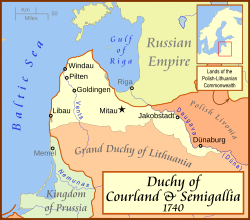

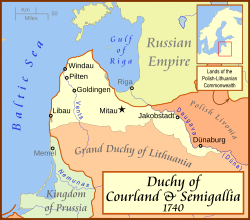

Winter, 1760

Courland, West Prussia

For many years, the Duchy of Courland, a sliver of a nation sandwiched between the giant Russian Empire and Polish Commonwealth, had been dominated by the Czars and Czarinas of Russia. When one line ended, the "suggestion" of the Russian monarch would be responsible for selecting a successor. Decades before, Ernst von Biron had been selected as the Duke only to be removed when he fell from favor under Empress Elizabeth. In recent years, Ernst had been rehabilitated in Russia and, in 1756, his son Peter was installed as the new Duke.

Like many Czars and Czarinas, Elizabeth had long thought about just annexing the territory to her own realms. In 1760, she finally decided to do so. Peter was "advised" to cede his Duchy. In return, he would be shocked to find that the Czarina made him a King.

Since the defeat of Frederick II of Prussia, the Czarina had been given the determination of the fate of the Kingdom of East Prussia. Of similar size, wealth and population to Courland, this seemed an even trade though Biron now carried the title of "King". Thirty-six years old and still unmarried, Biron suddenly realized that he was the last male heir of his line and sought to marry quickly (and to reinforce his claim to Royalty). In 1762, he would select Princess Christianne of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, whom would be twenty-seven at the time.

Though this would not be a happy marriage, Queen Christianne, despite her advanced age, would prove fertile and produce four healthy sons and one daughter before her husband's violence prevented any further relationship between the two.

Duke Peter Von Biron, later King Peter I of East Prussia.

1760

1760

Stockholm

For several years, the Riksdag of Sweden had hemmed and hawed about selecting an appropriate Protestant to take their throne. The House of Holstein-Gottorp was preferred but their former King, Adolf Frederick, would sour them upon that Royal Family. Still, a choice must be made. The youngest brother of the former King, George, would arrive in Sweden to "offer" to take the throne. There was something of a concern that he was part of a plot to put Adolf Frederick back on the throne. The middle brother, Frederick August, had been made Duke of Oldenburg. Neither particularly like their elder brother and soon George Ludwig was deemed an acceptable candidate. Ironically, he was also a former General of Frederick II of Prussia. Still, the man seemed to know his place and would be sworn in at the King of Sweden, Pomerania, Finland, etc even as his eldest brother fumed in Berlin.

1760

The Rhineland

Frederick II had inherited several territories in the northwest German region called the Rhineland. All were relatively small and predominantly Protestant. They included Cleves, Mark, Ravensburg, Linden, Minden and East Frisia. All were stripped by the victors after the war. However, it took several years before the allies came to an agreement as to who would inherit them. France ceded the decision to the Empress of Austria provided that they not be related to the House of Hanover (the British Kings) and "reflected the native religion". In other words, Maria Theresa could not put her Catholic sons on the thrones of the predominantly Protestant nations.

Maria Theresa, being besieged by dozens of requests from assorted Princes to inherit the properties, finally got sick of the matter and just picked who got what.

The younger brothers of Frederick II (uncles to the current Elector of Brandenburg) would eventually be offered the sovereignty of the other possessions of the former King of Prussia in the Rhineland. It turned out most didn't care for Frederick and didn't feel any particular loyalty to his memory (Frederick II huddled in his country estate, ignoring the rest of the world). They also rationalized that keeping the territories "in the Hohenzollern family" justified their actions. Though she despised the House of Hohenzollern, she was monarch enough to know that simply taking away god's rightful Royal Line could be extended to her domains as well and opted to be beneficent in victory. She did, however, break up the assorted little Counties and Duchies and Principalities among several Hohenzollerns to dilute their strength.

The younger brother of Frederick II was Augustus William, whom had died in 1758. His eldest son, Frederick William, now sat on throne of Brandenburg as Elector of the truncated Hohenzollern state. Augustus Williams' second son Prince Henry would become Duke of Cleves.

Frederick II's next younger brother Frederick Henry assumed the Counties of Minden, Lingen and Ravensburg.

Then, Frederick II's youngest brother Augustus Ferdinand was to take the County of Mark.

East Frisia was given to the Dutch Republic.

That left the little Principality of Neuchatel in the Swiss Cantons to be distributed. Having run out of Hohenzollern princes, she cast her gaze about for a Protestant whom had served her well over the years. Given that the Empress loathed Protestants, there weren't man.

Eventually, she just gave Neuchatel to the Swiss-born Financier, Industrialist and former mayor of Zurich Johann von Fries, whom had done well in helping the Austrian Empire regain its finances. The man was reportedly shocked to be informed he was now a Prince. Still, the people of Neuchatel were delighted to find that the Empress wasn't going to hand them over to one of her Catholic sons. Eventually von Fries would return to Neuchatel and take up residence.