1634: With this Shield, or on it

[Here is the edited update. It should cover most of the earlier reader responses. Those that weren't, I will respond to at a later time. Updates to the original are mostly concentrated around Skoupoi and at the end of the Twelve Days, but there are edits throughout pretty much every part of the update, except for the very final scene. Patreon post will be updated with a corrected link once this goes up.]

To help counter that, and to combat the reported new and improved Triune artillery train, he has pulled together cannons from gun parks throughout Europe to reinforce his own. His gun line is twice as big as it was a year ago. Blucher’s grand batteries won’t have much luck with that. The downside of that is the slower pace of the army.

He probes toward Vidin, moving cautiously so as to avoid any ambushes. In the smaller skirmishing around Vidin at the end of last year, both sides showed an ability to play that game. And considering his large and necessary artillery train, he wants to avoid the fate of Stefanos Monomakos, who during the Great Uprising saw most of his artillery train destroyed by an Idwait ambush, ruining the Roman offensive for the year.

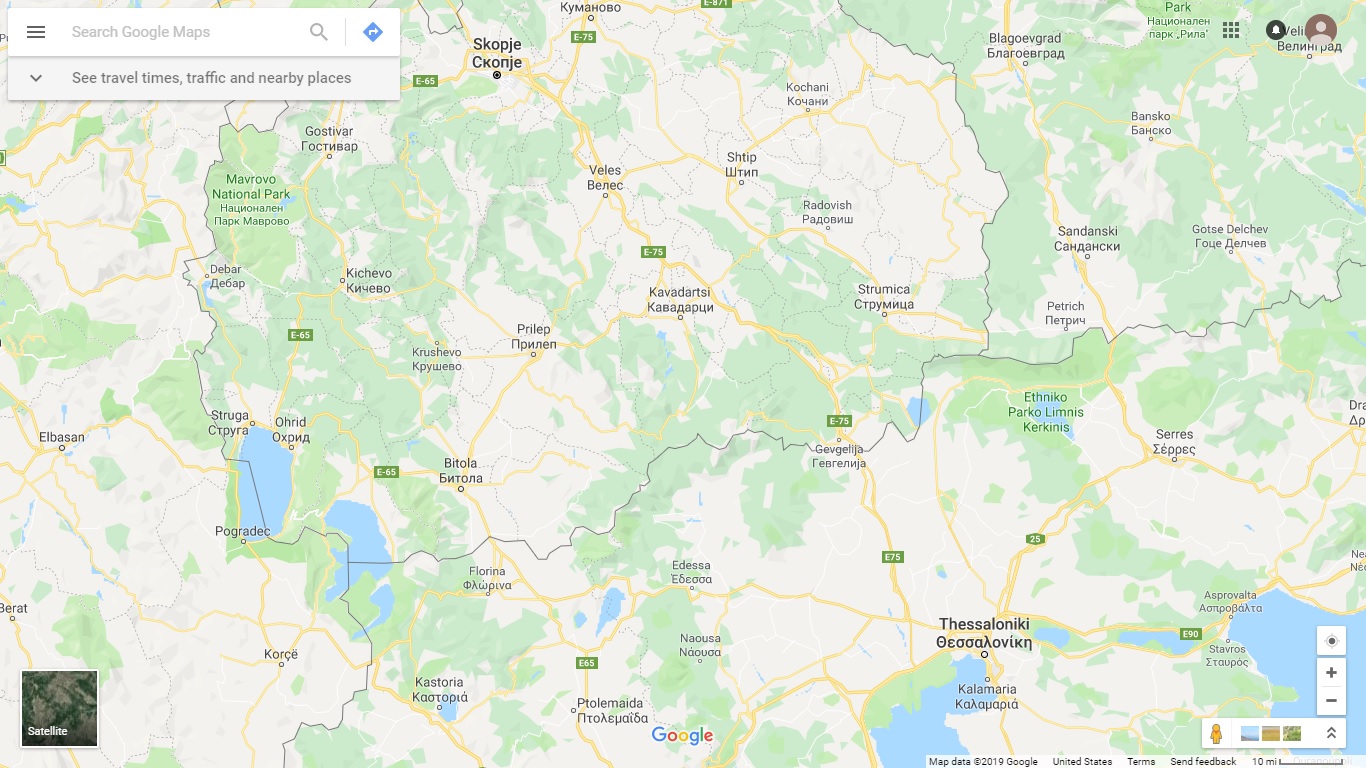

And so he is caught completely off-guard and well out of position when Blucher’s army of slightly over 80,000 storms across the border and assaults Skopje, in the upper Axios River valley.

Demetrios III had expected something like this to happen. He’d argued during the winter that something like this would be entirely in keeping with Theodor’s nature. However he left the decision in the hands of his Domestikoi, and they’d disagreed, expecting Blucher to play a hard defensive campaign around Vidin/Belgrade. Demetrios had not ordered them to guard against this, but his attempts at convincing them had mainly served to make the Megas Domestikos and the Domestikos of the West more convinced in their own opinion. Demetrios III is their Emperor and a good administrator, but they know as well as he that he is no soldier.

There had been some reports in Serbia (the information is sparser now that Blucher is mainly operating in non-Roman territories) that suggested a southward movement but Michael had dismissed them as misinformation to distract him. Helping to push that narrative is Despot Lazar, who is rather put out by Demetrios’ recognition of his younger brother as King of Serbia. Now his wagon is truly hitched to Theodor’s train. With experience of how Romans operate, he captured a couple of Roman spies during the winter and turned them, whether by threats or bribes is unknown, using them to feed false information to Michael that ‘confirm’ that the real preparations for a southward advance are truly a feint.

By this point Michael is starting to set up his first parallels around Vidin, entrenching his artillery and growing concerned about Blucher’s absence. The news is delayed in reaching him as due to bad weather the semaphore line from Thessaloniki to Constantinople wasn’t able to operate but he immediately breaks camp with the bulk of his army to march to Skopje’s relief. He leaves behind a portion though to siege Vidin, including the bulk of his amassed artillery and all of the heavy pieces.

The leaving of the artillery is a gamble, substantially weakening his army, but he has to do so if he wishes to move fast. He’s still marching with an array of field pieces which can keep up, but not in the numbers he’d gathered over the winter. To move his guns and supply wagons more quickly he needs more teams of horses, and he only has so many of those to go around. Therefore many cannons have to be left at Vidin in the name of speed. Some of the losses though can be made good by pulling from the reserve guns and mounts stabled at the Serdica Kastron. That all said, the batteries he still commands would be impressive…until compared to that of the Triune train, twice the size of last year’s. Henri II, for his part, also wants to send a reminder to Rhomania of the Triple Monarchy’s power.

But leaving Vauban unmolested at Skopje is not, in Michael’s view, an option, after seeing the devastation wrought along the south bank of the Danube in Bulgaria and hearing reports about Upper Macedonia. Skopje, along with Ohrid, were the two key citadels that kept the Allies locked into Upper Macedonia (except from some raids). If Skopje falls, Blucher has a clear shot straight down the Axios River valley which leads into Lower Macedonia.

The region has a well-developed and maintained road network and Lower Macedonia, once one gets into the coastal plains, is per-capita possibly the richest region in the entire Roman Empire. The Macedonian theme has 2.4 million inhabitants, second only to Thrakesia, and includes Thessaloniki, the second city of the Empire. It is more than capable of sustaining even the Allied host for a campaign season, and there’s no telling the moment of damage they could cause in the meantime. But if Michael can halt the Allies while they’re still in the mountainous uplands and hold them up, they’ll either starve or be forced to retreat. However for that to happen, Michael absolutely has to move fast.

Skopje is the third largest city in the Macedonian theme after Thessaloniki (170,000) and Dyrrachion (60,000) with a pre-war population of 35,000, although refugees from parts of Upper Macedonia doubled it at one point. Some have moved on to Lower Macedonia or further afield, but many remained in the city. There was war work available, the garrison here provided good protection against Allied raiders, and many could also be supported by family relations in the hopes of returning soon to their lost lands. Before the Allied onslaught, some of the inhabitants of the outlying villages manage to flee to the city, boosting its population back up to 60000.

The city is known as Skoupoi [1] to its Greek-speaking inhabitants. It has modern defenses, but their size and sophistication are not that impressive. It was taken by the Hungarians and then recaptured by the Romans during the Mohacs Wars, neither side having any serious difficulty. Given the expense of building top-notch modern fortifications, the money was never available to do more. The Danube and eastern citadels were what sucked up the budget for kastron-building.

Where money was spent was on the transportation infrastructure of the region. The old Via Militaris runs through Skoupoi southward to intersect with the Via Egnatia near Thessaloniki. It’s been refurbished and expanded, paralleled by the ‘Ore Road’, a new construction from the Flowering, built to ease the transportation of produce and livestock (despite the unofficial name) to Thessaloniki’s demanding markets.

There’s much work on the Axios itself from the Flowering as well. Much is for flood control, but also to make the river useful for flat-bottom barges to carry loads of timber and ores from the mountains to the foundries and workshops of Thessaloniki. This parallels other riverine works in the Empire both for flood control and to improve navigation, primarily on the Meander and Halys Rivers in Anatolia. Other works are to facilitate the use of water power for various tasks; the mill that gave the battle of Miller’s Ford in the War of the Rivers its name was one of these.

Blucher hits Skoupoi fast and hard, knowing that he cannot afford to be stuck in the mountains for long. Wagon trains are coming down the Via Militaris from Belgrade, but that’s a far cry from the Danube. They can provide him with the shot and powder he needs; Blucher absolutely wants to avoid the lack-of-powder nightmare from last year. But to feed his army, he needs to get to Lower Macedonia fast.

Vauban is well aware of this. Historians debate how privy Vauban is to his master’s plans regarding Emperor Theodor, but no one can doubt that he did, and does, his utmost throughout his assignment with the Allied army. The simplest explanation for that is a victorious Roman army may end with one Marshal Vauban being made dead in the process.

So he is much more aggressive here. His tactics are normally methodical and inexorable, with minimal risk to the besiegers, but at the cost of being slower. That’s not an option here so he pushes his men, digging their parallels closer and working the guns to smash the Skoupoi defenses flat.

The men know this too so they also work harder. Yet despite their situation there are few desertions. Partly there is the example of last year, where those who deserted ended up being blasted from the mouths of cannons, while those who stayed with the standards had a chance to live. While Lazar is cooperating with Theodor (although Blucher pointedly makes sure to keep the Despot far away from a battlefield command) individual Allied soldiers still stand a good chance of being bushwhacked by Serbian peasants, for their boots if nothing else. The only difference from Rhomania is that their body will be dumped in a hidden hole rather than mutilated and left in public view.

There are also the Roman partisans from Upper Macedonia. To reinforce his lines, Blucher has pulled the bulk of his troops from the occupied regions of Macedonia save those masking the Ohrid garrison. Unfortunately they are followed by the partisans, whose regular source of supplies has been raiding the Allied garrisons and now come in their wake.

The most dangerous are the two bands of ‘commune partisans’. These are from two small districts that were never occupied, or at least never secured, by Allied forces. The locals in those districts set up little Roman enclaves, organizing their defenses and electing leaders and officials, typically through the preexisting village framework. Because of their small and isolated natures and no possibility of trade (although there was some smuggling, sometimes with the connivance of the garrisons) raiding is essential for their survival. And so the fighting men of the communes followed.

There is also a much smaller third band, which extorted some supplies from Allied garrisons by threatening them with cannibalism. Despite its few members, this force has become quite a bogeyman to Allied troops for that reason. Historians of the period mostly think the cannibalism was merely a creative threat to compensate for the force’s weakness, rather than something actually practiced, although a minority think it was at least practiced at a dark moment to give the future threats some teeth. More than a few of those historians have commented that in Demetrios III’s detailed history, which does discuss this band, he is uncharacteristically silent in this matter.

The city’s garrison is commanded by Kastrophylax Andronikos Laurentios but the heart of the resistance to the Allied siege is Konstantinos Mauromanikos, the Bishop of Skoupoi (and first cousin to the commander of the Army of Georgia). During the Council of Constantinople in 1619, he’d argued that suicide was valid, even commendable, if a member of the faithful was faced with Latin rule. This was voted down but he brings a spirit of fanatical resistance to the defense. Yet while fervor is useful, it doesn’t slow cannonballs.

A pair of storm-able breaches are smashed through the walls on the north side, although the gun crews take heavy losses from sniper fire in the process. To boost morale and encourage volunteers, von Mackensen christens those batteries as ‘men without fear’. [2] The guns are never short of volunteers. A demand for surrender is denied and Blucher orders his men to storm the city on May 14. It will be bloody but he can’t afford to wait.

At that time, 80% of the city is north of the Axios, dominated by the Fort of Justinian [3], built by Justinian well over a thousand years ago. It has been repaired and expanded some since then, but it is still a pre-gunpowder fortification. The city south of the Axios is connected to the north city by a great stone bridge constructed near the end of Andreas I’s reign, which is overlooked and dominated by said Fort. [4]

Fighting is utterly savage in the way only house-by-house urban fighting can be. Battle is waged with every weapon and resource and person who can be brought to bear. It takes two hours for the Allies just to clear the Church of the Ascension of Jesus Christ, with soldiers from both sides firing on each other along the nave.

Spanish painting-The Last Defenders of the Church of the Ascension

[By Joaquín Sorolla - Museo del Prado, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=76135129]

One of the many heroes on the Roman side in the defense is a young woman named Anastasia, the Maid of Skoupoi. While bringing up supplies to one of the barricades, she saw the last of the defenders killed. With the one cannon there already loaded, she fired it into the ranks of oncoming Bavarian troops, so close that one was able to touch the barrel as she fired the double-Vlach shot into their ranks. The carnage drove them back long enough for reinforcements to arrive and secure the barricade.

A Spanish painting of Anastasia of Skoupoi.

[By David Wilkie - Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5763200]

It is not war to the knife; it is war to the teeth. Sometimes there are firefights waged between forces in houses and shops on opposite sides of the street from each other. After five days of fighting the Allies have taken two-thirds of the north city, with the price of thirty five hundred casualties. The Roman regulars and the local allagion (militia force) have some training, which help in handling the carnage. But most of the Roman defenders, who are mostly untrained civilians and have taken over fifteen thousand casualties, have had no such preparation.

It is an absolute nightmare, of steel and blood and screams, of young boys pleading for their mothers, screaming that they don’t want to die. Of piles of shattered limbs, of gorging ravens too fat to fly waddling through the abattoir, tatters of bowels hanging from their beaks. This isn’t Skoupoi. This isn’t Earth.

This is Hell.

The people of Skoupoi have taken it for five eternities, five eons of horror. But the human body is not meant to take this, and as slaughter drags on and the nightmare seems to show no signs of ending, they begin to crack. In one street a party is held where people, in the middle of a firefight, start guzzling liquor and placing bets on which of them will die first. “Happy is he who is picked to lead.” In another outbreak of madness, or celebration of life, depending on one’s view, people dance and sing together amidst the fire, trying to remember what life was like before the horror, until happy merciful death comes and releases them from here.

The morale, the sanity, of the people of Skoupoi is falling to pieces, even as they continue to fight and die. Some charge the Allied guns, with no other purpose than to end it already, for not one more minute of this place can be endured. Not one more minute. Not. One. More.

That it lasts this long is due to Bishop Mauromanikos. He is everywhere, pleading, cajoling, inspiring, haranguing, using every tool he can think of to encourage his flock, to get them to last just a little bit longer. To do so, because he has to, he puts himself into incredible danger to inspire them. On at least sixteen different occasions, he stands atop barricades loudly praying for the people of Skoupoi as bullets whip around him, killing his assistants who willingly accompany him, punching through his vestments, and even trimming his beard. And yet he is unharmed, but every minute he lives is a miracle.

On May 19 the Roman Army of the Danube arrives, making the 400km march (as the most direct road goes) in ten days once they broke camp at Vidin. Michael’s initial plan had been to swing west, find some hills dominating the Via Militaris north of Skoupoi, and entrench, forcing Blucher to either attack him there or starve. But then scouts reported that the walls of Skoupoi had been breached and the city taken.

In that case, Michael’s previous strategy would be even worse than pointless. If Blucher has Skoupoi, then he can surge south into Lower Macedonia, where supply lines aren’t necessary. Without a thorough stripping of the countryside beforehand, which isn’t likely unless Michael can at least slow him down, the area can supply Blucher with all the food, fodder, powder, and shot he needs at least through the autumn. And Michael can’t slow him down if he’s entrenched on some hill in southern Serbia.

Scrambling in the opposite direction, Michael drives to swing around and cut off Blucher somewhere in the mountains before he can break out into Lower Macedonia. If he succeeds, the capture of Skoupoi will be irrelevant.

While force-marching at an even faster clip, having to leave behind some of his heavier field batteries behind to maintain speed, he gets improved information. Skoupoi hasn’t fallen, but is instead in a massive street battle, fighting hard but losing ground rapidly. By this point the Army of the Danube is at a point where it’d take longer to reenact Michael’s original plan rather than march directly to Skoupoi’s relief. The army can either do battle at Skoupoi itself, likely in terrain of Blucher’s choosing, or try the initial plan, which runs the serious risk of not getting placed quickly enough to stop Blucher surging down into Lower Macedonia. Except this time, Michael will have worn out his army with repeated force marches and not be able to interpose himself in time.

Another option is to let Skoupoi fall and take up a blocking position south. But to leave the people there to die after fighting so valiantly just seems wrong. The Army of the Danube and Michael Laskaris have had to do that too many times already, and they’ve seen the destruction wrought by the Latins after they’ve done so. And they are sick and tired of it. No more. Not this time. The army will march on Skoupoi.

A flying column though is sent back north to at least partly reenact the original plan, although this is an ad-hoc structure rather than the original troops that Michael would’ve used for a flying column. Those, having been sent on ahead during the march south to find a good blocking position, would have to march back even further. The original flying column proceeds to Skoupoi, probing the Allied defenses, and getting beaten back for its troubles. The initial sight inspires hope amongst the Skoupoi defenders, which is crushed all the more when the Roman regulars have to retreat out of sight, linking up with the main army.

Meanwhile, in a moment of rage at the updated report, which if he’d gotten a few days earlier would’ve made a world of difference, Michael whips his horse into a gallop, going on a furious ride to blow off steam outside camp. His horse trips and falls, seriously injuring the Domestikos who is coughing up blood at the end of the day. Taking himself off active duty, he is succeeded by the senior strategos Hektor Likardites, he who told a younger Athena Siderina that women can’t face cold steel. However despite his injuries, Laskaris stays with the army as a sort of advisor.

Hektor approaches Skoupoi from the south, despite the extra delay that imposes. Considering the comparatively weak artillery currently at his disposal despite the pieces pulled from the Serdica kastron and the nose-bludgeoning the flying column got, he does not care for attacking the well-built field fortifications guarding the Allied northern line. But the lines on the south side are weaker. If he can smash through there and reinforce the north, he can then drive the Allies out of the city. Once properly garrisoned by the Army of the Danube, there is no way Blucher can take Skoupoi, Vauban or not, and he’ll have to either retreat or starve.

“What, what is that?” the people of Skoupoi ask as the banners crest the horizon. There is something else out there beyond the inferno? There is a possibility of actually surviving this? There is…hope?

The Romans crash into the southern Allied lines, scattering most of them like tenpins, but then they run into an understrength regiment of Saxon veterans, who’ve received a personal hand-written appeal rushed from Blucher himself to hold the Romans as long as possible and to the last man. And for Old Man Blucher, they will. Slamming a musket volley into the Romans’ faces at two meters’ range, the Roman advance stalls.

Is this all just a cruel hoax? Is this hope to be snatched away as quickly as it came, more cruel than if it had never been, just like the first time? Rationality would say the delay, for all the Saxons’ skill, will only be a few minutes, but rationality, sanity, has no place in Skoupoi, and not one more minute can be endured. The last thread frays.

Bishop Mauromanikos pleads with his flock to endure, for just one more moment, and then this cup of woe will pass from them. Just a few more minutes, he argues, but it is hard, for not one more minute.

And then there are no more miracles for Bishop Mauromanikos. A Bohemian cannonball hits him in the chest, disintegrating his torso and sending his blood spraying on his horrified flock, his severed limps flopping to the ground.

Not.

One.

More.

The last thread breaks.

It starts as a trickle, but the avalanche only needs one pebble to begin. The first person to run gives a license to all those who have been wanting to flee for so long. It soon it turns into a flood, despite the efforts of the still-fighting regulars and militia to keep them. They flee the barricades, flying back towards the Roman troops that by this point have overrun the Saxons and are pouring across the Stone Bridge. But that doesn’t matter anymore. Nothing matters. Not God, not Rhomania, not city, not love, not family. Nothing matters except No More. They just cannot take it anymore. And so they flee, seeking the one escape to the hell that has become their life, the overpowering cocktail of fear, panic, and madness blinding them to all consequence or reasons.

The regular troops, who had at least some preparation for all this in training, that make up the proper garrison stand to their defenses, but now they are horribly outnumbered and soon engulfed as Blucher throws in everything he has in a do-or-die assault. The Kastrophylax is killed trying to hold the medieval gatehouse of the Justinian Fortress, the Allied assault commanded personally by von Mackensen, two bullets punching through his bear-skin cap, although he is unharmed.

Meanwhile the inhabitants of Skoupoi are now crashing into the columns of Roman troops, snarling them in a horrific traffic jam. Panic spikes even more amidst the civilians, their courage shattered by the last five days of battle as they push and shove frantically to get south of the river, behind the ranks of Roman soldiers. Except in their panic they’re making it all the harder for those soldiers to get in front of them; in their desperation even the flats of swords and ambrolars can’t stop them.

The only thing that would make them stand aside in their state would be for the Roman soldiers to open fire on their own civilians, and that they will not do. The pre-war Roman army might have; that one was more select, filled mostly with long-term volunteers who’re making the soldier career their life. The war army still has those, but also tens of thousands of conscripted civilian ‘soldiers for the duration’ or militiamen inducted into the army. The mad-with-terror people in front of them, filled with women, children, and old men, (who had originally volunteered to fight on the barricades to protect the many more huddling in terror in the south city) are their wives and sisters, mothers and daughters, sons and gray-bearded fathers. One Roman tourmarch in his frustration does order his men to fire on them; he is promptly informed by his first dekarchos (who is from a small village north of Skoupoi) that if he really wants that order, the dekarchos will kill him on the stop. The soldiers do not fire.

And then the guns of the Fort of Justinian open up on them. The defenders spiked half of them before they were killed, although some of their wrecking work could be quickly repaired. But that still leaves half of the guns clear for action. During the urban battle, the guns of the Triune artillery train had mostly kept them down, but even so those cannons had afflicted heavy losses on the Allied assault troops. But now they are clear, the Bohemian gunners presented with the target of their dreams.

It is impossible for any shot to miss, each ball carving bloody swathes through ranks of dozens of bodies. Three-story buildings on either side are splashed crimson to their rooftops by the slaughter.

The Roman soldiers immediately start retreating under the hail, keeping good order despite the carnage, although some of the newest units are shaky. But if the civilians were panicked before, now they are almost deranged with fear. Trampling each other, they pile into the Roman soldiers again, trying to beat their way through, again tangling them as the Allied guns pour shot after shot into the massed ranks.

The gunners also started with the square at the north end of the Stone Bridge, working their way northward as some of the Roman guns are repaired and brought back into action as some Triune guns are hauled up to bolster them. Those fleeing have to clamber over piles of shattered dead.

Likardites is aghast at the slaughter of his forward units. Trying to throw more troops in there will only further congest the area and the Allied guns by this point are now shelling the Stone Bridge, the misses killing some of the few who seek to escape by swimming the Axios. For most, including the Roman soldiers who unlike the navy don’t have a swimming requirement, that is not an option.

Instead he brings what guns he has to bear. But he only has light field pieces plus a few heavily outnumbered larger cannons from Serdica. With the buildings of the south part of Skoupoi obstructing firing lanes, the pieces have to deploy along the south bank of the Axios, easy targets for the Fortress guns, and at their range and angle the light pieces lack the punch even against the Fort of Justinian’s obsolete walls. First to go into action in the rush, three-pounders with no protection firing upward at protected twelve and twenty-five pounders is not a contest. One Roman cannon is smashed in less than three minutes. Three batteries have their ready and reserve crews completely wiped out. Yet there is no need to call these batteries ‘men without fear’. Volunteers come forward to man and die at the guns, trying to cover their comrades and ‘families’ trying to get to the south bank.

A pair of eight-pounder and a twelve-pounder battery get into action, and these are strong enough to smash three former Roman cannon and three Bohemian or Triune guns on the wall to pieces, killing half of their current crews. But the Allies have numbers and elevation on their side, and send shot whistling down to wreak carnage of their own on the new Roman batteries.

The Romans try, but despite their sacrifice they mostly fail. With Allied troops hurling musket fire into them now as well, few can escape the cauldron. And some of the Roman soldiers, veterans of last year’s campaign, as they die, turn their heads toward Constantinople and scream “Are you satisfied?! Have enough of us died for you?!”

Others do escape, flying across the Stone Bridge, hotly pursued by Allied troops. Roman cannon and musket fire flay those pursuers, sending them screaming back to the north side. But then they regroup, supported by the Fortress guns and more Allied artillery being set up along the north bank. With the Roman pieces battered by the Fort, the contest is again unequal.

Aside from that, Likardites now has even more civilians on his hand. Aside from those in the north who managed to make it clear of the abattoir, there are those that were originally in the south city when the Romans arrive, who make up the bulk of the city’s population anyway. And those southern civilians are catching the panic from their northern counterparts. Unsurprisingly families are not inclined to calm when they see their screaming half-mad covered-in-blood husband/father.

On the north side it was something like ten thousand jamming the roads. Now there are forty thousand, in a smaller space, trying to flee out of the city and snarling up Roman troops trying to set up barricades. Some of the Allied pieces along the river have clear sights on the traffic jams and start reaping a harvest of their own, albeit one not quite as gruesome as on the north side.

Considering his position untenable, Likardites begins withdrawing from the south city, although the troops at least retire orderly, either taking away or spiking (more thoroughly) the guns on the south ramparts of Skoupoi. He sets up camp just out of cannon-range of the south wall, trying to restore some order amongst the now-refugees. Blucher meanwhile occupies the south city.

Both sides have been heavily battered by the fighting, although the casualties of soldiers at Skoupoi are roughly equal, but now the Roman soldiers are outnumbered by about 8000. The Allies started the campaign with fewer soldiers, but there is a Roman detachment still besieging Vidin plus the now-pointless northern flying column. Plus Likardites has 40,000 refugees on his hands. And he is on the wrong side of the river.

If Likardites can still hold Blucher up in the mountains just for a fortnight, maybe even just a week, even the loss of Skoupoi may prove irrelevant. But the Axios curves downstream, its south bank becoming its west bank and its north bank its east bank, and Thessaloniki and Constantinople are both east of the river. He cannot stay here. As Blucher works down the river, Likardites moves as well, the refugees dragging on him like an anchor. Yet not all the Romans go with him.

South of Skoupoi, Upper Macedonia, May 20, 1634:

Domestikos of the West Michael Laskaris looked to the north, to the battered smoking husk of Skoupoi, and to the four Bavarian soldiers watching him, their hands on their muskets. He sat on a chair, some wine and opium-laced kaffos on an army chest next to him. He really needed those, taking a drink of the now-lukewarm kaffos.

He coughed into a handkerchief, pulling the white fabric back to see several flecks of blood now there. He coughed again, adding some more, then adjusted his very baggy coat.

He was sick, and he looked it. He was in no shape to stay with the army, even as an advisor, with the hard fighting and marching that was to come. He probably shouldn’t have stayed with the army at all after removing himself as commander, but he’d not wanted to go back to Constantinople.

And that had not changed. He had absolutely no intention of returning to the capital, like this. He might recover from his injuries. He might not, but either way Constantinople was not an option.

He expected to be called back to the capital, which was partly why he’d stayed on as an advisor, even though that was not expected of him. Likardites was his second already; he knew everything already.

The Emperor was a reasonable man though. It wouldn’t be like Gabras. If he was to be damned, then he would damned for what he deserved. And he did deserve to be damned, he admitted. He’d planned for what he expected to happen, but not for what he did not expect to happen, a cardinal error. And so when Blucher had upended the script, because of his pride over having bested the ‘Great Old Man’ last year, he’d had no real plan and been forced to improvise. And he’d be the first to admit he wasn’t the best improviser. Hence this mess. So his sovereign had every right and reason to throw the book at him.

Except then it would be the curs of Constantinople, those…newspapermen. And he’d be defamed not for what he’d done wrong, but for whatever they could think of to boost their sales. Probably somehow sleeping with Elizabeth. He had been damned by them for all sorts of things last year, and he had not forgotten, or forgiven. He still smiled at the thought of those who’d gotten a forum breakfast. He’d been damned for being cautious; well, he’d own up to that. If he’d followed their advice, there’d be another ten thousand dead Romans, at minimum. And his soldiers knew that too, and resented it. And so, no matter how the Emperor acted, he would go out like Gabras, and Michael Laskaris, descendant of Theodoros Laskaris Megas, had far too much pride to leave like that, and be seen as a whipped dog by those curs.

I will not go out like Gabras. Mocked and humiliated and scorned by men who’d foul themselves if a gun went off next door to them. By worms who would slander a man for no reason if that would put a few folloi in their pockets. He’d been at Astara, at Mohacs, at Buda, at Nineveh, and all the western battles of this war. He’d seen death and carnage and slaughter and pain, and he would not be judged by those who’d not been in the dragon’s mouth either. He would not go out like Gabras.

As the Spartans said, with this shield, or on it. There were no other choices. With this shield was not an option, not for him anyway. So it’d be on it. Rather than Gabras, he would go like Theodoros Sideros instead, the father of Demetrios III who was slain on the field of Dojama, rather than return in shame and disgrace. For as he said, better a noble death than an ignominious life.

And yet he would not, if God be kind, go out like Theodoros. For the Domestikos had just been slain on the battlefield. Perhaps he had killed a few of the Persian rankers, but that was all.

He was quite grateful for his injury now; it’d given him the exit he wanted. Being captured in good health like this would look far too suspicious. But in his half-dead look, it seemed much more reasonable that he couldn’t keep up. And so he could serve his Emperor one more time, perhaps making up for his mistakes this season, and simultaneously pour full scorn on those vermin.

Some riders were approaching, one of them attired in the uniform of a general in the service of the House of Wittelsbach. It seemed like his conditions for his surrender, which he’d communicated via the patrol that had found him, had gone through. God, please give me strength.

The riders arrived, the general dismounting and approaching. Michael struggled to his feet, finishing off the kaffos, adjusting his dress sword strapped to his side. He was in the full parade uniform of a Roman Domestikos, outshining the mud-splattered and somewhat shorter German in front of him.

“I am General von Mackensen, in service to the Emperor Theodor I,” the German said in his own tongue. “Here to accept your surrender.”

“I said I would only surrender to Emperor Theodor or, failing that, Marshal Blucher,” Michael replied in his heavily-accented German.

“I’m afraid that both his Imperial Majesty and the Marshal are busy at the moment.” There was cannon and musket fire to the southeast. “You may surrender to me.”

“Those are not my terms.”

“My good sir, you are not in a position to bargain. You may meet with the Emperor after you surrender, but only after you surrender.”

Michael worked to keep his despair off his face. If I could get within arm’s reach of either one of them for two seconds; that’s all I need. And this is over. But it was most doubtful he could get to Theodor after captivity without being searched, and then this would all be for nothing. And that he would not allow. His shame, isn’t of being erased, would be amplified. But…while this wouldn’t be a death blow to the Allies, it would still hurt, a lot.

“Very well,” Michael replied. “You are a man of rank and honor. It is a privilege to surrender to you, good sir.” God, please give me strength. It all came down to seconds. He unbuckled his sword and held it out in his right hand.

Mackensen stepped forward. “It is an honor to accept your surrender, good sir.” Mackensen gripped the sword, Michael letting go.

Michael’s left hand grabbed Mackensen’s collar, yanking the German forward. The guards started forwarded as the general started to jerk backward. Michael’s right hand came swinging, hitting the inside of the Domestikos’ left elbow, striking the flintlock mechanism there under the baggy coat sleeve. A German soldier started to grab Michael’s shoulder.

The two grenades, to which the flintlock mechanism had been connected by a nimble-fingered and explosively-inclined dekarchos, exploded in Michael’s and Mackensen’s faces.

1634 continued: Likardites can’t move quickly with all the refugees in tow. A few are useful from his perspective, quick-moving, armed, and able to be pressed into service as camp guards or escorting their fellow refugees. But there are large numbers of children and old ones. If Likardites abandons them, the Allied troops nipping at his heels from south Skoupoi probably will massacre them. And there’s the matter of what that will do to the morale of much of the Roman rank and file.

To buy himself time, he has the Macedonian tagma force-march ahead of the main body. Under the command of Andronikos Koumpariotes, it fords the river in front of the downstream-marching Allied army, setting up a stout defensive position. Taking advantage of the narrow mountainous terrain, the aim is to hold up the Allies long enough for the slow-moving main body to reinforce the Macedonians.

Blucher though expected something like this to happen, and during the winter he’d spent a lot of effort recruiting good mountain troops from the Tyrolese and Swiss. While almost two hundred cannons pound the Macedonians in the front, the Tyrolese and Swiss work through the crags to turn the Roman position. Meanwhile the best Roman mountain troops are with the Army of Georgia or currently storming the Brenner Pass.

Hit from both front and flank, the Macedonians are hammered brutally, although they smash at their assailants, but steadily they are ground down and back. They retire onto the main body, now across the river with the refugees still dragging, holding together but very badly damaged.

That engagement sets the template for what follows. Roman positions are pounded by the Allied artillery train, which outnumbers the Roman at this point close to five to one (and in terms of weight of shell the odds are even longer), as Allied mountain troops turn their lines and come piling down their flanks. And yet Roman guns hurl double Vlach-shot in the teeth of Allied infantry and Roman muskets flay the head of Allied assault columns even as they break through the Roman lines, only to find the Romans, fewer in number perhaps, but still fighting, reforming a new line that must be stormed in front of them.

It is 180 kilometers as the road goes from Skoupoi to where the mountains fade away to open up to the Macedonian plain. One hundred and eighty kilometers and twelve days of agony. Twelve days of terror and blood and death.

Agony for the Romans. The agony of retreating, forced to abandon their wounded. The agony of huddling under the pounding of the never-ending guns, of the whistle of iron clipping off rocks in their courses, to add another tide of death.

Agony for the Allies. The agony of advancing, of treading over their fallen. The agony of leaning forward as the never-ending Roman muskets roar down on them, of the whistle of iron clipping off rocks in their courses, to add another tide of death.

Agony and heroes.

On the Roman side, there is Tourmarch Alexios Maniakes, who once fought alongside Kaisar Andreas at Volos. Leading his tourma in a daring night raid, he wreaks six hundred Bohemian casualties before he retires with the dawn. There is the ‘Mad Lyrist’, the Strategos of the Opsikians, Iason Tornikes, who to bolster the morale of his men under another of those bombardments, stands and plays a tune on his politiki lira. Most can’t hear him, but they can see him, and that is enough. While sounding decidedly crazy to modern ears, such deeds earn great admiration and respect from the men, on both sides, who expect, and require, their officers to show utter contempt for death.

And then there is Odysseus. Always where the fighting is thickest, encouraging and succoring, covering retreats and leading attacks to relieve pressure. During the twelve days, four horses are killed under him and nine bullets or shell fragments pass through his clothing; he suffers not a scratch. By the end his mere presence is enough to cheer the men around him, and more than a few are starting to call the short dark-skinned Kaisar “their Little Megas”.

On the Allied side, there is Archbishop ‘Bone-Breaker’, leading his men forward into a hail of bullets, totally indifferent to danger. On May 23 he is nearly captured or killed, but is rescued by his ‘nephews’ Karl and Paul, who are actually his illegitimate sons. There is King Casimir. His cavalry are near useless in this fighting, but still he presents himself in blinding pageantry under the muzzle of Roman guns, deliberately drawing their fire down on him to lure it away from those making the actual attacks.

And then there is Blucher. Always where the fighting is thickest, encouraging and succoring, urging his men forward. Theodor was disturbed by the manner of Mackensen’s death, but it is the Marshal who takes it hardest. To compensate, he throws himself into the fight. Undoubtedly it galvanizes his men, inspiring them to even greater deeds, for no young man will let it be said that he couldn’t do what a man four times his age could. And yet there are some who feel that this is not bravery, but suicide. On May 27 he is gently but firmly told by his men that they will go and take that hill, but first “Marshal Blucher to the rear”. He goes to the rear and his men take that hill.

While this is happening, the northern flying column mauls one small Allied wagon train but then after a delay gets a rider bearing news of the debacle at Skoupoi. Realizing his original orders are pointless, the commander Konstantinos Sanianos breaks camp and starts racing south himself. A native of Lower Macedonia, albeit not this particular area, his goal is to find a more knowledgeable local (those soldiers with local knowledge had been detailed to the original, now ‘southern’, flying column and thus not available for this expedition; Sanianos himself was the next best choice) and use his familiarity to infiltrate through the mountains and come piling onto Blucher’s rear while he’s still clawing south against the main body.

A day’s march on, Sanianos is met by an old hunter and trapper, a veritable mountain man that Sanianos knows from his childhood, a man with a reputation of knowing every goat track from the Danube to the Adriatic. The hunter gladly agrees to help in exchange for a token fee. The column sets off in high hopes of salvaging the situation. Except then the hunter leads them nowhere and into a dead end, demanding an exorbitant sum in exchange for actually leading them out of here. Absolutely beside himself with rage that this old hunter has been leading them on a literal rabbit’s trail while his friends are fighting and dying, Sanianos kills him on the spot. The column works its way back out of the mountains, but the ‘detour’ means it is too late for them to help their comrades.

On June 1, the long-running battle finally exits the mountains, both armies tumbling half-dead onto the plains. A month ago they were both over 80,000 strong. Now the Allies have a fighting strength little more than 55,000 strong and the Romans are down to 50,000 (although 10000 Romans are up at Vidin and the northern flying column once it arrives boosts the Romans up to parity with the Allies). Many of those losses are wounded who eventually return to the ranks (although here the advantage goes to the Allies since they didn’t have to abandon their wounded at points), but the slaughter is horrific even to veterans of the battles along the Danube.

Now there is room for maneuvering, although neither side is capable of much at this point. Likardites stumbles backward, still shepherding 40000 refugees, organizing the stripping of the Macedonian countryside to deny resources for the invaders. Somehow Blucher, who is losing weight at an alarming rate, manages to keep the army together rather than the men scattering for food. There are still some running battles between the two sides, but after the Twelve Days both are keen to have a breather, and a gap soon opens up as the Allies pick clean the area for food. The Romans, in their haste, have gotten the most obvious but not had time to be particularly thorough.

In Lower Macedonia they start getting news of the response of the capital to the events in Macedonia. It is a torrent of abuse.

Newspapermen in the capital had learned to steer clear of the Imperial family, but now with Michael Laskaris dead they feel free to let loose. There is a new crop this year, and since they don’t have earlier access to the news like those on Demetrios III’s shortening list-of-people-he-likes, they make up in ‘commentary and analysis’.

Michael Laskaris’ name is damned and dragged through the mud, everything thrown at him, the lurid prose a way to draw readers and sales. Except the problem is the Roman soldiers of the Army of the Danube liked Michael. Unlike these newspapermen, he didn’t seem to want to get them all killed, which is why when some fell at Skoupoi they ‘asked’ Constantinople if they were finally satisfied.

And it seems the answer is no. For the soldiers and officers of the Army of the Danube are dragged through the mud also, condemned as cowards, idiots, perhaps even traitors. The Twelve Days didn’t break the army of the Danube, but this, coming afterwards onto the traumatized souls of the survivors, shepherding even more traumatized refugees, is one more straw. And something snaps.

Desertions, which weren’t a problem before despite the terrors of the Twelve Days, suddenly are, several hundred Roman soldiers dropping their muskets and disappearing into the countryside. Dying for a reason can be borne, but dying for nothing, or for such ingrates, that cannot be borne. A plea from a delegation of refugees, including the Maid of Skoupoi, begs the soldiers not to abandon them. It stops the bleeding, but cannot heal the existing wound.

This is where the literate ‘modern’ culture of Rhomania turns out to be a problem. For all these soldiers are used to newspapers. Even isolated villages will eventually get them, albeit delayed a month or two, where it is a big event for a literate villager to read them out loud for those who cannot. So not only are they getting slandered, frustrating enough, but they know the slander will reach the ears of their family and friends back home.

On June 4 the Army of the Danube arrives at Thessaloniki, a sullen, demoralized, bitter, resentful force. It’s been speculated by some historians that if Odysseus Sideros had asked, the Army of the Danube would’ve marched on Constantinople. Thankfully for everyone whose name isn’t Theodor, the thought never seems to cross his mind.

Gladly getting rid of the Skoupoi refugees, Likardites reinforces the garrison, and then in the evening has a nervous breakdown, collapsing on the floor of his tent. (While records are patchy, particularly for the Germans, and while keeping in mind the limited medical knowledge of the period, veterans of Skoupoi and the Twelve Days on both sides seem to have been substantially more prone to nervous breakdowns and madness in later life.)

He is put in a hospital in Thessaloniki. He’s suffered a torrent of abuse in the papers personally, both from Constantinople (which come on a daily packet, although the issues themselves are a few days old by the time they arrive) and a couple in Thessaloniki. One in Thessaloniki sends him some women’s clothing and a spindle to mock him for his weakness. Ashamed of his weakness and his failure, not in the best of mental health already, Hektor Likardites blows his brain out with a kyzikos. The next day several soldiers from the Army smash in the door of the editor responsible and beat him to death with the butts of their muskets.

Taking his place as commander is the ‘Mad Lyrist’ Iason Tornikes, who, along with the rest of the army, is now in an even worse mood. Hektor Likardites was a good and close friend of his, going back to their School of War days where Likardites was one year ahead. Many of his other friends’ bones are being picked clean in the north, and he is hearing their names mocked and honor slandered. One of his first tasks after the suicide of his friend is to write a very blunt letter to his sovereign, which is rushed to the capital via monore.

In it he states plainly that the Army of the Danube in its present condition is a frail reed that should not be leaned upon, and for that Tornikes blames Constantinople, not Blucher. The army and officers need to be treated better; they need to be treated as if their sacrifices are appreciated. They destroyed half of the Allied army last year, and were damned for not destroying all of it. They destroyed a third of the Allied army so far this year, and are damned as cowards. Their first commander, who they liked and respected for safeguarding their lives whilst others wished apparently to throw them away, killed Blucher’s right-hand man and is slandered before his corpse is even cold. Their second commander, who they admire for holding the army together during a horrific retreat, and whom none of them blame for cracking when the burdens of command are added to their shared nightmare, was humiliated into suicide when his mind was weak. This cannot be borne.

Tornikes’s letter is accompanied by one from Odysseus, who confirms the Mad Lyrist’s analysis. He also adds that the officers, including himself, feel that they are expected to be like Andreas Niketas and utterly annihilate the Latin army whilst being outnumbered 2-to-1. If they can’t do that, then apparently they are all idiots and cowards. And they don’t appreciate it.

Demetrios III understands. First the carrot. The Patriarch of Constantinople issues a statement that declares that Hektor Likardites’ death was not a suicide, which is a sin, but by ‘Axios Fever’. To this day, that is what Romans call PTSD.

Demetrios III meanwhile issues orders for planned expansion of pensions for widows and orphans of soldiers killed in service, as well as soldiers’ homes for those whose injuries make it difficult or impossible to earn a living afterwards. He also posthumously awards Michael Laskaris and Hektor Likardites with Order of the Dragon with Sword medals, the highest honor that can be bestowed on a Roman soldier to this day. The former is for the 1633 campaign and his slaying of Mackensen, and the latter is for his leadership during the Twelve Days. Tornikes is granted the Order of the Dragon with Mace medal, the next tier down, as is Odysseus Sideros. More medals of the lower grades (Order of the Dragon with Spear, and the three grades of the Order of the Iron Gates) are made available to Tornikes to distribute as he sees fit. Simultaneously a handwritten note of thanks and appreciation of their sacrifice from Emperor Demetrios III is read out to the troops.

Meanwhile, Lady Athena Siderina left Constantinople for Thessaloniki before Likardites’ suicide, but after a quick reunion with her big brother she quickly gauges the lay of the land, and starts to tour the army still encamped near Thessaloniki, as well as the hospitals inside the city. The combination of that, alongside her father’s efforts, are most uplifting for the soldiers. The capital may not care about them or their sacrifices, but the Imperial family does.

Feeling better, the bulk of the army moves east to cover the Via Egnatia to the capital. Tornikes’ plan is to reinforce his army with some of the new tourmai recruiting in Thrace, plus the 14000 Pronsky soldiers moving down from Russia. While Blucher is stuck besieging Thessaloniki, pounding at its formidable and fully modern ramparts, he can give those new tourmai some much needed drill. He has no desire to fight a Second Ruse size battle with First Ruse troops. At the same time, he starts raiding Latin foragers and outposts, but he also tells Demetrios III that the aggressive spirit of the army is still quite weak. The Emperor’s and his daughter’s actions have helped a lot, but the scars remain. The news of the stick Demetrios is using in Constantinople, this time being more thorough than last year to ensure this doesn’t happen again, is most welcome though.

Even with the partial stripping of Macedonia, the Allies have found enough to not be starving, for now. But they are going to need to forage widely, which presents opportunities to the Romans. Hellas proper needs to be defended as well. The Paramonai, which by now are down to nine thousand, are reinforced by five Roman tourmai (which combined are only 3100 strong) and sent westward as the Allied army finally staggers up to the walls of Thessaloniki.

The ramparts of Thessaloniki, June 5, 1634:

Demetrios looked down the barrel of the cannon. It was mounted on one of the many bastions, looking out to the fields outside of the city. They’d been mostly cleared, although there still was frantic work going on westward. There was a large column of people scurrying toward the city gates, carrying their possessions and children on their backs and on their animals’ backs and in their carts. Behind him the bells of the city’s churches tolled and a battle-line ship and a transport worked their way into the harbor.

He squinted again, adjusting his glasses on his nose. He strongly believed in pre-sighting his guns before a siege, if he had time of course. There was always a bit of ‘wobble’ with the precise ranging of each gun. Every cannon was different; they had different characteristics, quirks of their own, dependent on the manufacture and quality of the metal, the precise boring of the tube. Cannonballs always fit a little bit differently; they had quirks of their own. Quality of powder could affect the shot, the humidity of the air, the temperature of the day. There were lots of little factors that could adjust how a gun performed. A lot of them were unknown until the day of battle themselves, but he believed in getting a feel for each gun when he had time to thoroughly make their acquaintance.

He looked at the marker where he suspected Vauban would emplace one of his batteries. He wanted his cannons pre-sighted on that place. Once they were, he’d remove the marker.

Out of the corner of his eye he saw a party approaching along the walls but he ignored them. “Set it to 500,” he ordered.

“Are you sure?” someone said. “Looks like 520 to me.”

He looked over at the speaker. It was a young woman, dark-hued and a bit shorter than him, dressed in riding pants and a silk shirt. Somewhat unusually, she had two finely-crafted kyzikoi in holsters next to her ribs. There was a gash that Demetrios could tell was from a knife on her left forearm. “Lady Siderina, I didn’t expect to find you here.” He bowed his head slightly.

They’d met before briefly, back when he was in Constantinople getting baptized into the Orthodox faith. Her father, Emperor Demetrios III, had been his godfather, hence his choice of a Christian name. That hadn’t raised many eyebrows. His choice of a surname though had, but the opportunity had amused him too much to pass it up, and given his station he had the clout to make it happen. Sometimes it seemed like a silly thing to insist upon, but it simultaneously rubbed an old man’s ego and entertained him.

“Here for the troops. Young men fight better when a princess is watching them.”

“They’re also more stupid,” Demetrios observed.

She smiled. “It’s hard to notice sometimes.” Demetrios snorted. She looked out at the marker. “Are you sure?”

“We’ll find out, won’t we?” He lit the touch-hole. The cannon roared and the ball flew, plowing into the ground and throwing up a spray of dirt just beyond the marker.

“505,” Athena observed.

“You were close,” Demetrios replied.

“Yeah, but you were closer.”

Demetrios thought for a moment and then gestured at the guns on the other end of the bastion. “Care to pre-sight some of the other pieces, your highness?”

Athena’s face lit up. “Oh yes, I would.” Demetrios Poliorketes, formerly Turgut Reis of the Ottomans, couldn’t help but laugh.

1634 continued: As Thessaloniki prepares, there is more fighting to the west. A large Allied foraging party, about twelve thousand strong, mostly Bohemians and Hungarians, heads west following the shoreline, stripping the countryside bare of what remains. At the village of Methoni they run into Odysseus. The three-hour long battle is a tactical draw, but the Allies retreat during the night, although it is just a rebuff, not a rout.

Instead they swing west, looking for greener pastures. Using the expertise of the locals who are decidedly more loyal this time, moving along hunting and grazing paths, Odysseus swings around in front of them, the Allies colliding with him at the village of Kidonochori, just east of Veria, 73 kilometers west of Thessaloniki.

Making like he has weaker cavalry than the Allies, he prompts the Allied cavalry to attack, forcing the Romans to form square. The plan is that the Allied infantry, still in line formation, can then pound them to pieces with musketry. Neither side has much in the way of artillery.

But as the Allied cavalry swirl around the Roman infantry squares, the Roman cavalry spring from ambush, piling into their flanks, some of the kataphraktoi and Pronsk lancers literally impaling Hungarian mounts with their lances. Caught between the hammer of the Roman cavalry and the anvil of the infantry squares, the Allied horse is shattered.

The Paramonai and Roman infantry rapidly deploy into line, too quickly for the Allied infantry to take advantage, and the two infantry lines blaze away at each, reaping a cruel harvest. But then the Roman cavalry wheel back into the fight, smashing in both flanks of the Allied line nearly simultaneously. They disintegrate.

Methoni is largely irrelevant. Kidonochori is not. For eight hundred casualties, mostly in the infantry firefight, in his second battle as commander Odysseus inflicts twenty seven hundred, with another three or four hundred picked up by the locals shooting down stragglers. Although it doesn’t stop them altogether, it sharply curtails foraging expeditions westward, with all the attendant strain on the Allied commissariat. Although the atmosphere at the Roman camp isn’t particularly joyful. The feeling in officer country is ‘we won, but our prize will be to be condemned for all the ones that got away’. Odysseus, who is feeling it as well, tells his father that ‘the current attitude amongst the Army of the Danube is not conducive for a direct battle with Blucher.’

The ramparts of Thessaloniki, June 8, 1634:

Alexandros Drakos put down his dalnovzor and looked out at the Allied army lumbering up into position just outside of cannon-range. “There’s a lot of them,” he said. Compared to what they’d been a month ago, he intellectually knew that there really weren’t that many of them. But after the Twelve Days, he was surprised that anyone, on either side, had survived that horror, much less so many. He had nightmares of those days, and he knew he was far from the only one. His tourma had taken 30% casualties and so was an easy candidate for garrison duty.

“The thickest grass is easier to cut than the thinnest.”

Alexandros looked over at the speaker, his wife. Daughter of the Emperor, young and beautiful and strange. “I don’t think quoting Alaric, of all people, is appropriate at this time.”

She smiled at him and shrugged her shoulders. “It’s what I do.”

He raised an eyebrow at her. She raised one at him. To the east, the bells of St Demetrios tolled as three warships and four transports worked their way into the harbor.

A cannon roared from a bastion.

The siege of Thessaloniki had begun.

[1] Ancient Greek name for the town. Thanks to @Lascaris for the information.

[2] Napoleon did this at the siege of Toulon IOTL.

[3] The OTL Kale Fortress.

[4] This is the TTL version of the Stone Bridge of Skopje.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

“When players of equal skill are matched,

Then victory hovers between;

Perhaps your opponent's a genius,

So put on your lowliest mien.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL).

“Remember enough is as good as a feast,

Having sketched a good snake don't add legs to the beast;

And in fighting remember that others are bold,

And tigers have claws though their teeth may be old.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL)

“The due time of battle will arrive, call it not forth, when furious Carthage shall one day sunder the Alps to hurl ruin full on the towers of Rome…”-Jupiter, the Aeneid, Book 10.

“Thrice wicked was Cao Cao, but he was bold;

Though all in the capital he controlled,

Yet with this he was not content,

So southward his ravaging army went.

But, the autumn wind aiding, the Spirit of Fire

Wrought to his army destruction dire.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL)

“"Where is the principle for yielding when I have my orders to rescue the city and so far have not succeeded?" Throwing off his helmet, he cried, "The happiest death a man can die is on the battlefield!" Whirling his sword about, Yu Quan dashed among his enemies and fought till he fell under many wounds.

Many were they who yielded at Shouchun,

Bowing their heads in the dust before Sima Zhao.

Wu had produced its heroes,

Yet none were faithful to the death like Yu Quan.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL)

“O comrades, for not ere now are we ignorant of ill. We have been tried by heavier fortunes, and to these also God will put an end.”-Aeneas, the Aeneid, Book 1.

“Though fierce as tigers soldiers be,

Battles are won by strategy.

A hero comes; he gains renown,

Already destined for a crown.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL).

“Individuals matter in history. Great heroes and prophets can inspire mighty causes that shake empires. And a single asshole or idiot can ruin everything for everybody.”-Emperor Demetrios III, Collected Writings.

1634: Michael Laskaris, commander of the Army of Danube, currently 84000 strong, begins to push on Vidin in May. His goal is to retake that and then march on to Belgrade. If he can seize those two fortresses, he’ll effectively sever the Allied supply lines and force them to withdraw from Upper Macedonia and Serbia or face starvation and destruction. He expects the fighting to be hard; Vauban knows how to defend as well as defeat fortresses and both Vidin and Belgrade are some of the most formidable in Europe.“When players of equal skill are matched,

Then victory hovers between;

Perhaps your opponent's a genius,

So put on your lowliest mien.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL).

“Remember enough is as good as a feast,

Having sketched a good snake don't add legs to the beast;

And in fighting remember that others are bold,

And tigers have claws though their teeth may be old.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL)

“The due time of battle will arrive, call it not forth, when furious Carthage shall one day sunder the Alps to hurl ruin full on the towers of Rome…”-Jupiter, the Aeneid, Book 10.

“Thrice wicked was Cao Cao, but he was bold;

Though all in the capital he controlled,

Yet with this he was not content,

So southward his ravaging army went.

But, the autumn wind aiding, the Spirit of Fire

Wrought to his army destruction dire.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL)

“"Where is the principle for yielding when I have my orders to rescue the city and so far have not succeeded?" Throwing off his helmet, he cried, "The happiest death a man can die is on the battlefield!" Whirling his sword about, Yu Quan dashed among his enemies and fought till he fell under many wounds.

Many were they who yielded at Shouchun,

Bowing their heads in the dust before Sima Zhao.

Wu had produced its heroes,

Yet none were faithful to the death like Yu Quan.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL)

“O comrades, for not ere now are we ignorant of ill. We have been tried by heavier fortunes, and to these also God will put an end.”-Aeneas, the Aeneid, Book 1.

“Though fierce as tigers soldiers be,

Battles are won by strategy.

A hero comes; he gains renown,

Already destined for a crown.”

-Romance of the Three Kingdoms (OTL).

“Individuals matter in history. Great heroes and prophets can inspire mighty causes that shake empires. And a single asshole or idiot can ruin everything for everybody.”-Emperor Demetrios III, Collected Writings.

To help counter that, and to combat the reported new and improved Triune artillery train, he has pulled together cannons from gun parks throughout Europe to reinforce his own. His gun line is twice as big as it was a year ago. Blucher’s grand batteries won’t have much luck with that. The downside of that is the slower pace of the army.

He probes toward Vidin, moving cautiously so as to avoid any ambushes. In the smaller skirmishing around Vidin at the end of last year, both sides showed an ability to play that game. And considering his large and necessary artillery train, he wants to avoid the fate of Stefanos Monomakos, who during the Great Uprising saw most of his artillery train destroyed by an Idwait ambush, ruining the Roman offensive for the year.

And so he is caught completely off-guard and well out of position when Blucher’s army of slightly over 80,000 storms across the border and assaults Skopje, in the upper Axios River valley.

Demetrios III had expected something like this to happen. He’d argued during the winter that something like this would be entirely in keeping with Theodor’s nature. However he left the decision in the hands of his Domestikoi, and they’d disagreed, expecting Blucher to play a hard defensive campaign around Vidin/Belgrade. Demetrios had not ordered them to guard against this, but his attempts at convincing them had mainly served to make the Megas Domestikos and the Domestikos of the West more convinced in their own opinion. Demetrios III is their Emperor and a good administrator, but they know as well as he that he is no soldier.

There had been some reports in Serbia (the information is sparser now that Blucher is mainly operating in non-Roman territories) that suggested a southward movement but Michael had dismissed them as misinformation to distract him. Helping to push that narrative is Despot Lazar, who is rather put out by Demetrios’ recognition of his younger brother as King of Serbia. Now his wagon is truly hitched to Theodor’s train. With experience of how Romans operate, he captured a couple of Roman spies during the winter and turned them, whether by threats or bribes is unknown, using them to feed false information to Michael that ‘confirm’ that the real preparations for a southward advance are truly a feint.

By this point Michael is starting to set up his first parallels around Vidin, entrenching his artillery and growing concerned about Blucher’s absence. The news is delayed in reaching him as due to bad weather the semaphore line from Thessaloniki to Constantinople wasn’t able to operate but he immediately breaks camp with the bulk of his army to march to Skopje’s relief. He leaves behind a portion though to siege Vidin, including the bulk of his amassed artillery and all of the heavy pieces.

The leaving of the artillery is a gamble, substantially weakening his army, but he has to do so if he wishes to move fast. He’s still marching with an array of field pieces which can keep up, but not in the numbers he’d gathered over the winter. To move his guns and supply wagons more quickly he needs more teams of horses, and he only has so many of those to go around. Therefore many cannons have to be left at Vidin in the name of speed. Some of the losses though can be made good by pulling from the reserve guns and mounts stabled at the Serdica Kastron. That all said, the batteries he still commands would be impressive…until compared to that of the Triune train, twice the size of last year’s. Henri II, for his part, also wants to send a reminder to Rhomania of the Triple Monarchy’s power.

But leaving Vauban unmolested at Skopje is not, in Michael’s view, an option, after seeing the devastation wrought along the south bank of the Danube in Bulgaria and hearing reports about Upper Macedonia. Skopje, along with Ohrid, were the two key citadels that kept the Allies locked into Upper Macedonia (except from some raids). If Skopje falls, Blucher has a clear shot straight down the Axios River valley which leads into Lower Macedonia.

The region has a well-developed and maintained road network and Lower Macedonia, once one gets into the coastal plains, is per-capita possibly the richest region in the entire Roman Empire. The Macedonian theme has 2.4 million inhabitants, second only to Thrakesia, and includes Thessaloniki, the second city of the Empire. It is more than capable of sustaining even the Allied host for a campaign season, and there’s no telling the moment of damage they could cause in the meantime. But if Michael can halt the Allies while they’re still in the mountainous uplands and hold them up, they’ll either starve or be forced to retreat. However for that to happen, Michael absolutely has to move fast.

Skopje is the third largest city in the Macedonian theme after Thessaloniki (170,000) and Dyrrachion (60,000) with a pre-war population of 35,000, although refugees from parts of Upper Macedonia doubled it at one point. Some have moved on to Lower Macedonia or further afield, but many remained in the city. There was war work available, the garrison here provided good protection against Allied raiders, and many could also be supported by family relations in the hopes of returning soon to their lost lands. Before the Allied onslaught, some of the inhabitants of the outlying villages manage to flee to the city, boosting its population back up to 60000.

The city is known as Skoupoi [1] to its Greek-speaking inhabitants. It has modern defenses, but their size and sophistication are not that impressive. It was taken by the Hungarians and then recaptured by the Romans during the Mohacs Wars, neither side having any serious difficulty. Given the expense of building top-notch modern fortifications, the money was never available to do more. The Danube and eastern citadels were what sucked up the budget for kastron-building.

Where money was spent was on the transportation infrastructure of the region. The old Via Militaris runs through Skoupoi southward to intersect with the Via Egnatia near Thessaloniki. It’s been refurbished and expanded, paralleled by the ‘Ore Road’, a new construction from the Flowering, built to ease the transportation of produce and livestock (despite the unofficial name) to Thessaloniki’s demanding markets.

There’s much work on the Axios itself from the Flowering as well. Much is for flood control, but also to make the river useful for flat-bottom barges to carry loads of timber and ores from the mountains to the foundries and workshops of Thessaloniki. This parallels other riverine works in the Empire both for flood control and to improve navigation, primarily on the Meander and Halys Rivers in Anatolia. Other works are to facilitate the use of water power for various tasks; the mill that gave the battle of Miller’s Ford in the War of the Rivers its name was one of these.

Blucher hits Skoupoi fast and hard, knowing that he cannot afford to be stuck in the mountains for long. Wagon trains are coming down the Via Militaris from Belgrade, but that’s a far cry from the Danube. They can provide him with the shot and powder he needs; Blucher absolutely wants to avoid the lack-of-powder nightmare from last year. But to feed his army, he needs to get to Lower Macedonia fast.

Vauban is well aware of this. Historians debate how privy Vauban is to his master’s plans regarding Emperor Theodor, but no one can doubt that he did, and does, his utmost throughout his assignment with the Allied army. The simplest explanation for that is a victorious Roman army may end with one Marshal Vauban being made dead in the process.

So he is much more aggressive here. His tactics are normally methodical and inexorable, with minimal risk to the besiegers, but at the cost of being slower. That’s not an option here so he pushes his men, digging their parallels closer and working the guns to smash the Skoupoi defenses flat.

The men know this too so they also work harder. Yet despite their situation there are few desertions. Partly there is the example of last year, where those who deserted ended up being blasted from the mouths of cannons, while those who stayed with the standards had a chance to live. While Lazar is cooperating with Theodor (although Blucher pointedly makes sure to keep the Despot far away from a battlefield command) individual Allied soldiers still stand a good chance of being bushwhacked by Serbian peasants, for their boots if nothing else. The only difference from Rhomania is that their body will be dumped in a hidden hole rather than mutilated and left in public view.

There are also the Roman partisans from Upper Macedonia. To reinforce his lines, Blucher has pulled the bulk of his troops from the occupied regions of Macedonia save those masking the Ohrid garrison. Unfortunately they are followed by the partisans, whose regular source of supplies has been raiding the Allied garrisons and now come in their wake.

The most dangerous are the two bands of ‘commune partisans’. These are from two small districts that were never occupied, or at least never secured, by Allied forces. The locals in those districts set up little Roman enclaves, organizing their defenses and electing leaders and officials, typically through the preexisting village framework. Because of their small and isolated natures and no possibility of trade (although there was some smuggling, sometimes with the connivance of the garrisons) raiding is essential for their survival. And so the fighting men of the communes followed.

There is also a much smaller third band, which extorted some supplies from Allied garrisons by threatening them with cannibalism. Despite its few members, this force has become quite a bogeyman to Allied troops for that reason. Historians of the period mostly think the cannibalism was merely a creative threat to compensate for the force’s weakness, rather than something actually practiced, although a minority think it was at least practiced at a dark moment to give the future threats some teeth. More than a few of those historians have commented that in Demetrios III’s detailed history, which does discuss this band, he is uncharacteristically silent in this matter.

The city’s garrison is commanded by Kastrophylax Andronikos Laurentios but the heart of the resistance to the Allied siege is Konstantinos Mauromanikos, the Bishop of Skoupoi (and first cousin to the commander of the Army of Georgia). During the Council of Constantinople in 1619, he’d argued that suicide was valid, even commendable, if a member of the faithful was faced with Latin rule. This was voted down but he brings a spirit of fanatical resistance to the defense. Yet while fervor is useful, it doesn’t slow cannonballs.

A pair of storm-able breaches are smashed through the walls on the north side, although the gun crews take heavy losses from sniper fire in the process. To boost morale and encourage volunteers, von Mackensen christens those batteries as ‘men without fear’. [2] The guns are never short of volunteers. A demand for surrender is denied and Blucher orders his men to storm the city on May 14. It will be bloody but he can’t afford to wait.

At that time, 80% of the city is north of the Axios, dominated by the Fort of Justinian [3], built by Justinian well over a thousand years ago. It has been repaired and expanded some since then, but it is still a pre-gunpowder fortification. The city south of the Axios is connected to the north city by a great stone bridge constructed near the end of Andreas I’s reign, which is overlooked and dominated by said Fort. [4]

Fighting is utterly savage in the way only house-by-house urban fighting can be. Battle is waged with every weapon and resource and person who can be brought to bear. It takes two hours for the Allies just to clear the Church of the Ascension of Jesus Christ, with soldiers from both sides firing on each other along the nave.

Spanish painting-The Last Defenders of the Church of the Ascension

[By Joaquín Sorolla - Museo del Prado, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=76135129]

One of the many heroes on the Roman side in the defense is a young woman named Anastasia, the Maid of Skoupoi. While bringing up supplies to one of the barricades, she saw the last of the defenders killed. With the one cannon there already loaded, she fired it into the ranks of oncoming Bavarian troops, so close that one was able to touch the barrel as she fired the double-Vlach shot into their ranks. The carnage drove them back long enough for reinforcements to arrive and secure the barricade.

A Spanish painting of Anastasia of Skoupoi.

[By David Wilkie - Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5763200]

It is an absolute nightmare, of steel and blood and screams, of young boys pleading for their mothers, screaming that they don’t want to die. Of piles of shattered limbs, of gorging ravens too fat to fly waddling through the abattoir, tatters of bowels hanging from their beaks. This isn’t Skoupoi. This isn’t Earth.

This is Hell.