You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

And All Nations Shall Gather To It - Volume I: The Abode of Peace

- Thread starter Ricard (i.e. Rdffigueira)

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 90 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

65. The Fall of the Fatimid Caliphate 66. The Third War Between the Crusaders Interlude 5. The "Crusader States" as Historiographic Models 67. The Twilight of the Seljuks 68. The Jews and the Crusades Friendly Request: Contribute to the newly created Tv tropes Page 69. The Prophesized Emperors (Part 1) A not-so brief comment about my ideas for the TLI'm pretty sure now that the crusaders have taken Damascus, the Rhomans are likely to take a harder view on the situation.

Instead of a hostile Damascus that learned not to trust Crusaders against their fellow Muslim, we now have a thoroughly subdued Frank-occupied city and countryside immediately around the city.

The Franks better dig in until the main Muslim army shows up. They've just been woken up by the rising threat of the Crusaders.

Which main Muslim army, is the bigger question.The Franks better dig in until the main Muslim army shows up. They've just been woken up by the rising threat of the Crusaders.

It could come from Egypt, it could come from Baghdad, it could come screaming out of the Arabian desert... or the one from Baghdad could get bogged down playing politics in Mosul, the Egyptians get diverted by a palace coup, and the Arabs dispersed by a sandstorm.

Probably something in between, but I don't expect a single 'Muslim army'. Not yet, anyway.

@TheNerd_ - Well, for the time being, the Latins have things under control, but we can expect that, even after the capture of Damascus, they will remain in a state of war readiness against a possible retaliation by the Islamic adversaries. In any case, there is a lot of stuff to happen yet.

@St. Just - the fate of Damascus will be subject of the next chapter. Without getting into details, I can anticipate that it will cause some... friction between the diverging interests of the Frankish noblemen. I'll be trying to put it online before sunday, so we won't wait too long.

@StrikeEcho - precisely... I doubt the Emperor will get too happy about a bunch of Normans taking Damascus without some satisfaction. We'll see how it will unfold! It is but a matter of time before we see events that will strain the relationship between the Crusaders and the Byzantines.

Though I promise we'll never get down to the Fourth Crusade level of fuck-uppery.

@TyranicusMaximus - indeed, it is a great acquisition to the Crusader State. But the Turks will be sure to try and make the Crusaders pay an even bigger price for it. History unfortunately proves that in this kind of war, there cannot be a lasting peace, until one of the sides collapses.

@cmakk1012 - yeah... you can imagine that the Byzantines don't feel really too happy about it. You can be certain that they are well aware on about how the Crusaders depend on the Empire to actually survive. But I figure they believe it is better to babysit the Crusaders than to be surrounded by a bunch of Turkic invaders. John Komnenos could be the sort of guy that put these things in the balance: "well, they are going a bit too far, but then, again, they did was some good favor in helping to recover Anatolia".

@Joriz Castillo - *Jihad intensifies* | it is worth mentioning that by 1140s the Crusaders have already built their own share of castles in the Outremer, but they are more focused on Palestine and Lebanon. Syria, as a whole, is less protected, and its defensive macro-strategic structure is centered around the network of fortified cities, most notably Homs, Aleppo and Damascus.

@avernite - indeed, you've brought up a very good point! But, for the time being, we see that the more likely of these parties to attempt a round of war against the Crusaders would be the Seljuks. The Fatimids are still in a sorry shape - although the fall of Damascus might stir up a great deal of paranoia, mind you - and the Arabs... well, they don't do that much beyond go raiding some frontier settlements and caravans. You'll see, however, that you are right in the respect that the "Muslim army" will be a mish-mash effort of war.

@Icedaemon - I know, I sometimes change the POV of the narrative mid-chapter. Sometimes it gets confusing when I revise the text, and it might be detrimental to reading in post-format. Nevertheless, my point is to give a "broad picture" of the wars, so that you see it both from the perspective of the conquerors and of the conquered. With this, I hope, we have a less biased and more impartial view of (a)historical events.

As a rule of thumb, the narrative POV is that of a non-contemporary historian retelling contemporary souces (think of Edward Gibbon mentioning all the ancient Historians).

@St. Just - the fate of Damascus will be subject of the next chapter. Without getting into details, I can anticipate that it will cause some... friction between the diverging interests of the Frankish noblemen. I'll be trying to put it online before sunday, so we won't wait too long.

@StrikeEcho - precisely... I doubt the Emperor will get too happy about a bunch of Normans taking Damascus without some satisfaction. We'll see how it will unfold! It is but a matter of time before we see events that will strain the relationship between the Crusaders and the Byzantines.

Though I promise we'll never get down to the Fourth Crusade level of fuck-uppery.

@TyranicusMaximus - indeed, it is a great acquisition to the Crusader State. But the Turks will be sure to try and make the Crusaders pay an even bigger price for it. History unfortunately proves that in this kind of war, there cannot be a lasting peace, until one of the sides collapses.

@cmakk1012 - yeah... you can imagine that the Byzantines don't feel really too happy about it. You can be certain that they are well aware on about how the Crusaders depend on the Empire to actually survive. But I figure they believe it is better to babysit the Crusaders than to be surrounded by a bunch of Turkic invaders. John Komnenos could be the sort of guy that put these things in the balance: "well, they are going a bit too far, but then, again, they did was some good favor in helping to recover Anatolia".

@Joriz Castillo - *Jihad intensifies* | it is worth mentioning that by 1140s the Crusaders have already built their own share of castles in the Outremer, but they are more focused on Palestine and Lebanon. Syria, as a whole, is less protected, and its defensive macro-strategic structure is centered around the network of fortified cities, most notably Homs, Aleppo and Damascus.

@avernite - indeed, you've brought up a very good point! But, for the time being, we see that the more likely of these parties to attempt a round of war against the Crusaders would be the Seljuks. The Fatimids are still in a sorry shape - although the fall of Damascus might stir up a great deal of paranoia, mind you - and the Arabs... well, they don't do that much beyond go raiding some frontier settlements and caravans. You'll see, however, that you are right in the respect that the "Muslim army" will be a mish-mash effort of war.

@Icedaemon - I know, I sometimes change the POV of the narrative mid-chapter. Sometimes it gets confusing when I revise the text, and it might be detrimental to reading in post-format. Nevertheless, my point is to give a "broad picture" of the wars, so that you see it both from the perspective of the conquerors and of the conquered. With this, I hope, we have a less biased and more impartial view of (a)historical events.

As a rule of thumb, the narrative POV is that of a non-contemporary historian retelling contemporary souces (think of Edward Gibbon mentioning all the ancient Historians).

@TyranicusMaximus - indeed, it is a great acquisition to the Crusader State. But the Turks will be sure to try and make the Crusaders pay an even bigger price for it. History unfortunately proves that in this kind of war, there cannot be a lasting peace, until one of the sides collapses.

With the crusader state now in control of Damascus though, any attempt to retake the holy land from the direction of Mesopotamia would have to either cross the Syrian Desert, which would be suicidal for anything more than small bands of lightly equipped people with camel-loads of supplies, or pass by Damascus. Meaning that even if Damascus becomes a site which from here on keeps changing hands between Christians and Muslims, Jerusalem is now much safer in terms of any potential threat from the east.

trajen777

Banned

My feeling has always been that the Crusaders greatest prob was never taking the Inner cities. By leaving Aleppo (Hama) in the north, Damascus to the east, Egypt to the South west, and Palymra, Petra to the open desert you would have great bases for raiders & invasions (as well as major centers of wealth and population to form armies. The coast and inland were developing farm land and wealth which each raid diminished. So with Growth and raids you were maybe breaking even in population and increased wealth (population for soldiers and wealth to arm them and bring in mercs and build forts). So if you take this inner ring and reduce the raids this area becomes more wealthy to support each expanding ring. Also as others have stated the taking of the key cities reduces the bases for attack and allows the Crusaders to attack and raid outward. The conquest of key centers also adds to these rings of wealth.

SO the key conquest of Damascus then Aleppo then Egypt would not only gain the value of these centers but massive secure growth to the inner original Crusader areas.

Great Job in the TL

SO the key conquest of Damascus then Aleppo then Egypt would not only gain the value of these centers but massive secure growth to the inner original Crusader areas.

Great Job in the TL

Last edited:

@Icedaemon - exactly this. The acquisition of Damascus secures the definitive border of the Crusader State in Syria. In fact, had the Crusaders IOTL succeeded in capturing it in the Historical Second Crusade, I believe it might have survived a bit longer than they did (in the least, because Nur ad-Din would not have been able to use it as a base to invade Egypt via Saladin's uncle).

It is a point that I intend to adress in a later chapter: the geography of the Fertile Crescent facilitates the establishment of a regional power in the Levant region, because it is effectivelly surrounded by deserts, excepting on the north, which, in itsef, is a mountainous and rugged region. From a strategic POV, once the Crusaders secure Syria, they will be in a much more secure position, barring the southwest side, whence they can be invaded by Egypt.

As you said, though, Jerusalem itself is fairly more secure than it was in, say, the 1120s.

@trajen777 - yes, you gave a very proper description of the "defense in depth" strategy used by the Crusaders, even IOTL (and by the Medieval European peoples in general). The demographic and economic center of the Crusader State, even more than Palestine (which is, obviously, of religious and political significance, but economically, not so much), is Lebanon and northwestern Syria, from whence they will take the larger part of their revenues and manpower. Now that the outlying regions of Syria are fairly preserved - either with the Latins, such as Damascus, or with the Byzantines, who now hold Aleppo and Antioch - we can seriously conceive a longer lasting "Outremer".

And, as you pointed out, we'll see a potentially exponential growth of the central regions once the peripheral sectors are militarily protected. It is good to remember that Levant was always the "backwater" region of the Islamic empires since the Abbasid Caliphate, so the the presence of the Crusaders will make it see a revival, especially as it becomes more integrated to the Byzantine and European markets.

And thanks for the compliment, good to see you around!

@Colonel flagg - they are. Always. And they should be. But they are confident that the arriving armies of the Second Crusade will give a much needed manpower boost so they can continue their wars of conquest. We'll see how this will unfold.

It is a point that I intend to adress in a later chapter: the geography of the Fertile Crescent facilitates the establishment of a regional power in the Levant region, because it is effectivelly surrounded by deserts, excepting on the north, which, in itsef, is a mountainous and rugged region. From a strategic POV, once the Crusaders secure Syria, they will be in a much more secure position, barring the southwest side, whence they can be invaded by Egypt.

As you said, though, Jerusalem itself is fairly more secure than it was in, say, the 1120s.

@trajen777 - yes, you gave a very proper description of the "defense in depth" strategy used by the Crusaders, even IOTL (and by the Medieval European peoples in general). The demographic and economic center of the Crusader State, even more than Palestine (which is, obviously, of religious and political significance, but economically, not so much), is Lebanon and northwestern Syria, from whence they will take the larger part of their revenues and manpower. Now that the outlying regions of Syria are fairly preserved - either with the Latins, such as Damascus, or with the Byzantines, who now hold Aleppo and Antioch - we can seriously conceive a longer lasting "Outremer".

And, as you pointed out, we'll see a potentially exponential growth of the central regions once the peripheral sectors are militarily protected. It is good to remember that Levant was always the "backwater" region of the Islamic empires since the Abbasid Caliphate, so the the presence of the Crusaders will make it see a revival, especially as it becomes more integrated to the Byzantine and European markets.

And thanks for the compliment, good to see you around!

@Colonel flagg - they are. Always. And they should be. But they are confident that the arriving armies of the Second Crusade will give a much needed manpower boost so they can continue their wars of conquest. We'll see how this will unfold.

Correct me if I'm wrong but did the Crusaders just secure Damascus, before the bulk of the Second Crusade has arrived? Logically the next target would be Egypt? Even if they're somehow successful wouldn't they be so ridiculously overextended?

How will the Crusaders govern all these major acquisitions? I would think it'd be very decentralised. Perhaps we'll see a TTL-style Principality of Antioch in Damascus?

How will the Crusaders govern all these major acquisitions? I would think it'd be very decentralised. Perhaps we'll see a TTL-style Principality of Antioch in Damascus?

47. The Land of Damascus is Partitioned by the Franks (1137/1138 A.D.)

@Icedaemon - the current installment serves to address the question you and other readers presented

One narrative concept that fascinates me, in writing about the Crusaders, is the idea of having these European foreigners, inheritors of a Romano-Germanic sociocultural tapestry, finding the footprints and vestiges of various ancient Middle-Eastern civilizations, and how they would react in finding these different layers of various cultures. Evidently, all of their worldview is filtered by the Biblical narratives, and thus a significant emphasis is given to describe how this one or that other place are significant by the simple virtue that it is mentioned in the Scriptures. It is worth noting, however, that some of the mentions we'll see here actually come from the Islamic narratives; the Qu'ran does mentions various Biblical figures such as Abraham (Ibrahim), Noah and Jesus (Isa).

___________________________________________________________________________________

Damascus, called Dimashq by the Arabs, a city so ancient that even the meaning of its name has been lost in the streams of time, had been founded by a forgotten race of shepherds and fishermen upon a verdant riverplain, many years before the birth of Moses, while the Israelites still languished under under the whip of the Egyptian masters.

With brown clay and beige stones, one of Asia’s most proud metropolises was birthed in what seemed to be a fragment of Eden, a place fragrant of nutmeg and aspen.

It is gently caressed by a turquoise-colored river, whose eternal march conducts it from the mountains of Lebanon to the unforgiving deserts haunted by the djinni. The Franks call the river Abana (or Amana), because it is thusly named in the Bible, but the ancient Greeks, marveled by the opulence and wealth of the city itself, prefered to name it “Chrysorrhoas”, the gold stream. On the other hand, the Syrians and the Arabs, know it simply as “Barada”, which means “cold”, a marvelous relief for any traveler coming from the windswept dunes of Arabia and eastern Syria.

The fragrant land surrounding Damascus is named Goulta [Arabic. Ghūṭah/al-Ghouta], a country replete of nut gardens, aspens, graperies and olive groves, cultivated by a thousand generations, ever since the sons of Noah repopulated the Earth. The most famous of these commodities is apricot fruit, more commonsly known as damascene. It was but a matter of time before the Crusaders, enamored with the apricot juice the Arabs named Qamar al-Din, well enjoyed during the fasting period of the Ramadan, bring it back to Europe as “Chamarradine”, whereupon it would explode in popularity, later in the 14th Century.

To the north, Damascus is overlooked by Mount Chaselium [Arabic: Qāsiyūn], a site so holy that many shrines had been built by the Arabs after they founded the Caliphate, and where the prayers of the pilgrims could echo in the Heavens. It was there that Adam and Eve sought refuge from the inclement weather after they were expelled from the divine garden, and, alas, it was also the fateful place where their son Cain would slay his brother Abel. Cursed and holy, it was still haunted by the laments of timeless ghosts who had seen the first years of the Creation when Abraham arrived there, in his journey from Ur to Canaan, and it is said that his prayers to God finally assuaged their suffering. When the Franks came to this mountain, they knew that Jesus himself had prayed in a cave in the slopes of Chaselium, and encountered a small Christian community inhabiting its outskirts, named Tarassalem [Tall al-Ṣālḥiyyah]. Out of piety and dutifulness, Prince Roger of Jerusalem ordered the construction of a church to consacrate the place and a fortress to protect it.

Even in the age of the Crusades, the city of Damascus still conserved the urban planning of the ancient Romans. It was sectioned from west to east by a single straight road, the decumanus maximus; the Bāb al-Jābiyya, the western gate, was none other than the Gate of Jupiter, and the Bāb Sharqī in the east is the Gate of Sun, dedicated to Helios. Many of its contemporary buildings had been erected from the bricks of ruined pagan sanctuaries, fountains and baths.

After Theodosius Augustus unleashed the final blow against the declining pagan traditions, in the 4th Century A.D., Damascus was adorned with a hundred basilicas, owing to the reverence of the old Syrian aristocracy, all while the "New Rome" of Constantine greedily hoarded the wealth of the Empire to embellish itself in a very puerile effort to surpass Alexandria and Antioch. Centuries later, the city was integrated into the Islamic Caliphate, and it was during the golden days of the Umayyads that it saw its demographic, economic, social, cultural and architectural apogee, as they elevated from a major trading hub to an opulent and magnificent capitol. The envious Abbasids would elect Baghdad in the Euphrates to become the sun of their immense constellation of provinces, and thus Damascus, neglected and later exploited by the rapacity of a succession of tyrants – Bedouins, Egyptians and Turcomans –, was to experience a grueling decline between the 8th and 11th Centuries.

By the time the Crusaders made themselves their masters, the metropolis was once again flourishing, aged as it was, enriched by the commerce from Persia, India and Arabia. Now, it would yet again see its soaring minarets be felled and velvet-colored crosses be placed above its sanctuaries… where so many voices had prayed, since the beginning of time, to a multitude of gods.

Predictably, the definition of who would be awarded the city of Damascus became a source of contention among the magnates, yet another situation in which the complicated feudal dynamics in the Latin-Levantine aristocracy created dispute.

Prince Roger, in spite of his announced intention of being created the sole lord over Damascus, in truth held better claim to it than any of the other lords; the province had been taken by conquest, after all, and they all had invested in the enterprise.

And what is the Prince of Jerusalem, indeed?

A King? No, of course not. There is only one King of Jerusalem, and He reigns in Heaven.

Yes, the Prince of Jerusalem is also a Duke, yes… but his suzerainty over the Frankish Counts and Barons exists solely in the realm of Palestine, not in Syria.

No, they are all vassals of the Holy See of St. Peter, and his permanent representative is the Archbishop of Jerusalem. The Prince of Jerusalem and Duke of Galilee is, at best, a primus inter pares, elected among his equals to oversee of the army of the guardians of the Holy Land. But the magnates had never sworn fealty to him, and neither did the grandmasters of the knightly-fraternities, or the consuls of Italy, as a matter of fact, whose allegiance was to their own republics.

Now, on the other hand, it seemed that Roger actually mustered support from his kinsmen and compatriots who hailed from Italy and Normandy, likely attracted by the promise of a larger share of the spoils and a more significant allotment of revenues from the conquered nation. Opposed to the Normans were, as usual, the nobles who shared the langue d’òc, from Toulouse and Aquitaine, championed by Pons of Caesarea, son of Bertrand and grandson of Raymond of St. Giles, one, who, however, had only regressed from Europe in the previous year, and had yet to entrench himself in the Outremerian political arena. Pons argued that Damascus, large and sprawling as it was – unlike any other in Europe, greater than even Rome –, could not be ruled by a single lord, lest it might welcome defiance from its denizens and perhaps even ease the attack of another Saracen tyrant. He proposed that the city was to be partitioned, with certain districts allotted to the noblemen, so that all of her citadels could be occupied by the Christian soldiers.

To Roger’s dismay, the Archbishop rapidly interfered in the deliberations, presenting himself as the sole arbiter of the matter; it was evident to Roger that the Italian prelate desired to increase his own influence and standing by positioning himself above the lay nobles. The Prince contested it, saying that the division of “spoils” was a question pertinent to the knights, and not to the churchmen, but Seneschal William of Sant’Angelo, whose piety made him an obedient attendant of the Archepiscopalian office, pressured Roger into accepting Gregory’s intercession.

Now, Gregory, even if not contrary to the idea of the Norman magnates having the control of Damascus – they were, indeed, formidable champions of the Holy Land and, together with the Lombards, comprised a substantial portion of the armed forces of the Principality – wanted concessions as a means to balance their political power, and in this he was widely supported by the other aristocrats, such as the Provençals and Aquitanians, as well as the Bavarians and the Lorrainers.

So, Roger was granted the Damascus as a whole and was created Count of Syria, but, as compensation, was pressured into relinquishing the County of Samaria, now awarded to Joscelin of Courtenay, a valiant French nobleman related to the House of Capet. Joscelin, who had spent most of his time in the East warring for the County of Edessa in fruitless wars against the Turkish emirs of Armenia, had recently retired to Tiberias, depleted of vigor by his advanced age. This owed to Joscelin’s dynastic pedigree and served to reward his services in the wars against the infidels, as well as to preserve the allegiance of the many Armenian knights [Armenian: Azatkʿ] employed in his household, all of whom had come to the Levant as protectors of Joscelin’s deceased Armenian wife, (re)baptized as Beatrice.

The final partition of the heartlands of Syria, which would comprise the namesake County, sponsored by Gregory, also dissatisfied Roger, who resented the deprivation of his (supposed) claim to the whole country. He was recognized as the titular of Tarassalem and its citadel, one that was enffeofed to William of Saint-Faramond [Italian: Guglielmo di Sanframondo], another Italo-Norman knight loyal to the House of Salerno, though he failed to secure other fiefs, such as the suburban village of Mezzania, awarded to Bishop Rainer of Rimini, one of Gregory’s lackeys, and the bastion of Daria, which became possession of Thomas of Roucy, one of the many sons of the Picard Count Ebles II, of the House of Montdidier, a prominent champion of the Iberian Crusades.

If Roger at the time really entertained any ambitions of becoming a monarch in Syria, he did not manifest them at this moment, grudgingly aware that the political conjuncture was not favorable to his pretense. Nevertheless, regardless of the circumstances, the fact remained that he was the paramount lord of the wealthiest and most fertile country in the Orient.

Early in 1138, another contingent of Crusaders arrived by the sea. It was the host led by Counts Theodorich of Flanders and Baldwin IV of Hainaut, as well as by the English and (Francian) Norman earls under the banner of Robert of Caen. They were supposed to come by the overland route crossing Anatolia, but, while in Constantinople, the Count of Flanders impressed John Komnenos with his cultured manners and dignified bearing, and so the Emperor provided a squadron of galleys to transport them by sea. The disembark in Acre happened weeks before they were expected to arrive and, once again, they were welcomed with festivity and celebration.

Once the armed pilgrims fulfilled their duties to the faith, and visited the most famous sites, from the Holy Sepulcher to the Jordan river, where the Archbishop presided over a collective baptism, they became eager to adventure in this mythical realm, astonished as they were by the sparkling wealth accumulated by the Franco-Levantine magnates. However, the approach of winter discouraged immediate military action, and thus they were disbanded to await for the next season.

Yet another unexpected happenstance occurred in the meantime: together with the Flemish, the Lorrainers and the English, came from Constantinople an illustrious cortege of Rhōmaîon dignitaries, whose chief was John Dalassenos [Greek: Ioannes Dalassenos/Ioannes Rogerios], the son of a Norman lieutenant who had defected to the Empire after Robert Guiscard’s invasion of Greece. Awarded with the title of Caesar [Greek: Kaisar], Dalassenos announced himself the herald of the most august Basileus (and also his own father-in-law, being he married to Maria Komnene).

If previously Constantinople had shown plenty of goodwill, now the circumstances had changed, and the Latins knew it. Dalassenos, in spite of his Norman heritage, had no particular sympathy to the Franks, and performed well his role as the voice of the Basileus.

Initially, the Crusaders were praised and applauded the Rhōmaîon envoys, as champions of the Christ and of the Holy Land, for their impressive conquest of Damascus. From acclaim, they were soon met with admonition and repproach. Indeed, considering they owed allegiance to the Throne of Constantinople, ought not they have previously informed to the most august sovereign of their intent of putting Damascus to siege? Indeed, they knew all too well that the Rhōmaîoi were also avid to join the holiest expedition to deliver the faithful peoples from the yoke of the infidel. And, even now, had they not witheld the due share of the spoils and tributes from Damascus to Constantinople, as per their obligations to surrender a part the hoard collected from the vanquished nation? Had they too not forgotten to correspond to the Court about the situation and the welfare of the [Orthodox] Christians that inhabited the Syrian metropolis, all of these souls which are ever under Imperial protection?

It is said – at least it what one can read from the Rhōmaîon sources – that the Frankish lords were full of shame and embarrassment after the Emperor’s voice was brought to them by Caesar Dalassenos, and that a formal letter of apology, signed by the highest noblemen and knights alike, was sent to implore the sovereign’s clemency. If such a document really existed, we can never know, as no Latin source mentions it; and if it was real, it certainly was not sincere.

Nevertheless, the Franks were duly aware about the value of maintaining their friendship with the Komnenoi – considering their shared political, economic and military interests in the Outremer –, reason by which savvy and scrupulous statesmen such as the Archbishop and William of Sant’Angelo quickly acted to repair any fissures in this relationship arising from the Damascene question. From diplomatic concessions and material quittance, the Latins went to great length to collect a hoard of treasure intended to gift the Constantinopolitan Court. Needless to say, this scandalized Roger of Salerno and his Norman partisans, as they were coerced into ceding a substantial portion of the vindicated Syrian treasure to appease what he saw as dissolute Greek sycophants. Their irresignation, however, was in vain. By early 1139, the Archbishop, supported by his most stalwart ally, the Provençal Count of Caesarea – united by their mutual rivalry towards the Normans –, had furnished a barge replete with precious stones, broidered cloth, Indian and Arabic spices, citric fruits, Saracen slaves, and even some exotic animals which had embellished Baqtash’s palace. It might be that these sorts of gifts would be rather miserable to the Sublime Court, famous for its proverbial wealth and exotic lavishness, but the intention was less to impress and more to appease.

To be fair, the Crusaders had nothing to fear about the purposed Imperial interests in the Near East; at the time, Constantinople was more concerned with restoring their former borders in eastern Anatolia and in northwestern Syria. The Franks, obsessed as they were with Syria, scantly realized that Rhōmania was more interested in (re)annexing the provinces of Armenia, all the way to the border with the friendly Kingdom of Georgia, and, from there, perhaps even retake western Mesopotamia, a feat that would confine the Turkic Sultanate to the lands beyond the Tigris river. The Komnenoi Emperors envisaged the Armenian mountains and the Mesopotamian rivers as the definitive natural borders of the Empire. Only after these areas are secure will they consider pronging deeper into Syria.

In conclusion, the diplomatic impasse was solved after some parleys, even more as the Basileus became convinced that the Franks would respect the rights and condition of the Orthodox subjects living in Syria. The “Frankokratia” in the Levant was a faît accompli, but it was a set of circumstances that the Rhōmaîoi could live with... as long as the Franks were mindful of their duties and of the deference owed to the Empire.

One narrative concept that fascinates me, in writing about the Crusaders, is the idea of having these European foreigners, inheritors of a Romano-Germanic sociocultural tapestry, finding the footprints and vestiges of various ancient Middle-Eastern civilizations, and how they would react in finding these different layers of various cultures. Evidently, all of their worldview is filtered by the Biblical narratives, and thus a significant emphasis is given to describe how this one or that other place are significant by the simple virtue that it is mentioned in the Scriptures. It is worth noting, however, that some of the mentions we'll see here actually come from the Islamic narratives; the Qu'ran does mentions various Biblical figures such as Abraham (Ibrahim), Noah and Jesus (Isa).

___________________________________________________________________________________

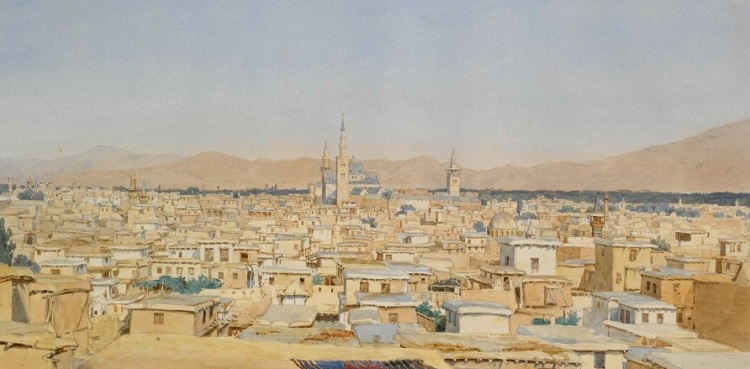

Non-contemporary painting of Damascus (c. 1500), then the capital of the realm of Syria

Damascus, called Dimashq by the Arabs, a city so ancient that even the meaning of its name has been lost in the streams of time, had been founded by a forgotten race of shepherds and fishermen upon a verdant riverplain, many years before the birth of Moses, while the Israelites still languished under under the whip of the Egyptian masters.

With brown clay and beige stones, one of Asia’s most proud metropolises was birthed in what seemed to be a fragment of Eden, a place fragrant of nutmeg and aspen.

It is gently caressed by a turquoise-colored river, whose eternal march conducts it from the mountains of Lebanon to the unforgiving deserts haunted by the djinni. The Franks call the river Abana (or Amana), because it is thusly named in the Bible, but the ancient Greeks, marveled by the opulence and wealth of the city itself, prefered to name it “Chrysorrhoas”, the gold stream. On the other hand, the Syrians and the Arabs, know it simply as “Barada”, which means “cold”, a marvelous relief for any traveler coming from the windswept dunes of Arabia and eastern Syria.

The fragrant land surrounding Damascus is named Goulta [Arabic. Ghūṭah/al-Ghouta], a country replete of nut gardens, aspens, graperies and olive groves, cultivated by a thousand generations, ever since the sons of Noah repopulated the Earth. The most famous of these commodities is apricot fruit, more commonsly known as damascene. It was but a matter of time before the Crusaders, enamored with the apricot juice the Arabs named Qamar al-Din, well enjoyed during the fasting period of the Ramadan, bring it back to Europe as “Chamarradine”, whereupon it would explode in popularity, later in the 14th Century.

To the north, Damascus is overlooked by Mount Chaselium [Arabic: Qāsiyūn], a site so holy that many shrines had been built by the Arabs after they founded the Caliphate, and where the prayers of the pilgrims could echo in the Heavens. It was there that Adam and Eve sought refuge from the inclement weather after they were expelled from the divine garden, and, alas, it was also the fateful place where their son Cain would slay his brother Abel. Cursed and holy, it was still haunted by the laments of timeless ghosts who had seen the first years of the Creation when Abraham arrived there, in his journey from Ur to Canaan, and it is said that his prayers to God finally assuaged their suffering. When the Franks came to this mountain, they knew that Jesus himself had prayed in a cave in the slopes of Chaselium, and encountered a small Christian community inhabiting its outskirts, named Tarassalem [Tall al-Ṣālḥiyyah]. Out of piety and dutifulness, Prince Roger of Jerusalem ordered the construction of a church to consacrate the place and a fortress to protect it.

Even in the age of the Crusades, the city of Damascus still conserved the urban planning of the ancient Romans. It was sectioned from west to east by a single straight road, the decumanus maximus; the Bāb al-Jābiyya, the western gate, was none other than the Gate of Jupiter, and the Bāb Sharqī in the east is the Gate of Sun, dedicated to Helios. Many of its contemporary buildings had been erected from the bricks of ruined pagan sanctuaries, fountains and baths.

After Theodosius Augustus unleashed the final blow against the declining pagan traditions, in the 4th Century A.D., Damascus was adorned with a hundred basilicas, owing to the reverence of the old Syrian aristocracy, all while the "New Rome" of Constantine greedily hoarded the wealth of the Empire to embellish itself in a very puerile effort to surpass Alexandria and Antioch. Centuries later, the city was integrated into the Islamic Caliphate, and it was during the golden days of the Umayyads that it saw its demographic, economic, social, cultural and architectural apogee, as they elevated from a major trading hub to an opulent and magnificent capitol. The envious Abbasids would elect Baghdad in the Euphrates to become the sun of their immense constellation of provinces, and thus Damascus, neglected and later exploited by the rapacity of a succession of tyrants – Bedouins, Egyptians and Turcomans –, was to experience a grueling decline between the 8th and 11th Centuries.

By the time the Crusaders made themselves their masters, the metropolis was once again flourishing, aged as it was, enriched by the commerce from Persia, India and Arabia. Now, it would yet again see its soaring minarets be felled and velvet-colored crosses be placed above its sanctuaries… where so many voices had prayed, since the beginning of time, to a multitude of gods.

*****

Predictably, the definition of who would be awarded the city of Damascus became a source of contention among the magnates, yet another situation in which the complicated feudal dynamics in the Latin-Levantine aristocracy created dispute.

Prince Roger, in spite of his announced intention of being created the sole lord over Damascus, in truth held better claim to it than any of the other lords; the province had been taken by conquest, after all, and they all had invested in the enterprise.

And what is the Prince of Jerusalem, indeed?

A King? No, of course not. There is only one King of Jerusalem, and He reigns in Heaven.

Yes, the Prince of Jerusalem is also a Duke, yes… but his suzerainty over the Frankish Counts and Barons exists solely in the realm of Palestine, not in Syria.

No, they are all vassals of the Holy See of St. Peter, and his permanent representative is the Archbishop of Jerusalem. The Prince of Jerusalem and Duke of Galilee is, at best, a primus inter pares, elected among his equals to oversee of the army of the guardians of the Holy Land. But the magnates had never sworn fealty to him, and neither did the grandmasters of the knightly-fraternities, or the consuls of Italy, as a matter of fact, whose allegiance was to their own republics.

Now, on the other hand, it seemed that Roger actually mustered support from his kinsmen and compatriots who hailed from Italy and Normandy, likely attracted by the promise of a larger share of the spoils and a more significant allotment of revenues from the conquered nation. Opposed to the Normans were, as usual, the nobles who shared the langue d’òc, from Toulouse and Aquitaine, championed by Pons of Caesarea, son of Bertrand and grandson of Raymond of St. Giles, one, who, however, had only regressed from Europe in the previous year, and had yet to entrench himself in the Outremerian political arena. Pons argued that Damascus, large and sprawling as it was – unlike any other in Europe, greater than even Rome –, could not be ruled by a single lord, lest it might welcome defiance from its denizens and perhaps even ease the attack of another Saracen tyrant. He proposed that the city was to be partitioned, with certain districts allotted to the noblemen, so that all of her citadels could be occupied by the Christian soldiers.

To Roger’s dismay, the Archbishop rapidly interfered in the deliberations, presenting himself as the sole arbiter of the matter; it was evident to Roger that the Italian prelate desired to increase his own influence and standing by positioning himself above the lay nobles. The Prince contested it, saying that the division of “spoils” was a question pertinent to the knights, and not to the churchmen, but Seneschal William of Sant’Angelo, whose piety made him an obedient attendant of the Archepiscopalian office, pressured Roger into accepting Gregory’s intercession.

Now, Gregory, even if not contrary to the idea of the Norman magnates having the control of Damascus – they were, indeed, formidable champions of the Holy Land and, together with the Lombards, comprised a substantial portion of the armed forces of the Principality – wanted concessions as a means to balance their political power, and in this he was widely supported by the other aristocrats, such as the Provençals and Aquitanians, as well as the Bavarians and the Lorrainers.

So, Roger was granted the Damascus as a whole and was created Count of Syria, but, as compensation, was pressured into relinquishing the County of Samaria, now awarded to Joscelin of Courtenay, a valiant French nobleman related to the House of Capet. Joscelin, who had spent most of his time in the East warring for the County of Edessa in fruitless wars against the Turkish emirs of Armenia, had recently retired to Tiberias, depleted of vigor by his advanced age. This owed to Joscelin’s dynastic pedigree and served to reward his services in the wars against the infidels, as well as to preserve the allegiance of the many Armenian knights [Armenian: Azatkʿ] employed in his household, all of whom had come to the Levant as protectors of Joscelin’s deceased Armenian wife, (re)baptized as Beatrice.

The final partition of the heartlands of Syria, which would comprise the namesake County, sponsored by Gregory, also dissatisfied Roger, who resented the deprivation of his (supposed) claim to the whole country. He was recognized as the titular of Tarassalem and its citadel, one that was enffeofed to William of Saint-Faramond [Italian: Guglielmo di Sanframondo], another Italo-Norman knight loyal to the House of Salerno, though he failed to secure other fiefs, such as the suburban village of Mezzania, awarded to Bishop Rainer of Rimini, one of Gregory’s lackeys, and the bastion of Daria, which became possession of Thomas of Roucy, one of the many sons of the Picard Count Ebles II, of the House of Montdidier, a prominent champion of the Iberian Crusades.

If Roger at the time really entertained any ambitions of becoming a monarch in Syria, he did not manifest them at this moment, grudgingly aware that the political conjuncture was not favorable to his pretense. Nevertheless, regardless of the circumstances, the fact remained that he was the paramount lord of the wealthiest and most fertile country in the Orient.

*****

Early in 1138, another contingent of Crusaders arrived by the sea. It was the host led by Counts Theodorich of Flanders and Baldwin IV of Hainaut, as well as by the English and (Francian) Norman earls under the banner of Robert of Caen. They were supposed to come by the overland route crossing Anatolia, but, while in Constantinople, the Count of Flanders impressed John Komnenos with his cultured manners and dignified bearing, and so the Emperor provided a squadron of galleys to transport them by sea. The disembark in Acre happened weeks before they were expected to arrive and, once again, they were welcomed with festivity and celebration.

Once the armed pilgrims fulfilled their duties to the faith, and visited the most famous sites, from the Holy Sepulcher to the Jordan river, where the Archbishop presided over a collective baptism, they became eager to adventure in this mythical realm, astonished as they were by the sparkling wealth accumulated by the Franco-Levantine magnates. However, the approach of winter discouraged immediate military action, and thus they were disbanded to await for the next season.

Yet another unexpected happenstance occurred in the meantime: together with the Flemish, the Lorrainers and the English, came from Constantinople an illustrious cortege of Rhōmaîon dignitaries, whose chief was John Dalassenos [Greek: Ioannes Dalassenos/Ioannes Rogerios], the son of a Norman lieutenant who had defected to the Empire after Robert Guiscard’s invasion of Greece. Awarded with the title of Caesar [Greek: Kaisar], Dalassenos announced himself the herald of the most august Basileus (and also his own father-in-law, being he married to Maria Komnene).

If previously Constantinople had shown plenty of goodwill, now the circumstances had changed, and the Latins knew it. Dalassenos, in spite of his Norman heritage, had no particular sympathy to the Franks, and performed well his role as the voice of the Basileus.

Initially, the Crusaders were praised and applauded the Rhōmaîon envoys, as champions of the Christ and of the Holy Land, for their impressive conquest of Damascus. From acclaim, they were soon met with admonition and repproach. Indeed, considering they owed allegiance to the Throne of Constantinople, ought not they have previously informed to the most august sovereign of their intent of putting Damascus to siege? Indeed, they knew all too well that the Rhōmaîoi were also avid to join the holiest expedition to deliver the faithful peoples from the yoke of the infidel. And, even now, had they not witheld the due share of the spoils and tributes from Damascus to Constantinople, as per their obligations to surrender a part the hoard collected from the vanquished nation? Had they too not forgotten to correspond to the Court about the situation and the welfare of the [Orthodox] Christians that inhabited the Syrian metropolis, all of these souls which are ever under Imperial protection?

It is said – at least it what one can read from the Rhōmaîon sources – that the Frankish lords were full of shame and embarrassment after the Emperor’s voice was brought to them by Caesar Dalassenos, and that a formal letter of apology, signed by the highest noblemen and knights alike, was sent to implore the sovereign’s clemency. If such a document really existed, we can never know, as no Latin source mentions it; and if it was real, it certainly was not sincere.

Nevertheless, the Franks were duly aware about the value of maintaining their friendship with the Komnenoi – considering their shared political, economic and military interests in the Outremer –, reason by which savvy and scrupulous statesmen such as the Archbishop and William of Sant’Angelo quickly acted to repair any fissures in this relationship arising from the Damascene question. From diplomatic concessions and material quittance, the Latins went to great length to collect a hoard of treasure intended to gift the Constantinopolitan Court. Needless to say, this scandalized Roger of Salerno and his Norman partisans, as they were coerced into ceding a substantial portion of the vindicated Syrian treasure to appease what he saw as dissolute Greek sycophants. Their irresignation, however, was in vain. By early 1139, the Archbishop, supported by his most stalwart ally, the Provençal Count of Caesarea – united by their mutual rivalry towards the Normans –, had furnished a barge replete with precious stones, broidered cloth, Indian and Arabic spices, citric fruits, Saracen slaves, and even some exotic animals which had embellished Baqtash’s palace. It might be that these sorts of gifts would be rather miserable to the Sublime Court, famous for its proverbial wealth and exotic lavishness, but the intention was less to impress and more to appease.

To be fair, the Crusaders had nothing to fear about the purposed Imperial interests in the Near East; at the time, Constantinople was more concerned with restoring their former borders in eastern Anatolia and in northwestern Syria. The Franks, obsessed as they were with Syria, scantly realized that Rhōmania was more interested in (re)annexing the provinces of Armenia, all the way to the border with the friendly Kingdom of Georgia, and, from there, perhaps even retake western Mesopotamia, a feat that would confine the Turkic Sultanate to the lands beyond the Tigris river. The Komnenoi Emperors envisaged the Armenian mountains and the Mesopotamian rivers as the definitive natural borders of the Empire. Only after these areas are secure will they consider pronging deeper into Syria.

In conclusion, the diplomatic impasse was solved after some parleys, even more as the Basileus became convinced that the Franks would respect the rights and condition of the Orthodox subjects living in Syria. The “Frankokratia” in the Levant was a faît accompli, but it was a set of circumstances that the Rhōmaîoi could live with... as long as the Franks were mindful of their duties and of the deference owed to the Empire.

Last edited:

jocay

Banned

To be the pedantic contrarian, it would slap if the Crusader State pursues maritime expansion - perhaps to establish a friendly trade connection between Christendom and India via the Red Sea. Capture key areas like the port of Aden, Socotra and the Dahlak archipelago perhaps in collaboration with the Italian city-states and the Christian Zagwe dynasty of Ethiopia. Maybe work out some sort of arrangement where the Ethiopian Church can be brought back to the fold? :3

Getting down to Ethiopia definitely sounds like a 15th-16th century sort of ambition -- maintaining control of Aden (let alone Socotra) without a deep presence in Egypt and the ability to protect ports from the Arabian polities would be difficult, especially given the number of hostile Muslim frontiers surrounding the Outremer and Egypt.

That being said, they'd probably have more ties with Medri Bahri (modern Eritrea) than the coastless Zagwes. A fun twist might be a Crusader expedition to restore an exiled "Solomonid" claimant -- that dynastic legacy would resonate deeply with the crusader elites.

As for the update -- Roger can be salty about the Greeks bearing gifts back to Constantinople and the schemes of Gregory, but Damascus is Damascus -- almost definitely the best prize in the Levant, given that Antioch and Aleppo are Roman.

I know it doesn't fit the current situation in the TL, but I can kind of see the beginnings of future Guelph-Ghibelline sorts of divisions in the Outremer. The non-Normans are, no matter the Archbishop, natural allies of imperial influence, given the deep-seated antagonism between all the branches of the Mediterranean Normans and the Roman Empire. The Normans, despite Gregory's political wizardry at the moment, therefore have more need of an institutional counterbalance against the Provencals and the Romans -- the Archbishop and more broadly the Papacy. I can definitely see the Normans playing up the "Ortho is heresy, muh filioque" issue and trying to become loyal advocates of future episcopal influence (post-Gregory, anyway), and I can conversely see the Provencals trying to build upon ties with the Romans (marriage perhaps, even between the future Kingdom of Aquitaine and Rome?) That also brings in another possibility -- the pseudo-international nature of Christendom's condominium in the Levant naturally brings in polities back in the metropole into Outremerian conflicts -- and that's even before we get to the Italians!

That being said, they'd probably have more ties with Medri Bahri (modern Eritrea) than the coastless Zagwes. A fun twist might be a Crusader expedition to restore an exiled "Solomonid" claimant -- that dynastic legacy would resonate deeply with the crusader elites.

As for the update -- Roger can be salty about the Greeks bearing gifts back to Constantinople and the schemes of Gregory, but Damascus is Damascus -- almost definitely the best prize in the Levant, given that Antioch and Aleppo are Roman.

I know it doesn't fit the current situation in the TL, but I can kind of see the beginnings of future Guelph-Ghibelline sorts of divisions in the Outremer. The non-Normans are, no matter the Archbishop, natural allies of imperial influence, given the deep-seated antagonism between all the branches of the Mediterranean Normans and the Roman Empire. The Normans, despite Gregory's political wizardry at the moment, therefore have more need of an institutional counterbalance against the Provencals and the Romans -- the Archbishop and more broadly the Papacy. I can definitely see the Normans playing up the "Ortho is heresy, muh filioque" issue and trying to become loyal advocates of future episcopal influence (post-Gregory, anyway), and I can conversely see the Provencals trying to build upon ties with the Romans (marriage perhaps, even between the future Kingdom of Aquitaine and Rome?) That also brings in another possibility -- the pseudo-international nature of Christendom's condominium in the Levant naturally brings in polities back in the metropole into Outremerian conflicts -- and that's even before we get to the Italians!

What's in there for the Provencal party? As I see, the spoils of Damascus mostly went to either Italo-Norman or Lorrainer parties. (well, I hoped to see Guilhem d'Acre, as I would call him in French, to achieve something of note even if I know Damascus was out of hand ^^)

Else, on the Byzantines, I guess one better way to remind the Franks of their reliance would be, in case the Franks find themselves suddenly overwhelmed by the Turkish counter-attack, to have them taking their time marching to their relief (but well, not too slow, as they would have to arrive before the royal hosts of France and England to have some impact). Basically, it's like what happened at Antioch ITTL when the Byzantines are seen as saving the day.

Else, on the Byzantines, I guess one better way to remind the Franks of their reliance would be, in case the Franks find themselves suddenly overwhelmed by the Turkish counter-attack, to have them taking their time marching to their relief (but well, not too slow, as they would have to arrive before the royal hosts of France and England to have some impact). Basically, it's like what happened at Antioch ITTL when the Byzantines are seen as saving the day.

Well, to begin with, as Rdffigueira is not too at ease with formal maps, I'd suggest a formal list of the feudal lords and lordships of the Levant, basically to say who rules what or what is ruled by who, along possibly the faction to which such or such lord belongs, who is an elector for the Prince-Ducal office, some economical/cultural detail or some brief (dynastic) history of the fief ... That could be a nice update to make another bilan of the region.It would be clear if we could have a map

Then, if someone is up to it, he could make a map from that in collaboration with the author.

Chickennuggetscientist

Banned

Have events in Iberia unfolded exactly as OTL? Assuming they have Toledo and Zaragoza were reconquered in 1085 and 1118 respectively. Around 1140 Portugal is about to assert itself as a fully independent kingdom after its defeat of Leon in the battle of Valdevez and the treaty of Zamora in 1143. It has already had de Facto independence which was strengthened by Afonzo's victory in the battle of Ourique. With more successful crusades in the Levant one would expect religious fervor and papal requests for Iberian crusades more commonplace, and also a bigger stream of crusaders fighting in the reconquista on their way to and from the holy land.

Also with the fall of Damascus moral would be weakened in the Almohad Caliphate which in OTL has just conquered al-Andalus. IMO less setbacks like the battle of Alarcos 1195 would happen.

Also with the fall of Damascus moral would be weakened in the Almohad Caliphate which in OTL has just conquered al-Andalus. IMO less setbacks like the battle of Alarcos 1195 would happen.

Threadmarks

View all 90 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

65. The Fall of the Fatimid Caliphate 66. The Third War Between the Crusaders Interlude 5. The "Crusader States" as Historiographic Models 67. The Twilight of the Seljuks 68. The Jews and the Crusades Friendly Request: Contribute to the newly created Tv tropes Page 69. The Prophesized Emperors (Part 1) A not-so brief comment about my ideas for the TL

Share: