I had to take an unexpected break for the past few weeks. Unfortunately I won't be able to post as often as I would have liked but here is the latest update. The war will continue after this.

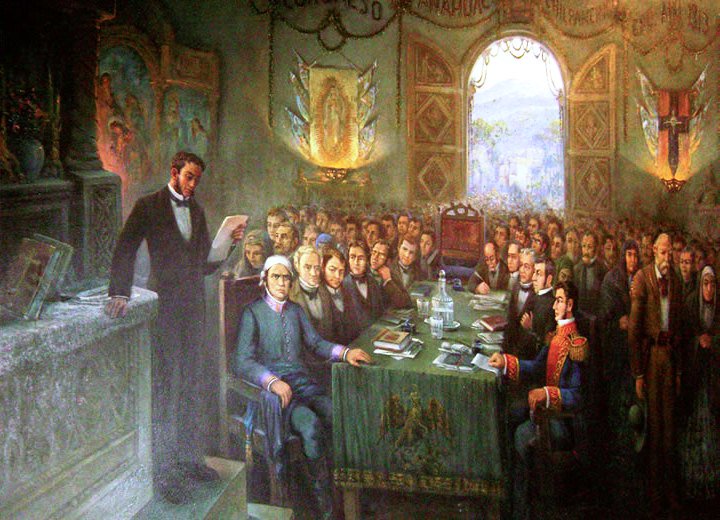

Part 2: The War for Independence

Dramatization 1: The Changing Winds

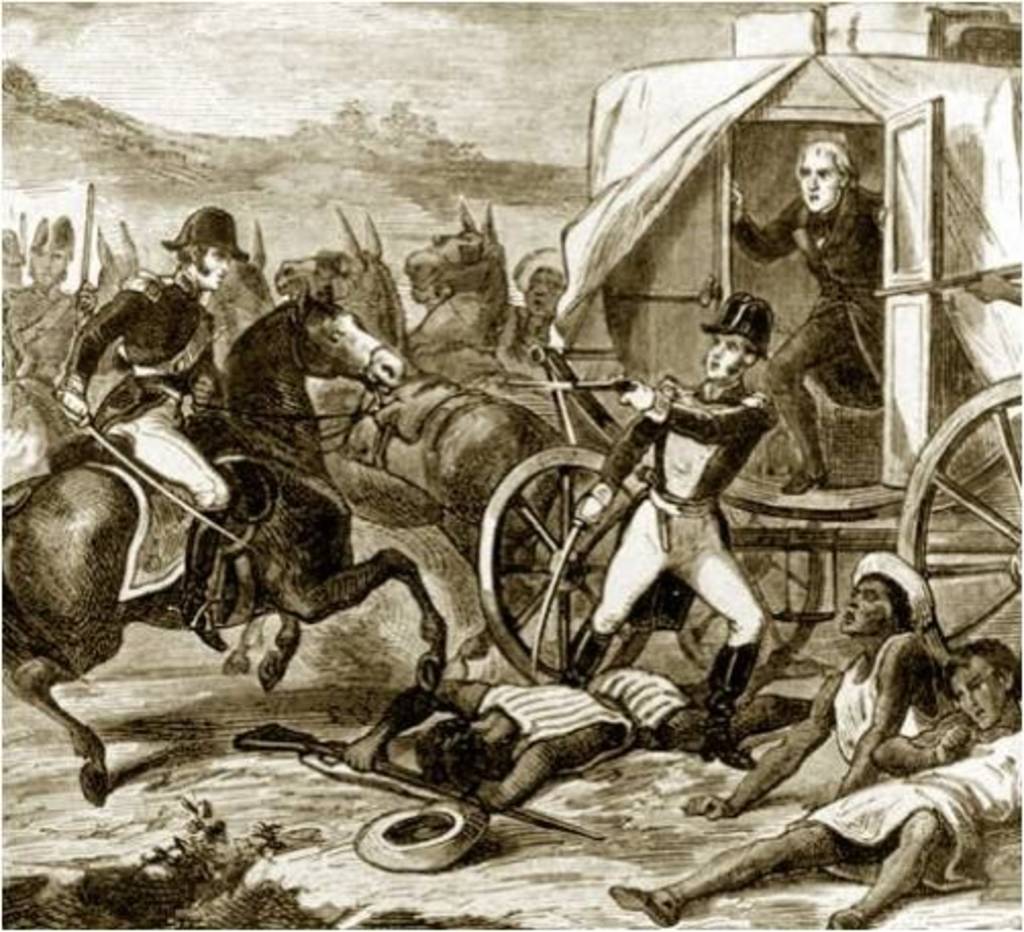

The moment after the battle of Monte de las Cruces was pivotal for the course of the war. Hidalgo, the de facto leader of the insurgency at this point, entered in fierce debates with Allende over strategy and the unruly nature of the untrained militia that joined the insurgent forces after the Cry of Dolores. Before the battle of Monte de las Cruces Hidalgo and Allende argued regarding the role that the indigenous troops were to play the coming battle. After the stunning defeat of the Royalist army, the two men would argue over whether or not to proceed to Mexico City or head north, a path that the doomed Aldama and eventually would take the bulk of the untrained militia force.

Ignacio Allende entered the meeting tent where the Father Hidalgo sat. The father exhaled and rose extending a hand which Ignacio grasped, each other's eyes met for a moment where time seemed to pause. Both men knew what would be said, and both men knew why. Ignacio paused and waited for Hidalgo out of respect for the man who was responsible for the movement's popular support. Ignacio always respected the priest, but the past few weeks did much to distance the two.

"

Capitan," Hidalgo said at last and smiled looking around the tent at the two other men in the room, each of them indios.

“We’ll move north soon,” Hidalgo continued, “Mexico City will have to wait.”

Ignacio took in a deep breath and began to speak, but one of the other men spoke up first. A medium height man dressed in all white fabrics, indigenous with long hair and dark eyes. Ignacio didn't know him, which meant he was one of the irregulars that joined after the outbreak of hostilities.

"

Capitan," he spoke with an accented Spanish, "We are quick learners. We will train with your men."

Hidalgo smiled placing his hand on the man's shoulder and responded, "We need to regroup and work on training the thousands who have joined our movement before we attack the capital.”

"

Cura," Ignacio spoke slowly staring at the man, "The unorganized militia shouldn't join us in anymore battles, much less move through Royalist territory."

"This is our fight!" another

indio stepped forward, shorter than the first but fierce in his determination.

"They have proven unable to follow orders," Ignacio continued, "their unruly behavior even contaminates the trained indios. We took heavy losses because…"

"No no no no," Hidalgo inturrupted, "

Los Indios have lived too long oppressed by the Spaniards. They came to fight for themselves, for their homes."

"If I am to command our forces, this is my call," Allende spoke and turned to the second man then back at Hidalgo, "This war is for capable men to fight, for soldiers, not mobs. We can’t stop at the door of victory just to include men who have proven themselves incapable of civilized war."

"This war is for their freedom" Hidalgo began raising his voice, "You know this. If they don't fight no one will take them seriously. No one will remember their role in this war and continue to take and take from them treating them like animals!"

"I understand

Señor cura," Ignacio said, "but they are uneducated, uncultured..."

"You speak like the Spanish," The first man said, "This is our land."

"It's my home too!" Ignacio shouted, “And Mexico City is defenseless, we have to move against it now”

"We've all been wronged by the same people," Juan Aldama said as he walked up behind Ignacio, "

El Capitan knows this. He's just being cautious and wants avoid needless loss of life through looting."

"We take what belongs to us,” The man responded.

"I know," Hidalgo responded, "And the Criollos should know this too. This is their fight, and they will all join. But the fight for the city won’t be today."

Hidalgo made his way out of the meeting tent with Ignacio right after him calling, "

Señor cura!!"

The two men passed a few other tents in the camp before Hidalgo stopped and turned. The wind began to pick up, Ignacio looked around and pointed at the soldiers with blue and red uniforms huddled in groups. Several men on their way to relieve sentries in the perimeter of the camp passed them both heading off to the distance past a group of indios sharpening their machetes, their only weapons. So many indios had joined the army that not enough weapons were made available, and even if they were Ignacio was not convinced they'd be of much use to them. Most of the

indios were field laborers who never touched a firearm in their lives. With the sun shining through the clouds, he took in the all too familiar dark copper toned skin, a pretext for dividing the people of the new world. He couldn't help but feel guilty at dismissing them, but he couldn't allow their inexperience to sabotage any chance at victory. It wasn't about them being

indios, it was about them not being trained, he told himself.

"This," Ignacio said, "this is about winning, not about some symbolic gesture. These

indios will have their chance when they are better trained better disciplined."

"That’s exactly why we can’t attack now,” Hidalgo responded, "But they should be part of the attack when it happens. They have waited so long for freedom"

"Freedom? Those

Indios know nothing of freedom! They are ignorant men with machetes!" Ignacio regretted the words the moment they left his mouth.

"

Perdóname," Ignacio apologized, "You know that I too wish to see their dignity returned to them, an end to the

Castas system, to the tribute, to the abuse."

"Then let them take their dignity back," Hidalgo said, "That's why they want to fight. For too long they have been ignored. Have you seen what the trained militia look like? How many

indios are in them?

"

"Training too many

indios would have aroused too much suspicion," Ignacio responded.

"

Lo sé," Hidalgo agreed, "but don't you see? If they don't take their dignity back now, they never will. If the army of their liberation is formed by the castas and Criollos, they will be nothing more than passive participants forgotten by all. It's their time to return to what they once were."

"

Está bien Padre," Ignacio responded, "They'll fight in this war, but the ones we trained. Right now, we need to take the city. If we miss this opportunity, everything will end."

"We can’t, we’re not ready” Hidalgo replied.

“You’re not ready” Ignacio spat back, “I know you’re afraid that you can’t control them. You’re afraid that they are going to lose control. They’ve done it already, and that’s why you have to keep them out of the fight” Hidalgo responded, “They all look up to you. Without you they won’t follow.”

“I can’t” Hidalgo said.

“Send the undrained

indios North with Aldama,” Ignacio said, “He can take two thousand regulars to train them and lead them to assist insurgents in the north. That’ll leave the twelve thousand trained militiamen and five thousand regulars with me to take the city.”

Hidalgo stood silently as Ignacio continued.

“They’ll do as you say, but if you don’t then I am going my way and this movement falls apart.”

Hidalgo stood and looked over to the north and the east and said, “You always wanted me to get rid of them.”

“

Por Dios!” Ignacio grew tired, “

Señor Cura, we can not fight this war with this populous rabble!”

“Enough!” Hidalgo shouted as the breeze changed direction, “Tell Aldama to prepare to move as you said. I’ll lead the militiamen with you into the city.”

“Thank you,” Ignacio said relieved. After returning to the others they hatched out their plans to attack Mexico City.