The Invasion of Siberia

The Thule who came to Siberia did not find an empty land. Rather, the new territories they found were occupied by peoples who were in many ways as effective and competent as they were themselves.

The first peoples they encountered were the Chukchi, themselves an arctic people. It’s believed that a small group of Chukchi crossed into North America approximately 13,000 years ago, and became the ancestors of most of the American native population. They and their language are considered to be unrelated to the Thule.

Like the Thule, the Chukchi had domesticated and used the sled dog, and they had had it for a long time. The Siberian Husky of the Chukchi and the Alaskan Malemute of the Thule are extremely closely related, and while the Chuckchi and Thule peoples were unrelated, the dogs had a common ancestor. Given that the Thule left Asia three thousand years ago, that means that the Chukchi or their ancestors probably had sled dogs for at least that long or longer. The Chukchi were experienced seal hunters and dog sledders for thousands of years, a match for the Thule in this regard.

The Chuckchi were also accomplished reindeer hunters, and may have had domesticated or semi-domesticated reindeer as early as the time of contact. Reindeer domestication or semi-domestication in different areas ranged as far back as 3000 years ago, to as recently as 500 years ago.

Further, the Chukchi made far more use of plants and plant harvest than the Thule of OTL. As a side note, almost all of the edible arctic plants I’ve described were harvested regularly and skillfully by the Chukchi.

In our timeline, the Russian Empire invaded almost continuously, from 1701 to 1762, attempting to conquer, overwhelm, and eventually extirpate the Chukchi and their cousins the Koryak. Notwithstanding that this was the largest European Empire, armed with firearms, cannon, and a thousand years of martial tradition, they failed, kept on failing and eventually gave up. The Chukchi are rumoured to have kept the head of one particularly ruthless Russian general as a war trophy. They were nobody’s pushover.

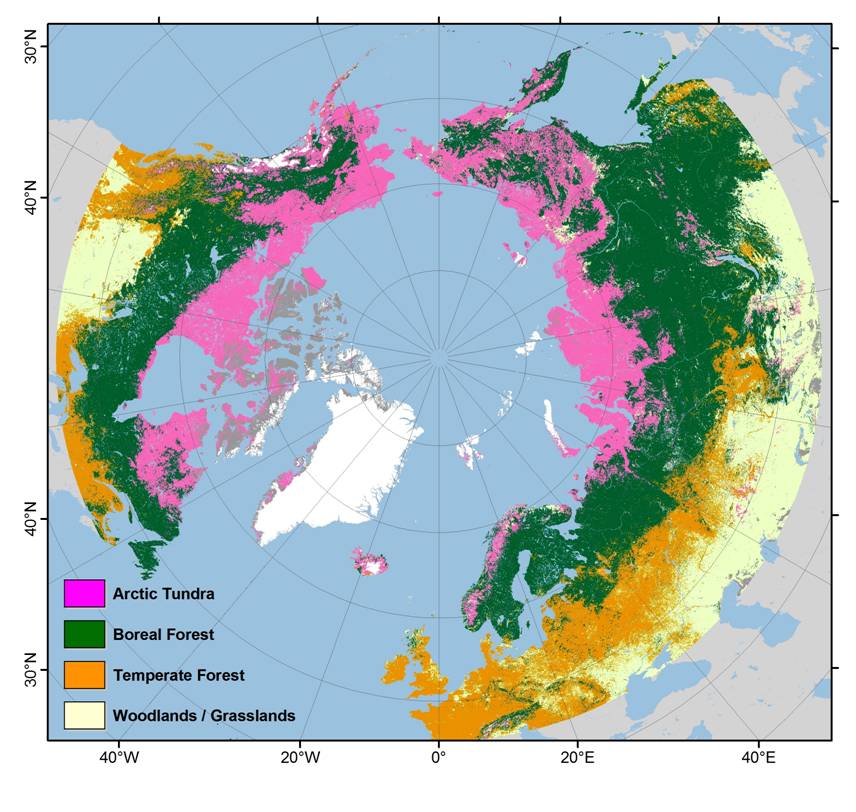

The Chukchi were an essentially neolithic society confronting a far more technologically advanced culture. How did they win against Russia? They made better use of mobility and climate. Their environment was largely arctic and subarctic tundra, unsuitable for horses. The Chukchi avoided direct battle and confrontation, using their dogsleds to outpace and run around the Russians. Their preference was to wait till the Russians had camped, sneak close, and pepper them with arrows before withdrawing. The russian fondness for camps and supply trains made effective targets.

Another favoured tactic was to lure them into rocky country which offered extensive secure cover. Russian firearms had far better range than bow and arrow, but that advantage only existed when there were clear lines. With short range cover, the Chukchi could reach the Russians with bows and arrows. Bows and arrows in the harsh winter conditions offered advantages to firearms, which were often unreliable.

Economic decisions played a part as well. The Chukchi had little of value to the Russians. They were not major fur producers. Most of the Fur harvest took place further south in the Steppe. After seventy years of major expenditure, the Russians simply added up the numbers and decided it wasn’t worth it. They then shifted to trading posts, and this became the effective means of political and economic domination. There’s more than one way to skin a cat.

Now the struggle between the Chukchi and the Russians is hardly indicative of how the Thule would fare against the Chukchi. But its pretty clear that they were a hardy, warlike people with mastery of their environment and an arctic package as or more sophisticated than the OTL Thule. In short, the Chukchi were going to be tough customers.

South of the Chukchi, occupying the north half of the Kamchatka peninsula, and the adjacent portions of the Siberian mainland were the Koryak, a closely related people. As capable and as warlike as the Chukchi, they’d also kicked Russian ass. They tended to divide into two groups, the village Koryuk, who made their living fishing and hunting seal along the coast, and the inland Koryuk who subsisted on hunting or herding caribou.

The Koryuk language and mythology seem closely related to those of the Indians of the British Colombia and Alaskan panhandle. As much as 80% of their myths and folktales seem to overlap.

And to the south of that, on Kamchatka, were the Itelman, another relative of the Chukchi and Koryak, another arctic or sub-arctic people. As we moved south, population density increased, and with proximity came warfare When the Russians began exploring the region in our timeline, they found the Itelman living in fortified villages, making regular war upon their neighbors. They ingratiated themselves by using their weapons to destroy some groups of Itelmen for other groups of Itelmen.

The Itelmens to the south didn’t do nearly as well against the Russians, despite greater population and a more settled population. Part of the problem, I think, was that they were a much more settled people, living in stable communities. The Chukchi were regional nomads so it amounted to very little effort to pull up stakes and lead the Russians on a chase. The Itelmen were not nearly so mobile. As well, the Itelmen were probably relatively wealthier. They inhabited a warmer region, produced more valuable furs, etc. More incentive to overrun them.

Although more advanced than the Chukchi in terms of being comparatively wealthier, more populous and living in fortified communities, they were more generally accessible by sea, they were neolithic, they were non-agricultural, and they weren’t politically organized. Living in communities made them a bigger and easier target, and there was much more pay off.

East of the Chukchi and Koryak, in the far north, were the Yakut, a widespread and very successful peoples. The Yakut practiced a variety of lifestyles. Inland, where summer temperatures were moderate, and trees and grassland endured, they herded cattle, raised horses and practiced horticulture.

As they moved north to the arctic coasts, they abandoned most of their domesticates, shifting to a lifestyle based around reindeer herding and fishing.

Prior to the Yakut, the Evens, Evenk and Yukaghir had occupied the arctic coastlines, and these peoples still persisted in many areas.

This is barely more than a snapshot of what the Thule faced as they made their way across the Bering strait into Siberia.

In OTL, the Thule did succeed in crossing and establishing themselves along the siberian coasts of the Chukchi peninsula. So, there must have been some advantages to the Thule toolkit that allowed them to compete and find a niche.

But they never succeeded in displacing the Chukchi as they did the Dorset, or even pushing far into Chukchi territories. Certainly they never confronted the Koryak, the Italmen, the Yakut, Even and Evenks or others. The peoples they met, on the whole, were a match or more than a match for them, had equivalent or superior packages, more varied diets, more plants, and perhaps even domesticated reindeer in addition to dogs.

My impression was that the Siberian Thule who became the Yupik survived because they managed to occupy the most marginal coastal lands where even the Chukchi had difficulty. Thule likely had been able to find a place for themselves at the edges, in lands and shores too barren for their neighbors, and eke out a precarious existence, using their ability to survive and prosper where no one else could.

It’s also likely that the Thule migration to Siberia came in relatively small numbers, which made it difficult for them to push the Chukchi, who had the population advantage. The upside of that might have been that relatively small numbers put less pressure on the land and tended not to bring them into conflict with the Chukchi.

Initially, it occurs in OTL, with the proto-Yupik, hunter/gatherers establishing themselves along the coasts of the Chukchi peninsula in areas too marginal for the Chukchi.

But there’s more of them in this ATL. And they come in further waves, staying with their relatives and then moving on, looking for lands that they can survive in, lands that they do not have to contest.

So they move a lot further along the coasts, along the Arctic and Pacific. There’s also more friction with the Chukchi. Their consumption of plants gives them a little bit of an advantage over their OTL counterparts. But these are extremely marginal areas, so there’s not a lot of Sweetvetch or Claytonia overall. There's probably a tendency to a plant free diet, initially, and perhaps a tendency to import or invent the same pre-agricultural practices that we see in the east.

Where they start to diverge is when subsequent groups of Thule start coming in, bringing with them copper and bronze tools and weapons, and the pre-agricultural and components of agricultural practice.

There is more conflict with the Chukchi, but increasingly, the Thule have an edge in terms of land use. Ptarmigan and microclimate engineering allows them a stronger food base for their population.

There will be head to head competition in that both Chuchki and Thule have sled dogs and caribou as herd animals. I don’t know if the Chuchki ride caribou, I think that there may be some evidence of that. But if they do, the Thule will pick it up fast. Overall, the Thule may make more efficient use of Caribou as pack and draft animals.

But the real game changer will be Musk Ox, which will give the Thule clear production advantage in the most marginal areas. Tolerant to conditions that even reindeer or caribou have trouble with, they have no counterparts in Siberia. There are no Siberian Musk Ox. They’re a competitive edge in the most marginal regions, allowing the Thule to prosper where the Chuckchi are weak. And where the Thule can establish a beach head and prosper, they can eventually push.

That and microclimate agriculture which follows, as it comes together fully, will see the Thule’s less productive territory becoming more productive than the Chuchki. From there, the Chuchki get slowly pushed back.

It will not be easy, the Chuchki are ferocious enough to kick Russian ass. They’ll probably hang onto at least some of their territory, and may displace internal groups.

But this timeline, the Thule were coming in greater numbers, more closely integrated with their home society and thus able to draw on allies in Alaska. They came with an improved or improving hunting package that extended to toggle harpoons, fish traps and fish nets acquired from the east and south.

They came with copper and bronze. They came with a potent suite of domesticates that extended beyond dogs and reindeer, but included musk ox, ptarmigan, hare and even semi-domesticates.

And they came with a set of pre-agricultural and agricultural practices that allowed them to make formerly barren lands produce, to increase harvests beyond those of their neighbors and to extend harvests beyond the ranges where they’d previously been possible.

The Thule, travelling along the Arctic ocean coasts will eventually move past the Chukchi, or bypass them, and encounter the Yakut. They push the Yakut inland, relying on their cultural and technological superior package. But probably when they get to the steppe and grasslands, that will be their limit. The Yakut package at that point beats the Thule package.

Kamchatka is going to be a battle zone as the Chuchki, retreat and merge with the Koryuk who merge with the Italmen. You might see some caste evolution going on, as the Chuchki and Koryuk conquer the more numerous Italmen, and set themselves up as a warrior or noble class.

Alternately, they may just pile up in layers, with Chuchki pushing Koryuk south, the Koryuk pushing the Italmen south.

The further south, the more alien the landscape is going to be for the Thule. Musk Ox will fare poorly. Pycrete storage will become unreliable. The more effective the defenders are going to be. And some likelihood that they may even acquire or reproduce the Thule agricultural package.