[FONT="]Why hello there. This is a re-start of my timeline, Is Rome Worth One Man’s Life?-A Roman TL. Some of you who have been following the other timeline may be wondering why I restarted it. Well, after researching and reading further into the time and the character of Sextus and the other characters, I realized I really was not being accurate and a lot of my stuff was not realistic. In addition, I had left out some key events that I tried to fill in after the fact, and I did not feel I was doing the timeline justice. It just wasn’t very well researched on my part. Hopefully this time around I can do it a lot better. At least in the beginning, I should be able to update this timeline rapidly, as I know where I want to go with it at least initially Without further ado…

[FONT="]

[FONT="]

[FONT="]

[/FONT][FONT="]At first Cicero showed signs of his trademark indecision, unsure whether to join the Liberators, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus in the east, or remain in Italy. Luckily, his respect and sympathy amongst the populace was such that only a small few dared to even admit they had seen the legendary statesman. Finally, with the help of friends, Cicero left in the midst of a large crowd from his villa in Formiae, on December 5th, 43 BC. [1]Joining him was his only son, Marcus Cicero Minor, along with his brother Quintus and his son, Quintus Cicero Minor. When he reached the seaside, he embarked on a ship bound for Macedonia, with the intentions of meeting up with Brutus and Longinus. [/FONT]

[FONT="]

[/FONT][FONT="]Things began to go awry soon after the ships departure, as the ship was caught in a storm. It was only due to an experienced ship belonging to the navy of Sextus Pompeius, another enemy of the triumvirate, happening to be in the right place at the right time that the ship and her crew, including Cicero and his family, were rescued. The crew was shocked to see that the great Marcus Tullius Cicero was also on the ship, to which they thanked Neptune for sparing the prestigious senator. It was not long before they reached Pompeius's stronghold base of Sicily, from which an envoy was immediately dispatched to inform the young leader of the unexpected arrival of one of the most influential men of Rome. [/FONT]

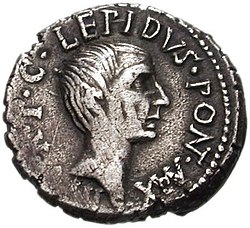

Sextus Pompeius on coin with his father

[FONT="]Sextus Pompeius was the new Republican maritime leader that emerged in Sicily, complimenting Brutus, Cassius, and Ahenobarbus in the east. The Republican cause was at its most prosperous point, as they controlled the rich (both in money and manpower) eastern provinces as well as having complete domination of the seas, thanks to Ahenobarbus and Pompeius. The young man-he was merely 18- was never supposed to be in such a position of strength. His career was as much unorthodox as his father’s, the great Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Whereas his father started out his career with an unbroken string of successes and a rapid rise to supreme command thanks to Sulla, the Sextus’ early career was defined by hardship and violent turns of fortune. [/FONT]

[FONT="]In 48 BC (during the climax of Caesar’s Civil War) at age 19, Pompeius was sent on Mytilene on the island of Lesbos in the north of the Aegean Sea. Here, his father would be content knowing his youngest son was safe from the fighting between himself and Caesar. When Pompeius Magnus was crushed at Pharsalus however, he fled to Egypt with the hopes of raising a new army, taking Sextus along with him for the trip. It was in Egypt, that Sextus witnessed the murder of his father, an event that changed his life forever. [/FONT]

[FONT="]When Pompeius Magnus’ boat approached the shore, he was greeted by a soldier by the name of Lucius Septimius[2]. Pompeius turned to both his wife Cornelia and Sextus, kissed them, and uttered a phrase from Sophocles, [/FONT]

[FONT="]Whoever makes his journey to a tyrant’s court[/FONT]

[FONT="]Becomes his slave, although he went there a free man.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Sextus and Cornelia soon came to see how prophetic those words were. His father boarded a smaller boat, and just as he was about to step ashore, Septimius drew his sword and struck the un-prepared Pompeius in full view of the welcoming party on the shore, and his family further back on the sea. There was a loud cry on the ship that could be heard from the shore, but there was nothing that could be done, and the crew of the trireme quickly set sail away from any potential danger. [/FONT] [FONT="]The impact this had on the young Sextus’s life was huge. The greatest man in Rome, his father, had been dishonorably struck dead by an ambush of ruthless and cold hearted opportunists. Sextus from that point forward modeled himself after his beloved father, adopting the Agnomen “Pius” to convey his loyalty to the memory of Pompeius Magnus. Although Cornelia soon returned to Rome, the flame in the young teen had been ignited, and Pompeius joined his elder brother in Africa. Soon after, the republican forces were defeated at Thapsus, and the two Pompeian brothers fled to Africa with the talented Titus Labienus to Hispania, where the Pompeian name carried a lot of weight with the people. [/FONT]

[FONT="]It was not long before Caesar arrived on the scene in March of 45 BC. On the 17th of that month, the republican army was destroyed at Munda, where Labienus died honorably in battle, fighting for the defense of the republic until he could fight no more. The two brothers soon found themselves on the run, and it wasn’t long before Gnaeus was hunted down and executed. Sextus however managed to keep on the run in the Iberian hinterlands, and although pardoned by Caesar who deemed him too young and inexperienced to be a threat, remained at large, and soon gathered an army, leading an extremely effective guerrilla campaign. With the help of the Iberian tribesmen, the young Sextus soon learned to master the arts of guerilla fighting. In the grand scheme of things however, he was nothing more than a minor nuisance to Caesar despite his taking of many small towns and cities. [/FONT]

[FONT="]Then came the Ides of March and the assassination of Caesar by the liberatores. The next year, in 43 BC, the 24 year old Sextus was named prefect of the fleet and seas, and soon sailed to Marseille. It wasn’t long before Caesar’s political and private heirs formed a triumvirate legalized by the Senate, and posted their proscription list. His position was revoked, but Sextus was not about to lay down his command. He soon convinced the governor of Sicily to hand it over to him, and went to work turning the island into a fortress, and building a fleet second to none. From Sicily he essentially controlled the grain supply from Egypt, North Africa, and of course Sicily. [/FONT]

[FONT="]When word arrived that the great Marcus Tullius Cicero and his family had arrived on the island, Pompeius could not have been more elated. He had always admired the talented orator, and immediately set out to meet him. Giving them as warm a welcome as he could on a short notice, Pompeius made sure to take time out the ensuing days to stop by and converse with the orator and his family. Everything about the young leader impressed Cicero, who claimed at such a young age he was already a better man than Antonius, Caesar, and Octavian combined. It did not take long either before Sextus struck up a chord with his son, Marcus Cicero Minor. The two rapidly became close friends, a relationship that would endure the length of their lifetimes. [/FONT]

[FONT="][1] IOTL, he left on December 7th, and was caught while leaving Formiae. [/FONT]

[FONT="][2] As far as I know, he has no relation to the emperor Lucius Septimius Severus[/FONT]

[FONT="]Most of the stuff on Sextus Pompey described here is from Antthony Everitt's "Augustus". Though he seems to have gotten his age wrong (he would not be 13 in 48 BC if he was born in 67...)

[/FONT][/FONT]

[FONT="][FONT="]Chapter I: Cicero's Exile[/FONT] [/FONT]

[FONT="]

]

[/FONT][FONT="]

-Marcus Tullius Cicero

[/FONT] Of the men proscribed by the Second Triumvirate between Octavian, Antonius, and Lepidus, Marcus Tullius Cicero was one of the most viciously and doggedly hunted down. Cicero aligned himself with the young Octavian after Caesar's assassination, even helping him convince the Senate to declare Marcus Antonius an enemy of the state. When Octavian and Antonius put aside their differences however, and formed the Second Triumvirate along with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, they created a long list of proscriptions, similar to those created only a generation a before by the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Antonius made sure Cicero was on the top of that list. [FONT="]The reason being, Cicero loathed Antonius, and Antonius in turn loathed Cicero. After the assassination of Caesar, Cicero made it a point to return to politics just to bring down Antonius. His collection of speeches known as The Philippics after the fiery Athenian orator Demosthenes speeches against Phillip II of Macedon, was solely based on attacking Antonius at every chance. Antonius had yet to get over those attacks on his character, and was eager to silence the great orator once and for all. No matter how much Octavian seemed to protest, Antonius was unyielding, even going so far as to place his own uncle on the proscription list just to see Cicero's name on it. Octavian had little choice but to grudgingly comply. [/FONT][FONT="]

[/FONT][FONT="]At first Cicero showed signs of his trademark indecision, unsure whether to join the Liberators, Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus in the east, or remain in Italy. Luckily, his respect and sympathy amongst the populace was such that only a small few dared to even admit they had seen the legendary statesman. Finally, with the help of friends, Cicero left in the midst of a large crowd from his villa in Formiae, on December 5th, 43 BC. [1]Joining him was his only son, Marcus Cicero Minor, along with his brother Quintus and his son, Quintus Cicero Minor. When he reached the seaside, he embarked on a ship bound for Macedonia, with the intentions of meeting up with Brutus and Longinus. [/FONT]

[FONT="]

[/FONT][FONT="]Things began to go awry soon after the ships departure, as the ship was caught in a storm. It was only due to an experienced ship belonging to the navy of Sextus Pompeius, another enemy of the triumvirate, happening to be in the right place at the right time that the ship and her crew, including Cicero and his family, were rescued. The crew was shocked to see that the great Marcus Tullius Cicero was also on the ship, to which they thanked Neptune for sparing the prestigious senator. It was not long before they reached Pompeius's stronghold base of Sicily, from which an envoy was immediately dispatched to inform the young leader of the unexpected arrival of one of the most influential men of Rome. [/FONT]

Sextus Pompeius on coin with his father

[FONT="]Sextus Pompeius was the new Republican maritime leader that emerged in Sicily, complimenting Brutus, Cassius, and Ahenobarbus in the east. The Republican cause was at its most prosperous point, as they controlled the rich (both in money and manpower) eastern provinces as well as having complete domination of the seas, thanks to Ahenobarbus and Pompeius. The young man-he was merely 18- was never supposed to be in such a position of strength. His career was as much unorthodox as his father’s, the great Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Whereas his father started out his career with an unbroken string of successes and a rapid rise to supreme command thanks to Sulla, the Sextus’ early career was defined by hardship and violent turns of fortune. [/FONT]

[FONT="]In 48 BC (during the climax of Caesar’s Civil War) at age 19, Pompeius was sent on Mytilene on the island of Lesbos in the north of the Aegean Sea. Here, his father would be content knowing his youngest son was safe from the fighting between himself and Caesar. When Pompeius Magnus was crushed at Pharsalus however, he fled to Egypt with the hopes of raising a new army, taking Sextus along with him for the trip. It was in Egypt, that Sextus witnessed the murder of his father, an event that changed his life forever. [/FONT]

[FONT="]When Pompeius Magnus’ boat approached the shore, he was greeted by a soldier by the name of Lucius Septimius[2]. Pompeius turned to both his wife Cornelia and Sextus, kissed them, and uttered a phrase from Sophocles, [/FONT]

[FONT="]Whoever makes his journey to a tyrant’s court[/FONT]

[FONT="]Becomes his slave, although he went there a free man.[/FONT]

[FONT="]Sextus and Cornelia soon came to see how prophetic those words were. His father boarded a smaller boat, and just as he was about to step ashore, Septimius drew his sword and struck the un-prepared Pompeius in full view of the welcoming party on the shore, and his family further back on the sea. There was a loud cry on the ship that could be heard from the shore, but there was nothing that could be done, and the crew of the trireme quickly set sail away from any potential danger. [/FONT] [FONT="]The impact this had on the young Sextus’s life was huge. The greatest man in Rome, his father, had been dishonorably struck dead by an ambush of ruthless and cold hearted opportunists. Sextus from that point forward modeled himself after his beloved father, adopting the Agnomen “Pius” to convey his loyalty to the memory of Pompeius Magnus. Although Cornelia soon returned to Rome, the flame in the young teen had been ignited, and Pompeius joined his elder brother in Africa. Soon after, the republican forces were defeated at Thapsus, and the two Pompeian brothers fled to Africa with the talented Titus Labienus to Hispania, where the Pompeian name carried a lot of weight with the people. [/FONT]

Battle of Munda

[FONT="]It was not long before Caesar arrived on the scene in March of 45 BC. On the 17th of that month, the republican army was destroyed at Munda, where Labienus died honorably in battle, fighting for the defense of the republic until he could fight no more. The two brothers soon found themselves on the run, and it wasn’t long before Gnaeus was hunted down and executed. Sextus however managed to keep on the run in the Iberian hinterlands, and although pardoned by Caesar who deemed him too young and inexperienced to be a threat, remained at large, and soon gathered an army, leading an extremely effective guerrilla campaign. With the help of the Iberian tribesmen, the young Sextus soon learned to master the arts of guerilla fighting. In the grand scheme of things however, he was nothing more than a minor nuisance to Caesar despite his taking of many small towns and cities. [/FONT]

[FONT="]Then came the Ides of March and the assassination of Caesar by the liberatores. The next year, in 43 BC, the 24 year old Sextus was named prefect of the fleet and seas, and soon sailed to Marseille. It wasn’t long before Caesar’s political and private heirs formed a triumvirate legalized by the Senate, and posted their proscription list. His position was revoked, but Sextus was not about to lay down his command. He soon convinced the governor of Sicily to hand it over to him, and went to work turning the island into a fortress, and building a fleet second to none. From Sicily he essentially controlled the grain supply from Egypt, North Africa, and of course Sicily. [/FONT]

[FONT="]When word arrived that the great Marcus Tullius Cicero and his family had arrived on the island, Pompeius could not have been more elated. He had always admired the talented orator, and immediately set out to meet him. Giving them as warm a welcome as he could on a short notice, Pompeius made sure to take time out the ensuing days to stop by and converse with the orator and his family. Everything about the young leader impressed Cicero, who claimed at such a young age he was already a better man than Antonius, Caesar, and Octavian combined. It did not take long either before Sextus struck up a chord with his son, Marcus Cicero Minor. The two rapidly became close friends, a relationship that would endure the length of their lifetimes. [/FONT]

[FONT="][1] IOTL, he left on December 7th, and was caught while leaving Formiae. [/FONT]

[FONT="][2] As far as I know, he has no relation to the emperor Lucius Septimius Severus[/FONT]

[FONT="]Most of the stuff on Sextus Pompey described here is from Antthony Everitt's "Augustus". Though he seems to have gotten his age wrong (he would not be 13 in 48 BC if he was born in 67...)

[/FONT][/FONT]

Last edited: