You know I never understood why they didn’t build an airport at North Weald? It’s right on the Central Line and the West Anglian from Liverpool Street. Seems like a perfect place. Plus it’s near the Kelvedon Hatch nuclear bunker for quick escapes...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

12:08 - Redux

- Thread starter Devvy

- Start date

Devvy

Donor

You know I never understood why they didn’t build an airport at North Weald? It’s right on the Central Line and the West Anglian from Liverpool Street. Seems like a perfect place. Plus it’s near the Kelvedon Hatch nuclear bunker for quick escapes...

I'd guess it's a combination of too close to London (so little location advantage/disadvantage over Heathrow), the Central Line has always been croweded and probably has had little capacity to support an airport at one end with the large amount of extra capacity required, and that it's just over half the way to Stansted anyway where there is already a commercial airport.

That's great for London but what are its transport links like for the rest of the country? A quick look suggests not all that great, although I could be mistaken, and building it north east of London starts putting it away from the population centres of the country.You know I never understood why they didn’t build an airport at North Weald? It’s right on the Central Line and the West Anglian from Liverpool Street.

My personal choice since discussing it with a couple of people is about 25 miles to the west in the Kings Langley area. That would allow for possible links to the West Coast Main Line, M25, M1, A1 etc. whilst inflicting aircraft noise on the smallest number of people. You'd generally have to make the decision much earlier though before local towns were chosen by the government for expansion which puts it outside this timeline.

1974-NorthEast

Devvy

Donor

1973 - Tyneside Metro

The easily identifiable Metro stations

In the early 1970s, the poor local transport system was identified as one of the main factors holding back the region's economy, and in 1971 a study was commissioned by the recently created Tyneside Passenger Transport Authority into how the transport system could be improved; this study recommended reviving the badly run down former Tyneside Electric network by converting it into an electrified rapid transit system, following the example of Manchester, and including a new underground section to better serve the busy central areas of Newcastle and Gateshead, as it was felt that the existing rail network didn't serve these areas adequately. These plans were approved by the Tyneside Metropolitan Railway Bill which was passed by Parliament in 1973. Around 70% of the funding for the scheme came from a central government grant, with the remainder coming from local sources which would benefit from the scheme.

British Rail also did much to help; the nationalised rail network at the time in the mid 1970s resembled a patient trying to limp his/her way to towards salvation. The East Coast Main Line north of Newcastle had repeatedly been slated for cutting, with ECML expresses terminated at Newcastle, and eliminating Anglo-Scottish services on the historic route. In the end, the route gained a last minute reprieve, although almost all feeder and local routes in the area north of the Tyne were to be eventually handed over to the locally operated network - although BR would retain freight privileges during out-of-hours. The first route, would follow the "Manchester Model" - a short cross-city tunnel connecting converted light rail routes on either side of the city, and would utilise the same general design and rolling stock as Manchester. Funding cuts, now notorious for hitting out-of-London projects, reared their heads at first during the planning when tunnels were further constricted to a diameter similar to London's deep tube lines, although still allowing joint procurement for stock with London.

Construction would start rapidly in 1974, with the new cross-Tyne bridge (later named the "Queen Elizabeth II Bridge" in common with many other bridges in the United Kingdom) quick to begin. Almost instantly, proposals surfaced for expanding the network which had to be tempered quickly by HM Treasury in order to prevent runaway funding. 5 years later, the only major extension was granted; a westfacing junction from Gateshead to the under construction MetroCentre and south side of the Tyne, with services extending to Blyth and Ashington. Funding cuts meant the second set of tunnels running on an east-west axis would be cancelled however, resulting the in the eastern access terminating directly at Central Station. The system opened in 1981, with a ceremony originally meant to include royals, but later downgraded to the Minister of Transport.

Early conceptual designs for the "Tyneside Metro"

By the 1990s, the original 4 coach rolling stock was proving difficult to maintain with the service falling in popularity due to drops in reliability. The units were similar to the evolution of earlier London Underground stock; it had single leaf doors, a similar orange interior and cab design. It also featured headlights that were positioned underneath the train body. However, unlike other tube stock, the the trains destined for the north-east proved to be unreliable, and further soured relations. Electrical generators for lighting the carriages failed often, as did the motors. Boarding of passengers was slow because of the single leaf doors. 2000 would see a reversal of fortunes, with a Government eager to play to it's strongholds outside of London; funding was eventually found for a new batch of trains, fully replacing the older units. Less trains would be needed than they were replacing, due to improved reliability, and capacity would be improved by the new trains stretching the full length of the 100m platforms, with articulated and walk-through coaches to make the best of the available space. The improvement in quality quickly showed as passengers numbers immediately begin to rise again; capacity is once again beginning to strain, particularly during the morning rush hour, whilst the routes were split out in to the "A-B-C" Lines, later retroactively better named using the same starting letters to bring some simplicity to navigating the network.

The revival in fortunes was further enhanced in 2004, when local Government re-organisation in England spurred the proposed reform of metropolitan county councils to form "Regional Councils" (with any overlapping counties retained for historical and ceremonial purposes only). This larger and reformed "upper level" of local government would receive further powers over local transportation, and the greater economies of scale was hoped to allow further expansions of the system. In the North-East, tensions and rivalry between Newcastle, Sunderland & Middlesbrough, or between Northumberland and County Durham made this difficult, and instead the Tyne & Wear transport authority received improved local transport powers, rather then the wide ranging prospects envisaged (*A). Extensions to the north and south, taking advantage of former freight-only branches which were being further downgraded (with freight operations retained at night when Metro operations ceased), with Sunderland and Washington joining the network. This also spurred the name change from "Tyneside Metro", to "North East Metro" - although still almost always just called [the] "Metro".

The last new lines, the Wearside and Peak Lines, were not really new "lines", in that they did not require any new physical tracks laid bar a new junction to allow operations from CLS Interchange towards Sunderland. New rolling stock came from refurbished London Underground stock, yet another cost-cutting measure, as London began to introduce a new batch of trains themselves. The Peak Line was introduced to bust congestion during the morning rush hour, along the northern shore of the Tyne, where further services could not formally be introduced to the entire Circle Line as the central core already operated at it's maximum of 24 trains per hour for the majority of the day. The new route, separated for simplicity on the map, allowed rush hour operations to help serve the stations, using the spare platforms already present at Tynemouth. The Wearside Line was also to alleviate congestion - although from the local roads, where congestion in to and out from Sunderland was rife, and allowed traffic along the Wear without having to change trains.

The newest addition, currently under construction is that building to the south west, from Chester-le-Street, to Consett and serving all the smaller towns and villages along the way, with some calling for the future expansion from Consett back up to the MetroCentre - allowing the full integration of the Wearside and Airport Lines.

------------------

Notes: ups and downs here. The keen eyed will spot the lack of St James Park on the map; the route from By'er Grove terminates at Central Station - above ground, in the terminal bay platforms on the north side of the station as a cost cutting mechanism rather than more digging. On the up side, the network reaches north to Blyth and Ashington using what were freight rails, with freight trains allowed on the routes out of hours (ie. between 00:00-06:00, probably at a max of 20mph or something). Also reaches south to MetroCentre and Blaydon - even until the 1980s, BR services to the west towards Carlisle operated north of the Tyne and crossed and Blaydon using Scotswood Bridge. Here, Metro has grabbed the lines south of the Tyne to serve the MetroCentre, and BR has maintained the bridge. Also, BR has persisted in it's policy of segregation of light and heavy rail routes, so Metro uses it's own route to access Sunderland rather than sharing with BR - the sharing of routes was only approved after BR's privatisation and downfall. The use of the Leamside Line also brings the service to Washington, and points further south-west.

PS: the service level info is "up to", in the best of marketing collateral. Probably more like 8=6 and 4=3 outside of peak hours.

(*A) Clarity added, 01/Dec/2019, due to later events, and further refined (17/May/2020) to show the regional councils did not go ahead in 2004.

The easily identifiable Metro stations

In the early 1970s, the poor local transport system was identified as one of the main factors holding back the region's economy, and in 1971 a study was commissioned by the recently created Tyneside Passenger Transport Authority into how the transport system could be improved; this study recommended reviving the badly run down former Tyneside Electric network by converting it into an electrified rapid transit system, following the example of Manchester, and including a new underground section to better serve the busy central areas of Newcastle and Gateshead, as it was felt that the existing rail network didn't serve these areas adequately. These plans were approved by the Tyneside Metropolitan Railway Bill which was passed by Parliament in 1973. Around 70% of the funding for the scheme came from a central government grant, with the remainder coming from local sources which would benefit from the scheme.

British Rail also did much to help; the nationalised rail network at the time in the mid 1970s resembled a patient trying to limp his/her way to towards salvation. The East Coast Main Line north of Newcastle had repeatedly been slated for cutting, with ECML expresses terminated at Newcastle, and eliminating Anglo-Scottish services on the historic route. In the end, the route gained a last minute reprieve, although almost all feeder and local routes in the area north of the Tyne were to be eventually handed over to the locally operated network - although BR would retain freight privileges during out-of-hours. The first route, would follow the "Manchester Model" - a short cross-city tunnel connecting converted light rail routes on either side of the city, and would utilise the same general design and rolling stock as Manchester. Funding cuts, now notorious for hitting out-of-London projects, reared their heads at first during the planning when tunnels were further constricted to a diameter similar to London's deep tube lines, although still allowing joint procurement for stock with London.

Construction would start rapidly in 1974, with the new cross-Tyne bridge (later named the "Queen Elizabeth II Bridge" in common with many other bridges in the United Kingdom) quick to begin. Almost instantly, proposals surfaced for expanding the network which had to be tempered quickly by HM Treasury in order to prevent runaway funding. 5 years later, the only major extension was granted; a westfacing junction from Gateshead to the under construction MetroCentre and south side of the Tyne, with services extending to Blyth and Ashington. Funding cuts meant the second set of tunnels running on an east-west axis would be cancelled however, resulting the in the eastern access terminating directly at Central Station. The system opened in 1981, with a ceremony originally meant to include royals, but later downgraded to the Minister of Transport.

Early conceptual designs for the "Tyneside Metro"

By the 1990s, the original 4 coach rolling stock was proving difficult to maintain with the service falling in popularity due to drops in reliability. The units were similar to the evolution of earlier London Underground stock; it had single leaf doors, a similar orange interior and cab design. It also featured headlights that were positioned underneath the train body. However, unlike other tube stock, the the trains destined for the north-east proved to be unreliable, and further soured relations. Electrical generators for lighting the carriages failed often, as did the motors. Boarding of passengers was slow because of the single leaf doors. 2000 would see a reversal of fortunes, with a Government eager to play to it's strongholds outside of London; funding was eventually found for a new batch of trains, fully replacing the older units. Less trains would be needed than they were replacing, due to improved reliability, and capacity would be improved by the new trains stretching the full length of the 100m platforms, with articulated and walk-through coaches to make the best of the available space. The improvement in quality quickly showed as passengers numbers immediately begin to rise again; capacity is once again beginning to strain, particularly during the morning rush hour, whilst the routes were split out in to the "A-B-C" Lines, later retroactively better named using the same starting letters to bring some simplicity to navigating the network.

The revival in fortunes was further enhanced in 2004, when local Government re-organisation in England spurred the proposed reform of metropolitan county councils to form "Regional Councils" (with any overlapping counties retained for historical and ceremonial purposes only). This larger and reformed "upper level" of local government would receive further powers over local transportation, and the greater economies of scale was hoped to allow further expansions of the system. In the North-East, tensions and rivalry between Newcastle, Sunderland & Middlesbrough, or between Northumberland and County Durham made this difficult, and instead the Tyne & Wear transport authority received improved local transport powers, rather then the wide ranging prospects envisaged (*A). Extensions to the north and south, taking advantage of former freight-only branches which were being further downgraded (with freight operations retained at night when Metro operations ceased), with Sunderland and Washington joining the network. This also spurred the name change from "Tyneside Metro", to "North East Metro" - although still almost always just called [the] "Metro".

The last new lines, the Wearside and Peak Lines, were not really new "lines", in that they did not require any new physical tracks laid bar a new junction to allow operations from CLS Interchange towards Sunderland. New rolling stock came from refurbished London Underground stock, yet another cost-cutting measure, as London began to introduce a new batch of trains themselves. The Peak Line was introduced to bust congestion during the morning rush hour, along the northern shore of the Tyne, where further services could not formally be introduced to the entire Circle Line as the central core already operated at it's maximum of 24 trains per hour for the majority of the day. The new route, separated for simplicity on the map, allowed rush hour operations to help serve the stations, using the spare platforms already present at Tynemouth. The Wearside Line was also to alleviate congestion - although from the local roads, where congestion in to and out from Sunderland was rife, and allowed traffic along the Wear without having to change trains.

The newest addition, currently under construction is that building to the south west, from Chester-le-Street, to Consett and serving all the smaller towns and villages along the way, with some calling for the future expansion from Consett back up to the MetroCentre - allowing the full integration of the Wearside and Airport Lines.

------------------

Notes: ups and downs here. The keen eyed will spot the lack of St James Park on the map; the route from By'er Grove terminates at Central Station - above ground, in the terminal bay platforms on the north side of the station as a cost cutting mechanism rather than more digging. On the up side, the network reaches north to Blyth and Ashington using what were freight rails, with freight trains allowed on the routes out of hours (ie. between 00:00-06:00, probably at a max of 20mph or something). Also reaches south to MetroCentre and Blaydon - even until the 1980s, BR services to the west towards Carlisle operated north of the Tyne and crossed and Blaydon using Scotswood Bridge. Here, Metro has grabbed the lines south of the Tyne to serve the MetroCentre, and BR has maintained the bridge. Also, BR has persisted in it's policy of segregation of light and heavy rail routes, so Metro uses it's own route to access Sunderland rather than sharing with BR - the sharing of routes was only approved after BR's privatisation and downfall. The use of the Leamside Line also brings the service to Washington, and points further south-west.

PS: the service level info is "up to", in the best of marketing collateral. Probably more like 8=6 and 4=3 outside of peak hours.

(*A) Clarity added, 01/Dec/2019, due to later events, and further refined (17/May/2020) to show the regional councils did not go ahead in 2004.

Last edited:

An impact certainly, but what sort? The metro is going to run at a large loss, they always do, the question is will it generate enough benefits to make that cost worthwhile. Equally importantly will the local government be able to capture enough of that benefit in extra revenue to cover their costs? Given the way the UK tax system works, I suspect not. Which means something else is getting cut and council tax and local business rates are going up, not a great combination to spark any kind of revival.A decent rail system like this would make an impact on the revival of the NE during the 2000’s definatly.

Can I also state my amazement that those "Regional Council" reforms happened. The 2004 referendum was spectacularly defeated by a giant margin, so this new body is going to be massively unpopular and ripe for being shut down the moment there is a change in government. Which bodes ill for any transport network it is responsible for.

Devvy

Donor

A decent rail system like this would make an impact on the revival of the NE during the 2000’s definatly.

Are we seeing ‘joined up’ transport authorities in the Liverpool-Manchester-Leeds-Sheffield area too?

An impact certainly, but what sort? The metro is going to run at a large loss, they always do, the question is will it generate enough benefits to make that cost worthwhile. Equally importantly will the local government be able to capture enough of that benefit in extra revenue to cover their costs? Given the way the UK tax system works, I suspect not. Which means something else is getting cut and council tax and local business rates are going up, not a great combination to spark any kind of revival.

Can I also state my amazement that those "Regional Council" reforms happened. The 2004 referendum was spectacularly defeated by a giant margin, so this new body is going to be massively unpopular and ripe for being shut down the moment there is a change in government. Which bodes ill for any transport network it is responsible for.

The stuff about Middlesbrough was actually a mistake (now corrected - thank you!); I'm going to take that out as it was an earlier draft which clearly got mixed up in my Evernote for some reason, copy/paste failure! Think of the Regional Council as more like an enlarged Tyne and Wear County that then OTL North East Region (taking the urbanised areas of Northumberland and County Durham adjacent to T&W in to the Region, likely Blyth, Ashington, Cramlington & possibly Chester-le-Street). They are larger County Councils, renamed Regional Council and with extra powers (which as far as we are concerned with here are to do with having more interaction with BR then just funding new stations). There is scope for joint bodies between areas to cover further rail stuff, which is something I've pondered but not done anything about yet.

The larger Metro system has come through because of cuts saving a load of dosh from the east-west tunnel; but also good use of derelict/freight-only alignments and also delays compared to OTL to what we would call the Fleet or Jubilee Line. Manchester works are continuing, Merseyrail probably a toned down version of OTL, but I've not done much work on Merseyrail yet. Will the larger NE Metro have an impact. Probably. Will it cost more - yes, but ticket receipts will definitely be higher - a Metro connection to the MetroCentre will definitely encourage more people to take the Metro there. Likewise Washington residents can easily take the Metro to both Newcastle and Sunderland. The biggest group to lose out compared to OTL will be Sunderland FC fans...

Last edited:

The Metro going to the Metrocentre? Nah, it'll never catch on.Also reaches south to MetroCentre and Blaydon...

Interesting entry, Devvy. I was intrigued by the map and am amazed that something like that has not actually happened IOTL. The old Leamside Line goes right through Washington and also through Shiney Row, Fencehouses, Houghton le Spring, Leamside/West Rainton and passes right behind one of the Durham Park and Rides. It's only a short hop to Durham itself from there too. You have had it go towards Sunderland via Penshaw (Where an old track bed still exists)

I live just a couple of minutes' walk from the Leamside line and it's interesting to see that Network Rail haven't sold any of it off and the ballast and most of the infrastructure is still there and intact. I think it would be ideal to extend the Metro southwards towards Durham and connect it up with C-L-S and Sunderland via the Penshaw route you've already highlighted. While they're at it, they should also do the Consett Loop you mentioned, having the track from C-L-S going up there and then heading back down to Durham via Lanchester. No idea how much that would cost, but it would be brilliant for the North East!

Please keep these great updates coming!

I live just a couple of minutes' walk from the Leamside line and it's interesting to see that Network Rail haven't sold any of it off and the ballast and most of the infrastructure is still there and intact. I think it would be ideal to extend the Metro southwards towards Durham and connect it up with C-L-S and Sunderland via the Penshaw route you've already highlighted. While they're at it, they should also do the Consett Loop you mentioned, having the track from C-L-S going up there and then heading back down to Durham via Lanchester. No idea how much that would cost, but it would be brilliant for the North East!

Please keep these great updates coming!

1975-APT

Devvy

Donor

Advanced Passenger Train Development

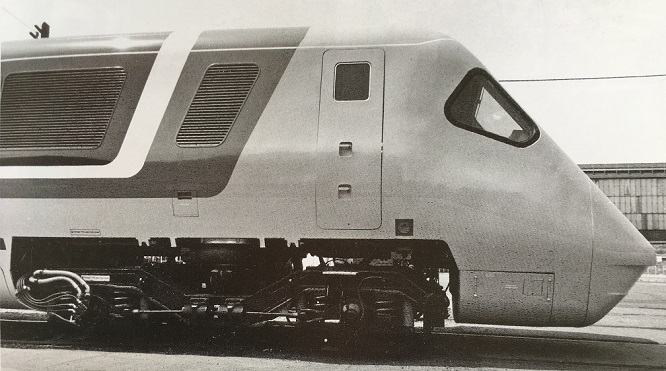

APT locomotive in side detail.

By 1972, the British Rail Board had approved further development with the Advanced Passenger Train, and with freight requirements rapidly falling off, the Great Central Main Line was surplus to requirements and likely to be at the very least mothballed. The requirements of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link would also play a part, with use of the APT for high speed London to Paris and Brussels services cropping up several times during discussions on the future train. The potential use of a dedicated train line for the APT offered up several advantages:

With funding agreed for the project development (1/2 from British Rail, and 1/2 from the Ministry of Transport), development continued - and the use of the GCML from Nottingham to Sheffield was authorised. The first act was "stringing up the wires", and installing electrification along the route. What should have been a fairly simple task, given the breadth of BR's national project for electrification, turned out to be 3 years of gruelling work, all to electrify 38 miles of double track - which should be directly usable if the project came to fruition. The non-standard nature of 25kV, caused several engineering concerns - electrical clearances for the high voltage lines had to theoretically be far larger (although later reduced after testing), new equipment was required for the transformers, and electrical interference from the alternating current all caused difficulties throughout the 3 years. The project improved when the experiences of SNCF, who had significantly more experience with 25kV then BR, was finally listened to, but it would still not be until 1975 when power was finally switched on for the route.

On the other hand, the significant time taken to electrify the route between Sheffield Victoria and Nottingham Victoria stations and prepare it for testing gave time for rolling stock construction - to have something to actually test with. BR requested the funding for 6 sets of trains, each of 2+6 formation (2 locomotives and 6 carriages). Despite the negativity from the Treasury over the request, who preferred only 2 sets given that this was designed for testing and development, an agreement for 3 sets was finally achieved, with some loan funding granted by the European Investment Bank. This was partly achieved by British Rail's agreement to allow private manufacturers to build the test trains, as part of Government initiatives to reflate the economy and private sector, however the wider industry demonstrated an acute lack of interest in the APT project on more than one occasion.

As design progressed, there were several key design principles which were kept in mind:

APT articulated coach

By 1973, critical design work was reaching completion, with the end configuration largely determined by the passenger business of British Rail rather than engineers. The dedicated nature of the route would allow the full length trains to be run; 14 carriages, resulting in a roughly 300 metre long train. 2 power cars would provide significant propulsion, 4 first class carriages, 7 first class carriages, and a catering car would provide the formation.

The main sticking point was discussions with HM Railway Inspectorate over the power provisions. The use of 2 pantographs (one for each locomotive) was unsuitable - research had already shown that the first would cause ripples in the cable which would severely undermine power collection from the second pantograph. Having a locomotive at either end was preferable, but the provision of a high tension power cable along the length of the train to connect the locomotives bothered HMRI on safety reasons - something which did not seem to matter abroad.

The removal of the ability to tilt due to the use of the better engineered Great Central Route seemed to placate the HMRI and a compromise was reached, allowing the creation of a 12 coach train, flanked by a locomotive at either end, rather than the alternative of two "half-trains". Weight concerns did however force the addition of an extra bogie on the locomotive, removing it from the train articulation, although the 4 sets of axles, along with the 2 axles on the closest bogie of the adjacent passenger carriage would now be powered, improving traction - a move which almost copied verbatim the designs of SNCF for their TGV development. Although the carriages were shorter than originally conceived (at 21 metres), the use of articulation allowed the same spaces, and same amount of seating inside as earlier. In a quiet, but now seemingly strange move, the use of tapering walls was retained - now thought to be insurance against accusations of "wasted development", and allow BR to retrofit tilting to the trains later if required. This was never taken up, and although the above seat storage area is smaller, careful design of the interior would avoid a cramped look.

---------------------------------

Notes: A big thank you specifically here to a certain "David Clough" whose book on the APT continues to be invaluable for research on the topic.

APT research and development continues, now between Nottingham Vic and Sheffield Vic stations. Nods to El Pip in the electrification problems....

APT locomotive in side detail.

By 1972, the British Rail Board had approved further development with the Advanced Passenger Train, and with freight requirements rapidly falling off, the Great Central Main Line was surplus to requirements and likely to be at the very least mothballed. The requirements of the Channel Tunnel Rail Link would also play a part, with use of the APT for high speed London to Paris and Brussels services cropping up several times during discussions on the future train. The potential use of a dedicated train line for the APT offered up several advantages:

- The train could be thoroughly tested, developed and refined without any effect on existing services.

- The GCML route was built to reasonably high standards, and would allow faster operations potentially without tilting, thereby removing significant technical complexity from the train design.

- The route could be separated from the main BR network, and could therefore act as a testbed for the required 25kV AC electrification.

- The presence of only one level crossing (near Sheffield), which could be rebuilt as a bridge.

- New signalling standards could be tested, without impact on other trains.

With funding agreed for the project development (1/2 from British Rail, and 1/2 from the Ministry of Transport), development continued - and the use of the GCML from Nottingham to Sheffield was authorised. The first act was "stringing up the wires", and installing electrification along the route. What should have been a fairly simple task, given the breadth of BR's national project for electrification, turned out to be 3 years of gruelling work, all to electrify 38 miles of double track - which should be directly usable if the project came to fruition. The non-standard nature of 25kV, caused several engineering concerns - electrical clearances for the high voltage lines had to theoretically be far larger (although later reduced after testing), new equipment was required for the transformers, and electrical interference from the alternating current all caused difficulties throughout the 3 years. The project improved when the experiences of SNCF, who had significantly more experience with 25kV then BR, was finally listened to, but it would still not be until 1975 when power was finally switched on for the route.

On the other hand, the significant time taken to electrify the route between Sheffield Victoria and Nottingham Victoria stations and prepare it for testing gave time for rolling stock construction - to have something to actually test with. BR requested the funding for 6 sets of trains, each of 2+6 formation (2 locomotives and 6 carriages). Despite the negativity from the Treasury over the request, who preferred only 2 sets given that this was designed for testing and development, an agreement for 3 sets was finally achieved, with some loan funding granted by the European Investment Bank. This was partly achieved by British Rail's agreement to allow private manufacturers to build the test trains, as part of Government initiatives to reflate the economy and private sector, however the wider industry demonstrated an acute lack of interest in the APT project on more than one occasion.

As design progressed, there were several key design principles which were kept in mind:

- The need to keep the train lightweight and streamlined to reduce energy requirements and allow higher speeds.

- Train articulation to further reduce weight and maintenance requirements on both track and train.

- A high level of passenger comfort inside with excellent suspension.

- Regenerative braking to allow efficient braking performance at high speeds without brake wear.

APT articulated coach

By 1973, critical design work was reaching completion, with the end configuration largely determined by the passenger business of British Rail rather than engineers. The dedicated nature of the route would allow the full length trains to be run; 14 carriages, resulting in a roughly 300 metre long train. 2 power cars would provide significant propulsion, 4 first class carriages, 7 first class carriages, and a catering car would provide the formation.

The main sticking point was discussions with HM Railway Inspectorate over the power provisions. The use of 2 pantographs (one for each locomotive) was unsuitable - research had already shown that the first would cause ripples in the cable which would severely undermine power collection from the second pantograph. Having a locomotive at either end was preferable, but the provision of a high tension power cable along the length of the train to connect the locomotives bothered HMRI on safety reasons - something which did not seem to matter abroad.

The removal of the ability to tilt due to the use of the better engineered Great Central Route seemed to placate the HMRI and a compromise was reached, allowing the creation of a 12 coach train, flanked by a locomotive at either end, rather than the alternative of two "half-trains". Weight concerns did however force the addition of an extra bogie on the locomotive, removing it from the train articulation, although the 4 sets of axles, along with the 2 axles on the closest bogie of the adjacent passenger carriage would now be powered, improving traction - a move which almost copied verbatim the designs of SNCF for their TGV development. Although the carriages were shorter than originally conceived (at 21 metres), the use of articulation allowed the same spaces, and same amount of seating inside as earlier. In a quiet, but now seemingly strange move, the use of tapering walls was retained - now thought to be insurance against accusations of "wasted development", and allow BR to retrofit tilting to the trains later if required. This was never taken up, and although the above seat storage area is smaller, careful design of the interior would avoid a cramped look.

---------------------------------

Notes: A big thank you specifically here to a certain "David Clough" whose book on the APT continues to be invaluable for research on the topic.

APT research and development continues, now between Nottingham Vic and Sheffield Vic stations. Nods to El Pip in the electrification problems....

1975-Railfreight

Devvy

Donor

Excerpts from "A History of British Rail's Railfreight"

Freightliner was created in the 1960s

Introduction

Railfreight in Great Britain owes, in a reverse of the passenger sector, a lot to the Beeching Reforms of the 1960s. The old style "any freight, to any where" method of rail freight, with hundreds of stations each with their own freight yard, was doomed - it was an incredibly inefficient method of operation, with huge expenses and fixed costs regardless of the actual volume of freight. The "Freightliner" concept was spearheaded by Beeching himself, foreseeing a network of "liner trains" rushing intermodal containers across the country, allowing full interoperability with the large container ships then coming in to fashion. Whilst teething problems were found - mostly with rail unions and formation inflexibility, the services proved popular and efficient, especially on the longer distance services such as London to Glasgow.

Under the 1968 Act, Freightliner was to be an arm's length company from British Rail - technically part of the National Freight Corporation, but obviously operating on British Rail tracks, for which it would lease access rights, rolling stock and depots. This was British Rail's first experience of what was tacitly a privatisation move - a move which would herald positives and negatives in future years. Early wins included operations for vehicle companies includes Ford and Rootes, and regional terminals began to open at Nottingham, Swansea, Manchester Trafford Park, Birmingham Landor Street, the latter two complementing the existing terminals at Longsight and Dudley respectively. By the 1970s, the sea ports were becoming rail connected; Southampton, Tilbury and Felixstowe all had connections by 1974, and traffic quickly rose on conveying containers from the sea terminals to inland terminals - a move unforeseen in the 1960s, but now widely recognised as an almost inevitable consequence of the switch to intermodal containers. However, by the late 1970s, there was a glut of depots, and some closures were looking to be likely - Newcastle, Hull, Longsight, Nottingham, Swansea, Aberdeen, Dundee and Edinburgh all were under-utilised. The promise of the soon to open Channel Tunnel was all that kept them going in the short term.

The other activity in the 1970s was the introduction of the "Speedlink" service. This was a reworking of the classic wagonload freight concept; private companies loading a wagon with their wares, and having it conveyed to another point on the network for unloading. The smaller wagons meant greater speeds were possible, and the initial Bristol-Glasgow service in 1973 conveyed a wide array of goods; tobacco, chocolate, clay, soap powder, newsprint, drinks, motor parts and aluminium. The wagons were air-braked and mostly owned by British Rail, offering great flexibility for customers, and they were capable of 75mph. However, the initial successes of Speedlink caused the thing which Speedlink was trying to avoid; the convoluted network of services of the previous wagonload services. For Speedlink, the wider SNCF wagonload services offered an ideal partner for a wider network, and the Channel Tunnel future looked promising.

----------------------------------

Excerpt from Briefipedia

French Time at Gare du Lyon

Introduction

The Western Europe Working Group (commonly referred to in English as "the Wegger Group ") is a intergovernmental working group, composed predominately of the United Kingdom (*1), Republic of Ireland, French Republic, Kingdom of the Netherlands and Kingdom of Belgium. Associate members also form part of the group, usually adopting the same standards, with consist of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Principality of Monaco. It is one of the six regional associations within the European Union (along with Iberia, the Nordics, the DACH region, the Baltics, and Visegrad Group), which provide an enhanced level of co-operation between EU member states in various regions, which being smaller in membership, is easier to achieve agreement for contentious topics.

History

The WEWG was an evolution from an earlier rail treaty between the United Kingdom, France, Netherlands and Belgium, in order to co-operate in the construction of not only the Channel Tunnel, but also the supporting infrastructure on both sides. Come the 1970s, the planned "BLAP Network", consisting of an international train service between Brussels, London, Amsterdam and Paris was continuing to evolve and move towards construction and fruition. The French were working on two new high speed rail links, between Paris and Calais/Lille, and Paris to Lyons. Belgium was working on Lille-Brussels-Antwerp, and the Dutch from Antwerp/Belgian border to Rotterdam and Amsterdam. The British however, as usual, almost managed to torpedo the group, by initially concentrating on a high speed line from London to the north of England, before later expanding the scope to cover the route from London to the Channel Tunnel.

The WEWG would score an early win in 1976 with the French adoption of daylight savings time (due to the 1973 Oil Crisis), moving one hour backwards in winter, thereby adopting the same time zone and Britain & Ireland for the purposes of timetable simplification in preparation for the Channel Tunnel. This also aligned France with their natural time zone, making morning more light. The domino effect was immediate; Belgium quickly followed, as did the Netherlands, leaving the Rhine as the natural time boundary between France and Germany - who had not participated in the original Rail Treaty anyhow. This was later followed in 1977 by the creation of the WEWG Rail License, mandatory for any train driver working cross-border, initially targeted at the international high speed trains.

Later acts would see further harmonisation; vehicle registration plates (driving licenses harmonised at the European level), common standards on ID/Passport Cards, road tolling mechanisms, a unified postal code system and a unified telephone network.

(*1) the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland, and also including the Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey and Gibraltar (Gibraltar despite protests by Spain over the Gibraltar status dispute).

----------------------------------

Notes:

Firstly Railfreight. It's all roughly OTL; railfreight was one thing reformed well in the 1960s and 1970s bar lack of funds. The earlier Channel Tunnel has an opportunity to change these sectors for the better though.

Second, the "WEWG". I'll freely admit to French politics of the 1970s not being a strong point of mine. However, they adopted daylight savings time in 1976, in response to the oil crisis. The fact the Channel Tunnel is under construction here, as are high speed links between the BLAP cities, means there is more of an incentive to move back an hour in winter (instead of forward an hour in summer), aligning France with "natural time", and synchronising with the UK making timetabling easier. France then dominos Belgium and the Netherlands. Spain would likely follow at some point regardless as now both Portugal on one side and France on the other are on GMT. Germany I have no idea about....but here the EU still exists, and does it's "good work" as usual. However, there are several regional groups who carry out their own integration/harmonisation projects - nothing supranational, just harmonisation. Having a harmonised post code doesn't impinge on anyone's sovereignty if it's properly organised, and the US/Canada et al all manage to share a telephone numbering schema without issue (a pan European telephone scheme was floated in the 90s it seems, but the Herculean effort required killed it off. Having smaller groups of countries doing it seems more manageable). Also European Rail Licenses for cross-border operations.

Freightliner was created in the 1960s

Introduction

Railfreight in Great Britain owes, in a reverse of the passenger sector, a lot to the Beeching Reforms of the 1960s. The old style "any freight, to any where" method of rail freight, with hundreds of stations each with their own freight yard, was doomed - it was an incredibly inefficient method of operation, with huge expenses and fixed costs regardless of the actual volume of freight. The "Freightliner" concept was spearheaded by Beeching himself, foreseeing a network of "liner trains" rushing intermodal containers across the country, allowing full interoperability with the large container ships then coming in to fashion. Whilst teething problems were found - mostly with rail unions and formation inflexibility, the services proved popular and efficient, especially on the longer distance services such as London to Glasgow.

Under the 1968 Act, Freightliner was to be an arm's length company from British Rail - technically part of the National Freight Corporation, but obviously operating on British Rail tracks, for which it would lease access rights, rolling stock and depots. This was British Rail's first experience of what was tacitly a privatisation move - a move which would herald positives and negatives in future years. Early wins included operations for vehicle companies includes Ford and Rootes, and regional terminals began to open at Nottingham, Swansea, Manchester Trafford Park, Birmingham Landor Street, the latter two complementing the existing terminals at Longsight and Dudley respectively. By the 1970s, the sea ports were becoming rail connected; Southampton, Tilbury and Felixstowe all had connections by 1974, and traffic quickly rose on conveying containers from the sea terminals to inland terminals - a move unforeseen in the 1960s, but now widely recognised as an almost inevitable consequence of the switch to intermodal containers. However, by the late 1970s, there was a glut of depots, and some closures were looking to be likely - Newcastle, Hull, Longsight, Nottingham, Swansea, Aberdeen, Dundee and Edinburgh all were under-utilised. The promise of the soon to open Channel Tunnel was all that kept them going in the short term.

The other activity in the 1970s was the introduction of the "Speedlink" service. This was a reworking of the classic wagonload freight concept; private companies loading a wagon with their wares, and having it conveyed to another point on the network for unloading. The smaller wagons meant greater speeds were possible, and the initial Bristol-Glasgow service in 1973 conveyed a wide array of goods; tobacco, chocolate, clay, soap powder, newsprint, drinks, motor parts and aluminium. The wagons were air-braked and mostly owned by British Rail, offering great flexibility for customers, and they were capable of 75mph. However, the initial successes of Speedlink caused the thing which Speedlink was trying to avoid; the convoluted network of services of the previous wagonload services. For Speedlink, the wider SNCF wagonload services offered an ideal partner for a wider network, and the Channel Tunnel future looked promising.

----------------------------------

Excerpt from Briefipedia

French Time at Gare du Lyon

Introduction

The Western Europe Working Group (commonly referred to in English as "the Wegger Group ") is a intergovernmental working group, composed predominately of the United Kingdom (*1), Republic of Ireland, French Republic, Kingdom of the Netherlands and Kingdom of Belgium. Associate members also form part of the group, usually adopting the same standards, with consist of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg and Principality of Monaco. It is one of the six regional associations within the European Union (along with Iberia, the Nordics, the DACH region, the Baltics, and Visegrad Group), which provide an enhanced level of co-operation between EU member states in various regions, which being smaller in membership, is easier to achieve agreement for contentious topics.

History

The WEWG was an evolution from an earlier rail treaty between the United Kingdom, France, Netherlands and Belgium, in order to co-operate in the construction of not only the Channel Tunnel, but also the supporting infrastructure on both sides. Come the 1970s, the planned "BLAP Network", consisting of an international train service between Brussels, London, Amsterdam and Paris was continuing to evolve and move towards construction and fruition. The French were working on two new high speed rail links, between Paris and Calais/Lille, and Paris to Lyons. Belgium was working on Lille-Brussels-Antwerp, and the Dutch from Antwerp/Belgian border to Rotterdam and Amsterdam. The British however, as usual, almost managed to torpedo the group, by initially concentrating on a high speed line from London to the north of England, before later expanding the scope to cover the route from London to the Channel Tunnel.

The WEWG would score an early win in 1976 with the French adoption of daylight savings time (due to the 1973 Oil Crisis), moving one hour backwards in winter, thereby adopting the same time zone and Britain & Ireland for the purposes of timetable simplification in preparation for the Channel Tunnel. This also aligned France with their natural time zone, making morning more light. The domino effect was immediate; Belgium quickly followed, as did the Netherlands, leaving the Rhine as the natural time boundary between France and Germany - who had not participated in the original Rail Treaty anyhow. This was later followed in 1977 by the creation of the WEWG Rail License, mandatory for any train driver working cross-border, initially targeted at the international high speed trains.

Later acts would see further harmonisation; vehicle registration plates (driving licenses harmonised at the European level), common standards on ID/Passport Cards, road tolling mechanisms, a unified postal code system and a unified telephone network.

(*1) the United Kingdom of Great Britain & Northern Ireland, and also including the Isle of Man, Jersey, Guernsey and Gibraltar (Gibraltar despite protests by Spain over the Gibraltar status dispute).

----------------------------------

Notes:

Firstly Railfreight. It's all roughly OTL; railfreight was one thing reformed well in the 1960s and 1970s bar lack of funds. The earlier Channel Tunnel has an opportunity to change these sectors for the better though.

Second, the "WEWG". I'll freely admit to French politics of the 1970s not being a strong point of mine. However, they adopted daylight savings time in 1976, in response to the oil crisis. The fact the Channel Tunnel is under construction here, as are high speed links between the BLAP cities, means there is more of an incentive to move back an hour in winter (instead of forward an hour in summer), aligning France with "natural time", and synchronising with the UK making timetabling easier. France then dominos Belgium and the Netherlands. Spain would likely follow at some point regardless as now both Portugal on one side and France on the other are on GMT. Germany I have no idea about....but here the EU still exists, and does it's "good work" as usual. However, there are several regional groups who carry out their own integration/harmonisation projects - nothing supranational, just harmonisation. Having a harmonised post code doesn't impinge on anyone's sovereignty if it's properly organised, and the US/Canada et al all manage to share a telephone numbering schema without issue (a pan European telephone scheme was floated in the 90s it seems, but the Herculean effort required killed it off. Having smaller groups of countries doing it seems more manageable). Also European Rail Licenses for cross-border operations.

That time zone change is epic yet subtle. Time zones changed to better match the longitude countries are in is awesome to the max.

Having EU subregions go for deeper partnerships instead of trying to wrangle the whole area to a better Union? Realistic (The African Union is explicitly doing this right now OTL). Saddens me a bit for being very pro-EU, but if it works it works. Having a more integrated rail system per region would be great. The part were Belgium switches to the same electricity for trains: another great part. I can see this deeper cooperation resulting in signalling systems being aligned far earlier than ERTMS if done per grouping.

So, how better off than OTL is the UK railfreight? Noticeably, Marginally or just better set up to handle future market changes?

Having EU subregions go for deeper partnerships instead of trying to wrangle the whole area to a better Union? Realistic (The African Union is explicitly doing this right now OTL). Saddens me a bit for being very pro-EU, but if it works it works. Having a more integrated rail system per region would be great. The part were Belgium switches to the same electricity for trains: another great part. I can see this deeper cooperation resulting in signalling systems being aligned far earlier than ERTMS if done per grouping.

So, how better off than OTL is the UK railfreight? Noticeably, Marginally or just better set up to handle future market changes?

Last edited:

Devvy

Donor

Now that's a nice Alt APT/125 AU.

Also nice that the Great Central Main Line survives to be used as HS1!

The GCML won't be as fast as HS1; it's definitely more bendy which will keep speeds down on a non-tilting train. However, having only fast trains on it reduces the bad effects of differential speeds mixing. I've done calculations on journey times (a massive spreadsheet full of formulas!), but you'll have to wait a few chapters for that

First they came for their timezone and I did nothing

Haha

Very nice update!

I like how freight is going here.

I take it sleepers and such are still going.

Did you say the 'carferry' concept was dead?

Freight is roughly the same as OTL; the only prime difference will be in the future given the Channel Tunnel will arrive 10-15 years earlier.

Some sleepers are still going; the prime candidates are obviously London to Central Belt Scotland and beyond, London to West Wales, London to Cornwall. Bristol to Scotland might still be around.

Motorail still lingers too (we are only in the 1970s currently!); there's obviously scope for cross-Channel operations here in future.

That time zone change is epic yet subtle. Time zones changed to better match the longitude countries are in is awesome to the max.

Having EU subregions go for deeper partnerships instead of trying to wrangle the whole area to a better Union? Realistic (The African Union is explicitly doing this right now OTL). Saddens me a bit for being very pro-EU, but if it works it works. Having a more integrated rail system per region would be great. The part were Belgium switches to the same electricity for trains: another great part. I can see this deeper cooperation resulting in signalling systems being aligned far earlier than ERTMS if done per grouping.

So, how better off than OTL is the UK railfreight? Noticeably, Marginally or just better set up to handle future market changes?

As above, but the railfreight is roughly the same as per OTL, but it's just going to get a hit of cross-Channel freight earlier than OTL, and some other tweaks as well. OTL, Speedlink (wagonload services) were killed off in the early 1990s only a couple of years before the Channel Tunnel opened, and SNCF even today in OTL retains a significant wagonload business (whether profitable or not). There's definitely scope there for growth. (Speedlink closed as it was a financial loss OTL, and there's no scope for privatising a loss making entity, so it was closed).

Timezone wise; I can understand OTL France's move; at the time in 1976 there was little scope of a Channel Tunnel in the foreseeable future, so why not stick on the same time zone as Germany on it's border (and Spain to a lesser degree). Here, with the Channel Tunnel well underway, plenty of scope for cross-border services, and the Germans staying out of the original rail treaty, there's more interest in aligning with Britain from the outset.

PS: as a small sidenote, the UK de facto adopted CET between 1968-1971 by staying on BST all year round, which synchronised with France. So here, the UK reverted to Winter/UTC, Summer/UTC+1 in 1971; France followed suit in 1976 along with Benelux later in 1976, and Spain probably copying in 1980 (which would have a massive impact there considering how askew Spanish time is to natural time in OTL, and would align Spain in to one time zone as well, with the Canary Islands being an hour behind OTL.

As you say, I think regionalised partnerships might be more successful, especially if such harmonisation is done by intergovernmental agreement rather than top-down supranational laws. Keeps the UK and others happy on retaining "sovereignty" over it's laws, but also allows easier agreement with less parties to agree to something. The DACH region already predominately use 15kV AC rail power by this point in OTL, so that kind of thing is easy to harmonise in DACH. Likewise Iberia have their own track gauge, etc etc, the list goes on. There's still the EEC/EU underneath though, guaranteeing the Single Market, the Euro in future and a raft of other things.

1976-Beck-Line

Devvy

Donor

1975 - Beck Line

Beck Line trains in later years; note the similarity to Circle Line trains.

The 1943 County of London plan contained several new ideas and plans for the post-war era, but it was weak on the subject of transport requirements for the future of London. Concepts such as a linking the stations together were abandoned as expensive and impractical, however the idea of linking the ex-Southern Railway termini together with a quicker direct tube was not immediately lost until later years. Some of these concepts slowly meshed with immediate pressing issues now affecting operations in the 1960s. The Bakerloo Line junction at Baker Street still caused congestion issues between Baker Street and Oxford Circus. Desires to better serve South London by politicians factored in, as was a desire by the same group to stimulate regeneration in the depressed areas of the Docklands. However, the requirements of British Rail in modernisation and regeneration, as well as the lengthy construction schedule of the Viking Line by London Transport pushed thoughts for a second post-war cross-London link back.

A joint working party by London Transport and British Rail in 1970 finally began detailed investigative work in to the potential for a new link. By now the Viking Line had been open for 3 years, and the substantial rise in usage due to the faster links it provided between essential BR stations, as well as commuter services from more outlying areas could be well seen. Plans evolved from a small tube line to a larger loading gauge allowing larger trains to operate. A desire to reorganise transport in north-west London along the Metropolitan axis and finally solve the rampant congestion issues was sought, and BR could see the potential in offering some easily separated suburban routes which would potentially allow them to close Marylebone station (*1) and save a not insignificant amount of cash - essential to any nationalised industry in the 1970s. At the same time, the incoming new boss of British Railways, Richard Marsh declared his intentions to "...run British Rail as a business".

Part of this meant further "localisation" tactics, with Marsh commenting "I see no reason why the nation should pay for trains to be used for 4 hours a day for one city and remain dormant the rest of the time." Marsh would see several easily separated routes in several cities handed over to the local authorities during his time in office during the 1970s. In any case, the lines were often run down, dirty and poorly maintained by the 1970s, with British Rail lacking the funds required for any serious effort at modernisation and the provision of an attractive and marketable service.

It would not be until 1976 that Parliament duly authorised construction of the new link, with significant Parliamentary time lost in the 1970s due to the Cublington Airport project amid repeated appeals by local residents. With a tunnel of almost 5m diameter, trains similar to the sub-surface line stock could be handled (and slightly larger specialised stock potentially subject to conditions in the suburban stations), providing a significant capacity lift over that which was now becoming a millstone around the neck of the Viking Line. Taking over several branches to the north-west such as Aylesbury, Watford and Uxbridge, and leaving the (simplified) Metropolitan Line to share the northern side of the Circle Line. To the south and east, using the former docks as sites for stations was an easy cost saving measure, and using former railways alignments in East London would likewise reduce costs. Lastly, the Mid-Kent Line in South London could be easily separated from the main BR network, allowing access to population deep within the southern reaches of London. The line's route, along the Strand and Fleet Street was shifted north slightly to serve the British Rail station at Holborn Viaduct, which London Transport and British Rail had compromised on, proposing to use it a terminus for the Channel Tunnel rail link if suitable Underground connections were made.

The "gold-plated" tube line was not lost on those from outside of the capital; although London was suffering from chronic road congestion, resulting in a political and social effort for better public transport, and would link together heavy rail routes on either end (thus making a more heavy rail solution through the capital a better proposition), it came on the back of stringent cuts and cost cutting to projects in the north of England and Scotland. The backing for a new airport serving London in Cublington, just past the end of one of the route termini in Aylesbury was an added boon for the new line with an easy extension possible, further enhancing it's investment credentials. Contracts promising funding by Olympia & York, who in return were renovating the dilapidated Canary Wharf area in to a new business district also provided a welcome extra layer of funding.

Marylebone Station in previous years; it's now a well used exhibition hall for trade shows

These parts of cost-saving proved essential in providing the business case to central Government, although were far from without debate. British Rail wanted to effectively hand over service responsibility to London Transport to re-engineer and then sell the land to provide needed income. London Transport wanted to take over the route and services together, and re-engineer as necessary. Plans were then further complicated by another area of British Rail wanting to use the Great Central Main Line for high speed operations, which potentially placed the terminus at Marylebone - an idea which was later discarded due to lack of Underground connections for dispersing passengers. An agreement was finally reached with a revenue sharing deal for any land sale related to the project, with the lions share going to the new line's construction and a smaller proportion to British Rail to fund further modernisation of Chiltern Route in to Paddington station in lieu of Marylebone. Construction would finally begin in 1980, on what would later be known as the "Beck Line", after the designer of the now legendary "Tube Map", but also in the absence of any other name which was suitably short and catchy. In later years, London Transport authorities would make substantial revenues from a sponsorship deal in association with the German beer "Beck's".

---------------------

(*1) As was suggested several times during OTL 1980s, but never managed to stick.

The rebranded Fleet/Jubilee Line is here, named for Harry Beck in this ATL who came up with the Tube Map we all love. It's begun construction after 1977 (the Queen's Silver Jubilee), so has missed out on the opportunity to name it the Jubilee Line. Extensive congestion in London, cost cutting for BR, regeneration for the Docklands, and contributions by developers have helped this get over the line, in what is half way between Crossrail suggested at the time, and the OTL Fleet/Jubilee Line. Although "gold-plated" from the perspective of the North, platforms would only be approx 130 metres long, fitting in a 7 coach D stock train (DM-T-DM-T-DM-T-DM) - not exactly massively longer than Manchester at 100 metres. However, the central tunnel section is obviously much, much longer.

The larger loading gauge allows larger trains to operate however, although still on a segregated London Transport route. The fact that this ATL-Jubilee Line is beginning construction almost 10 years later then OTL, and the corresponding extra congestion on both the London roads and the London Underground network has also helped push this through; there was a clear social, business, congestion, regenerative requirement for it.

Note the suggestion of Holborn Viaduct as a terminus for the Channel Tunnel Rail link. Business-wise, the terminus needs to be central London, and the rail standards for high speed suggest a separate route if possible (as well as general congestion on other routes). Tunnels to Kings Cross were OTL (and here in ATL) British Rail's first choice, but that's financially unacceptable for an unproven business case for the link. This is something we'll cover later!

Beck Line trains in later years; note the similarity to Circle Line trains.

The 1943 County of London plan contained several new ideas and plans for the post-war era, but it was weak on the subject of transport requirements for the future of London. Concepts such as a linking the stations together were abandoned as expensive and impractical, however the idea of linking the ex-Southern Railway termini together with a quicker direct tube was not immediately lost until later years. Some of these concepts slowly meshed with immediate pressing issues now affecting operations in the 1960s. The Bakerloo Line junction at Baker Street still caused congestion issues between Baker Street and Oxford Circus. Desires to better serve South London by politicians factored in, as was a desire by the same group to stimulate regeneration in the depressed areas of the Docklands. However, the requirements of British Rail in modernisation and regeneration, as well as the lengthy construction schedule of the Viking Line by London Transport pushed thoughts for a second post-war cross-London link back.

A joint working party by London Transport and British Rail in 1970 finally began detailed investigative work in to the potential for a new link. By now the Viking Line had been open for 3 years, and the substantial rise in usage due to the faster links it provided between essential BR stations, as well as commuter services from more outlying areas could be well seen. Plans evolved from a small tube line to a larger loading gauge allowing larger trains to operate. A desire to reorganise transport in north-west London along the Metropolitan axis and finally solve the rampant congestion issues was sought, and BR could see the potential in offering some easily separated suburban routes which would potentially allow them to close Marylebone station (*1) and save a not insignificant amount of cash - essential to any nationalised industry in the 1970s. At the same time, the incoming new boss of British Railways, Richard Marsh declared his intentions to "...run British Rail as a business".

Part of this meant further "localisation" tactics, with Marsh commenting "I see no reason why the nation should pay for trains to be used for 4 hours a day for one city and remain dormant the rest of the time." Marsh would see several easily separated routes in several cities handed over to the local authorities during his time in office during the 1970s. In any case, the lines were often run down, dirty and poorly maintained by the 1970s, with British Rail lacking the funds required for any serious effort at modernisation and the provision of an attractive and marketable service.

It would not be until 1976 that Parliament duly authorised construction of the new link, with significant Parliamentary time lost in the 1970s due to the Cublington Airport project amid repeated appeals by local residents. With a tunnel of almost 5m diameter, trains similar to the sub-surface line stock could be handled (and slightly larger specialised stock potentially subject to conditions in the suburban stations), providing a significant capacity lift over that which was now becoming a millstone around the neck of the Viking Line. Taking over several branches to the north-west such as Aylesbury, Watford and Uxbridge, and leaving the (simplified) Metropolitan Line to share the northern side of the Circle Line. To the south and east, using the former docks as sites for stations was an easy cost saving measure, and using former railways alignments in East London would likewise reduce costs. Lastly, the Mid-Kent Line in South London could be easily separated from the main BR network, allowing access to population deep within the southern reaches of London. The line's route, along the Strand and Fleet Street was shifted north slightly to serve the British Rail station at Holborn Viaduct, which London Transport and British Rail had compromised on, proposing to use it a terminus for the Channel Tunnel rail link if suitable Underground connections were made.

The "gold-plated" tube line was not lost on those from outside of the capital; although London was suffering from chronic road congestion, resulting in a political and social effort for better public transport, and would link together heavy rail routes on either end (thus making a more heavy rail solution through the capital a better proposition), it came on the back of stringent cuts and cost cutting to projects in the north of England and Scotland. The backing for a new airport serving London in Cublington, just past the end of one of the route termini in Aylesbury was an added boon for the new line with an easy extension possible, further enhancing it's investment credentials. Contracts promising funding by Olympia & York, who in return were renovating the dilapidated Canary Wharf area in to a new business district also provided a welcome extra layer of funding.

Marylebone Station in previous years; it's now a well used exhibition hall for trade shows

These parts of cost-saving proved essential in providing the business case to central Government, although were far from without debate. British Rail wanted to effectively hand over service responsibility to London Transport to re-engineer and then sell the land to provide needed income. London Transport wanted to take over the route and services together, and re-engineer as necessary. Plans were then further complicated by another area of British Rail wanting to use the Great Central Main Line for high speed operations, which potentially placed the terminus at Marylebone - an idea which was later discarded due to lack of Underground connections for dispersing passengers. An agreement was finally reached with a revenue sharing deal for any land sale related to the project, with the lions share going to the new line's construction and a smaller proportion to British Rail to fund further modernisation of Chiltern Route in to Paddington station in lieu of Marylebone. Construction would finally begin in 1980, on what would later be known as the "Beck Line", after the designer of the now legendary "Tube Map", but also in the absence of any other name which was suitably short and catchy. In later years, London Transport authorities would make substantial revenues from a sponsorship deal in association with the German beer "Beck's".

---------------------

(*1) As was suggested several times during OTL 1980s, but never managed to stick.

The rebranded Fleet/Jubilee Line is here, named for Harry Beck in this ATL who came up with the Tube Map we all love. It's begun construction after 1977 (the Queen's Silver Jubilee), so has missed out on the opportunity to name it the Jubilee Line. Extensive congestion in London, cost cutting for BR, regeneration for the Docklands, and contributions by developers have helped this get over the line, in what is half way between Crossrail suggested at the time, and the OTL Fleet/Jubilee Line. Although "gold-plated" from the perspective of the North, platforms would only be approx 130 metres long, fitting in a 7 coach D stock train (DM-T-DM-T-DM-T-DM) - not exactly massively longer than Manchester at 100 metres. However, the central tunnel section is obviously much, much longer.

The larger loading gauge allows larger trains to operate however, although still on a segregated London Transport route. The fact that this ATL-Jubilee Line is beginning construction almost 10 years later then OTL, and the corresponding extra congestion on both the London roads and the London Underground network has also helped push this through; there was a clear social, business, congestion, regenerative requirement for it.

Note the suggestion of Holborn Viaduct as a terminus for the Channel Tunnel Rail link. Business-wise, the terminus needs to be central London, and the rail standards for high speed suggest a separate route if possible (as well as general congestion on other routes). Tunnels to Kings Cross were OTL (and here in ATL) British Rail's first choice, but that's financially unacceptable for an unproven business case for the link. This is something we'll cover later!

1978-WCML

Devvy

Donor

The West Coast Roundup

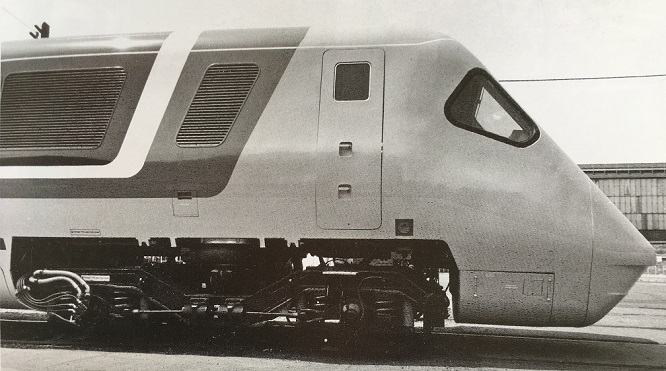

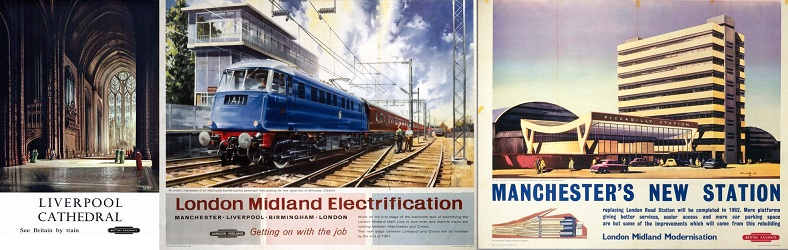

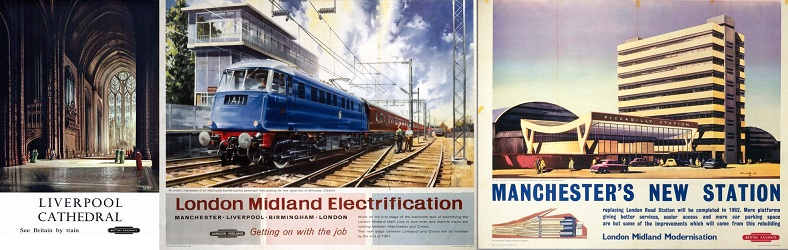

A selection of marketing material at the time.

The West Coast Route is the prime asset in the portfolio of British Rail. It connects most of the major British cities - London to: Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh, and several secondary cities, and is almost fully electrified from end to end.

London Euston is the southern terminus of the route. It has been completely rebuild since nationalisation, and now forms a sleek and modern railway station, fit for business for the modern passenger. The old remnants and complicated building have been swept away in favour of open spaces, restaurants, shops and easy access to all 18 new platforms. Access below ground via the London Underground is provided from directly from the Viking and Northern Lines, with indirect access from Euston Square on the Circle and Metropolitan Lines (*1).

Birmingham New Street forms the intermediate station in the West Midlands. A partly bombed out wreck resulting from damage during the Second World War, it staggered on through until the mid 1960s when a rebuild began. The station was shrunk down to 10 through platforms serving both sets of routes; a ruthless cutting exercise, and freeing up space to the south side of the station for additional shops and retail area. The recent formation of the West Midlands PTE (marketed as "Midline") has spurred the creation of the first cross-city line, and resulted in the reconfiguration of the station; 6 longer-distance platforms, and 4 short-distance Midline platforms on the southern side. The renovation of New Street has led to a service concentration on New Street station, with Snow Hill station hardly used now, following the finish of the West Coast electrification project - which also saw the opening of Birmingham International station in 1976 adjacent to the airport.

Manchester Piccadilly forms one of the northern termini of the route. Modernised in the 1960s too, and renamed from "Manchester London Road", the station was thoroughly redeveloped, and restoring the Victorian trainsheds. The opening of the new Piccadilly station allowed the sale (and subsequent demolition) of good sheds to the north of the station, and Mayfield station to the south side of the station. Piccadilly station itself, despite being the premier long-distance terminus for Manchester remains unconnected to the Manchester Metro network (due to open 1980) due to cost cutting and tunnelling difficulties.

Liverpool Lime Street is the other major terminus in the North-West of England - both accessible in approx 2:45 from London. Renovated prior to electrification too, the station is again unconnected to the urban rail "Merseyrail" network across the Mersey (as is Liverpool Exchange). Constant discussion locally continues over further construction of the urban network, especially connecting Lime Street to the network, considering the works which have occurred in Manchester, Newcastle and London, whilst Glasgow and now Birmingham have urban networks themselves.

Glasgow Central, like Manchester, is the premier station for Glasgow, serving all southbound routes. It is well connected to the Strathclyde Metro system, sited on both the South Tunnel and Subway lines, and also serves a wide array of suburban routes to the south of the Clyde from it's 13 platforms (following the closure of St Enoch station - now a shopping centre, although Queen Street and Buchanan Street stations on the north side both remain open), although several routes to the south-east of Glasgow were subsumed in to the Metro network. The station, being one of the few on the route not to have been renovated, is due for refurbishment in the 1980s with the upswing in long distance travel on British Rail's "Intercity" trains.

Edinburgh Waverley is the sole city on the route which has only one primary station in it's centre, following the closure of Princes Street station (although the groundwork and buildings remains in place and owned by British Rail rather than demolished due to disagreements with the local authorities. Although also the northern terminus of the East Coast Route from Kings Cross station in London (trips were slightly quicker using this route), Edinburgh also formed one of the northern termini for the West Coast Route services from Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester.

Mark 3 coaches on display for marketing in later years.

Rolling Stock for trains to/from London is often formed of a Class 77 locomotive, operating at up to 90mph, although often limited by the winding and tortuous route. These locomotives were ageing rapidly however; the rapidly evolving technology and new designs meant trouble maintaining them, and they were proving underpowered for the new generation of trains, with wheelslip during acceleration requiring careful attention by train drivers. Modification in the mid 1970s to enable multiple working using the RCH cables (TDM signalling) heralded the introduction of the fixed-rake Mark 3 coaches. Operating experiences with the early "Blue Pullman" fixed rake train illustrated the advantages of fixed rake trains, and although a full multiple unit was out of budget for British Rail who were still rapidly developing their "high speed rail" concept from London to the North and Channel, a semi-fixed rake coach set was clearly an easy half way step.