Chapter V, Conventions

“To say that I was pessimistic during the 1900 Presidential campaign would be an understatement. I wasn’t even sure that I would still be the Party’s nominee, let alone win the election. I was determined to campaign as hard as I could, and hope for the best.” This is what Bryan recounted two decades later. Two major challengers emerged against William Jennings Bryan for the Democratic Nomination. The first was Thomas Catchings, a Representative from Mississippi and a supporter of the Gold Standard. The other was Wisconsin Senator William Villas, a fellow Bourbon Democrat. The goal was for Villas to take away Northern delegates from Bryan while Catchings took away Southern delegates. Conservatives hoped that between these two, and a number of favorite sons, Bryan would be denied a majority of delegates.

-Excerpt from The Guide to the Executive Mansion, an in Depth Look at America's Presidents by Benjamin Buckley, Harvard Press, 1999.

In order to defeat the conservative insurgency, Bryan enlisted the aid of his supporters. South Carolina Senator Ben Tillman persuaded many Southern delegates to stick with Bryan. Well before the convention, Milford Howard had distributed films of William Jennings Bryan along with campaign literature throughout the Deep South, hoping that the people would pressure their political leaders to support Bryan’s reelection. Vice President Arthur Sewall tried to ensure the loyalty of the delegates from New England. On July 4 the 1900 Democratic National Convention began in Kansas City, Missouri. Bryan could count on the loyalty of the West, that was certain, but the rest of the state delegations seemed up for grabs. The attempted revolt of the Southern delegates went poorly; Catchings had the support of his home state of Mississippi, along with a sizable minority of the Louisiana, Texas, and Virginia delegations. Many of the West Virginia delegates opposed Bryan, but they were split between Catchings and Villas. The rest of the South stood with the President. Meanwhile, in the Midwest, only Wisconsin supported Villas.

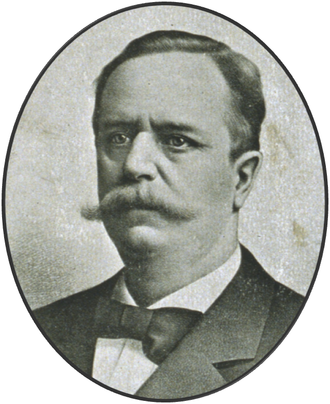

(Left: Thomas C. Catchings, Right: William Freeman Villas)

While the Southern and Midwestern delegations disappointed Bourbon Democrats, the real battle would be in the Northeast. Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts sided with various opponents of Bryan. Maine, the home of Arthur Sewall, was the only New England delegation to support Bryan. Pennsylvania and New Jersey surprised everyone by rejecting the Bourbon candidates. And New York delegates narrowly chose Bryan over former mayor of New York City and favorite son Abram Hewitt. This was because of support from two New York politicians, former Vice President Adlai Stevenson, and former Bryan opponent David B. Hill. Bryan had won his party’s nomination once again. In his victory speech he called on Democrats to unite and continue the work he had begun for farmers, miners, and urban laborers.

The first Republican to announce his intention to run was Thomas Brackett Reed, former House Speaker from Maine. While most Republicans criticized Bryan for not doing enough during the Cuban War, Reed opposed the war entirely. Another contender was Pennsylvania’s Matthew Quay. Robert Todd Lincoln and Frederick Dent Grant hoped to take advantage of their last names. Attorney Chauncey Depew of New York, Michigan governor John T. Rich, Rhode Island governor Charles W. Lippitt, Tennessee Representative Henry Clay Adams, and former ambassador Whitelaw Reid were among the other contenders for the nomination. And then there was William McKinley, eager to have a rematch with William Jennings Bryan. McKinley quickly became the frontrunner. Some delegates were concerned about his electability, as he had previously lost an election in what should have been a Republican year. They rallied around Thomas Reed, the only other candidate that stood a chance at winning the nomination. However, in the end, McKinley was nominated once more. Robert Todd Lincoln was chosen as his running mate as part of a Midwestern strategy. McKinley’s nomination speech at the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia emphasized protectionism, support for the Gold Standard, and a more active foreign policy.

-Excerpt from McKinley, by Raymond Garrett, Charleston Publishing House, 1999.

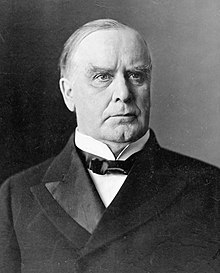

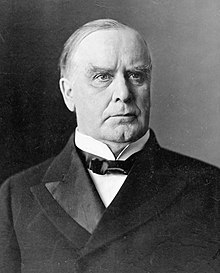

(Left: William McKinley, Right: Robert Todd Lincoln)

There were other party conventions as well. The National Democratic Party nominated Thomas Catchings of Mississippi. This meant that their strategy would focus on the Southern States, as Catchings failed to generate much enthusiasm in the North. The Vice Presidential nominee would be former US Postmaster General William Wilson of West Virginia. The Socialist Labor Party nominated Eugene V. Debs of Indiana for President and Job Harriman of California for Vice President. Their strategy was to specifically target urban workers who were not doing well under Bryan’s Presidency. They portrayed Bryan as a puppet of the silver mine owners and not a friend of the common man. Debs, imitating Bryan, proclaimed “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of silver.”

-Excerpt from The Guide to the Executive Mansion, an in Depth Look at America's Presidents by Benjamin Buckley, Harvard Press, 1999.

In order to defeat the conservative insurgency, Bryan enlisted the aid of his supporters. South Carolina Senator Ben Tillman persuaded many Southern delegates to stick with Bryan. Well before the convention, Milford Howard had distributed films of William Jennings Bryan along with campaign literature throughout the Deep South, hoping that the people would pressure their political leaders to support Bryan’s reelection. Vice President Arthur Sewall tried to ensure the loyalty of the delegates from New England. On July 4 the 1900 Democratic National Convention began in Kansas City, Missouri. Bryan could count on the loyalty of the West, that was certain, but the rest of the state delegations seemed up for grabs. The attempted revolt of the Southern delegates went poorly; Catchings had the support of his home state of Mississippi, along with a sizable minority of the Louisiana, Texas, and Virginia delegations. Many of the West Virginia delegates opposed Bryan, but they were split between Catchings and Villas. The rest of the South stood with the President. Meanwhile, in the Midwest, only Wisconsin supported Villas.

(Left: Thomas C. Catchings, Right: William Freeman Villas)

While the Southern and Midwestern delegations disappointed Bourbon Democrats, the real battle would be in the Northeast. Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts sided with various opponents of Bryan. Maine, the home of Arthur Sewall, was the only New England delegation to support Bryan. Pennsylvania and New Jersey surprised everyone by rejecting the Bourbon candidates. And New York delegates narrowly chose Bryan over former mayor of New York City and favorite son Abram Hewitt. This was because of support from two New York politicians, former Vice President Adlai Stevenson, and former Bryan opponent David B. Hill. Bryan had won his party’s nomination once again. In his victory speech he called on Democrats to unite and continue the work he had begun for farmers, miners, and urban laborers.

The first Republican to announce his intention to run was Thomas Brackett Reed, former House Speaker from Maine. While most Republicans criticized Bryan for not doing enough during the Cuban War, Reed opposed the war entirely. Another contender was Pennsylvania’s Matthew Quay. Robert Todd Lincoln and Frederick Dent Grant hoped to take advantage of their last names. Attorney Chauncey Depew of New York, Michigan governor John T. Rich, Rhode Island governor Charles W. Lippitt, Tennessee Representative Henry Clay Adams, and former ambassador Whitelaw Reid were among the other contenders for the nomination. And then there was William McKinley, eager to have a rematch with William Jennings Bryan. McKinley quickly became the frontrunner. Some delegates were concerned about his electability, as he had previously lost an election in what should have been a Republican year. They rallied around Thomas Reed, the only other candidate that stood a chance at winning the nomination. However, in the end, McKinley was nominated once more. Robert Todd Lincoln was chosen as his running mate as part of a Midwestern strategy. McKinley’s nomination speech at the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia emphasized protectionism, support for the Gold Standard, and a more active foreign policy.

-Excerpt from McKinley, by Raymond Garrett, Charleston Publishing House, 1999.

(Left: William McKinley, Right: Robert Todd Lincoln)

There were other party conventions as well. The National Democratic Party nominated Thomas Catchings of Mississippi. This meant that their strategy would focus on the Southern States, as Catchings failed to generate much enthusiasm in the North. The Vice Presidential nominee would be former US Postmaster General William Wilson of West Virginia. The Socialist Labor Party nominated Eugene V. Debs of Indiana for President and Job Harriman of California for Vice President. Their strategy was to specifically target urban workers who were not doing well under Bryan’s Presidency. They portrayed Bryan as a puppet of the silver mine owners and not a friend of the common man. Debs, imitating Bryan, proclaimed “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of silver.”