You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A New World Wreathed in Freedom - An Argentine Revolution TL

- Thread starter minifidel

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 54 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Platine Naval Ensign Army of the United Provinces San Martin Conmemorative Bill 25 - Teetering on the Brink - The Web of Alliances in the stands of the 1910 Centennial Parade 26 - The United Provinces and the Great War 27 - The 1919 General Strike Left Radical Party (PRI) Infobox 28 - The Raging 20s and New Ingredients in the CauldronIt's interesting to see the consolidation of proper parties versus the equivalent of what Argentina had at the time (can't really speak for the other member countries of the UP but they probably weren't much better).

Though to be honest this all feels a little too democratic if you ask me. I know that there is a lot of room for interpretation and that the Cabildo system means things aren't as autocratic as OTL, but the people would not rule, the landowner and burgher classes would never allow it (and to be honest the peasant masses of the era wouldn't be that capable either if their descendants actions in the voting booth are anything to go by).

So it really feels somewhat strange to read democracy "working" when they are a loosely affiliated confederacy full of would be nobles and autocrats that would be perfectly at home in middle ages Europe or antebellum Southern US.

Except for that an interesting update and the creation of proper parties that are more than "I hate this guy" or "I support this guy" are s welcome development for the country, as it'll give them access to long term projects and increased stability (as long as they learn to play by the rules, I'm looking at you Juan Manuel "la Mazorca" de Rosas).

Well actually, what he is describing is esentially how the US worked at the time, and it is still labelled as democracy of some degree.

The key for liberal republicanism of the time is who gets to vote. In the Americas, the law usually set two requisites: being male, and a minimum anual rent. Besides, the ones in power unashamedly purged the voters roll.

On the other hand, compared to modern day Latin American democracies such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Costa Rica, among others, today's USA lacks behind in democratic qualifications, but no one disqualifies the USA from democratic, mainly for the bias of linking being a Western nation to being a democracy.

Uh, no? Unless I missed something the US has had their current system since day 1 and the Cabildo is in no way or form the Electoral college. If anything it has more in common with a parlamentary republic than it does with a presidential republic like the US.Well actually, what he is describing is esentially how the US worked at the time, and it is still labelled as democracy of some degree.

It' s more about the way it was phrased than the system itself. It reads too fully democratic while in truth it probably has more in common with Athenian democracy than it does with our current idea of it.The key for liberal republicanism of the time is who gets to vote. In the Americas, the law usually set two requisites: being male, and a minimum anual rent. Besides, the ones in power unashamedly purged the voters roll.

Eh, this is a really hot take if I ever saw one. I would hardly call Argentina more democratic than the US and if it is then please give me some of that autocracy because it's obviously superior.On the other hand, compared to modern day Latin American democracies such as Argentina, Uruguay, and Costa Rica, among others, today's USA lacks behind in democratic qualifications, but no one disqualifies the USA from democratic, mainly for the bias of linking being a Western nation to being a democracy.

Uh, no? Unless I missed something the US has had their current system since day 1 and the Cabildo is in no way or form the Electoral college. If anything it has more in common with a parlamentary republic than it does with a presidential republic like the US.

You are right.

It' s more about the way it was phrased than the system itself. It reads too fully democratic while in truth it probably has more in common with Athenian democracy than it does with our current idea of it.

You are right, but it is usual to label any non-monarchy as democracy. For me, what we deserve is an qualitative explanation of voting rights and how fair is the electoral roll made, given the vagueness of the word "democracy".

Eh, this is a really hot take if I ever saw one. I would hardly call Argentina more democratic than the US and if it is then please give me some of that autocracy because it's obviously superior.

I hardly think the US system, with its electoral college and its "one district - one representative", and how their districts are drawn, is in any way democratic. The US is, for me, a non-democratic federal constitutional republic.

The big difference between Platine "democracy" and American "democracy" at this point ITTL is that the United States is already well down the path of Jacksonian democracy, which did in fact significantly expand the franchise (to white men), while Platine elections resemble the UK's parliamentary elections (which did not involve casting secret ballots), mostly the fact that it's considered "democratic" despite the fact that the number of people who actually get to vote is small. To share a line of thought inspired by this discussion, I'm currently envisioning the chartist movement in the UK sending shockwaves through the United Provinces, which remain very plugged in to the United Kingdom and whose liberals openly cribbed off the British parliamentary system.

In a rural country with a developing infrastructure, having to travel to the Cabildo would in and of itself disenfranchise huge swathes of the population; the closest comparison to "getting people to the polls" would be gathering as many people in the Cabildo's square as possible while the Cabildo is in session to elect the delegates.

In a rural country with a developing infrastructure, having to travel to the Cabildo would in and of itself disenfranchise huge swathes of the population; the closest comparison to "getting people to the polls" would be gathering as many people in the Cabildo's square as possible while the Cabildo is in session to elect the delegates.

Last edited:

With any luck, the ideas I have should get me through to the 1840s at least, and I'm excited about the update I'm currently working on: we're going to be taking a step back from the United Provinces and look at the region again, but I wanted to tease the title and encourage y'all to speculate on the implications, heh.

Coming this Friday: The Incan Crisis.

Coming this Friday: The Incan Crisis.

With any luck, the ideas I have should get me through to the 1840s at least, and I'm excited about the update I'm currently working on: we're going to be taking a step back from the United Provinces and look at the region again, but I wanted to tease the title and encourage y'all to speculate on the implications, heh.

Coming this Friday: The Incan Crisis.

Incan Crisis? Oh no!

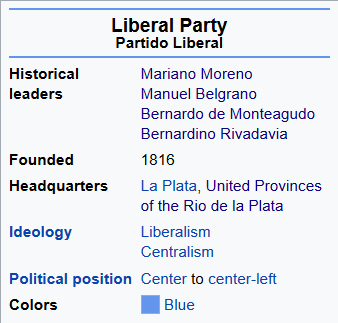

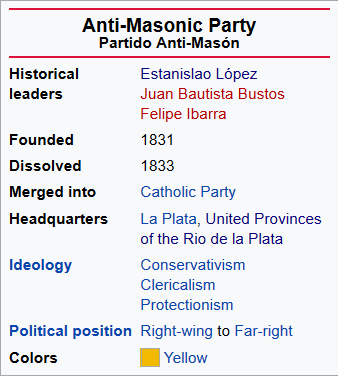

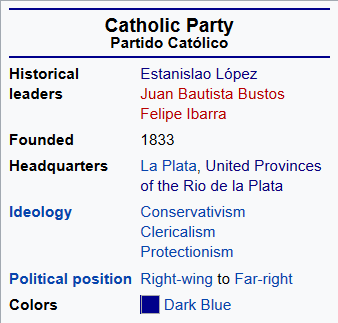

2nd Party System Infoboxes

I swear I'm not just procrastinating because writing civil wars is hard.

EDIT: And because I'm a cruel tease, I'm going to preemptively give a shout-out and thanks to @EMT, who deserves considerable credit for inspiring the upcoming chapter.

EDIT: And because I'm a cruel tease, I'm going to preemptively give a shout-out and thanks to @EMT, who deserves considerable credit for inspiring the upcoming chapter.

Last edited:

I don't think "right" and "left" are proper ways to divide political parties of the era, unless you were using the revolutionary Frech meaning of the terms...

That is pretty much it, yeah. The only one I actually modified though was the Federalist Party, which is originally marked as "center-right to right-wing". These are still not modern parties, they are very much products of their era.I don't think "right" and "left" are proper ways to divide political parties of the era, unless you were using the revolutionary Frech meaning of the terms...

Oh, and to continue teasing: the chapter is now in fact called "The Incan Crisis (Part 1)", so there's that.

16 - The Incan Crisis (Part 1)

Chapter 13 - The Incan Crisis (Part 1)

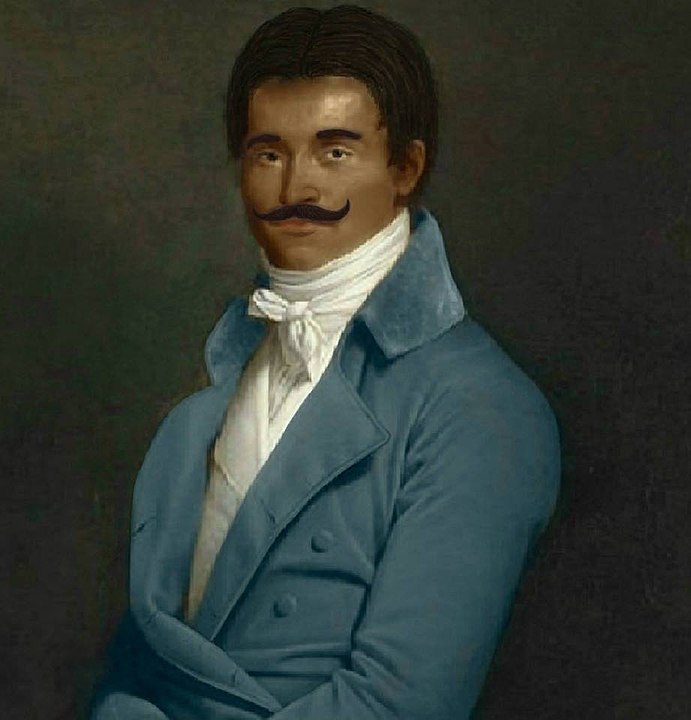

Tupác Amarú II, leader of the largest revolt against Spanish rule prior to the Independence Wars, was officially legitimized by the constitution of the Empire of the Incas.

1822 presented the supporters of an Incan monarchy in Perú a once in a lifetime opportunity: the revolutionaries at Cuzco believed wholeheartedly in an Incan restoration, and the Platine general leading the invasion to support Peruvian independence supported their goals. Belgrano’s government in La Plata also supported it, with the romantic image of a newly crowned Sapa Inka swearing to uphold a liberal constitution proving especially popular in the country.

But even as the revolutionary armies triumphed on the field of battle and marched into the viceroyal capital as liberators, resistance to a restoration started to form in Lima. Its criollos had a considerably less romantic view of the idea, and although they had little recourse as the proposal rode the wave of revolutionary fervor to a jubilant majority in the country’s first constitutional assembly, its critics met, made plans and waited. The two leading candidates for the throne were 75 and 61 years old with no known male issue, and they had secured at least that the capital would remain in Lima as a concession to their complaints, so Lima’s criollos celebrated as Juan Bautista Túpac Amarú - brother of the one-time pretender and rebel leader Túpac Amarú II - took the regnal name Túpac Amarú III.

Lima’s criollos even mourned upon his death in 1827, and greeted the coronation of a distant relative of an ancient Incan emperor with dignity. But Dionisio Inca Yupanqui, who would assume the regnal name Túpac Inca Yupanqui II, wasn’t just younger than his predecessor when he took the throne: he had been heavily involved in the Cuzco revolutionary government during the war, and had remained active in local politics. Above all, he was an outspoken champion of native rights, whose equality was legally enshrined in the new constitution but who continued to face discrimination and exploitation, especially in Lima and the criollo-dominated cities of the coast.

When he proposed to move the capital away from Lima in the inaugural address to Congress in 1830, most in Lima paid it little attention: the Sapa Inka had little power in the new constitution, and although he was popular among representatives - having served alongside most of them during the reign of Túpac Amarú III - Lima’s leaders had no reason to believe it was a serious possibility.

Until Yupanqui II supplemented his lobbying of his former colleagues with a bolder move, which agitated Lima’s elites because they realized with horror that they had no legal recourse against it: although his powers had originally been conceived as purely symbolic, Yupanqui quickly realized that his person held a symbolic power of its own, and he began to spend the time between congressional sessions at his private residence in Cusco. Rather than paralyze the government over what they all believed was a formality, most government ministers simply worked around this by either moving to Cusco themselves or travelling when necessary.

Most Limans tolerated it as long as Congress and the ministries remained located in the capital, but Yupanqui upped the ante in 1833 when he had a minor Incan noble elevated to co-ruler to designate him as heir and decided to hold the coronation in Cusco. When the imperial entourage left Lima en route to Cusco, accompanied by sympathetic ministers and members of Congress, Lima erupted into open rebellion: its Cabildo was stormed by armed criollos, and they’d seize control of the city after a bloody day of street battles with the native regiments of the garrison. The ferocious fighting ended with hundreds of native civilians killed in the crossfire, as the criollos marched through their quarters in pursuit of fleeing loyalists.

Túpac Inca Yupanqui II proved to be a consummate and skilled politician even after his coronation as Sapa Inca, sparking the ire of Lima's criollo elite.

The rebellion got off to a strong start, taking control of Lima and receiving reports of sympathetic rebellions in other coastal cities, but it stalled soon after when the rebels failed to sway any of the military leaders outside of the cities they controlled: the army had been created by José de San Martín while he commanded the Army of the Andes, and San Martín - sympathetic with the idea of an Incan restoration and still a popular figure in Perú - had staffed it with like minded officers in the highest ranks. The most prominent criollo generals like Luis José de Orbegoso broke with Lima, while José de la Riva-Agüero proclaimed neutrality, garrisoning his regiment in Jauja and frustrating their plan to proclaim one of them as provisional president of their fledgling republic.

The rebels would ultimately turn to another prominent Liman criollo, Pedro Pablo Bermúdez Ascarza, electing the commander of the Lima garrison as Provisional President of the Republic of Perú in recognition of his role in securing the support of the garrison’s criollo units. They had to move quickly, as Yupanqui II had made it to Cusco and was already in the process of gathering troops in the city to launch a counter-attack on Lima. Their capture of the Lima garrison’s stores gave them an edge in terms of artillery, but their troops were primarily composed of criollo militias with only a handful of professional regiments joining the rebellion openly.

It might have been a brief civil war, if not for an unexpected visit from the Colombian ambassador: Bolivar’s shadow still loomed large in Colombia, and he had instilled in the young nation both a fierce republicanism and an animosity towards San Martín and the Incan monarchy he had helped restore on its border. They also feared the prospect of a Platine-dominated coalition in South America, isolating Colombia from its revolutionary brethren. Desperate for support, the Liman rebels acquiesced to the ambassador’s conditions, and soon a secret treaty was struck between the republican government to secure Colombian “volunteers” for their cause.

Most importantly for the rebels, Colombia would secure the Peruvian navy for the republicans by paying off the foreign captains. This gave the Limans the ships they needed to ferry the 2,000 Colombian regulars Bogotá was willing to send, although they’d have to strip several of the ships of cannons to replace the artillery that had been spiked by fleeing loyalists. But this dangerous escalation of the conflict, with news of the treaty reaching Cusco only a week later, forced Yupanqui II to seek foreign support himself: appealing to his prior support for the cause of the Incan monarchy and his role as liberator of Perú, Yupanqui pleaded with San Martín to send aid to the Cuscan army and help him subdue the republican revolt while it was still in its infancy.

He found a receptive government in San Martín and Monteagudo, but both faced an uphill battle to convince the General Assembly to support the proposal. The rebranded Catholic Party flatly rejected the idea, while the Federalists balked at the idea of sending Platine soldiers to fight a foreign government’s civil war. 3 delegates short of a majority, Monteagudo could not convince the Assembly to approve funds for any expedition.

But sympathy for the Incan monarchy was incredibly strong in Collao, and Monteagudo would not desist: appealing as he had to win his election to Collaoan Federalists, the party’s leadership eventually agreed to a compromise. As a workaround to the Assembly’s hesitance to allocate funds to the cause, Monteagudo proposed to finance it with a special war bond instead. Heavily advertised in the Liberal press, the war bond would prove to be an unexpected hit, with Collao’s remaining Incan nobles - allowed to use their ancestral titles and properties even if stripped of their corresponding privileges - buying them in huge quantities.

For all the violence of the initial insurrection, the civil war sputtered to a stalemate quickly as both camps worked to secure outside help. Riva-Agüero had received orders from both Lima and Cuscco, but he still refused to pick a side, and his garrison stood in the way of both. Liman efforts to capture the ports of Arequipa were rebuffed, with their weakened ships forced to scatter at the arrival of a Platine flotilla at Matarani. But the rebels would still score a sizable victory, as Colombian volunteers crossed the northern border and secured the interior beyond Jauja.

1833 would ultimately end with no major battles between republicans and loyalists, with the heaviest fighting that year taking place in Lima itself at the outset of the rebellion. But with the success of the war bond in the United Provinces, Platine and Colombian forces were now on a collision course. No formal declaration of war between Bogotá and La Plata would ever exist, but both countries would find themselves forced to escalate their involvement in the conflict as their soldiers clashed under the two different Peruvian flags. The Incan Crisis had only just begun.

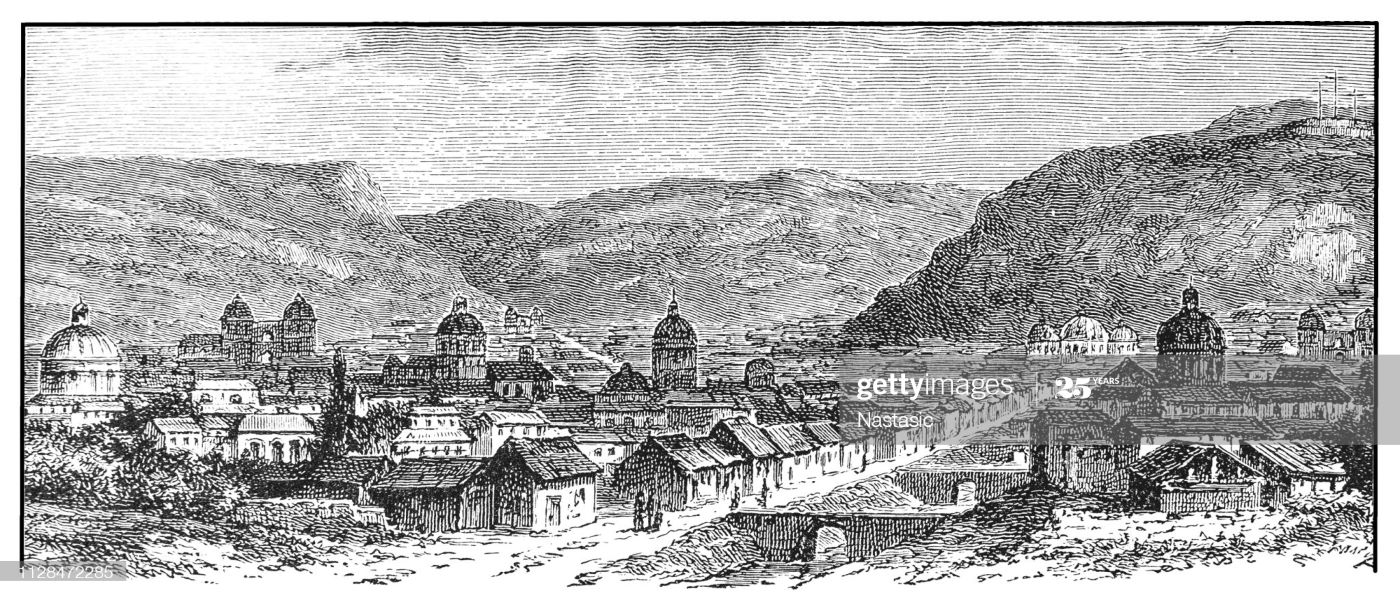

Cusco, before its explosive growth as the new permanent home of the restored Incan throne.

Author's note: I've decided to name this Chapter 13 instead of 16 since I think that the last 3 posts aren't really "narrative" chapters and should be differentiated as such.

Tupác Amarú II, leader of the largest revolt against Spanish rule prior to the Independence Wars, was officially legitimized by the constitution of the Empire of the Incas.

But even as the revolutionary armies triumphed on the field of battle and marched into the viceroyal capital as liberators, resistance to a restoration started to form in Lima. Its criollos had a considerably less romantic view of the idea, and although they had little recourse as the proposal rode the wave of revolutionary fervor to a jubilant majority in the country’s first constitutional assembly, its critics met, made plans and waited. The two leading candidates for the throne were 75 and 61 years old with no known male issue, and they had secured at least that the capital would remain in Lima as a concession to their complaints, so Lima’s criollos celebrated as Juan Bautista Túpac Amarú - brother of the one-time pretender and rebel leader Túpac Amarú II - took the regnal name Túpac Amarú III.

Lima’s criollos even mourned upon his death in 1827, and greeted the coronation of a distant relative of an ancient Incan emperor with dignity. But Dionisio Inca Yupanqui, who would assume the regnal name Túpac Inca Yupanqui II, wasn’t just younger than his predecessor when he took the throne: he had been heavily involved in the Cuzco revolutionary government during the war, and had remained active in local politics. Above all, he was an outspoken champion of native rights, whose equality was legally enshrined in the new constitution but who continued to face discrimination and exploitation, especially in Lima and the criollo-dominated cities of the coast.

When he proposed to move the capital away from Lima in the inaugural address to Congress in 1830, most in Lima paid it little attention: the Sapa Inka had little power in the new constitution, and although he was popular among representatives - having served alongside most of them during the reign of Túpac Amarú III - Lima’s leaders had no reason to believe it was a serious possibility.

Until Yupanqui II supplemented his lobbying of his former colleagues with a bolder move, which agitated Lima’s elites because they realized with horror that they had no legal recourse against it: although his powers had originally been conceived as purely symbolic, Yupanqui quickly realized that his person held a symbolic power of its own, and he began to spend the time between congressional sessions at his private residence in Cusco. Rather than paralyze the government over what they all believed was a formality, most government ministers simply worked around this by either moving to Cusco themselves or travelling when necessary.

Most Limans tolerated it as long as Congress and the ministries remained located in the capital, but Yupanqui upped the ante in 1833 when he had a minor Incan noble elevated to co-ruler to designate him as heir and decided to hold the coronation in Cusco. When the imperial entourage left Lima en route to Cusco, accompanied by sympathetic ministers and members of Congress, Lima erupted into open rebellion: its Cabildo was stormed by armed criollos, and they’d seize control of the city after a bloody day of street battles with the native regiments of the garrison. The ferocious fighting ended with hundreds of native civilians killed in the crossfire, as the criollos marched through their quarters in pursuit of fleeing loyalists.

Túpac Inca Yupanqui II proved to be a consummate and skilled politician even after his coronation as Sapa Inca, sparking the ire of Lima's criollo elite.

The rebellion got off to a strong start, taking control of Lima and receiving reports of sympathetic rebellions in other coastal cities, but it stalled soon after when the rebels failed to sway any of the military leaders outside of the cities they controlled: the army had been created by José de San Martín while he commanded the Army of the Andes, and San Martín - sympathetic with the idea of an Incan restoration and still a popular figure in Perú - had staffed it with like minded officers in the highest ranks. The most prominent criollo generals like Luis José de Orbegoso broke with Lima, while José de la Riva-Agüero proclaimed neutrality, garrisoning his regiment in Jauja and frustrating their plan to proclaim one of them as provisional president of their fledgling republic.

The rebels would ultimately turn to another prominent Liman criollo, Pedro Pablo Bermúdez Ascarza, electing the commander of the Lima garrison as Provisional President of the Republic of Perú in recognition of his role in securing the support of the garrison’s criollo units. They had to move quickly, as Yupanqui II had made it to Cusco and was already in the process of gathering troops in the city to launch a counter-attack on Lima. Their capture of the Lima garrison’s stores gave them an edge in terms of artillery, but their troops were primarily composed of criollo militias with only a handful of professional regiments joining the rebellion openly.

It might have been a brief civil war, if not for an unexpected visit from the Colombian ambassador: Bolivar’s shadow still loomed large in Colombia, and he had instilled in the young nation both a fierce republicanism and an animosity towards San Martín and the Incan monarchy he had helped restore on its border. They also feared the prospect of a Platine-dominated coalition in South America, isolating Colombia from its revolutionary brethren. Desperate for support, the Liman rebels acquiesced to the ambassador’s conditions, and soon a secret treaty was struck between the republican government to secure Colombian “volunteers” for their cause.

Most importantly for the rebels, Colombia would secure the Peruvian navy for the republicans by paying off the foreign captains. This gave the Limans the ships they needed to ferry the 2,000 Colombian regulars Bogotá was willing to send, although they’d have to strip several of the ships of cannons to replace the artillery that had been spiked by fleeing loyalists. But this dangerous escalation of the conflict, with news of the treaty reaching Cusco only a week later, forced Yupanqui II to seek foreign support himself: appealing to his prior support for the cause of the Incan monarchy and his role as liberator of Perú, Yupanqui pleaded with San Martín to send aid to the Cuscan army and help him subdue the republican revolt while it was still in its infancy.

He found a receptive government in San Martín and Monteagudo, but both faced an uphill battle to convince the General Assembly to support the proposal. The rebranded Catholic Party flatly rejected the idea, while the Federalists balked at the idea of sending Platine soldiers to fight a foreign government’s civil war. 3 delegates short of a majority, Monteagudo could not convince the Assembly to approve funds for any expedition.

But sympathy for the Incan monarchy was incredibly strong in Collao, and Monteagudo would not desist: appealing as he had to win his election to Collaoan Federalists, the party’s leadership eventually agreed to a compromise. As a workaround to the Assembly’s hesitance to allocate funds to the cause, Monteagudo proposed to finance it with a special war bond instead. Heavily advertised in the Liberal press, the war bond would prove to be an unexpected hit, with Collao’s remaining Incan nobles - allowed to use their ancestral titles and properties even if stripped of their corresponding privileges - buying them in huge quantities.

For all the violence of the initial insurrection, the civil war sputtered to a stalemate quickly as both camps worked to secure outside help. Riva-Agüero had received orders from both Lima and Cuscco, but he still refused to pick a side, and his garrison stood in the way of both. Liman efforts to capture the ports of Arequipa were rebuffed, with their weakened ships forced to scatter at the arrival of a Platine flotilla at Matarani. But the rebels would still score a sizable victory, as Colombian volunteers crossed the northern border and secured the interior beyond Jauja.

1833 would ultimately end with no major battles between republicans and loyalists, with the heaviest fighting that year taking place in Lima itself at the outset of the rebellion. But with the success of the war bond in the United Provinces, Platine and Colombian forces were now on a collision course. No formal declaration of war between Bogotá and La Plata would ever exist, but both countries would find themselves forced to escalate their involvement in the conflict as their soldiers clashed under the two different Peruvian flags. The Incan Crisis had only just begun.

Cusco, before its explosive growth as the new permanent home of the restored Incan throne.

Attachments

17 - The Incan Crisis (Part 2)

Chapter 14 - The Incan Crisis (Part 2)

The Republic of Perú was proclaimed in Lima on March 1st, 1833

As Platine and Colombian forces congregated in Cusco and Lima, their respective local allies began to snipe at one another on the peripheries of the front line. Direct offensives weren’t possible until Riva-Agüero committed to one side or the other, as his garrison remained fortified at a key junction of the road from Lima to Cusco, but skirmishes broke out along the hills and highlands that surrounded it.

The fighting quickly turned brutal, with criollo and native civilians alike forced to flee the country side as roving bands of armed rebels and loyalists searched for enemy supporters along the farms and villages of the Peruvian interior. Refugees flocked to the cities, attempting to find refuge behind the urban garrisons, but the economic and social situation on both sides of the civil war deteriorated rapidly: agricultural production ground to a halt, and as 1834 progressed, both camps were increasingly dependent on food shipments from their foreign supporters to keep the ballooning populations of their respective capital cities fed.

Part of the brutality may have been due to the harsh climate much of the fighting took place in, but by 1834, centuries of resentment between the natives and the criollo leaders who had profited most from Spanish colonial rule exploded into the open after the unity of the Independence Wars was tested. Public executions became a grim feature of daily life during the civil war, as both governments struggled to rein in the violent excesses of the people suffering and doing the brunt of the fighting.

The Colombian and Platine press highlighted the brutality of the opposing side, and support for the war grew in both countries as the news worsened. Both nations were proud of their role liberating other countries from Spanish tyranny, and both governments portrayed their expeditionary armies as a continuation of that legacy. The war fervor would reach its peak when Platine and Colombian forces first faced off in what would be known as the Callao Incident: a Colombian ship flying the flag of the Peruvian Republican was intercepted by the Platine privateer Esmeralda flying the flag of the Incan Empire as it approached Lima, and the Esmeralda proceeded to open fire when it refused to surrender.

The ship, laden heavy with ammunition and 200 Colombian regulars, explodes violently, killing all on board. The Colombian government lodged a formal complaint through its ambassador in La Plata, with the Platine government’s response that its ship had acted legally in service of the Incan Empire provoking a flurry of anti-Platine propaganda in Colombia. Colombian privateers would strike back, with a daring expedition rounding Cape Horn and attacking a string of small naval stations along the Patagonian coast, even setting fire to the Platine waystation on the Malvinas. Flying the ensign of the republican rebels, it hurt Platine pride more than its power, but would also be followed by revanchist propaganda that sparked a second flurry of purchases of Incan War Bonds.

The Callao Incident irreversibly soured Platine-Colombian relations in 1834.

The United Provinces would proceed to blockade the Peruvian rebels, leading to an expanding Platine presence in Patagonia to defend against future attacks. Although loose enough that smugglers operated with relative impunity, it made further Colombian naval shipments to Lima more dangerous and forced them to switch to the slower overland routes instead. This also forced the Colombian forces in Perú to act, as it became more expensive to keep their expedition supplied.

Riva-Agüero’s garrison at Jauja became their target: informants in the garrison had leaked that tensions were high in the city as the garrison’s native and criollo units eyed each other warily, and fistfights between regiments were growing more common as its commander’s neutrality strained his forces’ patience and became more and more unsustainable. With rebel forces attacking the city from two directions, cohesion within the garrison broke down as hundreds of criollos defected and fired on their former comrades in arms as they manned the walls or sallied.

The attack cleared a major obstacle on the road to Cusco, and 1,800 Colombian soldiers marched alongside over 4,000 criollo soldiers and militias, storming Huancayo, Huancavelica and Ayacucho in quick succession. But as they approached Abancay, their attack grinded to a halt as Platine light cavalry struck their strained supply lines; then the loyalist army, 1,500 Platine infantry bolstering its remaining 3,000 professionals soldiers and another 3,000 native militias, sallied from the last city standing between the rebels and Cusco.

Although outnumbered, they outgun the Incan army, exacting an especially heavy toll on the native militias that get caught unaware by an artillery barrage. But the bloody carnage eats through the rebel army’s gunpowder, and by the afternoon of October 2nd, the rebel army is forced to withdraw as they run out of supplies to keep firing in the face of a Platine counter battery. The loyalists give chase, forcing the rebels to abandon their spent artillery, but loyalist losses are too heavy to pursue any further than Jauja, with over 2,000 native irregulars killed or wounded in the Battle of Abancay, in addition to 800 casualties between Platine and Incan regulars.

Rebel losses are also heavy: its militias are equally bloodied, with over 1,500 criollo volunteers dead in the battle and the subsequent retreat. Colombian fatalities are relatively high, with their bravery letting the army escape at the cost of 500 dead in a last stand in the burnt remains of Jauja. Worst of all is its loss of its artillery advantage, with its remaining cannons needed to defend Lima forcing the republicans to scrap offensive plans.

It was now the royalists’ turn to attack: striking first at Tarma then at La Oroya, royalist forces captured the main outposts on the road to Lima and began to prepare for an assault on Lima itself. In a preview of things to come in the next phase of the war, the assault coincided with a fierce naval battle off the coast of Callao, as Colombian privateers fought desperately to prevent the Platine ships from helping the land attack. Despite heavy losses at sea, the gambit would succeed, and the royalists are forced to withdraw from range of Lima’s guns after a lucky shot struck a powder depot on the Platine side and incapacitated its artillery.

Like the year before, the front line would grind to a halt, with the biggest obstacle to new offensives being both sides’ lack of cannon and capacity to quickly make good their losses. Colombia and the United Provinces can replace some of it, but domestic production in both countries can barely cover their own needs, let alone the needs of a peripheral proxy war. Fighting shifts instead to the high seas, with Colombian and Platine ships fighting in both the Atlantic and the Pacific under the competing Peruvian flags.

It was soon becoming clear to the governments in Bogotá and La Plata that the resources needed to properly prosecute their respective war efforts far outstripped the resources even their sincere support for the competing causes allowed them to commit. Attrition in the expeditionary forces far outsripped the attrition in the local armies, surpassed only by the attrition in the militias, and the cost of supplying both the armies and the aid to prevent famine in Cusco and Lima were ballooning out of control.

By late 1834, the Platine mission had chewed through the funds raised by the bonds far faster than originally planned, and the bulk purchases of foodstuff to send north sparked riots in Córdoba and Tucumán as food prices in the United Provinces spiked. Colombia for its part feared that it would be unable to collect on the astronomical debt the Liman government had accrued with Colombian banks as the Platine blockade and the ongoing war destroyed the rebel government’s income.

As intense skirmishing continued between local troops, Colombian and Platine representatives met in Chile to negotiate a mutually agreeable settlement. Representatives from Lima and Cusco join them a week later, but all parties understand that without outside help, neither side can win the war. But too much blood had been spilled by both sides, and royalists and republicans alike were intransigent in their demand that their head of state remain in power.

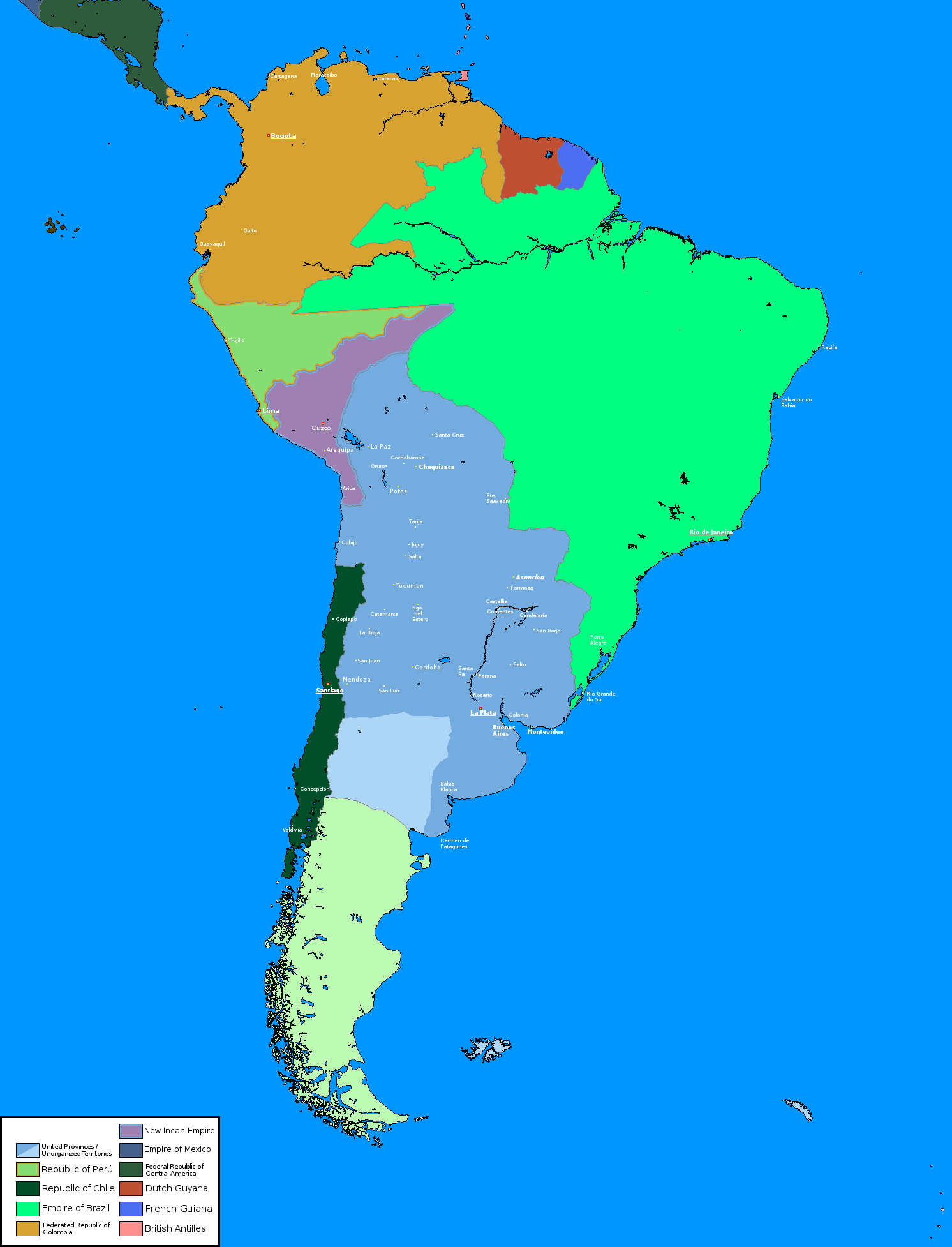

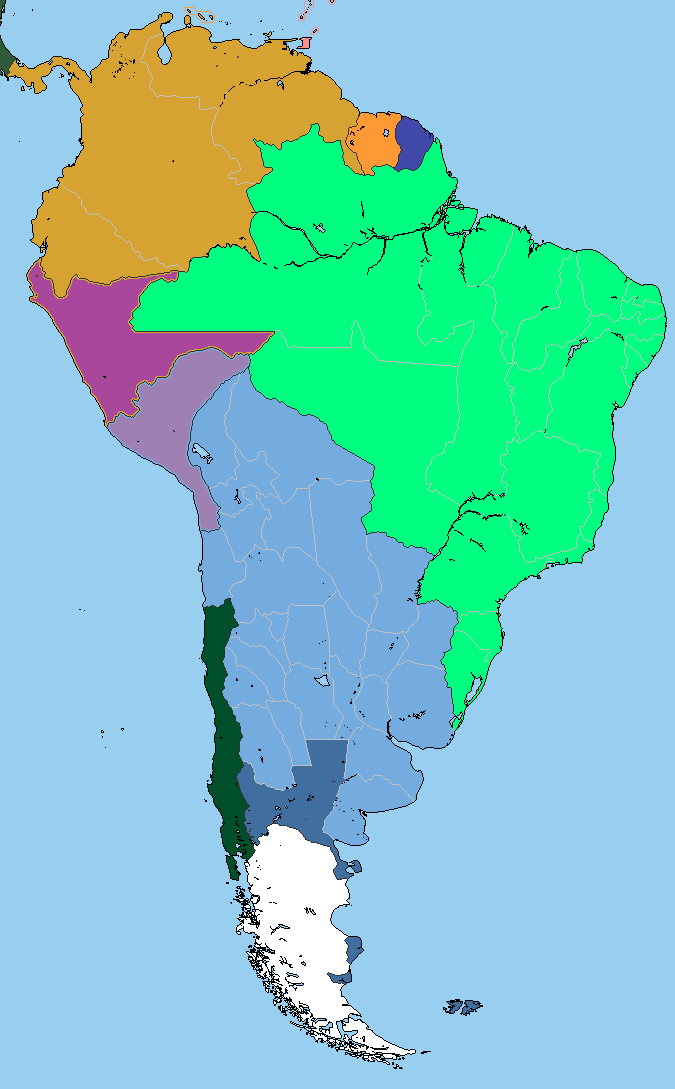

The frontline of the civil war would become the de facto border between the Republic of Perú and the Incan Empire of the Peruvians, which would change its name to the Musuq Tiwantinsuyu[1] after the Treaty of Santiago was signed between the governments of Lima and Cusco. The Incan Crisis marked the end of a united Perú, and showed both the reach and the limits of Platine and Colombian power in the region, essentially dividing Spanish-speaking South America at the new Peruvian border, with the two newly independent states drifting further into their sponsor’s arms: the border between Collao and the Incan Empire became as porous as it had been at the height of the Independence Wars, while Colombian goods and people travelled freely throughout the Republic.

The new flag adopted by the rump Incan state only further demonstrated that the ties binding Cusco to Platine Collao had grown even stronger during the Peruvian Civil War.--

[1] Unless I’ve horribly bundled the translation, this should translate roughly to “New Incan Empire” (or rather, “The New Four Regions”), latinized as Neo-Incan Empire.

The Republic of Perú was proclaimed in Lima on March 1st, 1833

The fighting quickly turned brutal, with criollo and native civilians alike forced to flee the country side as roving bands of armed rebels and loyalists searched for enemy supporters along the farms and villages of the Peruvian interior. Refugees flocked to the cities, attempting to find refuge behind the urban garrisons, but the economic and social situation on both sides of the civil war deteriorated rapidly: agricultural production ground to a halt, and as 1834 progressed, both camps were increasingly dependent on food shipments from their foreign supporters to keep the ballooning populations of their respective capital cities fed.

Part of the brutality may have been due to the harsh climate much of the fighting took place in, but by 1834, centuries of resentment between the natives and the criollo leaders who had profited most from Spanish colonial rule exploded into the open after the unity of the Independence Wars was tested. Public executions became a grim feature of daily life during the civil war, as both governments struggled to rein in the violent excesses of the people suffering and doing the brunt of the fighting.

The Colombian and Platine press highlighted the brutality of the opposing side, and support for the war grew in both countries as the news worsened. Both nations were proud of their role liberating other countries from Spanish tyranny, and both governments portrayed their expeditionary armies as a continuation of that legacy. The war fervor would reach its peak when Platine and Colombian forces first faced off in what would be known as the Callao Incident: a Colombian ship flying the flag of the Peruvian Republican was intercepted by the Platine privateer Esmeralda flying the flag of the Incan Empire as it approached Lima, and the Esmeralda proceeded to open fire when it refused to surrender.

The ship, laden heavy with ammunition and 200 Colombian regulars, explodes violently, killing all on board. The Colombian government lodged a formal complaint through its ambassador in La Plata, with the Platine government’s response that its ship had acted legally in service of the Incan Empire provoking a flurry of anti-Platine propaganda in Colombia. Colombian privateers would strike back, with a daring expedition rounding Cape Horn and attacking a string of small naval stations along the Patagonian coast, even setting fire to the Platine waystation on the Malvinas. Flying the ensign of the republican rebels, it hurt Platine pride more than its power, but would also be followed by revanchist propaganda that sparked a second flurry of purchases of Incan War Bonds.

The Callao Incident irreversibly soured Platine-Colombian relations in 1834.

The United Provinces would proceed to blockade the Peruvian rebels, leading to an expanding Platine presence in Patagonia to defend against future attacks. Although loose enough that smugglers operated with relative impunity, it made further Colombian naval shipments to Lima more dangerous and forced them to switch to the slower overland routes instead. This also forced the Colombian forces in Perú to act, as it became more expensive to keep their expedition supplied.

Riva-Agüero’s garrison at Jauja became their target: informants in the garrison had leaked that tensions were high in the city as the garrison’s native and criollo units eyed each other warily, and fistfights between regiments were growing more common as its commander’s neutrality strained his forces’ patience and became more and more unsustainable. With rebel forces attacking the city from two directions, cohesion within the garrison broke down as hundreds of criollos defected and fired on their former comrades in arms as they manned the walls or sallied.

The attack cleared a major obstacle on the road to Cusco, and 1,800 Colombian soldiers marched alongside over 4,000 criollo soldiers and militias, storming Huancayo, Huancavelica and Ayacucho in quick succession. But as they approached Abancay, their attack grinded to a halt as Platine light cavalry struck their strained supply lines; then the loyalist army, 1,500 Platine infantry bolstering its remaining 3,000 professionals soldiers and another 3,000 native militias, sallied from the last city standing between the rebels and Cusco.

Although outnumbered, they outgun the Incan army, exacting an especially heavy toll on the native militias that get caught unaware by an artillery barrage. But the bloody carnage eats through the rebel army’s gunpowder, and by the afternoon of October 2nd, the rebel army is forced to withdraw as they run out of supplies to keep firing in the face of a Platine counter battery. The loyalists give chase, forcing the rebels to abandon their spent artillery, but loyalist losses are too heavy to pursue any further than Jauja, with over 2,000 native irregulars killed or wounded in the Battle of Abancay, in addition to 800 casualties between Platine and Incan regulars.

Rebel losses are also heavy: its militias are equally bloodied, with over 1,500 criollo volunteers dead in the battle and the subsequent retreat. Colombian fatalities are relatively high, with their bravery letting the army escape at the cost of 500 dead in a last stand in the burnt remains of Jauja. Worst of all is its loss of its artillery advantage, with its remaining cannons needed to defend Lima forcing the republicans to scrap offensive plans.

It was now the royalists’ turn to attack: striking first at Tarma then at La Oroya, royalist forces captured the main outposts on the road to Lima and began to prepare for an assault on Lima itself. In a preview of things to come in the next phase of the war, the assault coincided with a fierce naval battle off the coast of Callao, as Colombian privateers fought desperately to prevent the Platine ships from helping the land attack. Despite heavy losses at sea, the gambit would succeed, and the royalists are forced to withdraw from range of Lima’s guns after a lucky shot struck a powder depot on the Platine side and incapacitated its artillery.

Like the year before, the front line would grind to a halt, with the biggest obstacle to new offensives being both sides’ lack of cannon and capacity to quickly make good their losses. Colombia and the United Provinces can replace some of it, but domestic production in both countries can barely cover their own needs, let alone the needs of a peripheral proxy war. Fighting shifts instead to the high seas, with Colombian and Platine ships fighting in both the Atlantic and the Pacific under the competing Peruvian flags.

It was soon becoming clear to the governments in Bogotá and La Plata that the resources needed to properly prosecute their respective war efforts far outstripped the resources even their sincere support for the competing causes allowed them to commit. Attrition in the expeditionary forces far outsripped the attrition in the local armies, surpassed only by the attrition in the militias, and the cost of supplying both the armies and the aid to prevent famine in Cusco and Lima were ballooning out of control.

By late 1834, the Platine mission had chewed through the funds raised by the bonds far faster than originally planned, and the bulk purchases of foodstuff to send north sparked riots in Córdoba and Tucumán as food prices in the United Provinces spiked. Colombia for its part feared that it would be unable to collect on the astronomical debt the Liman government had accrued with Colombian banks as the Platine blockade and the ongoing war destroyed the rebel government’s income.

As intense skirmishing continued between local troops, Colombian and Platine representatives met in Chile to negotiate a mutually agreeable settlement. Representatives from Lima and Cusco join them a week later, but all parties understand that without outside help, neither side can win the war. But too much blood had been spilled by both sides, and royalists and republicans alike were intransigent in their demand that their head of state remain in power.

The frontline of the civil war would become the de facto border between the Republic of Perú and the Incan Empire of the Peruvians, which would change its name to the Musuq Tiwantinsuyu[1] after the Treaty of Santiago was signed between the governments of Lima and Cusco. The Incan Crisis marked the end of a united Perú, and showed both the reach and the limits of Platine and Colombian power in the region, essentially dividing Spanish-speaking South America at the new Peruvian border, with the two newly independent states drifting further into their sponsor’s arms: the border between Collao and the Incan Empire became as porous as it had been at the height of the Independence Wars, while Colombian goods and people travelled freely throughout the Republic.

The new flag adopted by the rump Incan state only further demonstrated that the ties binding Cusco to Platine Collao had grown even stronger during the Peruvian Civil War.

[1] Unless I’ve horribly bundled the translation, this should translate roughly to “New Incan Empire” (or rather, “The New Four Regions”), latinized as Neo-Incan Empire.

1835 Map

I've decided to split off the map to its own post, because I think it warrants discussion; the borders roughly coincide with the borders of North Perú and South Perú, but I'm not sure this split makes sense. I've prepared two different versions of the map, and was hoping to get some feedback on which version seemed best.

I can only take credit for the second one, the first is the OTL flag of the Republic of Perú at the time, and I agree that it's quite lovely!Love those flags :3

Ah, a good all proxy war for the sake of gaining a puppet state. Truly we are entering the big leagues!

Now, personally I find that this entire war was kinda pointless (which IMO is a pretty nice change from "every war is a super epic do or die affair!" that a lot of stories get into) as it was nothing but two of South America's bigger states trying to impose their will on a weakened country and take them as puppets. All of which makes me wonder how history will see this war? I mean, at the end of the day no matter the rhetoric you can easily see how both sides did this mostly out of self interest.

All in all this may come bite the UP back in the ass in a few years. Expenditure of treasure and lives on foreign adventurism for no easily understandable gain is a risky proposition, the same for Colombia.

Now, personally I find that this entire war was kinda pointless (which IMO is a pretty nice change from "every war is a super epic do or die affair!" that a lot of stories get into) as it was nothing but two of South America's bigger states trying to impose their will on a weakened country and take them as puppets. All of which makes me wonder how history will see this war? I mean, at the end of the day no matter the rhetoric you can easily see how both sides did this mostly out of self interest.

All in all this may come bite the UP back in the ass in a few years. Expenditure of treasure and lives on foreign adventurism for no easily understandable gain is a risky proposition, the same for Colombia.

Me seeing Inca posting

More seriously, another fine update to this very fine TL. One wonders where Brazil will fall on this Cold War...

More seriously, another fine update to this very fine TL. One wonders where Brazil will fall on this Cold War...

Threadmarks

View all 54 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Platine Naval Ensign Army of the United Provinces San Martin Conmemorative Bill 25 - Teetering on the Brink - The Web of Alliances in the stands of the 1910 Centennial Parade 26 - The United Provinces and the Great War 27 - The 1919 General Strike Left Radical Party (PRI) Infobox 28 - The Raging 20s and New Ingredients in the Cauldron

Share: