Part I; Brillstein I: the POD

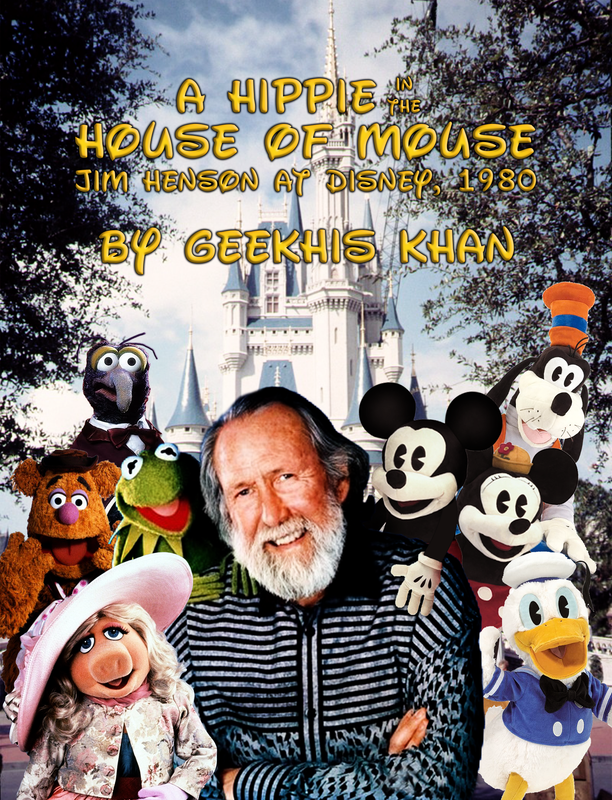

A Hippie in the House of Mouse

The Incredible Story of Jim Henson’s Amazing Tenure at the Walt Disney Company

Image courtesy of @Nerdman3000

Part I: Froggy Went a’ Courtin’

Chapter 8, Frog Eats Mouse?

Excerpt from Where Did I Go Right? (or: You’re No One in Hollywood Unless Someone Wants You Dead), by Bernie Brillstein (with Cheryl Henson[1])

You can blame it all on me.

It was late July of ’79 and Jim Henson and I were having drinks at a bar in Manhattan. We’d just pitched The Dark Crystal to Paramount and gotten shot down. Hard. Jim was putting on his brave face, but I could tell he was taking it bad. I wondered if it was because of Michael Eisner, who was leading Paramount studios at the time. Eisner had been an early supporter of the Muppets back at ABC. He greenlit the Valentine’s Day special in ’73. He saw the potential when others didn’t. To Jim’s eyes he got it. That must have made the rejection that much more painful.

Jim said, “they look at me, and all they see is Kermit.” He meant Producers & Studio Heads. He was right.

Part of being a good agent is knowing what to say to your client and when, and over time you get to know them on a deep personal and emotional level. And I’d known Jim since Rowlf was doing Purina commercials. He always did things on his terms and in his own voice. Even the commercials. His greatest fear has always been losing creative control of his vision to some corporate committee. He needed a lift.

“There’re worse things to be than Kermit,” I said. The Muppets had made Jim a multi-millionaire. The Muppet Show was an international hit, pulling in tens of millions every year. The Muppet Movie was a blockbuster success. There was Oscar buzz. By the time it was all said and done it’d top $100 million between the box office, merch, tie-ins, and sponsorships.

Jim grunted, morose. I see this all the time with kids’ entertainers and comedians: they want to branch out, be recognized for something serious, something real. I saw it with my uncle Jack. I’d seen it twice already with Jim, first with Timepiece in the sixties (which earned him his first Oscar nom) and later with the Gortch skits on SNL (which didn’t go so well). For most talent it was an ego thing, but for Jim it was something more: a crusade to see puppetry recognized as a legitimate art form and more than just kids’ stuff. Crystal was more than just a new look for Jim – it was a burgeoning revolution in the artform. It was going to change everything. And he was losing valuable time.

“Fuck Paramount, and fuck Eisner,” I told Jim. “Here’s what you do: when you get back to London next week you pitch Lord Lew a two-picture deal. First the bait: a Muppet sequel. Then, the hook: Crystal. A movie for a movie[2].”

Jim nodded sadly. It’d work. He knew it. But it meant that The Dark Crystal, the movie he’d been itching to make for the last two years or more, his passion, would have to wait another two years or more while he produced another Muppet flick that his heart wasn’t invested in. He’d given his all to the Muppets for over two decades at this point, but he was itching for a new challenge. He’d do another Muppet film, certainly, and he’d put his all into it, but it wasn’t where he wanted to be.

I could have left it at that. He would have gone to Lew, gotten the deal, and made the two movies. I would have gone off to the Hamptons that weekend to lie like a beached beluga and cook in the sun like a goddamned tourist. I could have, but I didn’t.

Instead I opened my fat mouth like a schmuck. “I know, Jim,” I said. “Hollywood is hell. Unless you own the studio, your vision is at the whim of some asshole with an MBA more concerned with returns than with making magic.” I ordered another round and we went back to small talk. I began to put the whole thing behind me.

Apparently, he didn’t. About half an hour later he said, “Bernie, do you think I could buy Disney[3]?”

I had no idea if he was serious. Truth be told, it wasn’t completely insane. If there was a time to make a run on Disney it was then. Disney was struggling, and frankly had been since Walt kicked the bucket in ’66. The Black Hole had just landed like a wet turd in the theaters and their upcoming work was not inspiring confidence. Herbie Goes Bananas? Seriously? Even the hallowed animation studio, the heart and soul of the company, hadn’t produced anything worth a damn since The Rescuers. The only part of the company turning a steady profit was the theme parks. The running gag in Hollywood was that Disney was a real estate holding company that did movies on the side. Stocks were languishing, and it seemed to me only a matter of time before it got bought up. I’d honestly much rather see it in the hands of a good man like Jim with a real love for the property than see it chewed up and spit out in pieces by some corporate pirate like Vic Posner[4]. Even so, The Mouse would be a pretty big bite for a small fry like Jim, who managed less than a hundred people at the time.

I thought for a minute. “It won’t be easy,” I told him. “And it’ll take some time. You’ll need to put the Muppets in hock and, even then, you might not have enough capital. It’s a long-shot at best. You’d be risking everything.”

Jim grunted. Once again, I could have just kept quiet. He’d think it over, weigh the risks, and then likely fly back to Lew and pitch the two-picture deal. But if you’ve read this far you already know me and know exactly what comes next.

“It’s a gamble,” I continued, “but if you make it work there’ll be no one to tell you ‘no’.”

Jim raised his eyebrows and went “Hmm.”

I felt like I’d just handed Don Quixote his spurs, or Captain Ahab his harpoon. And I thought to myself “Bernie, you putz, you’re in it now.” And with that I consigned myself to weeks of pouring through accounting books, consulting lawyers, calling in favors, twisting nuts, and setting up Hollywood lunches. All to answer the simple question: “how does a frog swallow a mouse a hundred times his size?”

[1] In our timeline Bernie Brillstein partnered with David Rensin as co-author. This timeline has given him a new co-author. See if you can find Cheryl’s fantastic flamboyant fingerprints within Bernie’s bawdy banter!

[2] This is what happened in our timeline, though it was Producer David Lazer’s idea, not Bernie’s (let’s say he’s…misremembering). Lazer pitched the two-picture idea to Lord Lew Grade at ITC, who was producing The Muppet Show. The results were The Great Muppet Caper (1981) and, eventually, The Dark Crystal (1982), only right before the latter’s release disaster of a sort struck. Grade, in dire financial straits following 1980’s double box office disasters of Raise the Titanic and Can’t Stop the Music, sold his shares to Robert Holmes à Court, who then led a boardroom coup in ’82 that ousted Grade and claimed ITC for himself. Unlike Grade, who had a love for Henson and his art and gave him full creative freedom, Holmes à Court constantly interfered with Henson’s direction. Henson eventually took the huge personal gamble of buying back the rights to his own characters for $15 million out of pocket. The Dark Crystal then saw mixed reactions at the box office, ultimately becoming a cult classic whose genius was only belatedly recognized.

[3] Consider this the Point of Departure for this timeline. In Bernie Brillstein’s actual version of Where Did I Go Right? he relates the following: “In the early ‘80s, knowing Disney was vulnerable, Jim wanted to make a run at taking over the company, which was still under its old management team of Ron Miller and Roy Disney. It was just idle talk that never went anywhere” [pg. 327 of the hardcover version]. Jim Henson: The Biography clarifies this to happening in the year 1984, when Saul Steinberg was making his infamous run on Disney (Jim the White Knight?). Here I assume Brillstein inadvertently gave Henson the idea earlier.

[4] This, of course, happened in our timeline with corporate raider Saul Steinberg, who attempted a hostile takeover/greenmail scheme with the undervalued Disney in 1984. After a close-run fight, Disney bought him off for $325.5 million in cash. This led to Roy Disney leading his first great shareholder revolt which saw the fall of Ron Miller and Card Walker and the rise of Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeff Katzenberg. The rest, of course, is (for better and/or for worse) history.

The Incredible Story of Jim Henson’s Amazing Tenure at the Walt Disney Company

Image courtesy of @Nerdman3000

Part I: Froggy Went a’ Courtin’

Chapter 8, Frog Eats Mouse?

Excerpt from Where Did I Go Right? (or: You’re No One in Hollywood Unless Someone Wants You Dead), by Bernie Brillstein (with Cheryl Henson[1])

You can blame it all on me.

It was late July of ’79 and Jim Henson and I were having drinks at a bar in Manhattan. We’d just pitched The Dark Crystal to Paramount and gotten shot down. Hard. Jim was putting on his brave face, but I could tell he was taking it bad. I wondered if it was because of Michael Eisner, who was leading Paramount studios at the time. Eisner had been an early supporter of the Muppets back at ABC. He greenlit the Valentine’s Day special in ’73. He saw the potential when others didn’t. To Jim’s eyes he got it. That must have made the rejection that much more painful.

Jim said, “they look at me, and all they see is Kermit.” He meant Producers & Studio Heads. He was right.

Part of being a good agent is knowing what to say to your client and when, and over time you get to know them on a deep personal and emotional level. And I’d known Jim since Rowlf was doing Purina commercials. He always did things on his terms and in his own voice. Even the commercials. His greatest fear has always been losing creative control of his vision to some corporate committee. He needed a lift.

“There’re worse things to be than Kermit,” I said. The Muppets had made Jim a multi-millionaire. The Muppet Show was an international hit, pulling in tens of millions every year. The Muppet Movie was a blockbuster success. There was Oscar buzz. By the time it was all said and done it’d top $100 million between the box office, merch, tie-ins, and sponsorships.

Jim grunted, morose. I see this all the time with kids’ entertainers and comedians: they want to branch out, be recognized for something serious, something real. I saw it with my uncle Jack. I’d seen it twice already with Jim, first with Timepiece in the sixties (which earned him his first Oscar nom) and later with the Gortch skits on SNL (which didn’t go so well). For most talent it was an ego thing, but for Jim it was something more: a crusade to see puppetry recognized as a legitimate art form and more than just kids’ stuff. Crystal was more than just a new look for Jim – it was a burgeoning revolution in the artform. It was going to change everything. And he was losing valuable time.

“Fuck Paramount, and fuck Eisner,” I told Jim. “Here’s what you do: when you get back to London next week you pitch Lord Lew a two-picture deal. First the bait: a Muppet sequel. Then, the hook: Crystal. A movie for a movie[2].”

Jim nodded sadly. It’d work. He knew it. But it meant that The Dark Crystal, the movie he’d been itching to make for the last two years or more, his passion, would have to wait another two years or more while he produced another Muppet flick that his heart wasn’t invested in. He’d given his all to the Muppets for over two decades at this point, but he was itching for a new challenge. He’d do another Muppet film, certainly, and he’d put his all into it, but it wasn’t where he wanted to be.

I could have left it at that. He would have gone to Lew, gotten the deal, and made the two movies. I would have gone off to the Hamptons that weekend to lie like a beached beluga and cook in the sun like a goddamned tourist. I could have, but I didn’t.

Instead I opened my fat mouth like a schmuck. “I know, Jim,” I said. “Hollywood is hell. Unless you own the studio, your vision is at the whim of some asshole with an MBA more concerned with returns than with making magic.” I ordered another round and we went back to small talk. I began to put the whole thing behind me.

Apparently, he didn’t. About half an hour later he said, “Bernie, do you think I could buy Disney[3]?”

I had no idea if he was serious. Truth be told, it wasn’t completely insane. If there was a time to make a run on Disney it was then. Disney was struggling, and frankly had been since Walt kicked the bucket in ’66. The Black Hole had just landed like a wet turd in the theaters and their upcoming work was not inspiring confidence. Herbie Goes Bananas? Seriously? Even the hallowed animation studio, the heart and soul of the company, hadn’t produced anything worth a damn since The Rescuers. The only part of the company turning a steady profit was the theme parks. The running gag in Hollywood was that Disney was a real estate holding company that did movies on the side. Stocks were languishing, and it seemed to me only a matter of time before it got bought up. I’d honestly much rather see it in the hands of a good man like Jim with a real love for the property than see it chewed up and spit out in pieces by some corporate pirate like Vic Posner[4]. Even so, The Mouse would be a pretty big bite for a small fry like Jim, who managed less than a hundred people at the time.

I thought for a minute. “It won’t be easy,” I told him. “And it’ll take some time. You’ll need to put the Muppets in hock and, even then, you might not have enough capital. It’s a long-shot at best. You’d be risking everything.”

Jim grunted. Once again, I could have just kept quiet. He’d think it over, weigh the risks, and then likely fly back to Lew and pitch the two-picture deal. But if you’ve read this far you already know me and know exactly what comes next.

“It’s a gamble,” I continued, “but if you make it work there’ll be no one to tell you ‘no’.”

Jim raised his eyebrows and went “Hmm.”

I felt like I’d just handed Don Quixote his spurs, or Captain Ahab his harpoon. And I thought to myself “Bernie, you putz, you’re in it now.” And with that I consigned myself to weeks of pouring through accounting books, consulting lawyers, calling in favors, twisting nuts, and setting up Hollywood lunches. All to answer the simple question: “how does a frog swallow a mouse a hundred times his size?”

[1] In our timeline Bernie Brillstein partnered with David Rensin as co-author. This timeline has given him a new co-author. See if you can find Cheryl’s fantastic flamboyant fingerprints within Bernie’s bawdy banter!

[2] This is what happened in our timeline, though it was Producer David Lazer’s idea, not Bernie’s (let’s say he’s…misremembering). Lazer pitched the two-picture idea to Lord Lew Grade at ITC, who was producing The Muppet Show. The results were The Great Muppet Caper (1981) and, eventually, The Dark Crystal (1982), only right before the latter’s release disaster of a sort struck. Grade, in dire financial straits following 1980’s double box office disasters of Raise the Titanic and Can’t Stop the Music, sold his shares to Robert Holmes à Court, who then led a boardroom coup in ’82 that ousted Grade and claimed ITC for himself. Unlike Grade, who had a love for Henson and his art and gave him full creative freedom, Holmes à Court constantly interfered with Henson’s direction. Henson eventually took the huge personal gamble of buying back the rights to his own characters for $15 million out of pocket. The Dark Crystal then saw mixed reactions at the box office, ultimately becoming a cult classic whose genius was only belatedly recognized.

[3] Consider this the Point of Departure for this timeline. In Bernie Brillstein’s actual version of Where Did I Go Right? he relates the following: “In the early ‘80s, knowing Disney was vulnerable, Jim wanted to make a run at taking over the company, which was still under its old management team of Ron Miller and Roy Disney. It was just idle talk that never went anywhere” [pg. 327 of the hardcover version]. Jim Henson: The Biography clarifies this to happening in the year 1984, when Saul Steinberg was making his infamous run on Disney (Jim the White Knight?). Here I assume Brillstein inadvertently gave Henson the idea earlier.

[4] This, of course, happened in our timeline with corporate raider Saul Steinberg, who attempted a hostile takeover/greenmail scheme with the undervalued Disney in 1984. After a close-run fight, Disney bought him off for $325.5 million in cash. This led to Roy Disney leading his first great shareholder revolt which saw the fall of Ron Miller and Card Walker and the rise of Michael Eisner, Frank Wells, and Jeff Katzenberg. The rest, of course, is (for better and/or for worse) history.

Last edited: