FOR WANT OF THE HAMMER

THE WOE OF AFTERMATH, 648 AVC

THE WOE OF AFTERMATH, 648 AVC

The carrion birds circled overhead, swooping closer and closer, descending down toward the ground, until they alighted upon some twisted limb or a raised head, and began to feast. The Germans, so numerous, had taken some hours to sift through the Roman items and take what they wanted, and the sound and physical presence of thousands of walking, talking men had driven the birds away until their departure into the hills. Now no man moved, and the birds feasted; the stench drew their fellows from far afield.

The shadows were lengthening and the sun preparing to duck behind the hills when Marcus Livius Drusus came awake. The dull ache of his head had interrupted his sleep and now he looked about himself, neck creaking in protest. He gritted his teeth and tried to sit up, but the effort brought a rush of blood to his head that made him grunt in pain and lay back down. Water. It was his only thought, to get to water. He saw the twisted bodies and smelled that gut-turning stench, but those stimuli had little effect on him. More awake now, eyes rolling and dry tongue filling dry mouth, he sat up.

He screamed with the pressure it put in his head, and he heard some bodies near him shifting. Somebody else. Somebody else alive. How had he fallen? He remembered shuffling and fighting and shouting along with his men, a succession of images—the man next to him getting his arm chopped off, a German slipping in the jellied mud and getting stomped on, a six-foot pale mass jumping at him with upraised swords, crooked brown teeth spitting words in a harsh language.... Drusus stood quickly, knowing that he had to do it that way, and swayed on his feet. All right, all right—he retched, bile filling his throat and mouth and dribbling down his chin and neck and armor. He leaned forward, spitting out as much as he could; it hadn’t done anything to help his dry mouth.

Swaying on his feet, he looked around. He was the only one up. The Roman bodies were strewn all around him, a few missing helmets or cuirasses, and with no Germans in sight; they’d taken their dead, as always before. How had they lost? Water! In the distance but not too far away—maybe half a mile, he judged—was a water donkey. He began a shuffling walk toward it, aching legs and shoulders protesting at every step; the battle had lasted hours, and he’d had no proper rest. As he passed one cohort he heard a particularly alive groan off to his left, and he stepped as gingerly as he could over a few bodies to find Quintus Caecilius Metellus propped up with his arms to the size, atop a few dead bodies. “Drusus,” sighed Metellus.

“Piglet,” Drusus dropped to his knees and hugged his friend close. “Oh, oh my Gods.”

“No talk,” whispered Piglet. “Water.”

“Water. Get water, then be back,” Drusus nodded, standing again. He felt only a bit stronger now, but he knew how desperate his situation was. He was the only standing man among a few hundred—maybe even a thousand—wounded, and he needed water, and he needed food. But the Germans would have taken all their food, how would he get everybody out alive? His jaw set; some would die here crying for water, or for their mothers.

He got to the unmolested donkey, which hadn’t fled only because it was still tied to the dead noncombatant’s arm. It had tried to pull away, though, and the rope dug into swollen rotting purple-black flesh. Now it stood placidly, very happy to see a living man; Drusus untied it from the man’s arm and tied it to his own, so that the donkey would stay if he fell. Having thus secured it, he took a skin of water from the sack at its side, tearing it open and sucking greedily. The cool, clean water flooded into his mouth and throat like a river through the desert, unsticking his tongue from the rest of his mouth and washing the acid down back into his stomach. He drank and drank until his stomach was distended; then he stopped and swayed, belching.

After three belches it came up in a tide, and mostly clear, warm fluid cascaded onto his sandals. Groaning, he crouched and retched again, until all the water was out of him. “Better,” he groaned and, standing and unstoppering another skin of water, took slow sips. “Much better.” Though he was wounded and addled he still remembered his directions, and headed right back to Metellus. “Drink slowly, or else it’ll all come back up,” he said hoarsely.

Piglet heeded him and was soon able to stand. He too had gotten a head wound, though it had been glancing. “Cato chopped the man’s arm off as he hit me,” he explained, “I saw it.” They were standing there, where Piglet had lain, not quite sure what to do.

“Where’s Cato now?”

Piglet pointed to a body that had been laying close to his own; Drusus turned it over and saw the open grey eyes and wavy brown hair of Cato. Below that the young man’s face was an open, angry red gash split from ear to ear by a sword. Drusus put two of his fingers on the man’s eyelids and pushed them down. “Poor lad.”

“We were on the left, we got the main charge.” Piglet had begun walking to the right. “More should be alive to the right.” Drusus, without a better idea, followed him. Most of the men they found were too far gone, out of horrendous wounds or too long without water, to be revived; most of them wouldn’t make it. They picked their way through the carnage with the donkey following. After a while Piglet stopped; they were about where the center of the line had been. “I feel as though I’m being watched.”

Drusus looked around and gave a heavy sigh. “There.” Two crossed eyes stared at him from in between the tangled limbs of two bodies; it was Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo Vopiscus, dead as death. Holding his hand was big brother Lucius Julius Caesar. As they neared the right of the line they heard a peculiar noise akin to the sound of the wind around a tent at night. “What’s that.”

They went on as it got louder and louder, and then saw four limbs flailing weakly in the air, almost hidden by bodies. They picked their way there as quickly as they could and dragged the bodies off. It was Sextus Julius Caesar, who had the wheezes, with no nose, half his chin gone, a horrific bruise spreading over his face, and a mouthful of blood. The yellow hair was dark and plastered to the brow with sweat and the blue eyes stared out consciously and with intelligence; he knew exactly what was happening.

“My Gods, that’s not a bruise; his face is purple from wheezing,” said Drusus. Caesar nodded, looking wildly from one man to the other and then doubling over in pain; the pain eased and he resumed with the flailing limbs.

“So much pain,” Piglet said in a choked voice. “He can’t live like this, he won’t survive.” After debating for a while and deciding who should do it, Drusus volunteered. When it was over, Piglet said, “There. One battle and now there’s only one Julius Caesar of our generation.”

Drusus shivered. “I’m the only Livius Drusus of my generation.” To this Piglet had no reply, and they walked on.

“It’s cold,” said Drusus, shivering; the sun had disappeared behind the hills and shadow was covering everything. At least it was a full moon, and they would for the most part be able to see. “We’ve got to find whoever else can walk.” Because of how wide the line was, they missed quite a few men on their first pass, and even on their next few passes; now they found Lucius Aurelius Cotta, who could walk but whose left elbow had shattered, and Gaius Claudius Pulcher, who had taken a sword to the ribs. Luckily for Pulcher, the linen tunic he’d been wearing had been driven into the wound and had staunched it very well; still, Drusus could feel little bits of rib moving about as he inspected the young man.

Now the going went slow, for every step took Pulcher an eternity of main and ragged breathing to complete, and they finally reached the left end of the field again. “Oh oh oh,” shivered Cotta, trying to hug himself and moaning when the crushed bones of his elbow grated together. “I’m cold.”

“Let’s go back to the camp,” sighed Drusus dejectedly, disappointed that he’d only found four men alive, and none of them centurions. “We might find food and cloaks there.”

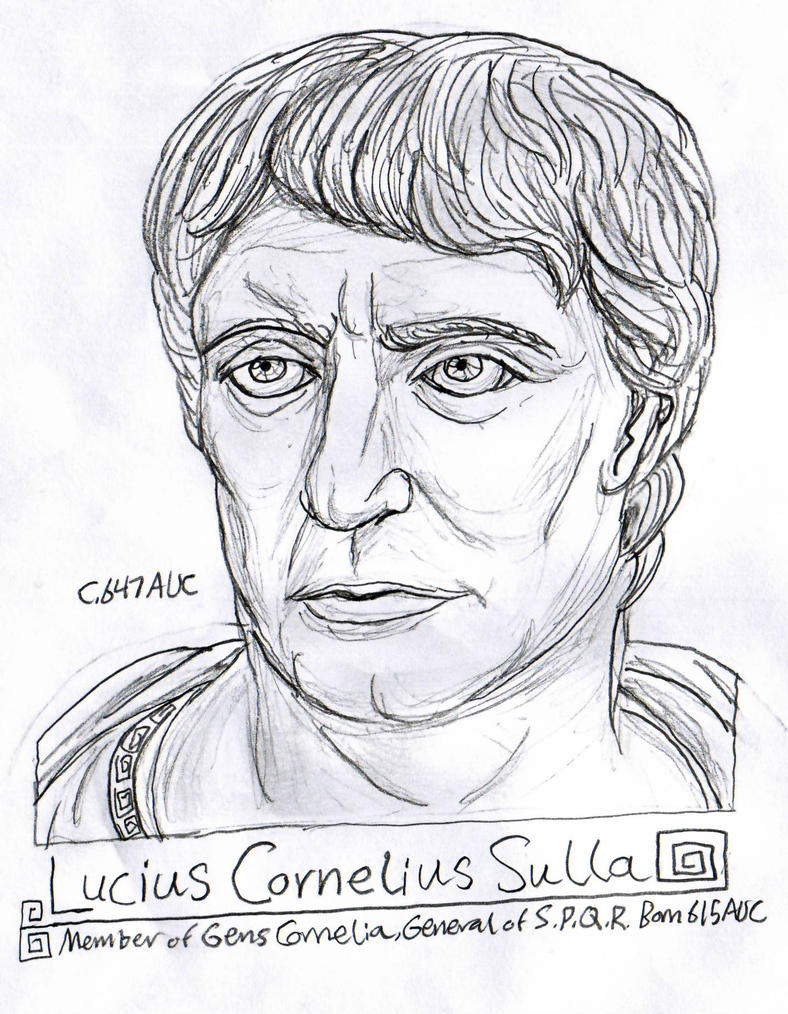

They turned and began to trudge up the hill when suddenly Drusus saw a form lying at ease, as if sleeping, on the ground. Its face was pale, as if reflecting the moonlight, and its hair of golden fire spread out about it like a halo. “Lucius Cornelius!” Drusus jogged forward, pulling the donkey with him, and bent down. Sulla breathed slowly and deeply, and didn’t seem to have a head wound; he truly looked as though he was sleeping. Drusus shook him, trying to wake him up, but his head lolled left and right and jostled up and down. Piglet knelt and felt his brow.

“That’s one bastard of a fever,” he said grimly. Drusus put his hand there and drew it back almost immediately. “Ow, that’s hot.”

“Well, what’s wrong with him?” asked Cotta.

Piglet undid his cuirass and pointed at a hole just under Sulla’s ribcage and aligned vertically with his heart. “Looks like a spear passed clean through him,” he sighed. “I doubt any doctor’s see a man survive this; it’s through his liver.”

“Lucius Cornelius will survive it,” said Cotta. “He wants to live too much, he’s different.”

Piglet turned to stare at Cotta. “Lucius Aurelius, this kind of wound...a man just doesn’t survive it. It just won’t happen.”

“He’ll survive it,” said Cotta willfully. “The Gods won’t let him die.”

Piglet turned his head to stare at Drusus. After a while Drusus shrugged. “If he lives, all the better for us. Come on Piglet, we’ll carry him to open ground, and then we’ll make a litter.”

So uh yeah having the flu and a 103.4 degree fever sucks. I couldn’t concentrate enough to write, so I’m sorry about that. What do you all think of this update? Too garbled? Too rambling? That’s sort of my opinion of it; oh well.