Those letters are adorable.

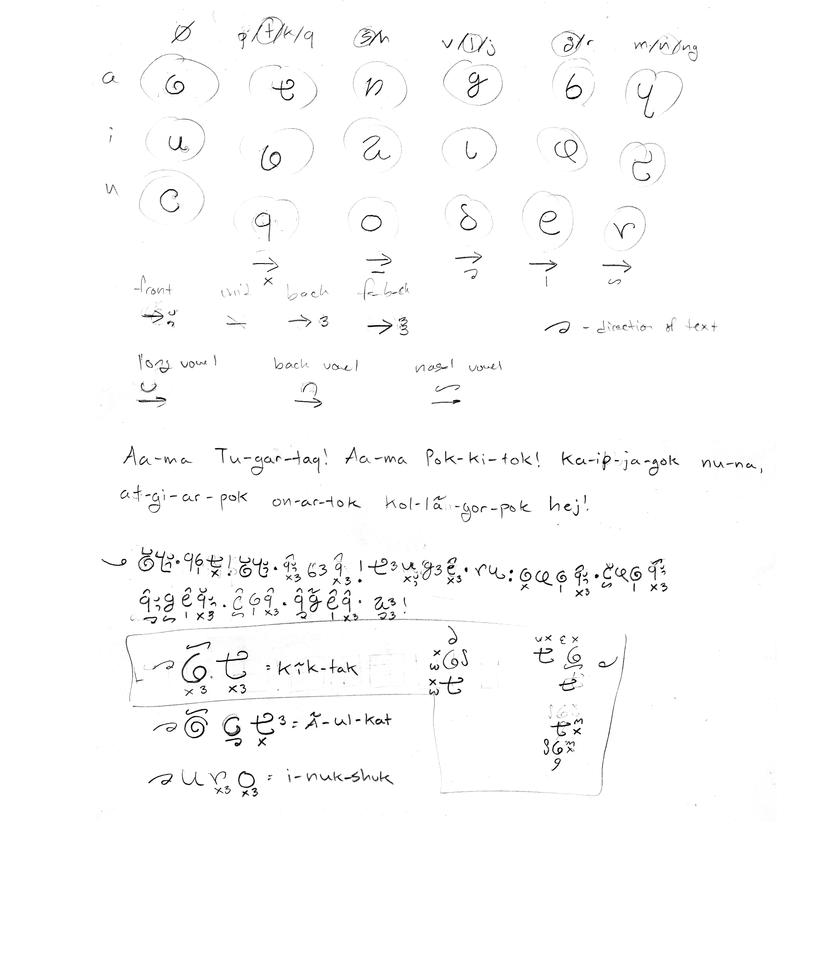

Interesting stuff about the development of the alphabet, sounds like Chief Sequoya apprenticed himself to Saints Cyril and Methodius and went on to invent hiragana. Mind if I take a stab at designing some of those letters?

Sure thing, go right ahead.

Essentially, its what you get when a relatively gifted polymath gets his hands on a good idea - basically, equal parts borrowing from all over the place, genuine inspirations, and awkward kluges. Rendered literally, translations of early writing would read something like "Me am Grandfather, am me happy write to you." Grandfather kept tinkering with it, fine tuning it for much of his life.

And of course, within Thule society, particularly among the Shamans, there's no formal stamp or seal of approval for Grandfather's form of script, so a lot of gifted men and women all over the place, having seen the idea prove out, start tinkering with their own variations, or reinventing from scratch.... the same way that turn of the 20th century inventors were building all sorts of designs for cars, or the same way that late 20th century inventors were building all sorts of computers and software packages.

That heterodoxy is a strong feature of Thule society, at least in this phase. Someone comes up with a good idea, and it will spread fast. And while its spreading, everyone and their uncle will start screwing with it to try and get a little advantage or improvement.

In terms of the invention and wildfire spread of Thule writing, I'm drawing on the comparatively recent OTL historical examples of writing transmission.

The clearest case is the Cherokee Syllabary, invented by an illiterate Cherokee silversmith named Sequoyah (also named George Gist). He had regular contact with whites and was impressed with their written language. He decided to create his own, between 1809 and 1821. He was quite obsessed with the task, faced accusations of witchcraft and at points even quit farming to work on it. He went up a huge blind alley, trying to come up with a symbol for every Cherokee word, but eventually had a breakthrough when he crafted a syllabary. Within a decade, the Cherokee syllabary was read and written through much of the Cherokee nation, with a literacy rate as high or higher than the white community.

The Cherokee Syllabary appears to have directly inspired the Vai Syallabary which came into use among the Vai tribe in 1830, developed by Momulu Duwalu Bukele.

The example of the Cherokee syllabary appeared to have been a trigger or an inspiration for a northern missionary in what is now the Canadian province of Manitoba to develop Cree syllabics in 1840. This writing system, spread like wildfire and came rapidly into use even among Cree who had not had contact with Europeans.

A peculiar case is MicMac hieroglyphs. It's not entirely clear. MicMac glyphs seem to have preceded the arrival of the Europeans and were used commonly. The argument has been that this may be an indigenous writing system, or that the glyphs were merely memory or recall aids, which missionairies later adapted into a writing system. Even if we accept the second hypothesis, it seems that the MicMac may have been closely approaching indigenous writing.

Another interesting case is the Rongo Rongo 'written language' of the Rapa Nui (Easter Island). This seems to be quite controversial. There are very few remnants of it left, there is no one who can read it. There is debate over whether the Rongo Rongo actually constitutes a written language. And there's debate over whether, if it is a written language, the Rongo Rongo is an indigenously developed written language or was inspired by contact with Europeans. If in fact, it was inspired by contact with Europeans, this is another case of wild fire proliferation - the mere example and explanation causing a written language to literally burst upon the scene and be widely adopted.

There are doubtless a number of other cases, but these are all particularly interesting in their own way.

One curious thing is that from what we can determine 'original' written languages - ie, developed autonomously without being inspired elsewhere, seem to start off as counting and accounting systems. Means of keeping track of who has what, who is owed what, who owes what. Only as the counting develops does the proto-script assume more and more functions and baggage. So far as we can tell, there's a long evolutionary process for a written language to develop.

For this reason, so far as we can tell, there are only a handful of instances of the genuine invention of written languages. It occurs often enough and in widely scattered enough locations to suggest that it may be a fairly inevitable development. But it's not that common.

A lot more written languages seem to be inspired. They may be dramatically different from the inspirations. But there seems to have been some kind of cultural contact, some people in the receiving culture seem to grasp the utilitly and use of written language, and they take that idea and develop their own - sometimes similar, sometimes radically different.

It doesn't automatically happen all the time. The Maya for instance developed a written language, but we don't see their neighbors racing to pick it up.

Of course, most such original developments and inspirations are for the most part ancient history. We can track back to and guess at the original writing systems, and make a fair case as to the ones which were derived through inspiration, but that tells us little about the manner in which they were developed, or the speed of development and proliferation.

For that, I have to turn to the examples of the 19th century aboriginal written languages of North America, Africa and Polynesia. From the examples, I find myself drawing two conclusions:

1) Inspired languages are not a case of reinventing the wheel, they're reinventing the SUV. An inspired written language seems to bypass all the conceptual development that accompanies original developments of written languages. They don't develop first as accounting or counting systems and go through stages of development. Rather, they seem to arrive 'state of the art' - ie, the people who have learned of the idea of having a written language have also acquired the ideas of all the bells and whistles, functions and capacities of a written language, and when they do their own, they build all that in from the start. In a sense, rather than learning to crawl or walk first, an inspired written language often starts out running.

2) Inspired languages will spread like wildfire. They seem to get adopted extremely rapidly. Cree syllabics outpaced European contact. The Cherokee system surpassed white literacy rates in less than a decade. The Rongo Rongo may have come from glancing contact with occasional ships.

Now, there's one objection to the modern inspired written languages. At least in terms of Cree, Ojibwa and Cherokee syllabics. All of these groups were in regular contact with Europeans for a century or more before they broke through to a written language. In a sense, they were Europeanized. So its not like someone got off the boat and a year later the Cree were writing letters to each other. There were long periods of cultural contact during which writing did not transmit, but which may have prepared these cultures for writing.

But then again, this may be exactly the case with the Rongo Rongo, or the MicMac Hieroglyphs, or the Vai syllabary. Hard to tell. At the very least, the Rongo Rongo is the most troubling case, although there is so little hard evidence. One theory for the Rongorongo is that it was inspired by a 1770 Spanish expedition and the signing of a treaty. If that is the case, then the point of inspiration here was incredibly brief contact.

And of course, as I've pointed out, no other meso-american group seems to have been inspired by the Mayan script.

The conclusion I tend to draw is that the emergence of inspired scripts seems to be an unpredictable bolt of lightning. Someone gets the idea and goes ahead and does it. But that someone may show up early or late. Statistically, they'll show up eventually. But there's no clear telling when.

A peculiarity is that the Cree and Ojibwa syllabits were used by non-Agricultural hunter gatherers. I think this may also hold true of the Micmacs. Of all peoples, you'd expect that hunter gatherers would have had the least need. The fact that they adopted it so readily seems to suggest that once the idea is there and there's a vehicle, its valuable enough to be adopted readily.

In the case of the Thule, it should be noted that by the time of the Norse Interchange, they've become a fairly sophisticated agricultural and herding civilization with a fair degree of complexity. Given the social complexity that they are dealing with, I think that there's a lot stronger incentive and motivation, a lot more need for a workable script, than you would find in hunter gatherers. So, their invention and adoption of a written language is likely to be a lot faster and earlier, they're more prone to an early bolt of lightning and wildfire spread. There's more applications or niches in their society, more opportunities for writing to be useful, and for the utilitly of it to be more obvious, self evident and inspirational.

I don't really have anything too solid to back that up, except perhaps for the lightninglike rapid invention/adoption of the RongoRongo after a single brief Spanish contact. The Rapa Nui culture was extremely complicated, extremely advanced in terms of monument building and so forth.

We don't have anything on how difficult it is to create such a thing. Sequoyah of the Cherokee diddled with it for a decade. But then again, he spent a long time going down a serious blind alley, and faced a lot of resistance. At one point one of his wives burned his work because she thought it was black magic, forcing him to start over from the beginning.

I would argue that it's reasonable, assuming no blind alleys, if someone stumbles onto a viable path at the outset, they can develop something useful in a year or two.

In the situation of Grandfather:

1) he's given inadvertently given a heavy duty crash course in the merit and use of a written language,

2) given two very different examples of written languages to draw from,

3) has a store of existing Thule symbols and glyphs to begin referring to,

4) is coming from a sophisticated and innovating culture,

5) is himself a member of a caste or tradition at the forefront of exploration and innovation and sophistication,

6) is a very smart guy himself (not a genius - but very smart),

7) he's gone to the Norse with the intention of making a name for himself and learning or obtaining things that might be useful, so he's on the make,

8) his culture has lots of 'plug ins' points and situations where a written language would be very useful.

Based on all of that, and from what I can glean from the 19th century inspired languages, and from what we can tell of prior language development, I think I can make an arguable case that its plausible that Grandfather could and would develop a written Thule script within a few years of meeting with, living with, working and trading with the Norse.

Anyone wants to, they can feel free to disagree and pose a counter-argument. But as far as I'm concerned, its a done deal. It's in the timeline now, and I'm not amending or taking it out.