Hold on I just realised something, Vinland? How the hell is it still known and around. Shouldn’t there be more European colonisation as a result?How does a pious Latin Catholic become a traitorous Orthodox Serbian?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A New Alexiad: Tarkhaneiotes Triumphant

- Thread starter Eparkhos

- Start date

Eparkhos

Banned

Hold on I just realised something, Vinland? How the hell is it still known and around. Shouldn’t there be more European colonisation as a result?

At this point Vinland was just a trading outpost and most commerce was in the local wood. Apart from a few outlaws, no one wanted to live there because life in Norway/Iceland/Greenland was either better or you had better chances of getting rich quick.

Got you. How come the year of a dozen emperors had so many, I mean it was crazy.At this point Vinland was just a trading outpost and most commerce was in the local wood. Apart from a few outlaws, no one wanted to live there because life in Norway/Iceland/Greenland was either better or you had better chances of getting rich quick.

Eparkhos

Banned

Got you. How come the year of a dozen emperors had so many, I mean it was crazy.

Well, Alexios VI was one, so that puts it down to seven

Ioannes VI was essentially a non-issue, so that's six

Ioannes V and Theodore III were both children, so that's four

That leaves us with Alexios VII, Konstantinos XII, Alexios VIII and Nikephoros IV

Konstantinos XII was the most ambitious of the Palaiologi, and as such would have inevitably popped up in any moment of weakness. It's honestly better for the Tarkhaneiotoi and the Empire that Konstantinos went for the throne in 1301 rather than in 1306.

Alexios VIII was just an ambitious man with the right resources to make a power grab in a period of instability

Alexios VII and Nikephoros IV were both ambitious man who used their connections to Alexios VI to attempt to claim the throne.

Jesus Christ, when the main emperor is MIA the empire goes to hell. Roman succession laws need to be laid down sooner lest a repeat and a far less positive ending occur,Well, Alexios VI was one, so that puts it down to seven

Ioannes VI was essentially a non-issue, so that's six

Ioannes V and Theodore III were both children, so that's four

That leaves us with Alexios VII, Konstantinos XII, Alexios VIII and Nikephoros IV

Konstantinos XII was the most ambitious of the Palaiologi, and as such would have inevitably popped up in any moment of weakness. It's honestly better for the Tarkhaneiotoi and the Empire that Konstantinos went for the throne in 1301 rather than in 1306.

Alexios VIII was just an ambitious man with the right resources to make a power grab in a period of instability

Alexios VII and Nikephoros IV were both ambitious man who used their connections to Alexios VI to attempt to claim the throne.

Eparkhos

Banned

1314:

Spring:

Alexios begins to prepare for the end of the truce with Rum. The Sultanate is coming out of a period of chaos after Mesut IV defeated a coalition of ghazis lead by Orhan Ertugrulolgu at Sivas in 1311.

Alexios divides the Turkish frontier into three commands:

§ His own, based at Dorylaion and with a strength of 8,000 foot and 3,000 hors

§ Theodoros, based at Sorogania with a strength of 7,000 foot and 2,000 horse

§ Sabbas, based at Philadelphia with a strength of 4,000 horse

Summer:

On the day after the peace expires (30 June) all three forces cross the frontier and march on their targets for the year. Alexios’ is Ankara, Theodores’s Sivas and Sabbas’ Konya. Sabbas’ objective is effectively a suicide mission.

Alexios’ advance goes unchallenged until he reaches the walls of Ankara. The city was the great trade center of inland Anatolia and a semi-independent city-state, and as such had the greatest defenses between Yumen and Konstantinopolis. The emperor arrives outside the city’s walls on 18 July only to be met by bristling defenses manned by 15,000 soldiers. He orders the construction of a defensive palisade behind his lines and settles in for a siege.

Theodore’s campaign is more difficult. As he marches through the rough country between Sorogania and Sivas his army is hit regularly by Turkish raids, slowing his advance. On 21 July he brings a group of 3,000 Turkish cavalry under Yahşi Karman to battle at Pashipinari. The horse archers are pinned with a cliff to their right and the Shirhan River to their left and back. Theodore orders his cavalry to charge. Across the river.

Holy bleep, kid, are you really that stupid?

The charge collapses as they come under withering fire and fall back, causing the Roman ranks to temporarily break as the horsemen attempt to push through to the rear. Karman seizes the opportunity and launches a full blown Atamanesque charge at the weak point in the lines. The Turks break through and route the Roman flank. In the chaos the camp is burned and with it most of the food stores.

Although the Turks lost 1,000 men to their own 500, without food the soldiers refuse to continue and the army dissolves. Over 3,000 are killed on the journey back to Trapezous, effectively ending action on the Pontic Front in 1314. Theodore and 20 loyalists turn west and ride for Ankara.

At this point you’re probably wondering how Mesut III is responding. He was in his capital at Konya and had only about 15,000 men available to him, all horse archers. He knew that Ankara would be able to hold out against either siege or assault. He dispatched Yahşi Karman and 3,000 cavalry north to attack Theodore and left 2,000 men behind to garrison Konya before marching against Philadelphia with 10,000 horse.

Sabbas’ strategy had been far more cautious than that of his brother or father. He left half of his force at Philadelphia and split the other half in half again, putting one column under the command of his friend Kyrillos Abrenetzis. (FIGHT ME) Both columns advanced into the hinterland through different passes. The benefits of this strategy were twofold: It kept the fields and pastures that they campaigned through fertile and meant that they would not starve if they retreated and it would not make the locals overly hostile or likely to put up resistance. Sabbas made a point of purchasing food from the local elders rather than simply requisitioning it. This was a welcome change for the often Romano-Turkish peasants of the border region and several ambushes were revealed as a result.

On 29 July Sabbas and his column were camped in a valley north of Chivril when they were woken by the sound of hooves. Mesut III and his entire army had fallen upon them in a night attack. In the frantic battle the Turkish Roman and the Turkish Turkish cavalry the Turkish cavalry began attacking each other, allowing Sabbas and about three hundred men to flee to Abrenetzis’ position fifteen minutes to the south. The combined force flees south-west towards the Lakes and the rocky, uneven ground that will slow down the pursuing Turks. On 14 August a rider arrives outside of Ankara begging Alexios for help. The emperor replies simply, “Tell my son to win his spurs.”

Sabbas and Abrenetzis continue their madcap run for safety. At some point they decide to turn and run for their coast. Over the course of August the column makes its way south towards the Bay of Attaleia. On 7 September the Romans take the city by surprise in a night attack. The city had been severely damaged during the Gazi War and had no garrison to speak of. When dawn comes Sabbas essentially declares “Nobody do anything stupid and we’ll be gone in a week.”

A ship is sent to Kypros and requests either an evacuation fleet or enough men to hold the city. The response comes on 22 September in the form of sixteen ships carrying 2,000 men. Attaleia is part of the empire for the first time since 1206.

That effectively ends the year.

Total score:

Cities taken: 1

Armies routed: 2

Causes of future civil strife: 2

Spring:

Alexios begins to prepare for the end of the truce with Rum. The Sultanate is coming out of a period of chaos after Mesut IV defeated a coalition of ghazis lead by Orhan Ertugrulolgu at Sivas in 1311.

Alexios divides the Turkish frontier into three commands:

§ His own, based at Dorylaion and with a strength of 8,000 foot and 3,000 hors

§ Theodoros, based at Sorogania with a strength of 7,000 foot and 2,000 horse

§ Sabbas, based at Philadelphia with a strength of 4,000 horse

Summer:

On the day after the peace expires (30 June) all three forces cross the frontier and march on their targets for the year. Alexios’ is Ankara, Theodores’s Sivas and Sabbas’ Konya. Sabbas’ objective is effectively a suicide mission.

Alexios’ advance goes unchallenged until he reaches the walls of Ankara. The city was the great trade center of inland Anatolia and a semi-independent city-state, and as such had the greatest defenses between Yumen and Konstantinopolis. The emperor arrives outside the city’s walls on 18 July only to be met by bristling defenses manned by 15,000 soldiers. He orders the construction of a defensive palisade behind his lines and settles in for a siege.

Theodore’s campaign is more difficult. As he marches through the rough country between Sorogania and Sivas his army is hit regularly by Turkish raids, slowing his advance. On 21 July he brings a group of 3,000 Turkish cavalry under Yahşi Karman to battle at Pashipinari. The horse archers are pinned with a cliff to their right and the Shirhan River to their left and back. Theodore orders his cavalry to charge. Across the river.

Holy bleep, kid, are you really that stupid?

The charge collapses as they come under withering fire and fall back, causing the Roman ranks to temporarily break as the horsemen attempt to push through to the rear. Karman seizes the opportunity and launches a full blown Atamanesque charge at the weak point in the lines. The Turks break through and route the Roman flank. In the chaos the camp is burned and with it most of the food stores.

Although the Turks lost 1,000 men to their own 500, without food the soldiers refuse to continue and the army dissolves. Over 3,000 are killed on the journey back to Trapezous, effectively ending action on the Pontic Front in 1314. Theodore and 20 loyalists turn west and ride for Ankara.

At this point you’re probably wondering how Mesut III is responding. He was in his capital at Konya and had only about 15,000 men available to him, all horse archers. He knew that Ankara would be able to hold out against either siege or assault. He dispatched Yahşi Karman and 3,000 cavalry north to attack Theodore and left 2,000 men behind to garrison Konya before marching against Philadelphia with 10,000 horse.

Sabbas’ strategy had been far more cautious than that of his brother or father. He left half of his force at Philadelphia and split the other half in half again, putting one column under the command of his friend Kyrillos Abrenetzis. (FIGHT ME) Both columns advanced into the hinterland through different passes. The benefits of this strategy were twofold: It kept the fields and pastures that they campaigned through fertile and meant that they would not starve if they retreated and it would not make the locals overly hostile or likely to put up resistance. Sabbas made a point of purchasing food from the local elders rather than simply requisitioning it. This was a welcome change for the often Romano-Turkish peasants of the border region and several ambushes were revealed as a result.

On 29 July Sabbas and his column were camped in a valley north of Chivril when they were woken by the sound of hooves. Mesut III and his entire army had fallen upon them in a night attack. In the frantic battle the Turkish Roman and the Turkish Turkish cavalry the Turkish cavalry began attacking each other, allowing Sabbas and about three hundred men to flee to Abrenetzis’ position fifteen minutes to the south. The combined force flees south-west towards the Lakes and the rocky, uneven ground that will slow down the pursuing Turks. On 14 August a rider arrives outside of Ankara begging Alexios for help. The emperor replies simply, “Tell my son to win his spurs.”

Sabbas and Abrenetzis continue their madcap run for safety. At some point they decide to turn and run for their coast. Over the course of August the column makes its way south towards the Bay of Attaleia. On 7 September the Romans take the city by surprise in a night attack. The city had been severely damaged during the Gazi War and had no garrison to speak of. When dawn comes Sabbas essentially declares “Nobody do anything stupid and we’ll be gone in a week.”

A ship is sent to Kypros and requests either an evacuation fleet or enough men to hold the city. The response comes on 22 September in the form of sixteen ships carrying 2,000 men. Attaleia is part of the empire for the first time since 1206.

That effectively ends the year.

Total score:

Cities taken: 1

Armies routed: 2

Causes of future civil strife: 2

Last edited:

Advisory #4

Eparkhos

Banned

Sorry, 1315 has run long and as such I have not been able to complete it. It will be up tomorrow.

Revival Anouncement

Eparkhos

Banned

A-hem.

Alright, so the laptop that I wrote most of A New Alexiad on broke badly last week. While I was trying to recover at least part of its contents, I stumbled upon an old draft of 1310 from July. This prompted me to start thinking about ANA, and within a few days I had come up with a basic draft of the period after 1310.

As such, A New Alexiad is coming back from hiatus. Updates will not be daily, but there will be several per week.

Alright, so the laptop that I wrote most of A New Alexiad on broke badly last week. While I was trying to recover at least part of its contents, I stumbled upon an old draft of 1310 from July. This prompted me to start thinking about ANA, and within a few days I had come up with a basic draft of the period after 1310.

As such, A New Alexiad is coming back from hiatus. Updates will not be daily, but there will be several per week.

1310 (Cannonical)

Eparkhos

Banned

1310

Winter

Gazi Çelebi, unwilling to risk destruction at the hands of rough winter currents in the Aegean, anchors on the eastern side of the Hekatonesoi Archipelago, south-west along the coast from Adrymittion in mid-January. The Nikomedian fleet loses track of him and turns for home, leaving a 6-squadron fleet under the command of the Italian-trained Roman mariner Demetrios Akakios at Tenedos.

On 21 January, a fisherman from Kydonies sails directly into Çelebi’s fleet. Its captain manages to wheel around and streaks for land, dodging the pursuing pirates in the dense island cluster and safely reaching the port. The city’s garrison commander sends a rider to Adrymittion, whose commander then sends two further on; one to Nikomedia and one to Kalliopolis, both to succor aid. Akakios somehow catches wind of this and sails after Çelebi, eager for glory and irreverent of the climactic dangers..

Çelebi had believed that he still had time to leave before a Roman fleet arrived, and as such had remained in place while waiting for the weather to clear. As such, he and his men were taken by surprise when Akakios and his flotilla burst out of the Hekatonesoi Strait on the south-west face of the archipelago, a fierce easterly at their backs on 27 January. The Roman ships are able to take the pirates while they are at anchor, setting several unmanned ships alight and stranding their crews on the island. Çelebi is able to board his ship, turning north with 4 of his 17 ships and circling around the island to run south-west in Lesbos’ shadow. Akakios is unable to track him down, and as so turns back to Adrymittion on the 29th.

Simeon II shows up outside the gates of Vratsa, alone and unarmed, on 7 February.. He shouts up to the guards that, “If you wish to be the hounds of the Roman, then slay me. May he who has the heart slay the Tsar!”. Most of the soldiers, dismissing him as an imposter, ignore him; However, a group of Bulgarian auxiliaries had been left unattended in one of the gatehouses and they admitted him. Vratsa was a major training center, and there were upwards of 1,500 armed Bulgarians within its walls. Simeon rallies them against the Romans and they massacre the few dozen Romans within the city before leading 1,200 south towards Traiditza. They are joined by several hundred (~600) militiamen armed with farming implements and tools.

They descend into the plains surrounding Traiditza on the 9th, appearing beneath the walls at dawn on the 10th. The city was held only by two hundred Armanj auxiliaries, many of whom when confronted by how screwed they are quickly defect to Simeon; the few that don’t are killed. The new cavalry are dispatched south-east with light infantry accompaniment to occupy the abandoned defenses at Stipon.

Spring

Iancu raids across the Hungarian frontier, burning several towns and laying siege to the county capital of Deva in the third week of March. He retreats before the local counts can respond, but has made a fatal mistake in assaulting the lands of Vaclav the Iron-Willed.

Simeon’s makeshift army continues to advance east along the northern slope of the Haemus, relieving the garrison of Anevsko on the 23rd, and pushing on to lay siege to the lightly-defended fortress of Hisarya on the 30th.

News of the Tsar’s return reach Konstantinoupoli on 2 April. The Emperor is irate. Rhomaion had suffered under Bulgarian raids for the last thirty year, and he was determined that he would end it. He orders Nikephoros to gather what few surviving retainers the Asens have and to prepare them for war. He then sends a rider to the Thrakesion; He will end this war and will do so with the best men he has, his veterans from before his rise to the throne. He also raises the men of the Thrakian Khersonese, 3,000 Nikephorian soldiers.

Simeon spends April criss-crossing western Bulgaria, calling the peasants to arms and trapping the Roman garrisons within the few fortresses scattered across the plain. He manages to mass an army of 9,000 foot and 1,500 cavalry, mostly militia. In Eastern Bulgaria, the Cuman nobleman Georgi Terter raises a pro-Asenist army of 4,000 foot and marches on Tarnovo in preparation for the Emperor’s coming. Terter reaches the city on 27 April, but decides to continue on to confront Simeon. However, upon learning of the size of the rebel army he changes his mind and falls back to the capital.

The mounted infantry[1] of the Thrakesion, 4,000 strong, arrive outside of Konstantinoupoli on 6 May. Alexios combines them with the Thrakian Khersonesians and marches north, crossing the Haemusus in late May and arriving Lardea on 30 May.

Summer

The Imperial army, now 11,000 strong, advances west along the mountains in pursuit of Simeon. They relieve the garrisons of several of the besieged fortresses between the Yantra and Iskar but do not re-occupy them as Alexios is unwilling to reduce his slim numerical advantage. The fortresses are instead demolished, which slows their progress down. They finally arrive on the Iskar on 18 July.

Simeon has not spent June idly, however, and has trained his militia into an effective fighting force. He positions his infantry, the heart of his force, in a small valley thirty miles north of Traiditza, called Skravina, while sending the cavalry north, across the mountains into the Danube plain. His plan was to use the cavalry to bait the Romans into the pass and then draw them directly into the rebel lines. By the time the Armanj descend onto the plain, it is 24 July.

Alexios’ scouts misreport this as the entirety of Simeon’s army crossing the mountains to meet the Romans. The emperor detaches 2,000 mounted infantry to circle around through a secondary pass to sweep in and trap the Bulgarians from behind while he advances towards the pass to cork it. The cavalry fall back as planned, but upon the arrival of the mounted infantry in their rear they panic and barrel through the Romans before they can dismount. The mounted infantry

Simeon is informed of the Roman advance, but as the Bulgarian cavalry had collapsed back into the camp the Tsar is unable to form his infantry into proper formation. He orders the auxiliaries to advance to the pass and fight a rearguard action against the Romans. The Tsar accompanies them, leaving the rest of the Bulgarian army to withdraw without a unified leadership.

The two sides meet in the pass. Fighting is fierce and both sides take heavy losses, but the auxiliaries are able to hold the Romans off until sunset, when both sides retire. There is an apocryphal story of Alexios and Simeon fighting a duel on the field of battle, but the outcome is so similar to the eventual end of the war that it is usually discounted as a legend.

Simeon rides for most of the night, reaching Traiditza before dawn. Knowing that the emperor is not far behind, he sleeps for an hour before taking command of the ~4,000 Bulgarians that had made it to the city and marching north-west on the 25th.

Alexios does indeed pursue, detaching the mounted infantry from the rest of the Roman army and riding south after Simeon. The Khersonesians are left behind to besiege the city and the Asenites are ordered north-west to continue the push along the plain to the Serbian border.

The two monarchs make northwest towards Serbia, Simeon just a few hours ahead of the Romans. In early August, Simeon crosses over the Serbian border, adding another layer to the pursuit. Serbian militia join the hunt, attempting to slow down the Bulgarians.

Thus passes August.

Autumn

The pursuit continues over the rest of the fall, the Romans being unable to take the Bulgarians and the Bulgarians unwilling to risk battle. The flight wares on the Bulgarians, and in mid-November Simeon dismisses his men and rides alone across the border into Vlachia.

Alexios, partially satisfied by Simeon’s flight, retires back to Konstantinoupli, arriving outside the city on 29 November. The Thrakesians escort Sofiya Asen across the mountains to Tarnovo, where she is coronated again on 11 December.

Winter

Gazi Çelebi, unwilling to risk destruction at the hands of rough winter currents in the Aegean, anchors on the eastern side of the Hekatonesoi Archipelago, south-west along the coast from Adrymittion in mid-January. The Nikomedian fleet loses track of him and turns for home, leaving a 6-squadron fleet under the command of the Italian-trained Roman mariner Demetrios Akakios at Tenedos.

On 21 January, a fisherman from Kydonies sails directly into Çelebi’s fleet. Its captain manages to wheel around and streaks for land, dodging the pursuing pirates in the dense island cluster and safely reaching the port. The city’s garrison commander sends a rider to Adrymittion, whose commander then sends two further on; one to Nikomedia and one to Kalliopolis, both to succor aid. Akakios somehow catches wind of this and sails after Çelebi, eager for glory and irreverent of the climactic dangers..

Çelebi had believed that he still had time to leave before a Roman fleet arrived, and as such had remained in place while waiting for the weather to clear. As such, he and his men were taken by surprise when Akakios and his flotilla burst out of the Hekatonesoi Strait on the south-west face of the archipelago, a fierce easterly at their backs on 27 January. The Roman ships are able to take the pirates while they are at anchor, setting several unmanned ships alight and stranding their crews on the island. Çelebi is able to board his ship, turning north with 4 of his 17 ships and circling around the island to run south-west in Lesbos’ shadow. Akakios is unable to track him down, and as so turns back to Adrymittion on the 29th.

Simeon II shows up outside the gates of Vratsa, alone and unarmed, on 7 February.. He shouts up to the guards that, “If you wish to be the hounds of the Roman, then slay me. May he who has the heart slay the Tsar!”. Most of the soldiers, dismissing him as an imposter, ignore him; However, a group of Bulgarian auxiliaries had been left unattended in one of the gatehouses and they admitted him. Vratsa was a major training center, and there were upwards of 1,500 armed Bulgarians within its walls. Simeon rallies them against the Romans and they massacre the few dozen Romans within the city before leading 1,200 south towards Traiditza. They are joined by several hundred (~600) militiamen armed with farming implements and tools.

They descend into the plains surrounding Traiditza on the 9th, appearing beneath the walls at dawn on the 10th. The city was held only by two hundred Armanj auxiliaries, many of whom when confronted by how screwed they are quickly defect to Simeon; the few that don’t are killed. The new cavalry are dispatched south-east with light infantry accompaniment to occupy the abandoned defenses at Stipon.

Spring

Iancu raids across the Hungarian frontier, burning several towns and laying siege to the county capital of Deva in the third week of March. He retreats before the local counts can respond, but has made a fatal mistake in assaulting the lands of Vaclav the Iron-Willed.

Simeon’s makeshift army continues to advance east along the northern slope of the Haemus, relieving the garrison of Anevsko on the 23rd, and pushing on to lay siege to the lightly-defended fortress of Hisarya on the 30th.

News of the Tsar’s return reach Konstantinoupoli on 2 April. The Emperor is irate. Rhomaion had suffered under Bulgarian raids for the last thirty year, and he was determined that he would end it. He orders Nikephoros to gather what few surviving retainers the Asens have and to prepare them for war. He then sends a rider to the Thrakesion; He will end this war and will do so with the best men he has, his veterans from before his rise to the throne. He also raises the men of the Thrakian Khersonese, 3,000 Nikephorian soldiers.

Simeon spends April criss-crossing western Bulgaria, calling the peasants to arms and trapping the Roman garrisons within the few fortresses scattered across the plain. He manages to mass an army of 9,000 foot and 1,500 cavalry, mostly militia. In Eastern Bulgaria, the Cuman nobleman Georgi Terter raises a pro-Asenist army of 4,000 foot and marches on Tarnovo in preparation for the Emperor’s coming. Terter reaches the city on 27 April, but decides to continue on to confront Simeon. However, upon learning of the size of the rebel army he changes his mind and falls back to the capital.

The mounted infantry[1] of the Thrakesion, 4,000 strong, arrive outside of Konstantinoupoli on 6 May. Alexios combines them with the Thrakian Khersonesians and marches north, crossing the Haemusus in late May and arriving Lardea on 30 May.

Summer

The Imperial army, now 11,000 strong, advances west along the mountains in pursuit of Simeon. They relieve the garrisons of several of the besieged fortresses between the Yantra and Iskar but do not re-occupy them as Alexios is unwilling to reduce his slim numerical advantage. The fortresses are instead demolished, which slows their progress down. They finally arrive on the Iskar on 18 July.

Simeon has not spent June idly, however, and has trained his militia into an effective fighting force. He positions his infantry, the heart of his force, in a small valley thirty miles north of Traiditza, called Skravina, while sending the cavalry north, across the mountains into the Danube plain. His plan was to use the cavalry to bait the Romans into the pass and then draw them directly into the rebel lines. By the time the Armanj descend onto the plain, it is 24 July.

Alexios’ scouts misreport this as the entirety of Simeon’s army crossing the mountains to meet the Romans. The emperor detaches 2,000 mounted infantry to circle around through a secondary pass to sweep in and trap the Bulgarians from behind while he advances towards the pass to cork it. The cavalry fall back as planned, but upon the arrival of the mounted infantry in their rear they panic and barrel through the Romans before they can dismount. The mounted infantry

Simeon is informed of the Roman advance, but as the Bulgarian cavalry had collapsed back into the camp the Tsar is unable to form his infantry into proper formation. He orders the auxiliaries to advance to the pass and fight a rearguard action against the Romans. The Tsar accompanies them, leaving the rest of the Bulgarian army to withdraw without a unified leadership.

The two sides meet in the pass. Fighting is fierce and both sides take heavy losses, but the auxiliaries are able to hold the Romans off until sunset, when both sides retire. There is an apocryphal story of Alexios and Simeon fighting a duel on the field of battle, but the outcome is so similar to the eventual end of the war that it is usually discounted as a legend.

Simeon rides for most of the night, reaching Traiditza before dawn. Knowing that the emperor is not far behind, he sleeps for an hour before taking command of the ~4,000 Bulgarians that had made it to the city and marching north-west on the 25th.

Alexios does indeed pursue, detaching the mounted infantry from the rest of the Roman army and riding south after Simeon. The Khersonesians are left behind to besiege the city and the Asenites are ordered north-west to continue the push along the plain to the Serbian border.

The two monarchs make northwest towards Serbia, Simeon just a few hours ahead of the Romans. In early August, Simeon crosses over the Serbian border, adding another layer to the pursuit. Serbian militia join the hunt, attempting to slow down the Bulgarians.

Thus passes August.

Autumn

The pursuit continues over the rest of the fall, the Romans being unable to take the Bulgarians and the Bulgarians unwilling to risk battle. The flight wares on the Bulgarians, and in mid-November Simeon dismisses his men and rides alone across the border into Vlachia.

Alexios, partially satisfied by Simeon’s flight, retires back to Konstantinoupli, arriving outside the city on 29 November. The Thrakesians escort Sofiya Asen across the mountains to Tarnovo, where she is coronated again on 11 December.

Last edited:

1311 (Cannonical)

Eparkhos

Banned

1311

Winter

Simeon stumbles into the court of Vaclav the Iron-Willed in Esztergom on 22 February. He begs for sanctuary, hurriedly explaining to the Thrice-Crowned that sheltering him would benefit them both by giving Vaclav the ability to disrupt Bulgaria at will and by giving Simeon shelter from pursuers. Vaclav agrees and allows the dethroned Tsar to join his court.

Spring

Iancu crosses the Danube and begins raiding the Bulgarian frontier in the third week of March. Nikephoros and Terter both rush to drive the Vlachs off. Terter seeks to undermine the legitimacy of the Asens and seize power for himself, his campaign against Simeon the year previous being only an attempt to destroy a rival. However, the division of the Bulgarian army allows the Vlachs to escape back across the river on 3 April.

In the far east of the empire, a Lazic tribe called the Amytzantarioi go into revolt against the central government, hailing Manouel Megas Komnenos, the nephew of Ioannes II, as the Emperor of Trapezous on 14 April.. Manouel leads them down from the highlands to besiege the lightly-defended fortress of Rhizaion. The castle falls after a three-day siege, the small garrison fleeing by ship to Trapezous. The Amytzantarioi garrison it, then turn west and march on the former capital numbering 7,000.

The provincial governor, Konstantinos Meliteniotes, raises 3,500 regular infantry and marches to meet them. Meliteniotes reaches Sourmana on 21 April, digging in to limit the numerical advantage that the Amytzantarioi hold. The rebels take the coastal city of Ophious on 24 April, hiring several merchantmen to scout along the coast. The merchants instead sail to Sourmana, inform Meliteniotes of Megas Komnenos’ position and then continue on their way.

On the 29th, the Amytzantarioi reach the Roman lines. Manouel is unable to form them into a proper line, resulting in them charging pell-mell into the Roman trenches. They are predictably cut down with heavy losses, falling back into a camp two miles away. After nightfall, Meliteniotes surges forward and surrounds the camp before setting it alight. Among the dead is the would-be emperor.

Meliteniotes then rounds up the few surviving Megas Komnenoi and imprisons them in the dungeons of Trapezous. The only survivor is Anna Anakhtoulou, the young daughter of Alexios II, who was on pilgrimage to Jerusalem at the time.

Summer

Stefan Milutin and his daughter Jelena arrive in Konstantinoupoli on 21 May. However, the patriarch refuses to officiate a marriage between the Crown Prince and Jelena, citing the age of the former. Alexios attempts to force him to do it anyway, but for once the decision is in line with official Church doctrine and the other clergy of the city back Nikolaos up. Given as he had taken great expense to haul the dowry overland across Bulgaria and Thrake Milutin decides to leave his daughter, the dowry and two hundred and fifty retainers in the city while he takes ship back to Serbia. Alexios swears a sacred oath not to touch any of it until the ceremony, which is set for 4 October 1313. On 29 May, the Serbian king departs the capital via boat back to Budva. The Serbians are housed in the Botaneiatioi Palace, which was still in usable shape as the Imperial family had only moved to the Monomakhid Palace seven years previous.

On 3 June, Clement V gives a sermon in Avignon, calling for a crusade to “... reestablish the Christian states of Outremer…”. Philip IV of France and Jaime II both take the cross, so to speak, and begin preparing for an expedition. News of this arrives in Konstantinoupoli sometime in late June and Alexios begins ordering food and water stored in the cisterns underneath the city. Were the Crusaders to attack Rhomaion, they would be prepared.

In late July, a Turkish raiding party has the misfortune to raid into the Il-Khanate five miles from the location of Nikolya and 10,000 mounted archers, returning from a successful campaign to Jerusalem. Nikolya runs them down and massacres them, then begins planning an invasion of Rum.

On 17 August, Nikolaos Glabas issues an edict against the Patranites, starting the Great Persecution. Almost a thousand heretics are rounded up and hacked to death in Thessalonika. This forces the Patranites to go underground, starting their common practice of intense secrecy.

Autumn

On 3 September, a group of Basque Crusaders attempt to pass through the Iberian straits en route to the Balearics. The local Moors sail out to attack them, but in the course of the fight the Basques turn the tide and pursue their attackers back to their moorings at Jabal Tariq. The Crusaders launch a makeshift amphibious assault and storm the rock, capturing it. Their leader, Luken de Aguirre, declares himself Count of Gibraltar the next day.

A would-be assassin is captured by the Papioi while attempting to slip into the Imperial nursery on the night of 27 September. The man does not crack under several days of ‘intense interrogation’, leading to the belief that he was sent by one of the empire’s neighbors. No official action is taken, but Khagan Tügä of the Nogai Horde falls through his lattice on 13 October. He is succeeded by his brother Toraï.

The harvest in Southern Italy fails for the third year in a row, especially hard in the lands under the Crown of Aragon. This triggers an exodus from Salento, with roughly two-thirds of the rural population either crossing into Sicily or, primarily amongst the Gkreko-speaking minorities of Kalabria, to the Empire. Of the roughly 40,000 Kalabrian Gkrekos, upwards of 15,000 risk a winter passage of the Adriatic to escape the hunger. Less than half of them make it, but those who do are resettled on the Paphlagonian coast, where they begin to form the insular communities that would preserve their customs into the modern day.

Winter

Simeon stumbles into the court of Vaclav the Iron-Willed in Esztergom on 22 February. He begs for sanctuary, hurriedly explaining to the Thrice-Crowned that sheltering him would benefit them both by giving Vaclav the ability to disrupt Bulgaria at will and by giving Simeon shelter from pursuers. Vaclav agrees and allows the dethroned Tsar to join his court.

Spring

Iancu crosses the Danube and begins raiding the Bulgarian frontier in the third week of March. Nikephoros and Terter both rush to drive the Vlachs off. Terter seeks to undermine the legitimacy of the Asens and seize power for himself, his campaign against Simeon the year previous being only an attempt to destroy a rival. However, the division of the Bulgarian army allows the Vlachs to escape back across the river on 3 April.

In the far east of the empire, a Lazic tribe called the Amytzantarioi go into revolt against the central government, hailing Manouel Megas Komnenos, the nephew of Ioannes II, as the Emperor of Trapezous on 14 April.. Manouel leads them down from the highlands to besiege the lightly-defended fortress of Rhizaion. The castle falls after a three-day siege, the small garrison fleeing by ship to Trapezous. The Amytzantarioi garrison it, then turn west and march on the former capital numbering 7,000.

The provincial governor, Konstantinos Meliteniotes, raises 3,500 regular infantry and marches to meet them. Meliteniotes reaches Sourmana on 21 April, digging in to limit the numerical advantage that the Amytzantarioi hold. The rebels take the coastal city of Ophious on 24 April, hiring several merchantmen to scout along the coast. The merchants instead sail to Sourmana, inform Meliteniotes of Megas Komnenos’ position and then continue on their way.

On the 29th, the Amytzantarioi reach the Roman lines. Manouel is unable to form them into a proper line, resulting in them charging pell-mell into the Roman trenches. They are predictably cut down with heavy losses, falling back into a camp two miles away. After nightfall, Meliteniotes surges forward and surrounds the camp before setting it alight. Among the dead is the would-be emperor.

Meliteniotes then rounds up the few surviving Megas Komnenoi and imprisons them in the dungeons of Trapezous. The only survivor is Anna Anakhtoulou, the young daughter of Alexios II, who was on pilgrimage to Jerusalem at the time.

Summer

Stefan Milutin and his daughter Jelena arrive in Konstantinoupoli on 21 May. However, the patriarch refuses to officiate a marriage between the Crown Prince and Jelena, citing the age of the former. Alexios attempts to force him to do it anyway, but for once the decision is in line with official Church doctrine and the other clergy of the city back Nikolaos up. Given as he had taken great expense to haul the dowry overland across Bulgaria and Thrake Milutin decides to leave his daughter, the dowry and two hundred and fifty retainers in the city while he takes ship back to Serbia. Alexios swears a sacred oath not to touch any of it until the ceremony, which is set for 4 October 1313. On 29 May, the Serbian king departs the capital via boat back to Budva. The Serbians are housed in the Botaneiatioi Palace, which was still in usable shape as the Imperial family had only moved to the Monomakhid Palace seven years previous.

On 3 June, Clement V gives a sermon in Avignon, calling for a crusade to “... reestablish the Christian states of Outremer…”. Philip IV of France and Jaime II both take the cross, so to speak, and begin preparing for an expedition. News of this arrives in Konstantinoupoli sometime in late June and Alexios begins ordering food and water stored in the cisterns underneath the city. Were the Crusaders to attack Rhomaion, they would be prepared.

In late July, a Turkish raiding party has the misfortune to raid into the Il-Khanate five miles from the location of Nikolya and 10,000 mounted archers, returning from a successful campaign to Jerusalem. Nikolya runs them down and massacres them, then begins planning an invasion of Rum.

On 17 August, Nikolaos Glabas issues an edict against the Patranites, starting the Great Persecution. Almost a thousand heretics are rounded up and hacked to death in Thessalonika. This forces the Patranites to go underground, starting their common practice of intense secrecy.

Autumn

On 3 September, a group of Basque Crusaders attempt to pass through the Iberian straits en route to the Balearics. The local Moors sail out to attack them, but in the course of the fight the Basques turn the tide and pursue their attackers back to their moorings at Jabal Tariq. The Crusaders launch a makeshift amphibious assault and storm the rock, capturing it. Their leader, Luken de Aguirre, declares himself Count of Gibraltar the next day.

A would-be assassin is captured by the Papioi while attempting to slip into the Imperial nursery on the night of 27 September. The man does not crack under several days of ‘intense interrogation’, leading to the belief that he was sent by one of the empire’s neighbors. No official action is taken, but Khagan Tügä of the Nogai Horde falls through his lattice on 13 October. He is succeeded by his brother Toraï.

The harvest in Southern Italy fails for the third year in a row, especially hard in the lands under the Crown of Aragon. This triggers an exodus from Salento, with roughly two-thirds of the rural population either crossing into Sicily or, primarily amongst the Gkreko-speaking minorities of Kalabria, to the Empire. Of the roughly 40,000 Kalabrian Gkrekos, upwards of 15,000 risk a winter passage of the Adriatic to escape the hunger. Less than half of them make it, but those who do are resettled on the Paphlagonian coast, where they begin to form the insular communities that would preserve their customs into the modern day.

Last edited:

Eparkhos

Banned

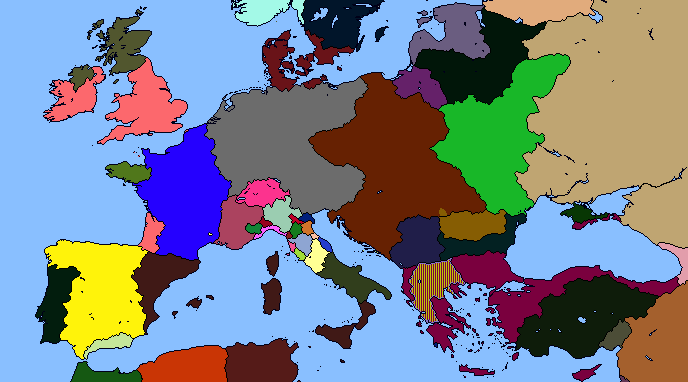

What is the striped territory in the Empire?

Those are the lands of Nikolaos Glabas, the 'Exarkh' of Thessalonika. He's been ruling as a nearly autonomous lord since 1307, when he made a bid for independence that the Emperor was too busy in Bulgaria to put down. They compromised, with Glabas being given the title of Exarkh and allowed a degree of autonomy while still paying tribute to the throne.

1312

Eparkhos

Banned

1312

Winter

A daughter is born to Sancia and Alexios, named Demetria. The girl is very ill on birth, but the Imperial doctors are able to stabilize her and she is able to pull through.

Spring

A peasant revolt begins in far-off Namen in mid-April, initially protesting the heavy taxes laid upon the march before devolving into a wandering mob with vague ideas of self-governance. They lay siege to Namen on the 26th of April, breaking down the gates on the 28th before storming into the city and killing almost everyone inside. A few dozen guards, mostly old retainers of Caterine, fall back with the few surviving de Courtenays to the fortified Abbey of Gembloux, on the border with the Duchy of Brabant. Calls for aid to the neighboring Counties of Loon and Hainaut go unanswered, but on 3 May Duke John of Brabant and Count Heinrich of Luxembourg both cross the border at the heads of large forces, 7,000 and 4,000, respectively. Brabant routes the peasant army on the 8th, but then the northern army then lays siege to Gembloux.

All the way back in 1296, when Caterine had first departed for Rhomaion, the two lords had planned the partition of Namen along the Meuse, to be undertaken at the first opportunity. Why they did not move in 1301 or 1307 can most likely be chalked up to the irregularity of news from the east. However, now that their plan was in action, both lords moved quickly and overwhelmed what few pockets of resistance there were in the county by the 11th, bar only the embattled Gembloux.

Summer

A rossalia epidemic sweeps Konstantinoupoli in July, hitting unusually hard amongst the upper class. The despotoi Sabbas and Ioannes, eleven and four, both fall ill. Ioannes passes on 24 July and is buried in the mausoleum of the Church of Christ Pantokrator, alongside the former Empress Dowager, who had passed in 1303. Sabbas recovers with slight hearing damage.

Word of the rising Namen reaches the capital on 29 July. Alexios calls up 1,500 infantry from Kriti and 500 Turkish auxiliaries for the purposes of putting down what was believed to be ‘only’ a peasant revolt. They launch from Monemvasia on 17 August, commanded by the young and eager Manouel Tagaris.

Word of the follow-up invasion only reaches the Rhomans when Tagaris and his expedition land at Messina in Sicily on 30 August. The young general tries to press on, but a storm rises from the Italian coast and forces them back to the island, effectively ending the campaign for 1312.

Autumn

King Philippe IV camps at Montpellier with his sons Philippe and Charles, several of his dukes and a force of 7,000 knights and 16,000 infantry. They were the French section of the Tenth Crusade, and had intended to sail to Sicily to link up with the Iberians. However, they had been slowed by rough terrain and had been unable to sail before winter set in.

Winter

A daughter is born to Sancia and Alexios, named Demetria. The girl is very ill on birth, but the Imperial doctors are able to stabilize her and she is able to pull through.

Spring

A peasant revolt begins in far-off Namen in mid-April, initially protesting the heavy taxes laid upon the march before devolving into a wandering mob with vague ideas of self-governance. They lay siege to Namen on the 26th of April, breaking down the gates on the 28th before storming into the city and killing almost everyone inside. A few dozen guards, mostly old retainers of Caterine, fall back with the few surviving de Courtenays to the fortified Abbey of Gembloux, on the border with the Duchy of Brabant. Calls for aid to the neighboring Counties of Loon and Hainaut go unanswered, but on 3 May Duke John of Brabant and Count Heinrich of Luxembourg both cross the border at the heads of large forces, 7,000 and 4,000, respectively. Brabant routes the peasant army on the 8th, but then the northern army then lays siege to Gembloux.

All the way back in 1296, when Caterine had first departed for Rhomaion, the two lords had planned the partition of Namen along the Meuse, to be undertaken at the first opportunity. Why they did not move in 1301 or 1307 can most likely be chalked up to the irregularity of news from the east. However, now that their plan was in action, both lords moved quickly and overwhelmed what few pockets of resistance there were in the county by the 11th, bar only the embattled Gembloux.

Summer

A rossalia epidemic sweeps Konstantinoupoli in July, hitting unusually hard amongst the upper class. The despotoi Sabbas and Ioannes, eleven and four, both fall ill. Ioannes passes on 24 July and is buried in the mausoleum of the Church of Christ Pantokrator, alongside the former Empress Dowager, who had passed in 1303. Sabbas recovers with slight hearing damage.

Word of the rising Namen reaches the capital on 29 July. Alexios calls up 1,500 infantry from Kriti and 500 Turkish auxiliaries for the purposes of putting down what was believed to be ‘only’ a peasant revolt. They launch from Monemvasia on 17 August, commanded by the young and eager Manouel Tagaris.

Word of the follow-up invasion only reaches the Rhomans when Tagaris and his expedition land at Messina in Sicily on 30 August. The young general tries to press on, but a storm rises from the Italian coast and forces them back to the island, effectively ending the campaign for 1312.

Autumn

King Philippe IV camps at Montpellier with his sons Philippe and Charles, several of his dukes and a force of 7,000 knights and 16,000 infantry. They were the French section of the Tenth Crusade, and had intended to sail to Sicily to link up with the Iberians. However, they had been slowed by rough terrain and had been unable to sail before winter set in.

Last edited:

1313

Eparkhos

Banned

1313

Winter

Tagaris, hoping to reach Namen before Glemboux falls, decides to risk the early-spring crossing of the Mediterranean and sets out from Messina on 12 February. Nature is with the Rhomans, however, and they are not troubled by storms as they sail. The Rhomans sail west along the northern coast of the island before jumping across to Sardinia, landing there on 23 February. They then sail up the coast of that island and Corsica, pausing on Bastia on 14 March to ride out a storm before carrying on.

On 25 February, the Brabanters use the coming of the local peasants to mass to attack Gembloux, briefly taking the vestibule before being driven back. This defiling of the local sanctuary only worsens the relations between the Brabanters and the local Namenese peasants.

Spring

King Phillippe departs Montpellier on 11 March, sailing east along the coast with his entire force. However, the same storm that forced Tagaris to hold on Bastia hits the French and drives them ashore on the Ile de Levant. Roughly a thousand of the Crusaders, mostly knights, drown and a good deal of the fleet is heavily damaged. While completing repairs, Tagaris’ fleet happens to pass by going the opposite way. The Rhoman commander briefly puts ashore, seeing an opportunity to shorten his voyage. He introduces himself as a representative of Alexios leading an army to put down a peasant revolt in Namen, playing up the likeliness of said rising spreading into France and offering the French king an opportunity to establish a Latin mission in Konstantinoupoli in exchange for access to the Rhone. Philippe accepts, issuing a decree allowing the Rhomans access to ‘...the rivers of western France..’. Tagaris then continues on, reaching the mouth of the river on the 15th.

Jaime II lands on Sicily with 500 knights and 12,000 infantry on 17 March. However, wary of depleting the island’s foodstocks, he sends a message to Alexios asking for permission to land his army on Kriti and then travel to Konstantinoupoli with a small group of retainers. Alexios accepts as soon as he gets the message.

Nikolya crosses the Tauruses with 15,000 horse archers and 20,000 infantry in mid-April. He quickly storms through the mountains, reaching Sivas on 21 April and taking it by storm two days later. He then sweeps down the left bank of the Kizilirmak River towards Konya, scattering the few militias that try to oppose him. Mesut, frantic to hold the Mongols off long enough for the populace of Konya to evacuate and having flashbacks to the last invasion, rides with the ~300 palace guards of the city and 4,000 light infantry to reinforce the primary fortress between the invaders and the capital; Kayseri. Sardar Orhan, the 35-year old crown prince, rides west to gather an army to repulse the invaders.

The Turks arrive in the city on 26 April, only a day before Nikolya and his entire host arrives. An initial assault fails with heavy Mongolian losses, and the Il-Khan orders siege works to be set up. That night, Nikolya’s generals are able to convince him not to bypass the city and push on to Konya, reminding him of what happened the last time he bypassed a Turkish fortification. He reluctantly agrees to begin a siege, but orders daily assaults to speed up progress. During the first week, the Mongols almost break through the walls several times only to be driven back by desperate charges from the garrison, twice joined by the women and elderly of Kayseri. On the 5th of May, the Mongols prepare for a final assault and begin launching flaming projectiles over the walls directly across from the gate and undermine that section of the wall, hoping to divide the garrison’s efforts. Mesut swears the entire city’s populace to die before surrendering.

But then, on the dawn of the 6th, a frantic rider enters the Mongolian camp. The governors of Azerbaijan, Khorasan, Dihistan, Gilan and Tabaristan had risen in a religious rebellion against the Il-Khan in late April and were currently beating down the gates of Tabriz. Nikolya flips out and turns and marches back to Eran, leaving his brother Khitai and 10,000 infantry behind to continue the siege.

Khitai was very different from his elder brother; he was known in most of the Il-Khanate for his caution and timidity. Rather than assaulting the city on the 6th as Nikolya had planned, he instead orders more flamming objects chucked over the wall in an attempt to smoke the defenders out, encircling the city with 5,000 men and keeping the other half in reserve to jump on any breakout attempts. On the 8th, after two days with no-one emerging from the city, Khitai orders the reserves to enter the city through the gates, on the northern side of the city. A few minutes after they do, the population of the city, roughly 15,000 including the garrison, bursts out of the southern entrance and through the inattentive Mongols. The soldiers spread out and form a circular perimeter around the civilians, then start moving as quickly as they can for the nearby cave-riddled Mount Erciyas three miles to the south. Khitai barrels after him with what little cavalry he had, but they are almost all melee and are unable to close under heavy arrow fire. The infantry are unable to catch up with the fleeing Turks until they reach the lower slopes of the mountain, when Khitai orders them back in fear of an ambush.

With the city in Mongolian hands, Khitai orders the few remaining buildings burned and the walls pulled down to avoid having a hostile fortress in his rear. He then marches north-east along the Kizilirmak towards Lake Tuz. They reach the lake on the 14th, freshly out of water. Khitai had ordered the army to carry little water to try to speed their advance across the plateau. Upon realizing that Lake Tuz was salt water and they could not replenish their reserves, the Mongolians turn and race back to the river. It was only a day’s march away, but with the high temperature and little shade of the plateau, several hundred men die of heatstroke before they are able to return.

This delay in movement allows Mesut and his men to book it for Konya, arriving on the 18th. The Sultan expels the civilians of the city and orders them to march west to the mountains, then gathers up the garrisons and militia of the surrounding cities and countryside into the city. The buildings outside the walls are torn down and the materials dragged inside to reinforce the gates and walls. There were 7,000 men within the walls, and enough food to hold out for five months, more than long enough for Orhan to arrive with a relief force.

The Sardar, meanwhile, had sent riders to the garrison commanders of all of the south-west to gather every man they could and meet at Saporda (Isparta). He himself carried on to the Rhoman border, where he sent a frantic messenger to Konstantinoupoli begging for aid, dated 1st of May. In said message, he offered a quarter of the Sultanate’s annual revenue in exchange for sending help. This may seem unusual, but keep in mind that Orhan was unaware of Nikolya turning away and still believed that 35,000 Mongolian fanatics were bearing down on the capital. Alexios sees the message but dismisses it, remembering what happened the last time he helped the Turks against an invading Mongolian horde. After waiting a month for a response, Orhan turns and rides back to Saporda, where an army of 18,000 had gathered. However, rather than marching west to assault the Mongols, he instead chose to hold at the city. He justified this to his men as trying to trap the invaders between a rock (Konya) and a hard place (the army), but this did not stop rumors of cowardice from spreading through the ranks.

Meanwhile, Khitai brought more water on his second march on Konya, arriving outside the city on 22 May. He sends a message to the Sultan, offering to spare his life and that of his family if he surrenders. Mesut returns the man via catapult. Rather than attempting to batter down the walls, Khitai sets up for a siege.

Summer

Jaime II and his entourage, 20 knights and ~125 servants, arrive in Konstantinoupoli on 11 June. They are housed in the Mangana Palace with the Imperial family, as the only other non-ruined palace in the city was occupied by the Serbians. The Aragonese settle in fairly well, and with some persuasion by Jaime Alexios agrees to allow the Crusader lords to stay in the capital, if they are willing to leave their armies on Kriti. The emperor also pointed out that Jerusalem was held by a (demi-)Christian, so Egypt would probably be a better target.

Philippe reaches Kriti in late June, following after Jaime. However, he suspects a trap and refuses to move on to Konstantinoupoli, staying on Kriti with his army. He is unwilling to let the Aragonese king have sole access to the Emperor, however, so he dispatches his son Philippe the Tall to the capital with a small group of retainers. The Prince arrives on 7 July.

On 11 July, Khitai and his men are woken by Orhan’s army just outside their camp. The Mongolian camp was semi-fortified, but even with these defenses they were soon overwhelmed. Khitai orders his men to retreat towards a nearby creek-bed, setting fire to their tents to slow down the Turkish advance. However, the Turkish light horse are able to swing out from the city walls and into the creek bed, dividing the retreating Mongolian line in two. The leading edge, roughly 300 men, are able to continue their flight; the ~1500 other men of the retreating group are massacred, Khitai among them. The Mongolian defense quickly dissolves, the soldiers scattering across the land around Konya. Over the next week, many are ridden down or die of thirst, but a group of 800, mostly Vainakhs and Azeris, are able to regroup on the Kizilirmak. They elect a commander, a minor Vainakh noble named Ramzan khant Axmad-Xazi. Knowing that they would likely be punished for the expedition’s failure, the survivors instead begin moving north along the river’s left bank, hoping to reach the Empire and a refuge from the Turks.

In far-off Bulgaria, the Tsarina gives birth to a son, named Ivan, on 27 July. This is a proverbial shock to the system, as it had been believed that Sofiya Asen was infertile since 1301. There is, of course, speculation that the actual issues were on the Tsar’s part and the new heir was the product of an affair, but these are pointedly ignored by the government. The birth of an heir also destabilizes the domestic political situation, as there was an unspoken agreement that Georgi Terter’s son Todor would ascend the throne after Sofiya’s death. Both pro-Asen and pro-Terter noble factions begin to form.

In early August, a group of Mamluk slavers raid Kypros. The island’s small garrison isn’t able to drive them off, and they withdraw after a week with roughly 1,000 captives.

The Empress gives birth to another son on 27 August. He is, like Sabbas, named after an Anatolian folk hero, the supercentenarian saint Kharalampos of Magnesia. Patriarch Nikolaos is cajoled into allowing Jaime to stand as godfather, and the christening is set for 4 October.

Autumn

Over the course of late summer and early to mid-autumn a slow trickle of Crusader knights arrives in Konstantinoupoli. Most are landowners at the heads of Crusader armies, which are left on Kriti. Food on the island begins to run low, and in late August grain ships begin to travel from the fertile western coast to the island, feeding Rhoman and Latin alike.

On 14 September, Tagaris lands at Pairelle, a half-mile south of the city of Namen. The landing occurs at night, and the Rhomans quickly advance up the left bank of the river towards the city. Three cannons had been brought with the expedition, and these were set up on the heights across the Sambre from Namen. At dawn they open fire, raining large balls of led down on the city. They are targeted at the walls, as Tagaris was unwilling to damage the city’s weaving facilities. However, the destruction of the walls demoralizes the Brabanter garrison enough to surrender. The Rhomans occupy it, then Tagaris detaches the Turkish auxiliaries and rides for Gembloux. Duke John, suspecting that these were only the front riders of a much larger force, withdraws from Gembloux on the 15th and asks to treat with Tagaris. In exchange for surrendering his claim to Namen, the border between Brabant and Rhomaion would be redrawn along the Burdinal Creek, giving Brabant an extra ½ mile of land. Even though Tagaris has no authority, John agrees and withdraws back across the border.

Tagaris then turns back and crosses the Meuse, attacking the Louxembourgish in their camp. The Rhomans route them, which is enough to discourage Heinrich from further fighting. Tagaris cedes the land south of Boreuville to Louxembourg before retiring to Namen on the 21st.

Winter

Tagaris, hoping to reach Namen before Glemboux falls, decides to risk the early-spring crossing of the Mediterranean and sets out from Messina on 12 February. Nature is with the Rhomans, however, and they are not troubled by storms as they sail. The Rhomans sail west along the northern coast of the island before jumping across to Sardinia, landing there on 23 February. They then sail up the coast of that island and Corsica, pausing on Bastia on 14 March to ride out a storm before carrying on.

On 25 February, the Brabanters use the coming of the local peasants to mass to attack Gembloux, briefly taking the vestibule before being driven back. This defiling of the local sanctuary only worsens the relations between the Brabanters and the local Namenese peasants.

Spring

King Phillippe departs Montpellier on 11 March, sailing east along the coast with his entire force. However, the same storm that forced Tagaris to hold on Bastia hits the French and drives them ashore on the Ile de Levant. Roughly a thousand of the Crusaders, mostly knights, drown and a good deal of the fleet is heavily damaged. While completing repairs, Tagaris’ fleet happens to pass by going the opposite way. The Rhoman commander briefly puts ashore, seeing an opportunity to shorten his voyage. He introduces himself as a representative of Alexios leading an army to put down a peasant revolt in Namen, playing up the likeliness of said rising spreading into France and offering the French king an opportunity to establish a Latin mission in Konstantinoupoli in exchange for access to the Rhone. Philippe accepts, issuing a decree allowing the Rhomans access to ‘...the rivers of western France..’. Tagaris then continues on, reaching the mouth of the river on the 15th.

Jaime II lands on Sicily with 500 knights and 12,000 infantry on 17 March. However, wary of depleting the island’s foodstocks, he sends a message to Alexios asking for permission to land his army on Kriti and then travel to Konstantinoupoli with a small group of retainers. Alexios accepts as soon as he gets the message.

Nikolya crosses the Tauruses with 15,000 horse archers and 20,000 infantry in mid-April. He quickly storms through the mountains, reaching Sivas on 21 April and taking it by storm two days later. He then sweeps down the left bank of the Kizilirmak River towards Konya, scattering the few militias that try to oppose him. Mesut, frantic to hold the Mongols off long enough for the populace of Konya to evacuate and having flashbacks to the last invasion, rides with the ~300 palace guards of the city and 4,000 light infantry to reinforce the primary fortress between the invaders and the capital; Kayseri. Sardar Orhan, the 35-year old crown prince, rides west to gather an army to repulse the invaders.

The Turks arrive in the city on 26 April, only a day before Nikolya and his entire host arrives. An initial assault fails with heavy Mongolian losses, and the Il-Khan orders siege works to be set up. That night, Nikolya’s generals are able to convince him not to bypass the city and push on to Konya, reminding him of what happened the last time he bypassed a Turkish fortification. He reluctantly agrees to begin a siege, but orders daily assaults to speed up progress. During the first week, the Mongols almost break through the walls several times only to be driven back by desperate charges from the garrison, twice joined by the women and elderly of Kayseri. On the 5th of May, the Mongols prepare for a final assault and begin launching flaming projectiles over the walls directly across from the gate and undermine that section of the wall, hoping to divide the garrison’s efforts. Mesut swears the entire city’s populace to die before surrendering.

But then, on the dawn of the 6th, a frantic rider enters the Mongolian camp. The governors of Azerbaijan, Khorasan, Dihistan, Gilan and Tabaristan had risen in a religious rebellion against the Il-Khan in late April and were currently beating down the gates of Tabriz. Nikolya flips out and turns and marches back to Eran, leaving his brother Khitai and 10,000 infantry behind to continue the siege.

Khitai was very different from his elder brother; he was known in most of the Il-Khanate for his caution and timidity. Rather than assaulting the city on the 6th as Nikolya had planned, he instead orders more flamming objects chucked over the wall in an attempt to smoke the defenders out, encircling the city with 5,000 men and keeping the other half in reserve to jump on any breakout attempts. On the 8th, after two days with no-one emerging from the city, Khitai orders the reserves to enter the city through the gates, on the northern side of the city. A few minutes after they do, the population of the city, roughly 15,000 including the garrison, bursts out of the southern entrance and through the inattentive Mongols. The soldiers spread out and form a circular perimeter around the civilians, then start moving as quickly as they can for the nearby cave-riddled Mount Erciyas three miles to the south. Khitai barrels after him with what little cavalry he had, but they are almost all melee and are unable to close under heavy arrow fire. The infantry are unable to catch up with the fleeing Turks until they reach the lower slopes of the mountain, when Khitai orders them back in fear of an ambush.

With the city in Mongolian hands, Khitai orders the few remaining buildings burned and the walls pulled down to avoid having a hostile fortress in his rear. He then marches north-east along the Kizilirmak towards Lake Tuz. They reach the lake on the 14th, freshly out of water. Khitai had ordered the army to carry little water to try to speed their advance across the plateau. Upon realizing that Lake Tuz was salt water and they could not replenish their reserves, the Mongolians turn and race back to the river. It was only a day’s march away, but with the high temperature and little shade of the plateau, several hundred men die of heatstroke before they are able to return.

This delay in movement allows Mesut and his men to book it for Konya, arriving on the 18th. The Sultan expels the civilians of the city and orders them to march west to the mountains, then gathers up the garrisons and militia of the surrounding cities and countryside into the city. The buildings outside the walls are torn down and the materials dragged inside to reinforce the gates and walls. There were 7,000 men within the walls, and enough food to hold out for five months, more than long enough for Orhan to arrive with a relief force.

The Sardar, meanwhile, had sent riders to the garrison commanders of all of the south-west to gather every man they could and meet at Saporda (Isparta). He himself carried on to the Rhoman border, where he sent a frantic messenger to Konstantinoupoli begging for aid, dated 1st of May. In said message, he offered a quarter of the Sultanate’s annual revenue in exchange for sending help. This may seem unusual, but keep in mind that Orhan was unaware of Nikolya turning away and still believed that 35,000 Mongolian fanatics were bearing down on the capital. Alexios sees the message but dismisses it, remembering what happened the last time he helped the Turks against an invading Mongolian horde. After waiting a month for a response, Orhan turns and rides back to Saporda, where an army of 18,000 had gathered. However, rather than marching west to assault the Mongols, he instead chose to hold at the city. He justified this to his men as trying to trap the invaders between a rock (Konya) and a hard place (the army), but this did not stop rumors of cowardice from spreading through the ranks.

Meanwhile, Khitai brought more water on his second march on Konya, arriving outside the city on 22 May. He sends a message to the Sultan, offering to spare his life and that of his family if he surrenders. Mesut returns the man via catapult. Rather than attempting to batter down the walls, Khitai sets up for a siege.

Summer

Jaime II and his entourage, 20 knights and ~125 servants, arrive in Konstantinoupoli on 11 June. They are housed in the Mangana Palace with the Imperial family, as the only other non-ruined palace in the city was occupied by the Serbians. The Aragonese settle in fairly well, and with some persuasion by Jaime Alexios agrees to allow the Crusader lords to stay in the capital, if they are willing to leave their armies on Kriti. The emperor also pointed out that Jerusalem was held by a (demi-)Christian, so Egypt would probably be a better target.

Philippe reaches Kriti in late June, following after Jaime. However, he suspects a trap and refuses to move on to Konstantinoupoli, staying on Kriti with his army. He is unwilling to let the Aragonese king have sole access to the Emperor, however, so he dispatches his son Philippe the Tall to the capital with a small group of retainers. The Prince arrives on 7 July.

On 11 July, Khitai and his men are woken by Orhan’s army just outside their camp. The Mongolian camp was semi-fortified, but even with these defenses they were soon overwhelmed. Khitai orders his men to retreat towards a nearby creek-bed, setting fire to their tents to slow down the Turkish advance. However, the Turkish light horse are able to swing out from the city walls and into the creek bed, dividing the retreating Mongolian line in two. The leading edge, roughly 300 men, are able to continue their flight; the ~1500 other men of the retreating group are massacred, Khitai among them. The Mongolian defense quickly dissolves, the soldiers scattering across the land around Konya. Over the next week, many are ridden down or die of thirst, but a group of 800, mostly Vainakhs and Azeris, are able to regroup on the Kizilirmak. They elect a commander, a minor Vainakh noble named Ramzan khant Axmad-Xazi. Knowing that they would likely be punished for the expedition’s failure, the survivors instead begin moving north along the river’s left bank, hoping to reach the Empire and a refuge from the Turks.

In far-off Bulgaria, the Tsarina gives birth to a son, named Ivan, on 27 July. This is a proverbial shock to the system, as it had been believed that Sofiya Asen was infertile since 1301. There is, of course, speculation that the actual issues were on the Tsar’s part and the new heir was the product of an affair, but these are pointedly ignored by the government. The birth of an heir also destabilizes the domestic political situation, as there was an unspoken agreement that Georgi Terter’s son Todor would ascend the throne after Sofiya’s death. Both pro-Asen and pro-Terter noble factions begin to form.

In early August, a group of Mamluk slavers raid Kypros. The island’s small garrison isn’t able to drive them off, and they withdraw after a week with roughly 1,000 captives.

The Empress gives birth to another son on 27 August. He is, like Sabbas, named after an Anatolian folk hero, the supercentenarian saint Kharalampos of Magnesia. Patriarch Nikolaos is cajoled into allowing Jaime to stand as godfather, and the christening is set for 4 October.

Autumn

Over the course of late summer and early to mid-autumn a slow trickle of Crusader knights arrives in Konstantinoupoli. Most are landowners at the heads of Crusader armies, which are left on Kriti. Food on the island begins to run low, and in late August grain ships begin to travel from the fertile western coast to the island, feeding Rhoman and Latin alike.

On 14 September, Tagaris lands at Pairelle, a half-mile south of the city of Namen. The landing occurs at night, and the Rhomans quickly advance up the left bank of the river towards the city. Three cannons had been brought with the expedition, and these were set up on the heights across the Sambre from Namen. At dawn they open fire, raining large balls of led down on the city. They are targeted at the walls, as Tagaris was unwilling to damage the city’s weaving facilities. However, the destruction of the walls demoralizes the Brabanter garrison enough to surrender. The Rhomans occupy it, then Tagaris detaches the Turkish auxiliaries and rides for Gembloux. Duke John, suspecting that these were only the front riders of a much larger force, withdraws from Gembloux on the 15th and asks to treat with Tagaris. In exchange for surrendering his claim to Namen, the border between Brabant and Rhomaion would be redrawn along the Burdinal Creek, giving Brabant an extra ½ mile of land. Even though Tagaris has no authority, John agrees and withdraws back across the border.

Tagaris then turns back and crosses the Meuse, attacking the Louxembourgish in their camp. The Rhomans route them, which is enough to discourage Heinrich from further fighting. Tagaris cedes the land south of Boreuville to Louxembourg before retiring to Namen on the 21st.

The Romans had just stumbled across the largest gold deposit in Europe, with 435 MILLION TONS of gold.

This figure is off by at least three orders of magnitude. Cumulative gold production through all of history is only 190,000 tonnes, 2/3 of which has been produced since 1950. See How much gold has been mined?

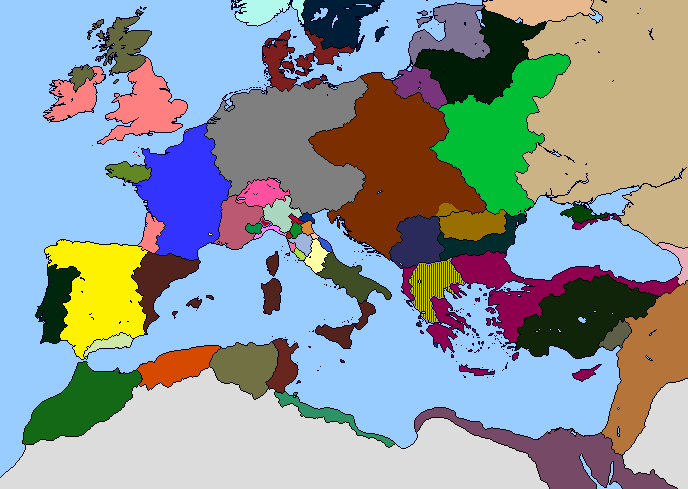

Switzerland in 1305 includes only the three "Forest Cantons", Uri, Unterwalden, and Schwyz. The map shows the outline of 1500 or so.View attachment 473944

A visual aid for the wider world:

Last edited:

Eparkhos

Banned

This figure is off by at least three orders of magnitude. Cumulative gold production through all of history is only 190,000 tonnes, 2/3 of which has been produced since 1950. See

How much gold has been mined?

Switzerland in 1305 includes only the three "Forest Cantons", Uri, Unterwalden, and Schwyz. The map shows the outline of 1500 or so.

I got that number from the website of the company that owns that mine. I don't remember what site it was and I don't have the link as it was on my old computer. If I find it, I'll link it. Now that I think of it, I think it might have been 435,000 tons, not 435,000,000. Sorry.

As for Switzerland, that was a mistake. I'll correct it when I can find a better map.

1314

Eparkhos

Banned

1314

Winter

1314 marks the end of the 10-year truce between Rum and Rhomaion, and both parties spend the winter of 1313-1314 drawing up battle plans. Tentative peace feelers are sent between Konya and Konstantinoupoli, but Alexios is eager to test the new, larger Rhoman army against the Turks, especially as it has been bolstered by Serbian and Latin volunteers.

The total Rhoman troop figures are roughly 80,000, of which 50,000 are Rhomans. This force can be fairly accurately divided by type, with their being ~40,000 infantry (~25,000 Rhomans), ~35,000 light cavalry (~25,000 Rhomans), and ~5,000 knights and kataphraktoi. The Turkish men number ~50,000 all together, of which ~15,000 are infantry and ~35,000 are light cavalry.

Despite their numerical inferiority, Mesut wished to strike quickly and break the morale of the Rhoman army so he can turn and face Nikolya with the full strength of Rum. As such, he divided his army into three groups: His personal army, numbering 10,000 infantry and 15,000 light cavalry, was kept at Konya, as he and his advisors would be going for a knockout blow against the capital. The Sardar leads a force of 5,000 infantry and 10,000 light horse, positioned at Kara Hissar near the western border. The remainder, 10,000 ghazi infantry led by a mujahideen named Qara Ümit, are positioned at Ankyra. Given that the Basileus could not march with the entirety of the Rhoman military against Rum, Mesut believed that the invading army would be composed primary of light horse, and thus would be invading via the plateau. As such, these two armies were positioned so as that were Alexios to invade from that direction he would have to either face them combined in the field or lay siege to one’s base city while the other two converged on him. It was the same in the west, where he would either have to strike at Kara Hissar or Konya.

The Rhoman plan, however, was decidedly more aggressive. There were to be four army groups, two large, two small (Although this is relative; the size of the smallest group was the same as the entire army during the reign of Andronikos II). Alexios would lead the northern large group, based in Dorylaion, across the plateau to Ankyra, while the southern large group, under the command of the young but experienced general Isaakios Abranetzis, would march south-east from Laodikea to the port city of Attaleia. After taking those cities, the armies were to march on Konya and envelop any defenders there. The smallest group, operating from Proussa, would intercept any Turkish armies moving west while the fourth group, based in Amisos, would close the passes into Paphlagonia.

But as always, no plan survives contact with the enemy.

Spring

The Crusaders in Konstantinoupoli split into three camps in mid-March; One, led by Jaime of Aragon, wishes to change course to Egypt as Jerusalem was already held by a Christian, albeit by an Oriental one. The second, led by Prince Philippe, wish to continue on to Jerusalem; The third, led by Raoul of Brienne, a claimant to the throne of the Latin Empire, wishes to go all Fourth Crusade. The latter group are executed en masse in the city square on 28 March.