You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Horn of Bronze--The Shaping of Fusania and Beyond

- Thread starter Arkenfolm

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 108 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 84-Down the River and Towards the Dawn: The Pathfinder Chapter 85-Down the River and Towards the Dawn: The Splendor of the East Chapter 86-In the Shadows of Only the Sun Chapter 87-To Sail Between the Worlds Chapter 88-Chasing the South Wind Map 10-North Fusania in 1244 Map 14-Cultural areas of the Misebian world in the late 13th century Map 15-Upper Misebi and the Great Lakes in the late 13th centuryI know it's probably a no brainer, but a less isolationist Japan will have a big impact in asian geopolitics.

Chapter 6-Hempen Ships, Copper Horns

-VI-

"Hempen Ships, Copper Horns"

Haruo Endou, Lords of the North: The Dena Origins of Fusania (1969) (Katorimatsu [Cathlamet, WA] University Press). Translated by Seppo Savolainen (Ilonlinna [Charlottetown, PEI] University, Vinland) 1978.

The climate changes at the end of the 5th century caused chaos in northern Fusania. The permanent villages and even towns ended up emptying out as the resources to feed them mostly vanished and the people sought better lives elsewhere. Traditionally called the Dena expansions and sometimes lumped into other ongoing migrations of Dena peoples, in modern times it has been proven that the Dena's own expansions resulted in other groups like the Ringitsu, Khaida, and Tsusha to likewise migrate. Such migrations have thus resulted in the era being called the American Migration Period, for its impact spread far beyond the territories inhabited by Dena peoples."Hempen Ships, Copper Horns"

Haruo Endou, Lords of the North: The Dena Origins of Fusania (1969) (Katorimatsu [Cathlamet, WA] University Press). Translated by Seppo Savolainen (Ilonlinna [Charlottetown, PEI] University, Vinland) 1978.

The disrupted of their lifestyle combined with their willingness to hold onto it led to the Dena to disperse from the Hentsuren, Nuklukayet, and other centers of their culture like never before. The Tachiri Culture found in that region served as a template for later cultures of the Dena. Armed with their reindeer, intensive skill at controlling key Arctic plants, and their knowledge of earthworks and waterworks, among other traits, the Dena migrated in every direction for a variety of reasons, seeking good land for their immediate kin.

Those of the Old Ringitani Sea Culture [1], ancestors of the Inuit and Yupik, felt the fury of the Dena first. Despite the increasing harshness of their lands, the Dena coveted and pushed into them, displacing many of the inland people of that culture. Along the coast, the Old Kechaniya Culture [2] faced a similar intrusion. The Old Kechaniya Culture ended up totally outcompeted by the inlanders with their strong trade links and their reindeer herds and pushed to the fringe, but the Old Ringitani Sea Culture persisted in the North thanks to some ingenuity on their part which a millennia later would have world-changing effects from the future Coast Provinces of Vinland to the Eryuna [3] in North Asia.

This era, the American Migration Period, marked a massive change in the history of the region later called Fusania. Also known as the Early Fusanian Formative, the key elements of later Fusanian society--the Western Agricultural Complex, metalworking, earthworking, sailing, and domestic animals--became established throughout Fusania in an archaeological eyeblink thanks to the dispersion of the Dena. And this Early Fusanian Formative influenced all of Fusania and in time the rest of North America beyond the Divide.

---

Mauno Korhonen, Triumph of the Wolf and Raven: The American Migration Period (1983) (Olastakki University Press)

The Dena migrated from their origin point in far northeast Asia into the Americas as yet another group to live in that region. Along the Yenisei far to the west exists their distant relatives, the Kets and other small-numbered people of Tatary. Through lands later inhabited by a variety of peoples, the Dena crossed the narrow gap between the Old and New Worlds, and emerged along the Hentsuren River.Mauno Korhonen, Triumph of the Wolf and Raven: The American Migration Period (1983) (Olastakki University Press)

It wasn't long before the Dena continued to migrate, displacing many people in the Subarctic thanks to their honed knowledge of local plants. They turned southeast, traveling in the mountains and valleys of Northern Fusania and displacing those who came before them. By around 2,500 years ago, these early Dena migrations were slowing down, meeting organised resistance on the part of other peoples from Northeast Asia as well as established local peoples like those who spoke Wulchomic and Salishan languages [4]. Yet they established many links between these cultures, which later facilitated the Dena expansions of the American Migration Period.

The American Migration Period proper began with the climate changes in Late Antiquity. What caused the Germanic migrations in Europe, what brought down Teotihuacan in Mesoamerica, what caused the chaos in China and the steppes in this era, these same effects caused the American Migration Period. Essentially, the experimentation of the Dena and related cultures such as the Ringitsu, Tsusha, and Khaida in the warmer times of the 1st-4th centuries AD suddenly ran up against the wall of climatic effects. The Dena challenged this head on, intensifying their incipient horticulture and domestication of reindeer, but inevitably began to suffer the unpreventable effects of the climate. This population dispersed far and wide.

In the far north, the Dena absorbed some bands of Inuit, but in turn were absorbed by other bands. Dena practices of land use and tool construction were transmitted to these Inuit, and the most notable effect became the domestication of the muskox, historically attributed to a legendary figure named Kalluk, who perhaps is like the Dena's own "Lord of the Ground". Kalluk himself is likewise attributed to taming the reindeer--oral history attributes him to "stealing" the reindeer from the Dena, who mismanaged the land and its spirits. These stories are backed up by archaeological evidence, which show that by the late 6th century and early 7th century, the pressured Old Ringatani Sea Culture, ancestors of the Inuit, were increasingly adapting to the new circumstances in their homeland. These Inuit would migrate east along the Arctic coast in time. Unlike the Dena, who halted to absorb other Subarctic cultures into their system, the Inuit displaced other "Paleo-Inuit" and would reach Greenland by the end of the 12th century.

South of them, the coastal peoples, mostly those of the Old Kechaniya Culture, were less lucky. They were purely coastal peoples as their inland groups ended up decimated early on. These people, called the Guteikh by the Ringitsu who colonised them in the centuries to come, clung to the coast where they harvested the ocean's bounty, including whales which they processed into food for themselves and tools for nearby peoples. As only the Ringitsu had a whaling culture in the region, the Guteikh thus has a niche to prosper in for the time being. However, in the vast majority of the Nuchi Bay and Yagane Peninsula [5], the Dena displaced the locals to establish the prominent and famous Dena state later called Yahanen, the locals of which would give their ethnonym to far distant people who merely shared the same language family [6].

As the Dena moved southeast along the coast, they met far more established peoples. The rainy and temperate climate was new for the Dena, so they were forced to use their pure numbers to gain a foothold there. The moeity system and most notably the religious idea of the "Sibling Prophets" started here as a fusion of Dena and local influences. Dena people controlled access to reindeer herds which became prestigious, while also becoming powerful elites in these societies, assimilated as they often were. In the Ringitsu, the most affected, the "Wolf" moeity (associated with the Dena) entirely eclipsed the prior "Eagle" moeity except in some marginal Ringitsu-descended groups. Similar influence spread among the Khaida and the Tsusha and Uikara [7], although they mostly kept their older moeity system.

In these coastal peoples, a system of horticulture--which soon spilled over to agriculture--as well as tool designs, earthwork designs, and domestic animals (the reindeer)--proliferated. By the early 7th century, the tehi plant was increasingly domesticated and used for fibers, most notably for summer clothing, ropes, and for sails for their increasingly complex dugout canoes, often formed into a catamaran-style. The increasing population, leading to competition for resources and adaption of the new spiritual beliefs thanks to stress, led to coastal migrations to the south.

In the interior, the Dena merged with and pushed out other Dena peoples, as well as no doubt non-Dena peoples now lost to history. The old "grease trails", traditionally used to trade the key commodity that fish oil was, proved a key migration highway. Cultural similarities led to a relatively easy way to adopt and absorb migrating bands, assuming such an opportunity existed. As such, local Dena peoples more easily kept their culture, despite loanwords from Hentsuren Dena peoples appearing in their languages. Some Dena, however, ended up pushed to the south or to the east, ending up on the Plains or southwards in the American Divides [8], although these Dena remained rooted to the mountains and were only one part of those Dena later called the Apache, who lived south of these early Dena of the Divides.

Everywhere the Dena went they spread their religious outlook, their reindeer pastoralism, and their horticulturalist system based on bistort, sweetvetch, and other simple plants. In the river valleys, the Dena increasingly settled down, finding ample land for food, earthworks, and their herds as well as their ability to import slaves to mine local metal resources. Key among these was the jade found in much of mountainous Northern Fusania. These Dena became cultures of miners, producing valuable jade and later copper for their elite and other peoples.

But in the south, the Dena migrations were once again redirected, absorbed, and halted as they were centuries earlier. The greatest factor is the influence of Wayam [9]. This ancient center, inhabited for countless thousands of years, emerged anew in the time before the American Migration Period. Independently, they emerged a system of irrigation earthworks and the governance thereof to govern their critically important salmon runs which were the finest on the Imaru River.

Contact existed between Wayam and the Tachiri culture, early Ringitsu, and other peoples in this stage of Fusanian history. But Wayam adapted to their innovations very quickly despite their remote location. The Wayamese harvested ample amounts of salmon, and used their slaves to develop increasingly important crops such as species of lilies, camas, biscuitroot, balsamroot, and most importantly, the arrow potato, one of the ancestors of the omodaka [10], while also importing the aquacultural systems of the Ringitsu and their neighbors. While Wayam was just one village at this point, its influence spread amongst both its cultural relatives, the Aihamu people [11], as well as the cultural relatives of nearby villages, the Namaru people [12] and in turn, other nearby groups. The intermarriage, friendly trade, and other factors in relationships between these groups led to the mutual development of all these peoples. However, the sheer number and tenacity of Dena led to plenty of local intermarriage between these groups. With Dena influences came the religious developments of the coast peoples--the Sibling Prophets and their dualism--as well as the adoption of the reindeer as symbol of wealth.

Likewise, the Wulchomic and Salishan peoples resisted the Dena. They adopted earthworks from both them and the Wayamese, as well as the increasingly complex system of horticulturalism found in those groups. Trade and intermarriage with the Wayamese and the Namaru strengthened them, although their leadership ended up becoming dominated by assimilated Dena. Influences from the both the coast and northern interior penetrated their culture, spreading the crops used by the Ringitsu, Khaida, and Tsusha where they were grown to great success. The Wulchomic peoples fell under the influence of the Northwest Fusanians such as the Ringitsu and Khaida, while the Salishans adapted much from the Dena.

Important to these southern cultures was the issue of dealing with local deer, which carried parasites deadly to reindeer. In the religious system brought by the Dena, local deer were considered a dark and evil influence which needed to be balanced out. The local people's practices toward deer hunting dramatically changed in this period as they ruthlessly exterminated deer from their lands. While the issue of parasites--carried by ticks and insects--never abated, destroying deer populations prevented the worst of damage to the critical reindeer herds while also providing a generational boost of food which likewise proved critical to the cultural and sociological development of these Dena influenced peoples.

Despite all of this, the Wayamese and Namaru considered themselves impoverished in reindeer compared to those people of the mountains, termed the "Hillmen". The distinction between Hillmen--those Dena peoples and especially groups strongly influenced by the Dena--and lowlanders was to become a critical factor in Fusanian history. They became fine reindeer breeders, and as the centuries proceeded, breeders of mountain goats and moose, to attempt to circumvent their inherent poverty. Their earthworks developed very early on in order to harnass the maximum amount of plant growth to feed their reindeer as well as their slaves, and were especially crucial for the Wayamese and other Aihamu such as the people of Chemna [13]. Due to the dry, arid climate they lived in thanks to the rainshadow of the coastal mountains, the Wayamese, Chemnese, and other people of the Imaru Plateau became extensively innovative in their development of irrigation and earthworks.

In the furthest south, the Dena encountered their distant relatives, those Dena who lived along the coast, which a millennia later become home to Chinese ports such as Dawending [14]. Likewise, these same Dena encountered peoples from the coast. While these Dena had assimilated into local cultures and had similar traditions, small-scale organisation, and hunting-gathering patterns, the arrival of Dena from the north led to changes in their culture. While reindeer remained little viable in their region due to the disease issue, these Coastal Dena began to group together to form larger social structures as well as incorporate the horticulturalism of the other Dena. Combined with the Maguraku and Waluo [15], Northern Fusanian agricultural practices began to filter into southern Fusania.

Perhaps the most critical development of the Dena was copper working. Dena peoples in the copper-rich areas of the north, such as the Atsuna along the Higini [16], had worked the rich native copper deposits for centuries, and traded them extensively. In the 4th century onward, their exploitation of these deposits became critical, as they traded their tools and ornamentation of copper to Nuklukayet, the Ringitsu, and further beyond. Copper tools became almost as important as fish oil, being used as a symbol of prestige as well as being important for leaders to prove their status.

Such use and demand of native copper combined with the larger population inevitably depleted the best sources of native copper. Yet the Atsuna adapted in time--they first melted the native copper before reforging it, creating superior copper tools. The second adaption likely came from those clans shut out from the copper trade--these clans smelted copper ores to produce tools. They were valued just as highly by other Dena, the Ringitsu, and other peoples, and these copper ore smelting clans became prized partners for marriage as they held the secret to "creating metal from stone". As Atsuna smiths married into Dena clans, ornamental use of copper, and soon silver and gold, expanded throughout Fusania.

The Copper Age dawned on Fusania by 700 AD, and with it many competitive peoples seeking their place in this new world. Some would be assimilated and forgotten to history, yet others became the world-renowned originators of crops and innovations which produced the modern world. Those ambitious Dena with their crests of wolf and raven would never imagine the changes to come soon enough. Although they contented themselves with their dominance of the nobility of many Fusanian cultures, their need to cement their status, be it by their herds of reindeer or their earthworks, and their demand for the increasingly prestigious copper goods produced increasingly complex societies and with it, the opportunity for kings and others to dominate the population.

By land and sea, changes infiltrated Fusania. Locals everywhere soon realised the power of copper, silver, and gold, and what was needed to draw those substances from stone. At the same time, the value of the reindeer became critical in the assessment of the Fusanian elite. Fusanians built earthworks, irrigation networks, and increasingly grand mounds to provide for their cultural needs, while increasing warfare to fuel the new industries of agriculture and mining.

At the heart of this change lay the place named Wayam. This ancient crossroads, a fishing ground at a natural waterfall on the Imaru River turned a trading center, became hugely influential thanks to the ambition of its nobility. Poor in reindeer, yet rich in so much else, the Wayamese Aihamu nobility, influenced by their Dena elite, used the changes brought by the Copper Age to shape Fusania in their own image. As their fellow Aihamu copied them in competition, they set the stage for emergence of classical Fusania under the banner of wolf and raven.

[1] - The Old Ringitani Sea culture (ORSC) is equivalent to the Thule people of IOTL.

[2] - OTL's Kachemak Culture, an Aleut group which lived in Kenai, Kodiak, and other coastal parts of southern Alaska around this period.

[3] - TTL's term for the Lena River in Japanese, from the Tungusic term for it meaning "big river".

[4] - Wulchomic is TTL's term for Coast Salish, derived from the same native root as Lushootseed which means "salt water", referring to the Puget Sound and the Salish Sea ("Whulge"). ITTL, the term "Salish" is reserved for Interior Salish languages, which are very much pushed between the Aihamu people in the south and the Dena in the north, yet still thrive.

[5] - Nuchi Bay is the Cook Inlet of Alaska, the Yagane Peninsula is the Kenai Peninsula

[6] - "Yahanen" means "good land" in Denaina. The Denaina indeed had a very good land compared to other Athabaskan peoples given the geography and climate of that part of Alaska. And ITTL, the term "Dena" indeed derives from our alt-Denaina, who arrived in their land centuries before OTL (thanks to their horticulture and reindeer usage).

[7] - Japanese term for all Northern Wakashan speakers (aside from those who speak Kwak'wala).

[8] - The Rockies

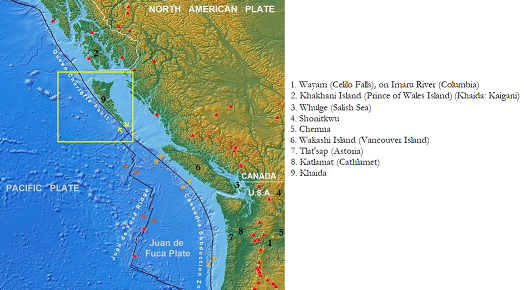

[9] - Celilo Falls, a derivation of its Sahaptin name

[10] - Sagittaria latifolia, aka wapato, a key plant for Pacific Northwest Indians which enabled their sedentary lifestyle OTL along with the reliable salmon runs. Omodaka TTL is Sagittaria fusanensis, an ATL hybrid of S. cuneata and S. latifolia which will be developed in a few centuries.

[11] - Japanese derivation of "Aipakhpam", "People of the Plains", TTL's ethnonym for the Sahaptin people.

[12] - Chinookan peoples, their name TTL derived from the Japanese word for "People of the River" (Columbia River, natively Wimal and Imaru in Japanese).

[13] - Richland, WA, a key site on the Columbia River near where the Snake River and Yakima River flows into it--like Wayam, it was a very important site for local American Indians OTL

[14] - Eureka, CA, a Chinese transcription of the native Athabaskan name for the area

[15] - The Maguraku are the Klamath and Modocs, with this exonym derived from Japanese. The Waluo are the Shasta, their exonym from Chinese. This area is a borderland between Japanese and Chinese influence, a product of post-colonial developments.

[16] - Copper River, a Tlingit loanword meaning "River of Copper". The Atsuna are the Ahtna people.

---

Author's notes

This entry describes a monumental event in the history of the New World, where our horticulturalists/early agriculturalists we've discussed/hinted at spread very far and meet other sedentary cultures, like the PNW cultures (such as the OTL Marpole culture among the Coast Salish). It's the spread of an aggressive pastoralist society meeting various societies which are perhaps at the peak of "hunter-gatherer" societies thanks to the wealth of the land they live in.Author's notes

Originally I intended a narrative piece with the Inuit/Thule (Old Ringitani Sea culture) and their relation with the influx of the Dena to appear here, but I'll hold that off for a bit. The Inuit, Yupik, and Aleuts will feature here, but they're at the periphery of the main focus--an agricultural, pastoralist, and metallurgical cultural area in North America. They'll be important for their relation with various Siberian peoples and in the east beloved figures such as Bjarni Herjolfsson and Leif Eriksson.

Next entry (aside from the little bit with the Inuit/Thule) will deal with Wayam, that place mentioned in this entry--it's crucial to the origin of so many things. Afterwards I'll do an entry on the Western Agricultural Complex (and what it consists of, and its relation to other American agriculture) I keep referring to, discussing local agriculture, the pastoralism of the Dena and others, and horticultural practices. And then we'll do something regarding the coastal peoples--Ringitsu, Khaida, and others--which will be key for South Fusania aka California and its development. After that, we'll come to the start of the Fusanian Copper Age which brings a whole new set of developments and things to discuss.

Last edited:

Chapter 7-Birth of the Ivory Men

-VII-

"Birth of the Ivory Men"

Along the Arctic Ocean, late 6th century

The world seems colder and more violent by the day, Kalluk thought, gazing out onto the endless ice floes in front of him as he recently took to more and more for meditation. His people lost so many promising men to the southerners. He had no choice but to move his extended family far to the northeast, and hope they'd find plenty of reindeer and seals to eventually begin to harvest from the sea. Reindeer, he thought. The animal worshipped by the demons from the south. The southerners called themselves by a variety of names, including something that sounded like "Dena" (according to a young warrior they captured), but to him they were Ingalik, the people with lice [1]. Kalluk remembered an elder saying that encounters with the southerners were once rare, and they formerly went out of their way to avoid meeting real men [2] like his people were, but these days were far too common."Birth of the Ivory Men"

Along the Arctic Ocean, late 6th century

Over the years, the Ingalik pushed further and further into their land, bringing with them their massive herds of reindeer which they seemed to have supernaturally tamed. Where their herds moved every year, the land itself seemed more bountiful, sprouting much sweetvetch, bistort, reindeer lichens, and other plants. Kalluk never knew what supernatural skills the Ingalik possessed which allowed them to enchant the spirits of the land like this, and not even the shamans knew. Although warned to stay away from lands the Ingalik harvested and especially to avoid killing their reindeer, in times of need, Kalluk and his wife were forced to provide for their family. Such needs cost them everything in the end, as he was the sole survivor--sons, daughters, his wife, the Ingalik killed or abducted them all. North and north he went with his extended family, until with his extended family they reached the coast. But the people of the coast mostly rejected them--they claimed the hunting was not good anymore thanks to both the Ingalik and those distant kinsmen fleeing from the Ingalik--so they were forced into the worst locations there.

In the corner of his eye Kalluk saw a dark brown animal--a reindeer. Are the Ingalik near? Or is this one wild? The reindeer darted off as quick as he noticed it, and once again Kalluk's thoughts turned to the Ingalik and their supernatural magic. How did they do it? The plant growth, the Ingalik's selective harvesting of plants, and the abundance of reindeer must be related, not to mention the abundance of life in general. Bears, sheep, and other land animals seemed more common these days. It's as if the Ingalik's magic has bent every spirit in the world to their will.

After an hour of staring at the ocean, Kalluk turned around to head back to his camp and happened upon a small herd of muskox, perhaps ten animals. If only our magic was strong enough to bend the spirits to our will. But why wasn't it? Weren't they already benefitting from this magic by the increased bounty of reindeer and plants? And even trade with the Ingalik seemed more than ever, giving his people more furs and antlers and bones than before. And in return, his people gave the Ingalik fine furs made from muskox. Few real men knew the Ingalik better than inlanders like them--they fought them, traded with them, and were displaced by them. The sack he carried, of some odd fiber the Ingalik supposedly imported from far south, came to him from an Ingalik chief he once killed in the battle that cost him his son [3]. He took the dried food out of the bag, and ate a leisurely lunch. The spiritual value of this place is more than worth the trip, but I will gather something for my kin on my way home.

These thoughts filled his mind as Kalluk returned to his extended family's camp. Thoughts which grew hazy as he wandered, perhaps from exhaustion, perhaps from stress, perhaps from something he ate. The sky turned grey and a cold rain started falling. Thunder struck and he collapsed in the wilderness. Kalluk awoke many hours--or days--later under the Northern Lights at dusk, thirsting and starving. A muskox herd grazed nearby, and not far from him grew a patch of sweetvetch. The herd interested him the most. Furs, meat, and the rarest and warmest of fur, qiviu [4], they give so much to us, yet I wish we didn't have to visit the Ingalik's country to get them.

A spirit spoke back. Those Ingalik kill us and ignore our spirits. But you real men are noticing things. The Ingalik are spiritually powerful and have helped us thrive, but have cut us down at the same time. Strange sights filled Kalluk's vision. They cut us down, Kalluk, indistinguishable shapes in the sky spoke. Our family died, your family died, this is proof the Ingalik do not know how to manage their power. Will you not do something about this for the sake of everything? Steal the power of the Ingalik, and use it to strengthen the world.

Kalluk heard voices, speaking in what he knew were the bizarre tones of the Ingalik. Hazy as everything was, he noticed a group of five Ingalik men wielding sharp spears who likewise noticed the muskox herd. One man led three reindeer behind him. I will not survive this. The Ingalik killed randomly, and he had nothing to offer these men.

"You mean nothing you're willing to part with?" a voice spoke. "Offer them your knife, your cloak, and your sack, and you'll be saved." But Kalluk knew he couldn't offer such priceless goods, that which cost the lives of his family to gain. I've parted with too much. I have nothing more to offer but my life.

"Only your life? You aren't alone, Kalluk," a spirit spoke, which sounded like the voice of his dead family in unison. "Remember that when you offer these men something."

And suddenly everything came to him. The spirits called him here because the land was out of balance. His family, the muskoxen, the reindeer, the plants, the sea, the land, he needed to set things right. And it needed to start with these Ingalik. They must not kill that herd.

Beneath his fur cloak, he drew that treasure he stole from an Ingalik chief--a shining copper knife. Kalluk always felt it was the strongest thing he owned thanks to its spiritual strength. As those men drew closer, he prepared for an ambush attack. I offer the spirits my life, he thought, laying in the tall grass of the meadow.

"And I offer you the wrath of every spirit here!" he screamed, jumping to his feet and impaling the Ingalik man in front of him in the throat. Blood erupted from the man as he collapsed. The four behind him halted, standing shocked and shouting in their language, yet Kalluk charged them and plunged his knife into the throat of the second man near the reindeer, who fled when Kalluk approached. The three survivors rushed him, but Kalluk grabbed the man's spear with his off-hand while plunging his blade into his neck. He narrowly dodged a cut from one Ingalik's spear, blood spurting from his forearm, but repaid the man with his fellow's spear through his gut. The last survivor, shocked at Kalluk's strength and the fall of his comrades, tried to run, but Kalluk tackled him to the ground and wrung his neck.

"You, Ingalik!" he screamed in his delirium. "You must feed the spirits! Pay them back for what you stole!" The man garbled something in his language, and Kalluk tightened his grasp--the man fainted soon after, but Kalluk ended his life with a sharp blow to his skull. Kalluk collapsed, panting from exertion, the impact of the fight slowly hitting him. His bleeding arm pained him.

"You did well," a spirit said. "But this is the start of righting what is wrong. If you thirst and hunger, one of us will feed and nourish you. Our blood, milk, flesh, and fur can save you, and if you pass your knowledge and that of the understanding ones among you, the curse of the Ingalik will be defeated.

Kalluk rose wearily, grabbing a spear from a fallen Ingalik warrior. The muskox continued grazing, seemingly ignorant of him despite what their spirits told him. The strongest of them must live, he suddenly thought, no doubt informed by their spirits. The weak shall nourish us while the strong nourish the land. Turning his attention toward a runt of the muskox herd, he single-mindedly stumbled toward them, and at close range, threw the spear right into the beast. As it emitted a dying shout, the herd gathered together for defense, but Kalluk's shouts and cries intimidated them into abandoning their wounded comrade. The weakened muskox died from repeated spear thrusts, and Kalluk cut chunks of flesh and fur from the fallen beast.

The next morning, a delirious Kalluk wandered back into the camp of those awaiting for him, those who feared he was dead. And Kalluk told them of what happened, and most importantly, what was revealed to him. They recognised Kalluk's experience as deeply spiritual, and began to rever him as a shaman, one who communed with the spirits. And Kalluk's path was clear--adapt to the spiritual change brought by the Ingalik, but preserve the way of life threatened by them. Many rejected him at first, but the coastal peoples soon enough respected his interior people for the amount of muskox furs they brought, along with the trading links they began to establish. Eventually, even the coastal people adapted the muskox, using it to move whale and walrus ivory and other goods to the interior real men, who in turn traded it to the Ingalik. This trade gave the real men a new name they'd be known by the Ingalik and later even more far off groups--the Ivory Men.

Kalluk accelerated the process already occurring--the real men and muskoxen became closer, and soon enough even the reindeer became adapted by the real men as they shifted to a pastoralist lifestyle. This resulted in the Ingalik expansions being halted in the far north, and even pushed back. And he lived several decades more. He became mythologised as a servant of the thunder god amongst the Inuit and Yupik (true to his name "Kalluk"), the demigod who help rule the muskoxen and reindeer. Worship of him even spread to those far northern Dena, descendents of Kalluk's enemies, who themselves later adapted the muskox.

---

The large and stout muskox--not an ox but a distant relative of the sheep family--on average stands about 1.2 meters high and weighs about 300 kg and is among the largest land animals of the High Arctic. The animal produces a thick coat suitable for its Arctic environment, including the inner qiviut down. Muskox usually form small herds, but can sometimes be found as solitary animals. Hunted by humans since Paleolithic times, the muskox slowly vanished from Asia, and would likely vanished from all but the most remote parts of the High Arctic if not for the domestication event traditionally attributed to the Inuit hero Kalluk.

The muskox revolutionised the Old Ringitani Sea culture, and the domestication of the muskox and adaptation to Dena practices of land usage is considered to mark the transition point between the Old Ringitani Sea culture and the Thule culture, conventionally dated around 650 AD. The Thule now had an extremely hardy pack animal, one capable of surviving where the larger reindeer preferred by the Dena had trouble surviving. The muskox produced a quantity of milk sufficient for nursing infants as well as the small number of lactose tolerant adults, improving nutrition. And like how the reindeer's ability as a pack animal to move large quantities of goods changed Dena material culture, the muskox did the same for the Thule, albeit it was not quite as sturdy of a pack animal and carried much less of a percent of its body weight. The Thule adapted new means of storing and transporting food.

The end result was a population explosion amongst the Thule people. More children surviving meant more fighting men and childbearing mothers for the next generation. These Thule heard lurid tales of Kalluk's story, now often told in a way which placed him as the turning point of the world. By sacrificing those five Ingalik warriors, he started the process of the rejuvenation of the world, weakening the powerful magic of the Ingalik. In return, Kalluk and his descendents and his allies gained control over the muskoxen, thankful to be free from their thralldom to the Ingalik. Hearing this tale, the Thule became more fierce than ever in repelling Ingalik bands from their territory.

Although they reclaimed much of their lost land and hunting grounds, like many pastoralist populations, the Thule constantly required more land. The Dena of the interior possessed equal technology, but lived in larger groups, and could call upon a much larger and developed trade network permitting access to worked copper, superior wood products, and goods made of tehi fiber. The Thule lived in a land without those goods. Thus, the Thule advanced along the path of least resistance, east and south along the Arctic Coast and across the sea into Far Northeast Asia and the Arctic Archipelago. There, they displaced local bands of Kinngait culture [5] in the east and other proto-Thule bands in the south and west, and made some inroads against the Chacchou [6], also a reindeer herding people.

Despite their land being bitter cold and extremely harsh, the Thule nonetheless eeked out a living in this environment, one better than before, thanks to their adoption of the muskox and adaption to many Dena practices. Known as the "People of Ivory" and sometimes the "People of the Warmest Fur" to their neighbours and especially distant peoples, the Thule became more integrated into regional trading networks. In return for finished copper tools, wooden crafts, and tehi products, the Inuit gave soapstone, muskox pelts, as well as whale ivory. As their remote location limited the volume of goods moved between various locations, the demand for each side's rare goods remained very high.

Amongst more southern people like the Ringitsu and Khaida, Thule goods were extremely rare--a saying went that to obtain a cloak of muskox fur, one sold their wife to the Gunana, but obtained a new wife upon the return home. They perceived the Dena as greedy and unreliable to deal with. As Dena bands further from the Ringitsu and Khaida--and closer to the fabled Ivory Men--offered more reasonable terms for these goods, and increasingly long-distance trade started. To process more goods for this trade, the peoples of the northern coast needed more land--and slaves. Not only would voyages along the north coast accelerate by the start of the Fusanian Copper Age in 700 AD, but so would voyages to the south, voyages which would continue the reshaping of the southern lands already well under way.

[1] - An unkind exonym for Athabaskans used by the Yupik OTL--at this point, Yupik and other Inuit languages have not separated so I will use it here

[2] - Literal meaning of the names of several Inuit groups like the Yupik, Iñupiat, etc.

[3] - Kalluk has a tehi sack, made of Apocynum cannibinum, Indian hemp. It is prized amongst the more northern Dena who have no access to the plant (as it is traded from the Ringitsu), and thus very rare for an Inuit man to own.

[4] - Alaskan dialectual form of qiviut, muskox down, which will have several different names from non-Inuit cultures who encounter it

[5] - Dorset Culture, named for the Inuit name of Cape Dorset "Kinngait"

[6] - Chukchi people, a Japanese rendering of their exonym meaning "rich in reindeer".

---

Author's notes

Since we're focusing on this part of the world, we obviously needed to mention the Thule/Inuit. Unlike the Thule of a certain other timeline which I had to stop myself from making random references to when writing this, these Thule are a more fringe and marginal people and won't be turning the Arctic and Subarctic into their playground anytime soon. That said, they're obviously on a slightly different path than OTL which will have some interesting results for everyone involved both now and soon to come.Author's notes

As I mentioned in the previous entry, the next entry will deal with the northern (well, central) parts of Fusania along the Columbia River and its development of complex civilisation, and then we'll cover this Western Agricultural Complex in a bit more detail.

Thoughts and comments on this and previous entries is always much appreciated.

Last edited:

Yes (basically every culture here will have elements of human sacrifice, like their OTL equivalents tended to), it's more along the lines of "we need to kill strong people to maintain the vitality of local spirits", which can be done through killing people in combat or capturing and sacrificing them. But the population density and thus manpower of the area is and will be so low (even many centuries after this event) that it's unlikely they'd ever be able to have epic flower wars and such. In general, they'd likely be content with sacrificing a strong slave (either purchased or captured) or muskox/reindeer, the latter of which will spur plenty of conflict among fellow Inuit as well as neighboring Dena (religious needs can be flexible, especially in a society like this). So it's more likely in a typical conflict they set out to steal a neighboring group's reindeer or muskox and as a nice bonus capture a few people to sacrifice or kill some strong warriors in combat.Do the Thule adopt human sacrifice a la the Mesoamericans?

I will post an update regarding Wayam (and its cultural relatives) tomorrow morning. For previous comments I neglected to reply to:

And not just Asian geopolitics, since if we consider the OTL 16th century in East Asia, we have the start of European influence in the area. The term "original world war" is often given to the Seven Years War, although some historians label previous conflicts like the War of Spanish Succession or the Eighty Years War as such, but the first time I saw the term "true first world war" applied was in regards to the Seven Years War, so we'll go with that. TTL it's highly likely that a comparable event to the Eighty Years War or other contemporary conflicts may be the one usually labeled as the "true first world war", "world war 0", etc. As for what that means for Amerindians, OTL has nice examples of conflicts between British allied Indians and French allied Indians.

But this timeline is subtitled the "Shaping of Fusania and Beyond". "Beyond" has quite an implication, and odds are some peasant dirt farmers in OTL Oregon aren't as interesting as the peasants of Mesoamerica or the Andes for certain groups of people.

Thank you, there are lots of stories to be told here. Unfortunately, it will be quite a while before we even get to the part where the Japanese and indigenous Fusanians meet, but the dialogues between the curious monk Jikken and the elderly Fusanian exile Gaiyuchul will fill in a nice frame story when it needs to be there.You have my attention, metalinvader. I’m intrigued by the premise of Japanese contact with North America and I enjoy how this reads. Keep it up!

Japan and China is basically England and France (or given the population and economic disparity, England and the Franco-Spanish Union) after all, with Korea thrown in as a mix of Scotland and the Low Countries. How much of that comparison will hold true TTL we'll see, but I can promise that TTL's East Asians would be confused at OTL's relative lack of Sino-Japanese wars.I know it's probably a no brainer, but a less isolationist Japan will have a big impact in asian geopolitics.

And not just Asian geopolitics, since if we consider the OTL 16th century in East Asia, we have the start of European influence in the area. The term "original world war" is often given to the Seven Years War, although some historians label previous conflicts like the War of Spanish Succession or the Eighty Years War as such, but the first time I saw the term "true first world war" applied was in regards to the Seven Years War, so we'll go with that. TTL it's highly likely that a comparable event to the Eighty Years War or other contemporary conflicts may be the one usually labeled as the "true first world war", "world war 0", etc. As for what that means for Amerindians, OTL has nice examples of conflicts between British allied Indians and French allied Indians.

But this timeline is subtitled the "Shaping of Fusania and Beyond". "Beyond" has quite an implication, and odds are some peasant dirt farmers in OTL Oregon aren't as interesting as the peasants of Mesoamerica or the Andes for certain groups of people.

This timeline is really interesting. So, has Mesoamerica had any form of trade/contact with Fusanian cultures yet or is that happening later?

Also as someone who lives in the pacific northwest I'm really wondering how the indigenous nations of the Puget Sound will develop differently, as well as how places like the Hoh Rainforest will be differently seen ITTL.

Also as someone who lives in the pacific northwest I'm really wondering how the indigenous nations of the Puget Sound will develop differently, as well as how places like the Hoh Rainforest will be differently seen ITTL.

Last edited:

Chapter 8-To Tame a River and a Desert

-VIII-

"To Tame a River and a Desert"

Tall, forested mountains mark the boundary between the rainy, wet coast of the Pacific Ocean and the interior Imaru Plateau [1]. These mountains are volcanoes, some of which are still active, formed by a mantle plume hotspot of the same sort which created Hawaii. The greatest eruptions of these volcanoes occurred long before human times--17 million to 6 million years ago, this hotspot erupted continually and poured out vast quantities of lava to create the modern Imaru Plateau and the modern Imaru River. The mountains blocked the moist air from reaching the Plateau, yet the soil of this region was deep and very rich. One river, the Imaru River, punched through these coastal mountains to reach the Pacific Ocean, creating a gap for animals to easily pass between the Plateau and the coastal regions."To Tame a River and a Desert"

Catastrophic events like these eruptions shaped this land--and its people. Millions of years later, massive floods from melting glaciers at the end of the last ice age swept over this landscape and down the Imaru River. The first humans to live in these lands witnessed these floods, which passed into the legends of their distant descendents. Similarly, the intense volcanic eruptions of later times likewise passed into local legends, where the volcanoes were transformed gods and home to powerful thunderbirds, who controlled their eruptions.

Not long after the great outburst floods, the first sign of humans in the area appears at the site of what would become the first--and for a time, greatest--city west of the Rockies. The intense geologic history of the region created a waterfall, which became the perfect place to gather salmon, which formed the main part of their diet. All sorts of water plants and animals likewise lived at this site, which later people called "Wayam"--"echo of falling water".

Thousands of years later, as the Roman Empire reached its golden age, the people of Teotihuacan finished the Pyramid of the Sun, and the Lord of the Ground tamed the reindeer amongst the Dena, two groups of people lived permanently in this rich land--a group of Aihamu as well as the easternmost Namaru. Over a dozen other groups, including those from hundreds of miles away, regularly gathered at the site during the salmon runs, or periodically during other parts of the year to trade. At times, up to ten thousand people congregated here during particularly good years. All sorts of goods (including people) and ideas exchanged hands at Wayam, a borderland between east and west.

The nearest village to the Wayam Falls itself shared its name with the falls and was an important village of the local Aihamu people, who called themselves the Wayampam [2] but are often known in history as the Wayamese. Many people from far beyond passed through this village to gather the rich salmon runs of the area. The Wayamese and their close neighbours likewise frequently gathered in this place to hold ceremonies related to the changing of seasons to pray for prosperity.

Along the Imaru Plateau, drought could strike in any year, and potentially for decades or more, much reducing the flow of the Imaru and constricting plant and animal life on land. Those who lived there knew of the fickle nature of the climate, but had little means of counteracting the damage. The end of the 3rd century saw one of these lengthy droughts. For nearly 40 years, less rain fell than before and the Imaru ran at a reduced flow, with only a few wet years to break up the pattern.

In this time of poverty came the beginnings of change. From the north came bands of Dena who brought with them bits of the culture and lifestyle changes occuring far to the northwest via their intermediaries, the Chiyatsuru, who became increasingly Dena-ized. This included their semi-domesticated plants--sweetvetch, bistort, and others--and most importantly, their pack reindeer which fed upon them. The sight of tame reindeer, normally a rarity seen only in the north along with the mountains, must have filled the Wayamese and other Aihamu with shock. It is likely that in the first years, right at the end of the 3rd century, many reindeer were bought and sold at Wayam, as the Chiyatsuru integrated their Dena allies to the new system.

But keeping reindeer was challenging in the lowlands, for this was deer country. White-tailed deer often carry brainworms, a parasitic nematode which while mostly harmless to the deer, are usually fatal to reindeer and moose. The Dena and Chiyatsuru noticed this, and quickly attributed it to the spirits of the deer in the area. Refusing to abandon their herds, they embarked on campaigns of extermination against deer with an unusual vigor. For the time, the Dena grazed their animals in the highlands in the summer, and moved to the lowlands in the winter.

This extermination campaign against a major game animal did not endear the Dena and Chiyatsuru to the Aihamu, who fought back against the people decimating their key source of food. But like many clashes against the early Dena and Dena-ized people, the battles went poorly. The better nutrition, larger numbers, and superior logistics of the Dena and Dena-ized cultures held the clear advantage. However, the Wayamese had their own tool to fighting back--their vast network of alliances, forged by many decades of successful trade. They used this to call upon other peoples of the Plateau as well as some from downriver like the Namaru to protect their lifestyle.

Despite many victories over the years, they alliance fell to infighting amongst themselves in addition to the death of many warriors. The slaughtered deer often became food and tools for the Dena and allies, resources now denied to the Aihamu and Plateau people. And the drought continued mostly unabated, further decreasing the deer population. Faced with these clear signs (perhaps interpreted religiously), and faced with the desire of many more peaceful Aihamu and Namaru to maintain peace to continue trade, the people of the Plateau effectively fell in line with cultural Dena-ization as a new nobility of reindeer herders dominated their people. The white-tailed deer, and to a lesser extent the mule deer, were overhunted to local extinctions in much of the region.

Critically, the Dena demanded water from the river to grow more fodder for their reindeer. Unlike more northern Dena or the Ringitsu, these pre-Migration Period Dena did not understand the methods of making earthworks, with the large villages of Tachiri culture Dena along the Hentsuren only a distant legend. This forced the Wayamese to independently innovated similar techniques. Such building of additional channels along the river went along well local fishing, while also producing additional land for reindeer fodder.

The additional challenge of growing these subarctic plants in the warmer lowlands of the Imaru Plateau led directly to the domestication of local plants in the centuries to come. Camas (Camassia) and biscuitroot (Lomatium) were likely the earliest local plants to be gardened in this manner, as the Wayamese created channels and other primitive irrigation techniques to ensure their growth and easy reliability. Soon after came nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) and amaranth (Amaranthus), both exceptionally useful plants for feeding both reindeer and humans alike. As the decades passed, they supplemented this by increasingly directing the growth of tule (Schoenoplectus acutus), a water sedge, in their wetlands. This helpful plant was preferred to make baskets, clothing, roofing for lodges, fish weirs, and also had parts which could be eaten or fed to reindeer. With water plants came the increasing use of arrow potato (Sagittaria latifolia), pond lily (Nuphar polysepala), and tiger lily (Lilium columbianum). While other groups in the area conducted similar experiments with these local plants to feed their reindeer, Wayam served as a natural place for ideas, plants, and other products of success to be exchanged. Thus, whether it was the Aihamu, the Namaru, the Furasattsu [4], the Chiyatsuru, or another group who first started the experiments or grew the most superior plant didn't matter--the other groups would adopt it by way of the Wayamese sooner or later.

This regional complex became known as the Irikyaku culture, after the town of Irikyaku (called Itlkilak in pre-colonial times) [5] where the first artifacts were found. Irikyaku artifacts typically include nearly uniform designs for tools made from reindeer antlers and bones, a few similar styles of pottery designs, and early evidence of artificial channel and pond building, with the main regional differences being those to the east or west of the mountains. Most critically, the Irikyaku culture eliminated the distinction between summer and winter villages and established a pattern of sedentary villages for all but those in the high mountains. The Irikyaku co-existed with the Late Chishinamu culture [6] of the Furasattsu. Their artifacts and designs retain similarity for over 300 miles in a radius centered around Wayam, evidence of a massive regional shift in culture, technology, and way of life starting around 350 AD and reaching its full extent by 400 AD.

The artificial channels, especially in drier areas, proved the perfect place to encourage these early experiments at agriculture. The intensive labor needed to construct these channels led to the early Wayamese to demand the most from them. The Wayamese transplanted promising-looking plants from the wild or from already built channels to grow along new channels, and picked out the weaker and lesser plants while preserving the larger ones, usually to move to new channels. The Wayamese removed plants they didn't prefer from the area entirely, and never transplanted them.

Channel-building was very labour-intensive. They were directed by medicine men who mediated with spirits called takh [7] to place energy in the plants, energy which would later flow back into humans and animals to ensure good health. The medicine men needed to fight off evil takh which poisoned the beneficial takh and caused disease of plants, animals, and humans. The Wayamese conducted channel-building in winter, when the reindeer herdsmen pastured their herds in the lowlands and had their reindeer available to assist in hauling dirt and mud. Slaves provided most of the manpower in constructing these channels.

All of this led to the increasing stratification of society in the region by the 6th century for all but the most isolated hill tribes and desert dwellers. At the top of society sat the nobility, the keepers of reindeer, who migrated from the mountains in summer to the lowlands in winter. As bone and horn remained the most important materials for making tools (including fishing spears and digging sticks), and they held access to the best groves of trees (used for other tools and the increasingly complex weirs), the reindeer herdsmen effectively were the wealthiest people and thus had ample opportunity to acquire and distribute tools to other members of society. Elements of coastal-style potlatches arrived in Wayam during the Irikyaku, as well as the construction of coastal-style longhouses which were used by the elite (and their extended families and slaves) as palaces but not used by lower-status individuals, likely due to the expense in moving the large amount of wood to construct these longhouses. Below them were the common people, who lived relatively freely yet did not own reindeer or have access to the pasturing grounds. They could move up in status by acquisition of wealth, of which the quickest method was by success in warfare against the Amorera or other hillmen [8]. At the bottom were slaves, people whose roots and ancestry had been stripped from them. Slaves were traded from as far south as the Central Valley of Zingok [9], captured in battles and raids. The desperate poor could sell themselves or their children into slavery, providing another source of slaves. Wealthier commoners might own some slaves, but the majority were owned by the nobility. Slaves could be freed, in which case they'd become commoners. Outside this entire system lay the medicine men, who could be from any class. To become a medicine man was a mixture of luck and choice, and relied on one seeing visions of spirits. Initiation rites were trying and harsh, but to become a medicine man granted one great influence in society, as only they could manipulate the takh and keep people, animals, and the entire land healthy.

The Irikyaku reached their terminal phase in the late 6th century. Wayam had absorbed neighbouring villages on both sides of the Imaru to become a thriving proto-city of almost 2,000 people. The Wayamese constructed large marshes and channels to increase the harvest of fish and water plants as well as to irrigate fields of camas, nutsedge, and other land crops. This fed both the locals as well as visiting peoples who traded goods from all around the entire region. This cultural complex extended to other key sites along the Imaru like Chemna [10]--in later centuries the greatest rival of Wayam--or Shonitkwu [11], the Chiyatsuru equivalent of Wayam. In this phase, Chemna and Shontikwu had over a thousand permanent residents each, with many minor villages have several dozens of permanent inhabitants.

At the end of the 6th century and continuing to the 7th century, a major drought occurred, resulting in the solidification of these traditions. Most importantly, this period marked that of the American Migration Period and the arrival of a very different group of Dena. These Dena bore new breeds of reindeer, new breeds of plants, and most importantly, the arrival of a new cultural outlook and its influence on the life of the people influenced by the Irikyaku culture. This great change is why the Irikyaku fades into several other cultures by the year 600.

The American Migration Period introduced the culture of later Dena as well as that of coastal people to the Aihamu. These Dena warred with the ruling class of the Aihamu, assimilating and displacing them. They transplanted elements of their social system to the Aihamu and other people of the plateau, including the moeities of Wolf and Raven, elements of a clan structure, and belief in the Sibling Prophets with its dualistic division of the world. As trade networks reconstructed, the Aihamu spread these cultural beliefs throughout the region.

Sometime around the year 750, the Copper Age reached Wayam, as the Wayamese began importing smelted copper from the north, marking the beginning of the Imaru Copper culture. Because of the rarity of worked copper tools, and even moreso, the rarity of arsenical bronze, these tools became yet another elite status symbol. Like with their reindeer, the elites of Wayam loaned out these tools to others in society, especially for the further construction of channels, cementing themselves as the leaders of society. Metal tools made the work of digging channels and constructing artificial wetlands easier.

The population of Wayam, Chemna, Shonitkwu, and other important centers continued to grow at an accelerated pace, increasing the demand for more earthworks, the slaves to build them, and the raiding expeditions to acquire slaves. During drought years, the Aihamu and other people of the plateau put increasing strain on the river, threatening the food supply, water supply, and especially the valued fishing grounds. All of this meant a demand for solid leadership which the collective leadership of the nobility was not providing. It would be in these cities around the year 800 when the first emergence of true monarchs appears.

[1] - Columbia Plateau

[2] - "-pam" (and cognates), meaning "people" is a typical ending in Sahaptin for tribal/ethnic groups, hence "Wayampam" ("people of Wayam"), "Aipakhpam" ("people of the plains"), etc. It should also be noted that sitting on the easiest path across the Cascades, Wayam is a borderland, and that like OTL with Sahaptins (Tenino) and Chinookans (Wasco-Wishram), the Wayamese mix freely with neighboring bands of Namaru, facilitating a lot of cultural exchange.

[3] - Generic Japanese exonym for Interior Salish peoples, deriving from a Chinookan (TTL Namaru) exonym for a few nearby Interior Salish bands

[4] - Generic Japanese exonym for Coast Salish peoples, derived from a Nuuchahnulth (TTL Attsu) exonym meaning "outside people".

[5] - White Salmon, WA

[6] - Late Marpole culture, a Coast Salish archaeological culture named for Marpole (part of Vancouver, BC), TTL having a Japanese derivation for its Coast Salish name. The Marpole culture OTL marked the origin of sedentary society amongst the Salish and beginnings of the complex culture encountered by 18th century Europeans.

[7] - An extrapolation/alternate evolution of certain OTL Sahaptin animistic beliefs regarding guardian spirits and their role in nature.

[8] - Japanese exonym for the Molala, deriving from a Kalapuya exonym. "Hillmen" in general is a term used for groups which don't extensively use earthworks (typically because they live in the hills or mountains), but eventually comes to mean "barbarian" (thus why it's a term used for desert cultures). As the Amorera are pushed into the mountains, they retain more egalitarian social structures but develop a raiding culture.

[9] - Westernised form of "Jinguo" (金國), "golden country".

[10] - Richland, WA, near the Priest Rapids, another key fishing site of the Sahaptins

[11] - Kettle Falls, WA, a major waterfall on the Columbia River similar to the Priest Rapids or Celilo Falls which was a major fishing site of the local Interior Salish.

---

Author's notes

Here is our first look at some groups outside of the far northwest corner of the coast, and they'll be quite an important group for the rest of this TL. Basically it's where "civilization" in the literal sense (people living in cities, not just glorified villages) begins. There's probably more I can expound on regarding something so critical, and I probably will when I do a post on the Western Agricultural Complex and just how/why a major lifestyle change emerged in the past few centuries.Author's notes

I forgot to include this section at first because I was a bit rushed for personal time when I was editing this chapter for posting here.

Last edited:

This timeline is really interesting. So, has Mesoamerica had any form of trade/contact with Fusanian cultures yet or is that happening later?

That'll be a bit down the road, as sailing has only recently been invented and is still uncommon even in the northwest with the Ringitsu and others (since a dugout canoe is cheaper--tehi sailcloth is very expensive and sailing vessels need more trees--and gets the job done almost as well). But regional trade is increasing and some of those coastal peoples are part of the groups moving around in the American Migration Period (by both land and sea). They've gotten pretty far already and are spreading their innovations as they go, but it's a ways off before they'll be able to sail to Mesoamerica with any regularity. Right now there's just no reason to keep sailing south--the further south you get the less the locals have to offer.

Quite differently indeed. At the start of the Copper Age (8th century) they're already on a much different path than OTL, and especially for the people of the *Hoh Rainforest given their more exposed location, are having many encounters with the coastal peoples from further north, some peaceful, some not so peaceful.Also as someone who lives in the pacific northwest I'm really wondering how the indigenous nations of the Puget Sound will develop differently, as well as how places like the Hoh Rainforest will be differently seen ITTL.

Chapter 9-Fruits From Earth and Water

-IX-

"Fruits From Earth and Water"

J.E. Haugen and Seppo Savolainen, Fusania's Harvest: An Encyclopedia of the Western Agricultural Complex (Ilonlinna [Charlottetown, PEI] University, Vinland) 1980

"Fruits From Earth and Water"

J.E. Haugen and Seppo Savolainen, Fusania's Harvest: An Encyclopedia of the Western Agricultural Complex (Ilonlinna [Charlottetown, PEI] University, Vinland) 1980

The Western Agricultural Complex (WAC), sometimes called the Fusanian Agricultural Complex, is the term given to an independent center of plant domestication in Western North America. Its origins date to the beginnings of pastoralism and accompanying increase in horticultural practices in the far north of Fusania around the 2nd century AD, with the center of plant domestication along the northwest coast from the mouth of the Imaru to Old Ringitania, and it reaches its final periods of experimentation around 1200. The Western Agricultural Complex was the last center of independent plant domestication to originate, with some of its associated plants showing little distinction from wild forms. Domesticated animals and a complex agroforestry system were extremely important to the success of the WAC, enabling extra sources of protein and calories as well as providing tools, manure, fuel, shade, and windbreaks which enabled the system to work. These plants and animals became critical to not only indigenous Fusanians, but numerous other indigenous Northern Americans, and eventually people around the globe. In some writings, it is called the Fusanian Agricultural Revolution, but this term is disputed by some anthropologists, archaeologists, and historians who consider it an evolution (not a revolution) from proto-agricultural practices to horticulturalism to full agriculture.

Some of the Western Agricultural Complex's crops have become key staples for both humans and animals alike globally, such as omodaka (sometimes called river potato) (Sagittaria fusanensis), river turnip (Sagittaria cuneata), sweetvetch, common bistort (Bistorta vulgata), and the Fusanian lupine (Lupinus fusanensis), or of major commercial importance like tehi (Apocynum cannabinum). Others like camas (Camassia esculenta), rice lily (Fritillaria camschatcensis) and biscuitroot (Lomatium) are important local staples in some parts of the world, especially in Fusania, elsewhere in the Americas, or in the Far East. Some WAC plants are nearly extinct, having faded back into their wild forms or are only grown in isolated parts of Fusania.

---

Practices of the Western Agricultural Complex

Fusanian agriculture had a number of diverse and unique practices which are related to its origins and its social status. In Fusania, agriculture was an extremely low status activity which existed as a supplement to the preferred hunting and fishing techniques which had been practiced for thousands of years. Unlike in other parts of the world, where agriculture led to people settling down, indigenous Fusanians already lived in sizable villages of a few hundred people before they ever began any sort of true agricultural practices. This was due to the wealth of the land in terms of wild plants, animals to be hunted, and especially fish. The Western Agricultural Complex emerged as an evolution of horticulture, which was practiced due to the need to feed the herds of reindeer which became the most high status animal.Practices of the Western Agricultural Complex

Key among these were the ubiquitous earthworks and waterworks, which ensured Fusanian agriculture would become focused on water plants. These appear to be a cultural legacy of the Dena people of the Early Tachiri culture and those later cultures influenced from it, who used these earthworks at their villages as a means of prestige, but also as a means of flood control, water management, fishing tools, and encouraging the growth of certain plants, most notably those of genus Sagittaria. The two most important independent developments of this are at Nuklukayet on the Hentsuren and Wayam on the Imaru, created by two very different groups of Dena, each of which emerged by the 4th century. These earthworks and waterworks diffuse over the following centuries even before the start of the American Migration Period, reaching inland to the Continental Divide and as far south as Tappatsu [1] near the modern border of Zingok. Thus, by the start of the 7th century, much of Fusania already practiced a form of horticulture which in the key places of plant domestication--the Imaru Plateau and far northwest [2]--was spilling over to agriculture.

The addition of the Sibling Prophets to Fusanian religious beliefs during the early American Migration Period resulted in revolutionary changes to agriculture in time. Carried by the later Dena migrations and the early coastal migrations from the far northwest and expressed in many ways contigent on the culture influenced, plants became categorised based on their relation to the resonance of the universe, symbolised by "dark" and "light". Practically, this meant finding dualistic dichotomies in these plants, for instance, the distinction between plants which grew in water versus those which grew on land, and those whose edible parts were below the ground versus those above ground. The most cited example in the literature is how readily 15th century Fusanian traders noticed the potato in its earliest moments in Mesoamerica as the spiritual counterpart of the omodaka, and imported it into their own lands, but similar distinctions were noticed for many centuries. Their effect on the body was also studied by these early farmers, who used this to sort plants into various categories.

These practices were intensely spiritual, and the domain of the medicine men and shamans. Indigenous Fusanians believed medicine men needed to talk with the spirits in order to ensure the plants would be nutritious and able to sustain them. In some cultures, like on the Imaru Plateau, the medicine men placed spirits called takh into the growing plants to ensure they could pass on their energy to humans and animals. These plant-focused medicine men and shamans became an important subclass of the religious castes who eventually accrued more and more power by the Fusanian Copper Age to form the ruling caste over the nobility, from where the traditional princes of later Fusanian city states arise as the first appearance of state society and monarchy in the region.

Under the guide of their shamans and medicine men, the Fusanians thus sowed their fields and bogs with the plants they relied upon. The more intensive earthworks and waterworks were demanded from the native nobility to compete with other noblemen. The end result was an agriculture which covered all bases--nutrition, vitamins, animal feed--and a population set up to farm it.

These beliefs led to the Fusanian version of the two-field system by the 8th century AD. Half of the field would be flooded and grow water plants, and half of the field would grow dry-land crops--typically this would be an alternation between omodaka and camas. The influx of nutrients from the flooding of the field helped enrich the field for the following season. In some parts of Fusania, a three-field rotation quickly followed this development, where one field either lay fallow (and flooded) or grew a non-food crop (typically lupine or tehi). This occurred as an evolution of religious beliefs, where water and land crops constituted two fields each, and the fallow (or flooded) field constituted the "pillar of harmony", symbolising the initial state of the universe.

Use of controlled burning--a tradition tens of thousands of years old in the region--remained common in the Fusanian agricultural system. Traditionally used to encourage the growth of favored plants or smoke out game, in the early agricultural period it was used to enhance the fertility of the land by burning the forest. Fusanian slash-and-burn agriculture tended to be rather light compared to other cultures. It usually occurred only every few years, and under strictly controlled conditions so as to minimize the loss of important plants like reindeer lichen and to maximize the availability of useful trees like oaks, bigleaf maple, and cedar yet also ensure significant new growths of birches and other trees and plants which colonized burned forests. Although already a complex system by the early Copper Age, this forest management system paled in comparison to the complexity of Fusanian silviculture found in later centuries.

In some places--namely the stony, barren coasts of the area--soil management was crucial for this process. Notably, the Ringitsu among other far northwest peoples developed a means of permitting agriculture in these barren areas. Dirt from the interior mountains was mixed with sand from the beach, ashes, seaweed, living and dead fish and other beach life, and small animals both living and dead to form new soil and form the base for earthworks. Spiritually, this practice originated as creating local harmony--making life from barren rocks--by melding together elements of the land and the sea as well as the inferior "beach food" which made men weak and superior hunted game which kept men strong, the land was restored to a harmonious state. Creation of these plots boosted the productivity of marginal coastal lands and enabled a full transition to agricultural even in northerly Ringitania by the early Copper Age. This practice would spread throughout Fusania by the 11th century thanks to the American Migration Period.

The tools of Fusanian agriculture into the Copper Age remained comparable to those of previous eras. The digging stick, a tool of wood and antler, was the most common means of harvesting crops. Tools of wood, bone, stone, and antler in general were used to prepare fields for sowing and harvesting. The earthworks were constructed by hand, using primitive versions of shovels, reed baskets, and reindeer and dog power to move dirt and water. Because of the need for antlers and bone, the nobility who controlled the main source--reindeer antlers and bone--retained a great deal of power as through potlatches they distributed these materials to their followers.

By the 9th century, things were changing all throughout Fusania. The proliferation of smelted copper, silver, and gold spread throughout the entire region through the trading networks of the Dena and others. The sheen and hardness of these new metals immediately attracted the attention of the nobility, who endeavoured to equip their commoner followers and slaves with tools made of these metals. The most prestigious leaders equipped their followers and slaves with tools made of tumbaga (archaelogically named for this fusion of copper/silver/gold's similarity to the common Mesoamerican alloy of the same name) or other alloys of copper with bronze and/or silver. These tools were regarded as superior to all other tools, and most suitable for performing ritual ceremonies regarding the first fruits from the earth.

Arsenical bronze--exceptionally strong copper created thanks to its impurities--likewise was an important metal for constructing agricultural tools, but there was no concept of smelting arsenical bronze in the early Fusanian Copper Age, and instead, arsenical bronze was regarded as a powerful metal thanks to its smiths literally pouring their souls into it. The arsenic in the ore poisoned these smiths and led to their crippling as well as their early deaths, but this was regarded in religion as an example of universal balance--by using the fire Raven stole from the gods to destroy the rocks (by melting) the gods created, these smiths tended far too much toward the "light" aspect of the world. To balance things out, their crippling and often painful death allowed the "dark" aspect of the world to shine through in their craft, leading to "balance" in the tools they made, and thus those tools' spiritual power. The lesser nobility provided their slaves and followers with copper tools as a matter of prestige.

Regardless of the methods of their construction, indigenous Fusanians of the 6th-9th centuries accelerated their construction of ponds for aquatic plants and fish harvesting. Methods for shellfish gardens, common along the coast from the Whulchomish in the south to the Ringitsu in the north, proliferated, and helped inspire gardens for aquatic plants and other forms of aquaculture and agriculture. By the 9th century, this emphasis on wetlands would lead to the domestication of the local species of mallard as the Fusanian duck, an important domesticate of the Fusanians.

---

Key crops of the Western Agricultural Complex

Key crops of the Western Agricultural Complex

Omodaka (Sagittaria fusanensis)

Omodaka, sometimes called river potato, is the most critical staple crop of the Western Agricultural Complex, occupying a position akin to maize in Mesoamerica or rice in Asia. The plant is a hybrid of Sagittaria cuneata, the river turnip, and Sagitarria longifolia, the arrow potato, and grows to a larger size than either. It is somewhat more drought tolerant than its wild ancestors, but still requires damp, marshy ground to grow in. Domesticated omodaka is intolerant to severe cold, unlike S. cuneata, with its northernmost range in coastal Ringitania. Omodaka is tolerant of many different water conditions, and can cleanse polluted waterways--as such, it was usually grown near sewers and latrines, amongst other places.

Historically, its ancestors were utilised for thousands of years as a good starch and supplement to the protein rich diet they ate. Omodaka was functionally very similar in this regard, but was an even greater source of calories and carbohydrates. Cooking the omodaka in Fusania was traditionally done in an earth oven until the early 2nd millennium. Digging sticks made of wood, antler, and bone were the main means of removing the omodaka tubers, but these sticks became increasingly complex and by around 1000 AD, the foot plow became common in Fusania.

Omodaka displaced its wild ancestors in most places it grew in, barring the colder interior and far north. S. longifolia in particular fell out of favor, but was still gathered by some groups of hillmen as well as in times of famine, in addition to becoming grown for the medicinal value of its leaves.