Alright, let's get the train going again. This one is by far one of the largest (if not

the largest) chapters I've written for the TL. At first I intended to break it up, but then, I figured it was worth of being posted whole, because there is but a single narrative theme in all the following subchapters.

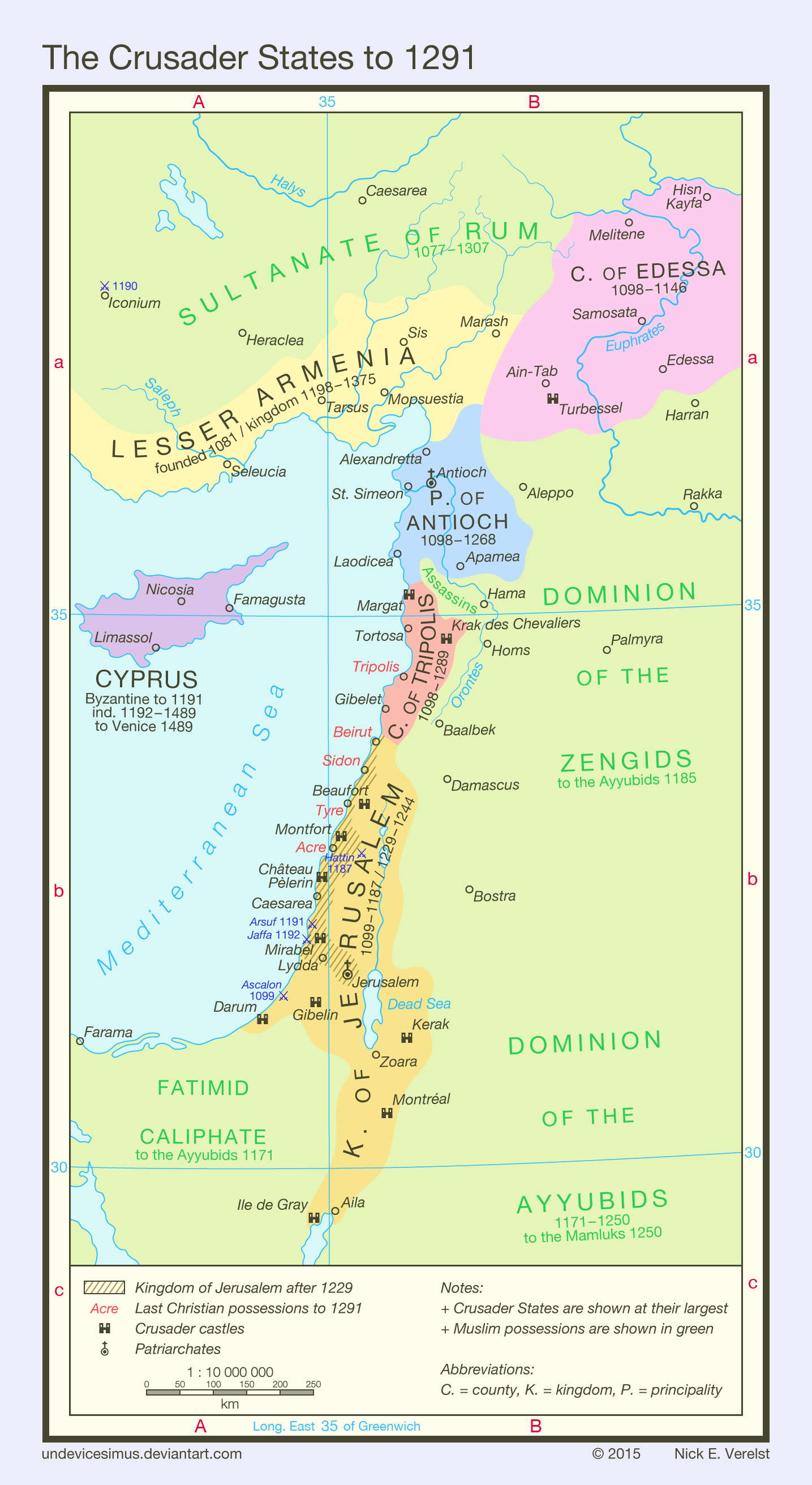

THE SECOND WAR BETWEEN THE CRUSADERS (1168 - 1173 A.D.)

Illumination in the Cronica Hierosolimitana depicting the Battle of Saflat [Safed]

Raymond-Jordan is Nominated Prince of Jerusalem and Duke of Galilee

Now, we ought to reminisce that, in 1168 A.D., in the shores of

Lake Möeris, called Qarun or Karun in the tongue of the Saracens,

Raymond, second of this name of the Princes of Jerusalem, gave battle to the infidels and there he perished. In that day, many other lords and knights of the Outremer were ignominiously slain after being deprived of their armament and armor, such as Eustace of Tiberias and Alexander of Tripoli, as well as some of the clergy, such as Bishop Hugh of Haifa. All of them would be recognized as martyrs of the Christian faith by

Pope *Lucius III.

The news about the death of the Prince swiftly came to the Templarians in Jerusalem, and they immediately gave notice to Archbishop Bernard, who, having ventured into Egypt in the very first year of the war, had since then remained in the Outremer, to perform his various administrative, ecclesiastical and judicial duties, trusting the practice of war to the equestrian nobles. Now, he knew, the untimely death of these warriors was to have serious consequences for the Crusader State.

Tancred of Damascus and other Norman and Lombard nobles affiliated to him had remained in Damietta after Raymond marched in his doomed expedition to take Cairo. Likely out of fear of treachery from Tancred, who was a detested enemy, Raymond did not deign to summon him to the incursion into the Nile River, so that he would not have to share the spoils of the triumph that, ultimately, never happened. Even after the battle of Lake Möeris, Tancred and his sergeants stayed in Damietta. He and his soldiers would later participate in the hopeless defense of this metropolis against the

Fāṭimīds and the

Almohads.

As it happened, then, the Archbishop of the Holy Land, in the beginning of 1169 A.D., saw fit to nominate Raymond’s son, also named

Raymond [III], known as “

the Thrice-Christened”, as the new Prince of Jerusalem and Duke of Galilee, and he thus became the third of this name in the temporal rulership of the Outremer.

Though the laws of the Earthly Kingdom had yet to be codified, and there was no Papal-sanctioned rule provisioning for the election of the Princes of Jerusalem, his measure incurred in the dissatisfaction of the lay aristocracy, seeing it had already become an established custom for at least four generations, ever since the First Crusade. Of course, they preferred a genuine elective system, in which they were equals and by the terms of which any of them - at least those who held the vote, influence and prestige - could be selected to be the first among them.

Bernard was no fool, and predicted the nobles might oppose his abrupt intervention in the selection procedure of the lay prince. As a countermeasure, he solicited, in 1168 A.D. from Pope Lucius a

proclamatio confirming his own supreme authority as the Papal legate active in the Holy Land, and institutional powers to nominate and depose the lay prince by his own volition. Indeed, according to the Pope’s own words, in his capacity as “Apostolic Legate”, the Archbishop of the Holy Land ought to receive divine inspiration to choose the defender of the Holy Sepulcher from among the most virtuous and pious of the Crusader knights, and to grant him the banner of the True Cross.

In spite of this formal sanction of Pontifical legitimacy, the Frankish grandees knew all too well that Bernard, an ambitious and worldly character, had his own agenda, one that sought to establish the spiritual authority as being superior to the temporal one. This Bernard exemplified by ordering the minting of coins with the effigy of the Pope (of whom he himself was a direct political representative), instead of using the traditional and more conservative abstract images representing the cross on one side and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, which were symbols of Jerusalem proper.

The nobles knew, too, that Raymond-Jordan could be a convenient instrument to Bernard's desideratum. At the time of his accession to the Princely throne, he did not have much to show for. Aged twenty one years old, he was young and had little experience in matters of war or of the administration of the state, while most of his predecessors, such as his own father, were older or at least seasoned in the battlefield. His depiction by contemporary troubadours, as the perfect model of a chivalrous knight: valiant, gallant, god-fearing and generous, is all too suspect, especially considering that his family consistently bestowed patronage to them. However, it might be more fitting with reality the much less acclamatory portrayal of

Ralph of Coggeshall - the English monk who became Metropolitan Bishop of Damascus at invitation of Countess Mabel -, in his “

Chronicon Terrae Sanctae”, describing Raymond-Jordan as timid and mercurial personage, who seemingly had little desire to actually rule.

In any case, whatever resentment the lay nobles might have towards Bernard and Raymond-Jordan was not demonstrated at the time. On the contrary, all of them attended a gathering presided by Raymond-Jordan in Nablus, in the spring of 1169 A.D., with the intent of mustering another army to relieve Frankish-controlled Damietta. The new Prince, however, was eventually forced to turn to the Michaelites and to the Hospitallarians for reinforcements and material assistance, considering that the war in Egypt had consumed a substantial portion of the Frankish manpower, mostly from disease and attrition during the various sieges, but also from his father’s last stand in the desert.

Before the Franks could even arrive in Egypt, however, they received grim news: Damietta had fallen to an allied army of “Saracens and Moors” (i.e. the Almohads), and, after being expelled from it, thousands of Christians, notably Franks and Armenians, were mercilessly slain, including Tancred of Damascus. The cruel barbarians did not deign to give them proper burials, and thus their corpses were left to jackals and vultures, and their skeletons became interred in the sands in the fringe of the Sinai desert.

Raymond then returned to Palestine, and granted the control of the castles of the Sinai and of southern Palestine, which pertained to his own personal demesne, to the Templarians, so as to protect the southwestern border of the Earthly Kingdom against a possible assault from the Egyptians.

Bohemond II returns to the Outremer

In 1169 A.D., to the great astonishment of Raymond and Bernard,

Bohemond (II) Red-Face, the dispossessed ruler of Tyre, disembarked in that city, together with a small army of Sicilians and Lombards commanded by

Simon of Taranto, and reclaimed his titles and estates. It is probable that Bohemond did know that Raymond II had been slain in Egypt in the previous year, and now sought to capitalize in the inevitable competition for succession. The Sicilian intervention in the Outremer, in support of Bohemond, must be situated in the larger context of the war between Sicily and Rhõmanía, likely devised by the Prince in Palermo to create a diversion and open another front of war against the Rhõmaîoi. We do not know about the conditions of the alliance of Bohemond and Prince William III of Sicily; no source suggests that Bohemond accepted vassalage to William, nor that the latter regarded him as anything but an equal. On the other hand, it seems that Simon of Taranto and his men were hired by Bohemond as mercenaries, thus forming one of the first companies of this kind. William of Sicily liked expected, in the event that Bohemond achieved mastery over the Outremer, to share whatever economic rewards he might obtain, while Simon’s soldiers expected immediate payment.

Even if Bohemond, at first, presented himself merely as an wronged nobleman, who sought to reclaim his birthrights in Tyre against the tyrannical acts of an unjust suzerain (Bernard, in this case), it became all too clear from the start that Bohemond desired to depose Raymond, and place himself as the ruling Prince of Jerusalem, as well as to force the Archbishop of Jerusalem into political submission.

Bernard, shocked by Bohemond’s sudden appearance, convened the Court of Grandees and proclaimed that, since Bohemond had been banished from the realm and stripped of his honors and patrimony, his unauthorized return made him liable to the pain of death. He thus summoned the vassals of the realm to subdue this Norman aristocrat that he deemed a “wretched criminal”.

Bohemond, however, was held in great regard by the Normans and Lombards of Phoenicia and also by the Maronites, to whom he had pledged many benefits during his early years, and they mustered to him, seeing that his sentence had been unjust and unworthy of his valor and his position. Now he had another formidable ally, this being

Richard, Lord of Arca [

Arqa], brother of the deceased Count Alexander of Tripoli, and who claimed his inheritance. Alexander, after perishing in Egypt, was nominally succeeded by his son William (III), who, however, was still a minor, and had his accession challenged by Richard. The latter proclaimed allegiance to Bohemond while William was supported by Bernard and Raymond.

Now, Bohemond, sided by Richard of Arca and other minor nobles of both Syrias, pleaded to the Court of Grandees for an election so that the Prince of Jerusalem and Duke of Galilee could be chosen by his peers. It is likely that was all but a ruse to gain time, because Bohemond immediately assembled the men-at-arms at his disposal and his allies, and, joined by the Sicilians, marched on Jerusalem. At the time, Raymond was in Caesarea, and thus, when the Normans arrived in the Holy City, Bernard was bereft of soldiers, the defense of his capital attributed to only the urban guardsmen and the knights of the military fraternities. The latter, however, having their manpower reduced by the Egyptian war, and by the necessity of maintaining the border fortresses, were in few numbers in Jerusalem. The Archbishop nonetheless refused to admit Bohemond’s entrance, accusing him of sedition and even of heresy and the situation rapidly escalated. The Count of Tyre, incensed by the debacle, initiated siege operations after the Templarian sworn-brothers charged against his men, being repelled only after a fierce melee. Bohemond knew, however, that triumph could only be certain if the Archbishop capitulated and accepted his conditions.

Raymond, having hastily mustered an army of Frankish knights, Palestinian levies and Genoese mercenaries, attempted to surprise the Normans by attacking them from the rear, but failed to do so and was repelled in a brief engagement. Bohemond, however, could not besiege Jerusalem with the forces he was commanding, and, indeed, it seems that the very thought of shedding blood in the Holy City appalled him, so he raised the camp and returned to Tyre, so as to await for the arrival of Richard with reinforcements. He did arrive a few days later, bolstering the Norman, Lombard and Sicilian army, and thence they marched against the territories that belonged to the Prince of Jerusalem, regarded as nothing more than a pawn of the devious Archbishop.

It was good news to Bohemond, then, that

Mabel, the dowager Countess of Damascus, joined his cause and demanded an election to choose another Prince of Jerusalem and Duke of Galilee by the body of grandees.

It is worth noting that neither she nor Bohemond or any of his partisans saw it too wise to directly challenge the Papal

proclamatio, perhaps wary of being accused of religious schism. In fact, they acknowledged its terms, but instead challenged the premise that Raymond was indeed the “most virtuous and pious” of the Crusader knights, and argued that he was untested in battle and held no virtues whatsoever. Needless to say, it was a poor argument, and it scantily contradicted Bernard’s accusations of

lèse-majesté against the Pope, but, in the end of the day, might still made right in the Frankish Orient, and Tyre and Damascus hoped that, in the event of a military defeat, Bernard would be forced to acquiesce Bohemond’s claim anyway, or would be forcefully removed from power.

While she ruled nominally as a regent to her child son, Roger II of Damascus, Mabel was a fierce fighter and a proud descendant of William the Conqueror, who dressed in armor and led men in the field of battle, and thus her support was very much welcomed by Bohemond. According to Ralph of Coggeshall, a young English monk who had come as a pilgrim to the Holy Land and was created Metropolitan Bishop of Damascus - and who wrote one of the principal sources of the period, having been an eyewitness of many of its events -, she intended to avenge perceived humiliations against her family attributed to the dynasty of Toulouse.

Raymond, believing himself to be outnumbered, retreated to Caesarea without giving battle to Bohemond and Richard, so as to await for his own allies to succor him. Meanwhile, Mabel hastily assembled her retainers, vassals and levies in Damascus.

Raymond’s cousin

Godfrey of Tiberias had only been recently elevated to the comital throne in Tiberias, after his brother Eustace died in Egypt, but he had proved his valor in the war against the Saracens in Egypt, and was also quick to assist Raymond with the host of Tiberias. In an engagement near Acre, he successfully thwarted Bohemond’s advance along the Mediterranean littoral, but Raymond arrived too late with his own men to assist Tiberias, and this allowed the Normans to retreat in good order. Then, the Prince refused to undertake pursuit, preferring to await the arrival of the Marquis of Tortosa.

His indecisiveness, however, gave Mabel the time she needed to assemble her own levies, and, in the beginning of the following month, she fell upon Godfrey’s lands north of Lake Tiberias, and put the fort of

Saflat [Isr.

Safed] to siege. She found the stronghold undermanned, with many of its soldiers having joined Godfrey’s field army. It is said that she, cleverly taking advantage of the manly vices, employed various prostitutes to seduce the soldiers there standing, mostly of Palestinian and Armenian stock, and convinced them to abandon their posts, in exchange for a night of drunkenness and debauchery. In the dark of night, the gates were opened and the Damascene soldiers entered and put the stupefied defenders to death, some of them still embraced by the treacherous seductresses, who supposedly relished in the grisly outcome. Afterwards, Saflat was to be used as an advanced base of operations for Bohemond and Mabel.

*******

After taking Saflat, the Normans attempted to force Raymond into battle when he was afield, but, when the Prince refused, opting to retreat once again, the Damascenes launched various raids to ravage Lower Galilee. In retaliation, the Toulousains raided the Syrian communities south of Tyre.

In spite of the fact that Raymond preferred to avoid direct confrontation, instead opting to sustain a war of attrition against the Normans, especially against the

demesne of Tyre, Bernard demanded immediate action against Bohemond. He himself donned his armor and mace, and assembled the Templarians in arms, and then marched directly against Saflat, urging Raymond and Godfrey to join him. Even if the Templarian sworn brothers had no particular love towards Bernard, they respected his authority as the Apostolic Legate, and gave almost fanatical devotion to the Papacy, especially to the memory of Pope Stephen X, who had been their greatest benefactor. The Knights of Saint Michael, however, refused to raise arms against fellow Christians, condemning the bloodshed, and argued that they ought to join together against the infidels, but to this Bernard responded with hostile threats, proclaiming that those inimical to the Earthly Kingdom were no better than heretics. It must be mentioned that dynastic and cultural affinities might have mattered in this specific case, unlike that of the Templarians - because the current

Grandmaster of the Michaelites,

Otto Gastald [It.

Oddone Castaldo] was a Lombard nobleman whose family was related by marriage to the House of Salerno - but the whole debacle provoked the discontentment of the monastic orders, namely the Michaelites and the Cenaculiarians, whose masters exhorted Bernard to attempt a peaceful solution. The Archbishop, however, would have none of it, and refused any sort of settlement.

Godfrey and Raymond followed Bernard, the former eager for battle, and the latter much more reluctant. Their enemies incited the Archiepiscopalian army to assault their fortified positions, but then they found that Bohemond’s army had established an improvised camp near the fortress of Saflat, which itself was situated atop a mountain, garrisoned by the Damascene heavy infantry and archers. Thus, the Jerusalemite army had to either divide its forces to attack both of these fortified positions, or to concentrate against one of the targets, and thus open themselves to flanking maneuvers from the other one.

Firstly, Bernard attempted to attack Bohemond’s army in ground level, believing it to be an easier target, but they were repelled with substantial losses due to the concerted attack of Amalfitan and Sicilian mercenaries that had come with him to the Outremer. Employing many hundreds of crossbows - weapons of war whose usage had been banned by the Papacy decades before -, they exsanguinated the skirmishers and light infantry of Syrians and Palestinians conscripted by Caesarea and Tiberias. Afterwards, Bohemond’s seasoned warriors, who had themselves served as mercenaries in Africa and in Italy, sustained a bloody melee against Bernard’s troops, who, demoralized and struggling with inarticulate leadership, almost collapsed in a general rout. The day was saved by the Templarians, whose

Grandmaster Gerard of Aigremont charged against Bohemond’s own position and unhorsed five of his sergeants, thus allowing for Raymond and Godfrey to sound retreat.

Secondly, they attempted to reduce the fortress of Saflat, but the effort was doomed. The stronghold resisted various attempts of the assailants of storming its bastions and curtains, and, after they resigned to encircle it to await for the besieged to starve, attrition among the besiegers increased, especially because Bohemond constantly harassed them. Sapping operations against Saflat were fruitless due to the rugged terrain, and the employment of battering rams or towers was impossible, because there was but a single narrow road allowing access from the feet of the mountain to the castle.

The situation transitioned into a stalemate, because the attackers failed to either dislodge Bohemond or to capture Saflat, but, then, they had also thwarted the Normans from advancing into lower Galilee, notwithstanding constant desertion and abounding attrition by camp fever. The war then became one of maneuvers, with the forces of both sides mostly balanced in terms of manpower and available resources.

With the coming of winter, the parties agreed to an armistice, and disbanded parts of their levies, but the Normans refused to surrender Saflat, and thus, hostilities were expected to resume with the advent of spring in early 1170 A.D.

Bohemond, however, had no intention of staying idle during the truce.

He did not take further action in Palestine, but then, in the height of winter, he, with the Sicilian mercenaries, advanced against Tripoli, and, joined by Richard of Arca, they successfully deposed the infant ruler, his nephew

William, who was ignominiously imprisoned, and ransacked the Tripolitanian treasure. His retainers, receiving hefty payments, then defected to Richard and to Bohemond.

As it happened, the ruler of

Beirut, also named

William, the incumbent

Seneschal of Jerusalem, opted to celebrate a separate peace with Bohemond and Richard, considering that his own fief was situated just between theirs, and rightly feared their might; he lacked enough men or resources to resist a siege, so, preserving neutrality was not a convenience, but a necessity. Even then, he provided constant overtures to Bernard to protect himself against retaliation, and even to the Pope, to whom he sent his wife,

Joan of Albret [Occ.

Jeanne d’Albret] as an emissary to plead his intervention to cease the bloodshed in the Outremer.

To his felicity, Pope Lucius III would indeed give him ears, and would in time assemble a committee to assess the situation in Jerusalem.

******

The aggression against Tripoli violated the established peace and overturned the political and military balance of power between the belligerents, but the conflict was indeed only resumed in the following spring.

Bernard and the Provençal and Lorrainer lords once again invested against Saflat, seeing that it was too near Tiberias for comfort; if Tiberias itself fell, the whole of Palestine would be open to their enemies. They were reinforced by Saracens [i.e. Arab] conscripts levied from Transjordania and also Armenian mercenaries from northern Syria.

This time, they found Bohemond alone with his own army. It seemed that neither Mabel nor Richard had joined him. It was but a ruse. While the field army of Jerusalem was committed to the siege of Saflat, the army of Tripoli and of Damascus traversed Syria southward flanking the Anti-Lebanon mountains, and then entered the Jordan valley skirting the eastern shore of Sea of Galilee. They then crossed the Jordan river near Bassania [Isr.

Beit She’an], and spread their parties of war into lower Galilee and in Samaria, with the intent of devastating the agricultural backbone of Palestine. Only Nazareth was spared, because of its religious significance, as well as Nablus, because it was strongly fortified, but the various villages and parishes in the region were depopulated and incinerated. This forced Raymond to return in a hurry with his army to protect his lands in Samaria, and Jerusalem herself. His recklessness, however, put himself in harm’s way; in an engagement near Nablus, he successfully thwarted an assault against Caesarea, but was almost slain in the field of battle, and his men became demoralized.

In retaliation, Raymond ordered his younger brother,

William-Berengar [Occ.

Guilhèm-Berenguer],

Viscount of Acre, to conduct a seaborne assault against Tyre. Caesarea had a small fleet of half a dozen galleys, but he had contracted a group of Genoese mercenaries, who arrived in the Outremer in May 1170 A.D., and thence they raided along the Phoenician coast, focusing in Tyre and in Tripoli. William-Berengar disembarked in Tortosa, and from there, finally reinforced by the troops of his uncle,

Henry the Constable, they marched against Tripoli. The city was a formidable stronghold, and resisted siege, but the outlying country was devastated. The coastal town of

Calemont [Leb. Al-Qalamoun], which had been colonized by Beneventan Lombards, was completely destroyed, and its denizens were slaughtered, regardless of them being fellow Christians.

Once again, however, in spite of these bold advances, no side obtained a genuine breakthrough. The environmental devastation and the human casualties were significant, and so was the disruption of commerce resultant from the state of warfare, but the core centers of power in Caesarea, Jerusalem, Tiberias and Tortosa, in one side, and Tyre, Tripoli and Damascus, in the other, remained intact, and most of the castles erected in Palestine and Syria did not change hands. Transjordania, the Damascanese, Beirut and Émèse remained untouched by war.

The Coming of the Embassy from the Holy See and of Pilgrims of England and France

In late 1170 A.D., an embassy of Cardinal-Bishops and Archdeacons came from Rome to assess the situation, at behest of Count William of Beirut, and the arrival of these Pontifical dignitaries imbued with the Papal

auctoritas was enough to impose a (undesired) truce between the belligerents. Evidently, it was of great concern to the Holy See the fact that the Earthly Kingdom of God itself was suffering with what they regarded as yet another instance of knightly violence, and, their mission was to bring peace to the Realm.

Their leader was the Papal chamberlain [Ita.

camerlengo], Cardinal-Bishop

John of Naples [Ita.

Giovanni da Napoli]. The situation of the conflict was appalling, as was the loss of human lives. It was, then, somewhat surprising that the most vocal opponent of a definitive settlement was none other than the Archbishop of the Holy Land himself, Bernard, who insistently affirmed that the Count of Tyre had previously been judged for previous offenses and that his sentence had been ultimate, and that he, now, was but a criminal and offender to the divine order in the Realm of God, as were his associates. It seems that they soon enough realized, with appropriate disquiet, that Bernard had been one of the instigators of the conflict, and then sought to curb his institutional influence in the procurement of a solution to the debacle.

John of Naples was of a more pragmatic demeanor; he saw it was necessary to promote conciliation and understanding between the belligerent parties, not in the least because the Realm needed the valor and fortitude of these knights in their war against the infidels. Thus, when Bernard attempted to summon, once again, the High Court of Jerusalem to pass trial to Bohemond, he was rebuked by Papal chamberlain, who arrogated himself with higher authority in the solution of disputes.

John’s very first act was to summon the leaders of these parties to a summit in Jerusalem. There, he severely chastised them for these unlawful acts of fraternal violence, scantily a few years after many of the flock of God had perished in the dreaded land of Egypt. Then, in a symbolic act inviting penitence, they were prevented from entering the Temple and the Sepulcher, and ordered to atone for their sins. After they did, they received an also symbolic embrace into the Church, and then the

Treuga Dei [truce of God] was finally established, under promise of future adjudication of the respective claims in a new Pontifical trial. Accordingly, Bohemond, Mabel, Raymond, Godfrey and the associated princes deposed arms, and awaited for the formation of the grand trial. It was all convenient that autumn was under way and winter was coming, and keeping the levies mustered was exacting its toll on the prosperity and well-being of their lands.

The problem, however, was that John of Naples saw this act of reconciliation as enough in itself for the time being, and, instead of immediately undertaking the inquest, he decided the opportunity was good enough to install a synod to address various other questions, mostly of ecclesiastical nature. This can be understood in its historical context; under the pontificates of Stephen X and his more conservative successors such as Lucius III and Sylvester IV, there was a great concern with clerical discipline, doctrinal fundamentalism and with the institutional health of the Church-maintained organizations, such as the parishes, the monasteries and the armed fraternities. Having received various reports of dissoluteness and indiscipline of the Outremerine clergy, as well as of preoccupying denounces of simony related to the sales of supposedly holy relics, the Holy See had entrusted Chamberlain John with the task of correcting these transgressions and restoring moral purity among the men and women of God in the Holy Land. It is noticeable, from the wording of the contemporary documents, that as early as 1170 A.D. we see some prejudice from European prelates, such as John of Naples himself, against the native “

Poulain” clergymen, of which Bernard was the most notable example, who are seen as more susceptible to the vices of concupiscence and of venality due to their contact with the Syrian races, an odd animosity that is almost certainly grounded in the historical contemptuousness of the Orient as a degraded and decadent reality.

This apparent disinterest in the more pressing matter of the political dispute between the lay princes aroused the irritation of the involved nobles. In this case, the fact that the Church was seemingly interfering in a temporal matter was irrelevant; men such as Raymond and Bohemond were all too pragmatic, and were more concerned about having their conflict solved by a legitimate authority, be it spiritual or temporal.

They would have to wait, however.

******

In the same year of 1170 A.D., the Outremer saw the coming of an entourage of notables, lay and ecclesiastical noblemen from France and England. It might not have amounted to anything more than some a few hundreds, comprising the feudatories and the churchmen, and their respective retainers and assistants. Among them, must be mentioned

Robert Capet, Count of Dreux, brother to

King *Phillip II of France, who was also, by right of conquest,

Duke of Émèse [Homs]; as well as his brothers

Henry, Bishop of Beauvais, and

Peter of Courtenay, and their friends and associates,

Rotrou IV of Perche and

Henry I of Champagne, who were two of King Phillip’s most loyal vassals. Also noteworthy was the presence of

Henry of Winchester, youngest son of

King *William III of England, and his cousin

Eustace IV of Boulogne, as well as

John of Ponthieu, heir-apparent of the County of Alençon, and

Joscelin, Bishop of Salisbury.

Their voyage was part of a “

Peregrinatio Pacifica” sanctioned by *Pope Lucius III at behest of

Thomas Becket and of

Louis Capet, who were, respectively, the Archbishops of Canterbury and of Archbishop of Rheims, so as to expiate the sins committed by these nobles, all of whom had been involved in the war between the feudatories of Perche and Alençon (1166-1169), a bloody conflict which had been instigated by King Phillip II against William III of England. Although the expedition is referred as a Crusade in the contemporary English sources, it does seem that, in reality, it was all but a large-scale pilgrimage of warriors orchestrated to solve a political and military conflict between the monarchs of France and England. None of them seemed actually interested in undertaking a long-lasting campaign in the Holy Land, excepting for Peter of Courtenay, who would soon join the Templarian Order as a “lay brother”. The stories about massacre of the Frankish Crusaders after the fall of Damietta, once

Phillip of Flanders and his veterans returned to their homeland and spread the tales about the deeds and the misfortunes of the Franks in Egypt, certainly produced outcry back in Europe, but it also served to discourage any ideas of another campaign against the Fāṭimīds so soon.

They followed the

Via Francigena from northern France to Rome, whereupon they were received, as pilgrims and penitents, by Pope Lucius, and from there they went to Capua, whereupon they embarked in four Amalfitan galleys financed by them with silver borrowed from the Templarians.

The majority of them stayed in the Outremer for only a brief period, in some cases for scantily less than a month. They did entertain some ideas to campaign in Egypt, but the idea was not welcomed by Cardinal John, who instead gave them indulgences as soon as they finished the usual sight-seeing itinerary comprising the holy sites in Jerusalem, in the Jordan valley, in Nazareth and Bethlehem. The English and the Normans also had a predilection towards Lydda in Samaria, the birthplace of Saint George (regarded by them as the very first Crusader). It was this novelty that inspired one of theirs,

Ralph de Warenne, the youngest son of

William II, Earl of Surrey, to accept the offer of a money-fief associated with the town of Lydda and some neighboring villages in southern Samaria, and then he proclaimed allegiance to the Holy City and fealty to the Holy Father. Soon afterwards, he would marry Mabel of Damascus - who, like himself, was an Anglo-Norman aristocrat -, thus becoming rising from a destitute noble to one of the most prosperous lords of the Outremer.

By the time that the participants of this pilgrimage were ready to return to Europe, Robert of Dreux, with his brothers and their respective employees and servants traveled instead to Émèse, whereupon they were received with honors by

Simon [III] of Montfort, Count of Ioannine [Syr.

Salamiya] and

Gravanssour [Syr.

al-Qusayr].

The former lords of Montfort, after their predecessor Amaury came with King Phillip during the *Second Crusade and decided to start his life anew in the Orient, had become one of the wealthiest families of the Outremer, and their position as regents of Émèse over the course of the three decade-long absence of their liege-lord had allowed them to freely exploit the land to their benefit. Simon had ruled Émèse with iron fist, and, under his purview, the country had been greatly fortified by new castles, a cathedral had been constructed in the capital city, and taxes from the peasantry and the merchants were levied regularly.

Then, it came to pass that Robert, Lord of Dreux, decided that he would prolong his stay in the Outremer, so as to survey the realm that had been carved to himself during the *Second Crusade, almost thirty years before. Ralph of Coggeshall affirms that Robert was greatly impressed by the wealth and exuberance of this land of Syria, where olives, oranges, sugar beets and cotton grew abundantly from the earth, and spices from India and Cathay could be found in most markets. It is said that, after participating in a procession conducted by the Archbishop of Émèse, he vowed to dedicate himself, once again, to the cause of the cross to protect and guard the Holy Land.

His decision to remain would forever change the history of the Crusader State.

The first Synod of Jerusalem

As described in aforewritten lines, Chamberlain John of Naples installed an ecumenical synod in Jerusalem. The proceedings were held over various months from late 1170 A.D. well into the spring of 1171 A.D., when the council was finally dissolved and the Papal embassy left the Outremer.

Being the first ecumenical synod held in the Holy Land in more than a millennium, and because it involved not only Catholic, but also Orthodox, Armenian and Syriac prelates from the regions under the Frankish and Rhõmaîon administration, it has a highly symbolic significance because it demonstrated the new possibilities of the dialogue between the European and Asian Churches resultant of the settlement of the Franks after the First Crusade. Its objective, however, was not to delve into doctrinal or theological controversies - it seems that Pope *Lucius III indeed intended to summon another ecumenical council to address these matters, but he would not live enough to see it fulfilled - but rather in more “mundane” aspects of the local religious institutions, such as to solve disputes involving the distribution of serfs, slaves, benefices and lands to the monasteries and the armed fraternities and to prosecute accusations of simony, and even of heresy, directed against purported adepts of Nestorianism in northern Syria, under the suzerainty of Damascus. All of these proceedings, especially the inquiries of heresy, in fact, created an awkward sentiment in the native Syriac clergy, because their religious practices were markedly different from both the Catholic and Orthodox ones, and, in spite of being subjects of the Crusader State and of the Empire, they never sought adhesion to the Catholic or Orthodox rites.

One important event was the accusation of clerical indiscipline forwarded against Bernard by the Cenacularians. Indeed, they argued that Bernard, by actually engaging in military campaigning and even in battles and sieges, had produced grave offenses and incurred in sins of pride and wrath. The Archbishop, used as he was to the exercise of political power, was disconcerted to see himself as a defendant in an ad hoc ecclesiastical court, where he lacked influence. The accusations, grave as they were, endangered Bernard’s political position; Cardinal John, accordingly, issued a suspension order against Bernard, and, as a substitute, until the end of the trial, was placed in the Archepiscopalian chair another Italian Cardinal,

Walter of Albano [Ita.

Gualtiero d’Albano]. Bernard immediately sent emissaries to Rome so as to appeal directly to the Pope.

The Holy Father, however, did not deign to appreciate his appeal before judgment was passed in the synod of Jerusalem. It did came to happen only in the week preceding Christmas, after which the court was adjourned to the following year. The court, by a significant majority, condemned Bernard for having instigated, and, in some cases, actually participated in acts of violence involving Christians. His sentence was of deposition from his office, and thus his position was Archbishop was voided, although he, after public acts of penance during Christmas - by which he dressed as a beggar and, deprived from food, he mortified himself by staying afoot in the cold of winter in the top of the Calvary over the course of two weeks, until the day of Epiphany, when he was once again welcomed into Jerusalem - he retained the

pallium, even though his ascending career was effectively over. After this, he returned to Italy, and, after failing to overturn his sentence, even more so because Pope Lucius died before he could appreciate the appeal, and his successor

Pope Sylvester was anything but sympathetic to his cause, Bernard would eventually abandon hopes for receiving another position, and devote himself to monastic life, whereupon he disappears from History.

Walter of Albano, despite being a Cardinal-Bishop himself, accepted the office of the Archbishopric, seeing it as a more prestigious position due to the association with the Holy City of Jerusalem.

******

The judgment of the lay princes was initiated only after the inquiries of the clergy finished, already in January 1171 A.D.

The trial was conducted simultaneously with the synod, but, seeing that a matter of non-ecclesiastical nature had to be decided by another institution, an ad hoc court of clergy and lay nobles was installed by the decree of the Chamberlain. The participants of this court of justice, then, were three prelates - Walter of Albano, Raynald of Gaeta [Ita.

Rainaldo di Gaeta], and Henry of Beauvais - and three laymen - Robert of Émèse, Henry Doria [Ita.

Enrico Doria], the Genoese governor of Jaffa, Paul Morosini [Ita.

Paolo Morosini], a Venetian Patrician who was, at the time, Chancellor of Jerusalem. It seems that they were chosen out of the expectation of impartiality, being unrelated by marriage or evident political interests to the ruling lords of the Realm, and unlikely to favor any of the involved parties.

The verdict was favorable to Bohemond, and it is probable that personal sympathies greatly benefited him in this trial, whose result was much more political than legal; Bohemond was the (maternal) grandson of the most famous Prince of Jerusalem, who had, now decades after his death, achieved a fabled reputation, and was seen as a worthy inheritor of the genuine Crusadist tradition and ideology. Besides, in person, he was well regarded by the Italian nobles resident in Jerusalem, considering that he had, before his exile, granted them extensive estates in Phoenicia, as well as commercial privileges. To avoid a genuine condemnation due to the ascribed sins of violence perpetrated during the war, he also provided a public demonstration of penance, as did his former associates, Richard of Arca and Mabel of Damascus.

In the case of Richard of Arca, his usurpation against his nephew William was also condemned, but he, perhaps seeing that challenging it would yield worse results, accepted the verdict and abdicated from his position as Lord of Tripoli, and resigned also from the regency to his restored liege. As his later actions demonstrate, however, he, in this event, was simply biding his time. Soon enough he would press his claim to the county once again.

The problem, however, was that the court also confirmed Raymond’s position as the sole Prince of Jerusalem and Duke of Galilee. Despite the fact that it seemed to exist a lingering desire from the nobles to call for another election, John of Naples emphasized that Prince Raymond had been elevated not by Bernard’s fiat but rather by the authority delegated to him by the Supreme Pontiff himself, and the fact that Bernard was now deposed was irrelevant, and did not void Raymond’s elevation. Thus, it would have been awkward to the judges to interfere in this matter, lest they might be seen as usurpers of Papal prerogatives.

In any event, this was evidently a political defeat for the Provençal nobleman and his partisans, because they expected that the High Court’s previous sentence, condemning Bohemond and ordering his exile, would be upholded. Now, the blocs of influence, pitting the Prince of Jerusalem, Tiberias and Tortosa, in one side, and Tyre, Damascus and, indirectly, Tripoli, in another - with the others, from Emèse, Beirut and Transjordania, apparently unaffiliated and more interested in preserving the status quo. However, the overall result was that Raymond’s political position was severely weakened; he had to admit that he lacked actual suzerainty or agency in the affairs of the Latin-Levantine grandees, who were, by now, quasi-independent, and would not accept Raymond’s preeminence. The seeds of another conflict were again sowed, especially because, to his allies, Bohemond made no secret that he desired the princely crown, and his claim had been supported by the Sicilians and by the most formidable of the Latin-Levantine magnates.

Then, by the time that the Pontifical committee departed from Palestine, the animosity between the former belligerents only grew. Walter of Albano was, much like other of his predecessors such as Gregory and Suger, a pragmatist, but he would fail to thwart another military escalation involving these same lords.

The Sicilians and Latin-Levantines go to the Sea

With the advent of spring, 1171 A.D., five or six galleys came from Italy and harbored in Tyre. They presented the flag of the Republic of Ancona, but they were, in fact, Amalfitan vessels under service of Prince William of Sicily; the deception permitted them to voyage from the peninsula to the eastern Mediterranean unmolested, safe from the surveillance of the Rhõmaîon warships, who, after two years, were counter-attacking Maio of Bari’s forays against the Mediterranean provinces of the Empire.

The Sicilians and Amalfitans were welcomed by Bohemond, who had only recently been recognized in Jerusalem as the legitimate ruler of the County of Tyre and the associated demesne and estates. In Tyre, the Italians were given supplies, weapons and a reinforcement of three hundred men-at-arms, whose commanders were Richard of Arca and Bohemond’s brother-in-law,

Roger “Felix” Drengot, the

Vidame of Banaïs de Chulam [i.e.

Banias of the Golan Mountains]. Not a few of the knights and soldiers of Tripoli deserted the suzerainty of the infant Count William and banded to the persona of Richard, who was a far more charismatic character.

From Tyre, they undertook various raids over the whole of the eastern Mediterranean, directed against the imperial provinces. It seems that their objective was not to wage a war of conquest, but rather to distract Constantinople to, perhaps, facilitate the advances of

Maio of Bari in the Aegean and in the Adriatic Seas. Thus, they acted much like pirates, seeking easy victories against unprotected harbors and merchant ships, and avoiding naval confrontation.

Laodicaea was the first to fall. It was the main port of the Empire in Syria, but the city had been severely damaged by an earthquake that happened in June 1170 A.D., one that devastated the main urban settlements of the region, from Antioch and Aleppo all the way to Ahmàt [Syr.

Hama], and its defenses had yet to be properly rebuilt. In the places where the stone curtains collapsed, the local garrison placed improvised wooden palisades, likely not expecting a seaborne attack. Once the attackers disembarked and destroyed the defenses, the local garrison capitulated without fight; they were too few to resist. They were made prisoners and forced to man the galley’s oars.

Afterwards, the Normans entered Cyprus, by the way of Limassol. After the Egyptian War, during which the island had served as an important base of naval and logistical supply, no greater care was given to its military protection, considering that the Empire did not expect to face any threats whatsoever in the region: the Fāṭimīds lacked a navy, and the Latin-Levantines were friendly and allied. Thus, it came as a shock that these ships, holstering the symbols of Ancona, were actually hostiles; their deception allowed them free passage into the harbor, and, once they had disembarked, it was easy enough to overpower the local garrison and then imprison them. Still under deceptive disguise, they were welcomed in Nicosia by the local governor, an elderly captain of Armenian origin named Abraham [Arm.

Avrahamos], who believed them to be merchants and mercenaries, and put his bodyguards to death in a brief engagement. Abraham was also made a prisoner and hostage, and over the course of almost a whole month, Richard and Roger and their men had free reins to perpetrate various heinous acts, plundering, raping and enslaving the hapless Cypriots. They only departed after the irate peasants banded together into an impromptu militia and killed some of their men while they were drunk in a feast in Nicosia.

When the court in Constantinople finally reacted the news about the plundering of Laodicaea and Cyprus - at first believing that it was an act of treachery from the Anconitans - they had to deploy a reserve war-fleet, established in Crete, to scour the sea against these freebooters. At the time, Manuel was campaigning in Apulia, and thus the imperial domestic affairs were under the purview of his elder son,

Alexios Porphyrogenitus [Gre.

Aléxios hoPorphyrogénnētos], who was then in Thessalonica.

The fleet intercepted them off the coast of Attaleia, after they had fattened their bags of plunder with the loot from the defeated town of Kalonoros, former Coracesium [Tur.

Alanya], and, rather surprisingly, they managed to flee, courtesy of a storm that wrecked some of the Rhõmaîon

dromonoi.

By the end of 1171 A.D., the Rhõmaîoi had demonstrated their clear military superiority by reducing various fortresses in Apulia, which made these naval forays of little to no strategic value in the grand scheme of the war. Maio of Bari was forced to abandon his project of an amphibious invasion of Greece, and had to return with his galleys to defend the island of Sicily itself, once an (real) Anconitan fleet allied to the Komnenoi outmaneuvered him, bypassing Calabria and going as far as Syracuse, which was captured and ransacked.

After peace was established between Rhõmanía and Sicily, Manuel did not forgot about the hostile acts perpetrated by the Latin-Levantine men allied to the Sicilians, and, soon enough, before 1172 A.D. dawned, he was preparing another military expedition to punish all those who had offended the integrity of the Empire and of its citizens.

Manuel Komnenos Marches into the Outremer

As we have aforementioned, the political context of the Crusader State saw various changes since the Egyptian Crusade. For the first time, a seated Archbishop of the Diocese of the Holy Land had been deposed, and held accountable for political acts.

Despite the fact that the trial of 1171 A.D. had expressly recognized Raymond-Jordan [III] as the legitimate Prince of Jerusalem and Duke of Galilee, it had also resumed the

status quo ante bellum by granting a general pardon to the nobles that had opposed him and Bernard, chief among them being Bohemond [II], Count of Tyre.

Now, this left Raymond in a precarious position, from a political standpoint. While Bernard’s erratic decisions had brought intestine conflict in the Realm, Raymond knew that he had been his principal benefactor and colleague, and no other Apostolic Legate would adopt the same stance towards him.

To him (and to all the other

Poulain, for the matter) Walter of Albano was strange to his causes and to the relevant matters that resulted in the disputes between the armed aristocrats. In fact, his life work in the Orient was dedicated to the organization of the Latin Church’s institutions and to his attempts of bringing the native liturgies - Syriac and Armenian - into accordance with the Catholic one. While he was very much concerned with the episodes of fratricide violence between the Latin-Levantine lords, he saw their disputes as beneath him, and earnestly believed that the correct and conscientious exercise of his judicial prerogatives as the Apostolic Legate in Jerusalem would be enough to pacify conflicts and quench animosities. In this regard, it seems that he grossly misunderstood the context of the political and military struggles involving the Provençals and the Normans and their respective allies.

Raymond’s authority as Prince had been gravely undermined. If his allies in Tiberias and Tortosa remained steadfast and supported him, they did so only due to familial bonds and in evident expectation of favoritism and patronage, but others, notably those of Damascus and Tyre, remained inimical to him. He realized that the nobles might have finally accepted his elevation to the head of the principality by Papal

fiat, but they denied him obedience.

In fact, Bohemond had, even after the truce, refused to surrender the fortress of Saflat, which pertained to the domain of Tiberias, Raymond’s brother-in-law. Raymond issued an ultimatum to Bohemond to either surrender Saflat or to destroy its fortifications, but the Count of Tyre refused to do so, affirming that Tiberias lacked the necessary manpower to garrison it, and that these defensive structures were necessary to protect the Jordan valley from the incursions of the Muslims into Palestine. Saflat, however, is distant less than a single day’s march to Tiberias or to Acre, and thus Raymond and Godfrey were sure to fear Bohemond’s presence so near them.

Raymond attempted to obtain the support of

Paul Morosini, the Chancellor of Jerusalem, who was also the

Viceduke of Transjordania, by promising him the grant of all the lands, benefices and castles as a hereditary allodial patrimony. The Viceduke, however, an elderly Venetian aristocrat of mild disposition, devoted his attention to commerce instead of to war, and knew that this was but an empty promise, as it was dependent on Papal sanction. In any event, when Raymond attempted to extract from the Viceduke the promise of joining him in another war against Bohemond to take Saflat, the latter refused, being wholly unwilling to participate in the bloodshed against Christians.

******

In the summer of 1173 A.D., Manuel marched from Aleppo into the Crusader State, at the head of an army comprising perhaps more than seven thousand soldiers. His intent was not clear at first; the anxious Archbishop Walter perhaps expected that his objective was to, once again, invade Egypt. He attempted to convince him otherwise, arguing that Palestine lacked the necessary resources to nourish his men during the march.

Soon, however, the Archbishop found out that Raymond and Godfrey too had mustered their knights, and then the Basileus’ intent became clear. His ambassador in Jerusalem, heeding the imperial envoys, communicated that the autocrat had come to punish transgressions and violations of the laws of God and of the Empire, perpetrated by Bohemond of Tyre, by Mabel of Damascus and by Richard of Arca, as by other nobles and commoners associated to them. He argued that they, moved greedily and contumely, had created a state of unlawful violence in the Holy Land, and usurped the lands and honors that pertained to the Realm.

While the sources do not attest it clearly, it seems that Raymond, having failed to extol obeisance from the Norman lords, presented his case directly to the Basileus;

John Kinnamos records that, in the year before that, William-Berengar, Raymond’s brother, was received with honors in Constantinople, and to him and to Raymond, the Basileus granted the honorifics of

Hypatos and

Patrikios. Afterwards, William-Berengar remained attached to the Basileus’ retinue until his coming to Jerusalem. This hardly seems a coincidence, and it is likely that Raymond realized that remaining in Manuel’s grace would allow him to lever up his position in the Frankish Levant.

In any event, Manuel had reasons of his own to seek justice. The attacks of the bandoleers commanded by Richard and Roger Felix of Arca against Laodicea, Cyprus and the southern littoral of Asia Minor aroused his wrath - according to John Kinnamos, he, having heard about these raids while campaigning in Apulia, had summoned God’s vengeance, in the same way He had purged the Philistines.

Now, Manuel ordered these culprits to abandon their castles and arms to face the Emperor’s justice.

******

Theological and political incompatibilities notwithstanding, Manuel had, over the course of his reign, maintained good relations with the Latin Popes, especially with Stephen X and *Lucius III after him; with Lucius’ successor Sylvester IV was not different. Manuel officially acknowledged him as the legitimate holder of the Patriarchate of Rome, refusing to recognize the French-backed candidate Stephen XI. This, then, put Sylvester in an awkward position when he was informed by the emissaries of Constantinople that the Basileus had marched into the Holy Land with a large army; the newly-elevated Pope, who had already upholded the decretals of the I Synod of Jerusalem and of the sentence produced by the so-called "Ioannine Court”of 1171 A.D. (thusly called in reference to its president, Cardinal-Bishop John of Naples), urged Manuel to acknowledge and respect the authority which had produced a peaceful solution to the conflicts between the Crusader knights of Jerusalem, and to refrain from introducing an armed force into the Earthly Kingdom of God if not imbued with the intent of waging war against the infidels.

Manuel, however, answered that the Realm of God was under his protection as the Emperor, the commander-in-chief of God’s armies, and the high guardian of the Holy Sepulcher, and thus it was his mission too to purge the land from traitors of the faith and usurpers. He recognized Raymond III as the legitimate Prince of Jerusalem, but Bohemond, Richard and Mabel were decried as usurpers.

This time, however, there would be no trial. If before Manuel had opted for a more diplomatic and legalist approach, convening a judicial court of Frankish aristocrats to settle the disputes between the warring nobles, now he outright accused these Norman aristocrats of sedition and unlawful violence and demanded their immediate capitulation.

Bohemond’s refusal to acquiesce to the ultimatum resulted in a declaration of war.

Richard of Arca, who, after being deposed from the lordship of Tripoli, had been welcomed in Bohemond’s court as the Constable of Tyre, hastily assembled the sergeants and conscripted levies, hoping to thwart Manuel’s advance against Tyre.

This time the odds were wholly unbalanced against the Normans. They could not commit to a pitched battle, and thus they produced skirmishes in an attempt to force the Rhõmaîoi host to the more mountainous terrain of eastern Phoenicia - where their numerical disadvantage could be compensated -, but they were quickly outmaneuvered by the Turkish and Pecheneg light cavalry at service of the Empire, whose assaults in fact contained the Norman cavalry. Then, Bohemond saw himself entrapped in the

Litani valley and was forced to face battle. Enjoying superiority in numbers,

Megas Domestikos Alexios Axouch completed a pincer movement, encircling the Norman army. The bloodshed was enormous, and Richard of Arca perished in the melee, as did many Norman and Lombard knights, and hundreds of Syrian soldiers who had been conscripted to fight in this hopeless war.

The Count of Tyre himself, with a handful of men, fought his way out of the engagement and over the next following days attempted to muster his broken army, but, then, in desperation, he opted to flee to Hautchastel [OTL

Beaufort Castle]. He was intercepted by the Armenian rangers loyal to Tiberias. Thinking him to be a lesser knight, they killed him on the spot, and, only then, after retrieving his signet and his shield, did they bring him, the corpse already empty of soul, to their liege-lord, who, nonetheless, congratulated them for the grisly deed.

The Downfall of the Bohemondines

His son and successor, Bohemond III, attempted to negotiate terms for peace, but Manuel was resolute in unconditional capitulation. Tyre briefly entertained resistance, but if this could do something to preserve the honor of the Norman magnate, it did little to save what was now a hopeless cause. On the very first day that the trebuchets were employed against the fortifications, Bohemond opened the gates and bent the knee.

The Rhõmaîon autocrat demonstrated no mercy to the Bohemondines. Proclaiming that they had been pardoned once, now their crimes could not be tolerated, even more so because they had marred with violence the sanctity of the Earthly Kingdom of God. Bohemond III was deposed and stripped from his titles, as were his closest relatives and his immediate vassals and retainers. They were then forced into an ignominious exile and would return to Europe in dishonor. And so it ended, after three generations, the Hauteville dominion in the Orient, one that had been forged from the crumbling edifice of the Islamic principalities by the audacity of Bohemond of Taranto. In the end, his nemeses, the Rhōmaîoi, had triumphed, and eradicated his lineage and legacy in the Holy Land. Although his cognates in Sicily would endure as champions of the Crusader heritage, notably in the prosecution of holy wars in Africa, Bohemond’s own progeny would fade from History after 1173 A.D.

The lands and estates that comprised the former County of Tyre were given by the Basileus to

Doux Andronikos Dalassenos Komnenos - Manuel’s brother-in-law, and who was, in fact, of Norman descent, his grandfather having been one of the veterans of the war of Robert Guiscard who defected to Rhõmaîon cause. He had some familiarity with the Norman language and respectful of his ancestry, so he was expected to be a more palatable candidate to placate the Frankish minor aristocrats and gentry who were now forced to pay homage to him.

At the time, the Lateran could do little in regards to Manuel’s intervention. Pope Sylvester protested against the fraternal violence between those imbued with the will of pilgrimage and crusading; however, he was much more concerned by the revolutions of the Stefanese Schism and the subsequent war between the King of France and the Kaiser, and the situation in the Outremer soon enough became a

faît accompli.

******

Unlike in the previous years, this time Mabel of Damascus did not come to the succor of the Tyrians. At the time, she was pregnant, awaiting what would be her second son, this one sired by her new husband, Ralph de Warenne, who had only recently departed to England, where he intended to procure money to sustain his fief and free men and their families willing to settle in Syria.

Manuel, during his brief stay in Jerusalem, during which he had left his army garrisoned in Saflat and in Caesarea, summoned the Archbishop and the Frankish lords and bade them to renew their oaths to him as their liege-lord. Mabel refused to allow her son, the Count of Damascus, to join the gathering, arguing that he was but a child, and she herself was carrying a baby in her womb, meaning that neither of them could afford the risks of travelling overland.

Nonetheless, seeing that she had been part of the same conspiracy that had attempted to dethrone Raymond years ago, Manuel decided Damascus had to give a demonstration of obeisance as well, and there he went to, accompanied by his guard as well as by Walter of Albano, and by the lords of Caesarea, Tiberias, Tortosa and Transjordania. In Damascus, they were received with honors and feast by the infant

Count Roger - then aged 10 years-old - and Mabel, in her capacity as regent and steward. Silently withstanding the humiliation, Mabel saw her son being admonished to prostrate himself and pay homage to the Basileus, but the worst she suffered was seeing him be taken as a hostage to Constantinople, with other sons of Frankish nobles, to receive education in the imperial court. To add insult to injury, Manuel voided her position as regent, and installed

Gerard of Aigremont, the Grandmaster of the Templarians, as the

ad hoc governor of Damascus until Roger came of age.

As it happened, then, the rapid and unforeseen destitution of the Bohemondines shocked their former colleagues among the Frankish aristocracy that ruled and governed the Outremer, and bred discontentment against the Manueline suzerainty. Indeed, the Franks had grown all too accommodated to the status quo, one of a distant, albeit influential, sovereign, to whom they could pay only lip service of vassalage, without inconvenience to their own interests and agendas; now, Manuel had made it all too clear that he was the ultimate master of the fates of the Outremer, and that the Franks were supposed to be his attendants, or, worse even, his underlings.