tuareg109

Banned

It was only just mid-morning, and Gaius Marius and Publius Rutilius Rufus were already finding it hard to contain their boredom. They had made several rounds of the camp after morning assembly and drill, and then again after their small breakfast of porridge. Then they'd seen Quintus Catius up on one of the towers, and joined him to look down into Numantia.

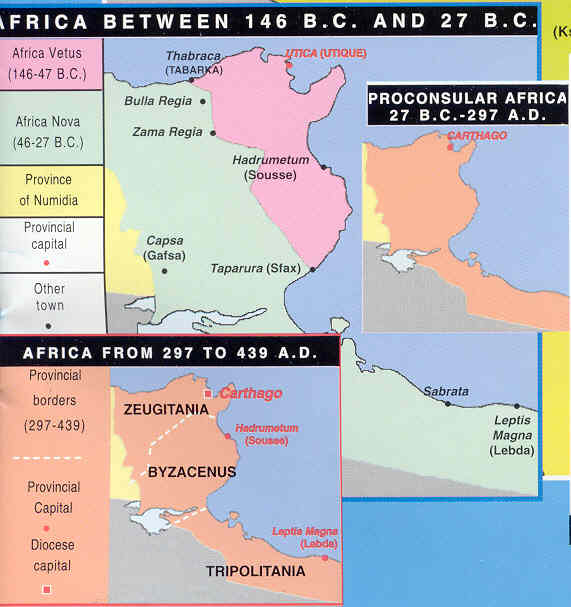

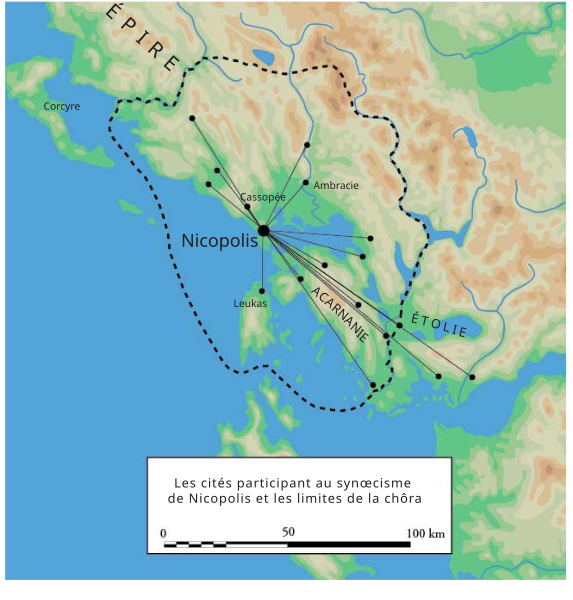

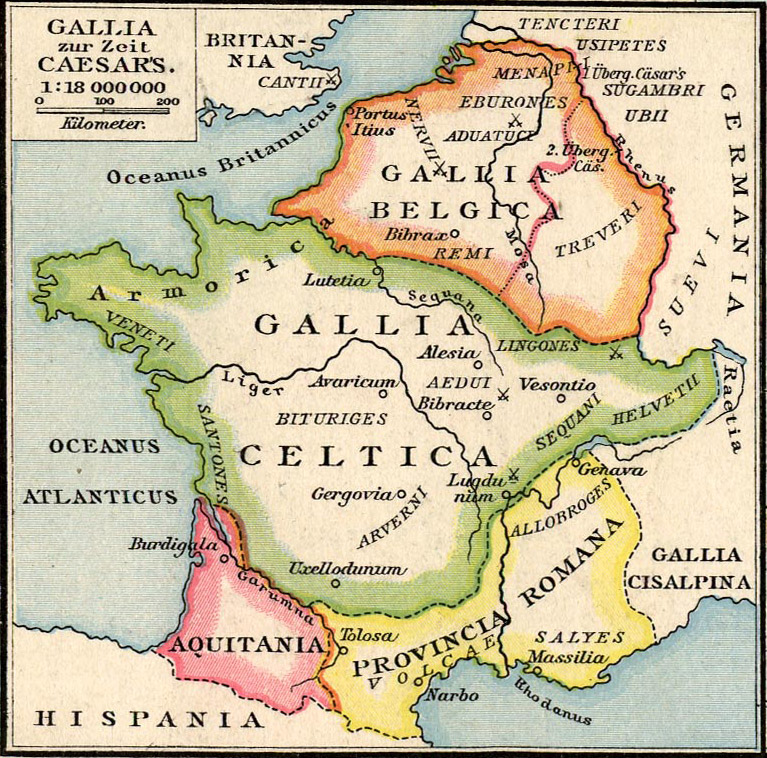

Grey arrows indicate Scipio Aemilianus's campaign against the Celtiberians, 619 AVC

The city had been--and certainly still was--an eerily quiet place. No cries of merchants or curses of men and mothers greeted the Roman ears; there was nothing to sell, and mothers clung children tightly to their breasts indoors, fearful of Roman arrows.

Since their commander, the Proconsular governor of Hispania Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus Africanus, had completely circumvallated the city, the Roman ballistae could fire bolts a quarter of a mile into the city--far enough to reach the center.

Marius shivered as he remembered the first time he'd seen one used--fired into a solid, seething crowd in the town square, enough worn out by hunger to attempt a break out. The bolt had gone through five men and pinned them to a stone building, all a quarter of a mile away.

Thus Marius had been profoundly grateful that the only people visible in Numantia were darting quickly from house to house on some business or other, and that Quintus Catius and his colleagues on the siegeworks hadn't had to use their weapons today.

And yet, it didn't make the boredom easier. More than enjoying direct, open battle, Gaius Marius reveled in it. He didn't enjoy the blood, the screams, the suffering, and the death; however, that was all Fortuna's say, and he would not stop her from taking what was hers.

No, what Gaius Marius loved was the line, the rank and the file, the command given out and obeyed; he enjoyed more than anything the bugle calls. Watching a battle from a hill--which he'd done only once, as a Military Tribune green to command--he'd seen it all fall into place. The superb organization of the armies of Rome; the moving caterpillar of the barbarian lines, men more likely to strike their own comrades than Roman necks.

Here, this, was what he was born to do. And he'd fallen into it with a fervor that had pleased Scipio Aemilianus immensely; here was a subordinate who did his job purely. There was no grovelling or brown-nosing or malingering from Gaius Marius; the young man was simply dedicated to his beloved work.

And, now that he had no work cut out for him, life in the siegeworks was becoming boring. Brief, early afternoon forays to the other side of the cavalry camp for a gallop with Publius Rutilius and young Prince Jugurtha, or to the Durius upriver of Numantia--to avoid the odium of dead Celtiberian bodies and fecal matter--didn't quite cut it for Gaius Marius. As an elected Military Tribune he had command, of course. The only problem was that, during a siege, there were really no commands to issue. The siege continued until such a time as the situation changed.

Gaius Marius had even appealed to Scipio Aemilianus, who had stoutly refused. "I understand your plight, Gaius Marius," said Scipio Aemilianus one of the many hot, dry summer afternoons in the hills. No aristocratic drawler, Scipio Aemilianus was so patrician on both sides--birth and adoptive, patrician squared!--that Gaius Marius the country bumpkin's son from Arpinum was of the same social standing in his eyes as the long-ennobled Plebeian clans; simply, Scipio Aemilianus wasn't interested in basing his opinions of others on birth and class. So he treated Gaius Marius as his merits and intelligence demanded: kindly and with respect.

"I understand your plight, but you must understand that we are at war. Any siege can be a boring business unless you're one of the more enthusiastic engineers, and yet battle--through sally or relief or trickery in the day or night--can break out at any time. We must be prepared, and that means having our best young men available to lead. I'm proud to say that you're the foremost among them."

Gaius Marius had sighed and said not without respect, "Yes, Sir. I'll limit my outdoors activities."

Scipio Aemilianus had nodded briskly and smiled. "You do that, excellent. And invited Prince Jugurtha of Numidia to your forays; though not Roman, he's an excellent young man that we should hope to bring into the fold." He then watched Gaius Marius leave quickly--well, everything a natural soldier did was quick and efficient--and then dropped his eyes to the Senate dispatches he'd been perusing.

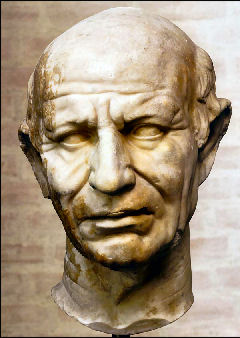

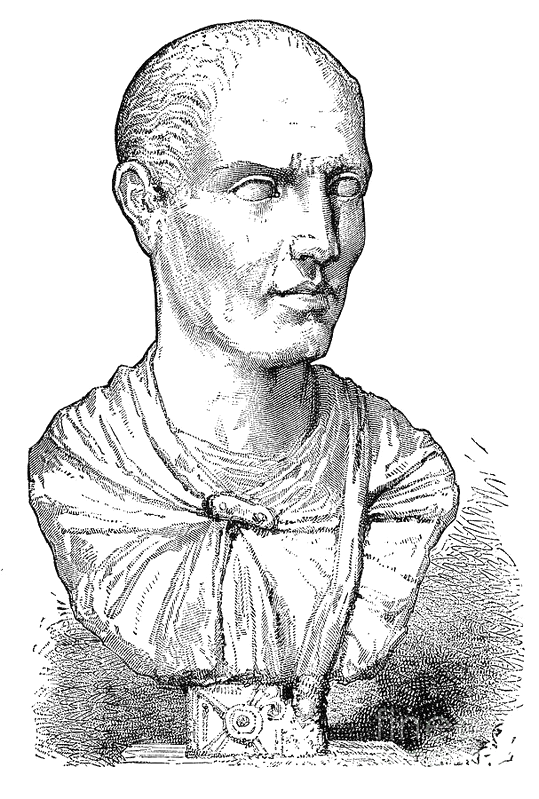

Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus Africanus, commander of the Siege of Numantia

And so Gaius Marius and Publius Rutilius Rufus were rounding the city again when Publius Rutilius stopped in his tracks, then half-ran to catch up to Gaius Marius.

"Huh? What is it, Publius?"

"Nothing nothing, an itch."

Gaius Marius gave Publius Rutilius a skeptical glance, and backtracked a few steps. He knew when his friend was trying to keep them out of trouble. Publius Rutilius rolled his eyes and waited for the worst. Gaius Marius broke out into a smile and whispered "Aha, there he is!"

Quintus Caecilius Metellus leaned against the duty officer's table by the camp gate talking to that same duty officer, Marcus Junius Silanus. Both were plebeian nobles of ancient lineage, and both viewed Publius Rutilius as an upstart, Gaius Marius as a peasant nobody, and Jugurtha as a third, far worse, element--a barbarian!

Gaius Marius's teeth gnashed when he saw the two of them, thick as thieves and stuck with easy jobs with no responsibilities--according to their merits, of course! And yet they would likely rise higher in the Cursus Honorum that Gaius Marius ever would, solely due to the names of their fathers. Gaius Marius had a personality that bordered on abrasive, and he liked to showcase it; tall and big and blustering, with wide shoulders and bushy black eyebrows, Gaius Marius could probably push through life by being abrasive, all the way to the top job.

Publius Rutilius Rufus's teeth gnashed when Gaius Marius's did, but not for the same reasons. Publius Rutilius couldn't help but follow the young man his own age around; the charisma, the brain, the ambition! Gaius Marius's loud approval of the politics of Tiberius Gracchus attracted Publius Rutilius in every philosophical way. The only catch was the consequences.

Publius Rutilius too had his own share of ambition. His father had been a Tribune of the Plebs; his grandfather a Novus Homo who had become Praetor. The gens Rutilia had barely any political allies, and no stalwart allies-by-marriage, to speak of. Were Publius Rutilius Rufus to incur the enmity of the vast Caecilii Metelli clan, or the less widespread but more ancient Junii, his family's line in politics--begun so doggedly and with such hard labor by his grandfather Publius--would be over. So Publius Rutilius Rufus tended to tread carefully and get butterflies in his stomach when Gaius Marius concocted a storm of casual insults to Quintus Caecilius Metellus.

So Publius Rutilius Rufus had no choice but to follow Gaius Marius with every misgiving, and see him march up to the duty officer's table and slam his large hands flat on its top. Quintus Caecilius Metellus blinked and half-stood, whereas Marcus Junius Silanus--made of duller stuff still--opened his mouth and looked up. "What do you want?"

"Is that the proper formula, soldier?" Marius barked, and all conversations within fifty feet stopped at once. "I don't care if your daddy had to grovel at Scipio Aemilianus's feet to get you personally appointed; I was elected by the Roman people, and as such I will be respected!"

Marcus Junius gulped back his anger--still too confused to become fully formed--and began "What's your busi--" when

"Come off it, Gaius Marius!" Quintus Caecilius Metellus barked after his blinking attack in as loud a voice as Marius's, if not so deep. "You come barging in here, disturbing the peace with your atrocious Latin, and expect to be respected? Turn around and approach with consciousness of your station--as a peasant Samnite supplicating to a noble Roman." And Quintus Caecilius delivered a sweet smile onto both Gaius Marius and Marcus Junius--sarcastic in the first case, and supporting in the latter.

Marcus Junius took the hint and continued the argument, as men began to slide closer and crane their necks to see. They were soldiers without a battle, and any conflict pitting the popular Gaius Marius--of similar origin as many of them--against the haughty and--to them--worthless Quintus Caecilius was worth watching. The possibility of a real, physical fight was even better.

"Gaius Marius," said Marcus Junius softly--which was oddly enough his tone when any situation became serious, "please come back when you are fit to report. You are either drunk or sunstruck. Why not swim naked in the river with your barbarian friend?" Though the word barbarian used by many men was simply descriptive, the use of it by this particular Junius in any tone indicated insult.

"You call me a peasant," Gaius Marius picked up loudly, "and my good loyal friend a barbarian! Well, you're just a couple of heavy-handed light-headed pippina! I doubt that you have the brains between you to organize a dinner party for one!"

"You'd know," said Quintus Caecilius wistfully, "about dinner parties." Reminiscently he added, "Wasn't that your father who sold us that lamb for my cousin's marriage party, in the Boarium? I was fascinated with the brutishness of the man, being only a child and ignorant of such filth, and so I followed him to a whorehouse, where your mother led a child about my age with your coloring, and your eyebrows, and your name, and I thought--"

Whatever Quintus Caecilius had thought was interrupted. He had been gazing up at the clouds as if remembering a glorious event, and didn't see Gaius Marius's body dip a little as his legs compressed into springs--and launch himself into Quintus Caecilius. They tumbled into poor Marcus Junius the duty officer, and became tangled in the dry-packed dirt of the camp. Men rushed in from all sides--mostly to watch. Publius Rutilius, being of average physique himself, didn't have the muscle to muscle through the first responders, who were busy betting on the outcome, which was heavily in favor of Gaius Marius.

He didn't see big, sleek Jugurtha--an inch taller than even Gaius Marius, who was quite tall for a Roman--crash through the crowd, which was thinner from the gates. For the Numidians in their cavalry camp just outside the gates had heard the yells, and Jugurtha had been among the first to notice. His pale blue eyes--striking and ominous in the dark Berber face he had inherited from his mother--moved men more efficiently than shoves. He dived under the table like a panther, in full equestrian gear, and didn't stop moving until Gaius Marius was struggling against his one strong arm and Quintus Caecilius down on the ground under the other.

"Stop this Gaius, you idiot! Don't you know the damage you're doing?" He locked eyes then with the onlooking Publius Rutilius, and managed a rueful and knowing grin, which was returned.

"Idiot, is it? Why you, you...!" Gaius Marius whipped up into a frenzy--by himself or by any other man--took some time to cool down.

What did calm him down, and rather quickly too, was the sound of hoofbeats from inside the camp. Only the most official messengers and the most senior legates were allowed horses inside the infantry camp. That meant--

"You! All you men! Disperse, go back to your discussions," Scipio Aemilianus said in loud, clear, angry Latin. The assembled men stared up at him for perhaps two or three seconds, before quickly turning and striding back to their positions. They knew enough not to incur the wrath of this legendary commander.

"You! All you idiots! You absolute women! To my tent, all of you." He said this all in Greek, so that for the most part only Jugurtha and the Military Tribunes understood.

Several hours later it was a bit past noon.

Quintus Caecilius Metellus and Marcus Junius Silanus had left with their pride smarting--and not much else. They had, after all, only reacted to rudeness. And though all the soldiers had asserted that it was Gaius Marius was in the right, Scipio Aemilianus had come to distrust the rankers when it came to their opinion of Gaius Marius.

Publius Rutilius Rufus had left with the lesson that he should have acted sooner, and an apology to the bruised Quintus and Marcus. Without Gaius Marius's presence in the room, his apology was much more sincere than it could have been.

Prince Jugurtha of Numidia, all of twenty three years old, was commended for breaking the fight up, and yet advised to leave Roman conflicts to Romans in the future. He left with an annoyed look at the last man waiting outdoors under the hot sun: Gaius Marius.

Gaius Marius marched in after the smirking duty officer called him in. It wasn't that this young officer--also about Marius's age--named Spurius Dellius took any side; the whole issue was simply hilarious to him. Gaius Marius smirked back and raised his hand as if to slap Spurius, but the other young man only barely contained his giggles, rolling his eyes and weakly waving the equally amused Gaius Marius into Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus's presence.

Scipio Aemilianus knew very well what Gaius Marius's potential was, and knew very well that the middle course must be steered to bring him there. Antagonizing the powerful Caecilii Metelli would bring ruin onto Gaius Marius; passively accepting his place allotted by society would prove equally ruinous. Scipio Aemilianus was a patriot, and what he wanted most of all was to mold this brilliant young commander with potential in both soldiery and lawmaking into the best he could be, for Rome's sake.

He had to confess that he didn't like the haughty plebeians like young Quintus Metellus and Marcus Silanus much; he liked them even less than haughty men of his own impeccably patrician background, for these young plebeian men couldn't even claim to be descended from the Republic's forefathers, or ancient kings in Latium or Etruria or Campania.

So Scipio Aemilianus had decided to speak to Gaius Marius last, with his rage at this childish display ebbing.

"Sit, Gaius Marius." Though it was said sternly, Marius noted a hint of tiredness. Dealing with our foolery must drive him mad, thought Marius. Well, at least it's something to do in this forsaken place.

"Yes, Sir," Gaius Marius said, and sat.

"I recall that I said before that I understand your boredom." Without a pause for effect, Scipio Aemilianus continued. "I do not, however, understand your behavior today. You show a lack of maturity, intelligence, and command--yes, I said command, don't give me those silly doe eyes--command of your senses and your emotions." Now he paused for effect, giving Gaius Marius the time to reflect that he must be quite angry. His usually florid speech had given way to very simply oratory. Gaius Marius sat up straighter, dreading what might come.

"I am not," said Scipio Aemilianus sternly, "ejecting you from this army. I'm not even going to punish you." Gaius Marius's caterpillar eyebrows flew up and began to undulate curiously; after tearing his eyes off of them, Scipio continued, "You need a healthy diversion to develop your sense of who you are. You need some time away from the isolation and violence of this camp. You need a command in which you make the decisions."

The eyebrows stopped and Gaius Marius's ears perked up. Now it was Scipio's turn to raise his eyebrows, and Gaius Marius breathed, "Please continue, Sir." It was a dream come true.

"Oh, it's 'Please' now, is it?" Scipio cracked a smile. He dived into the job without further preamble: "You're to take a century of men downriver, to the ford crossing the Durius about three miles away. You will relieve the force of Aulus Egilius, who has been holding the crossing and watching for Numantian siege-dodgers swimming down the river. You'll be taking the Fourth Legion's Twelfth Century, under Centurion Gaius Corfidius. Yours will be all the ultimate executive decisions, but I expect you to fully use the advice of Gaius Corfidius and his Optio Lucius Potitius Gallus; they are both very experienced."

"Sir...I...THANK YOU!" Gaius Marius burst out. As a Military Tribune, he hadn't expected to see any independent command; that was for the more intelligent and ambitious Centurions. He hadn't expected any independence until becoming a Propraetor and governing a province--whenever that might have been. Now here was his chance to prove himself.

Scipio's tight smile betrayed his pleasure at Gaius Marius's combined pleasure and disbelief. "Run along now, Gaius. Corfidius and Potitius were informed as soon as I made my decision about what to do with you--just before seeing Quintus Caecilius after this morning's events." Now the smile faded. "Any more silly antics, Gaius Marius--and I mean it!--and I'll have to remove you from command. You're better off staying a country squire in Arpinum than drawing the enmity of the Caecilii Metelli in Rome."

Gaius Marius swallowed and nodded. Quintus Caecilius was insignificant now, a flea, now that Gaius Marius had his command. "I won't let you down, Sir."

A bust commonly held to be of an older Gaius Marius

Yay, my first TL! What do you all think of this first part of the prologue?

Please point out any stylistic or grammatical mistakes or inconsistencies; I won't have it in others' writing, and I'd appreciate an utter lack of it in my own.

Kudos to whoever can guess the POD (not yet arrived)!

EDIT: In hindsight, some may not know what AVC means. AVC means Ab Vrbe Condita, or Ab Urbe Condita; After the Founding of Rome.

1 AVC is commonly held to be 753 BC, so 619 AVC is 134 BC.

Last edited: