European Crossroads

King Alfonso XIII of Spain

Integralism, Irredentism and Illegality

Since the loss of its colonial empire in the Spanish-American War at the dawn of the century, Spain had sought any and every avenue they could imagine to return to a position of prominence. This had eventually led to an almost mad focus on Morocco just as the rest of Europe turned their eyes to the same region. While they had won a series of campaigns against the tribal peoples of the Rif region in northern Morocco and eventually split the remainder of the Sultanate with the French, it had been far from an easy endeavour, with the blood and gold spilt in the effort provoking labor unrest and violence, which in 1909 had culminated in a revolt out of Barcelona and an attempted General Strike, both of which had ended in tragedy. In the aftermath of the 1909 crisis, the long-time Prime Minister Antonio Maura fell from power in favour of a short liberal government chiefly focused on anti-clerical measures, which was soon replaced by a conservative government led by Eduardo Dato and backed by Maura, the two conservative voices who would dominate the coalition governments of the Great War years. The chaos which followed the end of the Great War would severely weaken the status quo, particularly following the assassination of Eduardo Dato in 1922.

However, at around this point in time the situation in Morocco were rapidly collapsing as Rif rebels under the leadership of Abd el-Krim attacked Spanish forces after they crossed into un-occupied Rif territory in pursuit of a local bandit warlord by the name of Mulai Ahmed er Raisuni, seeking to establish an independent Rif Republic. Whipping up a furor amongst the Riffans, el-Krim attacked an outpost defending a large military encampment at Annual, resulting in 141 Spanish casualties and resulting in a rush of support for el-Krim. Encircling the encampment at Annual, which had grown to number some 4,000 men by July 1921, the commander Manuel Fernandez Silvestre was convinced to retreat when the surrounding 18,000 Rif forces cut the Spanish lines of communication. Departing early in the evening on the 21st of July, Silvestre and his force were able to cross the northern heights with the Riffans on their heels. They encountered reinforcements enroute numbering some 900 but continued their retreat towards the forts of Ben-Tieb and Dar-Drius, skirmishing fiercely with the Riffans all the way. Most notable would be the rearguard action of Fernando Primo de Rivera, who lost nearly half his command, some 300 men, in the fighting but was able to hold the line long enough for the Spanish to reach safety.

At Dar-Drius, the Spanish received significant reinforcements at the orders of High Commissioner Damaso Berenguer numbering nearly an additional 4,000 while as many as 25,000 peninsular forces were prepared for deployment in Spain. The resultant Battle of Dar-Drius was a bitterly fought repulse of the Riffans, which saw the Spanish forced nearly to the brink by the rapid if disordered attacks of the Riffans over the course of a week while raiders penetrated far into Spanish-occupied territory in the process. By early August, troops from Spain had begun to arrive in large numbers and Silvestre was able to shore up the Spanish-occupied positions. The remainder of the year and the next would see little Spanish progress despite considerable investment, with domestic turmoil making steady supply and reinforcement by conscription next to impossible. It was at this time that King Alfonso received a surprising proposal of aid from Portugal, where Sidonio hoped to shore up his neighbor in order to stabilize the porous eastern border wherefrom anarchists and socialists regularly crossed over to hide out or cause havoc in Portugal (1).

In early 1923 the Riffans found themselves the target of a major campaign of suppression as Portuguese and Spanish forces stormed eastward out of Tetuán, sweeping through the region with extreme force, utilizing tactics originally pioneered in the bitter fighting of the Cuban War of Independence. Large camps were established to contain a significant portion of the rebellious population while the irregular fighters of the Rif were forced backwards or into the desert. El-Krim would gamble on a single large battle near the city of Chauen, catching the Iberian forces by surprise, driving them back and successfully cutting off nearly 2,000 men, including the forces of the recently established Spanish Legion, who soon found themselves besieged in the small town of Derdara south of Chauen. Over the course of more than a month, as the Iberian allies reconstructed their scattered forces, the men at Derdara fought of continual assaults with only parachuted supplies to keep them going. Finally, on the 8th of May 1923, the Iberians launched another attack which successfully broke the Riffans' backs and drove them into retreat. The survivors of the Siege of Derdara were feasted and buried in medals while the dead, amongst them the Legionnaire commander Francisco Franco, brother of the activist Spanish politician Ramón Franco, were widely mourned and lionised. Over the remainder of the year Riffan resistance was steadily broken culminating in the public execution of Abd el-Krim late in the year. By mid-1924 Riffan resistance would finally die out and the Spanish would finally secure firm control of the region.

This final success, and the prolonged exposure to the surprisingly stable and successful Sidonist regime, would strengthen the King's hand to a degree not seen in the current century. Rallying support from the military and political traditionalists, most prominently Juan Vásquez de Mella, King Alfonso launched a coup against the current liberal government of Manuel Prieto Garcia on the 20th of January 1924, placing the entire government under arrest and abrogating the current constitution. With the aid of Mella and other Carlists, King Alfonso rewrote the constitution into a far more autocratic form, taking inspiration from the Sidonist regime in Portugal. Having struck with surprise and military backing, the King was able to imprison many of the most significant potential rivals to his power and made a number of key deals with the Catholic Church to gain their backing in this endeavor as well. What disorganized resistance which appeared in response to the coup was crushed firmly with military might even as a swath of new legislation was passed by fiat. Over the course of 1924, the King strengthened his grip on power further and deepened the relationship with the Catholic Church. This would culminate in December when King Alfonso invited the Vatican to set up in the Cathedral city of Santiago de Compostela until Rome could be reconquered. This offer was accepted by Pope Gregory VII, who would spend the next year digging into the city. During this time King Alfonso publicly declared in favor of integralism and further strengthened his grip on power, seeking to turn the Spanish Kingdoms into an absolutist monarchy once more (2).

In Milan, the Central Committee of the Italian Communist Party met the announcement of the Vatican's settling in Santiago de Compostela with barely concealed worry. As a newly formed revolutionary state with few friends in the world, the fact that the Spanish had not only settled their bleeding ulcer in North Africa but had also brought their state to order by implementing a monarchical version of Sidonism, allowing them to engage with the rest of the world presented a significant threat to the Italian State. While supplies of coal and oil were purchasable for the Italians through their German contacts, it came at a significant premium and placed the state at the mercy of the Germans.

Even beyond the threat posed by foreign powers, the internal stability of the new Italian state was none too secure, with immense resources required for reconstruction efforts and a considerable problem with rebels and bandits, particularly in the south, who constantly fought any effort at reform by the thoroughly northern Communist government. While vast noble estates were liquidated and the land parcelled out to the surrounding peasantry, the Italians embarked on a societal reconstruction on a level rarely thought possible in the past. Land lords were dispossessed, church lands were nationalised, corporations were syndicalised, with ownership given over to the factory's workers, while local government was placed under the control of centrally appointed Commissars and regional autonomy was rapidly reduced.

Clashes within the Communist Party between centrist and anarchist factions proved fierce as differences regarding issues as disparate as Italy's role in the spread the revolution and the degree to which power should be focused in a central government or at a regional level caused major divisions. Most significantly, the centrists wished to build a model revolutionary communist state while the anarchists were determined to press on with the revolution. The relationship between anarchist and centrist became increasingly tense as the violent suppression of dissent in southern Italy reached a fever pitch in August of 1926 in the aftermath of the Calitri Massacre, where much of the small south Italian town's population was killed or dispersed after its inhabitants went into violent revolt at the instigation of a local dispossessed noble family.

While military law was imposed across much of the south and governance of the region taken over by direct representatives from the Central Committee, the Calitri Massacre proved the instigating spark in a short-lived but extremely bloody revolt in the Campanian highlands. Sweeping across the province, government representatives were assaulted and on multiple occasions lynched by outraged locals while villagers dug up weapons hidden since the end of the Civil War. Red Army forces were rushed south and soon came into direct contact with the irregular rebel forces, who had already begun receiving supplies from Sicily. While the red Army lost nearly 300 men in the fighting, they would kill in excess of 5,000 in the frenzied response, culminating in the public execution of a dozen prominent regional families whose patriarchs had been integral to the spreading of the revolt. While the centrists were deeply engaged in the pacification of southern Italy, the anarchists established secret training camps in the northern Apennines where they prepared revolutionaries to spread Communism across the world, with representatives from as far-flung regions as Vietnam, Colombia, France and Spain. The discovery of these camps in 1929 by the centrists would ultimately lead to bitter infighting in the Central Committee which culminated in the expulsion of Errico Malatesta from the Central Committee and the closure of the training camps, although by this time more than 1,000 trainees had already gone through training and been dispatched to spread the revolution (3).

In contrast to the isolation experienced by the Italian mainland, the Kingdom of Italy, consisting of Sicily and Sardinia, could barely be more connected to the rest of the world. In an effort to keep their French and British backers on board, the Sicilian government tore down most of its trade barriers, completely opening itself up to economic dominance by the two states. In return, they were able to secure favourable trade deals with both Britain and France and quickly came to serve as a key transshipment point for trade through the Mediterranean. The cities of Palermo and Catania would grow rapidly with this influx of trade even as the Mafia moved from the country-side into these very cities.

Over the course of the latter half of the 1920s, the struggle for control of the Catania and Palermo smuggling routs would provoke bitter conflicts between Mafia clans and saw the rise of new figures to power, most significantly the Greco and Motisi clans in Palermo driving back an effort by the Agrigento-based Cuntrera clan to take control of the city's dockyards and the rise to prominence of the Saitta clan in Catania under Antonio Saitta. Antonio Saitta, emerging outside of the traditional Mafia structures, presented a major threat to Calogero Vizzini's dominance of the Sicilian underworld and soon saw the two clash violently in a series of "Mafia Wars" for control of Catania. Ultimately, Saitta was able to emerge victorious and cement his control of the city, forcing Don Calo to accept his presence.

However, a key reason for Calo's failure to crush Saitta could be found in his increasing involvement in Sicilian politics, where Dino Grandi and his fascist cohorts were rallying support to end Nitti's reign. The challenge here was over the fact that many of Grandi's supporters wished to press the French for the return of Libya to them, which left Don Calo worried that such a move might sever the profitable ties he and his fellow mafiosi were getting rich from. After a secretive meeting with Grandi, Calo decided to throw his support behind the fascist leader, who proceeded to sweep Nitti and his fellow liberals from power in the elections of 1927. The deal struck between Grandi and the Mafia soon became clear when it emerged that Grandi had killed the proposal to petition for Libya's return. While nationalist supporters of the government were outraged at this betrayal, they soon found themselves increasingly locked out of power by Grandi, who turned firmly towards transactional politics and abandoned much of the populist rhetoric which had brought him to power.

It was soon after this that the betrothal of Infanta Beatriz of Spain to Prince Umberto of Italy was announced, soon followed by the signing of a military alliance between the two states. During this time, Dino Grandi found himself increasingly influenced by the Sidonist and Integralist model which had come to dominate Iberia, restoring considerable power and authority to the Catholic Church in Sicily, significantly weakening democratic government and strengthening his own position of power. By the end of the 1920s, Sicily was emerging as a Fascist state under the rule of Dino Grandi in alliance with the Sicilian Mafia.

Footnotes:

(1) The Battle of Annual plays out very differently from OTL. Instead of a military disaster which propels Miguel Primo de Rivera to power, it is instead a successful retreat. The divergence lies in the cutting of communications spurring Silvestre to retreat earlier, meaning that the northern approaches to Annual are clear of Riffan rebels when the Spanish try to cross them. This means that the status quo civilian government remains in place for a bit longer and avoids the rather disastrous de Rivera government. It also puts the Spanish in a better position to combat the Riffans. We also see Sidonio finally turn outward and begin to engage with the surrounding world.

(2) The Portuguese replace the French in aiding Spain against the Riffans with considerable success, in the process bringing the two states closer together and leading to an exchange of ideas. I had King Alfonso take power ITTL because I think under the circumstance, with his support for the African adventure a success and his enemies divided, this would be both possible and in his nature. The initial success of the move comes mostly because Alfonso is so successful in catching his enemies by surprise. His subsequent alliance with the Catholic Church and the Carlists seemed to be a natural follow-on from this. I decided to place the Vatican in Santiago de Compostela because of its religious prominence in Spain and relative distance from anywhere the pope might cause problems for Alfonso. As for why Spain, it seemed like the best possible solution given that France's relationship with the church remains tense and this path allows easier access to Latin America for the Catholic Church.

(3) Things are not proving easy for the Italian Communists who are dealing not only with severe regional divisions but also internal political challenges and foreign threats. The Milanese government is undertaking a range of radical policies, but are doing so from a North Italian perspective, which puts them at odds with the south where landlord economies remain predominant - this is basically the old north-south divide in Italy on steroids. I use anarchist and centrists as factional notices here but understand that this isn't so much an ideological denominator as a factional one. The divides (anarchist/centrist) are more along the lines of outward/inward focus, regionalist/centralist and revolutionary violence/diplomacy than anything else. Important to note, the expulsion of Malatesta royally pisses off those of anarchist persuasion and puts them on a collision course. Finally, it should be mentioned that the Italian Communist Party's ideological framework resembles OTL Communism far more than the Russian version ITTL and despite the anarchist influx it experienced, it is really the statist socialist side of the coin which has come to dominate there. It is autocratic, centralising and inward-looking, in many ways reminiscent of the Soviet Union in the immediate post-Trotsky's expulsion (Malatesta's expulsion, while nowhere near as severe, at least partially mirroring the effect) - there is a central clique of leaders generally in agreement about how to rule but for the time being it is ruled by an oligarchy rather than a dictatorship.

(4) Sidonist-Integralist-Fascism captures another state while the Mafia further cements its hold on the Sicilian economy. It bears mentioning that the Mafia are increasingly entering into legal businesses to complement their criminal enterprises, building business empires wherein their legal and illegal activities are closely linked. Hell, by this point much of the illegal activity they do perpetrate isn't prosecuted. We also see the rise of a power potentially capable of challenging Don Calo's grip on power in Italy in the form of Antonio Saitta - a mafioso who was crushed by the Fascists IOTL and whose grandsons IOTL rose to dominate the Catanian criminal underworld in the 1950s. It bears mentioning that Catania, and much of eastern Sicily with it, was outside of Mafia control for much of the first half of the 1900s and as such Antonio Saitta is basically constructing a different sort of criminal organisation from the traditional western Sicilian Mafia structure, using a much more corporate framework for his organisation with less focus on family loyalty and more on profits. It isn't a family business like the other Mafia clans.

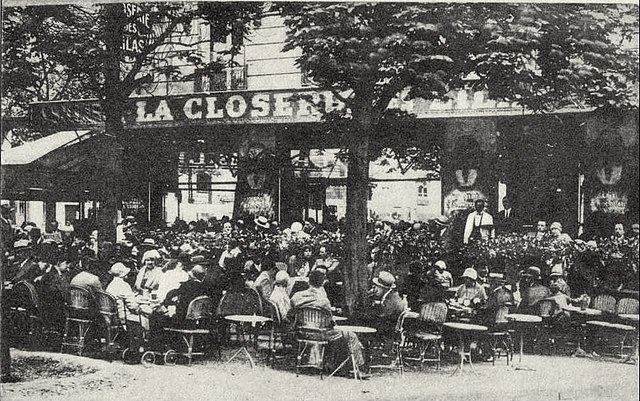

Parisian Cafe Life

The Crazy Years

More than anything else, the middle years of the 1920s in Britain were dominated by the rising power of Labour on the left and growing fears of revolutionary action on the right. Balancing precariously between the radicals in his own party and the cries of Labour demanding major reforms was Austen Chamberlain. Under Chamberlain's careful stewardship, Britain emerged from the economic doldrums of earlier in the decade, rallied by strengthening international exports and a spiking demand for manufactured goods which the British were able to provide in large amounts to trading partners in the Mediterranean, most prominently Sicily, Spain, the Don Whites and the Croatian sub-state of the Habsburg monarchy. Large infrastructure projects, such as the massive Channel Tunnel Project and the modernisation of London's Metro system, and government work programs aided significantly in reducing unemployment further and even helped spark a minor consumption-driven economic boom.

However, none of these efforts proved sufficient to quiet the Labour Party. Rallying against the exclusive nature of the current British Welfare State, being focused almost exclusively on military veterans and their families, Labour pushed for an extension of the unemployment benefits, pensions, healthcare and jobs programs to cover the remaining population. This was accompanied by calls for subsidised low-income rents, decreases in working hours and increased safety standards, particularly in the case of coal mines, where a looming health crisis placed added burden on miner's families. as well as in regards to traffic safety in response to a series of deadly car accidents. Finally, Labour agitated publicly for the restoration of a minimum wage for agricultural workers, greatly increasing their popularity in rural Britain.

Over the course of Austen Chamberlain's ministry, the costs of the Channel Tunnel grew ever greater while the actual work on the project remained sluggish. The matter came to a head in early 1927 when it was discovered that the project had become engulfed in corruption, with much of the state finances dedicated to the project having been swindled away by a combination of contractors, treasury officials, inspectors and several politicians within the Conservative Party. While none of the participants in the corrupt scheme had direct ties to the Prime Minister or any figure on his cabinet, the Tunnel Scandal which resulted from the publication of the corruption would prove deadly to the Chamberlain government. With the public in an uproar and both Labour and the Liberals pouncing at the opportunity to bring down the over-mighty Conservatives, it didn't take long for a vote of no-confidence to reach Parliament. While Chamberlain was able to survive the vote, it severely weakened his government and in October of 1927 led to his resignation - Chamberlain having realised that he had lost the public trust and was unable to continue governing effectively. This resulted in the election of November 1927 in which Labour under Ramsay MacDonald was able to emerge victorious, both the Liberals and Labour having gained from the loss of the Conservatives (5).

The MacDonald Ministry was the first Labour Ministry in British history and was sworn in alongside his Labour cabinet by the King in full court regalia, to the amusement of some and worry of others. The main achievement of the early years of the MacDonald government was that it showed itself to be fit to govern. Although this might not have meant much in terms of concrete policy-making, it at least did not alarm voters who may have feared that the party would dismantle the country and promulgate "Communism"; although, in any case, its tenuous parliamentary position would have made radical moves near impossible. Hence, Labour policies such as nationalization, capital levy taxation and public works programmes to alleviate unemployment were either played down or ignored altogether. However, to act respectably, as any other government would have, was a major component of the MacDonald electoral appeal and strategy.

Despite lacking a parliamentary majority, the Labour Government was able to introduce a number of measures which made life more tolerable for working people. At the same time, the Conservative Party found itself fighting what amounted to a civil war between Unionist and Progressive factions, divided on who should lead the party, whether to ally with the Liberals and what the party's priorities should be. At the heart of this clash were Stanley Baldwin and Lord Robert Cecil, who had until recently sat in Chamberlain's cabinet, and a conflict for leadership of the party in the face of Chamberlain's decision to withdraw from politics. With Labour pushing forward with their reform package and worries about the intentions of the MacDonald government, it was the Unionists, with Baldwin and Joynson-Hicks at their head, who emerged victorious in the struggle, pressing the progressive with into the shadows. Together, Baldwin and Joyson-Hicks led a fierce opposition to the Labour government, which only grew more vocal as MacDonald became bolder.

The shutting down of the Channel Tunnel Project came as an unsurprising blow to the Conservatives, soon followed by concrete Labour policy-initiatives such as the passing of an Act of Parliament in early 1929 which subsidised low-rent housing for the poor, radically strengthened government safety regulations, introducing a powerful regulatory agency in the process, and eventually turned their attention to the expansion of social security. When it became public that MacDonald and his Home Secretary Arthur Henderson would dismantle the Conservative Veterans' Welfare System in favour of a welfare system which would cover the entire population in late 1929, Baldwin and Joyson-Hicks were finally able to muster the support they had been looking for.

A key provision in this new welfare package was that the actual worth of this system was reduced significantly in order to cover so many more people, with the result that war veterans and their close family could expect their benefits to shrink substantially. Veterans groups proved instrumental in the martialling of opposition to the Labour bill which soon engulfed the nation. From north to south, east to west, veterans of the Great War marched through the streets, many wearing their wartime uniforms, medals and other decorations, while publicly excoriating the government. Representatives from the veterans umbrella organisation, The Royal British Legion, petitioned the King to speak out on their behalf while in Parliament itself, veterans amongst the parliamentarians, particularly from the Conservative ranks, spoke out loudly against this change in policy. The further revelation of abuses in the safety regulation administration, accepting bribes from factory and mine owners to ignore violations, further added to the furore culminating in the failure of the administration to secure the requisite votes for the welfare reform bill. The MacDonald government limped on after this occurrence, but was significantly weakened and would struggle to pass legislation for the remainder of the 1920s (6).

The years from 1924 till the end of the decade are known in France as Les Années Folles, the Crazy Years, and can be regarded as a period of significant social, political, cultural and economic flux in which wild new fads, particularly the American Jazz movement, the Charleston, the shimmy, cabarets and nightclub dancing, all rising to prominence in the years that followed as an exodus of broadway stars, jazz musicians, dancers and artists all responded to the growing censorship and nativism of the United States government by seeking out greener pastures, and there were few pastures greener than Paris in the latter half of the 1920s. Paris itself was the beating heart of French leftist movements and a bastion of general progressive intellectual thought. After a period of nostalgia for the Belle Epoque, early in the decade, the 1920s were a period in which powerful new movements of mass culture, consumption and politics all rose to the fore.

Coming just as the most significant reconstruction efforts were brought to an end, France enjoyed an immense economic boom in this period as hydroelectricity investments allowed for an eightfold-increase in electrification, while radio, aviation, automobile and numerous other industrial sectors blossomed. Finishing repairs on the coal mines of northern France allowed for a further economic boom and contributed to the general increase in global coal supply which would with time come to plague the global coal industry. During the early 20th century, the inner eleven arrondissements of Paris became the centers of commerce; their populations were a smaller and smaller share of the total population of the city. About a quarter of Paris workers were engaged in commerce, wholesale and retail. The motors of the city economy were the great department stores, founded in the Belle Époque; Bon Marché, Galeries Lafayette, BHV, Printemps, La Samaritaine, and several others, grouped in the center. They employed tens of thousands of workers, many of them women, and attracted customers from around the world.

The period was a high point for Parisian high fashion with the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in 1925 featuring 72 Parisian fashion designers including Paul Poiret, Jeanne Lanvin, who opened a boutique in 1909 on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, and also branched out into perfume, introducing a fragrance called Arpège in 1927 and the House of Worth, which also introduced perfumes, with bottles designed by René Lalique. New designers challenged the old design houses was challenged, notably Coco Chanel who put her own perfume, Chanel No. 5, on the market in 1920. She introduced the "little black dress" in 1925. Paris was also was the home and meeting place of some of the world's most prominent painters, sculptors, composers, dancers, poets and writers. For those in the arts, it was, as Ernest Hemingway described it, "A moveable feast". Paris offered an exceptional number of galleries, art dealers, and a network of wealthy patrons who offered commissions and held salons. The center of artistic activity shifted from the heights of Montmartre to the neighborhood of Montparnasse, where colonies of artists settled (7).

However, while Paris remained a bastion of progressive thought, it was very much at odds with much of the rest of the country. The Fall of Rome and the exile of the papacy proved immensely, soul-crushingly, devastating to many Catholics in France, with many coming to view the Great War and the expulsion of the Papacy by Communist atheists as a divine call to arms. Popular Catholicism and open displays of religiosity exploded across much of France and soon found itself part of a wider political movement. The active measures taken by the French government to incite the Papacy to depart France were met by great outrage in Catholic circles, who viewed it as a betrayal of the Holy Church, and conspiracy theories ran rampant in right-wing circles, centring primarily on the culpability of the government in covertly supporting the Italian communist regime.

Public calls for an invasion of Italy and the liberation of Rome found surprising levels of support given the recent, tragic, warfare which had engulfed the world. The Ligues were highly politically active, holding demonstrations, marches and protests on a regular basis when they weren't publicly clashing with Communists, Socialists or Anarchists. While in Paris many of these ligues were forced onto the sidelines, in smaller cities like Lyon, Toulouse and Bordeaux they were able to generate considerable support. Support for Catholicism and support for the Republic had long been difficult to square with each other, and as a result this period saw a rather significant increase in support for the various monarchist factions.

However, a pair of deaths in 1926 would significantly ease the challenge of finding a faction to rally behind when Victor Napoleon Bonaparte and Philippe d'Orléans both died, Victor Napoléon Bonaparte in London and Philippe d'Orléans in Palermo. The issue was that Victor Napoléon's death left the Bonapartists without any effective claimant - Victor Napoleon's only son Louis having died in the final year of the Great War from a childhood malady, his brother Louis having died in the chaos of the Russian Revolution and the last branch of the family living in America refusing to take any role, and the Orléanists supporting Jean d'Orléans, the Duke of Guise. The Legitimist candidate, Jaime de Bórbon, was more interested in contesting his cousin, the King of Spain's, claim to the Spanish throne and the Legitimists with few French supporters in general.

In a move which shocked monarchist society, Jean d'Orléans extended a hand of friendship to the Bonarpartists, arranging the betrothal of his son Henri to the four-year-younger Marie Clotilde Bonarparte, Victor Napoleon's sole surviving child. This marked the effective unification of the Bonarpartists with the Orléanists, although an extremely small fringe of Bonapartists would continue to clamor for the American Bonapartes to take up the claim. With the quiet assent of the Pope, Jean d'Orléans proved willing to work with the new far-right factions, foremost among them Action Francaise, and quickly proved an energetic promoter of the monarchist movement. With the success of Integralist and Sidonist models in Iberia and Sicily, the French right soon began to find itself pressed into supporting the catholic-nationalist integralist-monarchist model of Action Francaise, other movements finding themselves either absorbed or crushed, one by one, over the course of the late 1920s and early 1930s (8).

Footnotes:

(5) While Austen Chamberlain's time as Prime Minister during the 1920s was relatively short, it will be remembered quite fondly as a time of prosperity and a return to peace. There remains considerable public backing for Chamberlain and there are many who are sad to see him go, but not only has the office aged him considerably, he also views the Tunnel Scandal to have been a personal failing and a blemish on his honour. It is important to note that while there was considerable labour turmoil, it never quite peaks with a General Strike as happened IOTL. Instead, Labour was able to press ever more heavily against the Conservative position and exploited a moment of weakness to push itself to the top.

(6) The Labour Party gets its first opportunity at governing, but find their efforts collapsing within two years after they took one too many chances. It is important to note that the Labour Party did not in any way change their position towards the Communist regimes in Italy and Russia, regarding both with hostility and suspicion, while the Labour Party was actually forced to suppress some of its more radical supporters within the party to avoid triggering a conflict. While Labour rule has lost some of its immediate shine, the most important thing to note is that the Labour Party has been admitted into the sphere of acceptable parties. With the Conservatives retaining, and even strengthening, their Unionist and Nationalist credentials while weakening their progressive wing, the Liberals are able to exploit the opening which has emerged between the right-wing of the Labour Party and left-wing of the Conservative Party.

(7) This section isn't too far off OTL, but the following section should highlight the major differences between OTL and TTL. France is recovering well and expanding economically, even if not quite as strongly as Germany, with a relatively moderate and competent government running things. It will take a lot more for France to lose its status as Europe's cultural capital. One thing to note is that Les Années Folles is used in a broader context ITTL than IOTL and also covers the political developments of the period in contrast to the largely cultural focus the expression has IOTL.

(8) This is where the French monarchist wing enters the picture, consolidating claims and taking inspiration from movements elsewhere. The disruption in Belgium at the end of the Great War is where things really diverge for the monarchist movement with the death of the last real Bonapartist claimant. I know that having the Bonapartists and Orléanists kiss and make up might be a bit on the implausible end, and arguably the Orléanist investment in this effort might be slightly more than would ordinarily occur, but I do think it remains within the realm of plausibility. Thus, with the legitimists having lost most of their backing when the title fell to the Carlist Bourbon line and the Bonapartists extinguished, the monarchists are able to consolidate. However, the most significant divergence ITTL is definitely the fact that Pope Gregory XVII gives his sanction to working with Action Francaise - where IOTL the church explicitly forbid any cooperation with the movement. This is the result of a more conservative and activist pope than IOTL.

End Note:

I ended up getting completely caught up in a Chinese period drama (The Story of Yanxi Palace) and binged it for much of the week, surprisingly historically accurate dramatisation of mid-1700s Qing Dynasty, when I wasn't busy with securing an internship, so I ended up with a time crunch here at the end. I did end up finishing this second section, so I can give you guys half an update at this point. It does mean I haven't had a lot of time to proof-read though, so if something jumps out please let me know. This update is really focused on the rise of Integralism and other quasi-fascist or fascist movements, and the contrasting leftwing developments to a lesser degree. This update as a whole is mainly an update on events in Europe - with the next two sections dealing with Central and Eastern Europe respectively. I hope you enjoy it.

EDIT: I have made some changes to this section, most significantly removing any reference to Churchill as being a leading figure in the Conservative Unionists at the time.