Chapter 4: Ain’t Nothin’ but a Hound Dog

Post from the Riding with the Mouse Net-log by animator Terrell Little.

My first job at Disney was as an inbetweener on The Fox and the Hound. Like a lot of the new employees, I hated the movie, but not for the same reasons. Most of the Rat’s Nest hated it for being a rehash of the same tired old Disney formula and playing it too safe with the animation. Brad Bird had gotten fired for making his negative opinions of it known[1].

I hated it because it was segregationist garbage[2] and a painful reminder of my past.

I couldn’t believe anyone wanted to tell such an awful, outdated story. How could Woolie not see the terrible lesson we were telling? Stay with your own. Don’t mix with other races. It will all end in tragedy. I expressed my concerns to Ron Clements, who was taking lead on the story, but he had a different take. “It’s about prejudice and how it separates us[3],” he said. “It’s a tragedy, not a positive example.”

Easy for him to say. He didn’t grow up black in Alabama!

Still, though, I took his view to heart. I’d do my best to focus on it as a tragedy of prejudice and ignore what I feared could be construed as Jim Crow propaganda. It’s not like Disney has the best record there, as my family loved to remind me when I took this job.

Oh well. Paycheck’s a paycheck. And the gig came with a few perks. I got to meet the stars who voiced the characters. Cory Feldman before he got famous. Mikey Rooney, who regaled us all with Old Hollywood stories. Pearl Bailey, who buried Steve Hulett’s face in her cleavage to everyone’s amusement. Oh, and former child star Kurt Russell, just before his big break out in Escape from New York. He still sported his GI Blues Elvis hair, since he was filming the TV Elvis Biopic at the time. Ironically, another reminder of life in the old south. It would win him an Emmy. Here, he was voicing the adult Copper, the eponymous Hound[4].

I had “You Ain’t Nothin’ But a Hound Dog” stuck in my head for a week.

But The Fox and the Hound was overall a good learning experience and, in hindsight, quite an honor to be a part of. I got to share in that strange passing-of-the-torch moment where the Old Men like Woolie and Art Stevens were working with the soon-to-be big names like Lassiter and Clements. It was also a passing-of-the-torch moment for the actors, the old stars (Rooney and Bailey) passing the torch to the new one (Feldman) and an actor who spanned both eras (Russell).

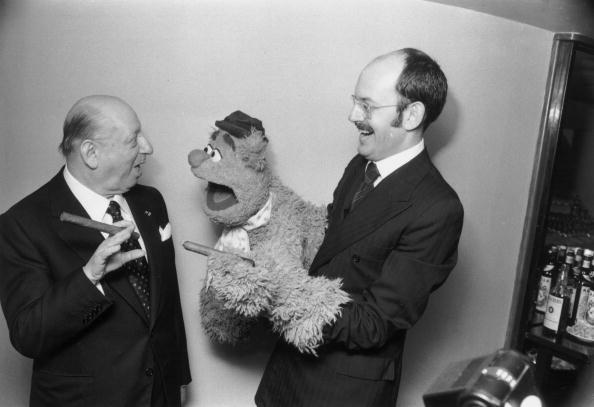

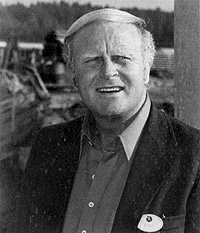

It was also the first project that Jim Henson was associated with, though most of the film was already in the can by the time he joined. In fact, Jim’s only contributions were two recommendations, both ignored by Art and Woolie.

First, he wanted to add a scene at the end where two of Tod and Copper’s children meet and form a friendship. Ron Clements rejected the idea as an attempt to force in a “happy ending”, fearing it would undermine the power of the bittersweet finale.

But I got it. It wasn’t “happy” Jim was going for, it was “hopeful”. The promise of the next generation overcoming the mistakes of the prior ones. Time moving forward, not backwards. Given my thoughts on the film, I fully supported the add, but who the hell was I?

The second recommendation Jim had was one close to Rod’s heart: he too wanted Chief to die.

Rod was pressing hard for Chief to die, as we all were on the creative side. It made no sense for Copper to go on a vengeance quest against his old friend if Chief only breaks his leg. There were no stakes. There was no motivation. We all knew it, but Art Stevens and the rest of the producers and directors weren’t going to have it. Disney would not kill off a central character. It wasn’t the Disney way.

Sure, if you don’t count Bambi’s mom.

Jim agreed wholeheartedly. He pleaded with Woolie, Art and Ron Miller. His pleas, like Ron Clements’, were rejected. Chief would live, and the story would suffer for it. We were all just cryin’ hound dogs to them.

Jim’s opinion (and ours) was validated when the film premiered. The film received mixed reviews. Many critics specifically called out Chief’s survival as a narrative weak point. The film made a decent profit, but it was a box office disappointment compared to Ron’s expectations. To this day, it’s few people’s favorite Disney cartoon.

But Jim accomplished one thing: by fighting for us, he earned our eternal gratitude. Of all the execs, Jim stood with us.

[1] I know there was a lot of hope that this would be butterflied, but as best as I can tell Bird was fired prior to 1980, seeing as how he was an animator for Animalympics, which aired in February of 1980. Besides, even Henson would have a hard time saving him when he was pretty openly insubordinate to upper management.

[2] Some have made this accusation.

[3] This, I believe, is the lesson Disney was trying to impart.

[4] All of this is recounted by Steve Hulett in Mouse in Transition.

Post from the Riding with the Mouse Net-log by animator Terrell Little.

My first job at Disney was as an inbetweener on The Fox and the Hound. Like a lot of the new employees, I hated the movie, but not for the same reasons. Most of the Rat’s Nest hated it for being a rehash of the same tired old Disney formula and playing it too safe with the animation. Brad Bird had gotten fired for making his negative opinions of it known[1].

I hated it because it was segregationist garbage[2] and a painful reminder of my past.

I couldn’t believe anyone wanted to tell such an awful, outdated story. How could Woolie not see the terrible lesson we were telling? Stay with your own. Don’t mix with other races. It will all end in tragedy. I expressed my concerns to Ron Clements, who was taking lead on the story, but he had a different take. “It’s about prejudice and how it separates us[3],” he said. “It’s a tragedy, not a positive example.”

Easy for him to say. He didn’t grow up black in Alabama!

Still, though, I took his view to heart. I’d do my best to focus on it as a tragedy of prejudice and ignore what I feared could be construed as Jim Crow propaganda. It’s not like Disney has the best record there, as my family loved to remind me when I took this job.

Oh well. Paycheck’s a paycheck. And the gig came with a few perks. I got to meet the stars who voiced the characters. Cory Feldman before he got famous. Mikey Rooney, who regaled us all with Old Hollywood stories. Pearl Bailey, who buried Steve Hulett’s face in her cleavage to everyone’s amusement. Oh, and former child star Kurt Russell, just before his big break out in Escape from New York. He still sported his GI Blues Elvis hair, since he was filming the TV Elvis Biopic at the time. Ironically, another reminder of life in the old south. It would win him an Emmy. Here, he was voicing the adult Copper, the eponymous Hound[4].

I had “You Ain’t Nothin’ But a Hound Dog” stuck in my head for a week.

But The Fox and the Hound was overall a good learning experience and, in hindsight, quite an honor to be a part of. I got to share in that strange passing-of-the-torch moment where the Old Men like Woolie and Art Stevens were working with the soon-to-be big names like Lassiter and Clements. It was also a passing-of-the-torch moment for the actors, the old stars (Rooney and Bailey) passing the torch to the new one (Feldman) and an actor who spanned both eras (Russell).

It was also the first project that Jim Henson was associated with, though most of the film was already in the can by the time he joined. In fact, Jim’s only contributions were two recommendations, both ignored by Art and Woolie.

First, he wanted to add a scene at the end where two of Tod and Copper’s children meet and form a friendship. Ron Clements rejected the idea as an attempt to force in a “happy ending”, fearing it would undermine the power of the bittersweet finale.

But I got it. It wasn’t “happy” Jim was going for, it was “hopeful”. The promise of the next generation overcoming the mistakes of the prior ones. Time moving forward, not backwards. Given my thoughts on the film, I fully supported the add, but who the hell was I?

The second recommendation Jim had was one close to Rod’s heart: he too wanted Chief to die.

Rod was pressing hard for Chief to die, as we all were on the creative side. It made no sense for Copper to go on a vengeance quest against his old friend if Chief only breaks his leg. There were no stakes. There was no motivation. We all knew it, but Art Stevens and the rest of the producers and directors weren’t going to have it. Disney would not kill off a central character. It wasn’t the Disney way.

Sure, if you don’t count Bambi’s mom.

Jim agreed wholeheartedly. He pleaded with Woolie, Art and Ron Miller. His pleas, like Ron Clements’, were rejected. Chief would live, and the story would suffer for it. We were all just cryin’ hound dogs to them.

Jim’s opinion (and ours) was validated when the film premiered. The film received mixed reviews. Many critics specifically called out Chief’s survival as a narrative weak point. The film made a decent profit, but it was a box office disappointment compared to Ron’s expectations. To this day, it’s few people’s favorite Disney cartoon.

But Jim accomplished one thing: by fighting for us, he earned our eternal gratitude. Of all the execs, Jim stood with us.

[1] I know there was a lot of hope that this would be butterflied, but as best as I can tell Bird was fired prior to 1980, seeing as how he was an animator for Animalympics, which aired in February of 1980. Besides, even Henson would have a hard time saving him when he was pretty openly insubordinate to upper management.

[2] Some have made this accusation.

[3] This, I believe, is the lesson Disney was trying to impart.

[4] All of this is recounted by Steve Hulett in Mouse in Transition.

Last edited: