XXVII: The Lincoln Administration

To the relief of Lincoln, the country did not dissolve the moment he took the oath of office. There were a few within the Deep South that called for secession, but with Yancey Rebellion so fresh in the minds of the general public the established leaders within the region were not eager to take so radical an action over so moderate of a man. This is not to say they fully trusted Lincoln, as they were constantly looking for deception and traps in whatever actions he took, but the calls for disunion were not ringing from the halls of Congress, at least not in response to him. Lincoln had become a Unionist, as members of the Constitutional Union Party were increasingly being referred to as, and he was determined to uphold the party's promise that the Union and the Constitution must be upheld and preserved.

Of course, this brought him into conflict with many men who just three years prior had been calling for his election to the vice-presidency. The Senate lacked an effective majority as it stood divided between 34 Republicans, 31 Democrats, and 3 Unionists. Only Lincoln's previous diplomacy as vice-president allowed William K. Sebastian to stay on as president pro tempore. This highlighted, of course, the inability of Lincoln to appoint a vice-president to break the deadlock. To this end Lincoln would quietly try to maneuver behind the scenes to pass legislation allowing him to do so, but Republicans still bitter over his abandonment of the party were in no mood to perform him any favors, especially if it would further weaken their position. Thus, Lincoln found himself constrained to moderation to achieve a degree of cross-over support from his two opposition parties. Of course, moderate man that he was, this would not hinder Lincoln too much, although it would find him unable to pass what he hoped would be his signature piece of legislation.

This was the Homestead Bill, by which he sought to encourage settlement of the West by poor farmers by offering them tracts of land in exchange for them developing and enriching them. Ultimately, the ambition would die at the hands of Southerners and Republicans. The former group feared it as a plot to establish the land as free soil territory, even as Lincoln denied popular sovereignty would be attached to it. Many Midwest Republicans would go along with it, knowing of its popularity with voters at home, but New England Republicans hoping to deny Lincoln a victory and were angered by his refusal to guarantee the land as free-soil worked. Together, the unlikely allies worked together to kill the bill. It would pass the House over the objections of Speaker Lovejoy, but would meet its death in the polarized Senate. Thus, the bill was left to languish until a later time.

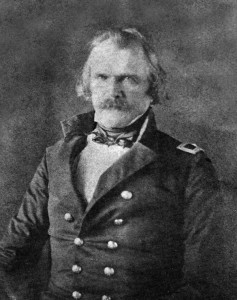

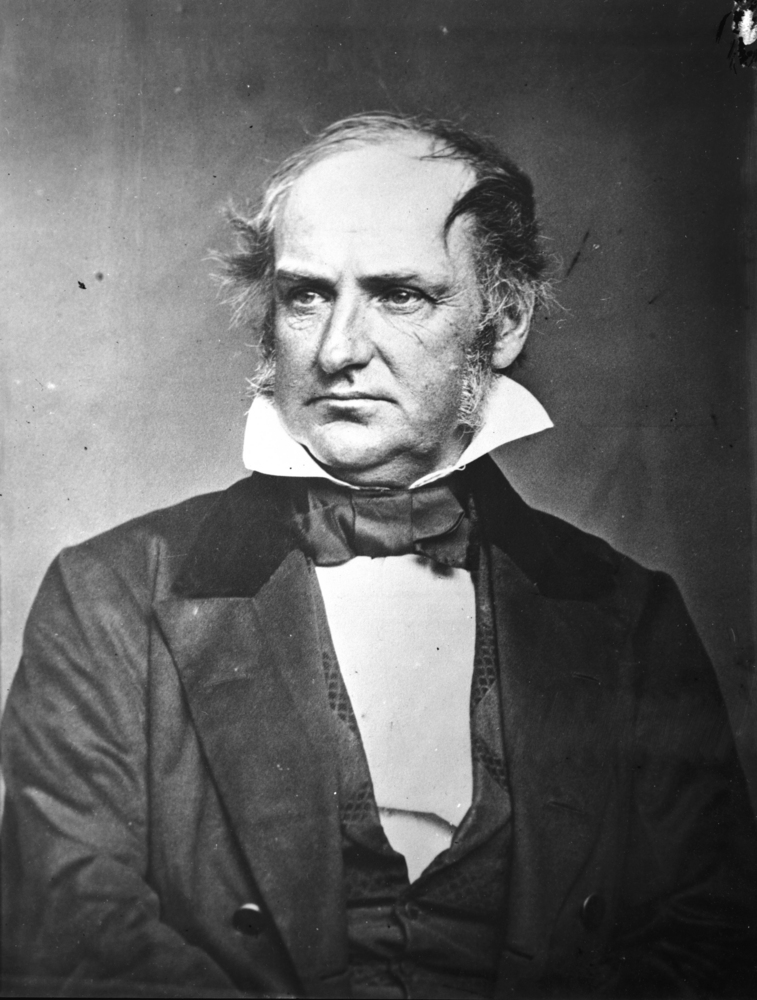

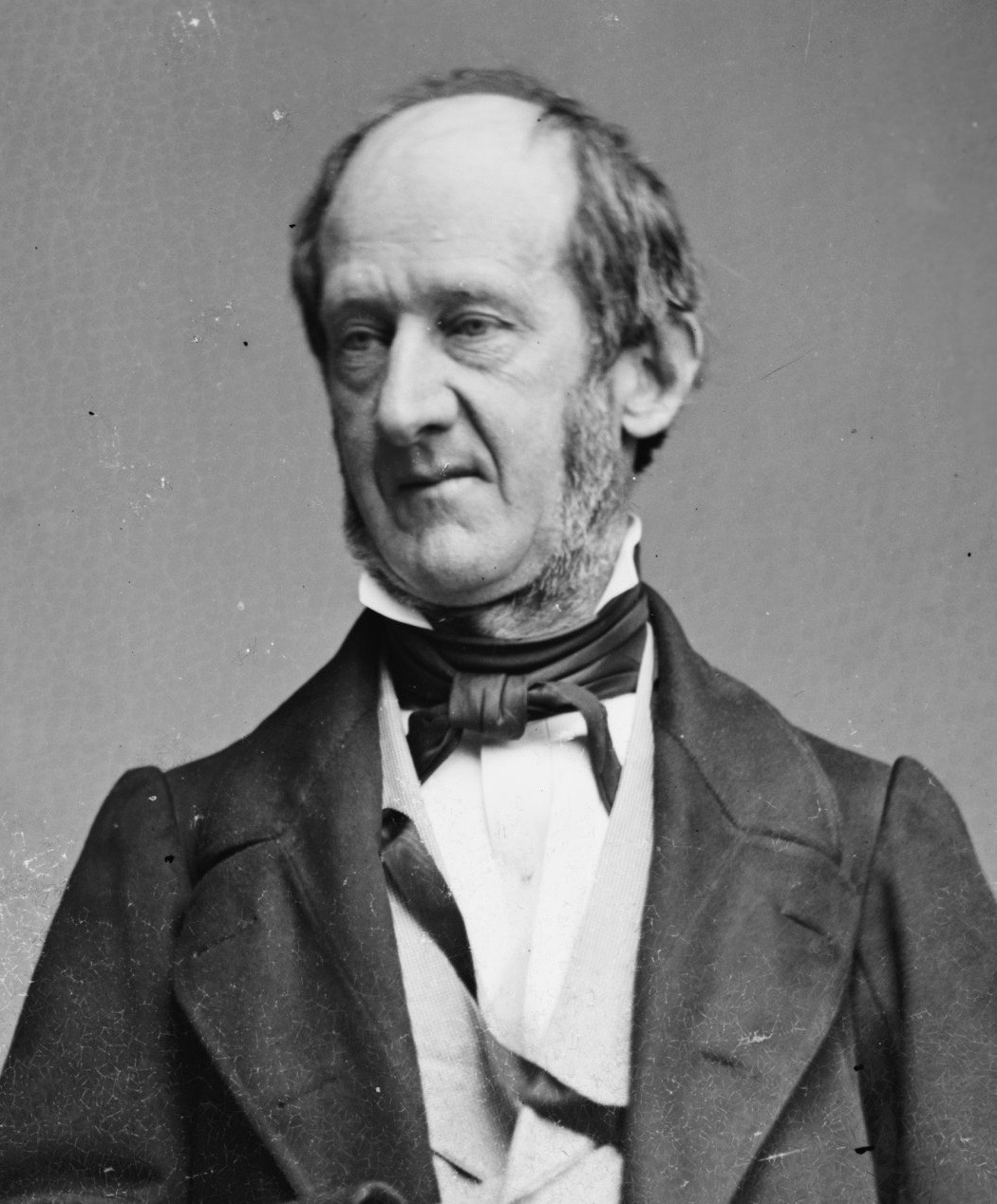

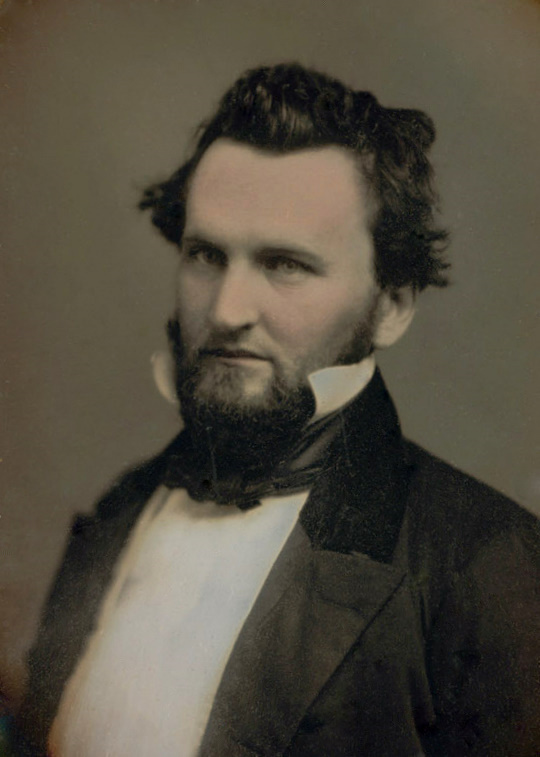

President Pro Tempore William K. Sebastian and Speaker of the House Owen Lovejoy

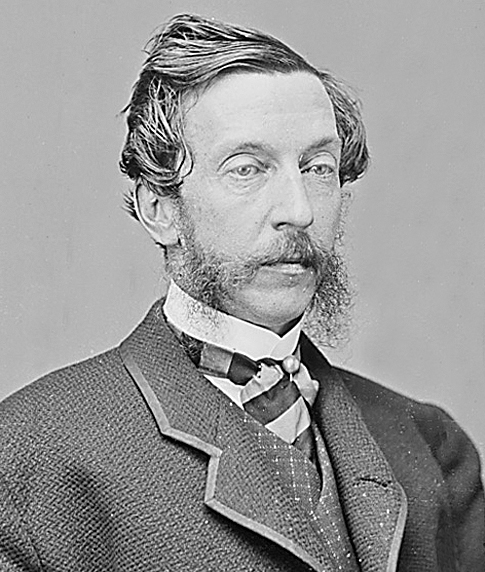

Lincoln did manage to secure one victory from the encounter, however. Throughout his efforts to get the bill passed, Lincoln had sent out feelers to members of the opposition parties in the Senate to at first try and gain their support for passage. Later, however, this initiative would develop into an effort to convince them to switch parties. His primary targets in this effort would be Republican Edward Baker of Oregon and Democrats Lazarus Powell of Kentucky, George E. Pugh of Ohio, James W. Nesmith of Oregon, and most notably Stephen Douglas of Illinois. In his efforts, the first two would successfully be convinced, the third would decline outright, but most the latter two presented the most interesting proposition. Douglas knew that despite his victory in the 1860 nominating convention, the forces of the South and the Doughfaces within the party were still very strong, and had only been reinforced by his defeat in that election. His subsequent actions, often in contradiction with the will of the party establishment, had further isolated him and his faction within the party.

Thus, Douglas was left with a choice. He could either attempt to hold his ground in a party he formerly led but that was rapidly moving away from him or he could jump into a new, less-established party that he found himself increasingly agreeing with and who were eager to have him with his name recognition. Ultimately, Douglas proved he was still a fighter, but kept the door open on Lincoln's advances. He declined to switch affiliation at the moment, claiming to wait until the 1864 Democratic presidential nominating convention to measure the degree of influence he maintained with the organization. He said that the results of that event would determine whether he would remain a Democrat or switch to the Unionists. Nesmith, one of Douglas' closest affiliates within the Senate, agreed to abide with Douglas' decision. Glad that at least the door remained open, Lincoln agreed to keep the plans of the two men private until they had made their decision.

Regardless of their decision, he found himself in a stronger position. Baker and Powell, who both knew there was a strong likelihood of them facing a Unionist controlled (or at least influenced) assembly electing them come 1864, decided to switch ships on November 13, 1863, and hope for re-election. Lincoln now found himself dealing with a Senate consisting of 33 Republicans, 30 Democrats, and 5 Unionists, meaning that he could position the five members of his party in either camp to give a majority to either Republicans or Democrats. This, of course, certainly made them more responsive to his prerogatives as both parties sought to influence the Unionists to support them.

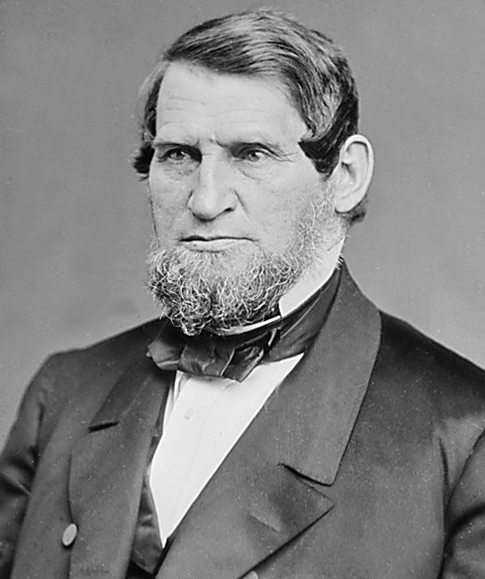

Lincoln's old friend and ally Edward Baker

Lincoln would find more success dealing with his cabinet than Congress. Shortly after Crittenden's death, a shakeup ensued. Secretary of State Sam Houston and Secretary of the Treasury Francis Granger, both of who had been contemplating resignation due to their old age even before the precipitous decline of Crittenden's health, decided to take the opening of a new administration to turn in their resignation. Likewise, Secretary of the Navy William A. Graham, who did not want to serve under a Republican (even a former one) and who was eyeing the upcoming 1864 Senate election in his home state of North Carolina, resigned. Postmaster General Alexander H. Stephens was also reportedly planning his resignation, but a personal appeal from Lincoln, his old colleague and friend from the House, convinced him to stay in office. As a result, Lincoln was left with three vacancies within his cabinet, and he used the opportunity well.

All three men he would appoint were moderate Republicans, which not only ensured safe passage through the Senate (as this was before he had expanded the number of Unionists), but also signaled to other moderate Republicans that there was a place for them within the Unionist Party. For the State Department, Lincoln selected the man he had previously supported at the 1860 Republican National Convention: Edward Bates. Bates was already put off by the increasingly radical nature of the Republican Party, and thus was eager to accept what he viewed as an invitation to become a leader in the Unionist Party. For the Treasury Department, Lincoln nominated veteran politician Thomas Ewing, who had formerly held the position during the brief Harrison administration and had subsequently served as both a senator and Secretary of the Interior. Just like Bates, Ewing was eager to join the upper echelons of a party that matched his moderate views. To fill the last position as Secretary of the Navy, Lincoln appointed a rarity: North Carolina Republican Edward Stanly. By the time of his nomination, Stanly already identified with the Unionist Party, but his previous stand with the Republicans endeared him to many members of that party in the Senate and ensured a fairly easy confirmation.

If Lincoln's experiences with the legislative branch reflected the difficulties of his time in office and his experiences with the executive branches represented his triumphs, then Lincoln experiences with the judicial branch reflected both. On January 7, 1864, Associate Justice Caleb B. Smith would pass away after his almost three year tenure on the highest court in the land. Lincoln, who during his time as vice-president had proved crucial in securing Smith's approval, set to work just as vigorously to get his replacement approved. Ultimately, Lincoln would selected John A. Griswold, a man with sparse legal experience but who held a murky history of affiliations that had included all three parties in the past and remained unclear at the time of his nomination. What was most important to Lincoln, however, was his unswerving loyalty to the Union. This was followed, of course, by the expected ease of his approval. In this Lincoln would be proven right as Griswold's fluid stances and Lincoln's Senate sway ensured a swift approval.

Lincoln's other Supreme Court vacancy came on October 12, 1864 following the passing of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, and it would reflect the other nature of Lincoln's time in office. This came, of course, in the heat of the presidential election and very near to Election Day. Beyond the simple hope that their man would win and get to select the new Chief Justice if he won in November, the Republicans in the Senate also hoped to deny the Unionists the morale victory of having one of their own sitting as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Thus, despite Lincoln's pleadings and maneuverings, Lincoln's nominee, Edward Bates, who had once easily passed the Senate vote for the State Department, found himself stonewalled by Republicans with eyes set on the future. As could be said with most of Lincoln's presidency, Lincoln would have his victories, but they were far from universal.

Associate Justice John A. Griswold

.