Well, @El Pip did mention that the changes made will have to suit British tastes, so changing the time period to reflect the basic charm of "the good old days" to a few decades prior would fit the feeling, so to speak. In other words, I'd go with what you suggested for a British Happy Days.Not sure when you'd set a British Happy Days, the 50s weren't the 'happy time' it was the Americas so I would advise against a direct swap. You could do it in the 20s or 30s before the Depression hits.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Hippie in the House of Mouse (Jim Henson at Disney, 1980)

- Thread starter Geekhis Khan

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Well show that can be used by the British Television:

- Little House on the Praire...damn if i don't liked that show, but my grandma loved (with the BIG VALLEY) so i was more or less 'forced' to watch it

- Lost in Space

- The Six-Million Dollars Man

- Barney Miller

- Gomer Pyler M.C.

- Maverick or Gunsmoke..

- Little House on the Praire...damn if i don't liked that show, but my grandma loved (with the BIG VALLEY) so i was more or less 'forced' to watch it

- Lost in Space

- The Six-Million Dollars Man

- Barney Miller

- Gomer Pyler M.C.

- Maverick or Gunsmoke..

I actually love this idea. Why not make that timeline this timeline? Probably not "lots", but there's certainly no reason why, say, Holmes-a-Court couldn't revamp a few classic US series for ITV. Perhaps adapt some of Turner's IP and then syndicate it on TBS?

Any ideas? It'd likely need to be something small and niche (not Star Wars or Trek) but still beloved due to the economic reasons. Flash Gordon or Battlestar Galactica as a Blitz narrative? Gunsmoke or Little House on the Prairie relocated to colonial Africa in the 1880s (ideally without overly romanticizing it)? The Andy Griffith Show set in the Midlands?

County not country.something with a country magistrate?

I imagine that the British Battlestar Galactica would compared too much to Blake's 7 if they're taking inspiration from Blake's 7.I'd love to see Battlestar Galactica be adapted for British audiences. Maybe instead of killer robot Cylons, the British would take inspiration from Blake's 7 and implement a totalitarian government as the primary antagonist as the main characters are trying to flee towards a new Earth as their home, carrying a McGuffin that both parties need.

Why not the 1960s?Not sure when you'd set a British Happy Days, the 50s weren't the 'happy time' it was the Americas so I would advise against a direct swap. You could do it in the 20s or 30s before the Depression hits.

That hasn't stopped british execs though...Having said that we have plenty of shows without having to reset American ones imho.

True though we tend to import rather than wholesale rip off as I understand.That hasn't stopped british execs though...

I think Bonanza could work in Australia with a co-production between the Brits and Aussies.- Little House on the Praire...damn if i don't liked that show, but my grandma loved (with the BIG VALLEY) so i was more or less 'forced' to watch it

country magistrate as in a magistrate located in the country, a rural magistrate

County not country.

Fair point, but I think British audiences would like the change compared to the Cylons, who are pretty simplistic villains in their original incarnation compared to the 2004 reboot. Alternatively, maybe the British adaptation would give the Cylons more development and a more complex reasoning why they would rebel (maybe the Cylons were created by humanity like in the reboot and they destroyed the colonies for their own freedom from their human masters).I imagine that the British Battlestar Galactica would compared too much to Blake's 7 if they're taking inspiration from Blake's 7.

The latter might be a more realistic approach compared to just taking obvious cues from Blake's 7.

Alternatively, the Cylons might have been created as a weapon of war (doesn't really matter against what) and were long thought either all destroyed or safely deactivated/locked away. Sadly a few Basestars were still active out there and by the time they had rebuilt their forces to 'win the war' the colonies no longer registered as the side they were fighting for, so were labeled 'the enemy' and thus the war resumed.maybe the Cylons were created by humanity like in the reboot and they destroyed the colonies for their own freedom from their human masters

I like this version since it mixes up the relationship between the Cylons and humans. Instead of the 'we treated robots bad, so they mad about it' angle of the original (and a lot of scifi, really) and replacing it with 'the Cylons are doing exactly what they were made to do, they simply no longer recognize us as the ones they are supposed to protect', you can make the nuclear allusion or concerns about automation without relying on 'spontaneous hostility from sufficiently complex machines, because thematic reasons'.

Cylon's being the Colonials creation was a huge turn in the 2004 reimagining, in the original 1978 series which I assume will be the one being remade by the Brits the Cylon's were completely alien and their hardon for killing humans came from the Colonials illogical decision to help out another race that was under attack by the Cylons. Since humans acted illogically they were unpredictable and couldn't be trusted to exist ... also Count Ilbis is a dick and wanted to mess with the Lords of Kobols by killing off their chosen people maybe.

Last edited:

Oh really? I didn't know that. Mind, I've never seen the original series (nor more than clips from the 2004 version), I've always assumed Cylons were human-made.Cylon's being the Colonials creation was a huge turn in the 2004 reimagining, in the original 1978 series which I assume will be the one being remade by the Brits the Cylon's were completely alien and their hardon for killing humans came from the Colonials illogical decision to help out another race that was under attack by the Cylons. Since humans acted illogically they were unpredictable and couldn't be trusted to exist ... also Count Ilbis is a dick and wanted to mess with God by killing off his chosen people maybe.

Neat to hear they're alien in origin. That raises the potential to make them scarier, in an eldritch horror sort of way. We know not their origins, we know not their purpose other than the extinction of human life, they cannot be reasoned or bargained with, that sort of thing.

Oh really? I didn't know that. Mind, I've never seen the original series (nor more than clips from the 2004 version), I've always assumed Cylons were human-made.

Neat to hear they're alien in origin. That raises the potential to make them scarier, in an eldritch horror sort of way. We know not their origins, we know not their purpose other than the extinction of human life, they cannot be reasoned or bargained with, that sort of thing.

Cylons (TOS) - Battlestar Wiki

Ah, well there ya go.Cylons (TOS) - Battlestar Wiki

en.battlestarwikiclone.org

Yeah, if BSG gets a UK adaptation I'd make them even more alien with the simple expedient of never peeking 'behind the curtain' so you only see the Cylons from the humans' perspective for at least the whole first season, where they're an unknowable, existential threat that kills humans on sight without negotiation or declaration of intent.

Only later, perhaps in an event covertly witnessed by human characters do we see any Cylon of higher rank than the Command Centurions, perhaps engaging in diplomacy (the shock!) with another alien species, which just highlights the question why the Cylons are so hellbent on exterminating humans.

That's also a pretty valid take on the Cylons. Playing up on the alien origins of the villains and making them a cosmic horror akin to Lovecraft would make them far more intimidating and terrifying, which would be fitting for British sci-fi to be honest. I like it.Oh really? I didn't know that. Mind, I've never seen the original series (nor more than clips from the 2004 version), I've always assumed Cylons were human-made.

Neat to hear they're alien in origin. That raises the potential to make them scarier, in an eldritch horror sort of way. We know not their origins, we know not their purpose other than the extinction of human life, they cannot be reasoned or bargained with, that sort of thing.

The question is how would any British network like ITV acquire the rights of BSG or if there was any interest at all in acquiring the rights in the late 80s or early 90s.

Hmmm... ... ... What about Kolchak the Night Stalker, set in 1980s London? I know it was a raitings bomb, but Darren McGavin is still recognizable enough that a British remake of his show might be noteworthy ITTL...Any ideas? It'd likely need to be something small and niche (not Star Wars or Trek) but still beloved due to the economic reasons. Flash Gordon or Battlestar Galactica as a Blitz narrative? Gunsmoke or Little House on the Prairie relocated to colonial Africa in the 1880s (ideally without overly romanticizing it)? The Andy Griffith Show set in the Midlands?

The only other idea that immediately jumps out to me is a British remake of an anthology series, like Twilight Zone or Tales from the Darkside.

Last edited:

Non-Disney Animation II

Chapter 12: New Beginnings and Long Anticipated Returns

From In the Shadow of the Mouse, Non-Disney Animation 1960-2000, by Joshua Ben Jordan

As the 1980s came to an end, the Golden Age of merchandise-driven TV animation began to wane. Audiences for franchises like He Man, Care Bears, GI Joe, Transformers, and My Little Pony began to grow up and move on. Only the brand new Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were building an audience. Meanwhile, “lock-out” of new fans to the old franchises due to market saturation of toys began to set in, leaving potential second wave fans feeling “left behind” and not willing to commit[1]. This came right on the heels of a massive shift in the economics of animation.

In 1985 only Disney made near exclusive use of in-house animation, putting them at a financial disadvantage compared to the cheaper largely Asian-made “runaway production” used by the competing studios. Several studios predicted that Disney TV animation would collapse upon itself. By 1988, however, the situation had reversed. The Yen had increased in value 40% against the dollar since 1984 and the cost of living and wages in Japan were increasing steadily. Companies like Sunbow scrambled to find newer, cheaper studios willing to accept US dollars directly, often in Taiwan or South Korea. While these upstart studios would eventually master the craft, the early learning curves were steep and the quality suffered. Suddenly, the costs to produce an episode of Muppet Babies and an episode of My Little Pony were on par, but the quality of the latter was even worse than before. And despite the assumptions of most studios, quality mattered, even to children, who would get upset when Duke’s hair color inexplicably changed from scene to scene. Meanwhile, even a small but growing number of adults were watching some of the Disney cartoons, whose clever writing and multidimensional characters resonated beyond the target audience.

And Disney had an ace up its sleeve: computers. For most of the 1980s computer animation remained an expensive novelty. But by 1988 Disney’s investments, beginning with the DATA machines and then perfected through the Disney Imagination Station and CHERNABOG mainframe during the production of Where the Wild Things Are, were bearing fruit. Using computer-mapped layouts and computer-generated backgrounds had all but eliminated the need for hand-drawing new backgrounds and layering cels on a multiplane frame. All of the upfront costs of building up the library of digital backgrounds was now resulting in drastically lower per-frame costs as animators tapped that library. Combined with the sudden reversal in the economics of runaway production, Disney was now producing animation at near equivalent costs to their lower quality competitors. Disney TV Animation was here to stay.

Furthermore, consumer trends were changing. Complaints were increasing from parents’ groups and educators about the violence and lack of meaningful educational or social value in many of the merch-driven shows. More and more parents and teachers were being more and more deliberate about what their children watched and were selecting products for their kids that had more “redeeming value”. You knew an episode of Muppet Babies or Duck, Duck, Goof would have very few if any weapons, but would have lots of valuable life’s lessons on forgiveness and emotional connection embedded into the plot. You couldn’t say the same about GI Joe, whose problems were inevitably solved through an explosion or punch to the face and whose “educational content” rarely exceeded a 20-second PSA-clip before the final credits[2].

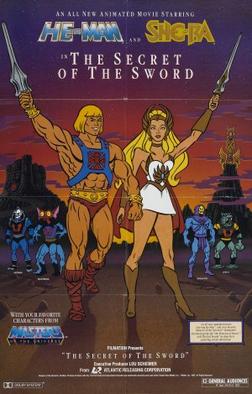

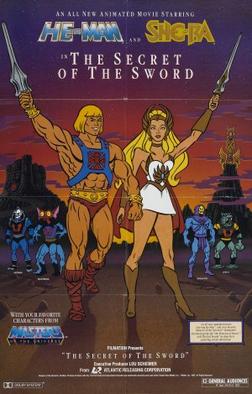

But even as the merch-driven cartoons slowly waned on TV, they still maintained a strong position on the big screen. For most of the 1980s, non-Disney feature animation in the US consisted largely of feature length versions of TV animation aimed exclusively at an existing audience. Animated movie versions of The Care Bears, The Littles, The Smurfs, Alvin and the Chipmunks, Transformers, GI Joe, My Little Pony, He Man/She Ra, and Thundercats[3], all featuring the limited animation and simplistic plots of their television incarnations, appeared on the big screen from 1983 to 1989. They cost very little to produce, underwhelmed anyone outside of their target audience, and generally made marginal profits, if any (The Care Bears Movie of 1985 was a notable exception, making a surprising $34 million against a paltry $2 million budget). The movies thus served more and more as expensive advertising than as any real attempt to turn an immediate theatrical profit.

But the low quality was catching up to them and parent’s groups protested the shameless consumerism and serious violence of the movies, which was often worse than on the TV series. Transformers: The Movie was particularly egregious, with dozens of characters dying, including the beloved hero Optimus Prime. Even the emerging favorites were eschewing the “90-minute commercial” approach. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, for example, decided to pursue a live action film, marking the end of an era.

The major exceptions to the TV-driven rule on the US big screen were the aforementioned Howard the Duck and The Thief and the Cobbler, as well as Japanese anime features, which, following the example of Disney’s partnership with Studio Ghibli, were starting to see distribution in the US. These latter movies included the neo-noir Wicked City, the ludicrously violent Fist of the North Star, and the cyberpunk thriller Akira, all distributed from 1987 to 1989 in the US by Image Entertainment[4] in partnership with Universal. This also included Yutaka Fujioka’s decades-long project Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland, released in 1989. The Japanese releases each generally made a few million dollars in the US, providing Image in particular with a modest profit. They also sold well on VHS to a growing niche audience. The visually stunning Akira would find an appreciative American audience, making a good $19 million in wide release in theaters, built on strong word of mouth, and more than $40 million in video sales and rentals, becoming a beloved cult classic[5].

The modest success of anime in America even encouraged Henry G. Saperstein of United Productions of America (UPA) to finalize a deal with Japan’s Toho for a fully animated Godzilla movie[6]. The classic animation studio partnered with Toho to produce a 90-minute animated film, released in 1988. The film was distributed through Universal, which in addition to its Anime forays was testing the waters on kaiju with the hope of potentially resurrecting King Kong in animated form as a possible tie-in to their King Kong Encounter ride in Universal Studios in Hollywood, with a second secretly being planned for Universal Studios, Orlando. The film garnered good reviews and made a modest profit thanks to a modest US attendance, and it played well in Japan and Asia. VHS sales in America distributed via UPA and Universal managed to build on the cult Godzilla brand in the US.

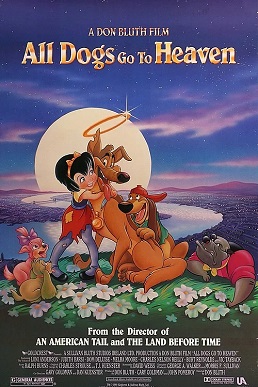

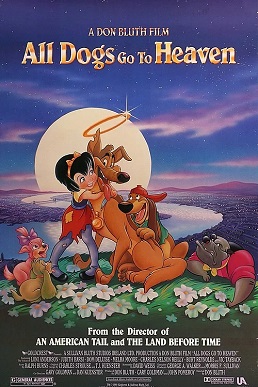

With the completion of The Thief and the Cobbler, meanwhile, Don Bluth was free to pursue his own projects again. Word got around that he and his team had played a critical role in keeping the ambitious picture on schedule and to some degree within budget. As such, finding willing investors for his new project, the Burt Reynolds and Judith Barsi helmed All Dogs Go to Heaven, a concept which he’d been mulling over since the days of The Secret of NIMH, became easier than it might have otherwise. Bluth and his team stayed in Ireland, setting up shop in Dublin where costs were low but talent high (many of Williams’s former animators stayed on with Bluth after Williams went into semi-retirement). UK-based Goldcrest Films and ACC teamed up to provide funds for the film. With studio backing and an experienced team, who had learned quite a lot from their days working on The Thief and the Cobbler, Bluth was confident that he’d soon be in position to challenge his former bosses at Disney itself.

Bakshi-Kricfalusi Productions[7], meanwhile, had begun production on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, with animation aping the style of the original Ralph Steadman drawings. Steadman himself served as a consultant, as did Hunter S. Thompson to a degree. “Thompson was either the most fun guy in the room or an absolute lunatic nightmare depending on what combination of substances he was on at the time,” recalled Bakshi. “But either way you couldn’t trust in the accuracy of a single thing that he said, which honestly worked fine for the production.” Getting off the ground proved problematic, as the ex-girlfriend that Thompson had gifted with the movie rights wanted to do a live action version of the book, having a low opinion of animation. “It took the combined lobbying of George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and Hunter himself, plus all but forcing her to watch Coonskin and Howard the Duck in its uncut form, to get her to relent,” recalled Kricfalusi. The film was executive-produced by Martin Scorsese[8] and distributed by Universal, with voice work by Bill Murray reprising his Where the Buffalo Roam role as the Thompson-expy “Raoul Duke” and Cheech Marin as the Oscar Acosta-expy “Dr. Gonzo”. It would ultimately premier in 1989[9].

As a rule, though, feature animation belonged to Disney throughout the 1980s. While it seems amazing in hindsight, none of the major studios were willing to get involved in feature animation save for Disney. Even the breakout success of Where the Wild Things Are did little to persuade the studio heads to “gamble” on animation. Most analysts of the time concluded that Wild Things was a one-time fluke built out of the general zeitgeist of the mid-1980s and the Boomers sharing nostalgia with their kids. Most predicted that Disney’s upcoming A Small World with its girl protagonist and basis in a 40-year-old children’s novel would be dead-on-arrival. Some studios like Warner Brothers, long since having abandoned even its “composite features”, decided to take a wait-and-see approach with the upcoming Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which was about to return Bugs & Daffy to the big screen, albeit only in cameos. Assuming the movie did well, perhaps they’d revisit the issue.

The past…but what is the future? (Image sources Wikimedia and Amazon)

One major exception in this regard was ABC, or more specifically their Hollywood Pictures subsidiary led by Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg. Eisner made a deal with DIC Entertainment to return The Littles to the big screen. While their original big screen venture, We Are the Littles, had performed poorly and the sequel Liberty and the Littles had gone straight to television, Eisner let them know that he had faith in the franchise. In reality, he had Disney in his sights. After missing the opportunity to take over Disney in 1984, Eisner saw The Littles as exactly the weapon to wield against the perfidious Mouse. Specifically, he saw a new Littles movie as a way to undercut A Small World since the 1960s-era Littles franchise bore a more than passing resemblance in concept to the secret Lilliputian world in Mistress Masham’s Repose.

It wouldn’t be the last dualling, or indeed dueling, movie in the works.

[1] When there’s no real hope of ever collecting the full set (“gotta get ‘em all!”), then it’s harder for a new potential customer to get into a toy line.

[2] And knowing is half the battle.

[3] Disney has demonstrated that there’s a market for feature animation. As such, the Sunbows of the world have more enthusiastically jumped on the “feature length TV episode” format. If you’re wondering what the Thundercats movie is like, well, watch the original cartoon and expand that to 90 minutes.

[4] In our timeline most went straight to video in the ‘80s or didn’t appear in the US until the 1990s.

[5] In our timeline Akira like almost all 1980’s anime came late to the US and received only a limited release. Here Disney’s example with Studio Ghibli has gotten it a wider release, making a roughly equivalent gross to the earlier Studio Ghibli releases.

[6] Yet another hat-tip to @nick_crenshaw82. I’d forgotten that UPA was still in business at this point!

[7] Known to its fans and detractors alike as “Bat-Shit Productions”.

[8] Scorsese tried unsuccessfully to produce Fear and Loathing in our timeline too.

[9] With BKP busy making this movie they will not have the chance to bamboozle CBS into thinking that they have the rights to Mighty Mouse (which belong to WB in this timeline but ironically belonged to CBS in ours), meaning that Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures is effectively butterflied in this timeline, at least as we know it. WB will relaunch a Mighty Mouse series in the late ‘80s, but it will be animated inhouse. This also means no “cocaine snorting scene” controversy with the American Family Association (MM was actually sniffing shattered flower petals) causing the series to get cancelled early.

From In the Shadow of the Mouse, Non-Disney Animation 1960-2000, by Joshua Ben Jordan

As the 1980s came to an end, the Golden Age of merchandise-driven TV animation began to wane. Audiences for franchises like He Man, Care Bears, GI Joe, Transformers, and My Little Pony began to grow up and move on. Only the brand new Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles were building an audience. Meanwhile, “lock-out” of new fans to the old franchises due to market saturation of toys began to set in, leaving potential second wave fans feeling “left behind” and not willing to commit[1]. This came right on the heels of a massive shift in the economics of animation.

In 1985 only Disney made near exclusive use of in-house animation, putting them at a financial disadvantage compared to the cheaper largely Asian-made “runaway production” used by the competing studios. Several studios predicted that Disney TV animation would collapse upon itself. By 1988, however, the situation had reversed. The Yen had increased in value 40% against the dollar since 1984 and the cost of living and wages in Japan were increasing steadily. Companies like Sunbow scrambled to find newer, cheaper studios willing to accept US dollars directly, often in Taiwan or South Korea. While these upstart studios would eventually master the craft, the early learning curves were steep and the quality suffered. Suddenly, the costs to produce an episode of Muppet Babies and an episode of My Little Pony were on par, but the quality of the latter was even worse than before. And despite the assumptions of most studios, quality mattered, even to children, who would get upset when Duke’s hair color inexplicably changed from scene to scene. Meanwhile, even a small but growing number of adults were watching some of the Disney cartoons, whose clever writing and multidimensional characters resonated beyond the target audience.

And Disney had an ace up its sleeve: computers. For most of the 1980s computer animation remained an expensive novelty. But by 1988 Disney’s investments, beginning with the DATA machines and then perfected through the Disney Imagination Station and CHERNABOG mainframe during the production of Where the Wild Things Are, were bearing fruit. Using computer-mapped layouts and computer-generated backgrounds had all but eliminated the need for hand-drawing new backgrounds and layering cels on a multiplane frame. All of the upfront costs of building up the library of digital backgrounds was now resulting in drastically lower per-frame costs as animators tapped that library. Combined with the sudden reversal in the economics of runaway production, Disney was now producing animation at near equivalent costs to their lower quality competitors. Disney TV Animation was here to stay.

Furthermore, consumer trends were changing. Complaints were increasing from parents’ groups and educators about the violence and lack of meaningful educational or social value in many of the merch-driven shows. More and more parents and teachers were being more and more deliberate about what their children watched and were selecting products for their kids that had more “redeeming value”. You knew an episode of Muppet Babies or Duck, Duck, Goof would have very few if any weapons, but would have lots of valuable life’s lessons on forgiveness and emotional connection embedded into the plot. You couldn’t say the same about GI Joe, whose problems were inevitably solved through an explosion or punch to the face and whose “educational content” rarely exceeded a 20-second PSA-clip before the final credits[2].

But even as the merch-driven cartoons slowly waned on TV, they still maintained a strong position on the big screen. For most of the 1980s, non-Disney feature animation in the US consisted largely of feature length versions of TV animation aimed exclusively at an existing audience. Animated movie versions of The Care Bears, The Littles, The Smurfs, Alvin and the Chipmunks, Transformers, GI Joe, My Little Pony, He Man/She Ra, and Thundercats[3], all featuring the limited animation and simplistic plots of their television incarnations, appeared on the big screen from 1983 to 1989. They cost very little to produce, underwhelmed anyone outside of their target audience, and generally made marginal profits, if any (The Care Bears Movie of 1985 was a notable exception, making a surprising $34 million against a paltry $2 million budget). The movies thus served more and more as expensive advertising than as any real attempt to turn an immediate theatrical profit.

But the low quality was catching up to them and parent’s groups protested the shameless consumerism and serious violence of the movies, which was often worse than on the TV series. Transformers: The Movie was particularly egregious, with dozens of characters dying, including the beloved hero Optimus Prime. Even the emerging favorites were eschewing the “90-minute commercial” approach. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, for example, decided to pursue a live action film, marking the end of an era.

The major exceptions to the TV-driven rule on the US big screen were the aforementioned Howard the Duck and The Thief and the Cobbler, as well as Japanese anime features, which, following the example of Disney’s partnership with Studio Ghibli, were starting to see distribution in the US. These latter movies included the neo-noir Wicked City, the ludicrously violent Fist of the North Star, and the cyberpunk thriller Akira, all distributed from 1987 to 1989 in the US by Image Entertainment[4] in partnership with Universal. This also included Yutaka Fujioka’s decades-long project Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland, released in 1989. The Japanese releases each generally made a few million dollars in the US, providing Image in particular with a modest profit. They also sold well on VHS to a growing niche audience. The visually stunning Akira would find an appreciative American audience, making a good $19 million in wide release in theaters, built on strong word of mouth, and more than $40 million in video sales and rentals, becoming a beloved cult classic[5].

The modest success of anime in America even encouraged Henry G. Saperstein of United Productions of America (UPA) to finalize a deal with Japan’s Toho for a fully animated Godzilla movie[6]. The classic animation studio partnered with Toho to produce a 90-minute animated film, released in 1988. The film was distributed through Universal, which in addition to its Anime forays was testing the waters on kaiju with the hope of potentially resurrecting King Kong in animated form as a possible tie-in to their King Kong Encounter ride in Universal Studios in Hollywood, with a second secretly being planned for Universal Studios, Orlando. The film garnered good reviews and made a modest profit thanks to a modest US attendance, and it played well in Japan and Asia. VHS sales in America distributed via UPA and Universal managed to build on the cult Godzilla brand in the US.

With the completion of The Thief and the Cobbler, meanwhile, Don Bluth was free to pursue his own projects again. Word got around that he and his team had played a critical role in keeping the ambitious picture on schedule and to some degree within budget. As such, finding willing investors for his new project, the Burt Reynolds and Judith Barsi helmed All Dogs Go to Heaven, a concept which he’d been mulling over since the days of The Secret of NIMH, became easier than it might have otherwise. Bluth and his team stayed in Ireland, setting up shop in Dublin where costs were low but talent high (many of Williams’s former animators stayed on with Bluth after Williams went into semi-retirement). UK-based Goldcrest Films and ACC teamed up to provide funds for the film. With studio backing and an experienced team, who had learned quite a lot from their days working on The Thief and the Cobbler, Bluth was confident that he’d soon be in position to challenge his former bosses at Disney itself.

Bakshi-Kricfalusi Productions[7], meanwhile, had begun production on Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, with animation aping the style of the original Ralph Steadman drawings. Steadman himself served as a consultant, as did Hunter S. Thompson to a degree. “Thompson was either the most fun guy in the room or an absolute lunatic nightmare depending on what combination of substances he was on at the time,” recalled Bakshi. “But either way you couldn’t trust in the accuracy of a single thing that he said, which honestly worked fine for the production.” Getting off the ground proved problematic, as the ex-girlfriend that Thompson had gifted with the movie rights wanted to do a live action version of the book, having a low opinion of animation. “It took the combined lobbying of George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and Hunter himself, plus all but forcing her to watch Coonskin and Howard the Duck in its uncut form, to get her to relent,” recalled Kricfalusi. The film was executive-produced by Martin Scorsese[8] and distributed by Universal, with voice work by Bill Murray reprising his Where the Buffalo Roam role as the Thompson-expy “Raoul Duke” and Cheech Marin as the Oscar Acosta-expy “Dr. Gonzo”. It would ultimately premier in 1989[9].

As a rule, though, feature animation belonged to Disney throughout the 1980s. While it seems amazing in hindsight, none of the major studios were willing to get involved in feature animation save for Disney. Even the breakout success of Where the Wild Things Are did little to persuade the studio heads to “gamble” on animation. Most analysts of the time concluded that Wild Things was a one-time fluke built out of the general zeitgeist of the mid-1980s and the Boomers sharing nostalgia with their kids. Most predicted that Disney’s upcoming A Small World with its girl protagonist and basis in a 40-year-old children’s novel would be dead-on-arrival. Some studios like Warner Brothers, long since having abandoned even its “composite features”, decided to take a wait-and-see approach with the upcoming Who Framed Roger Rabbit, which was about to return Bugs & Daffy to the big screen, albeit only in cameos. Assuming the movie did well, perhaps they’d revisit the issue.

The past…but what is the future? (Image sources Wikimedia and Amazon)

One major exception in this regard was ABC, or more specifically their Hollywood Pictures subsidiary led by Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg. Eisner made a deal with DIC Entertainment to return The Littles to the big screen. While their original big screen venture, We Are the Littles, had performed poorly and the sequel Liberty and the Littles had gone straight to television, Eisner let them know that he had faith in the franchise. In reality, he had Disney in his sights. After missing the opportunity to take over Disney in 1984, Eisner saw The Littles as exactly the weapon to wield against the perfidious Mouse. Specifically, he saw a new Littles movie as a way to undercut A Small World since the 1960s-era Littles franchise bore a more than passing resemblance in concept to the secret Lilliputian world in Mistress Masham’s Repose.

It wouldn’t be the last dualling, or indeed dueling, movie in the works.

[1] When there’s no real hope of ever collecting the full set (“gotta get ‘em all!”), then it’s harder for a new potential customer to get into a toy line.

[2] And knowing is half the battle.

[3] Disney has demonstrated that there’s a market for feature animation. As such, the Sunbows of the world have more enthusiastically jumped on the “feature length TV episode” format. If you’re wondering what the Thundercats movie is like, well, watch the original cartoon and expand that to 90 minutes.

[4] In our timeline most went straight to video in the ‘80s or didn’t appear in the US until the 1990s.

[5] In our timeline Akira like almost all 1980’s anime came late to the US and received only a limited release. Here Disney’s example with Studio Ghibli has gotten it a wider release, making a roughly equivalent gross to the earlier Studio Ghibli releases.

[6] Yet another hat-tip to @nick_crenshaw82. I’d forgotten that UPA was still in business at this point!

[7] Known to its fans and detractors alike as “Bat-Shit Productions”.

[8] Scorsese tried unsuccessfully to produce Fear and Loathing in our timeline too.

[9] With BKP busy making this movie they will not have the chance to bamboozle CBS into thinking that they have the rights to Mighty Mouse (which belong to WB in this timeline but ironically belonged to CBS in ours), meaning that Mighty Mouse: The New Adventures is effectively butterflied in this timeline, at least as we know it. WB will relaunch a Mighty Mouse series in the late ‘80s, but it will be animated inhouse. This also means no “cocaine snorting scene” controversy with the American Family Association (MM was actually sniffing shattered flower petals) causing the series to get cancelled early.

actually an episode in BSG 80 looked at that.Neat to hear they're alien in origin. That raises the potential to make them scarier, in an eldritch horror sort of way. We know not their origins, we know not their purpose other than the extinction of human life, they cannot be reasoned or bargained with, that sort of thing.

in the episode the return of starbuck, he is stuck with a cylon on a planet, and they get to a mutual understanding

The Return of Starbuck - Battlestar Wiki

Oh, this definitely deserves its own post,The modest success of anime in America even encouraged Henry G. Saperstein of United Productions of America (UPA) to finalize a deal with Japan’s Toho for a fully animated Godzilla movie[6]. The classic animation studio partnered with Toho to produce a 90-minute animated film, released in 1988. The film was distributed through Universal, which in addition to its Anime forays was testing the waters on kaiju with the hope of potentially resurrecting King Kong in animated form as a possible tie-in to their King Kong Encounter ride in Universal Studios in Hollywood, with a second secretly being planned for Universal Studios, Orlando. The film garnered good reviews and made a modest profit thanks to a modest US attendance, and it played well in Japan and Asia. VHS sales in America distributed via UPA and Universal managed to build on the cult Godzilla brand in the US.

Also, I still directly blame Reagan's deregulation of every industry era for the violent toy commercials that apparently were bad for kids. I hope these groups turn their ire to him and the Republicans rather then the cartoons.

Wonder if TMNT movie franchise will avoid their ire too. Maybe if the studio bribes them, or there's a scene where the characters discuss violence (maybe Spliter castigates the Turtles after a prank gone wrong?) and how violence in the screen is not the same as those of real life; or alternatively, there's a disclaimer before the movie where the turtles tell the audience "Don't try any of what we do in real life. You could get hurt or someone hurt, especially since you aren't mutants or turtles like us".

Last edited:

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: