I've done a fair amount of rebooting and retconning over the years. I don't anticipate doing much more. But St Pierre had only a half-assed little blurb that obscured the uniquness of the islands, and that had to be fixed. What follows is more a geopolitical than a cultural history. I want to slend some time exploring the island's culture... but I'm planning a trip there in the nearish future. I know I'll write a lot more then. For now, we can think about what the islands' history reveals about the development of the ASB and its relationship to Europe.

I’d like to set some context first. As early as the 15th century the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon were an important base for fishermen from Normandy, Brittany, and the Basque Country. In the wars of the 18th century they passed back and forth between France and England. England repeatedly ordered the French settlers to be deported, but French fishing boats continued to frequent the islands. The conflicts over St. Pierre were part of the wider conflict over who controlled Newfoundland. In the treaty of 1808, England and the French Empire confirmed what was basically the status quo already: that Newfoundland would belong to England alone; that France would have exclusive fishing rights along part of the coast, but no territorial rights; and that France would possess the little islands so that it would have a toehold of land in the fishery.

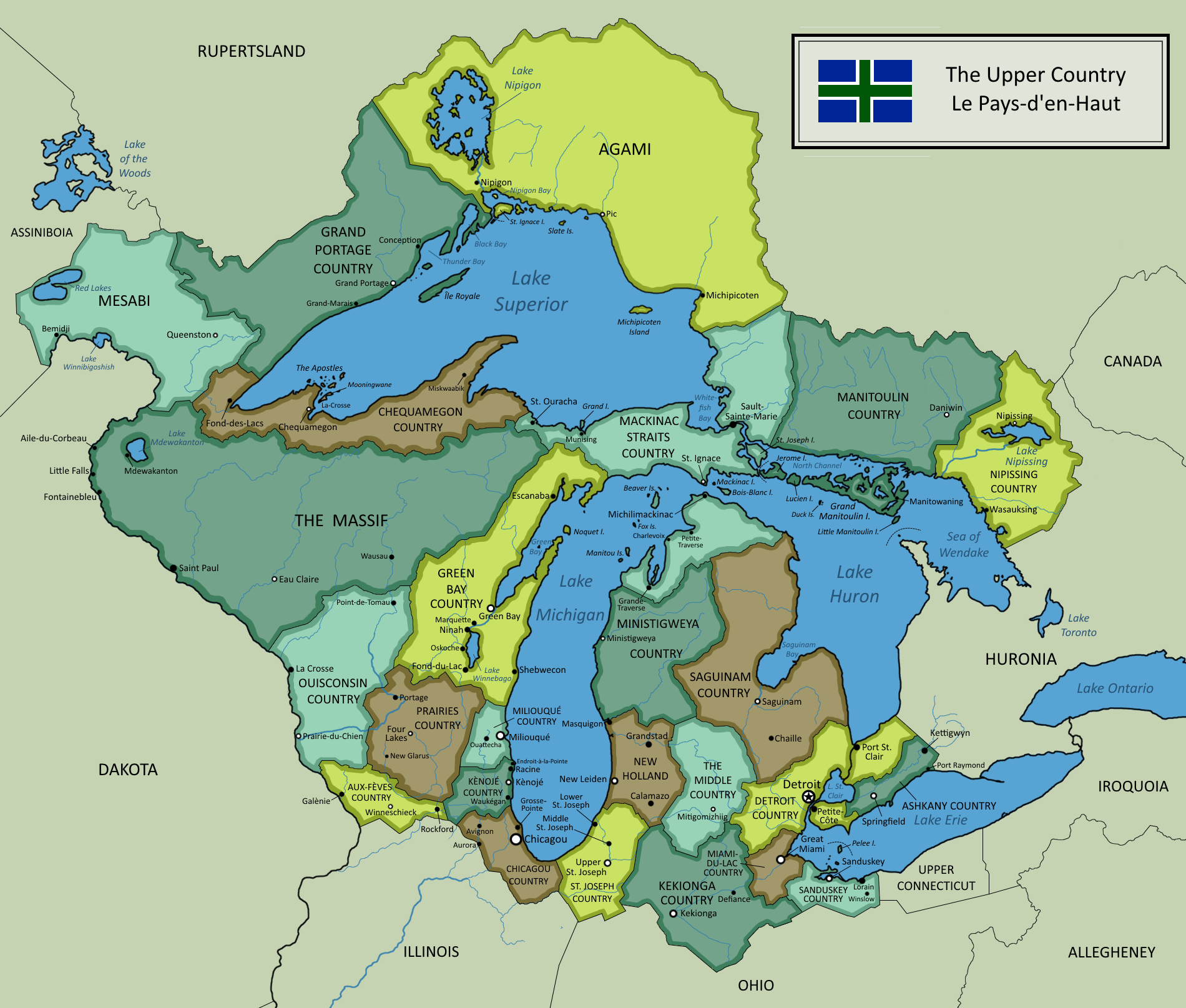

Napoleonic France came to an end in 1832 after the death of Napoleon II. The young emperor was childless but not heirless and had taken pains to set up an orderly succession; nevertheless, republican forces saw their opportunity. The revolution was bloody but short. In North America, the four parts of the Kingdom of New France also took the opportunity to shake off French rule. Once news of the revolution arrived, independence was declared in Canada, Louisiana, Illinois, and Saint-Domingue. The only northern colonies that France managed to hold were Acadia, which was not part of the Kingdom of New France, and St. Pierre and Miquelon.

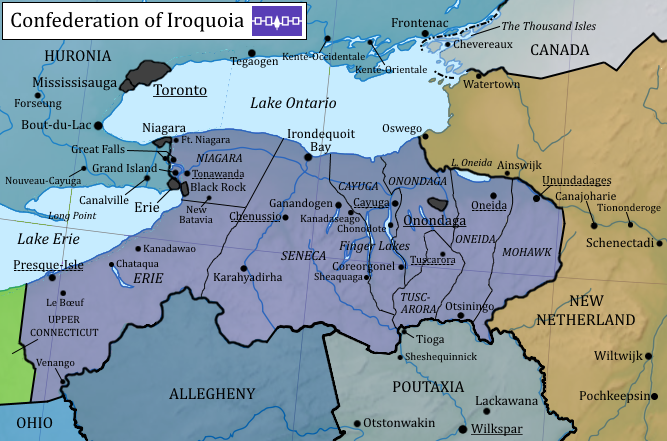

Years of dispute over the islands and the fisheries ensued between France and the new government of Canada. Canada considered itself the rightful successor to France and wanted to assume its role in the islands, the French Shore of Newfoundland, and Labrador. The dispute played out in the Congress of the Nations, which had emerged as the main deliberative body for all the Boreoamerican states. It remained unsolved in 1849 when Acadia, the last major French colony on the continent, declared its independence. The event sparked something of a crisis in Congress, since many delegates believed that some French presence was necessary to the continental balance of power. This faction was placated by a compromise that recognized St. Pierre and the French Shore rights as the property of the French Republic, not Canada. As compensation, Canada inherited France’s rights in Labrador.

St. Pierre’s status as the last French colony had economic and political consequences. The cod fishery was still valuable, and France was happy to keep its access to it even if it had lost its territorial colonies. And importantly for the ASB, the deal meant that a French delegation remained in Congress and would continue to have a voice in confederal affairs.

During this period, the population of the islands grew. Most of the newcomers came from the same regions that had supplied the earliest arrivals: Normandy, Brittany, and the French Basque Country. Smaller numbers of people arrived from nearby states; they included Newfoundlanders, Acadians, and Gaelic-speaking New Scots, resulting in a lively and unusual cultural mix. St. Pierre grew into a sizable town and received a proper government.

The evolving political structure of the ASB was giving more and more power to the elected Parliament. Congress, whose members were appointed by the state governments, including the French government of St. Pierre, faded into the background. The Parliament of 1868 is considered the first of the modern era, and in 1899 Congress was abolished as a legislative body. During these years the confederal government assumed control over member states’ military and foreign policy. France’s voice in the Congress became increasingly irrelevant.

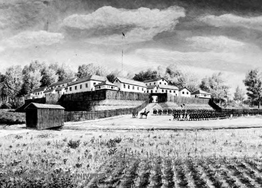

In the late 19th century there were still some questions over how much right the former colonial powers had in their loyal Boreoamerican dominions. Newfoundland and southern New England were still in a sense part of the English Empire, while Christiana still had ties to Sweden and, through personal union, to the Russian Empire. France’s sovereignty over St. Pierre was seen in the same light. Therefore, the great European war that erupted in the early 20th century presented the very real danger that the ASB could become a theater of European conflict. The confederation had been founded precisely to prevent this sort of thing. Parliament, under the control of the centralizing branch of the Whig Party, passed strongly worded resolutions that banned European warships from ASB waters and built up the navy and coastal defenses to enforce the ban. The ASB ended up joining the war anyway, but the ban was upheld in subsequent treaties.

This meant that while St. Pierre remained part of the French Republic in name, in fact it was an integral part of the ASB. The islands had not had representation in Parliament before due to their very small population, never more than 10,000. Now they sought a status equal to the other states. They were recognized as a state in 1925. France had to begrudgingly accept its reduced role in the islands and enacted laws that loosened ties to St. Pierre and created an autonomous state government.

St. Pierre and Miquelon officially remained a French overseas territory, but France’s power was strictly circumscribed by a body of laws and treaties. French fishing fleets continued to come to the islands and to Newfoundland, but boats from the rest of the ASB were free to fish as well. French law applied somewhat, but acts of the ASB’s parliament took precedence, as St. Pierre was first and foremost an ASB state. The islanders today, though loyal citizens of the confederation, are still proud of the symbolic and economic links that they have with France. Their culture is more closely tied to Europe than the rest of Franco-America, and the state is a reminder of the legacy of the French overseas empire.

I’d like to set some context first. As early as the 15th century the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon were an important base for fishermen from Normandy, Brittany, and the Basque Country. In the wars of the 18th century they passed back and forth between France and England. England repeatedly ordered the French settlers to be deported, but French fishing boats continued to frequent the islands. The conflicts over St. Pierre were part of the wider conflict over who controlled Newfoundland. In the treaty of 1808, England and the French Empire confirmed what was basically the status quo already: that Newfoundland would belong to England alone; that France would have exclusive fishing rights along part of the coast, but no territorial rights; and that France would possess the little islands so that it would have a toehold of land in the fishery.

Napoleonic France came to an end in 1832 after the death of Napoleon II. The young emperor was childless but not heirless and had taken pains to set up an orderly succession; nevertheless, republican forces saw their opportunity. The revolution was bloody but short. In North America, the four parts of the Kingdom of New France also took the opportunity to shake off French rule. Once news of the revolution arrived, independence was declared in Canada, Louisiana, Illinois, and Saint-Domingue. The only northern colonies that France managed to hold were Acadia, which was not part of the Kingdom of New France, and St. Pierre and Miquelon.

Years of dispute over the islands and the fisheries ensued between France and the new government of Canada. Canada considered itself the rightful successor to France and wanted to assume its role in the islands, the French Shore of Newfoundland, and Labrador. The dispute played out in the Congress of the Nations, which had emerged as the main deliberative body for all the Boreoamerican states. It remained unsolved in 1849 when Acadia, the last major French colony on the continent, declared its independence. The event sparked something of a crisis in Congress, since many delegates believed that some French presence was necessary to the continental balance of power. This faction was placated by a compromise that recognized St. Pierre and the French Shore rights as the property of the French Republic, not Canada. As compensation, Canada inherited France’s rights in Labrador.

St. Pierre’s status as the last French colony had economic and political consequences. The cod fishery was still valuable, and France was happy to keep its access to it even if it had lost its territorial colonies. And importantly for the ASB, the deal meant that a French delegation remained in Congress and would continue to have a voice in confederal affairs.

During this period, the population of the islands grew. Most of the newcomers came from the same regions that had supplied the earliest arrivals: Normandy, Brittany, and the French Basque Country. Smaller numbers of people arrived from nearby states; they included Newfoundlanders, Acadians, and Gaelic-speaking New Scots, resulting in a lively and unusual cultural mix. St. Pierre grew into a sizable town and received a proper government.

The evolving political structure of the ASB was giving more and more power to the elected Parliament. Congress, whose members were appointed by the state governments, including the French government of St. Pierre, faded into the background. The Parliament of 1868 is considered the first of the modern era, and in 1899 Congress was abolished as a legislative body. During these years the confederal government assumed control over member states’ military and foreign policy. France’s voice in the Congress became increasingly irrelevant.

In the late 19th century there were still some questions over how much right the former colonial powers had in their loyal Boreoamerican dominions. Newfoundland and southern New England were still in a sense part of the English Empire, while Christiana still had ties to Sweden and, through personal union, to the Russian Empire. France’s sovereignty over St. Pierre was seen in the same light. Therefore, the great European war that erupted in the early 20th century presented the very real danger that the ASB could become a theater of European conflict. The confederation had been founded precisely to prevent this sort of thing. Parliament, under the control of the centralizing branch of the Whig Party, passed strongly worded resolutions that banned European warships from ASB waters and built up the navy and coastal defenses to enforce the ban. The ASB ended up joining the war anyway, but the ban was upheld in subsequent treaties.

This meant that while St. Pierre remained part of the French Republic in name, in fact it was an integral part of the ASB. The islands had not had representation in Parliament before due to their very small population, never more than 10,000. Now they sought a status equal to the other states. They were recognized as a state in 1925. France had to begrudgingly accept its reduced role in the islands and enacted laws that loosened ties to St. Pierre and created an autonomous state government.

St. Pierre and Miquelon officially remained a French overseas territory, but France’s power was strictly circumscribed by a body of laws and treaties. French fishing fleets continued to come to the islands and to Newfoundland, but boats from the rest of the ASB were free to fish as well. French law applied somewhat, but acts of the ASB’s parliament took precedence, as St. Pierre was first and foremost an ASB state. The islanders today, though loyal citizens of the confederation, are still proud of the symbolic and economic links that they have with France. Their culture is more closely tied to Europe than the rest of Franco-America, and the state is a reminder of the legacy of the French overseas empire.