Anahuac Triunfante: A more united and successful Mexico from Colony to Enduring Republic TL

Part 3: A New Republic

Chapter 7: The Northern Territories under Morelos 1822-1826

Integration of the Californias

Baja California territory didn’t see the evacuation of Spanish soldiers until several years after the effective end of the War of independence. The road that connected Durango to Guadalajara and Queretaro was extended to the cities of Sinaloa. Another road was built between Guadalajara and Sinaloa via Mazatlán, a growing port city on the pacific coast. These roads were funded by the states of Jalisco and Sonora with federal assistance. In 1822 Morelos got funding from congress to standardize the two roads and extend them from Sinaloa to Sonora City and then connect them to the California highway (originally called the royal road) by 1823 efectively connecting the two Californias to Mexico.

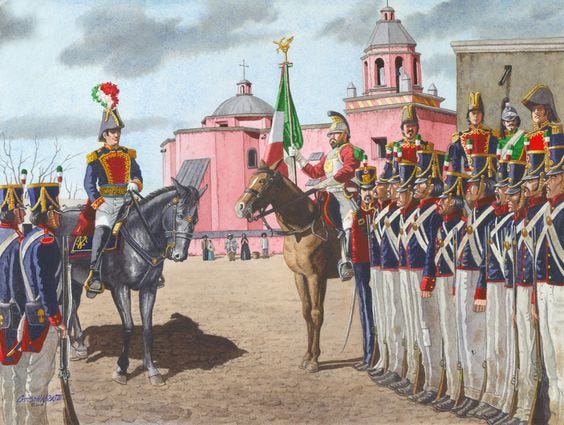

In 1823 Congress appointed territorial governors to the Californias who were sent back by the Californios. Fearing rebellion, Morelos asked Ignacio Lopez Rayon to take a thousand regulars to the Californias and determine the disposition of the Californios. Until 1823, communication and interaction between the Californias and Mexico has been minimal to nonexistent. The failed attempt to appoint governors coincided with the conflict in the Yucatan. Lopez Ignacio dealt with those territories during the war, and Morelos felt that he’d be a familiar face.

In February 8th 1824 Lopez Ignacio arranged a meeting of prominent Californios at San Diego de Alcala and was shocked to see the presence of several peninsulares, some of which were supposed to have evacuated years ago like the current (apparently) governor of Baja California, Jose Dario Arguello. Also, present was Dario’s Californio son, Luis Antonio Arguello. Lopez convinced the delegates from Baja California to “nominate” Dario’s son as the new governor of the territory promising them local control of most of their affairs as long as they didn’t act in a manner contrary to the national constitution. He also assured them that funds will continue to support the Presidios as well as eventual Mexican soldiers to help maintain the order.

As for Alta California, Jose Maria de Echeandia was put forth by Lopez as governor of Alta California with the same deal offered to the Alta Californios as the Baja Californios. Echeandia was at first an officer stationed in Sinaloa in charge of about 200 infantry men which served as an HQ of the presidios in the region that helped keep good and stable relations with the indigenous people. He was known to some of the Californios by name so they deemed him acceptable and agreed to “nominate” him too.

Having deemed his mission a success, Lopez wanted to tour the area in order to report back to Mexico City in person thereafter. He sent word that he would start in the north and move his way down to La Paz in Baja California where he hoped to board a ship of the Pacific Squadron back to Mexico proper. Along his tour he noted the deplorable conditions that the mission system left the natives. In a letter to his wife he lamented how the plight of the indigenous people in the Californias resembled that of those in the Valley of Mexico during Spanish rule.

Lopez’s wife, María Ana Martínez de Rulfo, had some of his letters published in Mexico City. One of them read:

“Querida, it is worse than I had feared. I praise the Lord every day that Hidalgo himself is not here to bare witness to the horrors that the indios face for his frail and aged heart would surely give out. What once was reported as large populations of indios has been withered down to a pitiful few by disease and outdated colonial practices that now have been outlawed by our great republic. The Peninsulares here still walk about as if they were Californias’ rightful rulers. In confidence several brave souls approached me and my men and recounted the abuses they faced. Beatings, slavery, neglect. The sick are left to their own devices and many Criollos and Mestizos are forced to do the bidding of their Peninsular masters. The Franciscans are accomplices to this travesty, their missions are, I fear, at the core of all of these ills. I must muster all my strength within me to maintain proper diplomatic demeaner before the barbarities of which my eyes are subjected to every day. The sights I have seen, it’s as if I was transported back in time to the days of De Las Casas. How I long to see your radiant face so that my eyes may be rejuvenated by your beauty and love”

This letter became widely published in Mexico City and around the neighboring states prompting liberals and the aging Hidalgo to react in Congress. By the time Lopez made it to La Paz in April 3rd, he received word of the Secularization act of 1824[1]. He was to transfer mission land into Ranch land grants modeled after the reforms in Central Mexico and the Yucatan. He was also to force elections for every position of power of which the Peninsulares were to be excluded from, and should any attempt to leave with their riches, he was to consider them enemies of the republic and have their properties confiscated. Lopez sent back word asking for reinforcements fearing that violence would break out.

When he returned to San Diego later that month, he met up with a young and vocal indio, Jose Pacomio Paqui. Lopez caught wind of a potential Indian uprising nearby and found out Pacomio’s role [2]. He had his messengers tell him that should he ally himself with the Mexican regulars, he would have the backing of the central government. Immediately, using assumed authority as emissary of president Morelos, he had Pacomio deputized as a commander of the Mexican army and told to organize his native Chumash battalions, a total of 3 were formed.

Alarmed at this development, Echeandia inquired as to the purpose of this sudden turn and was told about the Secularization act. Echeandia quickly realized the implications of such sudden changes so soon after instigating contact with Mexico. It meant that to the eyes of many in Alta and Baja California, Lopez would have to break his promise. Antonio found out by the time 500 cavalrymen arrived from Durango in late March bringing with them an artillery company. Lopez now had an army of over 3000 soldiers, a massive force when compared to the population of both Californias together. For the entire year Lopez was focused in enforcing the change. Together with Pacomio, he was able to defeat a few rogue elements in Califiornia that resisted, mainly Spanish soldiers and a few Criollos who were sympathetic to them. There were several units of foriegners who settled the californias, and to Lopez’s chargin, many of them came from the US, illegally. These soldiers also raised small armed bands to resist Lopez’s forces. After several weeks of fighting, most of them were either captured or chased away.

In May, the President officially appointed Echeandria and Antonio as governors and accepted the election results of new local officials. By August, Lopez finally was able to take his troops to La Paz and board ships to return home. The Californias have been tamed, and just in time for the arrival of over two thousand settlers from southern Mexico and Europe between December 1824 and June 1825. That wave would be followed by another three hundred settlers at the end of the year and a final wave under Morelos’ administration of seven hundred settlers in 1826. This caused California’s population to increase by nearly twenty percent within in two years reversing the trend of population decline in the previous decade. It also helped dilute voices calling for independence as the new settlers were marginally more loyal to Mexico City than to a Californian identity.

New Mexico

The New Mexicans managed to establish a prolonged peace with the Comanche Indians and were reluctant to accept the construction of new presidios in the area by the federal government. The Texans also had made a similar deal with the Comanche. This kept raids to a bare minimum which were not as devastating as they once were in the past.

At the beginning of Morelos’ term New Mexico had a population of around 29,000 New Mexicans plus ten thousand pueblo Indians a thousand or so others. The arrival of settlers from the south and Europe increased the population of non-natives in New Mexico to nearly 31,000 by 1826. Francisco Xavier Chávez was appointed governor by Morelos in 1822 to help manage the situation. Attempts to do away with the Cast system in the past had failed, Morelos hoped that Xavier’s Peninsular origins would help ease the transition away from the old Spanish system to that of republican equality, as Mexicans saw it at the time. However, he was caught up in the peninsular expulsion which led to New Mexican demands of autonomy.

Elections in 1825 placed Jose Antonio Vizcarra in the governorship of the territory running largely on the popularity of his military campaign against the Navajos. That experience made him valuable in the eyes of Mexico City in dealing with the natives in the region. Texan loyalty was ambiguous, and Mexico City saw New Mexico as a possible new state that would help bring the neighboring territories a greater sense of “Mexicanness”. Vizcarra gave a hopeful sign by asking for federal troops and the construction of presidios meant to deter retaliatory Navajo raids (a result of his military campaigns). Vizcarra began offering further avenues for Central Mexican influence in New Mexico. Eventually in 1826 construction of a road from Santa Fe to Durango began with the aims of establishing a continuous line of communication and further economic integration.

Texas

Throughout Morelos’ presidency, Anglo-American settlers (both legal and illegal) formed the largest block of the Texan population. This group identified more with the United States, their country of origin, than did with Mexico unlike other settler immigrant groups such as Italians, South Germans, and other Catholic Europeans. The second largest group were Mestizos from Central Mexico drawn by the offer of new opportunities and then followed by the Europeans and at the bottom Criollos. Peninsulares were expelled from the territory at the tail end of the war for independence unlike New Mexico and the California territories.

A problem of Anglo-American squatters began to emerge throughout the eastern and southern portions of Texas. Conflict arouse between legal immigrants from Europe and migrants from Southern Mexico with these squatters. Stephen Austin asked for permission to raise a militia to maintain the peace, but instead Morelos mobilized the Coahuila state Militia and the federal garrison in Monterrey to march north and begin policing operations. Austin wanted to set up an arbitration committee and find compromises with the various groups. However, the Mexican government would not concede anything to squatters after word of their ownership of slaves reached Mexico City. In 1824, the Mexican military arrived led by Juan Davis Bradburn and began working with Austin to remove squatters and free slaves. Austin attempted to argue that squatters should not have their “property” confiscated only to be reminded that in Mexico, people weren’t property.

Several Squatters began to take arms and organized bands known as “Texas Rangers” and attacked Mexican soldiers. It didn’t take long for the army to discover where the Texas Rangers were getting their weapons from. As it turned out, many of the squatters were financially supported by individuals like Andrew Jackson and Sam Houston back in the United States. Mexican Spies in New Orleans also brought back information confirming Jackson’s involvement who at the time was a senator to the US Congress. Mexico filed a formal protest in Washington to which President Monroe responded accusing Jackson of attempting another intervention that, as he put it, “Would prove as disastrous as the last and only further validate [Jackson’s] own ineptitude as a pitiful Napoleon acolyte”. Monroe used this as an opportunity to take another shot at Jackson by pushing the senate to censure him, which they did in early 1825 leaving an infuriated and politically diminished Jackson who ended up leaving the senate later that year[3].

As a result of these developments, Morelos ordered the expulsion of any Anglo-American squatters who did not convert to Catholicism, release any and all slaves, and begin learning Spanish. Austin managed to convince local officers of the military to interpret this to mean that squatters that did conform to these requirements could keep their land. By 1826 fighting involving the squatters diminished after a few major skirmishes related to the expulsions. Andrew Jackson and Sam Houston began plotting a solution to what Jackson termed “A grievous injustice from a barbaric government that does not respect the right to private property. The Lord will see to it that just retribution shall be visited upon these mongrels,” promising to right the wrongs done against his countrymen. At first, he planned on winning the next elections, as he came close to wining in 1824. But after losing them he would end up supporting the Anahuac revolt in Texas in 1832.

By 1826, Texas lost some 300 Anglo-Americans through expulsions who were replaced by a new wave of European and Mestizo immigrants that more than doubled that number.

-----------------------------------

[1] Happened later in the OTL

[2] OTL leader of an Indian revolt in that period.

[3] He did end his Senatorial term in 1825 in the OTL, but not with a bloody nose like this.