the short and the long term. The rural areas of the south remained largely devoid of infrastructure, as no state government had enough capital to successfully fund economic initiatives. Larger states in the west didn't have the money to do anything worthwhile economically. Crime rose in cities like New York, Chicago and Pittsburgh as unemployment skyrocketed.

To deal with unemployment, more liberal governors like Hebert Lehman of New York founded state-level organizations like the New York Construction Corporation that employed hundreds of thousands of residents of their cities. However, due to lack of revenue the states mostly left the running of these organizations to the labor unions, which grew immensely in size, power and influence as a result. Several strikes were organized to protest President Garner's policies.

Other, more conservative governors like Flem Sampson in Kentucky addressed unemployment by subsidizing and privatizing the construction of infrastructure. More jobs and roads were made this way, but companies like Texaco and Chrysler were essentially given free reign to treat their workers like dirt. Dozens of riots and strikes sprang up in response.

It was in this context that the working class became an extremely potent political force. Both major parties were despised by the working class: the Democrats under Garner were doing an atrocious job running the country during this crisis, and Hoover's "rugged individualism" Republicans were still fresh in memory. This started the workers' relationship with the Socialist Party of America.Rise of the Socialist Party

Socialist Party rally, Boston, May 1st 1934

Most shockingly, the Socialists brought 90 seats to the House of Representatives and 18 seats to the Senate, splitting both houses so that no party had a strict majority. For the first time in eighty years, a third party had tangible representation in Congress, stunning Democrats and Republicans alike.

Last edited:

...wait a minute, did you delete the update before that last one or am I majorly derping up now?

...wait a minute, did you delete the update before that last one or am I majorly derping up now?

Which update do you mean? I did edit this one about Garner's presidency last night to make it a little easier to read and cover more material.

Which update do you mean? I did edit this one about Garner's presidency last night to make it a little easier to read and cover more material.

Right, right. I actually thought it was good as it was (was just expecting a new update to continue the tale), but nothing wrong with this either.

Welp, can't wait to see how hellish the 1936 presidential election will turn out.

39

Excerpt from From Jackson to Wright: The Democratic Party by Douglas Robertson (1949)

When President Garner ran essentially unopposed for the Democratic nomination in 1936, he assured himself that he still had national control of the Democratic Party. He failed to grasp that his radical policies of decentralization meant that it was no longer possible to have national control of the Democratic Party. In truth, the burgeoning Socialist Party had already stolen away most of the liberal voters, and most of the northern conservatives were rapidly diffusing to the Republicans, leaving little more than the southern conservative faction which were happy to be represented by the Texan Garner. Multiple Democratic governors were, thanks to the lack of party discipline, free to criticize Garner's policies and campaign, and many did. Some Democratic governors blatantly endorsed the Republicans or the Socialists. And as readers will likely know, one particular Democratic Senator deserted the party entirely that year to run against Garner's ticket.

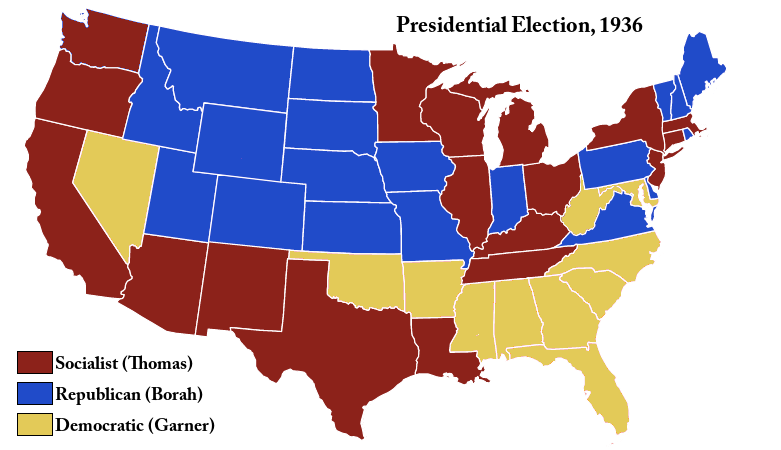

The Presidential Election of 1936

When Norman Thomas, the newly-elected Governor of New York and leader of the Socialist Party, was selected as the Socialist candidate for the election of 1936, some were surprised. He had already been the Party candidate twice in a row, but for the first time he faced major opposition in the form of Huey Long, the formerly-Democratic Senator from Louisiana. Many voters believed that, now that the Socialists had a real chance at victory, they would need a more energetic candidate to bring in the vote. Ultimately, Thomas's seniority held against Long's novelty in the Party, but he and the rest of the party were ecstatic to name Long as Thomas's running mate in the election.

Meanwhile, President Garner and Vice President Byrns won their party's nomination, while the Republicans chose William Borah as their candidate with Alf Landon as his running mate. Borah hardly tried during his campaign, as the Democrats' shattered reputation led the GOP to expect a landslide victory in the electoral college and a comfortable majority in Congress. Ultimately, he barely campaigned in key states like Ohio and Tennessee, a move which would hurt him in November.

Norman Thomas, Governor of New York and the Socialist Party Presidential Candidate, Campaigning in Houston

Huey Long, Vice Presidential Candidate for the Socialist Party, Addresses a Crowd in Oregon

Picking Huey Long to run with Thomas turned out to be a massive advantage for the Socialist Party. While Byrns and Landon, the other parties' candidates for VP, were colorless and dull, Long added a flair to the Socialist campaign that neither of the other parties could compete with. Thomas and Long played off each other well, as Thomas's rational and calm campaigning was whipped into a cacophony of emotion by Long's intensity.

As the Thomas-Long duo made their way across the country, they expanded into strongholds of conservatism never thought penetrable by Socialists, including California and Texas. The Socialist campaign in California was helped greatly by the new Socialist governor Upton Sinclair, whose first two years in office produced enough decent economic legislation to win over most Californians to the Socialist vote. Texas, meanwhile, had just elected Democratic governor James Allred. While not joining the Socialists directly, Allred proved indispensable to the Socialist campaign, openly endorsing the Thomas-Long ticket against his own Party's interests.

On November 3, 1936, the votes were counted, and they were historic:

With 281 electoral votes, the Socialists had taken the presidency. Despite only narrowly winning in key states like Texas and Kentucky, the Socialists had secured their first-ever presidential victory, achieving what would have been a crazy dream four years before. The Republicans had been roundly defeated, taking only 149 electoral votes, most of them from Indiana and Pennsylvania (which they won by much narrower margins than expected) and the rural west. The Democrats, meanwhile, were humiliated. The "Solid south" was breaking apart as five loyal Democratic states left the southern bloc, and the rest all came within fifteen percentage points of flipping. Outside of the South, only Nevada had come out for Garner. With just eleven states and 99 electoral votes, the Democrats were in third place for the first time in their existence.

The House was 222 Socialist, 152 Republicans and 51 Democrats; a thin majority, but a majority nevertheless. The Senate was less ideal: it held 46 Socialists, 33 Republicans and 15 Democrats. The Socialists were just a hair shy of an outright majority, but Farmer-Laborite Ernest Lundeen and Progressive Robert La Follette Jr. had both managed to hold on to their seats from Minnesota and Wisconsin. That was excellent news for the Socialists--both were almost certain to vote with them on every issue, which would bring the tally up to 48--a perfect 50% of the 96-seat Senate. There were several progressive Senators in the other two parties who could easily be persuaded on key issues, and there was always Vice President Long to break ties. As President Thomas entered the Oval Office for the first time, he felt the optimistic expectations of a productive term of office.

On March 4, 1837, the first Democratic president had left the White House. Today, one hundred years to the date, the last Democratic president would be leaving office.

When President Garner ran essentially unopposed for the Democratic nomination in 1936, he assured himself that he still had national control of the Democratic Party. He failed to grasp that his radical policies of decentralization meant that it was no longer possible to have national control of the Democratic Party. In truth, the burgeoning Socialist Party had already stolen away most of the liberal voters, and most of the northern conservatives were rapidly diffusing to the Republicans, leaving little more than the southern conservative faction which were happy to be represented by the Texan Garner. Multiple Democratic governors were, thanks to the lack of party discipline, free to criticize Garner's policies and campaign, and many did. Some Democratic governors blatantly endorsed the Republicans or the Socialists. And as readers will likely know, one particular Democratic Senator deserted the party entirely that year to run against Garner's ticket.

The Presidential Election of 1936

When Norman Thomas, the newly-elected Governor of New York and leader of the Socialist Party, was selected as the Socialist candidate for the election of 1936, some were surprised. He had already been the Party candidate twice in a row, but for the first time he faced major opposition in the form of Huey Long, the formerly-Democratic Senator from Louisiana. Many voters believed that, now that the Socialists had a real chance at victory, they would need a more energetic candidate to bring in the vote. Ultimately, Thomas's seniority held against Long's novelty in the Party, but he and the rest of the party were ecstatic to name Long as Thomas's running mate in the election.

Meanwhile, President Garner and Vice President Byrns won their party's nomination, while the Republicans chose William Borah as their candidate with Alf Landon as his running mate. Borah hardly tried during his campaign, as the Democrats' shattered reputation led the GOP to expect a landslide victory in the electoral college and a comfortable majority in Congress. Ultimately, he barely campaigned in key states like Ohio and Tennessee, a move which would hurt him in November.

Norman Thomas, Governor of New York and the Socialist Party Presidential Candidate, Campaigning in Houston

Huey Long, Vice Presidential Candidate for the Socialist Party, Addresses a Crowd in Oregon

As the Thomas-Long duo made their way across the country, they expanded into strongholds of conservatism never thought penetrable by Socialists, including California and Texas. The Socialist campaign in California was helped greatly by the new Socialist governor Upton Sinclair, whose first two years in office produced enough decent economic legislation to win over most Californians to the Socialist vote. Texas, meanwhile, had just elected Democratic governor James Allred. While not joining the Socialists directly, Allred proved indispensable to the Socialist campaign, openly endorsing the Thomas-Long ticket against his own Party's interests.

On November 3, 1936, the votes were counted, and they were historic:

With 281 electoral votes, the Socialists had taken the presidency. Despite only narrowly winning in key states like Texas and Kentucky, the Socialists had secured their first-ever presidential victory, achieving what would have been a crazy dream four years before. The Republicans had been roundly defeated, taking only 149 electoral votes, most of them from Indiana and Pennsylvania (which they won by much narrower margins than expected) and the rural west. The Democrats, meanwhile, were humiliated. The "Solid south" was breaking apart as five loyal Democratic states left the southern bloc, and the rest all came within fifteen percentage points of flipping. Outside of the South, only Nevada had come out for Garner. With just eleven states and 99 electoral votes, the Democrats were in third place for the first time in their existence.

The House was 222 Socialist, 152 Republicans and 51 Democrats; a thin majority, but a majority nevertheless. The Senate was less ideal: it held 46 Socialists, 33 Republicans and 15 Democrats. The Socialists were just a hair shy of an outright majority, but Farmer-Laborite Ernest Lundeen and Progressive Robert La Follette Jr. had both managed to hold on to their seats from Minnesota and Wisconsin. That was excellent news for the Socialists--both were almost certain to vote with them on every issue, which would bring the tally up to 48--a perfect 50% of the 96-seat Senate. There were several progressive Senators in the other two parties who could easily be persuaded on key issues, and there was always Vice President Long to break ties. As President Thomas entered the Oval Office for the first time, he felt the optimistic expectations of a productive term of office.

On March 4, 1837, the first Democratic president had left the White House. Today, one hundred years to the date, the last Democratic president would be leaving office.

Last edited:

Who is this Wright guy?From Jackson to Wright: The Democratic Party by Douglas Robertson (1949)

Last edited:

I hope to see when the butterfly hit far eastern asia..

Keep in mind, President Thomas and his party are pacifists. He and the Socialist-controlled Congress won't mount much of an opposition to the Japanese as they expand across the Pacific.

Doublethink hasn't really made its grand entrance yet. A few other conventions of 1984, like the falsification of past records and military-first policies, have already been shown to a degree, and will grow in significance and obviousness as the story goes on. There have been a few subtle instances of doublethink, such as when the eyewitness recounting the November Putsch says that he "didn't want to do anyone a bit of harm", and then in the same paragraph says that he "had to fight the urge to pick up a gun and pick 'em off one by one, those miserable bastards".Where was doublethink mentioned ITTL?

Doublethink will develop independently in all of the three major superpowers. It will really come into its own in the forties, fifties and sixties, as political observers will notice that the main source of dissent is always the inner thoughts of subjects. The next post (which is taking longer than normal because of my rather busy schedule last week) will show the first seeds of Ingsoc being planted, and will make clear the contradictions that define it from the very beginning.

This TL has been really fun! I love your writing style, it always grabs me.

I'm very curious on how the socialist labor party will transform into Ingsoc.

I'm very curious on how the socialist labor party will transform into Ingsoc.

Last edited:

You'll get a better idea with the next update. (Sorry that's taking so long. My work schedule was quite full this last week and I've had just about zero time to actually write out the entries. Instead, I've been going over every detail in my head instead of actually doing workI'm very curious on how the socialist labor party will transform into Ingsoc.

Share: