It's so close. One blunder and Bartlett will get his ass kicked. The only question is who will get rid of him and take over.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Al Grito de Guerra: the Second Mexican Revolution

- Thread starter Roberto El Rey

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González Part 24: Salamanca disaster Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election Epilogue Acknowledgments Selected World Leaders, 1988—2021 A Very Special AnnouncementAmerica is the surest answer, however, The Mexican people seem just as likely, and I could see a portion of the Mexican Army attempt a Coup if only to stop the decadent and corrupt government if the Battle of San Cristobal is anything to go by.The only question is who will get rid of him and take over.

49ersFootball

Banned

How in the Hell did the Dems choke away 1992 ?

On Clinton: I'm assuming he finishes his 5th term as AR Governor, which was supposed to expire on January 10th, 1995. Interesting to see if he runs in 1996 with the "I Told You So" shtick.

Let's not forget about the Dems will be upping the ante in getting revenge on the GOP in 1993 & 1994 Elections.

On Clinton: I'm assuming he finishes his 5th term as AR Governor, which was supposed to expire on January 10th, 1995. Interesting to see if he runs in 1996 with the "I Told You So" shtick.

Let's not forget about the Dems will be upping the ante in getting revenge on the GOP in 1993 & 1994 Elections.

Last edited:

Bookmark1995

Banned

It's so close. One blunder and Bartlett will get his ass kicked. The only question is who will get rid of him and take over.

America is the surest answer, however, The Mexican people seem just as likely, and I could see a portion of the Mexican Army attempt a Coup if only to stop the decadent and corrupt government if the Battle of San Cristobal is anything to go by.

Again, those are the things dogging Bush Sr.

As much as he hates Bartlett, he hates the idea of Mexico collapsing into chaos even more and having to spend money and resources cleaning the mess up.

Bush is crossing his fingers, hoping for an opposition candidate who can topple Bartlett, bring peace to Mexico, and serve US interests.

Again, those are the things dogging Bush Sr.

As much as he hates Bartlett, he hates the idea of Mexico collapsing into chaos even more and having to spend money and resources cleaning the mess up.

Bush is crossing his fingers, hoping for an opposition candidate who can topple Bartlett, bring peace to Mexico, and serve US interests.

Bush will get the first two st least

Bookmark1995

Banned

Well that's me not going to bed for a while.

EDIT: Oh boy... that was... interesting. Nice to see Zedillo grow a spine and hand in his resignation. I'll admit that I felt quite sorry for Fox, before getting to Caledron's bit... Here's hoping he somehow manages to survive all that. In comparison the EPN bit seems quite light hearted...Great work as always, I really liked this change towards narrative writing for this update!

I know it is a bit late to reply to this, but I consider Nieto's fate to be a lot more... dehumanizing.

While Calderon's situation is horrific, the fact that he is being tortured shows how the corrupt regime considers him to be a serious threat. If he survives his incarceration and joins some social revolt, he can tell the Mexican people "I took the boots of oppression and emerged with my eyes open."

Nieto's fate feels a lot more emasculating: he is a high school nerd having his stuff stolen from him by a gang of thugs. It is better then the police kicking your ass, but there is a certain amount of shame that comes from having your stuff stolen from you.

Bush went into the meeting hoping he could press Bartlett into doubling down on cartels. Bartlett, however, has successively planted into Bush a scenario that is more horrific then a blatantly corrupt Mexico: a Mexico plunged into civil war/military rule. Bush, like any world leader, prefers stability over a costly intervention. So, for now, Bush is stuck dealing with Bartlett as the man who can "keep order."

Make no mistake, though: Bartlett is a fool is he thought he could pull one over the man who RAN the CIA, thinking even the smallest presence of Cuban soldiers can make Bush work with him. He is also a fool if he thinks he can make the cartels into a loyal fighting force.

While Bush will back a man who can keep the peace, he won't back the person who is not only failing to keep the peace, but is actively making the situation worse.

Bartlett, corrupt asshole that he is, will likely make the situation worse as he seeks to maintain his own power and prestige. And his failure isn't something the American public will take kindly, since Mexico and its troubles are quite close to the US.

If he is seen as part of the problem, Bush will be more likely to show him the door.

Precisely. Bartlett walked away from this meeting thinking he'd managed to fool one of the more diplomatically astute chiefs of state in U.S. history. In fact, Bush has begun to grasp what even Bartlett himself isn't seeing: as Bartlett centralizes more and more power within his own hands, he prevents any other figures within the PRI from developing national prominence, which is good for preventing an intra-party coup, but it also means that if something were to happen to Bartlett, the PRI would have a very tough time finding a figure with enough stature to take the reins. The weakness of opposition parties, meanwhile, means that there would be no way of getting a civilian elected President in from outside the PRI umbrella. In effect, under the current situation, if Bartlett were to meet the same fate as Carlos Salinas, it would be very hard to organize a credible successor government. This, of course, is only a recipe for more chaos and confusion, so Bush sees little choice but to support Bartlett for the time being while he searches for a more permanent solution to the issue.

I initially intended to go more into depth about the Zapatistas with this update, but eventually decided it would cloud the focus of the update and make it even longer than it already was. If all goes to plan, I'll include an update on the State of Zapata in either the next update or the one after that!Though I did expect Bush and Bartlett to talk about Cartels and Cubans, I didn't expect them to ignore the Zapatistas, given that Mexico is on the verge of civil war or at the very least societal collapse.

America is the surest answer, however, The Mexican people seem just as likely, and I could see a portion of the Mexican Army attempt a Coup if only to stop the decadent and corrupt government if the Battle of San Cristobal is anything to go by.

The Army's view of President Bartlett has been steadily deteriorating over the past year or so, particularly because Bartlett has been playing a pretty blatant game of favorites with the DFS ever since San Cristobal. They're particularly angry at how since the defeat, Bartlett has ripped most Army battalions away from their beloved wellsprings of patronage and corruption in order to undergo menial "retraining" procedures. That same defeat, however, means that for the moment, the Army doesn't have enough credibility among the Mexican people or in the eyes of the international community to take control of the government without very serious backlash, no matter how bloodlessly the coup goes. If the Army's going to attempt a coup, they can't do it on their own, at least for now.

The Republican Revolution will definitely be forestalled a few years, that's for sure.How in the Hell did the Dems choke away 1992 ?

On Clinton: I'm assuming he finishes his 5th term as AR Governor, which was supposed to expire on January 10th, 1995. Interesting to see if he runs in 1996 with the "I Told You So" shtick.

Let's not forget about the Dems will be upping the ante in getting revenge on the GOP in 1993 & 1994 Elections.

He might do a bit more than cross his fingers—U.S. policy toward Mexico is about to become significantly more interventionist, though perhaps not in the way you'll be expecting!Bush is crossing his fingers, hoping for an opposition candidate who can topple Bartlett, bring peace to Mexico, and serve US interests.

Not just his stuff—his clothes, which gives the added effect of dehumanizing him and humiliating him in one of the most basic ways.I know it is a bit late to reply to this, but I consider Nieto's fate to be a lot more... dehumanizing.

While Calderon's situation is horrific, the fact that he is being tortured shows how the corrupt regime considers him to be a serious threat. If he survives his incarceration and joins some social revolt, he can tell the Mexican people "I took the boots of oppression and emerged with my eyes open."

Nieto's fate feels a lot more emasculating: he is a high school nerd having his stuff stolen from him by a gang of thugs. It is better then the police kicking your ass, but there is a certain amount of shame that comes from having your stuff stolen from you.

In hindsight, I think when I wrote this update, I had in mind that each President's fate would be progressively worse than the last because in my personal opinion, Mexico's Presidents between 1994 and 2018 rank in descending order of greatness. So Zedillo, as a "reward" for his pivotal role in Mexico's democratic transition, gets the catharsis of resigning from a corrupt office, while Peña Nieto, corrupt bastard that he is, is forced to walk home almost naked along busy city streets.

Sorry about the slow pace of updates recently guys! Rest assured that this timeline is very much still going, it's just that I've had precious little free time ever since moving countries earlier this year. My exams are over in a few days, though, so I should have time to finish the next update (which is currently about half-done) over the next week or two!

Bookmark1995

Banned

Precisely. Bartlett walked away from this meeting thinking he'd managed to fool one of the more diplomatically astute chiefs of state in U.S. history. In fact, Bush has begun to grasp what even Bartlett himself isn't seeing: as Bartlett centralizes more and more power within his own hands, he prevents any other figures within the PRI from developing national prominence, which is good for preventing an intra-party coup, but it also means that if something were to happen to Bartlett, the PRI would have a very tough time finding a figure with enough stature to take the reins. The weakness of opposition parties, meanwhile, means that there would be no way of getting a civilian elected President in from outside the PRI umbrella. In effect, under the current situation, if Bartlett were to meet the same fate as Carlos Salinas, it would be very hard to organize a credible successor government. This, of course, is only a recipe for more chaos and confusion, so Bush sees little choice but to support Bartlett for the time being while he searches for a more permanent solution to the issue.

Finding someone in the PRI of stature who also hasn't given in to the corruption? That is going to be one tall order.

I initially intended to go more into depth about the Zapatistas with this update, but eventually decided it would cloud the focus of the update and make it even longer than it already was. If all goes to plan, I'll include an update on the State of Zapata in either the next update or the one after that!

I want to know how Zapata is being run. It is like Rojava, or more like Bolshevik Russia in 1918.

The Army's view of President Bartlett has been steadily deteriorating over the past year or so, particularly because Bartlett has been playing a pretty blatant game of favorites with the DFS ever since San Cristobal. They're particularly angry at how since the defeat, Bartlett has ripped most Army battalions away from their beloved wellsprings of patronage and corruption in order to undergo menial "retraining" procedures. That same defeat, however, means that for the moment, the Army doesn't have enough credibility among the Mexican people or in the eyes of the international community to take control of the government without very serious backlash, no matter how bloodlessly the coup goes. If the Army's going to attempt a coup, they can't do it on their own, at least for now.

You've underscored just how utterly BROKEN the Mexican political system. Not even the military can attempt to resolve the situation, because everybody hates them.

The Republican Revolution will definitely be forestalled a few years, that's for sure.

It really depends on what kind of strategy the Dems pursue. What will they take away from this loss? Are they going "New Democrat"?

Not just his stuff—his clothes, which gives the added effect of dehumanizing him and humiliating him in one of the most basic ways.

In hindsight, I think when I wrote this update, I had in mind that each President's fate would be progressively worse than the last because in my personal opinion, Mexico's Presidents between 1994 and 2018 rank in descending order of greatness. So Zedillo, as a "reward" for his pivotal role in Mexico's democratic transition, gets the catharsis of resigning from a corrupt office, while Peña Nieto, corrupt bastard that he is, is forced to walk home almost naked along busy city streets.

It is still not a fun thing to go through.

I think the Dems will move to the Conservative side even further.

That would just leave to a Progressive backlash faster when things go south for the Republicans. I don't think we'd get athird party of progressives unless the Dems go pretty damn rightwing and the GOP screw up badly to where both parties look like chalices and then the progressives capitalize on it.

I think some people just want to see one wing or the other of the American or any other system get shed on the least shred of an excuse. I of course have not hidden what sort of ATL changes I think would be utopian and which dystopian.

Just looking at it as an objective thing I fail to see how the government of Mexico being even more blatantly corrupt and incompetent than OTL somehow equates to vindicating the right. Certainly if we Mary Sue the hell out of Bush and turn him into Harrison Ford playing a movie President in a situation that is scripted to make him look good--well, sure that has already happened and he got reelected. But fundamentally, I have no grounds to hold that the conservatives and reactionaries suddenly see the light, get religion (of the hippie Jesus kind I seem to recall coming out of the Gospels in weekly Sunday Catholic masses, not "Jesus wants the bums on welfare to get out of bed and get a job!" sort of religion) and then we solve all world problems via cooperation and sharing. And conservatives have none to think we hippy types who were actually around in these days would all just suddenly decide that what is needed is to rally behind our beloved corporate CEOS and work for them 80 hours a week while singing their praises.

Neither George Herbert Walker Bush nor his son are action heroes, the Mexico mess is a mess, and there is no soft landing I see for anyone.

Just looking at it as an objective thing I fail to see how the government of Mexico being even more blatantly corrupt and incompetent than OTL somehow equates to vindicating the right. Certainly if we Mary Sue the hell out of Bush and turn him into Harrison Ford playing a movie President in a situation that is scripted to make him look good--well, sure that has already happened and he got reelected. But fundamentally, I have no grounds to hold that the conservatives and reactionaries suddenly see the light, get religion (of the hippie Jesus kind I seem to recall coming out of the Gospels in weekly Sunday Catholic masses, not "Jesus wants the bums on welfare to get out of bed and get a job!" sort of religion) and then we solve all world problems via cooperation and sharing. And conservatives have none to think we hippy types who were actually around in these days would all just suddenly decide that what is needed is to rally behind our beloved corporate CEOS and work for them 80 hours a week while singing their praises.

Neither George Herbert Walker Bush nor his son are action heroes, the Mexico mess is a mess, and there is no soft landing I see for anyone.

Well, there's no rush. Take your time.I initially intended to go more into depth about the Zapatistas with this update, but eventually decided it would cloud the focus of the update and make it even longer than it already was. If all goes to plan, I'll include an update on the State of Zapata in either the next update or the one after that!

Also, What's Bush's personal opinion on the Zapatistas?

49ersFootball

Banned

That would just leave to a Progressive backlash faster when things go south for the Republicans. I don't think we'd get athird party of progressives unless the Dems go pretty damn rightwing and the GOP screw up badly to where both parties look like chalices and then the progressives capitalize on it.

Still amazed Clinton choked in 1992 SMH. This means he'll finish his 5th term in the AR Governor's Mansion until January 10th, 1995.

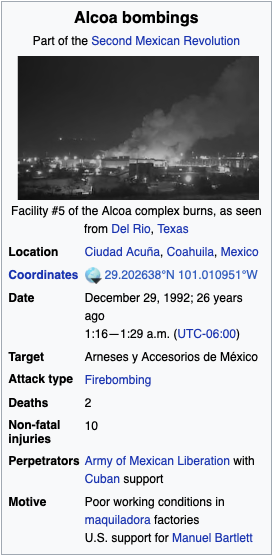

Part 19: Alcoa bombings

Arneses y Accesorios de México was the archetypal example of a maquiladora. Located within spitting distance of Texas in the Mexican border state of Coahuila, the enormous complex of eight factories had been built in 1982 by the Pittsburgh-based aluminum conglomerate Alcoa, so that it could manufacture its products for the U.S. market without having to worry about such pesky little things as taxes, health codes or a minimum wage. Though it was only one of thousands foreign-owned plants south of the Rio Grande, the Alcoa complex was a prime example of the exploitation which Mexican workers faced at the hands of American businesses: Alcoa’s assembly-line employees were paid subsistence-level wages that forced them to live in extreme poverty, sleeping in cardboard boxes and defecating in backyard latrines that left entire neighborhoods reeking of human excrement. Alcoa’s American managers, meanwhile, commuted daily from the border town of Del Rio, Texas, where they enjoyed the relative luxuries of unpolluted drinking water, paved roads and a functioning sewer system. Of the 60 factories in the border city of Acuña (itself little more than a squalid grid of dirt streets lined by taverns and whorehouses), Alcoa’s was by far the largest, employing well over 5,000 Mexicans to produce hundreds of miles of aluminum wire every day. It was perhaps its size and its perfect embodiment of the ugly side of capitalism that made Arneses y Accesorios de México such a tempting target.

At approximately 1:16 in the morning on December 29, 1992, residents of both Acuña and Del Rio were awoken from their slumber by a deafening boom. When they looked in the direction of the Alcoa complex, they were stunned to see one of the eight factories ablaze, casting a pillar of black smoke into the dark winter sky. Acuña hadn't had a functioning fire engine for years, and so the Del Rio Fire Department had to send several of its own trucks across the border to extinguish the blaze. [1] By the time they arrived, additional bombs had gone off in two more factories. Despite the firefighters’ efforts, neither of the two facilities could be saved; millions of dollars’ worth of industrial machinery and equipment were destroyed. No one had been in the factories when the bombs went off, but ten Mexicans suffered severe burns when floating embers spread the fire to a nearby cluster of shacks.

On December 30, an Acuña-based cell of the Army of Mexican Liberation (which by this point had no connection to the Zapatista ELM apart from the name) claimed responsibility for the bombings, calling them an “act of retaliation” against American big business for its “exploitative, capitalistic practices”, and against the Bush administration for its support of the “tyranno-fascistic” Manuel Bartlett. No one was surprised when the Cuban government declined to issue a formal condemnation to the bombings—indeed, by the time Cuba emerged from its “Special Period” in 1992, most ELM cells outside the State of Zapata had all but disappeared from lack of interest from their patron. Indeed, in his 2004 report on the organization, Senator Samuel del Villar hypothesized that Havana targeted the Alcoa complex primarily because the Acuña cell was one of the only ELM circles still in operation by late 1992.

Public reactions to the Alcoa bombings were decidedly subdued. Certainly no Mexican was particularly sorry to see the factories destroyed, and because no American citizens had been harmed in the bombing (all the American staff had been safe and snug in their Texan beds), only the most die hard of Washington war hawks called for any sort of direct military intervention. Indeed, after the New York Times published an article in the wake of the bombing which described Alcoa workers’ appalling living conditions in vivid detail, many Americans began to sympathize with the perpetrators of the bombing, agreeing with their motives if not their methods. As American newspapers filled their pages with stories of leaking industrial fumes that caused one hundred workers to be hospitalized, and of janitors being posted inside factory bathrooms to make sure workers used no more than three sheets of toilet paper per visit, [2] the fount of public outrage was turned upon Alcoa, and consumer groups began threatening a public boycott unless the company agreed to improve working conditions in its factories.

This put Alcoa in a very difficult position. A conservative estimate put the cost of rebuilding the complex at $42 million; a few years prior it would have been well worth the expense to get the factories back up and running, but by late 1992, Arneses y Accesorios de Mexico was becoming less and less profitable by the month. Alcoa had first built the complex ten years prior in order to take advantage of Acuña’s tax-free business environment, but since 1989, Manuel Bartlett had pressured the city government into levying all manner of new taxes in order to raise money for the eternally cash-strapped federal government. Shipping the manufactured goods back into the United States had once been a breeze, but ever since the intensification of the Drug War, all sorts of new regulations had been placed on incoming cargo which turned the entire transportation process into a convoluted, costly hassle. The bombings made things even more difficult: shareholders were now requesting that all Mexican employees be vetted for ELM sympathies before returning to work, while much of the American managerial staff had quit and the rest were demanding hefty pay raises to continue thoroughly coming to work. By mid-January, Alcoa’s board of directors became bitterly split between those who wanted to pay the price and keep the plant running, and those who wanted to cut their losses and abandon the complex entirely. Fortunately for them, however, a third option would soon emerge that would allow the company to save face and capital while also sidestepping the twin threats of boycotts and further terrorist attacks.

Paul O’Neill, the CEO of Alcoa, was steadfastly against the sale of the Acuña complex, and when the board of directors voted to sell it anyway, O’Neill resigned in protest. Lucky for him, he already had another job offer lined up: Secretary of Defense. President Bush, fed up with Secretary Dick Cheney’s constant warmongering vis-à-vis Mexico, nominated O’Neill as replacement within the first month of his second term, and he was confirmed by the Senate after two weeks of hearings. [3]

Even before the depression of 1988, Carlos Slim Helú had been a very rich man. But by 1992, Slim's wealth was reaching heights he would scarcely have dreamed possible just a few years before. The Salinas brothers’ frantic privatization campaigns had allowed him to buy several state-owned companies, which had turned near-immediate profits and made Slim one of the richest men in Mexico. One purchase that had not turned out to be particularly profitable, however, was the Compañía Minera de Cananea. After the government’s attempt to privatize the Sonora copper mine in 1990 had ended in massacre, [4] the Lesser Salinas had offered the mine to Slim at one-tenth its value just to get the mess off his hands. And, although the miners’ union had been surprisingly cooperative since Slim’s takeover (thanks largely to a contract in which Slim had agreed to invest heavily in education and infrastructure for the people of Cananea), profits for the mine remained disappointingly low. After the Alcoa bombings, however, Slim realized that if he could take over the Alcoa plant’s metalworking facilities, he would effectively gain control of the entire supply chain by extracting copper from his own mines, processing it in his own factories and shipping it to the United States with his own fleet of eighteen-wheelers. Delighted at the prospect of a vertical monopoly, Slim quickly made Alcoa an offer to buy the damaged complex for $92 million, hoping to get the paperwork signed by the weekend and have the factories up and running again by March.

But Slim's "easy" catch turned out not to be so easy. Less than two days after Slim made his offer, the young magnate Ricardo Salinas Pliego (who had bought the SICARTSA steel mill from the federal government earlier in the year) [5] swept in offering $102 million. Enraged, Slim quickly upped his offer to $108 million, prompting Salinas to raise his to $112 million. Within four weeks, Slim seemed to have won the corporate arms race with a $119 million offer that Salinas was hesitant to match. This made it all the more surprising when, on February 18, a labor union calling itself the Comité Fronterizo de Obreras (Border Workers' Committee, or CFO), announced very publicly and very loudly that it represented Alcoa’s employees in Acuña, and added that if it was not included in the negotiations, whoever ended up buying the complex would have a very tough time indeed getting it up and running again. [6]

Six years before, this would have been unthinkable. For decades, Acuña had been a union-free city. Even Mexico's "official" labor movement, the CTM, had only ever reared its head in order to prevent local workers from organizing by disrupting factory meetings with swarms of hired goons. By early 1993, however, the CTM's power had atrophied so much in the border regions that the Acuña branch could scarcely mobilize enough hired goons for a single decent game of lotería, and was all but powerless to quash the CFO. President Bartlett, for his part, was appalled at this insolent defiance of PRI authority, and was sorely tempted to have his Labor Secretary, Elba Esther Gordillo, declare the CFO an illegal union and imprison its leaders for operating without a federal charter. He relented, however, on the joint request of—surprisingly enough—none other than Carlos Slim and Ricardo Salinas Pliego.

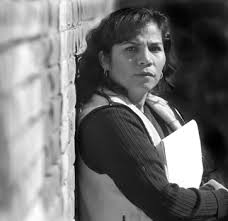

Most outside observers were stunned to see business magnates rallying so decisively to the defense of organized labor. But Slim and Salinas Pliego both had a good reason to support fair treatment of the CFO: labor relations at Slim’s copper mine and at Salinas Pliego’s steel mill had hitherto been harmonious, but only because of the generous contracts that each billionaire had signed with the unions which promised fair wages and reasonable hours. These unions were watching the Alcoa negotiations very closely, threatening to declare a solidarity strike if they got the impression that either billionaire was treating the CFO unfairly. Thus, Slim and Salinas, despite their mutual dislike, sensed that they would both be better off inviting the upstart CFO, led by the young but fiery labor activist Julia Quiñonez, [7] to negotiate in late February in the Coahuilan capital of Saltillo.

A single mother with a tireless energy for grassroots organizing, Acuña native Julia Quiñonez knew the conditions in maquiladora factories very well because she had worked in several of them as a teenager to finance her university studies. She had been in charge of the CFO for less than a year when the Alcoa bombings happened, but she knew a good opportunity when she saw one, and within two months, Quiñonez had succeeded in uniting all of Alcoa’s employees under the CFO banner and securing a role for the union in the negotiations for the sale of the Acuña complex.

At the negotiations Quiñonez and her associate Juan Tovar wasted no time laying out their demands: its members would refuse to return to work unless Slim or Salinas agreed to a contract promising ample wages and significant investment in Acuña’s local infrastructure. Many observers within the American business community doubted that the CFO would get very far, believing that either Slim or Salinas would simply buy the complex outright from Alcoa and then replace all the unionized workers with unemployed locals. But this was not an option for either billionaire, because both Slim’s copper miners and Salinas’s steel workers were watching the negotiations very carefully for any excuse to strike; this resulted in a highly bizarre situation in which two business magnates were pitted against one another in fierce competition to see which one could spend more to create safe and comfortable conditions for his workers. Finally, after two weeks of increasingly generous offers from both magnates, Quiñonez announced that the CFO had agreed to a contract with Salinas which included a 40-hour work week and a minimum hourly wage of ten pesos, [8] as well as to construct housing for employees, finance improvements to Acuña’s sewage infrastructure and even build a new school for the city’s youth. To make up for these concessions, Salinas reduced his offer to Alcoa to $81 million; the company tried to persuade Carlos Slim to buy the complex at his original price, but an irritated Slim rescinded his offer, seeing no point in buying the factory if no one would agree to work in it. The board of directors reluctantly sold the company to Salinas in March, and production resumed the following month.

In Acuña, the outcome of the talks was celebrated as an enormous victory for the city’s workers, and Quiñonez and Tovar returned home to find they were being revered as heroes. Within a month, the CFO had gained footholds in 39 of Acuña’s 60 maquiladoras, representing tens of thousands of residents and causing several American corporations—most notably AlliedSignal and General Electric—to flee Acuña for the same reasons as Alcoa. The rapid divestments attracted further interest from Mexican magnates, including Slim (who finally acquired a complex of his own in May) and Kamel Nacif Borge, who continually competed for the favor of the newly-unionized workers. The companies which decided not to sell, meanwhile, had little choice but to revise their contracts to prevent labor unrest. By the end of 1993, average wages in Acuña had more than doubled thanks to CFO pressure, and the union had secured a long list of municipal improvements, including a renovation of much of the impoverished city’s sewage infrastructure, expansion of the city’s forty-five-bed health clinic into a two-story, general hospital, as well as the construction of over three dozen residential housing blocks, two schools, a functioning fire station and a public library—a collective investment of well over one billion pesos.

President Bartlett tried to keep the CFO’s successes a secret by pressuring border state newspapers into dropping it from their columns. But he couldn’t keep the union isolated for long, especially as Juan Tovar and other CFO representatives began traveling from city to city to organize workers throughout the entire border region. By May, independent unions had been formed in Matamoros, Piedras Negras, Chihuahua and Ciudad Juárez. However, these unions were severely hampered by the fact that they did not possess a federal registro, or charter, meaning that if they ever tried to take industrial action, they would be declared illegal by PRI-controlled labor tribunals. The major breakthrough for the CFO came when Tovar and his colleagues arrived at the Korean-owned Han Young truck chassis plant in Tijuana, whose workers had already formed an independent union affiliated with the Frente Autentico de Trabajo, or FAT, one of the only non-PRI-affiliated labor federations in Mexico. Though strapped for cash and under constant persecution by PRI authorities, the FAT had experienced legal staff and—most vitally—a government registro. Combining the FAT’s legitimacy and legal prowess with the CFO’s talent for organization and publicity, the Han Young workers were able to extract a new contract from their Korean bosses which promised higher wages and fewer working hours. As the CFO’s first major success outside Acuña, the victory was consequential enough that, in June, the two organizations decided to formally merge, bringing the CFO’s border syndicates in line with the FAT’s widely-scattered unions and forming the basis for an independent, grassroots labor movement which was rising to take the place of the CTM. And, as Coahuila’s triennial statewide elections approached in September, Quiñonez led the FAT’s Acuña branch into an alliance with Alianza Civica, Sergio Aguayo’s pro-democracy movement, in hopes of defying PRI authority and electing an opposition governor for only the second time in recent Mexican history.

Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, the leading opposition voice in the Senate (even though there was barely any more opposition to lead), was especially piqued when Labor Secretary Elba Esther Gordillo revoked the FAT’s registro, because he himself had granted them their first registro in 1974 while serving as President Luis Echeverría's Labor Secretary. A week after the revocation, Senator Muñoz Ledo gave a long and blistering speech in the Senate chamber in which he called it “a gross and unjust violation of constitutional labor rights”.

President Bartlett, naturally, was almost paralyzed in fear of this threat to PRI hegemony. On his orders, Labor Secretary Elba Esther Gordillo revoked the FAT’s registro, turning it into an illegal union. In response, opposition Senator Porfirio Muñoz Ledo—who himself had served as Labor Secretary under President Luis Echeverría Álvarez, and had granted the FAT its registro in 1974—gave a long speech on the Senate floor condemning the revocation as a violation of labor rights. President Bartlett also ordered Fidel Velázquez, the 92-year-old, borderline-senile Secretary-General of the CTM, to suppress all attempts at independent organization. And when the oficialista unions proved too weak in many places to accomplish this task, Bartlett simply directed his security forces to harass, arrest, assault, pummel, pound, and otherwise disrupt the activities of independent labor organizers. Yet even the DFS was distracted in carrying out this mission by its dogged campaign against the Tijuana Cartel.

In December of 1992, twelve of the DFS’s most seasoned operatives were sent to Tijuana, where they worked undercover for three months, tapping phones, identifying traffickers, observing the patterns and laying the groundwork for a decisive blow against the infamous Tijuana Cartel—the organization headed by the Arellano Félix brothers which dominated the trade of cocaine, heroin, marijuana and methamphetamine all along the Pacific coast. Finally, on March 12, 1993, the Governor of Baja California, Daniel Quintero Peña, publicly announced that he had invoked the Law of Regional Security and formally requested DFS assistance in dealing with the Cartel problem. Within two hours of the announcement, DFS agents assassinated Benjamin Arellano Félix by hemming his convoy of armored cars into a narrow street and destroying his car with an anti-tank rocket. Over the next few days, half a dozen of the Cartel’s comandantes were shot by DFS troops while the surviving Arellano Félix brother, Ramón, slunk from safehouse to safehouse to avoid capture. Despite the deaths of most of its leaders, however, the Cartel responded quickly to the surprise attack, digging in and fighting brutally to defend their turf; by the end of March, the DFS claimed to have killed or arrested more than forty Cartel members, and yet in that time it suffered nineteen casualties among its own ranks.

Nevertheless, by May the Arellano Félix organization had been driven out of Tijuana. Ramón Arellano Félix was forced to flee south with his remaining manpower to Sinaloa, where he quickly came into conflict with La Alianza de Sangre, a rival cartel controlled by Héctor Luis Palma and Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. American observers were initially astonished at the rapidity with which the DFS drove out the Tijuana Cartel, but the amazement soon turned into skepticism as drug abuse rates quickly rose back to their previous levels; Washington didn’t know it yet, but it would eventually be revealed that the entire operation had been financed by the drug lord Miguel Caro Quintero so that his Sonora Cartel could take over Tijuana. The DFS agents who remained in the city soon began taking generous cuts of the Sonora Cartel’s flourishing profits in exchange for their help in transporting drugs across the border. The Army, meanwhile, looked upon this arrangement with the green eye of envy. In decades past, the Army had profited immensely off the drug trade with minimal competition, and thousands of officers had built their entire careers around this lucrative source of wealth. Now, entire battalions were being forced through humiliating “retraining” regimens just so that they could spend months camping outside Zapatista ratholes in a mosquito-infested jungle, while Bartlett ensured his pretty boys in the DFS grew rich and fat off drug money that rightfully belonged to the Army.

Several of the Army’s most prominent leaders, including Generals Alfredo Navarro Lara, Horacio Montenegro and Jesus Gutiérrez Rebollo, were growing sorely resentful of President Bartlett. For the moment, though, they would have little time to reflect on their grievances because a renewed push was being planned against the State of Zapata. Abandoning conventional approaches, the Defense Secretariat had designed a new offensive which would isolate the rebellious communities and force them to surrender, all while avoiding the large-scale maneuvers which had led to the disaster at San Cristóbal the previous year. On April 4, the Army marched once again into Zapatista territory, intending to put an end to the rebellion once and for all and force the ELM rebels back under Mexico City's firm and unforgiving rule.

[2] Both actual things that Alcoa’s Mexican workers had to contend with, and most likely still do.

[3] In OTL as well as TTL, Bush the Elder offered O’Neill the post of Secretary of Defense in 1988, but he declined. In OTL, O’Neill would eventually serve in the Cabinet as Bush the Younger's Treasury Secretary.

[4] See Part Twelve!

[5] In OTL, SICARTSA was sold to a steel conglomerate in 1991 for $22 million.

[6] The CFO is an actual organization, formed before TTL’s POD. They have a website which is available in both Spanish and English, though it hasn’t been updated in a very long time.

[7] Quiñonez was a leader of the CFO in real life, and in 1996 she helped arrange for Juan Tovar to go to Alcoa’s annual meeting in Pittsburgh in order to publicly call out Paul O’Neill on the horrible working conditions in front of a convention full of shareholders.

[8] A marked improvement over the three-peso-an-hour, 48-hour work weeks Alcoa workers faced in OTL 1993.

At approximately 1:16 in the morning on December 29, 1992, residents of both Acuña and Del Rio were awoken from their slumber by a deafening boom. When they looked in the direction of the Alcoa complex, they were stunned to see one of the eight factories ablaze, casting a pillar of black smoke into the dark winter sky. Acuña hadn't had a functioning fire engine for years, and so the Del Rio Fire Department had to send several of its own trucks across the border to extinguish the blaze. [1] By the time they arrived, additional bombs had gone off in two more factories. Despite the firefighters’ efforts, neither of the two facilities could be saved; millions of dollars’ worth of industrial machinery and equipment were destroyed. No one had been in the factories when the bombs went off, but ten Mexicans suffered severe burns when floating embers spread the fire to a nearby cluster of shacks.

On December 30, an Acuña-based cell of the Army of Mexican Liberation (which by this point had no connection to the Zapatista ELM apart from the name) claimed responsibility for the bombings, calling them an “act of retaliation” against American big business for its “exploitative, capitalistic practices”, and against the Bush administration for its support of the “tyranno-fascistic” Manuel Bartlett. No one was surprised when the Cuban government declined to issue a formal condemnation to the bombings—indeed, by the time Cuba emerged from its “Special Period” in 1992, most ELM cells outside the State of Zapata had all but disappeared from lack of interest from their patron. Indeed, in his 2004 report on the organization, Senator Samuel del Villar hypothesized that Havana targeted the Alcoa complex primarily because the Acuña cell was one of the only ELM circles still in operation by late 1992.

Public reactions to the Alcoa bombings were decidedly subdued. Certainly no Mexican was particularly sorry to see the factories destroyed, and because no American citizens had been harmed in the bombing (all the American staff had been safe and snug in their Texan beds), only the most die hard of Washington war hawks called for any sort of direct military intervention. Indeed, after the New York Times published an article in the wake of the bombing which described Alcoa workers’ appalling living conditions in vivid detail, many Americans began to sympathize with the perpetrators of the bombing, agreeing with their motives if not their methods. As American newspapers filled their pages with stories of leaking industrial fumes that caused one hundred workers to be hospitalized, and of janitors being posted inside factory bathrooms to make sure workers used no more than three sheets of toilet paper per visit, [2] the fount of public outrage was turned upon Alcoa, and consumer groups began threatening a public boycott unless the company agreed to improve working conditions in its factories.

This put Alcoa in a very difficult position. A conservative estimate put the cost of rebuilding the complex at $42 million; a few years prior it would have been well worth the expense to get the factories back up and running, but by late 1992, Arneses y Accesorios de Mexico was becoming less and less profitable by the month. Alcoa had first built the complex ten years prior in order to take advantage of Acuña’s tax-free business environment, but since 1989, Manuel Bartlett had pressured the city government into levying all manner of new taxes in order to raise money for the eternally cash-strapped federal government. Shipping the manufactured goods back into the United States had once been a breeze, but ever since the intensification of the Drug War, all sorts of new regulations had been placed on incoming cargo which turned the entire transportation process into a convoluted, costly hassle. The bombings made things even more difficult: shareholders were now requesting that all Mexican employees be vetted for ELM sympathies before returning to work, while much of the American managerial staff had quit and the rest were demanding hefty pay raises to continue thoroughly coming to work. By mid-January, Alcoa’s board of directors became bitterly split between those who wanted to pay the price and keep the plant running, and those who wanted to cut their losses and abandon the complex entirely. Fortunately for them, however, a third option would soon emerge that would allow the company to save face and capital while also sidestepping the twin threats of boycotts and further terrorist attacks.

Paul O’Neill, the CEO of Alcoa, was steadfastly against the sale of the Acuña complex, and when the board of directors voted to sell it anyway, O’Neill resigned in protest. Lucky for him, he already had another job offer lined up: Secretary of Defense. President Bush, fed up with Secretary Dick Cheney’s constant warmongering vis-à-vis Mexico, nominated O’Neill as replacement within the first month of his second term, and he was confirmed by the Senate after two weeks of hearings. [3]

Even before the depression of 1988, Carlos Slim Helú had been a very rich man. But by 1992, Slim's wealth was reaching heights he would scarcely have dreamed possible just a few years before. The Salinas brothers’ frantic privatization campaigns had allowed him to buy several state-owned companies, which had turned near-immediate profits and made Slim one of the richest men in Mexico. One purchase that had not turned out to be particularly profitable, however, was the Compañía Minera de Cananea. After the government’s attempt to privatize the Sonora copper mine in 1990 had ended in massacre, [4] the Lesser Salinas had offered the mine to Slim at one-tenth its value just to get the mess off his hands. And, although the miners’ union had been surprisingly cooperative since Slim’s takeover (thanks largely to a contract in which Slim had agreed to invest heavily in education and infrastructure for the people of Cananea), profits for the mine remained disappointingly low. After the Alcoa bombings, however, Slim realized that if he could take over the Alcoa plant’s metalworking facilities, he would effectively gain control of the entire supply chain by extracting copper from his own mines, processing it in his own factories and shipping it to the United States with his own fleet of eighteen-wheelers. Delighted at the prospect of a vertical monopoly, Slim quickly made Alcoa an offer to buy the damaged complex for $92 million, hoping to get the paperwork signed by the weekend and have the factories up and running again by March.

But Slim's "easy" catch turned out not to be so easy. Less than two days after Slim made his offer, the young magnate Ricardo Salinas Pliego (who had bought the SICARTSA steel mill from the federal government earlier in the year) [5] swept in offering $102 million. Enraged, Slim quickly upped his offer to $108 million, prompting Salinas to raise his to $112 million. Within four weeks, Slim seemed to have won the corporate arms race with a $119 million offer that Salinas was hesitant to match. This made it all the more surprising when, on February 18, a labor union calling itself the Comité Fronterizo de Obreras (Border Workers' Committee, or CFO), announced very publicly and very loudly that it represented Alcoa’s employees in Acuña, and added that if it was not included in the negotiations, whoever ended up buying the complex would have a very tough time indeed getting it up and running again. [6]

Six years before, this would have been unthinkable. For decades, Acuña had been a union-free city. Even Mexico's "official" labor movement, the CTM, had only ever reared its head in order to prevent local workers from organizing by disrupting factory meetings with swarms of hired goons. By early 1993, however, the CTM's power had atrophied so much in the border regions that the Acuña branch could scarcely mobilize enough hired goons for a single decent game of lotería, and was all but powerless to quash the CFO. President Bartlett, for his part, was appalled at this insolent defiance of PRI authority, and was sorely tempted to have his Labor Secretary, Elba Esther Gordillo, declare the CFO an illegal union and imprison its leaders for operating without a federal charter. He relented, however, on the joint request of—surprisingly enough—none other than Carlos Slim and Ricardo Salinas Pliego.

Most outside observers were stunned to see business magnates rallying so decisively to the defense of organized labor. But Slim and Salinas Pliego both had a good reason to support fair treatment of the CFO: labor relations at Slim’s copper mine and at Salinas Pliego’s steel mill had hitherto been harmonious, but only because of the generous contracts that each billionaire had signed with the unions which promised fair wages and reasonable hours. These unions were watching the Alcoa negotiations very closely, threatening to declare a solidarity strike if they got the impression that either billionaire was treating the CFO unfairly. Thus, Slim and Salinas, despite their mutual dislike, sensed that they would both be better off inviting the upstart CFO, led by the young but fiery labor activist Julia Quiñonez, [7] to negotiate in late February in the Coahuilan capital of Saltillo.

A single mother with a tireless energy for grassroots organizing, Acuña native Julia Quiñonez knew the conditions in maquiladora factories very well because she had worked in several of them as a teenager to finance her university studies. She had been in charge of the CFO for less than a year when the Alcoa bombings happened, but she knew a good opportunity when she saw one, and within two months, Quiñonez had succeeded in uniting all of Alcoa’s employees under the CFO banner and securing a role for the union in the negotiations for the sale of the Acuña complex.

At the negotiations Quiñonez and her associate Juan Tovar wasted no time laying out their demands: its members would refuse to return to work unless Slim or Salinas agreed to a contract promising ample wages and significant investment in Acuña’s local infrastructure. Many observers within the American business community doubted that the CFO would get very far, believing that either Slim or Salinas would simply buy the complex outright from Alcoa and then replace all the unionized workers with unemployed locals. But this was not an option for either billionaire, because both Slim’s copper miners and Salinas’s steel workers were watching the negotiations very carefully for any excuse to strike; this resulted in a highly bizarre situation in which two business magnates were pitted against one another in fierce competition to see which one could spend more to create safe and comfortable conditions for his workers. Finally, after two weeks of increasingly generous offers from both magnates, Quiñonez announced that the CFO had agreed to a contract with Salinas which included a 40-hour work week and a minimum hourly wage of ten pesos, [8] as well as to construct housing for employees, finance improvements to Acuña’s sewage infrastructure and even build a new school for the city’s youth. To make up for these concessions, Salinas reduced his offer to Alcoa to $81 million; the company tried to persuade Carlos Slim to buy the complex at his original price, but an irritated Slim rescinded his offer, seeing no point in buying the factory if no one would agree to work in it. The board of directors reluctantly sold the company to Salinas in March, and production resumed the following month.

In Acuña, the outcome of the talks was celebrated as an enormous victory for the city’s workers, and Quiñonez and Tovar returned home to find they were being revered as heroes. Within a month, the CFO had gained footholds in 39 of Acuña’s 60 maquiladoras, representing tens of thousands of residents and causing several American corporations—most notably AlliedSignal and General Electric—to flee Acuña for the same reasons as Alcoa. The rapid divestments attracted further interest from Mexican magnates, including Slim (who finally acquired a complex of his own in May) and Kamel Nacif Borge, who continually competed for the favor of the newly-unionized workers. The companies which decided not to sell, meanwhile, had little choice but to revise their contracts to prevent labor unrest. By the end of 1993, average wages in Acuña had more than doubled thanks to CFO pressure, and the union had secured a long list of municipal improvements, including a renovation of much of the impoverished city’s sewage infrastructure, expansion of the city’s forty-five-bed health clinic into a two-story, general hospital, as well as the construction of over three dozen residential housing blocks, two schools, a functioning fire station and a public library—a collective investment of well over one billion pesos.

President Bartlett tried to keep the CFO’s successes a secret by pressuring border state newspapers into dropping it from their columns. But he couldn’t keep the union isolated for long, especially as Juan Tovar and other CFO representatives began traveling from city to city to organize workers throughout the entire border region. By May, independent unions had been formed in Matamoros, Piedras Negras, Chihuahua and Ciudad Juárez. However, these unions were severely hampered by the fact that they did not possess a federal registro, or charter, meaning that if they ever tried to take industrial action, they would be declared illegal by PRI-controlled labor tribunals. The major breakthrough for the CFO came when Tovar and his colleagues arrived at the Korean-owned Han Young truck chassis plant in Tijuana, whose workers had already formed an independent union affiliated with the Frente Autentico de Trabajo, or FAT, one of the only non-PRI-affiliated labor federations in Mexico. Though strapped for cash and under constant persecution by PRI authorities, the FAT had experienced legal staff and—most vitally—a government registro. Combining the FAT’s legitimacy and legal prowess with the CFO’s talent for organization and publicity, the Han Young workers were able to extract a new contract from their Korean bosses which promised higher wages and fewer working hours. As the CFO’s first major success outside Acuña, the victory was consequential enough that, in June, the two organizations decided to formally merge, bringing the CFO’s border syndicates in line with the FAT’s widely-scattered unions and forming the basis for an independent, grassroots labor movement which was rising to take the place of the CTM. And, as Coahuila’s triennial statewide elections approached in September, Quiñonez led the FAT’s Acuña branch into an alliance with Alianza Civica, Sergio Aguayo’s pro-democracy movement, in hopes of defying PRI authority and electing an opposition governor for only the second time in recent Mexican history.

Porfirio Muñoz Ledo, the leading opposition voice in the Senate (even though there was barely any more opposition to lead), was especially piqued when Labor Secretary Elba Esther Gordillo revoked the FAT’s registro, because he himself had granted them their first registro in 1974 while serving as President Luis Echeverría's Labor Secretary. A week after the revocation, Senator Muñoz Ledo gave a long and blistering speech in the Senate chamber in which he called it “a gross and unjust violation of constitutional labor rights”.

President Bartlett, naturally, was almost paralyzed in fear of this threat to PRI hegemony. On his orders, Labor Secretary Elba Esther Gordillo revoked the FAT’s registro, turning it into an illegal union. In response, opposition Senator Porfirio Muñoz Ledo—who himself had served as Labor Secretary under President Luis Echeverría Álvarez, and had granted the FAT its registro in 1974—gave a long speech on the Senate floor condemning the revocation as a violation of labor rights. President Bartlett also ordered Fidel Velázquez, the 92-year-old, borderline-senile Secretary-General of the CTM, to suppress all attempts at independent organization. And when the oficialista unions proved too weak in many places to accomplish this task, Bartlett simply directed his security forces to harass, arrest, assault, pummel, pound, and otherwise disrupt the activities of independent labor organizers. Yet even the DFS was distracted in carrying out this mission by its dogged campaign against the Tijuana Cartel.

In December of 1992, twelve of the DFS’s most seasoned operatives were sent to Tijuana, where they worked undercover for three months, tapping phones, identifying traffickers, observing the patterns and laying the groundwork for a decisive blow against the infamous Tijuana Cartel—the organization headed by the Arellano Félix brothers which dominated the trade of cocaine, heroin, marijuana and methamphetamine all along the Pacific coast. Finally, on March 12, 1993, the Governor of Baja California, Daniel Quintero Peña, publicly announced that he had invoked the Law of Regional Security and formally requested DFS assistance in dealing with the Cartel problem. Within two hours of the announcement, DFS agents assassinated Benjamin Arellano Félix by hemming his convoy of armored cars into a narrow street and destroying his car with an anti-tank rocket. Over the next few days, half a dozen of the Cartel’s comandantes were shot by DFS troops while the surviving Arellano Félix brother, Ramón, slunk from safehouse to safehouse to avoid capture. Despite the deaths of most of its leaders, however, the Cartel responded quickly to the surprise attack, digging in and fighting brutally to defend their turf; by the end of March, the DFS claimed to have killed or arrested more than forty Cartel members, and yet in that time it suffered nineteen casualties among its own ranks.

Nevertheless, by May the Arellano Félix organization had been driven out of Tijuana. Ramón Arellano Félix was forced to flee south with his remaining manpower to Sinaloa, where he quickly came into conflict with La Alianza de Sangre, a rival cartel controlled by Héctor Luis Palma and Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán. American observers were initially astonished at the rapidity with which the DFS drove out the Tijuana Cartel, but the amazement soon turned into skepticism as drug abuse rates quickly rose back to their previous levels; Washington didn’t know it yet, but it would eventually be revealed that the entire operation had been financed by the drug lord Miguel Caro Quintero so that his Sonora Cartel could take over Tijuana. The DFS agents who remained in the city soon began taking generous cuts of the Sonora Cartel’s flourishing profits in exchange for their help in transporting drugs across the border. The Army, meanwhile, looked upon this arrangement with the green eye of envy. In decades past, the Army had profited immensely off the drug trade with minimal competition, and thousands of officers had built their entire careers around this lucrative source of wealth. Now, entire battalions were being forced through humiliating “retraining” regimens just so that they could spend months camping outside Zapatista ratholes in a mosquito-infested jungle, while Bartlett ensured his pretty boys in the DFS grew rich and fat off drug money that rightfully belonged to the Army.

Several of the Army’s most prominent leaders, including Generals Alfredo Navarro Lara, Horacio Montenegro and Jesus Gutiérrez Rebollo, were growing sorely resentful of President Bartlett. For the moment, though, they would have little time to reflect on their grievances because a renewed push was being planned against the State of Zapata. Abandoning conventional approaches, the Defense Secretariat had designed a new offensive which would isolate the rebellious communities and force them to surrender, all while avoiding the large-scale maneuvers which had led to the disaster at San Cristóbal the previous year. On April 4, the Army marched once again into Zapatista territory, intending to put an end to the rebellion once and for all and force the ELM rebels back under Mexico City's firm and unforgiving rule.

__________

[1] This was also the case by the OTL 1990s—Acuña had no functioning fire trucks and couldn’t afford to buy new ones or fix the ones they had, so Del Rio had to send in its own trucks to fight Mexican fires.

[2] Both actual things that Alcoa’s Mexican workers had to contend with, and most likely still do.

[3] In OTL as well as TTL, Bush the Elder offered O’Neill the post of Secretary of Defense in 1988, but he declined. In OTL, O’Neill would eventually serve in the Cabinet as Bush the Younger's Treasury Secretary.

[4] See Part Twelve!

[5] In OTL, SICARTSA was sold to a steel conglomerate in 1991 for $22 million.

[6] The CFO is an actual organization, formed before TTL’s POD. They have a website which is available in both Spanish and English, though it hasn’t been updated in a very long time.

[7] Quiñonez was a leader of the CFO in real life, and in 1996 she helped arrange for Juan Tovar to go to Alcoa’s annual meeting in Pittsburgh in order to publicly call out Paul O’Neill on the horrible working conditions in front of a convention full of shareholders.

[8] A marked improvement over the three-peso-an-hour, 48-hour work weeks Alcoa workers faced in OTL 1993.

Last edited:

But this post is about stuff that was bad OTL, and the big takeaway is Bartlett is overstretched and fails to prevent a bunch of workers from asserting their power to improve their circumstances. It is not clear to me how successful the regime was in for the moment preventing the union solution from being implemented immediately, but at any rate the workers have here demonstrated that product does not get made without them and that practical businessmen are perfectly capable of negotiating a fairer deal with them, whatever interventions the ATL tottering Mexican state tries to nullify them.Manlet Baruel needs to go.

Alcoa is out of Acuña. That at any rate is a done deal, and this is not just because terrorist blew up their plants, but because Mexican businessmen and Mexican grassroots worker organizations came to an accord, making the option of Alcoa staying the course (which was O'Neill's preferred policy) infeasible.

Note that O'Neill, the American CEO who is most personally responsible for the terrible conditions in the maquiladora, achieves the position of a US Federal Government Cabinet secretary under one or another President named Bush both OTL and in the ATL; Alcoa as a US company went right on profiting (with margins dwindling for reasons parallel to the ATL OTL I suppose, though not as precipitously) OTL, and in the ATL they pull in their horns with an 80 million dollar compensation package, no other harm done to them.

Bartlett is a bad actor, make no mistake. And what makes him bad is his prioritizing servicing the same interests that OTL ruled supreme and unchecked, in Mexico and in the USA.

Making this a story about Bartlett being a singular bad guy who singlehandedly makes Mexico worse is a pretty profound misreading of the story we have been given thus far. If anything I have been critical of the author and fans softpedaling Yanqui responsibility for Mexico's ills--those aren't solely made in the USA, but we aren't helping--nor were we OTL.

As long as the USA is a government of for and by men like O'Neill (and no, I can't say the Democratic alternative administrations between Bushes are not complicit too, though there are objective measurable differences, in these respects they are matters of degree not direction) Mexicans must overcome not only their own corruption but institutionalized and powerful US corruption too.

Shouldn't the conflict of interest involved in the suggestion by many fans that the proper resolution is US invasion, when the guy running the invading forces under GHW Bush's command would be the same guy who oversaw Arneses y Accesorios de México as part of his corporate fiefdom? Why would we expect US occupation to result in a better deal for Mexicans under such leadership, with such interests and track records in dealing with Mexican citizens on a smaller scale?

The difference between Bartlett and OTL was that OTL men like O'Neill made out better from a more successfully repressed Mexico. Bartlett has no good intentions and nothing redeeming him personally. He is not however the creator of the evils we see in this post, and his ATL success at rising to his level of incompetence where he fails to serve the interest of foreign corporate boards as successfully is actually possibly hopeful for the Mexican people in the longer run. He deserves jail time, lots of it, not medals.

But a lot more than this one person needs to "go." And they are not all Mexicans! It is not clear to me the outcome will not wind up being just another case of meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

President Bartlett is reading more and more like Cersei Lannister. Supremely confident and arrogant but stupid as hell.

Threadmarks

View all 42 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 23: Manuel Bartlett Díaz, Carlos Hank González Part 24: Salamanca disaster Part 25: 1996 United States presidential election, Democratic Hope, Christian Democratic Party, 1997 Mexican legislative elections Part 26: 1999 Mexican constitutional referendum, 2000 Mexican legislative elections, 2000 Mexican presidential election Epilogue Acknowledgments Selected World Leaders, 1988—2021 A Very Special Announcement

Share: