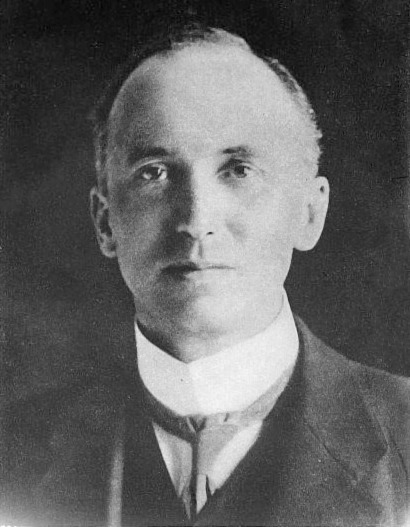

Sir Charles Madden, Royal Navy, 1923-1924

Sir Charles Madden, First Sea Lord

Royal Navy, 1923-1924

The Second in Command

Beatty’s death had, initially, been seen as a sign that the normal round of civilian leadership might begin again. The situation seemed calmer, with the ceasefire in Ireland roughly holding and trade picking up, but really it was clear that Britain was only in the eye of the storm.

The Liverpool Dock Fire of 1923, which started when lightening struck a warehouse full of cotton bales in the Docks area, spread across the city through the early hours. Fed by the vast warehouses of the Docks, it burned with amazing rapidity through the sleeping city. Some six hundred people died in the firestorm as firemen from across Merseyside struggled to battle the inferno as it consumed their city, and in the aftermath of the chaos the Home Secretary, Joyson-Hicks, activated local soldiers and irregulars camped nearby on their return from Ireland.

They were sent in to aid with the evacuation and fire-control but, with martial law declared in the city, some Black and Tans who had been engaged in getting steadily drunk that evening, took the opportunity for a little vengeance on Irish and “Bolshevik” civilians. As many as 93 Irishmen and women, trade unionists, and even Labour MP David Logan “vanished” during the clear-up that night. Despite a vigorous Parliamentary enquiry in 1925, no clear evidence of military or police involvement was uncovered until the post-war years.

George V’s decision to rely on a second military figure to step-in was born out of this terrible catastrophe and also the tipping over of the French General Strike into open revolution later that month.

Sir Charles Madden, Admiral, was Beatty’s second in command and his replacement as First Sea Lord. Madden was a career seaman who had initially taken to the sea at the age of thirteen as a naval cadet and many feared he would know nothing outside of ward-room life.

Yet Madden’s short-lived administration proved remarkably positive on many levels. A traditional Edwardian Liberal, Madden inspired confidence if not deep affection or commitment. He helped push through female suffrage legislation, arguing that it would provide a “sensible bulwark” to radicalism, demobbed much of the army and the entirety of the Black and Tans, and generally laid the foundations for a return to civilian leadership in Britain. Largely relying on Beatty’s former cabinet, though, proved his undoing as his Government was unable to shake the taint of the Liverpool fire that attached itself to Joyson Hicks and other ministers who took the reins during that fateful night.

Although Madden fixed elections for June 1924, his premiership almost did not last to see them arrive, as the attempted assassination of the Prince of Wales by a deranged young gunman claiming to be a member of the “Communist Party of Great Britain” saw public confidence in his leadership collapse. Even though Prince Edward was fine Madden felt obliged to offer his resignation to the King nonetheless, but George V refused until the outcome of the election was clear.