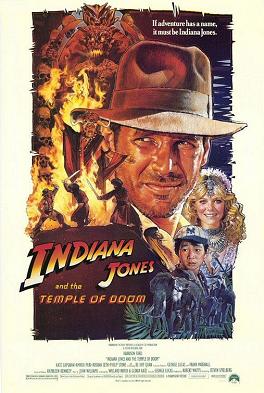

Mask of the Monkey King: An Indiana Jones Adventure (1984)

Mask of the Monkey King, subtitled “An Indiana Jones Adventure”, is the second installment in the Indiana Jones saga produced by Amblin Entertainment in partnership with Lucasfilm. The film follows on from the events in

Raiders of the Lost Ark, with Indiana and Marion now exhuming artifacts in China. Indiana Jones and Marion Ravenwood are then literally “Shanghaied” by Chinese Tong gangsters into retrieving the eponymous mask before it falls into the hands of the villainous Colonel Oni.

The film was released in May of 1984 and performed well at the Box Office. The current critical consensus is that it’s notably weaker than its predecessor, but it was a major hit upon its release. The film is largely considered a classic by fans, though it has received criticism for its portrayal of Chinese mythology, its positive portrayal of Mao Zedong, and its dark themes and voilence.

Cast & Crew:

Produced by: Kathleen Kennedy

Associate Producer: Lisa Henson

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Executive Producers: George Lucas & Steven Spielberg

Written by: Lawrence Kasdan (additional script work by Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz)

Story by: George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Lisa Henson

Starring:

Harrison Ford (Indiana Jones)

Karren Allen (Marion Ravenwood)

Jonathan Ke Quan (Wu Lì, aka “Willie”)

Bolo Yeung (Hóu, aka “Short Round”)

Tatsuya Mihashi (Colonel Yamato Oni)

George Takei (Major Domo)

Roy Chiao (Lao Che)

David Carradine (Abner Ravenwood)

Tobgyal (Guanyin, Buddhist monk at Cittamanas Temple in the Himalayas)

Sammo Hung (Da Goh, Taoist Monk from Hóu Hóngsè temple on the Yangtse)

Synopsis

The movie begins

in media res with the Paramount logo dissolving into a steep-sided, green-topped mountain towering over the flat Chinese plain. Rice patties and small houses cover the landscape. Suddenly a Japanese dive bomber flies overhead from behind camera and banks off to the left. An explosion rocks the peaceful scene. We are suddenly in the middle of a war zone as Kuomintang soldiers attempt without luck to hold back an assault by Imperial Japanese Army forces. The Chinese forces break into retreat as the Japanese soldiers and tanks overrun the plain.

Colonel Yamato Oni appears with a menacing fanfare. Major Domo walks up with a Kuomintang soldier who surrendered, which Oni considers “Disgraceful.” He promises the prisoner freedom in exchange for intelligence, which the prison gives, only to be beheaded by Oni with his katana. “Major, release this man,” Oni says.

As the guards go to bury the body, one with a shovel over his shoulder, the scene segues to a shovel scooping up dirt. It then pans to reveal a large archeological site with diggers and surveyors. A title card says “Xi'an Province, Republic of China, 1938.” Workers exhume terracotta soldiers and other artifacts[1]. One worker starts excitedly calling and runs, holding an artifact. He takes it to where Indiana Jones, back to camera, stands overlooking the dig. Marion Ravenwood approaches, asking “What is it?” Indy cleans it off, revealing the glow of jade.

We now see Indy’s face. “Exactly what we came for, doll!” he says, smiling.

The scene now cuts to a tent where Indy and Marion are cleaning off the jade urn with Marion’s father Abner Ravenwood (a cameo by David Carradine) looking on. He congratulates them. “The ashes of Qin Shi Huang, first Emperor of China! You’ll both be wealthy and famous!”

“This isn’t about fortune and glory, Abner,” says Indy, looking illuminated by the find.

That night, Indy captures a food thief: a small orphan boy (parents killed in the war) named Wu Lì, whom Indy calls “Willie”. He wants to send Willie to a refugee camp (“I’m not here to babysit”), but Marion stops him, suggesting they have a duty to help the less fortunate.

They are soon all interrupted by shrieking security whistles. “We’ve got trouble,” says Indy. “They not with me,” says Willie when they look at him.

The camp is soon being overrun by Tong gangsters. One, a short but stocky man, Hóu, is beating up the guards like they were nobodies, using kung fu moves (specifically Hóu-Quán). Indy mocks him as “Short Round” and draws his pistol, but Hóu uses a chain to pull it from his grasp. The two continue to fight, but Indy is definitely on the losing side. “Dad, do something!” says Marion, but Abner says “Do I look like I know kung fu?” Marion sighs, runs, and grabs the gun, but is unable to get a clear shot.

Eventually, more well-armed gangsters appear, forcing Indy and Marion to surrender. The gangsters take the urn and compel Indy and Marion to get into a car.

The scene segues to a bright, well-lit 1930s club covered in art deco designs. A Chinese chanteuse sings a Mandarin cover of “Anything Goes” as dancers perform around her. A Title Card says “Shanghai, China.” Indy Marion, and Willie are taken to see the gangster Lau Che, who is handed the urn and “appreciate the gift” but has “one more thing I need for you to get me.” Lau Che reveals that he has a map to the Cittamanas Temple, which contains “relics related to the real Monkey King,” in particular “a mask, said to contain the spirit of the Monkey King himself. Silly peasant stories, of course.” He unrolls an ancient scroll to reveal a picture of the mask. Marion lambastes Lau for his “greed,” but he insists he’s a “patriot” and that the money will fund the war effort. Indy expresses that he “doesn’t care” about Lau’s petty politics. The whole time, a shady looking man with Tojo glasses and a toothbrush mustache looks on from an adjacent table. The leitmotif of Colonel Oni plays for a second.

It segues to a drive down the streets of Shanghai, past abject poverty in stark contrast to the glamor of the club, to an airport, where Indy, Marion, Willie, and (to Indy’s annoyance) Hóu/Short Round board a Lockheed Electra, Lau Che wishing “happy trails, Doctor Jones!”.

It pans back to reveal the shady man in the Tojo glasses looking on. The leitmotif of Colonel Oni plays again as the shady character picks up a payphone. “Tell the Colonel that the plane is headed to Tibet,” he says.

The plane then travels through the clouds, superimposed over a map, with the Indiana Jones theme playing in the background as a red line traces a journey from Shanghai, to Chongqing, to Lhasa.

The plane lands at a small mountain airport. Soon we see Indy, Marion, Willie, and Hóu riding donkeys through the winding mountain passes of the majestic Himalayas. Indy describes how, according to legend, the Monkey King, while escorting the monk Tang Sanzang, played a prank on a mountain hermit, who turned out to be the Bodhisattva Guanyin. Guanyin then, as punishment for the insolence, stole the face from the Monkey King and with it his heavenly powers. The temple Lau Che was sending them to, Cittamanas Temple, was according to legend built upon the site of the hermit’s shack[2].

From the shadows of a tree trunk in the foreground, a pair of eyes open up, drawing out attention to a hidden, black-clad figure.

At the temple they are greeted by a Buddhist monk, who welcomes them and offers them shelter. Over dinner when Indy brings up the legend, the monk laughs, and says “there are no mystical masks here, my friend.”

Later, Indy and the team discover a secret doorway. They are forced to go through a room full of crawling bugs and other obstacles.

Back outside, we see a group of ninjas suddenly overrunning the temple, cold-bloodedly slaughtering the unresisting monks. The head monk stands quietly at the door throughout all of this. One ninja, who is bowed to by the others, walks up to the Monk and removes his mask: it’s Colonel Oni. “You will not find what you seek, brother,” says the monk. Oni beheads him with his katana.

Back in the caves, Indy, Marion, Willie, and Hóu discover a room decorated with depictions of the Monkey King. In the center, lit by a single beam of moonlight, is a magnificent golden mask. Despite Indy’s warnings of a possible trap, Hóu walks up and grabs it and hands it to Indy. Indy quickly declares the mask “a fake” and instead looks at one of the paintings on the wall. From the painting he deciphers that the true mask is “where the Three Rivers Meet” at the legendary “temple of Hóu Hóngsè.”

They emerge from the caverns to find that Oni and the ninjas[3] have overrun the temple. They demand that Indy and crew surrender, but Hóu grabs a bamboo pole and begins fighting back the ninjas. Now Indy, Marion, and Willie have no choice but to scramble and fight their way through the ninjas in a running, swinging, leaping melee among the cliffhanging decks of the mountainside temple. Indy, using his whip, swings past two ninjas, runs, and grabs a small package from their stack of gear that’s clearly labelled “Emergency Raft; Auto-inflatable.”

He runs to the edge of the mountainside and inflates the raft as Marion and Willie join him. “Get in!” he yells. “Are you crazy?” asks Marion. “GET IN!!” Indy, Willie, and Marion get in the raft. “Short Round, come on!” yells Indy, but Hóu shoos them away. “Don’t have to tell me twice,” says Indy, and launches the three of them over the edge. They start to slide down the steep cliffside, through snow and ice, past forests, off of a cliff, and into a raging river. They’re pulled along down the river until the rapids finally end and they can relax. “You Yankees are crazy!” yells Willie.

Up at the temple, Hóu is still fighting the Ninjas, who have him backed up to a steep cliff. Oni finally draws a gun and shoots him, causing him to fly off the cliff, out of sight. Major Domo walks up to Oni with the gold mask and bows. “Sir, we have the mask!”

“No. It’s a fake. If anyone knows where the real mask is, it’s him,” pointing to where Indy went.

“How will we find them?” asks Domo.

“This river only runs one direction”.

Indy, Marion, and Willie arrive, soaked, to Hóu Hóngsè temple on the Yangtse where the “three rivers” converge. They are greeted by a Taoist monk named Da Goh and given a reprieve. They learn that yes, the mask is here, but it must stay “under the mountain”. Suddenly alert, the monk warns them that “evil is coming; quickly!” and opens a secret door behind a Monkey King mural. He tells them that the mask is in the tunnels and that they must take the mask “far away”. However, he warns them that “the cost of immortality is the soul.” Indy declares he has no need for immortality. They search through the tunnels and find the mask nonchalantly sitting on a shelf cut into the living rock. It is bronze and far less elegant than the gold fake.

But before Indy and the team can escape with the mask, Col Oni arrives with some soldiers and ninjas. There’s a big fight between the ninjas and monks. Witnessing everything through a gap in the floor, Marion says that they need to find another way out. Willie reports there’s no other way. Oni, whose ninjas finally overrun the temple, and who has beheaded Da Goh, discovers Indy and the team through the gap and diverts river water into the secret tunnels, which start to slowly flood. After some tense moments, Col. Oni offers Indy and the team their “freedom” in exchange for the mask. They relent and pass the mask through the gap, and then Major Domo says, “we can now take this to the Emperor.”

They start to leave when Marion says, “Wait, you promised us our freedom!” “Yes,” says Oni, “Freedom from this cycle of the wheel of life. May your next life be better.” They leave, Marion screaming.

Just as the water is about to cover their heads, Hóu arrives in the empty temple and smiles, somehow there and alive. He breaks them out of the tunnels by physically ripping the floor up with his bare hands. As they dry themselves, the mute Hóu keeps insistently pointing north, but Indy says, “No, the mask will soon be on a plane to Japan,” insisting he’s not going to Tokyo in the middle of a war for Lau Che. But Hóu keeps pointing to a mural of an ancient map of China on the wall, specifically pointing to Manchuria. “Of course,” says Indy “there’s

another Emperor!”

The scene fades into a map & travel sequence where they board a sketchy tri-motor and fly through Xian over the Great Wall to Ulan Bator in Mongolia, then fly west through the night into Japanese-occupied Manchuria.

It’s night and they’re driving an old truck along forest roads. A Title Card says “Manchukuo (Japanese Occupied Manchuria)”. Indy exposits about how the Japanese put the old Qing Emperor Xuantong on the throne of Manchuria as a puppet monarch. Suddenly, armed men stop their vehicle. Hóu suddenly bolts into the night, seeming to vanish. “Who are they?” asks Willie.

“Communist rebels,” says Indy, nervously.

A smiling Mao Zedong appears, holding a submachine gun, as a riff from the People’s Republic National Anthem “March of the Volunteers” plays.

The scene transitions to a fabulous palace at night, where a big gala is happening. A Title Card reads: “Imperial Palace, Hsinking.” Col. Oni visits and bows low to Emperor Xuantong and formally gifts the Emperor with the golden mask. The Emperor smiles, and says, “ah, yes, they say the power of the Monkey King will be gifted to whomever shall wear this mask!” he tries it on and nothing happens. All laugh, and he thanks Oni for the “Great gift.”

Later, in private, Maj. Domo notes that Oni gave him the fake mask, to which Col. Oni says that the true mask is reserved for the “true Emperor,” to which Maj. Domo smiles “to Japan then.”

“No,” says Oni, “to the temple on Mount Huaguo. I am now the true Emperor.”

“You would betray Hirohito? Blasphemy!” yells Major Domo, who is promptly beheaded by Oni. Oni then raises the real mask and smiles.

Indy, Marion, and Willie are now shown to be hanging out with the Red Army in a hidden camp in a poor village. The Reds are treating them well. A Red Army soldier points out the poverty of the locals to Indy and describes the abuses of the Japanese army upon the populous and Indy realized he can’t just sit on the sidelines anymore.

Indy then talks with Mao, who is pointing to a map. “He says that a small Japanese force has travelled into the Khingan Mountains,” Indy tell Marion. “It must be Oni.” Marion asks how he knows, and Indy indicates that the mountains are believed to be the home of Mount Huanguo from the legend. Indy exposits that, once there, Oni would be able to perform an ancient sacrificial rite that will imbue him with the powers of the Monkey King. Once he does so, he’ll “be able to harvest the Peaches of Immortality.”

The team parts ways with the Red Army and travels to the ruins of the mountain temple, where they sneak past the Japanese Army soldiers and, following Willie’s guidance, they find the secret sacrificial chamber deep inside the mountain. Inside, Oni, wearing ceremonial robes and the true mask, is leading an ancient rite. He sacrifices a shrieking monkey with a knife[4] and, before their eyes, is engulfed by magical light and tendrils. “It’s too late!” says Marion, quietly.

“Yes, too late,” says Indy, looking back and raising his hands as a pistol is pointed at him.

The team, tied up, is now, is brought before Oni, who is still glowing unnaturally. He’s acting and moving strangely, almost like a monkey. He laughs, “Yes, it is good of you to join us, Dr. Jones, for it is time to harvest the Peaches of Immortality.” The camera zooms in on Indy’s chest. We can hear his beating heart.

“The heart,” says Indy, “The Peaches of Immortality are harvested from the heart. The ‘garden of the heavens’ could translate in ancient Chinese[5] to ‘the center of life and spirit’.”

Marion is suddenly dragged towards the alter insisting the whole time that if he needs a virgin sacrifice, he’s “wasting his time.” In the background, Willie is slowly escaping his bonds. Just as Marion is getting tied to the alter and Oni descends upon her with the knife, grasping hand reaching towards her audibly beating heart, an explosion and gunfire can be heard.

Outside, the Red Army is attacking the Japanese. Inside the temple Hóu and Mao run in, side by side, fighting their way through the Japanese soldiers and ninjas.

Marion’s imminent execution is paused as Oni directs the fighting. The soldiers holding Indy leave him and run to join the fighting. Meanwhile, Willie escapes his bonds and slips back into the shadows. He’s soon untying Indy’s bonds.

Oni descends again upon Marion, but the newly freed Indy attacks him. They fight, but Indy is barely holding his own against the supernaturally empowered Oni. Willie runs to rescue Marion as the hero and villain fight. Indy and Oni struggle and wrestle and Oni’s hand moves towards Indy’s heart. Just as Indy is about to get his heart ripped out, Hóu appears, and picks up and throws Oni. “About time you showed up, Short Round,” says the battered Indy.

Hóu and Oni now fight, both using moves from Hóu-Quán, or “Monkey Kung Fu”, but Hóu is unstoppable, and soon rips the mask from the screaming Oni and puts it on himself. The mask merges with his face in a dazzling effects display.

Now Hóu

is the Monkey King, and (as is now clear) was all along. He visibly rips Oni’s still beating heart from his chest, which transforms in a blaze of fire into a glowing peach. He lifts it to his mouth and the scene cuts to the reunited Indy, Marion, and Willie, who cringe in reaction. Chin dripping with glowing liquid, Hóu/Monkey King then vanishes, laughing, in a flash of light.

After the battle, Indy, Marion, and Willie bid farewell to Mao and his fighters and head back towards non-occupied China on an ox cart. Indy exposits that with the Monkey King free in the world again, times are about to become “Interesting”.

Marion asks how they’ll explain the situation to Lau Che and Indy replies that they’ll “tell him the truth. Hóu stole the mask and disappeared.”

“What next, then?” asks Willie.

“Well,” says Indy, “This war isn’t going to end by itself. I’d say the people of China could use some help.”

The Indiana Jones theme plays as they ride off into the setting sun.

Production

Production on “Indiana Jones 2” began in the summer of 1981 almost immediately following the success of

Raiders of the Lost Ark. Early brainstorming sessions including George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy, and Lisa Henson (then an intern for Lucas) discussed a variety of scenarios that eventually resulted in a film treatment from Henson titled “The Mask of the Monkey King”. This treatment was edited by Lucas and Spielberg and handed in 1982 to Lawrence Kasdan, who’d written

Raiders of the Lost Ark and

The Empire Strikes Back. Kasdan produced a script titled

Mask of the Monkey King that contained and expanded upon the set pieces from the Henson treatment while adding structure and character arcs.

This script reportedly did not include the heart-ripping scenes and was generally lighter in tone than the eventual script. In 1983 George Lucas, who was going through a painful divorce, asked Kasdan to revise the script with these darker elements. Kasdan felt the additions were “mean spirited and ugly” and politely turned down the request. Lucas instead handed the script to Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz to script-doctor, and the darker elements were added. They also added the nickname “Short Round” for Hóu, based upon Huyck's dog, whose name was in turn derived from a character in

The Steel Helmet.

Production ran into difficulty fairly quickly, with the People’s Republic of China at first refusing to allow filming in the country, which was at the time only starting to open up to the world under Deng Xiaoping. Associate producer Lisa Henson reportedly contacted Joan Ganz Cooney of the Children’s Television Workshop, who had recently arranged a

Big Bird in China special, coincidentally also featuring the Monkey King as a character. They reportedly arranged back-door contacts through the earlier production and got the picture greenlit.

Even with this arrangement made, the PRC insisted on several changes. Most notable of these was the removal of all portrayals of magic, the supernatural, and superstition, leading to the infamous “Chinese Release” version of the film. They also insisted on adding in scenes with Mao Zedong, and insisted that the portrayal of Mao be both positive and heroic. Finally, the planned motorcycle chase scene atop the Great Wall intended for the intro was deleted, as the Chinese considered this cultural desecration. Instead, they filmed the “battle scene” that introduced antagonist Colonel Oni.

Filming began in the PRC in June of 1983 with location shoots in Manchuria, Tibet, Xi’an, Three Gorges park, and the Yangtze delta. Other shots were filmed on sound stages at Pinewood Studios and Paramount. Principal photography ended that fall with editing and post-production going into the spring of 1984.

Differences in the “Chinese Release”

The Chinese authorities mandated several “changes” to the film before they permitted Amblin and Lucasfilm to film in China. Among these were the addition and sympathetic portrayal of Mao Zedong and his Red Army, the removal of the motorcycle chase scene on the Great Wall, and the removal of any reference to the supernatural as actually existing. This latter resulted in the creation of two versions of the film: one for China, one for wide release.

In the Chinese version, the mask has no powers. That the Japanese and the Manchukuo Emperor Xuantong believe this legend is portrayed as proof of their superstitious ignorance. The special effects surrounding the sacrifice scenes are removed and the ceremony is played as just a mindless cult performing an empty, superstitious ceremony. Instead of transforming into the Monkey King, Hóu is portrayed as a crazy man who now

thinks that he is the Monkey King. And simply runs off, laughing, wearing the mask.

Differences in the “Taiwan Release”

The Taiwan release, by comparison, deletes the scenes with Mao Zedong and portrays the Red Army soldiers as being “loyal militias in the service of the legitimate [i.e. Kuomintang] government”. The opening battle scene was also edited to portray the Kuomintang fighters as being more heroic and suggests that the captured prisoner who betrays his fellow soldiers was really a Maoist.

Differences in the “Japanese Release”

In the Japanese release, the “blasphemy” and dishonorable action of Colonel Oni was pointed out by lesser officers on occasion and the average Japanese soldiers are portrayed in a more sympathetic light. A scene available only in the Japanese release shows some Japanese officers discussing how to react to Oni’s increasingly rebellious behavior when Oni discovers them and they submit to be executed by him. Furthermore, the name “Yamato Oni” (大和鬼), which could be interpreted as “Japanese Ogre”, was changed to Oniya Mato (おにや まと), which the Japanese audience could tell was referencing and 大和, but also 矢 (arrow) and 的 (target, mark, bullseye). This was read as 鬼矢 的, and thus could be interpreted as both “Ogre of Great Harmony” and “Target of Ogre's Arrow”[6], which resonated with both his self-image and his ultimate fate at the hands of Hóu.

Deleted Scene

The original screenplay began with Indy attempting to liberate the urn of Emperor Qin Shi Huan from a group of thuggish looters, culminating in an exciting motorcycle chase across the top of the Great Wall. Eventually, Indy escapes with the urn and makes it back to the camp with Marion and Abner, where the film blends in with the final cut just before the celebration of the urn’s possession and Willie’s introduction. However, Chinese government officials objected to the scene, considering it desecration of a cultural landmark, objecting even to simulating the chase on a Great Wall set. The production team relented, creating the battle scene opening instead.

Reception, Box Office, and Legacy

Mask of the Monkey King broke attendance records for the time, earning an astounding $45 million on its opening weekend. It would go on to gross over $340 million worldwide, counting $9 million in revenues from China, one of the first western movies to screen in the People’s Republic.

Mask of the Monkey King screened to mostly positive reviews, with Siskel and Ebert giving it two thumbs up, but noting that the violence was “probably not appropriate for younger viewers.” Reviews and audiences alike tended to be divided between enjoying the movie and being disturbed by the imagery. It currently has an A- rating from MovieGrade.

The movie is generally considered a Classic, though consensus considers it one of the weaker films in the Indiana Jones franchise. The film has garnered controversy both at the time of release and more recently, both for its loose interpretation of Chinese legends and the

Journey to the West and for its stereotypical portrayal of both the Chinese and Japanese people. It has faced accusations of racism and cultural appropriation, though these accusations are rejected by Lucas and Spielberg. It was also dismissed by many, particularly on the political right, for its sympathetic portrayal of Mao Zedong.

Trivia

In an Easter egg for Mandarin speakers, Wu Lì, annoyed with the “Willie” nickname, asks Indy if he should be called “Ēn dì” (恩 地), or, roughly, “benevolent dirt”, a fitting name for an archeologist who takes in orphans!

The name “Yamato Oni” began simply as “Colonel Oni” in Lisa Henson’s original treatment. Spielberg added the name “Yamato” to it based upon the name of the WW2 Japanese battleship. This led to challenges when the name (大和鬼) effectively translated to “Japanese Ogre”. Thus, the name was changed in the Japanese release to Oniya Mato (おにや まと or 鬼矢 的), and thus could be interpreted as both “Ogre of Great Harmony” and “Target of Ogre's Arrow”.

Lau Che’s club in Shanghai is named “Club Obi Wan” in reference to George Lucas’

Star Wars films. This parallels a reference in

Raiders of the Lost Ark where hieroglyphics of C-3PO and R2-D2 can be seen in the Ark vault. This has led to “shared universe” fan theories.

Abner Ravenwood’s comment about “Do I look like I know Kung Fu?” is an Easter egg related to the actor David Carradine’s role in the 1970s TV series

Kung Fu.

Several filming locations for the river ride and Hóu Hóngsè temple are now underwater following the completion of the Three Rivers Gorge Dam.

Actor Pat Morita plays a small role as a Japanese Sergeant.

Actor George Takei’s bathos-filled “Blasphemy!” has become the source for many “Net Wit[7]” images, alongside fellow Star Trek alum William Shatner’s “Khaaan!”.

The at times shocking violence of the film, in particular the heart-ripping and implied heart-eating, spurred the development of the 13-and-up “T” for “Teen” rating with the MPAA[8].

This film was Lisa Henson’s first production credit.

[1] Anachronism alert! The Terracotta Army was first discovered in 1974.

[2] And if this all sounds to you like an absolute massacre of

Journey to the West, you’re right!

[3] Good name for an ‘80s synth pop band?

[4] The actual killing scene is not shown, and instead cuts to Marion’s reaction.

[5] How’s this for a bad ‘80s gwáilóu “interpretation” of

Journey to the West and Chinese legend?

[6] Fedora-tip to

@Damian0358 for this idea.

[7] We’d call them “memes”.

[8] Just as

Temple of Doom spurred the creation of our timeline’s PG-13 rating.

/https://www.theactivetimes.com/sites/default/files/2019/08/08/00_HedFireworks.jpg)